Abstract

Penicillenols (A1, A2, B1, B2, C1 and C2) were isolated from Aspergillus restrictus DFFSCS006, and could differentially inhibit biofilm formation and eradicate pre-developed biofilms of Candida albicans. Their structure–bioactivity relationships suggested that the saturation of hydrocarbon chain at C-8, R-configuration of C-5 and trans-configuration of the double bond between C-5 and C-6 of pyrrolidine-2,4-dione unit were important for their anti-biofilm activities. Penicillenols A2 and B1 slowed the hyphal growth and suppressed the transcripts of hypha specific genes HWP1, ALS1, ALS3, ECE1 and SAP4. Moreover, penicillenols A2 and B1 were found to act synergistically with amphotericin B against C. albicans biofilm formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Candida albicans is a harmless commensal together with other members of the microbiota in individuals with healthy immune systems, but when the system is impaired or the microbiota is changed, C. albicans is capable of causing life-threatening infections, often associated with the formation of biofilms.1 C. albicans biofilms, consisting of budding yeast, elongated hyphae and oval pseudohyphae, are inherently less sensitive to many clinical antifungal agents including fluconazole and amphotericin B and host immune defenses than planktonic cells.2, 3 Besides the C. albicans biofilm, the capacity of C. albicans to switch from yeast to hyphae is also associated with antifungal drug resistance, virulence, invasion and colonization, and the development of the spatially organized architecture of highly structured mature biofilms.4, 5 Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are capable of causing a series of acute and chronic infections, and biofilms protect them from antibiotics. Therefore, biofilms have shown to house a 100–1000-fold increase in tolerance towards antimicrobial agents compared with equivalent populations of their free-floating counterparts. Once biofilms colonized the indwelling medical devices, it became almost impossible to clear the infections.

In an attempt to find sources of anti-biofilm agents, many investigators have begun to extract and analyze natural products from plants and marine organisms.6 For example, -(-) epigallocatechin-3-gallate from tea and 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol from marine bacterium Vibrio alginolyticus G16 inhibited the biofilm formation of C. albicans.7, 8 In a preliminary experiment, the ethyl acetate extract of a culture broth of the deep-sea-derived fungus Aspergillus restrictus DFFSCS006 was found to exhibit significant antibacterial and anti-biofilm activity against Staphylococcus aureus and C. albicans. A further investigation on the chemical constituents of the extract led to the isolation of six penicillenols. Penicillenols A1, A2, B1, B2, C1 and C2 were first isolated from Penicillium sp. GQ-7 and marine-derived fungus Xylariaceae sp.9, 10 Penicillenols A1 and B1 exhibited cytotoxicity against HL-60 cell with IC50 values of 0.76 and 3.2 μm, respectively.9 Penicillenols B1 and B2 could inhibit the growth of S. aureus with MICs of 8 μm (2.2 μg ml−1) and 70 μm (19.4 μg ml−1), respectively.11 Penicillenols A1 and A2 did not show obvious activity against Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli at 50 μg per disk (6 mm).10 However, the anti-biofilm of the penicillenols discussed here has not been reported previously. In this study, penicillenols were obtained from a deep-sea-derived fungus A. restrictus DFFSCS006, and their anti-biofilm activities against S. aureus ATCC 6538, P. aeruginosa PAO1 and C. albicans SC5314, their structure–activity relationships and the mechanistic basis for penicillenols A2 and B1 mediating the inhibition of C. albicans biofilms were further studied.

Materials and methods

Strains

A. restrictus DFFSCS006 was isolated from a marine sediment sample collected from the South China Sea (17°59′742′ N, 111°48′092′ E, 2326 m depth)12 and grown on potato dextrose agar medium supplemented with 3% sea salt. S. aureus ATCC 6538 and P. aeruginosa PAO1 (ATCC 15692) were routinely cultivated at 37 and 30 °C, respectively, in Luria Bertani medium and C. albicans SC5314 was cultivated in yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) medium at 37 °C.

Fermentation, extraction, purification and identification

A. restrictus DFFSCS006 was inoculated in 120 ml soluble starch medium (10 g glucose per liter, 10 g starch soluble per liter, 1 g KH2PO4 per liter, 1 g MgSO4 per liter, 1 g pepton per liter and 30 g sea salt per liter) in a 500 ml flask and incubated on a rotary shaker (200 r.p.m.) at 28 °C for 2 days. Then each of 5 ml cultures was added into 300 ml liquid medium (20% potato, 2% maltose, 2% mannitol, 1% glucose, 0.5% monosodium glutamate, 0.5% peptone, 0.3% yeast and 3% sea salt, w/v) in a 1liter flask and incubated statically at 26 °C for 31 days.

After incubation, the fermentation broth was collected and filtered through cheesecloth to separate the supernatant and mycelia. The supernatant was mixed with XAD-16 resin and mycelia were extracted with 80% acetone. The resin and acetone extracts were evaporated and extracted with ethyl acetate to afford a 100 g brown crude gum.

The crude gum was chromatographed on a silica gel column eluting with various gradient concentrations of CHCl3/MeOH (100:0, 99:1, 98:2, 95:5, 90:10, 80:20 and 0:100, v/v) to obtain seven fractions. Fraction 4 (30 g) was subjected to MPLC (medium pressure preparative liquid chromatography) eluting with CHCl3/acetone (100:0, 90:10, 80:20, 70:30, 60:40 and 50:50, v/v) and CHCl3/MeOH (90:10, 80:20, 70:30 and 50:50, v/v) to give three sub-fractions (Fr.4-1~Fr.4-3). Fr.4-1 was further subjected to RP-MPLC (reversed-phase-MPLC) with an ODS column eluting with MeOH/H2O (from 20:80 to 0:100, 120 min, 20 ml min−1) to give four sub-fractions (Fr.4-1-1~Fr.4-4-4). Fr.4-1-1 was purified by sephedex LH-20 column eluting with CH3Cl-MeOH(1:1) and SP HPLC (semi-preparative high performance liquid chromatography; YMC-Pack, ODS-A S-5 μm × 12 nm 250 × 20 mm inner diameter, 5 ml min−1) eluting with MeOH-H2O-TFA (89:11:0.03) to get compounds penicillenol B1 (90.4 mg, tR=49.5 min) and penicillenol B2 (30.4 mg, tR=52.5 min). Fr.4-1-2 was purified by sephedex LH-20 column eluting with CH3Cl-MeOH (1:1) and then further purified by SP HPLC (YMC-Pack, ODS-A S-5 μm × 12 nm 250 × 20 mm inner diameter, 5 ml min−1) eluting with MeOH-H2O-TFA (74:26:0.03) to afford compounds penicillenol C2 (15.9 mg, tR=51.0 min) and penicillenol C1 (7.8 mg, tR=58.5 min). Fr.4-3 was also subjected to RP-MPLC with an ODS column eluting with MeOH/H2O (from 20:80 to 0:100, 120 min, 20 ml min−1) to give five sub-fractions (Fr.4-3-1~Fr.4-3-5). Fr.4-3-3 was purified by sephedex LH-20 column eluting with CH3Cl-MeOH (1:1) and then further purified by SP HPLC (YMC-Pack, ODS-A S-5 μm × 12 nm 250 × 20 mm inner diameter, 5 ml min−1) eluting with MeOH-H2O-TFA (76:24:0.03) to obtain compounds penicillenol A2 (21.0 mg, tR=51.8 min) and penicillenol A1 (22.1 mg, tR=45.0 min).

The 1H and 13C NMR data of penicillenols A1, A2, B1, B2, C1 and C2 were acquired with a Bruker AV-500 MHz NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Germany) with TMS as reference.

Determination of MICs

The MICs of penicillenols against C. albicans were tested by broth microdilution method in 96-well polystyrene plates (Corning, NY, USA) according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (2008).13 Wells containing 100 μl YPD with 2 × 106 cells ml−1 C. albicans were supplemented with various concentrations (3.12 to 200 μg ml−1) of six penicillenols separately and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. For S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, wells with 100 μl S. aureus/P. aeruginosa dilutions (OD600=0.01) were supplemented with different concentrations of the six penicillenols (3.12 to 200 μg ml−1) separately and incubated for 24 h. After incubation, optical densities at 600 nm (OD600) of the wells was measured using a Multiskan GO Reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Biofilm formation and destruction assay

The effects of penicillenols on the formation of C. albicans biofilms were assayed in the pre-sterilized polystyrene flat-bottomed 96-well plates (Corning, NY, USA).8, 14 Briefly, wells containing 150 μl mineral medium (0.7 g KH2PO4 per liter, 0.3 g K2HPO4 per liter, 0.5 g MgSO4 per liter, 2 g NaNO3 per liter, 0.5 g KCl per liter, 0.01 g FeSO4 per liter, pH 7) with 106 cells were subjected to different concentrations of penicillenols (6.25 to 200 μg ml−1) and then incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. After incubation, planktonic cells were discarded, and the wells were washed three times with sterile distilled water, dried, stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Shanghai Chemical Reagents Co. Ltd, China) for 30 min and dissolved with 30% acetic acid. OD570 was determined using a Multiskan GO Reader (Thermo Scientific). Biofilm inhibition was calculated using the following formula: Percentage biofilm inhibition=[(Control OD570−Treated OD570)/Control OD570] × 100. The biofilms of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa were also measured according to the above procedures with the initial OD600 of 0.01 and 24 h incubation. All the experiments were performed in eight replicates.

Moreover, the effects on biofilm disruption were detected with the biofilms grown in 96-well plates for 48 h as described above. The biofilms were treated with 12.5, 25, 50 and 100 μg ml−1 penicillenols, separately, for 48 h, and then stained with crystal violet.

Effects of penicillenols on hyphal growth

Hyphal growth assay was performed in 5 ml of YPD medium and YPD medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA). A total 2 × 107 cells ml−1 C. albicans in medium were incubated with different concentrations of penicillenols (25 and 50 μg ml−1) at 37 °C with agitation (200 r.p.m.). After 5 h, aliquots of samples were observed under bright field using × 40 objective lens by optical microscope and photographed.

Meanwhile, the effects of penicillenols on colony morphology were measured on YPD agar plates and YPD agar plates with 0.1 and 0.2 g Congo red per liter (Sigma, USA), respectively. One microliter cell suspension (106 cells ml−1) was spotted at the center of the agar plates supplemented with/without 30 μg ml−1 penicillenols, incubated at 37 °C for 48 and 96 h and then photographed.

RNA isolation and quantitative reverse transcription PCR

The cells grown in YPD supplemented with/without 25 μg ml−1 penicillenols with agitation for 5 h were collected, and the total RNAs were extracted using RNAiso Plus Reagent (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). The complementary DNA was synthesized with PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa) and 10-fold dilutions were used as templates to analyze the transcriptional levels of five hypha specific genes via quantitative reverse transcription PCR with paired primers and housekeeping internal control (ACT1; Table 1) as an internal standard with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa). The relative transcription level of each gene was evaluated as the ratio of its transcript in YPD with penicillenols over that in YPD medium with DMSO using the 2−ΔΔCt method.15

Extracellular polymeric substance inhibition and phospholipase production

Extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) inhibition was evaluated by the carbohydrate estimation method.8 Biofilms grown on glass side (1 × 1) in mineral medium with/without penicillenols (25 and 50 μg ml−1) were transferred into a glass tube separately, and 500 μl of 0.9% NaCl, 500 μl of 5% phenol and 2.5 ml of 0.2% (w/v) hydrazine sulfate in concentrated H2SO4 were added, and the tubes were incubated in dark for 1 h. Absorbance at OD490 was recorded using a Multiskan GO Reader (Thermo Scientific). EPS inhibition was calculated using the following formula: % EPS inhibition=[(Control OD490−Treated OD490)/Control OD490] × 100.

For phospholipase production, 1 μl cell suspension (106 cells ml−1) was placed at the middle of the phospholipase agar medium (1% peptone, 3% glucose, 5.73% NaCl, 0.055% CaCl2, 10% egg yolk emulsion and 1.8% agar, w/v) supplemented with/without 25 μg m−1 penicillenols and incubated at 37 °C for 96 h.8 Diameters of the colonies and the opaque precipitation zones around it were read and the formula: Phospholipase activity=Diameter of the colony/(Diameter of the colony+the precipitation zone) was used to analyze the phospholipase activity (Pz). Pz=1 means negative phospholipase activity, Pz=0.64–0.99 shows positive phospholipase activity and Pz⩽0.63 means very strong activity.16

Combination testing of penicillenols with amphotericin B on C. albicans biofilm formation

The synergistic effects of penicillenols with amphotericin B (AmB) were studied at their sub-BIC80 concentrations. Biofilm formation was initiated in the presence of the combination of each penicillenol (1.5 and 3.0 μg ml−1) and AmB (0.05 and 0.1 μg ml−1) or single compound in 96-well plates and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h as described above. The absorbance at 570 nm was determined using a Multiskan GO Reader (Thermo Scientific). All the experiments were performed in six replicates.

Data analysis

The results from eight replicates were expressed as mean±standard deviation (s.d.) and statistical analysis was subjected to one-factor analysis of variance performed with the Data Processing System software.17 It is considered to be statistically significant when *P<0.05 in all the experiments.

Results and Discussion

Penicillenols showed antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activity against S. aureus and C. albicans

Penicillenols (A1, A2, B1, B2, C1 and C2) were extracted and purified from the deep-sea-derived fungus A. restrictus DFFSCS006, and their structures (Figure 1a) were identified by comparison of their NMR data with reported data.9, 10 Previous studies reported that the six penicillenols showed cytotoxic activities against several cell lines, and penicillenols B1 and B2 also showed dose-dependent antimicrobial activity against S. aureus.9, 11 Their anti-biofilm activities have not been reported. Here, initial studies were conducted to determine the antimicrobial activities of penicillenols in vitro. The results (Table 2) showed that the penicillenols inhibited differentially the growth of S. aureus, and the MICs of penicillenols A2 and B1 are close to that of the antibiotic chloramphenicol, whereas all the penicillenols exhibited weak inhibition of C. albicans and P. aeruginosa with MICs >200 μg ml−1. Meanwhile, the anti-biofilm activities of penicillenols were investigated in 96-well microtiter plates. The BIC80 was defined to be the lowest concentration where the biofilm formation was inhibited by 80% as compared with control. We found that six penicillenols could inhibit the biofilm formation of C. albicans and S. aureus in varying degrees, where penicillenol A2 has the lowest BIC80 estimate, followed by penicillenol B1, penicillenol A1, penicillenol B2, penicillenol C2 and penicillenol C1 in turn (Table 2). For S. aureus, BIC80 estimates were greater than or equal to their MICs, which indicated that the anti-biofilm activity were due to the inhibition of S. aureus growth. For C. albicans, BIC80 estimate was 50 μg ml−1 for penicillenol A2, 100 μg ml−1 for penicillenol B1, 200 μg ml−1 for penicillenol A1, B2 and C2, and >200 μg ml−1 for penicillenol C1, respectively, which were lower than their MICs. However, all the penicillenols showed a BIC80 >200 μg ml−1 against P. aeruginosa (Table 2). These data indicated that penicillenols could inhibit the growth of S. aureus and the biofilm formation of C. albicans at the sub-MIC concentrations, but did not significantly affect the cell growth and biofilm formation of P. aeruginosa, which promoted us to choose C. albicans as the tested strain in the following experiments.

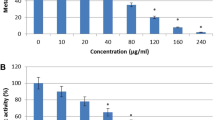

Penicillenols inhibited the C. albicans biofilm formation and eradicated the developed biofilms. (a) The chemical structures of six penicillenols. (b) The relative inhibitory rate of biofilm formation after treatment with penicillenols was quantified compared with the treatment without any penicillenol after 48 h in 96-well plates. (c) Crystal violet staining of biofilms treated with penicillenols A2 and B1 (0–50 μg ml−1). (d) The effects of six penicillenols on the 48 h grown biofilms were assayed in 96-well plates. Error bar: s.d. A full color version of this figure is available at The Journal of Antibiotics journal online.

Penicillenols inhibit biofilm formation and eradicate the preformed biofilm in C. albicans

Penicillenols inhibited the C. albicans biofilm formation in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 1b and c). At 100 μg ml−1, their inhibitory rates were up to 50% except penicillenol C1, and at 50 μg ml−1, the inhibitory rate was 81% for penicillenol A2, 75% for penicillenol B1, 58% for penicillenol C2, 54% for penicillenol B1 and 38% for penicillenol A1, respectively (Figure 1b). Furthermore, the susceptibilities of penicillenols against preformed biofilms were tested in 96-well microtiter plates with biofilms grown for 48 h. Figure 1d showed that penicillenols A2 and B1 could accelerate the eradication by up to 50% (62–68%) at 100 μg ml−1, whereas other penicillenols showed no obvious effect on the eradication of the developed biofilms. Meanwhile, the inhibitory rate of penicillenol A2 was a little higher than that of penicillenol B1. These data demonstrated that penicillenols A2 and B1 were more active than other four penicillenols.

Comparison of the structure–bioactivity of the penicillenols evaluated suggested that the saturated hydrocarbon chain at C-8 and trans-configuration of the double bond between C-5 and C-6 might significantly affect their anti-biofilm activities against C. albicans, which is consistent with the previous results that the presence of a saturated fatty chain at C-8 might be essential for the pharmacophore and penicillenol B1 (trans-configuration) was more active than penicillenol B2 in inhibiting the growth of S. aureus.11, 12 Meanwhile, the R-configuration of C-5 of pyrrolidine-2,4-dione unit was also implicated to be important for the anti-biofilm activity, which is different from the study where the S-configuration might be essential for anti-cancer activity.9

Penicillenols inhibit C. albicans hyphal growth

Hyphae participate in the biofilm formation and mediate the dissemination of C. albicans to the host tissues by invasion.18 Figure 2a showed that after 5 h, massive hyphae were observed in control samples without any penicillenol, however, hyphal growth was modest in 25 μg ml−1 penicillenol A2 and 50 μg ml−1 penicillenol B1, while hyphae were shortest in 50 μg ml−1 penicillenol A2 in both media, indicating the dose-dependent inhibition of hyphal growth by penicillenol A2 and penicillenol B1. Nevertheless, the growth of hyphae in YPD medium with FBS was slightly better than those in YPD medium (Figure 2a). These results indicated two penicillenols inhibited the hyphal growth, which might be a potential explanation for their inhibition of the biofilm formation in C. albicans.

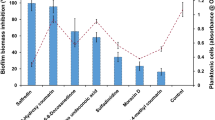

Effects of penicillenols A2 and B1 on C. albicans hyphal growth. (a) C. albicans cells were grown in YPD medium (upper) and YPD with 10% FBS (lower) at the indicated concentration of penicillenols A2 and B1 for 5 h with agitation. Each sample was photographed at × 40 magnification. (b) The relative transcriptional levels of hyphal specific genes in the presence of 25 μg ml−1 penicillenols A2 and B1 with respect to those in the absence of penicillenols A2 and B1 were displayed after normalization with internal control housekeeping gene ACT1. Error bar: s.d. FBS, fetal bovine serum; YPD, yeast peptone dextrose. The asterisked bar (*) in each three-bar group differs significantly from those unmarked (P<0.05).

To further investigate the potential mechanism of penicillenols A2 and B1 on the inhibition of C. albicans hyphal growth, we analyzed the transcripts of important genes associated with hyphal growth, including hyphal wall protein 1 (HWP1), agglutinin-like sequence 1 and 3 (ALS1 and ALS3), extent of cell elongation 1 (ECE1) and secreted aspartyl protease 4 (SAP4), in YPD medium and YPD medium supplemented with 25 μg ml−1 penicillenol A2 or B1, respectively. Compared with the transcripts in untreated cells, transcripts of HWP1, ALS1, ALS3, ECE1 and SAP4 were suppressed by 92%, 80%, 51%, 94% and 76% in penicillenol A2-treated cells, respectively, and 24%, 48%, 46%, 33% and 27% in penicillenol B1-treated cells, respectively (Figure 2b). It is reported that mutants of HWP1, ALS1 and/or ALS3 showed a defect in biofilm formation of C. albicans.19, 20, 21 Thus, the downregulation of these genes and the inhibition of hyphal growth mediated by penicillenols A2 and B1 could be a reason for the inhibition of C. albicans biofilm formation.

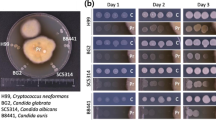

Meanwhile, penicillenols A2 and B1 reduced the growth of C. albicans colonies on the plates containing Congo red, a cell wall-disrupting agent interfering with the construction and stress response of the cell wall.22 As shown in Figure 3a, there was no obvious difference among all the colonies in YPD agar plates, whereas both penicillenol A2 and penicillenol B1 weakened the growth of C.albicans colonies in YPD agar plates with 0.1 and 0.2 mg ml−1 Congo red after incubation for 48 h (Figure 3a) and 96 h (Figure 3b), which suggested that the two penicillenols might cause a defective cell wall, which is important for fitness and virulence.20

Effects of 30 μg ml−1 penicillenols A2 and B1 on the C. albicans colonies growth in the YPD agar medium and YPD with Congo red (CR) agar medium after being grown for 48 h (a) and 96 h (b). A2, medium with 30 μg ml−1 penicillenols A2; B1:, medium with 30 μg ml−1 penicillenols B1; CN, control treatment without penicillenols A2 and B1; YPD, yeast peptone dextrose. A full color version of this figure is available at The Journal of Antibiotics journal online.

Effects of penicillenols A2 and B1 on EPS and phospholipase production and their synergistic effects with AmB on C. albicans biofilm formation

The EPS molecules, a major factor influencing the microbial biofilm formation process, were inhibited by 44% and 31% at 50 μg ml−1 penicillenols A2 and B1, respectively, and less than 10% by both 25 μg ml−1 penicillenols A2 and B1 (Figures 4a and b).

Effects of penicillenol A2 (a, c, e) and penicillenol B1 (b, d, f) on the EPS inhibition (a, b), phospholipase activity (c, d) and anti-biofilm activity after combined with AmB (e, f). CN, control treatment without penicillenols A2 and B1; EPS, extracellular polymeric substance. Error bar: s.d. The asterisked bar (*) in each three-bar group differs significantly from those unmarked (P<0.05).

Phospholipases, hydrolyzing enzymes vital for virulence, could cleave phospholipids in cell membranes, helping C. albicans invade host tissues. Phospholipase activity (Pz) testing showed that control C. albicans exhibited strong phospholipase activity, with a Pz of 0.54, which was reduced to 0.72 and 0.79 on treatment with penicillenols A2 and B1, respectively. The results demonstrated that penicillenols A2 and B1 reduced the phospholipase activity of C. albicans.

The activities of penicillenols A2 and B1 together with AmB against C. albicans biofilm formation were assayed in 96-well plates. The results showed that 1.5 and 3 μg ml−1 penicillenol A2, 1.5 and 3 μg ml−1 penicillenol B1, and 0.05 and 0.1 μg ml−1 AmB, inhibited the biofilm formation only by 11%, 19%, 9%, 13%, 15% and 21% respectively, but when 1.5 and 3 μg ml−1 penicillenol A2 were combined with 0.05 and 0.1 μg ml−1 AmB, respectively, the biofilm inhibitory rates were enhanced to 40%, 55%, 49% and 62%, respectively, which were higher than the sums of those of corresponding penicillenol A2 and AmB (Figure 4e). And the inhibitory rates were 50% for 1.5 μg ml−1 penicillenol B1 plus 0.1 μg ml−1 AmB, 36% for 3 μg ml−1 penicillenol B1 plus 0.05 μg ml−1 AmB and 56% for 3 μg ml−1 penicillenol B1 plus 0.1 μg ml−1 AmB, respectively, which were also higher than the sums of those of corresponding penicillenol B1 and AmB (Figure 4f). These data demonstrated that both penicillnols A2 and B1 might synergistically act with the antifungal agent AmB on C. albicans biofilm formation in varying degrees.

Conclusion

Penicillenols A2 and B1, isolated from the deep-sea-derived fungus A. restrictus DFFSCS006, inhibited the C. albicans biofilm formation by mediating the hyphal growth and the transcripts of related important genes including HWP1, ALS1, ALS3, ECE1 and SAP4. They also caused the inhibition of EPS and the decline of the phospholipase activity and could improve the anti-biofilm activity of AmB, implying a promising synergistic combination for the treatment of candidiasis. And the structure–activity relationship of penicillenols A1, A2, B1, B2, C1 and C2 revealed the saturated hydrocarbon chain at C-8, R-configuration of C-5 and trans-configuration of the double bond between C-5 and C-6 of pyrrolidine-2,4-dione unit might be important for their anti-biofilm activities against C. albicans.

References

D’Enfert, C. Hidden killers: persistence of opportunistic fungal pathogens in the human host. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12, 358–364 (2009).

Chandra, J. et al. Antifungal resistance of candidal biofilms formed on denture acrylic in vitro. J. Dent. Res. 80, 903–908 (2001).

Ramage, G., Saville, S. P., Thomas, D. P. & López-Ribot, J. L. Candida biofilms: an update. Eukaryot. Cell 4, 633–638 (2005).

Braga, P. C., Alfieri, M., Culici, M. & Dal Sasso, M. Inhibitory activity of thymol against the formation and viability of Candida albicans hyphae. Mycoses 50, 502–506 (2007).

Ha, K. C. & White, T. C. Effects of azole antifungal drugs on the transition from yeast cells to hyphae in susceptible and resistant isolates of the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agent Chemother. 43, 763–768 (1999).

Donia, M. & Hamann, M. T. Marine natural products and their potential applications as anti-infective agents. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3, 338–348 (2003).

Evensen, N. A. & Braun, P. C. The effects of tea polyphenols on Candida albicans: inhibition of biofilm formation and proteasome inactivation. Can. J. Microbiol. 55, 1033–1039 (2009).

Padmavathi, A. R., Bakkiyaraj, D., Thajuddin, N. & Pandian, S. K. Effect of 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol on growth and biofilm formation by an opportunistic fungus Candida albicans. Biofouling 31, 565–574 (2015).

Lin, Z. J. et al. Penicillenols from Penicillium sp. GQ-7, an endophytic fungus associated with Aegiceras corniculatum. Chem. Pharm. Bull 56, 217–221 (2008).

Nong, X. H., Zhang, X. Y., Xu, X. Y., Sun, Y. L. & Qi, S. H. Alkaloids from Xylariaceae sp., a marine-derived fungus. Nat. Prod. Commun. 9, 467–468 (2014).

Kempf, K., Schmitt, F., Bilitewski, U. & Schobert, R. Synthesis, stereochemical assignment, and bioactivity of the Penicillium metabolites penicillenols B1 and B2. Tetrahedron 71, 5064–5068 (2015).

Zhang, X. Y., Zhang, Y., Xu, X. Y. & Qi, S. H. Diverse deep-sea fungi from the South China Sea and their antimicrobial activity. Curr. Microbiol. 67, 525–530 (2013).

Haque, F., Alfatah, M., Ganesan, K. & Bhattacharyya, M. S. Inhibitory effect of sophorolipid on Candida albicans biofilm formation and hyphal growth. Sci. Rep. 6, 23575 (2016).

Villa, F. et al. Efficacy of zosteric acid sodium salt on the yeast biofilm model Canidida albicans. Microb. Ecol. 62, 584–598 (2011).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Price, M. F., Wilkinson, I. D. & Gentry, L. O. Plate method for detection of phospholipase activity in Candida albicans. Sabouraudia 20, 7–14 (1982).

Tang, Q. Y. & Feng, M. G. in DPS Data Processing System: Experimental Design, Statistical Analysis and Data Mining (eds Yan D. P., Zhao Y. C., Yang R.) 59–142 (Science Press, Beijing, (2007).

Sudbery, P. E. Growth of Candida albicans hyphae. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 737–748 (2011).

Nobile, C. J., Nett, J. E., Andes, D. R. & Mitchell, A. P. Function of Candida albicans adhesin Hwp1 in biofilm formation. Eukaryotic Cell 5, 1604–1610 (2006).

Klis, F. M., Sosinska, G. J., de Groot, P. W. J. & Brul, S. Covalently linked cell wall proteins of Candida albicans and their role in fitness and virulence. FEMS Yeast Res. 9, 1013–1028 (2009).

Zhao, X. et al. Candida albicans Als3p is required for wild-type biofilm formation on silicone elastomer surfaces. Microbiology 152, 2287–2299 (2006).

Ram, A. F. J. & Klis, F. M. Identification of fungal cell wall mutants using susceptibility assays based on Calcofluor white and Congo red. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2253–2256 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Strategic Leading Special Science and Technology Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA100304002), National Natural Science Foundation of China (41376160, 81673326, 31600060, and 41606100), National Marine Public Welfare Research Project of China (201305017), Regional Innovation Demonstration Project of Guangdong Province Marine Economic Development (GD2012-D01-002) and Guangzhou Science and Technology Research Projects (201607010305). We thank Professor Sang Jianli in Beijing Normal University for generously providing C. albicans SC5314.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Yao, QF., Amin, M. et al. Penicillenols from a deep-sea fungus Aspergillus restrictus inhibit Candida albicans biofilm formation and hyphal growth. J Antibiot 70, 763–770 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ja.2017.45

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ja.2017.45

This article is cited by

-

Phylogenetic analysis and antifouling potentials of culturable fungi in mangrove sediments from Techeng Isle, China

World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology (2018)