The enigmatic space rock 'Oumuamua shot through the Solar System in 2017. Credit: European Southern Observatory/Science Photo Library

‘Oumuamua is best known as the interstellar visitor that flew through the Solar System in 2017, a cosmic rock on a temporary visit from deep space. But it is also blazing a trail in connecting Hawaiian Indigenous culture with modern astronomy.

In the Hawaiian language, ‘Oumuamua means “a messenger from afar arriving first”, a reference to its scout-like nature. Astronomers and the public adopted the name quickly. Now, the experts who came up with it are developing names for other celestial objects discovered using Hawaii’s world-class telescopes.

The team includes experts in Hawaiian culture and astronomy. It hopes to strengthen the links between the Hawaiian language, which has gone from nearly extinct to a vibrant source of cultural identity, and astronomical findings with ties to the island chain. The International Astronomical Union (IAU), which approves official celestial names, is considering two more Hawaiian-language submissions from the project, which describe two unusual asteroids.

“A name isn’t just something by which we call something or someone,” says Ka’iu Kimura, executive director of the ‘Imiloa astronomy and cultural-education centre in Hilo, Hawaii, where the effort is based. “A name provides identity and gives insight.” She unveiled the project on 7 January at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle, Washington.

What’s in a name

The effort is called A Hua He Inoa, a Hawaiian phrase that references the practice of calling forth a name. It is not directly related to the ongoing controversy over building a next-generation observatory, the Thirty Meter Telescope, atop the Mauna Kea mountain on Hawaii’s Big Island. But it does try to address the decades-long dispute over whether astronomers have properly developed and managed observatories on Mauna Kea and other peaks that are sacred to Native Hawaiians.

“This is a way to flip the whole controversial conversation on its head,” says Kimura.

It is a rare example of connecting modern Indigenous culture with local astronomical discoveries, says Doug Simons, the director of the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope on Mauna Kea, who is part of the naming project.

Ka’iu Kimura is a leader of A Hua He Inoa, an effort to bestow Hawaiian-language names on Solar System objects.

The concept arose in March 2017, when Hawaiian businessman John De Fries suggested that the cultural group that advises Mauna Kea’s management propose Hawaiian-language names for local discoveries to the IAU. “I was interested in understanding how we could elevate the nature of astronomers’ work on the mountain, to a level that would embrace the origins that Hawaiians understood themselves to come from,” he says.

De Fries then met with Kimura and Simons. The team was beginning to grow when, in October 2017, astronomers on the Hawaiian mountain of Haleakalā discovered the interstellar space rock. “That was the pivotal moment,” says Simons. It was an entirely new class of object that would require an entirely new type of name from the IAU — the chance they didn’t know they had been waiting for.

Kimura called her uncle Larry Kimura, a professor of Hawaiian language and studies at the University of Hawaii in Hilo who spearheaded the language’s revitalization. The next day he called back to suggest the name ‘Oumuamua.

Living language

Now, the team is building on that first example. “The opportunity to name this interstellar object that literally hurled through our Solar System equally hurled us an opportunity to test our effort,” says Kimura.

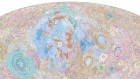

A Hua He Inoa aims to create Hawaiian names on demand. Last October, Kimura and her colleagues gathered 10 high-school and college students, all fluent in the Hawaiian language, and gave them two unusual asteroids to name. The first — an apparent fragment of a larger asteroid — was given the name Kamo‘oalewa, which refers to an offspring that travels on its own. The second, which travels in a peculiar backwards orbit near Jupiter, garnered the name Ka‘epaoka‘āwela, which refers to its mischievous behaviour. Both names are awaiting the IAU’s approval.

“There’s so much in language,” says Aparna Venkatesan, an astronomer at the University of San Francisco in California. “It’s a way to teach a new generation of scientists about humanity’s shared heritage.”

Starting on 18 January, Kimura and her colleagues will be offering Hawaiian-language lessons to staff members at any of the observatories on Mauna Kea or Haleakalā. Later this year, they plan to convene a group of teachers from Hawaiian-language schools to generate names for more asteroids.

Kimura hopes astronomers outside Hawaii will support the effort. “If they’re using data from Hawaii, we hope they will see the importance of recognizing the place,” she says. “There’s already a connection.”

The mountain-top battle over the Thirty Meter Telescope

The mountain-top battle over the Thirty Meter Telescope