Key Points

-

Immediate replantation is recommended in case of avulsion of a permanent upper incisor.

-

First aid courses must emphasise the importance of prompt and appropriate dental trauma first aid management to improve prognosis following injuries.

-

Training must be held regularly in order to maintain knowledge and high confidence levels at all times.

Abstract

Objective To investigate awareness and practices of dental trauma first aid (DTFA) in hospital emergency settings and in primary and secondary schools in London.

Design A cross-sectional study using self-administered questionnaires and semi-structured interviews.

Setting Primary and secondary schools and casualty/emergency and walk-in casualty centres in London in 2005.

Subjects and methods A randomly selected sample of 125 schools and a total of 31 walk-in casualty centres, providing services for five randomly selected London boroughs. A person responsible for emergency care of children represented each of these study sites.

Results Response rates of 81.6% and 87% were achieved for schools and casualty/emergency centres respectively. The school respondents who had previously received advice on DTFA were three times more likely to be willing to replant an avulsed tooth compared to those who had not. A third of casualty personnel showed gaps in knowledge in DTFA. Results from schools showed an unwillingness to start emergency action mainly due to perceived inadequacy in knowledge/skills and also for legal reasons.

Conclusion There is the need for further studies focused on the barriers resulting in unwillingness to provide DTFA among school personnel and clarification regarding issues of responsibility and acceptable levels of competence of professionals other than dentists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Several epidemiological studies continue to show significant levels of dental trauma in many countries.1,2,3 The nature and complexity of dental trauma in children vary widely. In nearly all cases, prompt and appropriate management can significantly minimise the distress associated, and improve the prognosis of many of the resulting injuries.4 Although this is widely accepted within the dental profession, it is recognised that it is frequently a member of the lay public or other health professional who provides emergency care.5 It is nevertheless of the utmost importance that people who attend to injured individuals in the immediate period following dental trauma have the requisite knowledge and skill to provide dental trauma first aid.6,7

It has been reported that 16% of dental injuries eventually lead to tooth loss8 and could potentially result in complications such as alterations in a child's facial development and psychological changes.9 Injuries to the face are often the result of falls, sporting activities, road traffic accidents, fights, collisions, and non-accidental injuries. In the UK adolescent population, over a third of injuries occur at home and a further 25% at school.10 Several other studies have reported similar levels of injury at school and home.11

Dental trauma can vary from simple concussions to extensive maxillofacial damage involving periodontal structures and displacements or avulsion of teeth. Crown fractures form the most frequent type of injury, comprising 26-76% of injuries to the permanent dentition.12 Luxation injuries comprise 15-61% of all dental injuries13 and mainly involve maxillary central incisors. Pulp necrosis is an important sequela of all luxation injuries, its development depending on the type and severity of injury and stage of root maturation. Other sequelae include ankylosis, root resorption, root canal obliteration, and loss of marginal bone support.14 Although dental trauma varies widely in complexity, in most cases there is actually very little lay people or professionals other than dentists can do, apart from referring the affected individual for appropriate care at the dentist. Avulsion, however, is the one type of injury where lay people can play a crucial role in determining the prognosis of the tooth.

The complete detachment of the tooth from the socket through trauma (avulsion) is one of the most complicated dental injuries. It accounts for 1-16% of all traumatic injuries to the permanent teeth with the peak incidence recorded in the 7-11 year-old age group and the maxillary central incisors being the most affected.15,16 Boys experience avulsion three times more frequently than girls and avulsions are the most common type of dental injury for children less than 15 years of age seeking treatment in hospital emergency rooms.17 In the UK, children in primary and secondary schools are about 5-11 years and 11-18 years of age respectively.

It has been reported that immediate replantation is the best treatment for avulsion, giving success rates of 85-97% for healing of the periodontal ligament depending on stage of root development.18 This may require careful instructions given by a dentist or other qualified professional over the phone, to a person at the site of injury, to successfully carry out the replantation of a clean permanent tooth with an undamaged root.19 The patient should then be sent to a dental clinic as soon as is possible for further treatment (Fig. 1).

When immediate replantation is not feasible, such as if a child is uncooperative, there are several options for storage and transport to a clinic where replantation can be carried out.20 In the case of traumatic injury to the primary dentition, an avulsed primary tooth should not be replanted as the potential for damage to the developing tooth germ is very high.21,22

Although some previous studies have explored knowledge and/or practices of physicians, parents or teachers elsewhere, to our best of knowledge, there are currently no available data on London to inform current discussions on dental trauma first aid (DTFA).5,24 The present study will examine these issues in the two different settings simultaneously to enable the assessment of any patterns of similarity or otherwise. It will in particular investigate awareness and practices of dental trauma emergency care of these other relevant professionals.

Materials and methods

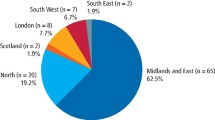

The study was piloted among five casualty/emergency personnel and five teachers chosen from sites other than those selected for the study. Only officially approved staff who had been at post for at least three months were included. Staff of non-operational casualty centres and personnel who declined to consent were excluded. Prior to the commencement of the study, ethical approval was obtained (REC ref. no: 04/Q0512/2), and permission was also sought from the Health and Educational heads in charge of the selected participants. The nature and purpose of study was explained to all participants, its voluntary nature emphasised, and strict confidentiality assured. Informed consent to participate was subsequently obtained from each study participant. Five London boroughs, three north of the River Thames and two in the south, were selected by a systematic random sampling procedure.

All hospitals with accident and emergency/casualty departments and walk-in centres providing services for the boroughs randomly selected were included in the study. In all, 31 sites within an average radius of 5.5 miles from the randomly selected boroughs were approached. Each casualty/emergency department was personally visited by the main investigator. Participants were invited to complete a questionnaire anonymously without consulting their colleagues.

The questionnaire comprised 11 questions, all but one being closed.23 The first section included questions aimed at collecting general demographic data. The second section, comprising nine closed questions, assessed the knowledge and treatment the participant intended to provide in cases of dental trauma (Fig. 2). These questions were essentially on avulsion and included what would be the appropriate emergency management and essential conditions for replantation, similar to the design utilised in a previous study.5

A sample size of 125 schools was estimated as providing a degree of precision of the results to within less than one percentage point. Following an initial telephone contact made to each selected school, a self-administered questionnaire with a total of 14 questions was mailed together with an information sheet, consent form, stamped self-addressed envelope and a brief personalised covering note for the head teacher of each participating school, for onward transmission to the selected teacher/staff member responsible for first aid. If the school had already recommended a staff member, this package was directly mailed to him/her. The questions generally followed a similar nature as that for the emergency and casualty centre participants and in addition enquired about any barriers to the provision of dental trauma first aid in cases of avulsion (Fig. 3).

A separate enquiry about the existence of any written guidelines/protocols on DTFA was also made in all sites studied, in order to assess responses in the light of current knowledge of best practice. The responses were entered into a personal computer and SPSS Version 12 software (Illinois, USA) was used for analysis and presentation of results. Statistical analysis carried out comprised descriptive statistics including estimation of proportions and frequencies. Significance was tested using the Chi-square test setting p <0.05 as being statistically significant.

Results

Casualty and emergency centres

Of the 31 sites included in the study, 27 participated in the study giving a response rate of 87%. Only a third (33.3%) of casualty/emergency respondents considered familiarity with emergency dental treatment as very essential. When asked about contraindications to replantation, 66.7% of respondents demonstrated knowledge consistent with current recommended guidelines (Table 1). The period of involvement with emergency care had no significant association with knowledge of DTFA in the present study (p = 0.123). No written protocols/guidelines on dental trauma first aid were identified in any casualty/emergency centre.

Schools

Of the 125 schools approached, 102 (70 primary and 32 secondary schools) completed the questionnaire representing a response rate of 81.6%. The present study showed only 28.4% had previous experience of avulsion and 51% had never been advised on the management of avulsion.

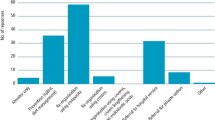

Nearly a third (31.4%) of school respondents did not know what to do in case of avulsion of an anterior permanent tooth. Although the majority of respondents (60.8%) were familiar with the contraindication of replantation of primary teeth, over 39% were either not knowledgeable or had limited knowledge in this matter. In spite of the fact that 60.8% of school respondents recommended immediate replantation in case of avulsion of an anterior permanent tooth, nearly two-thirds of respondents (62.7%) were unwilling to carry out replantation. The reasons indicated for their unwillingness to replant in the present study were mainly perceived lack of knowledge and legal reasons (Table 2). Only 36% of respondents alluded to need for an affected child to seek immediate attention from a dentist indicating a poor attitude to proper DTFA.

The period of involvement with first aid had no significant association with knowledge (p = 0.254) or willingness to carry out replantation in the present study (p = 0.901). There was a statistically significant relationship between the number of respondents who had previously received advice on DTFA and willingness to carry out replantation as shown in Table 3 (p = 0.010) with those having received advice being three times more likely to be willing to replant than those who had not received advice.

No written protocols/guidelines on dental trauma first aid were identified in any school.

Discussion

There was no significant variation in response rates as well as the correctness or otherwise of responses between boroughs in the present study. No significant variation was identified relating the period of involvement in emergency care to knowledge of DTFA among casualty/emergency and school personnel in the present study.

Casualty/emergency centres

When asked about replantation of avulsed permanent teeth, 74.1% recommended immediate replantation and 26.9% provided responses inconsistent with current guidelines. This is in marked contrast with findings of a study among similar emergency personnel in Israel indicating that only 4% would provide an appropriate initial treatment following avulsion.5

Satisfactory knowledge was demonstrated by most respondents regarding other aspects of management of avulsion of permanent teeth, such as suitable cleansing medium in case of tooth contamination (Table 1). This was investigated using a list of media similar to that reported previously.24 Gaps in knowledge were evidenced by the inability of nearly 15% of respondents to identify a suitable cleansing medium.

Awareness of the contraindication of replantation of primary teeth was demonstrated by only 66.7%. The current recommendation is that an avulsed primary tooth should not be replanted as the potential for damage to the developing tooth germ is very high.21,22

Only a third of respondents considered familiarity with dental trauma emergency treatment very essential. Though not specifically investigated in the present study, indications were that most casualty personnel when presented with avulsion would normally prefer to refer the patient to a maxillofacial or dental department. This is in spite of the obvious delay such action was bound to cause before replantation was eventually carried out.

Schools

It was interesting to note that more than half (52%) of the school respondents in the present study were welfare officers or in charge of first aid in their respective schools, but did not routinely supervise activities such as sports or children during break or meal times. This is at variance with findings elsewhere of over 74% and 90% of school staff supervising school sports and children during breaks and over the lunch period respectively.24

In the present study, 28.4% of school respondents had previous experience of avulsion, which was comparable to reports from a previous UK study24 but significantly higher than the 11.7% reported in Brazil.25 Findings showed that 51% of school respondents in the present study had never been advised on the management of avulsion. Furthermore, over 47% of those who claimed to have previously received advice were unable to state their source of advice.

Results of other specific questions testing knowledge revealed significant gaps in knowledge regarding certain key aspects of dental trauma first aid, such as the suitable cleansing medium for an avulsed tooth in case of contamination (Table 1). The recommended storage media include milk, physiologic saline, or saliva, either in the buccal sulcus of the mouth or in a container into which the patient spits. Whereas cold fresh milk appears to be the most favoured, neither ice or warm water is recommended,26 with the worst being dry storage.

Although 60.8% of school respondents indicated immediate replantation as an appropriate initial treatment for an avulsed tooth, only a third of respondents (37.3%) were willing to carry out replantation themselves. This was similar to earlier reports from other parts of the UK where more than 74% stated their unwillingness to replant an avulsed tooth themselves, with the main reason being lack of training.24

The present study clearly showed that respondents were three times more likely to replant avulsed teeth if they had previous advice on DTFA. Considering that the unwillingness to replant in schools was chiefly attributable to the perceived lack of skill and knowledge, the suggested need for educational campaigns aimed at improving knowledge and attitude towards DTFA cannot be over-emphasised.24 As previously recommended in Wales, the availability of individuals trained in dental first aid would be an effective way of reducing both the incidence and prognosis of dental trauma.27 The British Society of Paediatric Dentistry (BSPD) could play a vital role in emphasising the need for DTFA and provide trainers and/or literature for this purpose. An important role would be for the BSPD to liase with school first aid and casualty officers to ensure uniformity and clarity of literature prepared for use in schools and casualty units.

The fear of litigation was also noted as a significant barrier to starting first aid in schools. The respondents preferred contacting parents/guardians to collect their child and seek medical/dental attention elsewhere – rather than taking any physical action themselves. This may have been partly due to lack of knowledge and partly due to a wish to avoid touching in the present climate of no-touch policy amongst schools. The period of involvement of school personnel in first aid ranged widely from three months to over 10 years. More than half (51%) had been involved with first aid in their school for over five years. However, the period of involvement with first aid had no significance on knowledge or willingness to carry out replantation in the present study.

No written protocols/guidelines on DTFA were identified in any school or emergency/casualty centre. Three emergency/casualty centres, however, made reference to possible sources of such material. Although books and the internet were specifically cited, accessing the relevant DTFA information proved rather laborious when requests were made. In nearly all the sites approached there was an acknowledgement of the usefulness of such DTFA material being readily available for reference. Requests were made by the respondents for the publication and circulation of such material to all schools and casualty/emergency units, and for training. Earlier reports have indicated that in the UK, posters containing simple guidelines to be followed immediately after an avulsion injury and an advice sheet providing further details of the replantation technique and follow-up treatment for dentists were published in 1989 with over 200,000 distributed. Subsequently, several requests were made by medical practitioners and accident and emergency doctors.28,29 Although such educational campaigns were commendable, it is unclear if any evaluation of their effectiveness was carried out.29

In recognition of the important role played by other professionals in DTFA prior to a child's initial contact with a dentist, educational campaigns such as those held in countries such as Brazil, USA, Denmark and Australia have been attempted in parts of the UK previously.29 The findings of the present study suggest that such educational campaigns have either not had a wide enough coverage or have not been comprehensive enough. The apparent lack of evaluation of their effectiveness over the years has obviously been a major set back. Future educational campaigns must, in addition to addressing the above-mentioned shortcomings, also address problems relating to poor attitude to traumatic dental injuries, especially among sections of medical personnel working in casualty settings.

Conclusion

This study clearly has implications for the modification of first aid training, especially for first aid providers in schools and the education of casualty and emergency personnel. First aid courses must emphasise the importance of prompt and appropriate management improving the prognosis following traumatic dental injuries. Such training must be held regularly in order to maintain high knowledge and confidence levels at all times. Relevant DTFA posters suitably displayed in such casualty/emergency centres and school clinics is highly recommended. These should be updated in step with current evidence on DTFA.

There is a need for further studies focused on particular barriers that result in unwillingness to provide DTFA among school personnel. Clarification is required regarding issues of responsibility and acceptable levels of competence for professionals other than dentists, who may be expected to provide emergency care during the critical moments following traumatic dental injuries such as avulsion. It is hoped that the findings from this study will help to provide a basis for appropriate recommendations towards improving health outcomes following dental trauma in the community.

References

Hamdan M A, Rajab L D . Traumatic injuries to permanent anterior teeth among 12-year-old schoolchildren in Jordan. Community Dent Health 2003; 20: 89–93.

Kramer P F, Zembruski C, Ferreira S H, Feldens C A . Traumatic dental injuries in Brazilian preschool children. Dent Traumatol 2003; 19: 299–303.

Hamilton F A, Hill F J, Holloway P J . An investigation of dento-alveolar trauma and its treatment in an adolescent population. Part 1: the prevalence and incidence of injuries and the extent and adequacy of treatment received. Br Dent J 1997; 182: 91–95.

Andreasen J O, Andreasen F M, Skeie A, Hjorting-Hansen E, Schwartz O . Effect of treatment delay upon pulp and periodontal healing of traumatic dental injuries - a review article. Dent Traumatol 2002; 18: 116–128.

Holan G, Shmueli Y . Knowledge of physicians in hospital emergency rooms in Israel on their role in cases of avulsion of permanent incisors. Int J Paediatr Dent 2003; 13: 13–19.

Gregg T A, Boyd D H . Treatment of avulsed permanent teeth in children. UK national guidelines in paediatric dentistry. Royal College of Surgeons, Faculty of Dental Surgery. Int J Paediatr Dent 1998; 8: 75–81.

Kostopoulou M N, Duggal M S . A study into dentists' knowledge of the treatment of traumatic injuries to young permanent incisors. Int J Paediatr Dent 2005; 15: 10–19.

Walker A, Brenchley J . It's a knockout: survey of the management of avulsed teeth. Accid Emerg Nurs 2000; 8: 66–70.

Rocha M J, Cardoso M . Traumatized permanent teeth in Brazilian children assisted at the Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil. Dent Traumatol 2001; 17: 245–249.

Blinkhorn F A . The aetiology of dento-alveolar injuries and factors influencing attendance for emergency care of adolescents in the north west of England. Endod Dent Traumatol 2000; 16: 162–165.

Stockwell A J . Incidence of dental trauma in the Western Australian school dental service. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1988; 16: 294–298.

Andreasen J O, Ravn J J . Epidemiology of traumatic dental injuries to primary and permanent teeth in a Danish population sample. Int J Oral Surg 1972; 1: 235–239.

Andreasen J O . Etiology and pathogenesis of traumatic dental injuries. A clinical study of 1,298 cases. Scand J Dent Res 1970; 78: 329–342.

Dewhurst S N, Mason C, Roberts G J . Emergency treatment of orodental injuries: a review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998; 36: 165–175.

Fountain S B, Camp J H . Traumatic injuries. In Cohen S, Burns A C (eds) Pathways of the pulp. St Louis: Mosby, 1991.

Glendor U, Halling A, Andersson L, Eilert-Petersson E . Incidence of traumatic tooth injuries in children and adolescents in the county of Vastmanland, Sweden. Swed Dent J 1996; 20: 15–28.

Bhat M, Li S H . Consumer product-related tooth injuries treated in hospital emergency rooms: United States, 1979-87. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1990; 18: 133–138.

Andreasen J O, Borum M K, Jacobsen H L, Andreasen F M . Replantation of 400 avulsed permanent incisors. 4. Factors related to periodontal ligament healing. Endod Dent Traumatol 1995; 11: 76–89.

Trope M . Avulsion and replantation. Refuat Hapeh Vehashinayim 2002; 19: 6–15, 76.

Roberts G, Scully C, Shotts R . ABC of oral health. Dental emergencies. Br Med J 2000; 321: 559–562.

Andreasen J O, Andreasen F M . Textbook and color atlas of traumatic injuries to the teeth. 1st ed. pp 383–425. Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1994.

Garcia-Godoy F, Pulver F . Treatment of trauma to the primary and young permanent dentitions. Dent Clin North Am 2000; 44: 597–632.

Lowe D . Planning for medical research: a practical guide to research methods. Cleveland: Astraglobe, 1993.

Blakytny C, Surbuts C, Thomas A, Hunter M L . Avulsed permanent incisors: knowledge and attitudes of primary school teachers with regard to emergency management. Int J Paediatr Dent 2001; 11: 327–332.

Pacheco L F, Filho P F, Letra A, Menezes R, Villoria G E, Ferreira S M . Evaluation of the knowledge of the treatment of avulsions in elementary school teachers in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Dent Traumatol 2003; 19: 76–78.

Andreasen J O, Hjorting-Hansen E . Replantation of teeth. I. Radiographic and clinical study of 110 human teeth replanted after accidental loss. Acta Odontol Scand 1966; 24: 263–286.

Dental Public Health Unit. Promoting oral health - an integrated approach for Wales. Cardiff: Health Promotion Wales, 1996.

Mackie I C, Blinkhorn A S . It's a knock-out - the avulsed tooth. Colgate Dental News 1989; 6: 1–4.

Hamilton F A, Hill F J, Mackie I C . Investigation of lay knowledge of the management of avulsed permanent incisors. Endod Dent Traumatol 1997; 13: 19–23.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Addo, M., Parekh, S., Moles, D. et al. Knowledge of dental trauma first aid (DTFA): the example of avulsed incisors in casualty departments and schools in London. Br Dent J 202, E27 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2007.328

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2007.328

This article is cited by

-

'He was distraught, I was distraught.' Parents' experiences of accessing emergency care following an avulsion injury to their child

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Initial management of paediatric dento-alveolar trauma in the permanent dentition: a multi-centre evaluation

British Dental Journal (2010)