Abstract

Despite many years of study, questions remain about why patients do or do not take medicines and what can be done to change their behaviour. Hypertension is poorly controlled in the UK and poor compliance is one possible reason for this. Recent questionnaires based on the self-regulatory model have been successfully used to assess illness perceptions and beliefs about medicines. This study was designed to describe hypertensive patients’ beliefs about their illness and medication using the self-regulatory model and investigate whether these beliefs influence compliance with antihypertensive medication. We recruited 514 patients from our secondary care population. These patients were asked to complete a questionnaire that included the Beliefs about Medicines and Illness Perception Questionnaires. A case note review was also undertaken. Analysis shows that patients who believe in the necessity of medication are more likely to be compliant (odds ratio (OR)) 3.06 (95% CI 1.74-5.38), P<0.001). Other important predictive factors in this population are age (OR 4.82 (2.85-8.15), P<0.001), emotional response to illness (OR 0.65 (0.47-0.90), P=0.01) and belief in personal ability to control illness (OR 0.59 (0.40-0.89), P=0.01). Beliefs about illness and about medicines are interconnected; aspects that are not directly related to compliance influence it indirectly. The self-regulatory model is useful in assessing patients health beliefs. Beliefs about specific medications and about hypertension are predictive of compliance. Information about health beliefs is important in achieving concordance and may be a target for intervention to improve compliance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although many advances in treatment have been made, success in blood pressure (BP) control in real-life practice has been limited, with poor rates of population BP control in the UK and other parts of the world.1 Control of hypertension is paramount in efforts towards primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Poor compliance with antihypertensive medication is one possible reason why success in clinical trials has not been translated into everyday practice.

Despite many years of study, questions remain about why patients do or do not take medicines and what can be done to change their behaviour. Recently, the concept of concordance has revolutionised the way in which doctors and patients interact over medications, highlighting the importance of patients’ ideas.

Rates of noncompliance may be as high as 50% in chronic conditions.2 Studies in hypertension vary markedly in estimates of compliance; levels as different as 20 and 80% are quoted.3 Patients who are not taking their medication as prescribed may be doing so intentionally or unintentionally. Many patients who are partially or poorly compliant are making rational choices over their medication. This is a point worthy of consideration given that doctors generally regard poor compliance as the consequence of forgetfulness, carelessness or ambivalence on the part of the patient rather than as a definite decision.

Many factors that may influence patients’ decisions over compliance have been studied previously. Reasons for adherence to treatment include faith in the physician, fear of the complications of hypertension and desire to control BP. Nonadherence has been associated with misunderstanding of the condition, perceived improvement in health, worsening in health, general disapproval of medications and concern over side effects.2, 4 Many of the instances of patients not taking medicines to minimise side effects are pragmatic.3 For the majority of patients who have no symptoms with hypertension, the fact that they do not feel unwell may encourage noncompliance. Side effects may be unacceptable in a condition that is asymptomatic. The number of medicines prescribed may also influence compliance, with a reduction in compliance as the regime becomes more complex.5 These factors alone do not provide a full explanation of patients’ decisions and behaviour. In order to do this, health beliefs in compliance have also been studied.

Many psychological theories have been used to examine health beliefs in the context of compliance. The health belief model6 and theory of planned behaviour7 have been the most frequently used, providing some helpful information. The health belief model proposes that patients weigh up a health-related behaviour (eg compliance) by considering their perceived susceptibility to an illness and the seriousness of the illness, as well as the benefits of the action. The model includes the concept of barriers to action and cues which might prompt it. The theory of planned behaviour, on the other hand, describes action as secondary to intention. In turn, intention is derived from attitude, perceived control over the behaviour and the views of others (subjective norm). The self-regulatory model8 is proving a useful model in assessing specific health beliefs and how they influence medication-taking behaviour.9, 10, 11, 12

The self-regulatory model proposes that health-related behaviour is strongly influenced by ideas around certain themes (termed illness representations). There are five themes: identity, time-line, cause, consequences and cure/control. Beliefs about these components of illness determine coping strategies. Compliance is regarded as a specific problem focused coping strategy; patients weigh up whether the proposed treatment is in line with what they believe about their illness in order to decide whether or not to comply with it. Patients will also assess the success of their treatment and may not continue with it if they perceive it to be unsuccessful. Many studies have considered one or two aspects of the model, but few have examined the whole picture. The production of a new questionnaire allows for a more complete assessment. Since the publication of the Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R),13 a number of studies have utilised it to look at a range of diseases. Horne and Weinman have proposed that beliefs about treatment are also important and can be added into this model.10 They suggest that beliefs about actual therapy will also influence whether it is taken.

Initial data collected by Horne's group show the complex way in which patients may think about their medicines. Most patients thought that their medicines were necessary, but a significant proportion of these also had serious concerns about taking them and therefore held the two ideas in tension. The authors then went on to examine whether there is a correlation between the Beliefs about Medicines questionnaire (BMQ) and a measure of adherence. They report statistically significant relationships between high specific-necessity scores and good compliance and high specific-concern scores and poor compliance.14

Identity, consequence and specific-necessity were found to relate to compliance in a cohort of haemophiliacs.15 Again, consequence beliefs were found to predict compliance in a study of patients with hypercholesterolaemia.16 A recent meta-analysis that looked at studies using the self-regulatory model, but not necessarily the IPQ, showed a correlation between specific problem focused coping strategies (including attendance at appointments and compliance) and perceived controllability.14

Although the number of studies that have used the self-regulatory model through the IPQ (and IPQ-R) and BMQ, findings are likely to be different in different illnesses13 and only some studies have considered compliance or patient outcomes.

Our study aims to describe patients’ beliefs about their illness and medication using the self-regulatory model, and investigate whether these beliefs influence compliance.

Methods

Patients were recruited from a secondary care hypertension clinic and shared care scheme. At present, there are over 7000 patients registered in this system. Patients attending the hypertension clinic on consecutive weeks between October 2001 and January 2002 were approached opportunistically and asked to participate. Those patients who did not attend for their clinic appointment were sent an invitation to participate by mail.

Patients in the shared care scheme were sent information about the study along with their regular shared care documents. Patients were taken consecutively from the mailing list for the months in question. Questionnaires were sent in November 2001, April 2002 and May 2002. One reminder was sent at approximately 4–6 weeks.

Our questionnaire included demographic information, the BMQ, the IPQ-R and questions to assess knowledge about hypertension and perception of risk. Compliance was measured by Morisky's self-report questionnaire.17 This consists of four questions about medication taking, which cover forgetfulness, carelessness and stopping medication due to improvement or deterioration in symptoms. Patients are then divided into high-, medium- and low-compliance categories on the basis of the number of positive answers. Owing to the small numbers of patients with very low compliance, patients who had high compliance were classified as compliant and those in Morisky's medium and low categories were amalgamated and classified as poorly compliant in order to allow for statistical analysis. This method was used successfully by Patel.18

A secondary care case note review was performed to assess BP control and past medical history. BP was measured at the clinic visit where patients completed the questionnaire. For those patients who received their questionnaire in the post, BP was taken by their GP when they attended for review prompted by the shared care reminder.

The IPQ-R13 was used. It measures the identity, time, cause, consequence and control/cure beliefs from the self-regulatory model, but also includes a measure of emotional response and divides control beliefs into personal attempts to control illness and control of illness by treatment. The questionnaire is designed to be adapted for use in different illnesses, and some elements may not be applicable to some specific illnesses. For example, the identity/symptoms element is not directly applicable to an asymptomatic condition like hypertension. The BMQ10 examines beliefs about specific medicines and about medicines in general.

The IPQ-R has 22 questions that are used to examine time, consequence and control beliefs as well as emotional response. A further list of possible causes is given for patients to agree or disagree with. Five-point Likert scales are used in all questions and the score for each theme is taken as the mean of the questions relevant to that theme as described by the authors. Higher scores indicate a strong emotional response, perception that the illness is chronic, that is cyclic in pattern, that it has serious consequences, and that control or cure is possible. Similarly, the BMQ has 18 questions using five-point Likert scales. The first 10 evaluate attitudes about the necessity of, and the level of concern about, the current medication that the patient is taking. The next eight questions are about general attitudes to medicines. Scores are taken from the sum of answers to all relevant questions. High scores signify agreement with the concept of necessity, high levels of concern and agreement with the idea that medicines are harmful or overused.

Illness perception scales and beliefs about medication scales were analysed using Cronbach's alpha to ensure reliability. The IPQ-R control scale was found to have a low alpha score suggesting that the scale was not assessing one consistent idea. The control scale asks about control and cure, which are thought to be separate concepts in this population, and were therefore analysed separately.

Data were collected in a Microsoft Access database and analysed using the SPSS v10.1. Statistical analysis was performed using t-tests and Pearson's correlations for continuous variables and χ2-tests for noncontinuous variables. Patients were divided into older (⩾60) and younger age (<60) groups for ease of analysis (when treated as a continuous variable similar relationships were seen). The age that was chosen was 60 years because this is a cutoff for retirement and for entitlement to free prescriptions. Educational atttainment was assessed by asking patients to say whether they had gained national qualifications at secondary school (‘o’ grades, ‘higher grades’ or ‘school leaving certificate’), a university degree or post graduate qualification. Patients were then classified as ‘none’ (no formal qualifications), ‘secondary’ (secondary school level qualifications) or ‘university’ (university degree or post graduate qualification). Scores from the BMQ were divided into high and low as per the original paper.10 Multiple logistic regression was then used to identify the most important predictive variables for compliance and health beliefs, using the variables that were identified as important in univariate analysis.

Ethics committee approval for the project was obtained from the Grampian Regional Ethics Committee. Informed consent was given by all participants.

Results

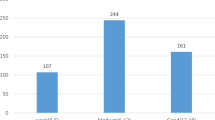

Questionnaires were completed by 272 patients at the hypertension clinic (65% of attendees). Of the 450 patients from the shared care scheme who were sent questionnaires, 242 were returned completed (54%). There were no significant difference in age or gender between responders and nonresponders. Complete data were not available for all patients. This was mainly due the fact that some patients were not on medication currently. They did not complete the self-reported compliance questions and those regarding current medication.

The mean age of patient was 60 years. There were 247 (48%) female patients and 267 (52%) male patients. Compliance was high with only 112 (22%) patients in the poor compliance category. Full patient characteristics are listed in Table 1.

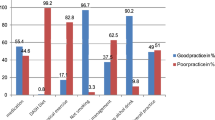

In general, patients perceived medications to be necessary, but a substantial proportion had concerns about their medicines (see Table 2). Scores indicating strong perception of chronicity were seen, but also perceptions that BP is variable over time. Emotional response was generally low, although some patients scored very high on this scale. The score for consequence was not particularly high, but both treatment and personal control were high. The most important causes were psychological and risk factors in patients’ perceptions. Means for all illness representations are shown in Table 3.

Diastolic, but not systolic, BP control was associated with good compliance. The mean diastolic BP in the good compliance group was 85 mmHg and 91 mmHg in the poor compliance group (mean difference 6 mmHg (95% CI 3.5-8.2), P<0.001). This remained significant after age was controlled for.

Compliance was significantly influenced by age and gender. Older patients are more likely to be compliant than younger patients (odds ratio (OR)) 5.9, P<0.001). Women are more likely to be compliant according to self-report than men (OR 0.6, P=0.015). Other demographic variables such as level of education were not associated with compliance.

The specific elements of the BMQ were associated with compliance. Patients who had high specific-necessity scores were more likely to be compliant (OR 3.2, P<0.001). Similarly, patients who had high-specific-concern scores were less likely to be compliant (OR 0.6, P=0.028). There were no significant relationships between the general-harm and general-overuse beliefs and compliance.

Aspects of illness perception were found to be associated with compliance. Higher emotional response to illness was related to poorer compliance (mean difference 0.23 (0.07–0.38), P=0.004). Patients who had lower consequence perceptions had higher compliance (mean difference 0.18 (0.05–0.31), P=0.009). Lower personal control beliefs were associated with higher compliance (mean difference 0.28 (0.14–0.42), P<0.001), whereas high-treatment control beliefs were associated with high compliance (mean difference 0.16 (0.03–0.28), P=0.015). When a distinction was made between control and cure in treatment beliefs, compliance was found to be associated with a strong belief in the ability of treatment to cure hypertension rather than control it (mean difference 0.27 (0.08–0.47), P=0.006).

Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that age, specific-necessity, emotional response to illness and personal control perception were most predictive of compliance in this population (see Table 4).

Analysis of the factors that were associated with the individual items in the BMQ and IPQ scales was performed. Age has a significant influence on beliefs about medications in this population. In particular, specific-necessity is related to age, with older patients having higher scores than younger patients (OR 2.0, P=0.004). Younger patients were more likely to have high specific-concern scores (OR 0.5, P=0.002). There were no relationships between general-harm or general-overuse and age. Older patients had lower emotional response (mean difference 0.16 (0.03-0.29), P=0.015), consequence (mean difference 0.15 (0.44–0.27), P=0.006) and personal control beliefs (mean difference 0.35 (0.24–0.46), P<0.001), but higher treatment cure beliefs (mean difference 0.32 (0.16–0.48), P<0.001) than younger patients (see Table 5).

None of the BMQ components were related to gender. Men were more likely to believe that hypertension had serious consequences than women (mean difference 0.16 (0.05–0.27), P=0.05). Men were also significantly more likely to believe in the possibility of personal control of blood pressure (mean difference 0.27 (0.16–0.39), P<0.001), but there was no gender difference in belief that treatment can control illness.

There was no gender difference in thinking that the cause of high BP is psychological, immunological or due to chance. Men were more likely than women to believe that risk factors caused hypertension (mean difference 0.23 (0.12–0.35), P<0.001).

Beliefs about medicine were affected by educational level. Patients in the lowest education category were more likely to believe that medicines were necessary (χ2=7.154, P=0.028). Patients in the secondary and university education groups were similar to each other. Educational level did not affect specific-concern, or general-harm. General-overuse scores were higher in patients with more education (χ2=4.732, P=0.094). Education was not a significant predictor of medication beliefs in multiple regression analysis.

The number of medications was not associated with compliance.

Specific-necessity belief was best predicted using a model comprising age, number of medicines, perceptions of time, consequence and cure (see Table 6). Increasing age, number of medicines and stronger beliefs in the chronicity, consequences and likelihood of cure were associated with higher necessity beliefs.

Specific-concern belief was best predicted by a model comprising general-harm, general-overuse, emotional response, perception of consequence and age (see Table 7).

Discussion

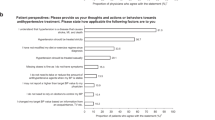

Our study suggests that patients with hypertension think that their medicines are necessary. Although they have concerns about taking medicines, these are mainly outweighed by a belief in the necessity of the medication. Illness representations suggest that patients believe hypertension is a long-term condition and that it can be controlled, but surprisingly beliefs in serious consequences and emotional response are low. Patients think the cause of hypertension is psychological or related to risk factors such as smoking and obesity. Good compliance is associated with a number of health beliefs as measured by the self-regulatory model, particularly specific-necessity, personal control and emotional response. The demographic factors, such as age, which are associated with compliance in our study, may be mediated through these beliefs. Compliance was also related to blood pressure and thus it is possible that health beliefs that are related to compliance may be associated with clinical outcomes. This could be a focus for further study.

Belief in the necessity of medication is high in this patient population and is strongly related to compliance. It is logical that this should be the case. Horne suggests that necessity beliefs are likely to be strong in patients with chronic illness, and may be more influential in acute conditions.10 Although this may be so, necessity is probably important in an asymptomatic condition such as hypertension.

Patients with strong concerns are less likely to be compliant with medication, although this effect does not remain significant when age, necessity and aspects of the illness perception questionnaire are taken into account. In many patients, there are high scores for both necessity and concern; the most powerful perception of the two seems to determine compliance. General beliefs about medication indirectly influence compliance via specific concern as proposed by original authors’ model.19 Overall, our findings are in line with those found by Horne.10, 19

Although one might speculate that a concept of chronicity is essential for the continuation of medication taking, time line was not related to compliance in this population. Similarly the concept that illness is cyclical might be expected to relate to poorer compliance, with intervals where patients perceive BP to be good being associated with less need to take medication. The lack of relationship might be due to the fact that these are not newly diagnosed patients. Some studies have found that illnesses that are perceived to be shorter were also perceived to be more controllable.16 We did not find this relationship.

Perception of consequence was inversely related to compliance. This finding is counter-intuitive, however, consequence may elicit an emotional response (we found a significant relationship between the two) and maladaptive coping, which could explain poorer compliance. Consequence has certainly been shown to be associated with expressing emotions, denial/avoidance strategies and poor psychological well-being in other studies.16

Representations about the control and cure of illness have been noted to be important in previous studies.18 The authors of the IPQ-R found that patients differentiate between personal ability to control BP and the ability of treatment to do so and therefore separated out these two themes.13 Our patients also showed very different views about the two. Those who thought they could personally control their BP were less likely to be compliant, whereas those who thought their treatment would control BP were more likely to be compliant. This was further complicated by the finding that control and cure of BP were different ideas held by patients. Compliant patients thought that treatment would cure rather than just control BP (See also Table 8).

Poorer compliance with higher personal control beliefs may be a reflection of an internal locus of control. To patients with an external locus of control, accepting recommended treatment may be in line with their low self-confidence. A relationship between high self-efficacy and poor compliance has been documented in other studies.18, 20

Overall controllability is strongly associated with coping procedures in the literature.16 Illnesses that are thought to be controllable are associated with problem focussed coping (for example compliance), where as more maladaptive responses (such as denial/avoidance) are seen in illnesses that are perceived to be uncontrollable (as well as more symptomatic and chronic).

Emotional response to illness is related to poor compliance in this population. An emotional response may adversely affect compliance by encouraging maladaptive coping mechanisms (such as denial), or it may be that anxious or depressed patients are less compliant due to psychiatric illness.20, 21

Cause perceptions might be expected to be related to compliance. For instance, in a popular lay model of hypertension, psychological factors are thought to be the cause. Patients who have models that differ from medical models of hypertension have been shown to have poorer compliance and higher BPs.15 We did not find any signficant relationships between cause perceptions and compliance however.

We theorise that health beliefs not only predict compliance, but that these may be more consistent in doing so than demographic variables, which can vary widely between studies.22 We also propose that health beliefs mediate the relationship between demographic variables, such as age and gender, and compliance. This may explain the differences seen in studies of compliance, as age, gender and other demographic variables may lead patients to have different health beliefs in different populations. In our population, older patients and female patients were noticably more compliant. There may be influences on health beliefs which explain these findings.

Our study may have been limited by the method of estimating compliance. Reliably estimating compliance is challenging. This study did not have the resources to use electronic monitoring, which is regarded as the gold standard. It could be argued that self-reported compliance is not accurate enough to justify its use: however, the studies that have compared different types of measurement have found it to be a useful measure.23, 24 In fact, one author goes as far as to say that self-report should be included in all studies of compliance.23 It is certainly the most practical and inexpensive measure open to doctors in everyday practice. It could also be argued that patients’ thinking on their own medication-taking habits is important in a study of psychological factors.

The study population was a representative sample of the population served by our hypertension service. It may not reflect hypertensive patients who have never been referred to secondary care, however poor BP control and poor compliance are more likely to be present in a secondary care situation. Given the differences between studies of compliance, it is difficult to be sure how far our results can be generalised to other populations.

The self-regulatory model and in particular the beliefs about medicines and illness perception questionnaires are applicable to the study of compliance. Our findings support the relationships that have been theorised. More evidence to support the mediating role of health beliefs in compliance is needed, but our study has added to current knowledge in this area. Demographic variables are associated with beliefs as measured by the BMQ and IPQ-R in our study. It is not unreasonable to think that attitudes and beliefs may be different in different generations, with different levels of education or between men and women. The interaction between demographic variables, beliefs about illness and medicines and compliance is complex, and may differ between populations.

Exploring the health beliefs of patients may be important in achieving concordance. These questionnaires give researchers further ways of studying the psychological aspects of compliance and may be suitable for use in routine clinical practice. Further work is required to assess potential use in clinical practice and also to examine how and why patients form particular health beliefs. Health beliefs are also a possible target for interventions to improve compliance and thereby blood pressure. It may even be possible to make changes at a population level by changing the perceptions of illness and medication in society. This could in turn improve population BP control.

References

He FJ, MacGregor GA . Cost of poor blood pressure control in the UK: 62000 unnecessary deaths per year. J Hum Hyperten 2003; 17: 455–457.

Miller NH . Compliance with treatment regimens in chronic asymptomatic diseases. Am J Med 1997; 102: 43–49.

Dunbar-Jacob J, Mortimer-Stephens MK . Treatment adherence in chronic disease. J Clin Epidemiol 2001; 54: S57–S60.

Svensson S, Kjellgren KI, Ahlner J, Saljo R . Reasons for adherence with antihypertensive medication. Int J Cardiol 2000; 76: 157–163.

Iskedjian M et al. Relationship between daily dose frequency and adherence to antihypertensive pharmacotherapy: evidence from a meta-analysis. Clin Therap 2002; 24: 302–316.

Becker MH . The Health Belief Model and personal health behaviour. Health Educ Monogr 1974; 2 (4): 376–423.

Azjen I . From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behaviour. In: Kuhl J, Beckmann J (eds). Action control: From Cognition to Behaviour. Springer: Heidelberg, 1985, pp 11–39.

Leventhal H et al. Illness perceptions: theoretical foundations. In: Petrie KJ, Weinmann JA (eds). Perceptions of Health and Illness. Harwood: Amsterdam, 1997, pp 19–45.

Horne R, Weinman J . Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatments in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res 1999; 47: 555–567.

Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M . The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health 1999; 14: 1–24.

Hand CH, Adams M . How do attitudes to illness and treatment compare with self-reported behaviour in predicting inhaler use in asthma? Primary Care Respir J 2002; 11: 9–12.

Petrie KJ, Weinmann J, Sharpe N, Buckley J . Role of patients' view of their illness in predicting return to work and functioning after myocardial infarction: longitudinal study. B M J 1996; 312: 1191–1194.

Moss-Morris R et al. The Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R). Psychol Health 2002; 17: 1–16.

Llewellyn CD et al. The illness perceptions and treatment beliefs of individuals with severe haemophilia and their role in adherence to home treatment. Psychol Health 2003; 18: 185–200.

Brewer NT et al. Cholesterol control, medication adherence and illness cognition. Br J Health Psychol 2002; 7: 433–447.

Hagger MS, Orbell S . A meta-analytic review of the common-sense model of illness representations. Psychol Health 2003; 18: 141–184.

Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM . Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care 1986; 24: 67–74.

Patel RP, Taylor SD . Factors affecting medication adherence in hypertensive patients. Ann Pharmacother 2002; 36: 40–45.

Horne R . Representations of medication and treatment: Advances in theory and measurement. In: Petrie KJ, Weinmann JA (eds). Perceptions of Health and Illness. Harwood: Amsterdam, 1997, pp 155–188.

Wang PS et al. Noncompliance with antihypertensive medications: the impact of depressive symptoms and psychological factors. J Gen Intern Med 2002; 17: 504–511.

Wing RR, Phelan S, Tate D . The role of adherence in mediating the relationship between depression and health outcomes. J Psychosom Res 2002; 53: 877–881.

Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P, Denekens J . Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J Clin Pharmacy Therap 2001; 26: 331–342.

Choo PW et al. Validation of patient reports, automated pharmacy records and pill counts with electronic monitoring of adherence to antihypertensive therapy. Med Care 1999; 37: 846–857.

DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, Croghan TW . Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: a meta-analysis. Med Care 2002; 40: 794–811.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was provided by a small grant from Chest Heart and Stroke Scotland. Thanks to Graeme MacLennan, Statistician, HSRU, University of Aberdeen for assistance with statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ross, S., Walker, A. & MacLeod, M. Patient compliance in hypertension: role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs. J Hum Hypertens 18, 607–613 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1001721

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1001721

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

What are patients’ experiences of discontinuing clozapine and how does this impact their views on subsequent treatment?

BMC Psychiatry (2023)

-

The effect of health literacy intervention on adherence to medication of uncontrolled hypertensive patients using the M-health

BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making (2023)

-

A snapshot of patient experience of illness control after a hospital readmission in adults with chronic heart failure

BMC Nursing (2023)

-

A feasibility pilot trial of a peer-support educational behavioral intervention to improve diabetes medication adherence in African Americans

Pilot and Feasibility Studies (2022)

-

Psychometric evaluation of a culturally adapted illness perception questionnaire for African Americans with type 2 diabetes

BMC Public Health (2022)