Abstract

Background

This systematic appraisal was conducted to determine if the Evidence-Based Dentistry Journal (EBDJ) acts as a reliable and contemporary source of knowledge for practitioners across all disciplines within dentistry.

Objectives

The main objectives were to determine i) the year the articles were published and included in the EBDJ; ii) if the articles published covered all fields equally within dentistry; iii) the type of study design of the articles reported in the journal and; iv) the level of expertise of the writers of the commentaries.

Methods

This study used a systematic approach to assess the articles included in the journal. Data were extracted on the difference in the year the article was originally published and the year the article was included in the EBDJ, the number of articles in each dental discipline, the type of study designs included in the journal and the expertise of the commentators of each article. The information provided by the journal was validated by accessing the original articles through electronic databases.

Results

The appraisal considered the 582 articles that met the inclusion criteria. Overall, 45.3% of the articles were included in the EBDJ in the same year and 44.8% of the articles were included a year after they were originally published. The number of articles varied across disciplines within dentistry: 23.7% from dental public health, 18.4% from periodontology and 11.8% from orthodontics, with only 4.6% from prosthodontics, 1% from oral pathology and 0.5% from dental materials. Most of the articles were systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials at 72% and 22.3% respectively. The writers of the commentaries were mostly academics and hospital consultants (71.2% and 13.6% commentators).

Conclusions

On the whole, it can be concluded that the journal acts as a reliable and contemporary source of knowledge/evidence for dentists, however, not all specialities within dentistry had equal coverage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The term EBD is defined as ‘an approach to oral healthcare that requires the judicious integration of systematic assessments of clinically relevant scientific evidence, relating to the patient's oral and medical condition and history, with the dentist's clinical expertise and the patient's treatment needs and preferences.’1 The practice of EBD involves2:

-

Effective use of research evidence in clinical practice

-

Effective use of resources

-

Reliability on evidence rather than authority for clinical decision making

-

Development and monitoring of clinical performance.

However, the implementation of EBH and EBD has numerous barriers. One of the major barriers is the high volume of evidence. A study conducted in a hospital included 18 patients with 44 diagnoses for which there were 3679 pages of guidelines relevant to their immediate care. The reading time for these guidelines was estimated to be 122 hours.3 This highlighted the need to have a user's guide which provides explicit information based on high-quality evidence.4 In this, the evidence-based secondary journals were found to potentially serve the purpose of being a user's guide for evidence based practitioners. The EBMJ and the EBDJ are examples of such secondary journals. The EBDJ, a secondary journal, acts as a ‘filter and condenser’. It filters the articles depending on the quality of the articles and their clinical relevance and condenses them into easier abstracts to keep the readers up to date with latest advances in the field of dentistry.5 The articles in the journal help practitioners implement EBD through application of the findings of the articles. But whether these journals truly provide high quality reliable evidence is still questionable. A study by McKibbon and colleagues determined the number of high quality, clinically relevant articles published in secondary journals specific to internal medicine, general/family practice, general care nursing and mental health.6 However, there has been no such systematic appraisal of the EBDJ. The aim of this study was to determine whether the EBDJ acts as a reliable and contemporary source of knowledge, and provides evidence equally for practitioners across all disciplines within dentistry. The main objectives of the study were to:

-

Determine the year the articles were included and published in the EBDJ

-

Determine if the articles published in the EBDJ covered all fields equally within dentistry

-

Determine the type of study design of articles reported in the journal

-

Determine the level of expertise of the writers of the commentary.

Method

This study used a systematic approach to assess the articles included in the journal.

Articles included

The EBDJ usually categorises the articles into three main categories, ie editorials, toolbox articles and summaries.7 This study was restricted to the articles published as summaries. The sample consisted of summaries published in the EBDJ from the year 2004. Although the journal started in 1999 it was only recognised by Medline in 2004.

Variables

Year of publication and inclusion in the EBDJ

This objective was achieved by looking at the year the article was originally published and the year the article was included in the EBDJ. This variable helped determine if the journal provides up-to-date knowledge. Six electronic databases ie PubMed, EMBASE, Medline, TRIP, Cochrane library and Google Scholar were also searched to look for the specific article and the publication year which helped validate the information provided in the EBDJ.

Discipline within dentistry

To determine if the articles in the journal covered all fields equally within dentistry, this variable segregated the articles into different categories depending on the research question the paper asked. The title of each of the articles and the discipline mentioned on the upper right corner of the EBDJ article allowed categorisation into different disciplines within dentistry. However, there were instances when the two did not match, in which case the discipline from the title and abstract were mainly considered for data collection. The categories of disciplines used were as follows:

a. Restorative Dentistry

b. Prosthodontics

c. Orthodontics

d. Paediatric Dentistry

e. Periodontology

f. Oral Surgery

g. Oral Medicine and Radiology

h. Dental Public Health/Community Dentistry

i. Maxillofacial Surgery

j. Endodontics

k. Dental Materials

l. Oral Pathology

m. Others

If a research question was related to more than one discipline the primary discipline of the article was selected.

Type of study design

The abstract of the study and the title of the articles (in some cases) mentioned the study design, which helped identify the design and collect data using a specific criteria (Table 3). A thorough evaluation of the abstracts of each article was conducted to confirm the type of study design.

Level of expertise of the commentators in their respective fields

The commentary constitutes the concluding part of the articles in the EBDJ. As the commentary forms an integral part of the article, it is important to determine the level of expertise of the writers to assess if the commentary comes from a reliable source. The name of the commentators and their positions are mentioned at the end of the article before the list of references. This was used to record their names and positions using the criteria below. For some articles the commentator was listed as ‘anonymous’ as no details were provided in the journal. The articles were categorised into different categories according to the level of expertise of the commentators in their respective fields. These categories were as follows:

a. Academic

b. Members of Centres of Evidence-Based Dentistry in different countries

c. Dental practitioner

d. Hospital Dentists

e. Public Health practitioners

f. Others

Procedure

Two reviewers independently reviewed and assessed all the articles of the journal separately using a specifically designed data extraction form. There was also a discussion to assess the categories used for the articles and to resolve any form of disagreement between the reviewers. The analysis of the data was conducted in SPSS using descriptive statistical methods.

Results

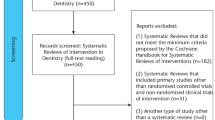

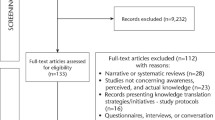

When the original search was carried out it identified 734 articles/summaries published in the EBDJ, out of which 149 articles were excluded after application of the inclusion criteria. Five hundred and eighty-six articles were found eligible and screened for further eligibility. Articles were excluded for more than one reason. From the eligible articles, three studies did not allow online access and thus although they were a part of the journal after 2004 (which is the basic inclusion criterion) they could not provide the needed information for data collection. For the remaining 582 studies, full articles were obtained for the study and were rendered eligible (as shown in Fig. 1).

Year of publication

For each of the included articles, the difference in the year the article was originally published and the year the article was included in the EBDJ was calculated. The difference in the number of years ranged from -1 to 3 years and the average of the difference in the number of years was calculated as 0.63 years (< 1 year). Two hundred and sixty-four articles were published in the EBDJ in the same year they were originally published. Two hundred and sixty-one articles were published one year after they were originally published. Forty-eight articles were included in the journal two years later; five articles were included three years later. For three articles it wasn't possible to determine the year they were actually published as the information was not available in the EBDJ and the articles could not be found on the databases mentioned above in the methods section. There were two articles which were first included in the EBDJ and then published in another journal. Table 1 shows the proportion of articles and the difference in the number of years.

Discipline of dentistry

One hundred and thirty-eight articles were categorised as dental public health; 107 pertained to periodontology. There were 69 articles from the field of orthodontics; 46 articles from oral medicine and radiology; 41 and 40 articles from paediatric and restorative dentistry respectively (Table 2). Thirty-six articles belonged to the discipline of oral surgery; 33 articles to endodontics; 31 articles from maxillofacial surgery; 27 from the discipline of prosthodontics. There were six from oral pathology and three from the field of dental materials. There were six articles identifying an association between medical and dental conditions and thus were added to the section ‘others’.

Study design

Four hundred and twenty articles (72.1%) were systematic reviews and 130 articles (22.3%) were randomised controlled trials (Table 3). The journal contained 11 guidelines and nine case-control studies. It had five cohort and two cross-sectional studies. The analysis also identified an in vivo study, health economic analysis, decision modelling analysis, an audit and a study distinguishing between the findings of a narrative review and a systematic review on a particular topic which were all included in the section ‘others’.

Level of expertise of the commentators

Most of the articles had one commentator, some of the articles had multiple commentators and each commentator was taken into consideration during data collection. Four hundred and fifteen articles had academicians as their first commentator (71.2%); 79 articles (13.6%) had commentaries from hospital consultants; 60 articles (10.3%) had commentaries from individuals working at the Centre of evidence-based dentistry (Table 4). Fourteen articles had private practitioners as their commentators and 10 articles had public health practitioners as their commentators (as shown in the table below). One article was categorised as ‘others’. Interestingly, the commentator of this article was identified as a member of a dental insurance company. Five articles in the EBDJ did not identify the commentators or their positions and thus they were recorded as ‘anonymous’.

Discussion

This systematic appraisal was conducted to determine if the Evidence-based Dentistry Journal acts as a reliable and contemporary source of knowledge for practitioners across all disciplines within dentistry. The results suggest that most of the articles included in the journal were either published in the same year or a year after they were originally published. Taking the individual and overall difference into consideration, it can be inferred that the journal publishes recent articles to allow readers to keep up to date with the continuously emerging scientific evidence. It can thus be considered as a contemporary source of knowledge to the readers/practitioners.

There was a considerable variation in the proportion of articles across various disc iplines within dentistry. This finding is in compliance with a similar study conducted by McKibbon and colleagues.6 They found that the broad-based disciplines like mental health had more titles compared to the more focussed disciplines like internal medicine.6 Similarly, this study found that the broad-based disciplines like dental public health, periodontology and orthodontics had more titles compared to the focussed disciplines like oral pathology and dental materials. But whether this difference in proportion reflects the difference in volumes of research published in each of the disciplines or a selection bias is yet unknown. One of the reasons for not including studies specific to dental materials could be the predominance of laboratory, rather than clinical studies in this field. The EBDJ should attempt to include a range of important articles from all disciplines within dentistry to act as a user's guide for readers specialising in different disciplines within dentistry.

The level of expertise of the commentators was used to assess the reliability of the commentary. Most of the commentators were academics or hospital consultants in the discipline the article concerned or members of the Centre of evidence-based dentistry. A minority comprised private practitioners and public health practitioners. However, there was one article identified in the category ‘others’ where the commentator of the article was an employee of a dental i nsurance company. Considering that the commentary influences decision-making in an evidence-based practice it seems potentially unethical to include a commentary written by a member of the insurance company. However, overall, the commentaries in the journal can be considered reliable and can be used to inform practitioners to make decisions in a clinical practice. The editorial team must ensure that commentaries written in the future are not from individuals with commercial interests.

Thus, on the whole the journal can be considered as providing reliable and contemporary evidence for evidence-based practitioners, however, not all disciplines within dentistry may have adequate coverage.

Limitations

While most of the information (regarding the article) provided by the journal was validated by obtaining the source articles, some articles could not be found and only the information provided by the journal was considered. Second, we used only the year of publication and not the month of publication. This might have led to an overestimation of the time difference between the year the article was published in the EBDJ and the year the article was originally published. Third, the titles for some articles were related to more than one discipline in which case only the primary discipline of the article was considered. This might have led to underestimation or overestimation of the proportion of articles in each discipline.

Summary of the recommendations

The journal is easily accessible, however, it failed to provide information on a small number of articles. Some articles had missing information with respect to the citation of the article, the author of the commentary and the position of the commentators. The team should try to report the level of expertise of the commentators more systematically for the readers and also ensure that the commentaries are written by individuals belonging to the dental field. In future, the editorial team should attempt to address this problem. The journal mentions the discipline on the top right corner for each of the articles, however, we observed that the discipline mentioned in the journal did not match the discipline in the title and this might confuse the readers/practitioners.

Conclusion

The commonly observed potential barriers to the implementation of EBH are the overload of evidence which directly influences decision making, the uncertainty of the intervention in practice and the limited time available to read the available literature on a particular condition.6,7,8,9 Evidence-based secondary journals like the EBDJ play an important role and can rightly claim to be a reliable and contemporary source of knowledge for evidence-based practitioners, however, not all disciplines within dentistry may have adequate coverage.

References

Centre for Evidence-Based Dentistry. About EBD [cited 2015 24/3/2015]. Available from: http://ebd.ada.org/en/about [Accessed 19 August 2016]

Richards D, Lawrence A . Evidence based dentistry. Br Dent J 1995; 179:270–273.

Allen D, Harkins KJ . Too much guidance? Lancet 2005; 365:1768.

Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA 1992; 268:2420–2425.

Gigerenzer G, Muir Gray J . (eds). Better doctors, better patients, better decisions: Envisioning health care 2020. Massachusetts: MIT Press; 2011.

McKibbon KA, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB . What do evidence-based secondary journals tell us about the publication of clinically important articles in primary healthcare journals? BMC Med 2004; 2:33.

Richards D . Evidence-Based Dentistry Journal [cited 2015 24/03/2015]. Available from: http://www.nature.com/ebd/index.html [Accessed 19 August 2016].

McGlone P, Watt R, Sheiham A . Evidence-based dentistry: an overview of the challenges in changing professional practice. Br Dent J 2001; 190:636–639.

Haines A, Donald A . Making better use of research findings. BMJ 1998; 317:72–75.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mehta, N., Marshman, Z. A systematic appraisal of the Evidence-Based Dentistry Journal. Evid Based Dent 17, 66–69 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401179

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401179