Abstract

Background:

Adult Aboriginal Australians have 1.5-fold higher risk of obesity, but the trajectory of body mass index (BMI) through childhood and adolescence and the contribution of socio-economic factors remain unclear. Our objective was to determine the changes in BMI in Australian Aboriginal children relative to non-Aboriginal children as they move through adolescence into young adulthood, and to identify risk factors for higher BMI.

Methods:

A prospective cohort study of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal school children commenced in 2002 across 15 different screening areas across urban, regional and remote New South Wales, Australia. Socio-economic status was recorded at study enrolment and participants' BMI was measured every 2 years. We fitted a series of mixed linear regression models adjusting for age, birth weight and socio-economic status for boys and girls.

Results:

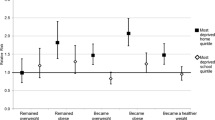

In all, 3418 (1949 Aboriginal) participants were screened over a total of 11 387 participant years of follow-up. The prevalence of obesity was higher among Aboriginal children from mean age 11 years at baseline (11.6 vs 7.6%) to 16 years at 8 years follow-up (18.6 vs 12.3%). The mean BMI increased with age and was significantly higher among Aboriginal girls compared with non-Aboriginal girls (P<0.01). Girls born of low birth weight had a lower BMI than girls born of normal birth weight (P<0.001). Socio-economic status and low birth weight had a differential effect on BMI for Aboriginal boys compared with non-Aboriginal boys (P for interaction=0.01). Aboriginal boys of highest socio-economic status, unlike those of lower socio-economic status, had a higher BMI compared with non-Aboriginal boys. Non-Aboriginal boys of low birth weight were heavier than Aboriginal boys.

Conclusions:

Socio-economic status and birth weight have differential effects on BMI among Aboriginal boys, and Aboriginal girls had a higher mean BMI than non-Aboriginal girls through childhood and adolescence. Intervention programs need to recognise the differential risk for obesity for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal boys and girls to maximise their impact.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380: 2224–2260.

Wang Y, Beydoun MA . The obesity epidemic in the United States—gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev 2007; 29: 6–28.

Miqueleiz E, Lostao L, Ortega P, Santos JM, Astasio P, Regidor E . Trends in the prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity according to socioeconomic status: Spain, 1987-2007. Eur J Clin Nutr 2014; 68: 209–214.

Shrewsbury V, Wardle J . Socioeconomic status and adiposity in childhood: a systematic review of cross-sectional studies 1990–2005. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008; 16: 275–284.

Due P, Damsgaard MT, Rasmussen M, Holstein BE, Wardle J, Merlo J et al. Socioeconomic position, macroeconomic environment and overweight among adolescents in 35 countries. Int J Obes 2009; 33: 1084–1093.

Australian Bureau of Statistics Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: First Results, Australia, 2012-13 Cat No. 4727055001. ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

Haysom L, Williams R, Hodson E, Lopez-Vargas P, Roy LP, Lyle D et al. Risk of CKD in Australian indigenous and nonindigenous children: a population-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 2009; 53: 229–237.

Haysom L, Williams R, Hodson E, Roy LP, Lyle D, Craig JC . Early chronic kidney disease in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australian children: remoteness, socioeconomic disadvantage or race? Kidney Int 2007; 71: 787–794.

Haysom L, Williams R, Hodson EM, Lopez-Vargas PA, Roy LP, Lyle DM et al. Natural history of chronic kidney disease in Australian Indigenous and non-Indigenous children: a 4-year population-based follow-up study. Med J Aust 2009; 190: 303–306.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare National best practice guidelines for collecting Indigenous status in health data sets Cat no IHW 29. AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2010.

Pan H, Cole TJ . LMSgrowth, a Microsoft Excel add-in to access growth references based on the LMS method. Version 2.77 2012 [cited 15 September 2012]. Available from http://www.healthforallchildren.com/?product=lmsgrowth.

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH . Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000; 320: 1240–1243.

Australian Bureau of Statistics Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas, Australia, 2001 Cat No. 20390. ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2001.

Australian Bureau of Statistics Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC) Cat No. 12160. ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2001.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Profiles of Health, Australia, 2011–2013 Cat No. 4338.0. ABS: Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

Spurrier NJ, Volkmer RE, Abdallah CA, Chong A . South Australian four-year-old Aboriginal children: residence and socioeconomic status influence weight. Aust NZ J Public Health 2012; 36: 285–290.

Gopinath B, Baur LA, Burlutsky G, Robaei D, Mitchell P . Socio-economic, familial and perinatal factors associated with obesity in Sydney schoolchildren. J Paediatr Child Health 2012; 48: 44–51.

Wake M, Hardy P, Canterford L, Sawyer M, Carlin JB . Overweight, obesity and girth of Australian preschoolers: prevalence and socio-economic correlates. Int J Obes 2007; 31: 1044–1051.

Hardy LL, O'Hara BJ, Hector D, Engelen L, Eades SJ . Temporal trends in weight and current weight-related behaviour of Australian Aboriginal school-aged children. Med J Aust 2014; 200: 667–671.

Australian Institute of Family Studies LSAC Annual Statistical Report 2012 2013; 1–184.

Boney CM, Verma A, Tucker R, Vohr BR . Metabolic syndrome in childhood: association with birth weight, maternal obesity, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics 2005; 115: e290–e296.

Reilly JJ, Armstrong J, Dorosty AR, Emmett PM, Ness A, Rogers I et al. Early life risk factors for obesity in childhood: cohort study. BMJ 2005; 330: 1357.

Aitsi-Selmi A, Batty GD, Barbieri MA, Silva AA, Cardoso VC, Goldani MZ et al. Childhood socioeconomic position, adult socioeconomic position and social mobility in relation to markers of adiposity in early adulthood: evidence of differential effects by gender in the 1978/79 Ribeirao Preto cohort study. Int J Obes 2013; 37: 439–447.

Wang Y, Zhang Q . Are American children and adolescents of low socioeconomic status at increased risk of obesity? Changes in the association between overweight and family income between 1971 and 2002. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 84: 707–716.

Kumanyika S . Ethnic minorities and weight control research priorities: where are we now and where do we need to be? Prev Med 2008; 47: 583–586.

Kumanyika SK . Special issues regarding obesity in minority populations. Ann Intern Med 1993; 119: 650–654.

Kumanyika SK . Environmental influences on childhood obesity: ethnic and cultural influences in context. Physiol Behav 2008; 94: 61–70.

Australian Bureau of Statistics Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Nutrition Results - Food and Nutrients, Australia Cat No. 4727055005, 2012-13. ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2014.

Australian Bureau of Statistics Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Physical activity, Australia Cat No. 4727055004, 2012-2013. ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2014.

Brimblecombe JK, O'Dea K . The role of energy cost in food choices for an Aboriginal population in northern Australia. Med J Aust 2009; 190: 549–551.

Burns CM, Inglis AD . Measuring food access in Melbourne: access to healthy and fast foods by car, bus and foot in an urban municipality in Melbourne. Health Place 2007; 13: 877–885.

Winkler E, Turrell G, Patterson C . Does living in a disadvantaged area entail limited opportunities to purchase fresh fruit and vegetables in terms of price, availability, and variety? Findings from the Brisbane Food Study. Health Place 2006; 12: 741–748.

Ball K, Timperio A, Crawford D . Neighbourhood socioeconomic inequalities in food access and affordability. Health Place 2009; 15: 578–585.

Winkler E, Turrell G, Patterson C . Does living in a disadvantaged area mean fewer opportunities to purchase fresh fruit and vegetables in the area? Findings from the Brisbane food study. Health Place 2006; 12: 306–319.

Black C, Moon G, Baird J . Dietary inequalities: what is the evidence for the effect of the neighbourhood food environment? Health Place 2014; 27: 229–242.

Brambilla P, Bedogni G, Heo M, Pietrobelli A . Waist circumference-to-height ratio predicts adiposity better than body mass index in children and adolescents. Int J Obes 2013; 37: 943–946.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and their communities, Aboriginal Medical Services and participating schools, for their support of the study since its inception in 2002. We also acknowledge the support of the ARDAC Advisory Committee in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplemental Appendix accompanies this paper on International Journal of Obesity website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S., Macaskill, P., Baur, L. et al. The differential effect of socio-economic status, birth weight and gender on body mass index in Australian Aboriginal Children. Int J Obes 40, 1089–1095 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.71

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.71