Abstract

Objective:

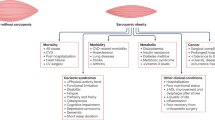

There is debate as to the effects of obesity on the developing feet of children. We aimed to determine whether the flatter foot structure characteristic of obese primary school-aged children was due to increased medial midfoot plantar fat pad thickness (fat feet) or due to structural lowering of the longitudinal arch (flat feet).

Methods and procedures:

Participants were 75 obese children (8.3±1.1 years, 26 boys, BMI 25.2±3.6 kg m−2) and 75 age- and sex-matched non-obese children (8.3±0.9 years, BMI 15.9±1.4 kg m−2). Height, weight and foot dimensions were measured with standard instrumentation. Medial midfoot plantar fat pad thickness and internal arch height were quantified using ultrasonography.

Results:

Obese children had significantly greater medial midfoot fat pad thickness relative to the leaner children during both non-weight bearing (5.4 and 4.6 mm, respectively; P<0.001) and weight bearing (4.7 and 4.3 mm, respectively; P<0.001). The obese children also displayed a lowered medial longitudinal arch height when compared to their leaner counterparts (23.5 and 24.5 mm, respectively; P=0.006).

Conclusion:

Obese children had significantly fatter and flatter feet compared to normal weight children. The functional and clinical relevance of the increased fatness and flatness values for the obese children remains unknown.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

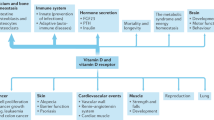

As feet are the body's base of support, healthy foot structure is critical for efficient posture and ambulation. Studies investigating the effects of obesity during childhood on the development of foot structure have typically used an indirect measure, that of footprints, to suggest that the feet of young obese children are characteristically flatter relative to their leaner counterparts.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 This flatter foot appearance has been assumed to be a function of lowered arches within the feet, which, in turn, may lead to musculoskeletal disorders and pain in the back and lower limbs of obese children and adolescents.6, 7 There is growing debate in the literature, however, as to whether this flatter foot structure does actually constitute lowered arches.

One suggestion is that the flatter feet characteristic of obese children may be caused merely by the existence of a thick plantar fat pad underneath the medial midfoot, giving the appearance of a flat foot due to greater ground contact.4 Although a fat pad is typically present under the medial aspect of the feet of infants at birth, this fatty pad is thought to disappear in the juvenile foot between 2 and 6 years of age after major developmental changes in the medial arch contour.8, 9 A recent study confirmed thicker fat padding in the feet of obese, compared to overweight, school-aged children, although as the between-group difference was small, no functional relevance was attributed to this increased fat pad thickness.10 However, in a study comparing preschool children,3 no difference in medial fat pad thickness was found between overweight/obese and non-overweight participants. As significant between-group differences were evident in external arch height measures in these two previous studies, the authors postulated that obese children's feet were structurally flatter, rather than fatter, than their leaner counterparts. Limitations of these studies, however, included small sample sizes, the absence of normal weight control participants in the first study, and the participants’ young age (mean age 4.3 years) confounding interpretation of the results in the second study.

To our knowledge, no study has systematically investigated medial midfoot fat padding and medial longitudinal arch height in the feet of a large sample of lean and obese children aged more than 5 years. Therefore, in this study we aimed to determine whether, in comparison with normal weight children, the flatter foot structure characteristic of obese school-aged children was due to increased medial midfoot plantar fat pad thickness (fat feet) or due to structural lowering of the longitudinal arch (flat feet).

Methods

Participants

Participants in this study were recruited by two strategies. The first involved a cohort of children who had volunteered to participate in a multisite randomized controlled trial of a combined physical activity skill-development and dietary modification program among overweight and obese children;11 in this case, measurements were taken at baseline. In addition, four local independent schools granted permission to recruit children in kindergarten to year 3. From these two samples, all obese children (n=75) were selected as experimental participants, with 75 non-obese children, matched for age and sex to the obese children, selected as control participants. As arch height was measured in this study, and this foot parameter is believed to be formed by about 6 years of age,8, 9 only data for children who were 6 years or older were analyzed and included in the results.

All measurements were collected at either the University of Wollongong or the child's school. The University of Wollongong Human Research Ethics Committee approved all study procedures (HE05/010) and parents gave written, informed consent for their children to participate in the study. All children gave verbal consent to participate.

Anthropometry

Participants had their standing height and body mass recorded while wearing lightweight clothing. Standing height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a Seca 214 portable stadiometer (Seca Corp., Hanover, MD, USA) and a set of UC-321 Home Health Care Scales (A&D Weighing Pty Ltd., Thebarton, SA, Australia) was used to measure body mass to the nearest 0.01 kg. The mean scores of two height and two body mass measurements were used to calculate body mass index (BMI; weight/height2). If measurements differed by more than 3 mm, a third measure was taken and the closest two measures were used to calculate the mean score. The classification system proposed by Cole et al.,12 based upon BMI, was used to determine children's weight status.

External foot measures

Foot length, ball of foot length, instep length, ball of foot breadth, heel breadth, ball of foot height, dorsal arch height, plantar arch height, ball of foot circumference and instep circumference were measured for both feet of each participant to the nearest millimeter. All anthropometric foot measurements13 were recorded by the chief investigator (DLRH) using a combination level (Stanley Tools, New Britain, CT, USA), a metal tape (KDS Corp., Kyoto, Japan), small anthropometer (Lafayette Instrument Co., Lafayette, IN, USA) and a custom-designed foot tray. Specifically, the plantar arch height was measured from the supporting surface to the lowest medial foot protrusion at the instep landmark.13 Two measurements (three, if values differed by 3 mm) were taken while participants stood barefoot with equal weight on both feet. The mean score was used in later analysis to represent each foot dimension.

Internal foot measures

A portable SonoSite 180PLUS ultrasound system (Bothell, WA, USA) with a 38 mm broadband linear array transducer (10–5 MHz, 7 cm maximum depth) was used to quantify plantar fat pad thickness (mm) in the medial midfoot region of each child's right and left feet.14 A linear transducer with a high frequency was selected as it provides a uniform, wide field of view with a superior near-field resolution for imaging superficial structures,15 such as adipose tissue. Ultrasound was selected as it was noninvasive, portable for use in the field and did not involve radiation.

Non-weight-bearing plantar fat pad thickness was assessed while each child was seated with their leg extended and foot resting in a relaxed position on the lap of the chief investigator (DLRH), who took all measurements. To standardize the site at which the midfoot plantar fat pad thickness was assessed, we placed the ultrasound probe longitudinally, vertically below the dorsal navicular landmark on the plantar surface of the foot and aligned with the second metatarsal. When a clear image was attained, the system was paused and the thickness of the fat pad was quantified (accuracy=0.01 cm) using the measurement function of the ultrasound system (Figure 1). Three trials were collected with the mean thickness value per foot taken as representative of left and right medial midfoot plantar fat pad thickness. Weight-bearing fat pad thickness and internal arch height were assessed following the same protocol but with the children standing on a custom-designed Perspex platform. Internal arch height, measured at the same site as the fat pad thickness measurement, was the distance from the supporting surface of the platform to the joint beneath the dorsal navicular landmark. Children were assisted onto the platform and focused on a picture placed directly in front of them and at eye level. They were instructed to stand with equal weight on each foot and their hands at their sides. The probe was held in a cutout section (80 × 25 mm) of the platform surface, which allowed the probe to be placed level with the supporting service of the platform to image the child's medial midfoot while they were standing (Figure 2). Extensive reliability testing of this novel method was performed on 3 consecutive days, three times per foot, for 14 children unassociated with this study. Intraclass correlation coefficients16 on the between-day values ranged from 0.82 to 0.91, confirming the method provided highly reproducible values.14

Statistical analysis

Initial analysis of the data revealed limited significant differences in the outcome variables between the right and left feet of each child. Therefore, data for the left foot were selected as representative of each child's foot structure, and data pertaining to that foot were included in the statistical analyses for between-subject group comparisons. Means and standard deviations for each variable were calculated for the two subject groups. Data were tested for normality using a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (with Lilliefors’ correction) with a Mann–Whitney t-test used if the assumption of normality was violated. Independent t-tests were then computed on data obtained for the obese children relative to the non-obese children to determine whether there were any significant differences (P⩽0.05) in the outcome variables characterizing foot structure between the two subject groups. The software package SPSS 15 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform all statistical analyses.

Results

As can be seen in Table 1, the obese children were significantly taller with a greater BMI compared to the non-obese children, yet there was no difference in age that ranged from 6. 4 to 9.9 years. Table 1 also shows the external foot anthropometry for the two groups, and internal foot measures are shown in Figure 3. As anticipated, the obese children's feet displayed significantly greater values for all lengths, breadths, heights and circumferences when compared to the feet of the non-obese children. The only external foot anthropometric measurement not significantly different between the two groups was plantar arch height (Table 1).

Both the non-weight-bearing and weight-bearing medial midfoot fat pads were significantly thicker in the obese children compared to their leaner counterparts, whereas the internal arch height was significantly lower in the feet of the obese children (Figure 3).

Discussion

In this study, we examined foot dimensions in primary school-aged children to determine whether obese children displayed increased plantar fat pad thickness or lowered medial longitudinal arches compared to their leaner counterparts. Significant differences were found in almost all foot measurements between the obese and non-obese children.

External foot measures

Previous investigation of school-aged children has confirmed that obese children have larger foot dimensions when compared to their non-overweight peers,2 findings that are consistent with results from this study. However, unlike younger overweight and obese children,3 the obese children in this study had significantly higher feet relative to the feet of the non-obese children. The obese children's feet were higher at the point where the upper surface of the foot meets the leg (dorsal arch) and also higher at the front of the foot (ball of foot). It could be assumed that if the tops of the obese children's feet were significantly higher than their leaner counterpart's feet then their plantar arches should also be significantly higher. However, the height of the plantar arch was similar in both groups. This suggests either a lowering of the midfoot arch or advanced bone structure development in the feet of obese children relative to leaner children, although evidence on this latter explanation is still conflicting.17

Numerous studies have attempted to address the issue of comparing medial longitudinal arch height between subject groups by normalizing arch height to foot length or truncated foot length to produce an arch index.18, 19 Because of the significant differences in 9 of the 10 foot anthropometry measures between the two groups in this study, plantar arch height (the only nonsignificant value) was divided by truncated foot length to further investigate this finding. When normalized to truncated foot length, the plantar arch index was significantly less in the obese children compared to the non-obese children (mean±s.d., 0.085±0.018 and 0.098±0.017, respectively, P<0.001). This indicates that even though the obese children had a higher foot, they also had a lower medial midfoot compared to the non-obese children. On first inspection, these results appear to confirm the notion that obese children's feet are flatter than their non-obese counterparts. However, the question then arises as to whether external medial midfoot height, an indirect measurement, is a good indication of bone height and, in turn, representative of flatter feet in the obese participants, or is this measure influenced by additional adipose tissue in this region of the foot, indicating that the obese children's feet were just fatter?

Internal foot measures

This is the first study to quantify and report midfoot plantar fat pad data for a relatively large sample of lean and obese school-aged children. Similar to results reported previously for both preschool children,3 and overweight and obese school-aged children,10 all children in this study, irrespective of their BMI, displayed a midfoot plantar fat pad, with the thickness of this fat pad ranging from 2.9 to 6.9 mm. Therefore, we are able to confirm that, in contrast to speculation in the literature,8, 9 the plantar fat pad does not disappear in the juvenile foot after developmental changes in the medial arch contour.

The difference in non-weight-bearing medial midfoot fat pad thickness between the two groups (mean difference of 0.5 mm) was the same as that previously reported between overweight and obese children,10 confirming that the obese children had fatter feet relative to their non-obese counterparts. A study in younger children (mean age 4.3 years) showed an insignificant difference of 0.2 mm between obese and non-obese participants.3 Such findings would suggest that there is an association between age, obesity and fat pad thickness, whereby as a child's foot develops, the effects of obesity on fat pad thickness become more apparent and that fat pad thickness may increase with increasing body mass in obese children but remain stable in non-obese children. This notion is speculative and requires investigation. Furthermore, the functional relevance of a 0.5 mm difference in non-weight-bearing fat pad thickness is unknown.10 However, a previous study that quantified the thickness of tissues structures within the feet has claimed tissue thickness differences of 0.4 mm to be clinically relevant.20

Interestingly, even upon weight bearing, the between-subject group differences in fat pad thickness were still evident (mean difference of 0.3 mm) and the fat pad of the obese children compressed significantly more than did the fat pad of the non-obese participants. As the values for weight-bearing fat pad thickness were of similar size and difference to those seen during non-weight bearing, we speculate that fatty tissue in the midfoot region serves no functional purpose to the developing boney architecture. We therefore postulate that the additional fat padding evident in the midfoot in obese school-aged children is more a reflection of the children's excess adiposity rather than an adaptation to protect the development of the medial longitudinal arch.

Although previous studies have investigated internal arch height using radiography7, 21 and CT scans,22 no studies could be located that have used ultrasonography as a noninvasive and inexpensive measurement tool for medial longitudinal arch height in either children or adults. The only published radiographic investigation of children's feet was a study of older children during weight bearing in which the obese participants displayed a lower internal arch height than their non-obese counterparts.7 In this study, young obese children also displayed a significantly lower internal arch height relative to the non-obese children. This significant difference was still apparent when calculated as an index with truncated foot length (P<0.001). On the basis of these results, it appears that, due to the need to continually carry extra body mass, the medial longitudinal arches in the feet of obese young children remain lower than in the feet of lean children as these children get older. The functional relevance of these lower structural parameters and the resultant extent of damage to the developing feet of young obese children warrant investigation.

This is the first study to explore medial plantar fat pad thickness and internal plantar arch height in obese and non-obese school-aged children. The results highlight that obese children have significantly fatter and flatter feet compared to their leaner counterparts. However, the functional and clinical relevance of the increased fatness and flatness values in obese children remains unknown. Longitudinal research is therefore needed to ascertain the long-term effects of obesity on the structure of the medial longitudinal arch and to determine whether there are functional complications in the feet of obese individuals associated with their continual bearing of excess mass during childhood and beyond. Finally, there is a need for studies investigating the effects of obesity interventions in childhood on the structure and function of children's feet.

References

Bordin D, De Giorgi G, Mazzocco G, Rigon F . Flat and cavus foot, indexes of obesity and overweight in apopulation of primary-school children. Minerva Pediatr 2001; 53: 7–13.

Dowling AM, Steele JR, Baur LA . Does obesity influence foot structure and plantar pressure patterns in prepubescent children? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25: 845–852.

Mickle KJ, Steele JR, Munro BJ . The feet of overweight and obese young children: are they flat or fat? Obes Res 2006; 14: 1949–1953.

Riddiford-Harland DL, Steele JR, Storlien LH . Does obesity influence foot structure in prepubescent children? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000; 24: 541–544.

Welton EA . The Harris and Beath footprint: interpretations and clinical value. Foot Ankle 1992; 13: 462–468.

Mauch M, Grau S, Krauss I, Maiwald C, Horstmann T . Foot morphology of normal, underweight and overweight children. Int J Obes 2008; 32: 1068–1075.

Villarroya MA, Esquivel JM, Tomas C, Moreno LA, Buenafe A, Bueno G . Assessment of the medial longitudinal arch in children and adolescents with obesity: footprints and radiographic study. Eur J Pediatr 2009; 168: 559–567.

Tax HR . Podopediatrics, 4th ed. Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, 1985.

Volpon JB . Footprint analysis during the growth period. J Pediatr Orthop 1994; 14: 83–85.

Riddiford-Harland DL, Steele JR, Baur LA . Are the feet of obese children fat or flat? 14th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Australasian Society for the Study of Obesity; 28–30 October 2005; Glenelg, South Australia.

Jones RA, Okely AD, Collins CE, Morgan PJ, Steele JR, Warren JM et al. The HIKCUPS trial: a multi-site randomized controlled trial of a combined physical activity skill-development and dietary modification program in overweight and obese children. BMC Public Health 2007; 7: 15.

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH . Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000; 320: 1240–1243.

Parham K, Gordon C, Bensel C . Anthropometry of the Foot and Lower Leg of U.S. Army Soldiers: Fort Jackson, S.C. Army Natick Research, Development and Engineering Center: Natick, MA, 1992.

Riddiford-Harland DL, Steele JR, Baur LA . The use of ultrasound imaging to measure midfoot plantar fat pad thickness in children. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2007; 37: 644–647.

Hashimoto BE, Kramer DJ, Wiitala L . Applications of musculoskeletal sonography. J Clin Ultrasound 1999; 27: 293–318.

Vincent WJ . Statistics in Kinesiology. Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, 1995.

Timpson NJ, Sayers A, Davey-Smith G, Tobias JH . How does body fat influence bone mass in childhood? A Mendelian randomization approach. J Bone Min Res 2009; 24: 522–533.

Williams DS, McClay IS . Measurements used to characterize the foot and the medial longitudinal arch: Reliability and validity. Phys Ther 2000; 80: 864–871.

Queen RM, Mall NA, Hardaker WM, Nunley JA . Describing the medial longitudinal arch using footprint indices and a clinical grading system. Foot Ankle Int 2007; 28: 456–462.

Ozdemir H, Yilmaz E, Murat A, Karakurt L, Poyraz AK, Ogur E . Sonographic evaluation of plantar fasciitis and relation to body mass. Eur J Radiol 2005; 54: 443–447.

Saltzman CL, Nawoczenski DA, Talbot KD . Measurement of the medial longitudinal arch. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1995; 76: 45–49.

Ferri M, Scharfenberger AV, Goplen G, Daniels TR, Pearce D . Weightbearing CT scan of severe flexible pes planus deformities. Foot Ankle Int 2008; 29: 199–204.

Acknowledgements

We thank the research teams from the Hunter Illawarra Kids Challenge Using Parent Support (HIKCUPS) project, an Australian National Health & Medical Research Council funded project (354101), for their support during participant recruitment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Riddiford-Harland, D., Steele, J. & Baur, L. Are the feet of obese children fat or flat? Revisiting the debate. Int J Obes 35, 115–120 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.119

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.119

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Exploring flatfeet morphology in children aged 6–12 years: relationships with body mass and body height through footprints and three-dimensional measurements

European Journal of Pediatrics (2024)

-

Foot morphology as a predictor of hallux valgus development in children

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

The resting calcaneal stance position (RCSP): an old dog, with new tricks

European Journal of Pediatrics (2023)

-

Children’s foot parameters and basic anthropometry — do arch height and midfoot width change?

European Journal of Pediatrics (2022)

-

Foot loading patterns in normal weight, overweight and obese children aged 7 to 11 years

Journal of Foot and Ankle Research (2013)