Abstract

The search for the earliest fossil evidence of the human lineage has been concentrated in East Africa. Here we report the discovery of six hominid specimens from Chad, central Africa, 2,500 km from the East African Rift Valley. The fossils include a nearly complete cranium and fragmentary lower jaws. The associated fauna suggest the fossils are between 6 and 7 million years old. The fossils display a unique mosaic of primitive and derived characters, and constitute a new genus and species of hominid. The distance from the Rift Valley, and the great antiquity of the fossils, suggest that the earliest members of the hominid clade were more widely distributed than has been thought, and that the divergence between the human and chimpanzee lineages was earlier than indicated by most molecular studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

From their initial description in 19251 until 1995, hominids from the Pliocene (5.3–1.6 million years, Myr) and late Upper Miocene (∼7.5–5.3 Myr) were known only from southern and eastern Africa. This distribution led some authors to postulate an East African origin for the hominid clade (where the term ‘hominid’ refers to any member of that group more closely related to extant humans than to the extant chimpanzee, Pan)2,3. The focus on East Africa has been especially strong in the past decade, with the description of several new forms from Kenya and Ethiopia, including Kenyanthropus platyops (3.5 Myr; ref. 4); Australopithecus anamensis (3.9–4.1 Myr; ref. 5); Ardipithecus ramidus ramidus (4.4 Myr; ref. 6); Ardipithecus ramidus kadabba (5.2–5.8 Myr; ref. 7) and Orrorin tugenensis (∼6 Myr; refs 8, 9). The discoveries of A. ramidus ramidus, A. r. kadabba and O. tugenensis have extended the human lineage well back into the Miocene. However, the discovery of Australopithecus bahrelghazali in Chad, central Africa10,11, demonstrated a considerably wider geographic range for early hominids than conventionally expected.

Since 2001, the Mission Paléoanthropologique Franco–Tchadienne (MPFT), a scientific collaboration between Poitiers University, Ndjamena University and Centre National d'Appui à la Recherche (CNAR) (Ndjaména), has recovered hominid specimens, including a nearly complete cranium, from a single locality (TM 266) in the Toros-Menalla fossiliferous area of the Djurab Desert of northern Chad (Table 1). The constitution of the associated fauna suggests that the fossils are older than material dated at 6 Myr from Lukeino, Kenya8,9. Preliminary comparison with the fauna from the Nawata formation at Lothagam, Kenya12,13, suggests that the fossils are from the Late Miocene, between 6 and 7 Myr old. All six recovered specimens are assigned to a new taxon that is, at present, the oldest known member of the hominid clade.

Systematic palaeontology

-

Order Primates L., 1758

-

Suborder Anthropoidea Mivart, 1864

-

Superfamily Hominoidea Gray, 1825

-

Family Hominidae Gray, 1825

-

Sahelanthropus gen. nov.

Etymology. The generic name refers to the Sahel, the region of Africa bordering the southern Sahara in which the fossils were found.

Generic description. Cranium (probably male) with an orthognathic face showing weak subnasal prognathism, a small ape-size braincase, a long and narrow basicranium, and characterized by the following morphology: the upper part of the face wide relative to a mediolaterally narrow and anteroposteriorly short lower face; a large canine fossa; a small and narrow U-shaped dental arch; orbits separated by a very wide interorbital pillar and crowned with a large, thick and continuous supraorbital torus; a flat frontal squama with no supratoral sulcus but with a marked postorbital constriction; a small, posteriorly located sagittal crest and a large nuchal crest (at least, in presumed males); a flat and relatively long nuchal plane with a large external occipital crest; a large mastoid process; small occipital condyles; a short, anteriorly narrow basioccipital; the long axis of the petrous temporal bone oriented roughly 30° relative to the sagittal plane; the biporion line touching the basion; a round external auditory porus; a broad glenoid cavity with a large postglenoid process; a robust and superoinferiorly short mandibular corpus associated with a wide extramolar sulcus; a large, anteriorly opening mental foramen centred beneath lower teeth P4–M1, below midcorpus height; relatively small incisors; distinct marginal ridges and multiple tubercles on the lingual fossa of upper I1; small (presumed male) upper canines longer mesiodistally than buccolingually; upper and lower canines with extensive apical wear; no lower c–P3 diastema; upper and lower premolars with two roots; molars with low rounded cusps and bulbous lingual faces, M3 triangular and M3 rounded distally; enamel thickness of cheek teeth intermediate between Pan and Australopithecus.

Differential diagnosis. Sahelanthropus is distinct from all living great apes in the following respects: relatively smaller canines with apical wear, the lower showing a full occlusion above the well-developed distal tubercle, probably correlated with a non-honing C–P3 complex (P3 still unknown).

Sahelanthropus is distinguished as a hominid from large living and known fossil hominoid genera in the following respects: from Pongo by a non-concave lateral facial profile, a wider interorbital pillar, superoinferiorly short subnasal height, an anteroposteriorly short face, robust supraorbital morphology, and many dental characters (described below); from Gorilla by smaller size, a narrower and less prognathic lower face, no supratoral sulcus, and smaller canines and lower-cusped cheek teeth; from Pan by an anteroposteriorly shorter face, a thicker and more continuous supraorbital torus with no supratoral sulcus, a relatively longer braincase and narrower basicranium with a flat nuchal plane and a large external occipital crest, and cheek teeth with thicker enamel; from Samburupithecus14 by a more anteriorly and higher-placed zygomatic process of the maxilla, smaller cheek teeth with lower cusps and without lingual cingula, and smaller upper premolars and M3; from Ouranopithecus15 by smaller size, a superoinferiorly, anteroposteriorly and mediolaterally shorter face, relatively thicker continuous supraorbital torus, markedly smaller but mesiodistally longer canines, apical wear and large distal tubercle in lower canines, and thinner postcanine enamel; from Sivapithecus16 by a superoinferiorly and anteroposteriorly shorter face with non-concave lateral profile, a wider interorbital pillar, smaller canines with apical wear, and thinner cheek-teeth enamel; from Dryopithecus17 by a less prognathic lower face with a wider interorbital pillar, larger supraorbital torus, and thicker postcanine enamel.

Sahelanthropus is also distinct from all known hominid genera in the following respects: from Homo by a small endocranial capacity (preliminary estimated range 320–380 cm3) associated with a long flat nuchal plane, a longer truncated triangle-shaped basioccipital, a flat frontal squama behind a robust continuous and undivided supraorbital torus, a large central upper incisor, and non-incisiform canines; from Paranthropus18 by a convex facial profile that is less mediolaterally wide with a much smaller malar region, no frontal trigone, the frontal squama with no hollow posterior to glabella, a smaller, longer and narrower braincase, the zygomatic process of the maxilla positioned more posterior relative to the tooth row, and markedly smaller cheek teeth; from Australopithecus19,20,21 by a less prognathic lower face (nasospinale–prosthion length shorter at least in presumed males) with a smaller malar (infraorbital) region and a larger, more continuous supraorbital torus, a relatively more elongate braincase, a relatively long, flat nuchal plane with a large external occipital crest, non-incisiform and mesiodistally long canines, and thinner cheek-teeth enamel; from Kenyanthropus4 by a narrower, more convex face, and a narrower braincase with more marked postorbital constriction and a larger nuchal crest; from Ardipithecus6,7 by upper I1 with distinctive lingual topography characterized by extensive development of the crests and cingulum; less incisiform upper canines not diamond shaped with a low distal shoulder and a mesiodistal long axis, bucco-lingually narrower lower canines with stronger distal tubercle, and P4 with two roots; from Orrorin8 by upper I1 with multiple tubercles on the lingual fossa, and non-chimp-like upper canines with extensive apical wear.

Type species. Sahelanthropus tchadensis sp. nov.

Etymology. In recognition that all specimens were recovered in Chad.

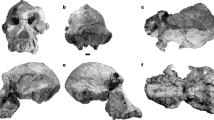

Holotype. TM 266-01-060-1, a nearly complete cranium with the following: on the right—I2 alveolus, C (distal part), P3–P4 roots, fragmentary M1 and M2, M3; and on the left—I2 alveolus, C–P4 roots, fragmentary M1–M3 (Fig. 1 and Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5). Found by D.A. on 19 July 2001.

After study, the holotype and paratype series will be housed in the Département de Conservation des Collections, Centre National d'Appui à la Recherche (CNAR) in Ndjaména, Chad. The holotype has been dubbed ‘Toumaï’; in the Goran language spoken in the Djurab Desert, this name is given to babies born just before the dry season, and means ‘hope of life’.

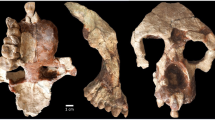

Paratypes. See Table 1 for a list of paratypes, and Fig. 2 for illustrations.

Locality. Toros-Menalla locality TM 266, a single quarry of about 5,000 m2, 16° 14′ 30″–16° 15′ 30″ N, 17° 28′ 30″–17° 30′ 00″ E (western Djurab Desert, northern Chad).

Horizon. All hominid specimens were found in the Toros-Menalla anthracotheriid unit (AU) and come from a perilacustrine sandstone12. The associated fauna is biochronologically12 older than fossils from Lukeino, Kenya (∼6 Myr; refs 8, 9), and more closely resembles material from the Nawata formation at Lothagam, Kenya, which is radio-isotopically dated to 5.2–7.4 Myr (ref. 13). Biochronological studies are still underway and TM 266 fauna can be tentatively dated between 6 and 7 Myr (ref. 12).

Diagnosis. Same as for genus.

Preservation

All specimens are relatively well preserved, but almost the entire cranium has been flattened dorsoventrally and the entire right side is depressed. The cranium exhibits broken but undistorted bone units and matrix-filled cracks (Fig. 1). Estimated measurements are given from a preliminary three-dimensional reconstruction. It will soon be possible to use computer tomography (CT) scans to generate a definitive three-dimensional reconstruction and stereolithographic casts.

Comparative observations

Cranial comparisons of comparably aged hominids are limited to a fragmentary basicranium and temporal bone: ARA-VP1/500 and ARA-VP1/125 (ref. 6) from 4.4 Myr Ardipithecus ramidus ramidus. The next-oldest maxillary and cranial specimens are younger: KNM-KP-29283 (A. anamensis5,20), KNM-WT40000 (Kenyanthropus platyops4), and A. afarensis specimens, which include the well-preserved AL 444-2 (ref. 21). The most notable anatomical features of the S. tchadensis cranium for comparative purposes are to be found in the face, which shows a mosaic of primitive and derived features. The face (Fig. 1a) is tall with a massive brow ridge, yet the mid-face is short (in the superoinferior dimension) and less prognathic than in Pan or Australopithecus (Table 3). This unusual combination of features is in turn associated with a relatively long braincase, comparable in size to those of extant apes (Fig. 1b, c). Preliminary comparisons with Pan suggest an endocranial volume of 320–380 cm3.

Although the Sahelanthropus cranium is considerably smaller than that of a modern male Gorilla, its supraorbital torus is relatively and absolutely thicker. This is probably a sexually dimorphic character (see Fig. 3), presumably reflecting strong sexual selection. If this is a male, then the combination of a massive brow ridge with small canines suggests that canine size was probably not strongly sexually dimorphic. The interorbital pillar is wide (Fig. 1a). The zygomatic process of the maxilla emerges above the mesial margin of M1 and is therefore more posterior relative to the cheek teeth than in Australopithecus19,20,21 and Paranthropus18. The infraorbital plane (from the lower orbital margin to the inferior malar margin) is similar to that of Pan and differs from both Gorilla and larger Australopithecus, in which this region is absolutely and relatively taller. The canine fossa is similar to that in AL 444-2 (ref. 21) and there is no diastema between the alveoli of I2 and C in the Chadian specimen. There is no supratoral sulcus. Between the temporal lines, the frontal squama is slightly depressed but not like the frontal trigone usually seen in P. boisei18. The temporal lines converge behind the coronal suture as in crested Pan, whereas their junction is more anterior than generally seen in some large A. afarensis (for example, AL 444-2; ref. 21). The sagittal crest is a little larger posteriorly than in either AL 444-2 (ref. 21) or KNM-WT 40000 (ref. 4). The compound temporal–nuchal crest is marked as in KNM-ER 1805 (ref. 22) and much larger than in the male A. afarensis AL 444-2 (ref. 21), suggesting a relatively large posterior temporalis muscle. The postorbital breadth (Fig. 1c) is absolutely smaller than the Pan–Gorilla average, and similar to that in AL 444-2 and AL 417-1 (ref. 21) (Table 5).

The basicranium (Fig. 1d) has small occipital condyles associated with an apparently large foramen magnum. Despite damage, the foramen magnum seems to be longer than wide, and not like the rounded shape typical of Pan. As in A. ramidus, the basion is intersected by the bicarotid chord; the basion is posterior in large apes and anterior in some of the later hominids. The Sahelanthropus basioccipital is correlatively short and shaped like a truncated triangle as in Ardipithecus6; it is not as triangular as in other early hominids.

Like Pan, Australopithecus21 and Ardipithecus6, the orientation of the petrous portion of the temporal is approximately 60° relative to the bicarotid chord, instead of 45° as is typical of Paranthropus and Homo. Unlike Gorilla, Pan and Ardipithecus6, the posterior margin of the tympanic tube does not have a crest-like morphology. Compared with known Ardipithecus (ARA-VP-1/500)6, the glenoid cavity is larger and the postglenoid process mediolaterally wider, so the pronounced squamotympanic fissure is situated more medially to the postglenoid process. The height of the relatively flat temporomandibular joint above the tooth row suggests a high ascending ramus of the mandible more similar in absolute size to Gorilla than to Pan. The large pneumatized mastoid process is anteroposteriorly long, more so than in Ardipithecus6 and Australopithecus (AL 444-2, AL 333)19,21. The flat nuchal plane is relatively longer (Fig. 1b, d and Table 4) than in Pan, Gorilla, AL 444-2 and AL 333, and with crests as marked as those of Gorilla, implying the presence of relatively large superficial neck muscles. The horizontally oriented nuchal plane is much flatter than the convex nuchal plane of Pan. There is not yet sufficient information to infer reliably whether Sahelanthropus was a habitual biped. However, such an inference would not be unreasonable given the skull's other basicranial and facial similarities to later fossil hominids that were clearly bipedal.

Little is preserved of the mandibular corpus in TM-266-02-154-1 or the symphysis in TM-266-01-060-2 to permit much discussion of mandibular anatomy. However, the former, presumably a male, has a thick corpus with a wide extramolar sulcus (Fig. 2a).

In dentition, both lower incisor roots are small. The lingual surface of upper I1 displays distinct marginal ridges converging basally onto a narrow gingival eminence and with several tubercles extending incisally into the lingual fossa (Fig. 2a). The smaller upper I2 alveolus is situated, in frontal view, lateral to the lateral edge of the nasal aperture (Fig. 1a), a probable symplesiomorphy with Pan. The upper and lower canines are small (Tables 1, 2). Given the absolutely and relatively massive supraorbital torus of the cranium (Figs 1a and 3), possibly reflecting strong sexual selection, and the thick corpus of the mandible (Fig. 2b, c), which probably indicate male status, we infer that Sahelanthropus canines were probably weakly sexually dimorphic. The upper canine (Fig. 1d) has both distal and apical wear facets whereas M3 is unworn. The lower canine (Fig. 2d, e) has a strong distal tubercle that is separated from a distolingual crest by a fovea-like groove; the large apical wear zone at a level above this distal tubercle implies a non-honing C–P3 complex (the P3 is still unknown). The upper canine, judging from the steep, narrow distal wear strip reaching basally, we believe had a somewhat lower distal shoulder than Ardipithecus6,7, suggesting an earlier evolutionary stage. Moreover, a small, elliptical contact facet for P3 on the distobuccal face of the distal tubercle indicates the absence of a lower c–P3 diastema. Sahelanthropus thus probably represents an early stage in the evolution of the non-honing C–P3 complex characteristic of the later hominids7.

The cheek teeth are small (Tables 1, 2), within the size range of A. ramidus and the lower end of A. afarensis. Lower c and the lower and upper premolars each have three pulp canals and two roots (Fig. 2c). The P3 has a 2R:MB + D pattern (terminology following ref. 22: R, root; M, mesial; MB, mesiobuccal; D, distal) with a small mesiobuccal root and two partially fused, larger oblique distal roots. The P4 has two transverse roots (2R:M + D), with the mesial one smaller than the distal; in both premolars the distal root has two pulp canals (Fig. 2c). The P4 teeth of Ardipithecus have more-derived root patterns, with either a Tome's root (A. r. kadabba)7 or a single root (A. r. ramidus)6. S. tchadensis has a P4 with a large talonid and well-marked grooves on the buccal face. The molar size gradient is M2 > M3 > M1. The upper molars have three roots, two buccal and one lingual, which is large and mesiodistally elongated. The M3 crowns are triangular whereas the M3 teeth are rectangular and rounded distally. The lower molar root pattern is 2R:M + D: a mesial root with two pulp canals and a distal root with only one canal (Fig. 2c).

The radial enamel thickness is 1.71 mm at paracone LM3 and 1.79 mm at hypocone LM2. The molar enamel is therefore thicker than in Pan, possibly thicker than in Ardipithecus ramidus ramidus, but thinner than in Australopithecus6. Given individual and intraspecific variation, further study using high-resolution imaging (CT scanning) is needed for useful comparisons7.

Discussion

Sahelanthropus has several derived hominid features, including small, apically worn canines—which indicate a probable non-honing C–P3 complex—and intermediate postcanine enamel thickness. Several aspects of the basicranium (length, horizontal orientation, anterior position of the foramen magnum) and face (markedly reduced subnasal prognathism with no canine diastema, large continuous supraorbital torus) are similar to later hominids including Kenyanthropus and Homo. All these anatomical features indicate that Sahelanthropus belongs to the hominid clade.

In many other respects, however, Sahelanthropus exhibits a suite of primitive features including small brain size, a truncated triangular basioccipital bone, and the petrous portion of the temporal bone oriented 60° to the bicarotid chord. The observed mosaic of primitive and derived characters evident in Sahelanthropus indicates its phylogenetic position as a hominid close to the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees. Given the biochronological age of Sahelanthropus, the divergence of the chimpanzee and human lineages must have occurred before 6 Myr, which is earlier than suggested by some authors23,24. It is not yet possible to discern phylogenetic relationships between Sahelanthropus and Upper Miocene hominoids outside the hominid clade. Ouranopithecus15 (about 2 Myr older) is substantially larger, with quadrate orbits, a very prognathic and wide lower face, large male canines with a long buccolingual axis, and cheek teeth with very thick enamel. Samburupithecus14 (about 2.5 Myr older) has a low, posteriorly positioned (above M2) zygomatic process of the maxilla, cheek teeth with high cusps (similar to Gorilla), lingual cingula, large premolars and a large M3.

Sahelanthropus is the oldest and most primitive known member of the hominid clade, close to the divergence of hominids and chimpanzees. Further analysis will be necessary to make reliable inferences about the phylogenetic position of Sahelanthropus relative to known hominids. One possibility is that Sahelanthropus is a sister group of more recent hominids, including Ardipithecus. For the moment, productive comparisons of Sahelanthropus with Orrorin are difficult because described craniodental material of the latter is fragmentary and no Sahelanthropus postcrania are available. However, we note that in Orrorin, the upper canine resembles that of a female chimpanzee. The discoveries of Sahelanthropus along with Ardipithecus6,7 and Orrorin8 indicate that early hominids in the late Miocene were geographically more widespread than previously thought.

Finally, we note that S. tchadensis, the most primitive hominid, is from Chad, 2,500 km west of the East African Rift Valley. This suggests that an exclusively East African origin of the hominid clade is unlikely to be correct (contrary to ref. 8). It will never be possible to know precisely where or when the first hominid species originated, but we do know that hominids had dispersed throughout the Sahel and East Africa10 by 6 Myr. The recent acquisitions of Late Miocene hominid remains from three localities, as well as functional, phylogenetic and palaeoenvironmental studies now underway, promise to illuminate the earliest chapter in human evolutionary history. Sahelanthropus will be central in this endeavour, but more surprises can be expected.

_____________________________________________

NEW to Nature.com this week: the Evolution and Ecology Subject Area. Easy access to all of Nature Publishing Group's resources in Evolution and Ecology . All the latest Evolution and Ecology news, research and review highlights regularly updated by NPG's expert editors.

References

Dart, R. A. Australopithecus africanus, the man-ape of South Africa. Nature 115, 195–199 (1925)

Kortlandt, A. New Perspectives on Ape and Human Evolution 9–100 (Stichting voor Psychobiologie, Amsterdam, 1972)

Coppens, Y. Le singe, l'Afrique et l'Homme (Fayard, Paris, 1983)

Leakey, M. G. et al. New hominin genus from eastern Africa shows diverse middle Pliocene lineages. Nature 410, 433–440 (2001)

Leakey, M. G., Feibel, C. S., McDougall, I. & Walker, A. C. New four-million-year-old hominid species from Kanapoi and Allia Bay, Kenya. Nature 376, 565–571 (1995)

White, T. D., Suwa, G. & Asfaw, B. Australopithecus ramidus, a new species of hominid from Aramis, Ethiopia. Nature 371, 306–312 (1994)

Haile-Selassie, Y. Late Miocene hominids from the Middle Awash, Ethiopia. Nature 412, 178–181 (2001)

Senut, B. et al. First hominid from the Miocene (Lukeino Formation, Kenya). C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 332, 137–144 (2001)

Deino, A. L., Tauxe, L., Monaghan, M. & Hill, A. 40Ar/39Ar geochronology and paleomagnetic stratigraphy of the Lukeino and lower Chemeron Formations at Tabarin and Kapcheberek, Tugen Hills, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 42, 117–140 (2002)

Brunet, M. et al. The first australopithecine 2500 kilometres west of the Rift Valley (Chad). Nature 378, 273–275 (1995)

Brunet, M. et al. Australopithecus bahrelghazali, une nouvelle espèce d'Hominidé ancien de la région de Koro Toro (Tchad). C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 322, 907–913 (1996)

Vignaud, P. et al. Geology and palaeontology of the Upper Miocene Toros-Menalla hominid locality, Chad. Nature 418, 152–155 (2002)

McDougall, I. & Feibel, C. S. Numerical age control for the Miocene–Pliocene succession at Lothagam, a hominoid-bearing sequence in the northern Kenya Rift. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 156, 731–745 (1999)

Ishida, H. & Pickford, M. A new Late Miocene hominoid from Kenya: Samburupithecus kiptalami gen. et sp. nov. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 325, 823–829 (1998)

Bonis, L. de & Koufos, G. D. The face and the mandible of Ouranopithecus macedoniensis: description of new specimens and comparisons. J. Hum. Evol. 24, 469–491 (1993)

Pilbeam, D. New hominoid skull material from the Miocene of Pakistan. Nature 295, 232–234 (1982)

Kordos, L. & Begun, D. R. A new cranium of Dryopithecus from Rudabanya, Hungary. J. Hum. Evol. 41, 689–700 (2001)

Tobias, P. V. The Cranium and Maxillary Dentition of Australopithecus (Zinjanthropus) boisei, Olduvai Gorge (Cambridge Univ. Press, London, 1967)

Kimbel, W. H., White, T. D. & Johanson, D. C. Cranial morphology of Australopithecus afarensis; A comparative study based on a composite reconstruction of the adult skull. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 64, 337–388 (1984)

Ward, C. V., Leakey, M. G. & Walker, A. Morphology of Australopithecus anamensis from Kanapoi and Allia Bay, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 41, 235–368 (2001)

Kimbel, W. H., Johanson, D. C. & Rak, Y. The first skull and other new discoveries of Australopithecus afarensis at Hadar, Ethiopia. Nature 368, 449–451 (1994)

Wood, B. Koobi Fora Research Project: Hominid Cranial Remains Vol. 4 (Clarendon, Oxford, 1991)

Kumar, S. & Hedges, B. A molecular time scale for vertebrate evolution. Nature 392, 917–920 (1998)

Pilbeam, D. in The Primate Fossil Record (ed. Hartwig, W.) 303–310 (Columbia Univ. Press, New York, 2002)

Kimbel, W. H. Systematic assessment of a maxilla of Homo from Hadar, Ethiopia. Am. J. Phys. Anthop. 103, 235–262 (1997)

Uchida, A. Intra-species Variation among the Great-Apes: Implications for Taxonomy of Fossil Hominoids Thesis, Harvard Univ. (1992)

Lockwood, C. A., Kimbel, W. H. & Johanson, D. C. Temporal trends and metric variation in the mandibles and dentition of A. afarensis. J. Hum. Evol. 39, 23–55 (2000)

Lockwood, C. A. Sexual dimorphism in the face of Australopithecus africanus. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 108, 97–127 (1999)

Acknowledgements

We thank the Chadian Authorities (Ministère de l'Education Nationale de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche, Université de N'djaména, CNAR). We extend gratitude for their support to the French Ministries, Ministère Français de l'Education Nationale (Faculté des Sciences, Université de Poitiers), Ministère de la Recherche (CNRS), Ministère des Affaires Etrangères (Direction de la Coopération Scientifique, Universitaire et de Recherche, Paris, and SCAC Ambassade de France à N'djaména), to the Région Poitou-Charentes, the Département de la Vienne, the Association pour le Prix scientifique Philip Morris, and also to the Armée Française (MAM and Epervier) for logistic support. For giving us the opportunity to work with their collections, we are grateful to the National Museum of Ethiopia, the National Museum of Kenya, the Peabody Museum and Harvard University, the Institute of Human Origins and the University of California. Special thanks to Scanner-IRM Poitou Charentes (P. Chartier and F. Perrin), for industrial scanner to EMPA (A. Flisch Ing. HTL) and to Multimedia Laboratorium-Computer Department, University of Zurich-Irchel (P. Stucki). Many thanks to all our colleagues and friends for their help and discussion, and particularly to F. Clark Howell, A. Garaudel, Y. Haile-Selassie, D. Johanson, W. Kimbel, M. G. Leakey, D. Lieberman, R. Macchiarelli, M. Pickford, B. Senut, G. Suwa, T. White and Lubaka. We especially thank all the other MPFT members who joined us for the field missions, and V. Bellefet, S. Riffaut and J.-C. Bertrand for technical support. We are most grateful to G. Florent for administrative guidance. We dedicate this article to J. D. Clark. All authors are members of the MPFT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brunet, M., Guy, F., Pilbeam, D. et al. A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa. Nature 418, 145–151 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature00879

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature00879

This article is cited by

-

Seven-million-year-old femur suggests ancient human relative walked upright

Nature (2022)

-

Enamel proteome shows that Gigantopithecus was an early diverging pongine

Nature (2019)

-

Using primate models to study the evolution of human locomotion: concepts and cases

BMSAP (2014)

-

The evolution of the upright posture and gait—a review and a new synthesis

Naturwissenschaften (2010)

-

Applications of X-ray synchrotron microtomography for non-destructive 3D studies of paleontological specimens

Applied Physics A (2006)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.