Abstract

The aim of the European Board of Medical Genetics has been to develop and promote academic and professional standards necessary in order to provide competent genetic counselling services. The aim of this study was to explore the impact of the European registration system for genetic nurses and counsellors from the perspectives of those professionals who have registered. Registration system was launched in 2013. A cross-sectional, online survey was used to explore the motivations and experiences of those applying for, and the effect of registration on their career. Fifty-five Genetic Nurses and Counsellors are registered till now, from them, thirty-three agreed to participate on this study. The main motivations for registering were for recognition of their work value and competence (30.3%); due to the absence of a registration system in their own country (15.2%) and the possibility of obtaining a European/international certification (27.3%), while 27.3% of respondents registered to support recognition of the genetic counselling profession. Some participants valued the registration process as an educational activity in its own right, while the majority indicated the greatest impact of the registration process was on their clinical practice. The results confirm that registrants value the opportunity to both confirm their own competence and advance the genetic counselling profession in Europe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the context of healthcare, having a qualified workforce is essential to provide appropriate patient care. This requires individual health professionals to have the capacity for assimilation of and adaptation to new approaches to enable patients to benefit from innovations such as advances in diagnostic, preventative and therapeutic advances is clinical genetics.1

Traditionally, a medically led field, clinical genetics, has evolved into a multidisciplinary service, where other non-medical allied health professionals, such as specialised genetic nurses and genetic counsellors, are also key players in the delivery of high-quality patient care.2, 3 This has arisen partly in response to the expansion of the need for these services.4 Genetic nurses and counsellors combine expertise in medical genetics with the ability to communicate scientific information in an empathetic manner to patients and their families.5

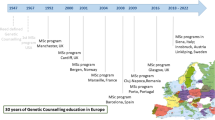

In a young but quickly evolving field such as genetic counselling, professional registration is especially relevant. Registration is a formal process based on achievement of a set of competencies, following a periodic evaluation based on agreed standards.6 While the registration system at European level was established in 2013,3 there are countries with a longer tradition of professional registration in the field of genetic counselling such as the USA (since 1982), Australia (1989), Canada (1998) and the United Kingdom (2001).7 Unfortunately registration is not an option in the majority of European countries.8, 9, 10

The journey to the establishment of a European registration system has been published elsewhere.3 While the process has been assessed informally, there has been no previous formal evaluation of the impact of the European registration system from the perspectives of those registered professionals. The objectives of this study were to explore: (1) the experiences of those applying for registration; (2) their motives for registering; and (3) the effect of registration on the individual’s career.

Materials and methods

Design

We undertook a descriptive, cross-sectional online survey inviting all registered professionals (n=55) to participate. Detailed methods are included in the Supplementary Material.

Results

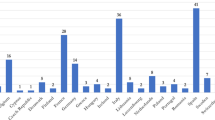

Thirty-three European Registered Genetic Nurses and Counsellors responded to the survey (61.0% response rate): demographic details and information about their background and route of access for registration are presented in Tables 1, 2 and Figure 1.

In an open question regarding motivation for registering, participants were asked to comment on their main motivation; 30.3% (n=10) of the respondents considered the registration would be relevant for their career development and as a recognition of their work value and competence, 9 (27.3%) registered to obtain a European/international certification and for 6 (15.2%), registration was important because of the absence of a registration system in their own country. Nine (27.3%) registered to support the process and/or collaborate in the development of the genetic counselling profession. Four (12.1%) respondents considered registration would be valuable to seek other job opportunities in another European country.

The majority (60.6%, n=20) of the participants agreed that the registration process was very straightforward. However 27.28% (n=9) of the participants found it laborious and time consuming. Four (12.1%) reported that the registration process was interesting and insightful and reported satisfaction in gaining an overview of their own work. The major challenge reported was time allocation for registration (18.2%, n=6). Anonymized quotes of participants’ opinion on the registration process are in the Supplementary Material.

As to professional status, participants felt that registration gave them credibility among colleagues and enhanced their professional visibility. Some of the participants valued the registration process as an educational activity in its own right, by reflection on their own practice and continuing professional activities, as well as consideration of ethical issues of daily practice. Some participants felt that the case log requirement of 20% cases outside of their specialty area was a challenge that allowed them to re-connect with other areas of genetics. The majority (84.4%, n=28) had already felt an impact on their clinical practice and 66.7% (n=22) on their career development, while 5 (15.5%) stated the registration had not yet had any tangible impact on their professional activity.

As to the impact of European registration on national genetic counselling systems, 39.4% (n=13) felt European registration had an impact. While some felt that the European acknowledgement of the profession would support them to seek more recognition at national level, others stated the role of the genetic counsellor was not yet recognised in their country. One respondent reported that they had used the EBMG registration to start a dialogue with their government. Respondents originating from countries that already had a national system of registration felt that, to be registered was less useful to them unless they were likely to work out of their home country or work in a country without a pre-existing registration system.

A further indication of support for the process was the response that 78.8% (n=26) of respondents would recommend, or strongly recommend registration to their colleagues, while only one participant would not. The general feeling was one of momentum—the process would be recommended to gain a critical mass to give ‘the tools to defend our profession as recognised professionals ’.

When asked the relevance of the registration system to improving standards of genetic counselling practice in Europe, 81.8% (n=27) of respondents felt that the registration system was important or very important to improving standards, 12.1% (n=4) remained neutral, while 6.1% (n=2) felt that the registration system was unimportant to practice standards.

Discussion

As the vast majority of European countries do not yet have national registration systems or guidelines advising the training and practice standards of genetic counsellors,10 we believe the European registration system has made a contribution to the further development and adoption of best practice and training models. The wide range of countries from which we have received applications throughout the past 3 years and the enthusiastic acknowledgment of the standards and relevance of the European registration for genetic nurses and counsellors reflects the importance it has for genetic healthcare services in Europe. However, as indicated by the results of our study, the registration process is not without considerable challenges.

One challenge attributed to the registration process was related to the request of at least 10 cases from outside applicant’s areas of specialisation. This requirement was set up on the light of the new areas where genetic counsellors are increasingly contributing such as cancer genetics, prenatal diagnosis, cardiac genetics as well as diagnostic laboratories, and with the aim of ensuring registered professionals are competent to practice beyond specific specialist settings, similar systems operating in Canada, Australia and the USA.11, 12

Acceptance and support of genetic counsellors’ practice standards by medical geneticists can be a challenging process in countries where the establishment of the profession is at an early stage.12 Further exploratory studies may contribute eliciting the views of medical geneticist colleagues about the registration process and the impact it has on local genetics healthcare services.

The competencies-based register we have developed can also contribute to future growth of genetic counselling profession in those countries through the promotion of interdisciplinary understanding, giving more visibility to the roles and added value of genetic nurses and counsellors to the teams. Within the genetic counselling context in Europe, registration additionally could mean a step towards more flexible access to European job options for registered genetic counsellors, as it seems is already the case for some participants in the present study.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Although the response rate was good, this was a study with small numbers of respondents due to the limited number of registrants. As a number of registered professionals did not participate in this study, we may have missed potential relevant data on the process. Professionals deciding not to participate may be those who were not satisfied with the process or felt it was unhelpful and, hypothetically, not motivated to complete the survey.

Conclusions

Developing a registration system that addresses the needs of practitioners in countries with different educational, cultural and legal systems was a challenging task. The results of this survey have confirmed that registrants value the opportunity to both confirm their own competence and advance the genetic counselling profession in Europe.

References

Battista RN, Blancquaert I, Laberge A-M, van Schendel N, Leduc N : Genetics in health care: an overview of current and emerging models. Public Health Genomics 2012; 15: 34–45.

Skirton H, Barnes C, Curtis G, Walford-Moore J : The role and practice of the genetic nurse: report of the AGNC Working Party. J Med Genet 1997; 34: 141–147.

Paneque M, Moldovan R, Cordier C et al: Development of a registration system for genetic counsellors and nurses in health-care services in Europe. Eur J Hum Genet 2016; 24: 312–314.

Hannig V, Cohen M, Pfotenhauer J, Williams M, Morgan T, Phillips J : Expansion of genetic services utilizing a general genetic counseling clinic. J Genet Couns 2014; 23: 64–71.

McAllister M, Payne K, Macleod R, Nicholls S, Donnai D, Davies L : What process attributes of clinical genetics services could maximise patient benefits? Eur J Hum Genet 2008; 16: 1467–1476.

Authority PS : Independent quality mark for Genetic Counsellors 2016, Available at: http://www.professionalstandards.org.uk/latest-news/latest-news/detail/2016/06/15/independent-quality-mark-for-genetic-counsellors (accessed 1 November2016).

Skirton H, Kerzin-Storrar L, Patch C et al: Genetic counsellors: a registration system to assure competence in practice in the United kingdom. Community Genet 2003; 6: 182–183.

Cordier C, Lambert D, Voelckel M-A, Hosterey-Ugander U, Skirton H : A profile of the genetic counsellor and genetic nurse profession in European countries. J Community Genet 2012; 3: 19–24.

Skirton H, Cordier C, Lambert D, Hosterey Ugander U, Voelckel M-A, O’Connor A : A study of the practice of individual genetic counsellors and genetic nurses in Europe. J Community Genet 2013; 4: 69–75.

Skirton H, Cordier C, Ingvoldstad C, Taris N, Benjamin C : The role of the genetic counsellor: a systematic review of research evidence. Eur J Hum Genet 2015; 23: 452–458.

McEwen AR, Young MA, Wake SA : Genetic counseling training and certification in Australasia. J Genet Couns 2013; 22: 875–884.

Ferrier RA, Connolly-Wilson M, Fitzpatrick J et al: The establishment of core competencies for canadian genetic counsellors: validation of practice based competencies. J Genet Couns 2013; 22: 690–706.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paneque, M., Moldovan, R., Cordier, C. et al. The perceived impact of the European registration system for genetic counsellors and nurses. Eur J Hum Genet 25, 1075–1077 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2017.84

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2017.84

This article is cited by

-

The role of the Genetic Counsellor in the multidisciplinary team: the perception of geneticists in Europe

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)

-

Building awareness on genetic counselling: the launch of Italian Association of Genetic Counsellors (AIGeCo)

Journal of Community Genetics (2020)

-

The Global State of the Genetic Counseling Profession

European Journal of Human Genetics (2019)