Abstract

The fossil record of the living great apes is poor. New fossils from undocumented areas, particularly the equatorial forested habitats of extant hominoids, are therefore crucial for understanding their origins and evolution1. Two main competing hypotheses have been proposed for orang-utan origins: dental similarities2,3 support an origin from Lufengpithecus, a South Chinese4 and Thai Middle Miocene hominoid2; facial and palatal similarities5 support an origin from Sivapithecus, a Miocene hominoid from the Siwaliks of Indo-Pakistan4,6. However, materials other than teeth and faces do not support these hypotheses7,8. Here we describe the lower jaw of a new hominoid from the Late Miocene of Thailand, Khoratpithecus piriyai gen. et sp. nov., which shares unique derived characters with orang-utans and supports a hypothesis of closer relationships with orang-utans than other known Miocene hominoids. It can therefore be considered as the closest known relative of orang-utans. Ancestors of this great ape were therefore evolving in Thailand under tropical conditions similar to those of today, in contrast with Southern China and Pakistan, where temperate9 or more seasonal10 climates appeared during the Late Miocene.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

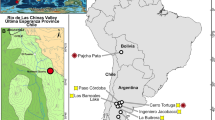

Khoratpithecus piriyai gen. et sp. nov. corresponds to undistorted mandibular corpora, lacking part of the left side inferiorly and also right and left rami, preserving roots of left canine–right I2 as well as the rest of the dentition. It originates from a sand pit in Chalerm Prakieat District, Nakorn Ratchasima Province (Khorat) of Northeastern Thailand (15° 01′ 35″ N, 102° 16′ 50″ E). Sediments correspond to large meandering channels with many tree trunks identified as cf. Corypha (palm), cf. Terminalia, cf. Parashorea and Dipterocarps (C. Vozenin-Serra, personal communication). Large mammals including proboscidians (Deinotherium indicum, Gomphotherium sp., Stegolophodon sp. and primitive Stegodon), anthracothere, pig (Hippopotamodon sivalensis), rhinos (Chilotherium palaeosinense, Brachypotherium perimense and Alicornops complanatum), bovids, giraffids (Sivatherium sp.) and rare hipparions are present. The faunal assemblage corresponds to Upper Nagri and Lower Dhok Pathan Formations of Siwaliks and indicates an early Late Miocene age, between 9 and 7 Myr (million years)11.

Systematics. Order Primates Linnaeus 1758; suborder Anthropoidea Mivart 1864; superfamily Hominoidea Gray 1825; family Hominidae Gray 1825; subfamily Ponginae Elliot 1913; Khoratpithecus gen. nov.

Type species. Khoratpithecus piriyai sp. nov.

Referred species. cf. Lufengpithecus chiangmuanensis Chaimanee et al. 2003, Middle Miocene of Thailand.

Etymology. Khoratpithecus means ape from Khorat.

Diagnosis. Large hominoid of the size of Lufengpithecus, with a high and very thick lower jaw corpus bearing a strong lateral eminence at M3 level, broad canine–incisor area, U-shaped dental arcade. Symphysis long and proclined with weak upper transverse torus, shallow posteriorly oriented genial fossa and strong inferior transverse torus. Absence of anterior digastric muscle impressions. Canine buccolingually compressed with flat lingual surface, distal groove and shallow lingual cingulum. Procumbent and large lateral incisor roots. Sectorial P3 without metaconid cusp. P4 with high talonid bearing strong cusps. M3 large with discontinuous buccal cingulid, buccally located hypoconulid and large distal fovea. Its original character association distinguishes it from other Miocene hominoids. Differs also from Lufengpithecus by its larger anterior dentition, canine structure and larger M3. From Gigantopithecus by its less distally extended symphysis, larger canine, sectorial P3, less elongated molars and less distally divergent tooth rows. From Ouranopithecus by its sectorial P3 and thinner enamel. From Pongo by its thicker symphysis with less distally elongated lower transverse torus, smaller incisor alveola, shorter P4, less peripheralized molar cusps, M3/M2 proportions, less wrinkled enamel and stronger lateral eminence.

Khoratpithecus piriyai sp. nov.

Etymology. In honour of Piriya Vachajitpan, who played a critical part in recovering the fossil.

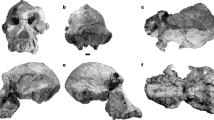

Holotype. Incomplete mandibular corpora, RIN 765 (Rajabhat Institute, Nakorn Ratchasima) (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Locality and age. Sand pit in Nakorn Ratchasima Province (Khorat), Northeastern Thailand, Late Miocene age.

Diagnosis. Differs from Khoratpithecus chiangmuanensis (Chaimanee et al. 2003) by its buccolingually compressed canine with flat lingual surface, larger lower incisors roots and enlarged M3.

Description. In occlusal view, the mandible displays a broad U-shaped dental arcade, widest at the level of canines and M3, with buccally concave tooth rows. Procumbent incisor roots are arranged on a slightly convex arcade and occupy a wide area (27 mm). Left canine section has a triangular outline with rounded corners. The right canine crown has a length/breadth ratio of 1.49, higher than in most other Miocene and extant apes excluding Dryopithecus and Ouranopithecus12. Its relative height index is 1.48, less than that of Kenyapithecus wickeri (1.62), Dryopithecus (1.54–1.61) and Lufengpithecus (1.56–1.85), falling into the range of Proconsul and great apes (1.42–1.58) (ref. 13). The short and weak anterior ridge curves lingually into the cingulid and the posterior ridge ends into a talonid cusp. A wide groove develops buccally to the distal ridge. Lingual wall is flattened, as in Griphopithecus14, and bears two furrows bounding a medial ridge. A shallow lingual cingulid is present above the enamel–dentine junction. Canines of K. chiangmuanensis and L. lufengensis display rounded/oval sections at the dentine–enamel junction and L. lufengensis has a stronger lingual cingulid. The canine of Sivapithecus is less outwardly oriented, with more rounded crown and stronger lingual cingulid15. K. piriyai canine resembles those of some Pleistocene Pongo16, sharing flat lingual walls, wide distal grooves and shallow lingual cingulids. Premolars and M1–M2 are similar to those of K. chiangmuanensis but molars differ from those of L. lufengensis by M2/M1 crown surface ratio (135% on K. piriyai and 172% on L. lufengensis). Regression of M1 dimensions on body mass in extant primates17,18,19 indicates a body weight of approximately 70–80 kg. M2 is broad, having a mesiodistal length/mesial width index of 108.5 (N = 2) that falls into the range of Sivapithecus20. M3 is very large, differing from Lufengpithecus by its M3/M1 crown surface ratio (196.5% for K. piriyai, 142% for male L. lufengensis, 128% for L. keiyuanensis) and bears a discontinuous buccal cingulid. Its central fovea is deep and displays enamel wrinkles. Talonid and distal fovea are large. It resembles Ouranopithecus by its buccal cingulid and on-line positioned buccal cusps. M3 of Gigantopithecus giganteus has shallow central fovea and more elongated outline. Inferiorly, the mandible displays a long and wide symphyseal region. Medially, facets for the geniohyoid muscles are well expressed. Laterally to them, the basal symphyseal surface displays no impression of muscle insertion that could correspond to the anterior digastric muscles7,21. Other Miocene hominoids display impressions of these muscles and their absence is considered as an exclusive specialization of extant Pongo, in relation to the development of laryngeal air sac7,21. Laterally, the corpus is deep, with thickness/height index of 55% at P4 and 87% at M3. Depth is nearly constant from symphysis to M3. Corpus shows a deep post-CP3 depression, and an extreme thickness with strong lateral eminence at the M3 level. The foramen mentale is located below mesio-buccal P3 root, in a low position. The symphysis is strongly proclined (Fig. 2). In mid-sagittal cross-section, its long axis forms an angle of 42° to the alveolar margin of P3–M3, which is less than in other Miocene hominoids except Equatorius and Kenyapithecus wickeri20. It falls in the range of extant large-bodied apes, but at the uppermost limit of adult Pongo20. Its morphology and forward inclination are similar to those of Griphopithecus14, whose symphysis extends further distally with a deeper genial fossa. Internally, there is a long planum alveolare sloping at about 35° on the alveolar plane to a weak superior transverse torus. A shallow genial fossa, oriented distally, lies below the superior transverse torus, above a thick, rounded, inferior transverse torus that projects until the level of M1 trigonid. The buccal symphyseal surface is wide and flat. The symphysis of Ankarapithecus12, Sivapithecus21, Gigantopithecus giganteus, Ouranopithecus22 and Lufengpithecus21 are more vertically oriented (Fig. 2). G. giganteus and Lufengpithecus have no strongly developed inferior transverse tori, and Sivapithecus displays tori of relatively equal prominence7,21. Equatorius displays a thicker symphysis section, with a stronger superior torus20. Pongo shows stronger superior transverse torus, thinner section and more distally extended lower torus21,23,24. However, some variants of extant orang-utan symphysis21 are similar to that of Khoratpithecus.

Several Miocene Asian hominoids have been proposed as potential ancestors of orang-utans. On the basis of its facial and palatal similarities5, Sivapithecus was considered as the best candidate. However, its lower jaw anatomy has been considered markedly dissimilar in all essential components to the Pongo mandible6,21. Lufengpithecus, from the Late Miocene of South China, displays greater tooth resemblances to Pongo than Sivapithecus4,25, but it has been excluded from Pongo ancestry because of its different face and periorbital region structures. It has been allocated, like Ankarapithecus26, to the sister taxon of the Ponginae + Homininae26 or to a primitive sister taxon of the Ponginae4,27. K. chiangmuanensis, from the Middle Miocene of Thailand2, shares similar premolar and molar characters and large incisor roots with K. piriyai. Therefore we refer the Middle Miocene Thai species to the same new genus. Both species nevertheless differ significantly enough to be distinguished at specific level. Ankarapithecus, Sivapithecus, Lufengpithecus and Gigantopithecus are united as members of the Pongo clade26,27. Khoratpithecus displays all characters that distinguish the members of that clade and an original character assemblage that occurs in none of the known Miocene hominoids, justifying its allocation to a new genus. Resemblance of Khoratpithecus premolars and molars to those of Lufengpithecus are interpreted as shared primitive characters of the orang-utan clade. Khoratpithecus jaw shares several derived characters with Pleistocene and extant orang-utans; among them, the absence of anterior digastric muscles represents an exclusive synapomorphy7,21 demonstrating that it corresponds to orang-utan's closest related fossil hominoid. Both Khoratpithecus species are found in association with tropical floras, indicating that extant apes were differentiating in areas where tropical conditions have prevailed from Middle to Late Miocene. In Southern China, Late Miocene Lufengpithecus4 are associated with a more temperate flora9. In Pakistan, Late Miocene Sivapithecus remains belong to mammal communities, indicating more open environments and increasing seasonality10,11. Further discoveries in yet undocumented tropical areas seem to be crucial to an understanding of the origins and evolution of both orang-utans and African great apes.

References

Pilbeam, D. R. Genetic and morphological records of the Hominoidea and hominid origins: A synthesis. Mol. Phylog. Evol. 5, 155–168 (1996)

Chaimanee, Y. et al. A new middle Miocene hominoid from Thailand and orangutan origins. Nature 422, 61–65 (2003)

Schwartz, J. H. in Function, Phylogeny, and Fossils: Miocene Hominoid Evolution and Adaptations (eds Begun, D. R., Ward, C. V. & Rose, M. D.) 363–388 (Plenum, New York, 1997)

Kelley, J. in The Primate Fossil Record (ed. Hartwig, W. C) 369–384 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002)

Pilbeam, D. New hominoid skull material from the Miocene of Pakistan. Nature 295, 232–234 (1982)

Ward, S. in Function, Phylogeny, and Fossils: Miocene Hominoid Evolution and Adaptations (eds Begun, D. R., Ward, C. V. & Rose, M. D.) 269–290 (Plenum, New York, 1997)

Brown, B. The mandibles of Sivapithecus. Thesis, Kent State Univ. Graduate Coll., Kent, Ohio (1989)

Pilbeam, D. R., Rose, M. D., Barry, J. C. & Shah, S. M. I. New Sivapithecus humeri from Pakistan and the relationship of Sivapithecus and Pongo. Nature 348, 237–239 (1990)

Badgley, C., Guoqin, Q., Wanyong, C. & Defen, H. Paleoecology of a Miocene, tropical, upland fauna: Lufeng, China. Natl Geogr. Res. 4, 178–195 (1988)

Morgan, M. E., Kingston, J. D. & Marino, B. D. Carbon isotopic evidence for the emergence of C4 plants in the Neogene from Pakistan and Kenya. Nature 367, 162–165 (1994)

Barry, J. C. et al. Faunal and environmental change in the Late Miocene Siwaliks of Northern Pakistan. Paleobiol. Mem. 3(28), 1–71 (2002)

Begun, D. R. & Güleç, E. Restoration of the type and palate of Ankarapithecus meteai: Taxonomic and phylogenetic implications. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 105, 279–314 (1998)

Ward, S., Brown, B., Hill, A., Kelley, J. & Downs, W. Equatorius: A new hominoid genus from the Middle Miocene of Kenya. Science 285, 1382–1386 (1999)

Alpagut, B., Andrews, P. & Martin, L. New hominoid specimens from the Middle Miocene site at Pasalar, Turkey. J. Hum. Evol. 19, 397–422 (1990)

Pilbeam, D., Rose, M. D., Badgley, C. & Lipschutz, B. Miocene hominoids from Pakistan. Postilla 181, 1–94 (1980)

Hooijer, D. A. Prehistoric teeth of man and of the orang-utan from Central Sumatra, with notes on the fossil orang-utan from Java and Southern China. Zool. Med. 29, 175–301 (1948)

Conroy, G. C. Problems of body-weight estimation in fossil primates. Int. J. Primatol. 8, 115–137 (1987)

Gingerich, P. D., Smith, H. S. & Rosenberg, K. Allometric scaling in the dentition of primates and prediction of body weight from tooth size in fossils. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 58, 81–100 (1982)

Legendre, S. Les communautés de mammifères du Paléogène (Éocène supérieur et Oligocène) d'Europe occidentale: structures, milieux et évolution. Münch. Geowiss. Abh. 16, 1–110 (1989)

McCrossin, M. L. & Benefit, B. R. Recently recovered Kenyapithecus mandible and its implications for great ape and human origins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 1962–1966 (1993)

Brown, B. in Function, Phylogeny, and Fossils: Miocene Hominoid Evolution and Adaptations (eds Begun, D. R., Ward, C. V. & Rose, M. D.) 153–171 (Plenum, New York, 1997)

de Bonis, L. & Melentis, J. Les primates hominoïdes du Vallésien de Macédoine (Grèce). Étude de la machoire inférieure. Géobios 10, 849–885 (1977)

Daegling, D. J. Shape variation in the mandibular symphysis of apes: an application of a median axis method. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 91, 505–516 (1993)

Daegling, D. J. & Jungers, W. L. Elliptical Fourier analysis of symphyseal shape in great ape mandibles. J. Hum. Evol. 39, 107–122 (2000)

Harrison, T., Ji, X. & Su, D. On the systematic status of the late Neogene hominoids from Yunnan Province. China. J. Hum. Evol. 43, 207–227 (2002)

Alpagut, B. et al. A new specimen of Ankarapithecus meteai from the Sinap Formation of central Anatolia. Nature 382, 349–351 (1996)

Begun, D. R. in The Primate Fossil Record (ed. Hartwig, W. C.) 339–368 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002)

Acknowledgements

We thank L. de Bonis and D. Pilbeam for comments, help, discussions and for providing documents and comparative materials; P.-O. Antoine for the identification of large mammals; C. Vozenin-Serra for the identification of fossil wood; and M. Ponce de Léon and C. Zollikofer for the CT-Scan sections. This work is supported by the Fyssen and Leakey foundations, the Department of Mineral Resources (Bangkok), the Thai-French TRF-CNRS Biodiversity Project (PICS Thaïlande) and the C.N.R.S. ‘Eclipse’ Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chaimanee, Y., Suteethorn, V., Jintasakul, P. et al. A new orang-utan relative from the Late Miocene of Thailand. Nature 427, 439–441 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02245

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02245

This article is cited by

-

A new large pantherine and a sabre-toothed cat (Mammalia, Carnivora, Felidae) from the late Miocene hominoid-bearing Khorat sand pits, Nakhon Ratchasima Province, northeastern Thailand

The Science of Nature (2023)

-

Evolutionary ecology of Miocene hominoid primates in Southeast Asia

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Clay mineralogy indicates a mildly warm and humid living environment for the Miocene hominoid from the Zhaotong Basin, Yunnan, China

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Biogeographic distribution and metric dental variation of fossil and living orangutans (Pongo spp.)

Primates (2016)

-

The significance of changes in body mass in human evolution

BMSAP (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.