Medicines regulators, including Emer Cooke (left), the director of the European Medicines Agency, and Stephen Hahn, the commissioner of the US Food and Drug Administration, have an opportunity to further harmonize regulatory processes.Credit: European Medicines Agency, FDA

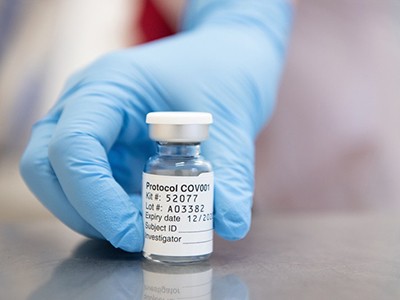

The roll out of COVID-19 vaccines is under way, but without, it seems, much global coordination. China, Russia and the United Arab Emirates began administering vaccines before the conclusion of clinical trials. Last week, the United Kingdom issued emergency approval for a vaccine developed by the US biopharmaceutical company Pfizer and BioNTech of Mainz, Germany, following positive results from phase III testing. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has needed longer to make its decision on the same vaccine. And the regulatory agencies of Australia, the European Union and Switzerland are taking longer still.

This patchwork of approvals processes, despite COVID-19 being a common enemy, has revived a long-standing question about how to accelerate harmonization in vaccine regulation. Researchers reviewing the regulatory landscape found at least 51 pathways to various types of accelerated vaccine approval in a group of 24 countries1.

Greater harmonization would bring many benefits. Drug companies could look forward to agreed definitions for different types of approval, and would benefit from agreed guidelines for criteria that their vaccine candidates would need to meet. If regulators were to ask for broadly the same things, companies could cut the time needed to prepare their drug applications. Companies, for their part, would need to allow — or help to create — a secure way for regulators to share data, which they are often not permitted to do at present.

The COVID vaccine challenges that lie ahead

By assessing the same data, regulators could more easily compare their findings and analyses with those of others, and their decisions would not only be more robust, but also be seen to be more robust. That, in turn, would shore up public confidence in a world in which vaccine hesitancy is rising and in which many citizens already have the means to compare regulatory verdicts. This would be an evolutionary shift, not a revolutionary one, because in recent years — and particularly since the 2014–16 Ebola crisis — regulators have made unprecedented efforts to discuss, coordinate and begin to harmonize some of their processes.

The FDA, which was set up in 1906, is the world’s oldest national medicines regulator. But the world has been moving towards greater regulatory coordination for some time. Europe’s regulatory system comprises a network of 50 national bodies from 31 European countries. The European Medicines Agency (EMA), created in 1995, sits at the centre of this network. All countries have their own medical regulators, but the EMA provides manufacturers with a single place for scientific evaluation of drug applications, if they want Europe-wide approval.

Although EMA and FDA verdicts are often broadly similar, the authorities differ in key ways. For example, the FDA requires drug companies to submit all the raw data from laboratory, animal and human trials so that it can do its own statistical analysis. By contrast, the EMA relies more on drug companies’ own analyses.

In other regions — Africa, for example — countries are also inching towards an approach that allows for the pooling of regulatory expertise. This is the purpose of the African Vaccine Regulatory Forum, set up in 2006.

Why emergency COVID-vaccine approvals pose a dilemma for scientists

And at the global level, in 2012, the member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) agreed to establish the International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities (ICMRA) to allow regulators to share information and agree on approaches. The ICMRA has 29 members, including regulators from China, Europe and the United States. Through it, members have been able to reach a consensus on the best animal models for testing COVID-19 vaccines, the ideal clinical-trial end points and the complicated issue of continuing placebo-controlled trials after vaccine roll out begins. The coalition’s COVID-19 working group is now trying to harmonize the monitoring of vaccines once they have been deployed, because faint signals of adverse effects might be too weak to spot in any one country.

And then there is the WHO itself. Low- and middle-income countries can now benefit from the work that goes into its Emergency Use Listing (EUL) process. On 13 November, the agency issued its first ever such vaccine listing, for a polio vaccine. National regulators still need to decide whether this vaccine is right for their country, but a recommendation from the WHO — and confidence in its assessment process — means that most are likely to follow its advice.

Around the end of October, the WHO requested that both the FDA and the EMA assess the suitability of COVID-19 vaccines for low- and middle-income countries as they consider whether to issue emergency authorizations. It is not clear whether the regulators will agree — but if either does, the WHO can draw on that analysis and issue its own EUL within days of the decision. That would be collaboration indeed.

COVID vaccine confidence requires radical transparency

These are all important and necessary efforts. The need now is to go one step further and find a path through the many different types of vaccine approval. Before the pandemic, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, a global group of funding agencies, companies and non-governmental organizations, set up a working group to map out obstacles to better global regulatory alignment, in anticipation of a new infectious disease. This process confirmed how regulatory agencies differ on issues such as the use of genetic modification in vaccine development, clinical trials in pregnant women, and even vial labelling. But it also meant that inconsistencies were already mapped out and under discussion when the pandemic struck. COVID-19 has intensified these discussions.

The next step will not be easy. Regulators want to be able to exchange data. Their experiences during the pandemic have convinced many that they are moving towards a point at which this will be possible. They want to be able to talk to each other in the same units and about the same end points, and to make decisions based on the same data.

Ultimately, each country must make its own decisions about what’s best. But the goal of a harmonized regulatory dossier for vaccines, conforming to an agreed set of international regulatory requirements, would be transformative.

The COVID vaccine challenges that lie ahead

The COVID vaccine challenges that lie ahead

Why emergency COVID-vaccine approvals pose a dilemma for scientists

Why emergency COVID-vaccine approvals pose a dilemma for scientists

COVID vaccine confidence requires radical transparency

COVID vaccine confidence requires radical transparency