Abstract

Molecular motors play critical roles in the formation of mitotic spindles, either through controlling the stability of individual microtubules, or by crosslinking and sliding microtubule arrays. Kinesin-8 motors are best known for their regulatory roles in controlling microtubule dynamics. They contain microtubule-destabilizing activities, and restrict spindle length in a wide variety of cell types and organisms. Here, we report an antiparallel microtubule-sliding activity of the budding yeast kinesin-8, Kip3. The in vivo importance of this sliding activity was established through the identification of complementary Kip3 mutants that separate the sliding activity and microtubule-destabilizing activity. In conjunction with Cin8, a kinesin-5 family member, the sliding activity of Kip3 promotes bipolar spindle assembly and the maintenance of genome stability. We propose a slide–disassemble model where the sliding and destabilizing activity of Kip3 balance during pre-anaphase. This facilitates normal spindle assembly. However, the destabilizing activity of Kip3 dominates in late anaphase, inhibiting spindle elongation and ultimately promoting spindle disassembly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

During cell division, the spindle apparatus drives the spatial separation of sister chromatids over a distance of up to tens of micrometres. Spindle length therefore influences the fidelity of chromosome segregation1,2. The functional and dynamic properties of mitotic spindles are also reflected by characteristic spindle lengths3. Gene deletion and RNA-mediated interference (RNAi)-based approaches in the past have successfully identified numerous factors that participate in spindle-length regulation. These include microtubule regulators that affect the nucleation and assembly of individual microtubules, force-generating motors that sort and align microtubules, and factors that maintain chromosome cohesion and the structure of kinetochores3,4,5,6. Cooperation and antagonism between different regulators have been revealed by combinatorial analysis of gene deletions or gene knockdowns7,8,9. However, even a single gene product can have complex, potentially counteracting roles in spindle-length control, which could be obscured in the analysis of simple gene deletions or knockdowns. For this reason, the functional heterogeneity of individual regulators and its relevance to spindle-length control are not well understood.

Here we combine in vitro assays with genetic analysis to define counterbalancing activities of a conserved regulator of spindle length, the budding yeast kinesin-8 motor, Kip3. Our analysis illustrates the importance of considering this level of complexity for understanding sophisticated cellular machineries such as the mitotic spindle. Kinesin-8 motors, best known as microtubule-destabilizing factors10,11,12,13,14,15, restrict metaphase spindle length in a variety of organisms and cell types12,16,17,18,19. However, Kip3 seems to be an exception because kip3Δ cells do not exhibit altered pre-anaphase (metaphase-like) spindle length20. This is surprising because Kip3 clearly regulates the length of individual microtubules during pre-anaphase10,20,21. In contrast, Kip3 restricts spindle length at the end of anaphase when spindles fully extend22. Thus, the impact of Kip3 on the spindle varies during mitosis in a way that is not simply predicted by its known biochemical properties. As we recently characterized a non-motor microtubule-binding activity in the Kip3 tail domain21, we considered the possibility that Kip3 slides antiparallel microtubules, an activity that could potentially increase spindle length and counterbalance its activity in shortening spindles by promoting microtubule disassembly.

RESULTS

Kip3 slides apart antiparallel microtubules

A fluorescence microscopy-based assay was used to determine whether Kip3 crosslinks and slides microtubules. Recombinant Kip3 and a tail-truncation mutant (Kip3ΔT-LZ) were purified from yeast21 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S1). Kip3 or Kip3ΔT-LZ was pre-bound to track microtubules (green) that were immobilized on a coverslip. Cargo microtubules (red) were then flowed into the assay chamber. We used Taxol-GMPCPP double-stabilized cargo microtubules in these experiments to prevent the Kip3-mediated microtubule depolymerization23. We found that full-length Kip3 induced the alignment of cargo microtubules with track microtubules but Kip3ΔT-LZ did not (Fig. 1b). Nevertheless, Kip3 and Kip3ΔT-LZ bound the track microtubules equivalently in this assay (Supplementary Fig. S2). Thus, Kip3 contains a microtubule-crosslinking activity that depends on its tail domain. This tail domain contains a secondary microtubule-binding site, in addition to the primary binding site on the motor domain21.

(a) Schematic of the constructs used in this study. Kip3 contains a head (red, also called the motor domain), followed by a short neck consisting of 4–5 coiled-coil heptads (blue), and a tail domain (orange). The leucine zipper (green) was added to maintain the dimeric state of the tail-less Kip3 (Kip3ΔT-LZ)21. Kip3-CC was made by replacing the native Kip3 neck with the leucine zipper. (b) Cargo microtubules (red, labelled with HiLyte 647) were aligned with track microtubules (green, labelled with HiLyte 488) in the presence of Kip3, but not in the presence of Kip3ΔT-LZ. Track microtubules were first immobilized on the coverslip. Kip3 or Kip3ΔT-LZ at 150 nM, cargo microtubules and a final reaction mix were sequentially flowed into the chamber. Taxol (20 μM) was included in the assay to prevent microtubule depolymerization by Kip3. In this assay, a wash was also applied after binding of the motors to the track microtubules, reducing nonspecific adherence of motors to coverslips. Scale bar, 5 μm. (c) Kymographs show the localization of Kip3 during sliding or tug-of-war movements. Kip3 was labelled with tetramethylrhodamine and cargo microtubules were labelled with HiLyte 647. Input: 150 nM Kip3. Scale bars, 2 μm (horizontal) and 2 min (vertical). (d) Microtubules in a parallel orientation exhibit tug-of-war movement in the presence of 150 nM Kip3. Polarity-labelled microtubules (bright red for the plus end of cargo microtubules and bright green for the plus end of track microtubules) show a parallel orientation. + and − mark the microtubule plus end and minus end, respectively. Scale bar, 5 μm. Kymographs at the bottom show tug-of-war movement of cargo microtubules, with the numbers corresponding to those in the images above. Scale bars, 2 μm (horizontal) and 2 min (vertical). (e) Antiparallel microtubule sliding by Kip3. The same figure settings and experimental conditions as in d. (f) Kip3 slides cargo microtubules (arrows) along track microtubules with a similar velocity to that with which Kip3 glides cargo microtubules (arrowhead) on coverslips. Left, most cargo microtubules (red) were aligned with track microtubules (green) in the presence of 150 nM Kip3. Unaligned cargo microtubules were occasionally observed, which was captured by those Kip3s that nonspecifically attached to coverslips. Scale bar, 5 μm. Right, quantification of microtubule velocity with an initial input of 150 nM Kip3. Shown are mean±s.e.m. (n = 50 microtubules).

Time-lapse imaging revealed that Kip3 drives two types of movement of cargo microtubules along track microtubules: sliding and tug-of-war (Supplementary Videos S1 and S2). In either case, we often observed an accumulation of Kip3 on one end of cargo microtubules (Fig. 1c). This accumulation probably, although not exclusively, resulted from motors that walked along cargo microtubules and accumulated at the plus ends. Although Kip3 was pre-bound to track microtubules before initiating this sliding assay, Kip3 could detach from the track microtubule during the assay, rebind to cargo microtubules, and then walk to their plus ends.

Experiments with polarity-marked microtubules revealed a correlation between sliding and microtubule orientation. When the cargo and track microtubules were in a parallel orientation, Kip3 primarily induced tug-of-war movements (Fig. 1d). This is expected if multiple motors bind parallel microtubules with opposite orientations: some Kip3 molecules with the motor domain on the track microtubule, transporting the cargo in one direction, and some Kip3 molecules with the motor domain on the cargo microtubules mediating transport in the opposite direction. In this circumstance, the forces will not always be balanced, and some persistent sliding movements were, as expected, observed, but at a low frequency (Supplementary Figs S3 and S4). In contrast, Kip3 always induced sliding when the microtubules were in an antiparallel orientation, with the microtubule minus end as the leading end (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Figs S3 and S4). This is consistent with the well-characterized plus-end-directed motility of Kip3 (refs 10, 11). Moreover, although most cargo microtubules were aligned with track microtubules, occasionally we also found unaligned cargo microtubules (white arrowheads in Fig. 1f) resulting from nonspecific attachment of Kip3 to the coverslip, as occurs in standard microtubule gliding assays. We measured the gliding velocity of the unaligned microtubules and found that it is similar to the sliding velocity of aligned cargo microtubules (Fig. 1f). This suggests a model that when Kip3 is sliding microtubules, the motor domain of dimeric Kip3 moves along one microtubule and the tail domain remains in mostly static contact with the other microtubule. This is similar to dimeric kinesin-14s (refs 24, 25) but contrasts with tetrameric kinesin-5s. Kinesin-5s slide antiparallel microtubules at twice the velocity that they mediate gliding of unaligned microtubules. This is because of the bipolar tetrameric structure of kinesin-5s that enables their motor domains to walk simultaneously on the track and cargo microtubules26,27. In summary, we have identified an antiparallel microtubule-sliding activity of kinesin-8/Kip3 that could potentially promote spindle assembly and increase the length of mitotic spindles.

Kip3-mediated sliding of dynamic microtubules

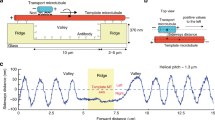

In addition to the above-described sliding of chemically stabilized microtubules, we found that Kip3 promotes antiparallel sliding of dynamic microtubules. This was established using recently developed methods using micropatterning technology to control the geometry of microtubule seeds, from which dynamic microtubules were polymerized28. In this assay, dynamic microtubules were polymerized with plus ends growing away from micropatterned sites positioned with 20 μm spacing (Fig. 2a). In the presence of Kip3, microtubules growing from adjacent micropatterned sites formed bundles that subsequently underwent buckling, which was not observed under control conditions (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Videos S3 and S4). As the microtubule seeds were adsorbed on the micropatterned sites, Kip3-dependent sliding was manifested as buckling of microtubule bundles. The degree of buckling was quantified by measuring the deflection of the bundle away from the axis connecting the two asters 30 min after the initiation of microtubule polymerization (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. S5).

(a) Schematic of the method for micropatterned microtubule growth. Polyethyleneglycol (PEG)-coated glass was placed under a photomask. The exposed spots, spaced by 20 μm, were made competent for the adsorption of microtubule seeds by deep-ultraviolet-induced oxidation of PEG. Tubulin was added to allow polymerization of dynamic microtubules from the seeds. (b) Time-lapse imaging showing curved microtubule bundles induced by Kip3. Dynamic microtubules (green) were growing from seeds (red) adsorbed on micropatterned sites in the presence of 10 μM of tubulin together with the indicated proteins (50 nM of Kip3, 33 nM of Ase1). White arrows indicate curved microtubule bundles in the presence of Kip3. Scale bar, 10 μm. (c) Quantification of the microtubule bundle deflection as an indicator of microtubule sliding. Left, schematic of the quantification. Right, Kip3 significantly increases the deflection of bundles. (n = 41, 40, 190 and 324 microtubule bundles for control, Kip3, Ase1 and Kip3+Ase1, respectively.)

To more faithfully mimic the organization of spindle microtubules, we determined whether Kip3 is able to induce sliding of antiparallel microtubules bundled by Ase1, the conserved microtubule-binding protein that organizes the spindle midzone29,30. As expected, Ase1 increased the frequency of antiparallel microtubule bundles from 16% to 60% and most of the bundles formed in the presence of Ase1 were straight (Fig. 2b,c and Supplementary Video S5). Strikingly, when both Kip3 and Ase1 were added together, stable microtubule bundles were formed that steadily elongated and underwent marked buckling (Fig. 2b,c and Supplementary Video S6). Whereas curved bundles were transiently slid in the presence of Kip3 (Supplementary Video S4), the collaboration between Ase1 and Kip3 led to the formation of stable bundles in which microtubule sliding persisted, leading to greater curvatures (Supplementary Video S6). Together, these data demonstrate that Kip3 mediates antiparallel sliding of its natural substrate: dynamic microtubules crosslinked by Ase1. This supports the conclusion that Kip3 has the ability to promote spindle assembly and increase spindle length.

Identification of a depolymerizing-proficient but sliding-deficient variant of Kip3

Previous genetic and biochemical evidence supports the idea that Kip3 promotes the shortening of microtubules through its microtubule-depolymerizing activity10,11,14. The microtubule-depolymerizing activity is assayed on GMPCPP-stabilized microtubules and has been proposed to reflect the ability to remove the GTP cap on dynamic microtubules and trigger catastrophe. Whether kinesin-8s other than Kip3 are microtubule depolymerases, however, remains a subject of debate15. Other mechanisms, for example, slowing microtubule growth, have been proposed to explain how these kinesin-8 motors shorten microtubules13. To simplify, we will refer below either to the destabilizing activity or depolymerase activity of Kip3, acknowledging that the mechanisms for destabilizing dynamic microtubules by kinesin-8s remain under investigation.

In principle, the depolymerizing activity and sliding activity of Kip3 could have opposite effects on spindle-length control. Such opposing effects could have obscured a role for Kip3 in spindle assembly during previous analysis of kip3Δ strains. To address this issue, we searched for mutants that would separate these biochemical activities. A candidate mutant that would be deficient for sliding activity but proficient for depolymerization was already in hand. We previously showed that the Kip3 tail domain concentrates Kip3 on the microtubule plus end, and increases the depolymerase activity of Kip3 by approximately twofold21. This effect is significant because a tail-truncation mutant produces a near-null phenotype in cells. However, normal microtubule-destabilizing function can be restored by doubling the gene dosage of the tail-truncation mutant in vivo or by doubling the concentration of the tail-truncation mutants in vitro21. On the other hand, as shown in Fig. 1b, this tail-truncation construct is deficient for microtubule crosslinking and sliding. Thus, this tail-truncation Kip3 mutant is depolymerase proficient but sliding deficient.

Characterizing a sliding-proficient but depolymerizing-deficient variant of Kip3

A mutant that was proficient for microtubule sliding but deficient for microtubule-depolymerase activity came out of our analysis of amino-acid sequences specific to the kinesin-8 family. All kinesin motor families share high sequence homology in the motor domain (also called head). However, many kinesin families have identifiable family-specific features, one of which is a family-specific neck. Kinesin-8s are one of the kinesin families that seem to have a family-specific neck sequence31. The neck in kinesin-8s is located at the carboxy terminus of the motor domain and is predicted to form a coiled-coil that mediates dimerization of the motor. To determine whether the kinesin-8-specific neck has a role in depolymerase activity, we replaced the Kip3 neck with a leucine zipper motif that maintains the dimeric state of the motor (Supplementary Fig. S1). First, we verified that this Kip3 variant, hereafter referred to as Kip3-CC (Fig. 1a), maintains comparable sliding activity to that of Kip3 (Fig. 3a–c). However, Kip3-CC was markedly deficient in depolymerase activity (∼ 10% of the full-length protein, Fig. 3d). As Kip3 depolymerizes GMPCPP-stabilized microtubules in a length-dependent manner11, we selected GMPCPP microtubules with a defined range of lengths (3–5 μm) for quantifying depolymerization rates. Moreover, the effects of Kip3 and Kip3-CC on dynamic microtubules assembled in vitro were also analysed. Consistent with another report14, we found that Kip3 promoted microtubule catastrophe. In contrast, Kip3-CC failed to promote microtubule catastrophe, under conditions where the plus-end-directed fluxes of Kip3 and Kip3-CC were comparable (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. S6). Furthermore, Kip3-CC failed to promote the catastrophe of astral microtubules in yeasts, whereas Kip3 increased the catastrophe frequency (Supplementary Table S1). Together, these data suggest that Kip3-CC is deficient in promoting microtubule disassembly.

(a) Kip3-CC slides microtubules. Top, cargo microtubules (red) were aligned with track microtubules (green) in the presence of Kip3-CC. Bottom, a kymograph of a single track microtubule with one cargo showing a tug-of-war movement (left) and another cargo exhibiting sliding movement (right). Kip3-CC at 150 nM, cargo microtubules and a reaction mix were sequentially added. Scale bar, 5 μm (horizontal) and 2 min (vertical). (b) Kymographs show the localization of Kip3-CC during sliding or tug-of-war movements. Kip3-CC was labelled with tetramethylrhodamine and cargo microtubules were labelled with HiLyte 647. Input: 150 nM Kip3-CC. Scale bars, 2 μm (horizontal) and 2 min (vertical). (c) Quantification of sliding rates with an initial input of 150 nM Kip3 or Kip3-CC. Shown are mean±s.e.m. (n = 50 microtubules). (d) Kip3-CC is deficient for depolymerase activity. Top, kymographs from depolymerase assays using GMPCPP-stabilized microtubules as substrates. Protein input, 12 nM. Scale bars, 2 μm (horizontal) and 1 min (vertical). Bottom, quantification of the microtubule-depolymerization rates of Kip3 or Kip3-CC. As Kip3 depolymerizes microtubules in a length-dependent manner11, microtubules within a narrow range of lengths were chosen for quantification. Lengths in the range 3–5 μm were chosen to correspond to the range of microtubule lengths in budding yeast (mostly below 5 μm). Shown are mean±s.e.m. (n = 50 microtubules). (e) Kip3-CC is defective in promoting catastrophe of dynamic microtubules in vitro. Top, kymographs show the assembly of HiLyte 647-labelled dynamic microtubules. As Kip3-CC has a higher microtubule landing frequency than Kip3 in the presence of tubulin dimers, the protein input was adjusted (150 nM Kip3 versus 6 nM Kip3-CC) to achieve a nearly identical measured flux of Kip3 and Kip3-CC on microtubules (Supplementary Fig. S7). Scale bars, 5 μm (horizontal) and 1 min (vertical). Bottom, quantification of the catastrophe frequency in the assay described above. Shown are mean±error. (n = 164, 25 and 23 catastrophe events for Kip3, Kip3-CC and control, respectively.) Growth rate and shrinkage rate are shown in Supplementary Fig. S7c.

The reduced microtubule-destabilizing activity of Kip3-CC could be due to a defect in motility that causes a reduced flux of motors to the microtubule plus end. Alternatively, the reduced depolymerase activity could reflect an intrinsically reduced capacity of Kip3-CC in removing tubulin dimers from the plus end. To distinguish between these two mechanisms, Halo-tagged Kip3 and Kip3-CC were labelled with tetramethylrhodamine (TMR) and their motilities were characterized by single-molecule imaging (Fig. 4a). The velocity of Kip3-CC was not significantly different from that of Kip3. We did observe that the average run length of Kip3-CC is reduced by 54% relative to Kip3 (Fig. 4b); however, Kip3-CC is still a highly processive motor with an average run length exceeding 5 μm, longer than almost all microtubules in budding yeast. For microtubules of comparable length to those used to assay depolymerase activity (3–5 μm), equal concentrations of Kip3 and Kip3-CC gave, as expected, similar flux to the plus end (32 versus 31 min−1), but Kip3-CC was nevertheless markedly deficient for depolymerase activity (Fig. 3d). Thus, the substitution of the Kip3 neck with a leucine zipper motif results in a mutant that markedly reduces microtubule-destabilizing activity, but largely maintains motility and sliding activity.

(a) Kymographs from single-molecule imaging assay visualizing the motility of TMR-labelled Kip3 or Kip3-CC at ∼ 0.1 nM on Taxol-stabilized microtubules. An image of fluorescein-labelled microtubules was acquired separately to determine the position of microtubule ends, as indicated by the asterisks. Scale bars, 5 μm (horizontal) and 1 min (vertical). (b) Quantification of the motility and plus-end dwell time of Kip3 and Kip3-CC. Histograms show the distribution of velocity, run length and plus-end dwell time of the motors. The distribution of velocity was fitted to a Gaussian curve. The distributions of run length and plus-end dwell time were fitted to a first-order exponential curve. Shown are mean±s.e.m. (n = 250motors for velocity measurements. n = 150 motors for run length and plus-end dwell time measurements).

Spindle length is regulated by a balance between the microtubule-sliding and -destabilizing activity of Kip3

As a first step towards determining whether the sliding activity of Kip3 has a role in spindle-length control, we characterized the effects of overexpressing Kip3-CC in cells lacking the endogenous KIP3 gene. Overexpression of Kip3-CC using a pGAL1 expression system caused an apparent increase in spindle length in cycling cells (Fig. 5a). To exclude the possibility that this effect was merely due to altered cell-cycle progression, cells were synchronized in S phase by hydroxyurea. In this case, overexpression of Kip3-CC caused a ∼ 50% increase in spindle length relative to the control (Fig. 5b). This effect is highly significant and comparable to the overexpression of Cin8, the main kinesin-5 sliding motor in budding yeast8. Several experiments strengthen the conclusion that it is the sliding activity of Kip3-CC that causes the increase in spindle length (Fig. 5b). First, overexpressing Kip3ΔT-LZ, which lacks microtubule-sliding activity, did not increase spindle length. Second, although Kip3-CC overexpression increased spindle length, it did not affect astral microtubule length, suggesting that the increase in spindle length does not result simply from an increase in the length of individual microtubules. Third, a Kip3 rigor mutant32 that crosslinks microtubules but does not walk on or slide apart microtubules, did not cause an increase in spindle length, excluding an explanation for the increase in spindle length involving passive crosslinking of microtubules by Kip3 that would increase the sliding effectiveness of other outward-sliding motors. This type of mechanism was previously suggested to explain the role of kinesin-14/Kar3 in spindle-length control 33. Fourth, the localization of Ase1 to spindles was significantly reduced when Kip3-CC was overexpressed (Supplementary Fig. S7a and b). Ase1 (orthologue of human PRC1) is a spindle midzone protein that preferentially binds to antiparallel microtubules34. The reduced localization of Ase1 to spindles suggests a decrease in spindle microtubule overlap, supporting the conclusion that the increase in spindle length results from sliding driven by Kip3-CC. Finally, although we cannot completely exclude the possibility that Kip3-CC indirectly increases spindle length by cargo transport, the mid-spindle localization of Stu2, the only known Kip3 cargo35, was not measurably affected by overexpressing Kip3-CC (Supplementary Fig. S7c and d). Together, these data suggest that Kip3-CC increases spindle 1 length because of its microtubule-sliding activity.

(a) Fluorescent microscopy visualizing spindles in cycling cells overexpressing Kip3-CC. Green: spindle marked by Tub1–GFP; red: spindle pole body marked by SPC42–CFP, Blue: cell boundary obtained by bright-field images. Kip3-CC was overexpressed using a pGAL1 expression system. Scale bar, 5 μm. (b) Comparisons of spindle lengths and astral microtubule lengths among cells overexpressing the indicated constructs. These cells were synchronized in S phase by hydroxyurea. Shown are mean±s.e.m. (n = 50 cells). (c) Comparison of pre-anaphase spindle lengths in cells expressing kip3 mutants from the endogenous KIP3 promoter. Tub1–GFP was used as a tracer to visualize spindles. Shown are mean±s.e.m. (n = 50 cells). P values were obtained from a two-tailed Student t-test. (d) Effects of Kip3 mutants on late anaphase spindle length. Time-lapse imaging was performed to measure spindle length just before spindle disassembly. To exclude the effect from cell size on spindle length, we measured cell length on the long axis and verified that there were no significant differences among the size of four strains. Shown are mean±s.e.m. (n = 15 cells). P values were obtained from a two-tailed Student t-test. (e) Steady-state protein levels of EYFP-tagged Kip3 and variants. Shown is a western blot using an anti-GFP antibody. Tubulin serves as a loading control. (f) Localization of Kip3 and variants throughout the cell cycle. Images from fluorescence microscopy show cells expressing one copy of Kip3, one copy of Kip3-CC and two copies of Kip3ΔT-LZ. Kip3 and variants were labelled with EYFP. Microtubules were labelled with CFP–Tub1. Images of a single channel of Kip3 and variants are shown in the left panel. Merged images are shown in the right panel. Scale bar, 2 μm. (g) Quantification of accumulation of Kip3 and variants to pre-anaphase spindles. Shown are mean±s.e.m. (n = 50 spindles).

Next, we attempted to dissect the individual contributions of the sliding and depolymerizing activities of Kip3 to spindle-length control. The KIP3 locus was replaced with either kip3-CC (encoding a sliding-proficient but depolymerizing-deficient motor) or two copies of kip3ΔT-LZ (encoding a depolymerizing-proficient but sliding-deficient motor). As discussed above, 2x Kip3ΔT-LZ is comparable to Kip3 for its effects on microtubule depolymerization in vitro, and confers similar microtubule-destabilizing activity in vivo21. We found pre-anaphase spindle length was indistinguishable for wild-type and kip3Δ cells, consistent with previous reports20. In contrast, pre-anaphase spindles were longer in kip3-CC cells, but shorter in 2x kip3ΔT-LZ cells relative to the wild-type controls (Fig. 5c). By the end of anaphase, the spindles in kip3-CC cells hyper-elongated to an even greater degree than occurs in kip3Δ cells. 2x kip3ΔT-LZ cells exhibited a reciprocal effect where the spindles break down prematurely before separation of chromosomes at a spatial maximum (Fig. 5d). We verified that the steady-state protein level of Kip3-CC was indistinguishable from that of the wild-type protein, and that doubling of the gene dosage of kip3ΔT-LZ resulted in the approximate doubling of Kip3ΔT-LZ protein expression level (Fig. 5e). In addition, both Kip3-CC and 2x Kip3ΔT-LZ localized to pre-anaphase and anaphase spindles similarly to Kip3 (Fig. 5f,g), consistent with a direct effect of these proteins on spindle length. These data support the conclusion that the sliding activity of Kip3 increases spindle length whereas the depolymerizing activity of Kip3 decreases it. These two activities counteract each other to regulate spindle length.

The sliding activity of Kip3 promotes spindle assembly in combination with Cin8

In addition to its role in spindle-length control, genetic analysis suggested that the microtubule-sliding activity of Kip3, in combination with that of Cin8, makes an important contribution to bipolar spindle assembly. Individually, loss of Cin8 (cin8Δ) or the sliding activity of Kip3 (2x kip3ΔT-LZ) did not compromise bipolar spindle assembly. However, cin8Δ 2x kip3ΔT-LZ double mutants exhibited a marked defect in bipolar spindle assembly (Fig. 6a,b). In contrast, a synergistic defect in bipolar spindle assembly was not observed by combining 2x kip3ΔT-LZ with the deletion of the other kinesin-5 in budding yeast Kip1 (Fig. 6c,d). This is consistent with previous results suggesting that Kip1 plays a less important role than Cin8 in spindle assembly36. In addition, we noted the appearance of diploids or near-diploid aneuploids in the population of 2x kip3 Δ T-LZ cin8Δ haploid strains (Fig. 6e). The increase in ploidy is probably explained by the defects in bipolar spindle assembly leading to a failure of karyokinesis. This effect was robust to alteration of kip3ΔT-LZ gene dosage because diploids were also spontaneously generated in the population of kip3 Δ T-LZ cin8Δ haploid strains (Fig. 6e). Collectively these experiments establish that the sliding activity we report here for Kip3 makes physiologically important contributions to bipolar spindle assembly.

(a) Bipolar spindles were formed in large-budded cells from wild-type strains whereas the dot-like monopolar spindles were found in large-budded cells from 2x kip3ΔT-LZ cin8Δ strains. Spindles are labelled with GFP–Tub1. Scale bar, 5 μm. (b) Synergistic defects between 2x kip3ΔT-LZ and cin8Δ in forming bipolar spindles. Cells were arrested in the G1 phase by α-factor treatment and then released from the arrest. The percentage of cells with bipolar spindles was measured at the indicated time points after release. Two hundred cells were scored for each data point. (c) Images showing bipolar spindles formed in wild-type and 2x kip3ΔT-LZ kip1Δ strains. Spindles are labelled with GFP–Tub1. Scale bar, 5 μm. (d) 2x kip3ΔT-LZ and kip1Δ cells have a subtle defect in bipolar spindle assembly. Cells were arrested in the G1 phase by α-factor treatment, released, and the percentage of cells with bipolar spindles was quantified at the indicated time points. Two hundred cells were scored for each data point. (e) Significant increase in the ploidy of cells containing kip3ΔT-LZ cin8Δ double mutants. DNA content of the indicated strains was monitored by FACS sorting of propidium-iodide-stained cells. Note the 4N peak (arrows) appearing in 2x kip3ΔT-LZ cin8Δ cells and kip3ΔT-LZ cin8Δ cells, which indicates the presence of diploids in the population. (f) Overexpression of Kip3-CC partially rescues the spindle collapse of strains compromised for kinesin-5 function. cin8-3 kip1Δ cells were arrested in S phase by hydroxyurea at 24 °C. The expression of Kip3 variants was then induced. Aliquots of cells were either maintained at 24 °C or shifted to 37 °C to inactivate Cin8. Spc42–CFP and Tub1–GFP enabled the visualization of spindle pole bodies and spindles. Two hundred cells were scored for each condition. n = 3 independent experiments. Shown are mean±s.e.m. P values were obtained from a two-tailed Student t-test. (g) The sliding activity of Kip3 promotes spindle elongation in anaphase. Kip3-CC was expressed under endogenous KIP3 promoter. Time-lapse imaging was used to monitor spindle elongation in anaphase, which can be split into a fast phase (phase I) and a slow phase (phase II). Shown is mean±s.e.m. (n = 15 cells). #: P>0.05, *: 0.005<P<0.05, **: P<0.005. P values were obtained from a two-tailed Student t-test.

The two kinesin-5 proteins, Cin8 and Kip1, have been considered to be the major driving force for spindle assembly and spindle elongation in budding yeast. We therefore investigated whether the sliding activity of Kip3 could replace the role of these two kinesin-5s. Bipolar spindles fail to assemble when both Cin8 and Kip1 are functionally inactivated36. Overexpressing Kip3-CC did partially rescue spindle collapse in cells lacking functional kinesin-5s (Fig. 6f). The fact that this rescue is modest is probably due to the optimization of kinesin-5s for spindle assembly, in terms of both their bipolar tetrameric structure and the characteristics of their motor domains, as previously proposed on the basis of experiments using motor chimaeras in the Xenopus extract system37.

Spindle elongation in budding yeast has an initial fast elongation phase (anaphase I) followed by a slow elongation phase (anaphase II). Cells lacking Cin8 have slower phase I rates whereas cells lacking Kip1 have slower phase II rates38. Expression of Kip3-CC from the native KIP3 promoter increased the phase I spindle elongation rate of cin8Δ cells as well as the phase II spindle elongation rate of kip1Δ cells (Fig. 6g). Thus, the sliding activity of Kip3, if unopposed by its microtubule-destabilizing activity, can partially substitute for individual kinesin-5s to promote spindle elongation.

DISCUSSION

We propose a slide–disassemble model to describe how Kip3 promotes both spindle assembly early in mitosis and spindle disassembly during mitotic exit (Fig. 7). At the beginning of mitosis, Kip3 contributes to bipolar spindle assembly through its antiparallel microtubule-sliding activity. This is supported by genetic data showing that the sliding activity of either Kip3 or Cin8 is required for bipolar spindle assembly. Measurements of spindle lengths in cells expressing Kip3 mutants that are selectively defective for either sliding or depolymerizing suggest that these activities balance in a way that Kip3 has no net effect on spindle length in pre-anaphase. However, in late anaphase the balance shifts, favouring microtubule destabilization and spindle disassembly. This flip from a positive role in spindle assembly to triggering spindle disassembly may be explained by changes in the amount of microtubule overlap and changes in microtubule length that occur during anaphase. As anaphase proceeds, the mass of overlapping microtubules decreases, and correspondingly, the number of Kip3 molecules involved in microtubule sliding decreases. At the same time, the length of individual microtubules becomes longer during anaphase, resulting in strong accumulation of Kip3 on microtubule plus ends, further shifting the balance towards microtubule destabilization. The net effect would be for the destabilizing activity of Kip3 to dominate at the end of anaphase, promoting spindle disassembly.

Top, schematic illustrating how the microtubule sliding and destabilizing activity of Kip3 may affect spindle length individually and in an ensemble. In wild-type pre-anaphase cells, sliding and destabilizing activities seem to be in approximate balance, a conclusion that is supported by the absence of an alteration in pre-anaphase spindle length in cells completely lacking Kip3. Mutations that tip the balance in one direction or the other have corresponding effects on spindle length (long spindles in kip3-CC cells and shorter spindles in 2x kip3ΔT−LZ cells). Moreover, when the balance is tipped towards the destabilizing slide, as in 2x kip3ΔT-LZ cells, bipolar spindles fail to assemble if microtubule sliding is further diminished by loss of another antiparallel sliding motor Cin8. Bottom: on anaphase entry, the number of overlapping microtubules decreases and the degree of overlap for microtubule pairs eventually shrinks. At the same time, the length of interpolar microtubule increases by about fivefold, which is predicted to increase the amount of plus-end-associated Kip3 because of the remarkable processivity of Kip3. The increased amount of Kip3 will destabilize interpolar microtubules and eventually promote spindle disassembly.

The microtubule-sliding and -crosslinking activities of Kip3 are likely to be relevant to the function of kinesin-8s in other eukaryotic cell types. RNAi experiments showed that the human kinesin-8s Kif18A and Kif19 cooperate with kinesin-5/Eg5 to maintain spindle bipolarity in HeLa cells39. This could result from an underlying mechanism similar to Kip3 because the tail domain of Kif18A binds microtubules in vitro and associates with microtubules in cells40,41,42. In Drosophila spermatocytes, kinesin-8 Klp67A is likewise required to focus the central spindle during late anaphase43. This is plausibly explained by a putative microtubule-crosslinking activity of Klp67A because Klp67A also contains a secondary microtubule-binding tail44. We propose that the complex interplay between plus-end-directed motility, plus-end-destabilizing activity, microtubule crosslinking and microtubule sliding will be a general feature of kinesin-8 family motors. Other microtubule regulators, such as XMAP215, dynein and kinesin-14, may have similarly complex, context-dependent functions (reviewed in ref. 3). An accurate understanding of mitotic spindle function will ultimately require an understanding of the complexity of its individual components.

METHODS

Strains and coding sequences for recombinant proteins.

Supplementary Table S2 provides a list of yeast strains used in this study. Yeast strains were in the S288C background except those used for protein purification, which were in the W303-1A background. To fluorescently label the recombinant Kip3 variants, Halo tag (Promega), which enables covalent attachment of fluorescent dyes to proteins of interest in a 1:1 stoichiometry, was fused to the coding sequence of proteins through a GSSGSS linker.

Constructs and protein purification.

The coding sequences for the amino-terminal Halo-tagged full-length Kip3 (1–805), Kip3ΔT-LZ (Kip3 1–480+Gcn4 250–281) and Kip3-CC (Kip3 1–448+Gcn4 253–281+Kip3 478–805) were expressed from the GAL1 promoter on 2 μ plasmids (pRS425 backbone). A protease-deficient yeast strain was used for protein expression45. Protein expression was induced by addition of 2% galactose for 18 h at 30 °C before collecting cells. Cells were disrupted by mechanical force using a coffee grinder46. The yeast powder was thawed, and dissolved in cold lysis buffer containing 50 mM NaPO4, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM ATP-Mg, 40 mM imidazole, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche) and 2 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride at pH 7.4. Dounce homogenization was used to further lyse cells at 4 °C. After centrifugation at 180,000g for 45 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was collected and incubated with Ni2+ Sepharose (GE Healthcare) for 30 min at 4 °C. The beads were washed 3 times with a buffer containing 50 mM NaPO4, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1 mM ATP-Mg, 25 mM imidazole, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, protease inhibitor cocktail tablets and 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride at pH 7.4. The protein was labelled with 10 μM TMR (Promega) on beads for 1.5 h at 4 °C before elution of the proteins with stripping buffer (50 mM HEPES, 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 μM ATP-Mg and 0.1 mM dithiothreitol at pH 7.4). The protein elutes were adjusted to 250 mM NaCl and loaded onto a Uno S1 (Bio-rad) ion exchange column, which had been equilibrated with 50 mM HEPES, 250 mM NaCl and 50 μM ATP-Mg at pH 7.4. The protein was eluted by a linear gradient to 1 M NaCl over 15 column volumes. The elutes were supplemented with 10% sucrose and centrifuged at 200,000g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Chemical crosslinking.

Proteins around 1 μM were incubated with freshly prepared 1 mM ethylene glycol-bis(succinic acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester) (EGS, Sigma) at room temperature for 30 min in 50 mM HEPES, 400 mM NaCl, 50 μM ATP-Mg and 10% sucrose at pH 7.4. The reactions were quenched by adding 40 mM Tris-Cl and 50 mM glycine at pH 7.5 and incubating at room temperature for 30 min.

Preparing stabilized microtubules.

Tubulin was purified from bovine brain by two rounds of assembly and disassembly, followed by phosphocellulose chromatography. N-ethylmaleimide (NEM)-modified tubulin was prepared using the Mitchison Laboratory protocol (http://mitchison.med.harvard.edu/protocols/microtubules/PreparationofSegmentedandPolarityMarkedMicrotubules.pdf). Fluorescein-, rhodamine-, HiLyte 488-, HiLyte 647- and biotin-labelled tubulin were purchased from Cytoskeleton. To prepare Taxol-stabilized microtubules for motility assays, a tubulin stock (BRB80 (80 mM PIPES-K+, 1 mM EGTA and 1 mM MgCl2 at pH 6.8) containing 20 μM tubulin, 2 μM fluorescein-labelled tubulin, 2 μM biotin-labelled tubulin, 1 mM GTP-Mg, 1 mM dithiothreitol and 10% dimethylsulphoxide) was incubated at 37 °C for 45 min. Taxol was added to a concentration of 20 μM. The mix was then incubated at 37 °C for 3 h before use. To prepare GMPCPP-stabilized microtubules for the depolymerase assay, microtubule seeds were generated by incubating the seed mix (BRB80 containing 20 μM tubulin, 0.2 μM biotin–tubulin, 5 μM fluorescein–tubulin and 1 mM GMPCPP-Mg) at 37 °C for 30 min. The elongation mix was made by diluting the seed mix at a 1:10 ratio with BRB80+0.5 mM GMPCPP. The seed was added to the elongation mix at a 1:40 ratio after pre-warming the elongation mix at 37 °C for 1 min. The final mix was incubated for 3 h at 37 °C before use. To prepare track microtubules for the sliding assays, a tubulin seed stock (BRB80 (80 mM PIPES-K+, 1 mM EGTA and 1 mM MgCl2 at pH 6.8) containing 20 μM tubulin, 2 μM fluorescein- or HiLyte 488-tubulin, 2 μM biotin-labelled tubulin and 1 mM GTP-Mg) was thawed, supplemented with 10% dimethylsulphoxide, and incubated at 37 °C for 45 min. Taxol was added to a concentration of 20 μM. The mix was then incubated at 37 °C for 3 h or longer. An elongation mix stock (BRB80 containing 2 μM tubulin, 0.5 μM fluorescein-labelled tubulin, 0.02 μM biotin-labelled tubulin, 0.5 μM NEM-tubulin and 1 mM GMPCPP-Mg) was pre-warmed to 37 °C, and then added into the seed mix for 1 h incubation at 37 °C before ready to use. A similar procedure was adopted to prepare the short cargo microtubules, with the following modifications: fluorescein–tubulin was replaced with rhodamine–tubulin or HiLyte-647–tubulin; biotin–tubulin was omitted; GMPCPP was used in all reactions; the incubation time for the seed mix was shortened to 30 min.

Sliding assay on stabilized microtubules.

Assay chambers with a volume of approximately 10 μl were made by forming a coverslip/double-sided tape/glass slide sandwich. The buffer volume flowed into the chamber in each of the following steps was around 20 μl. The chambers were sequentially coated with 1 mg ml−1 biotin–BSA and 0.5 mg ml−1 streptavidin, allowing Taxol-stabilized track microtubules to be immobilized on the coverslips. The reaction pre-mixtures contained BRB80 buffer at pH 7.2 supplemented with 0.5 mg ml−1 casein, 5% glycerol, 20 μM Taxol and 50 mM KCl. Pre-mixtures supplemented with 0.5 mM AMP-PNP and 150 nM motors were flowed into the chamber, and then rhodamine-labelled cargo microtubules diluted in the pre-mixtures supplemented with 0.5 mM AMP-PNP were flowed into the chambers. AMP-PNP was used to enhance the frequency that cargo microtubules were captured by motors on track microtubules. Microtubule alignment and sliding were also observed with ATP but at a lower frequency. After cargo microtubules were captured by motors in the chamber, the chamber was washed with pre-mixtures supplemented with 0.5 mM AMP-PNP. The final reaction buffer contained the pre-mixtures supplemented with 2 mM ATP and oxygen scavenging mix (0.2 mg ml−1 glucose oxidase, 0.035 mg ml−1 catalase, 25 mM glucose and 70 mM β-mercaptoethanol). An image from the GFP channel was taken at the beginning of the experiment to locate the position of the track microtubules. Time-lapse images from the Cy3 channel were acquired every 15 s for 20 min to trace the movement of cargo microtubules. The images were captured using a Zeiss AX10 Imager M1 microscope equipped with a CoolSnap HQ camera (Roper Scientific) and a ×63 1.4 NA oil-immersion objective. The same microscope, camera and objective were used for all of the other imaging experiments except those involving total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. All of the images were captured at room temperature unless specified. Kymographs were generated to quantify the sliding speed, motor velocity, run length, end dwell time and depolymerase rate.

Sliding of dynamic microtubules growing from micropatterned seeds.

Detailed methods were previously described28. This protocol was followed except that the composition of the elongation mix was modified: 2 μM of Atto-488–tubulin, 8 μM of unlabelled tubulin in BRB80 supplemented with 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM GTP, 0.2% BSA, 0.025% methyl cellulose (1,500 CP), and an oxygen scavenger cocktail (2 mg ml−1 glucose, 80 μg ml−1 catalase and 0.67 mg ml−1 glucose oxidase). Dynamic microtubules were visualized using a ×60 objective-based azimuthal ilas2 TIRF microscope (Nikon eclipse Ti, modified by Roper scientific) equipped with an Evolve 512 camera (Photometrics). The microscope stage was maintained at 32 °C using a warm-stage controller (LINKAM MC60). Excitation was achieved using 491 nm and 561 nm lasers (Optical Insights) with an exposure time of 70 ms. Time-lapse recording (one frame every 5 s) was performed using Metamorph software (version.7.7.5, Universal Imaging). Movies were processed to improve the signal/noise ratio (equalize light, low-pass and flatten-background filters of Metamorph software). Static images were taken 30 min after the reactions were started to quantify the microtubule bundle deflections.

Motility assays.

Track microtubules were immobilized in the assay chamber as describedabove. Motor proteins were diluted to 50 pM in reaction mixtures containing BRB80 buffer at pH 7.2 supplemented with 0.5 mg ml−1 casein, 5% glycerol, 2 mM ATP-Mg, 20 μM Taxol, 50 mM KCl and oxygen scavenging mix (0.2 mg ml−1 glucose oxidase, 0.035 mg ml−1 catalase, 25 mM glucose and 70 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Images were recorded with 100 ms exposure every 2 s for 20 min, using an Olympus IX-81 TIRF microscope equipped with a back-thinned electron multiplier CCD (charge-coupled device) camera (Hamamatsu) and a ×100 1.45 NA oil-immersion TIRF objective.

Depolymerase assay.

Experimental conditions were similar to those for the motility assay, with the following modifications: GMPCPP-stabilized microtubules were used instead of Taxol-stabilized microtubules; Taxol was not included in the reaction mixtures; wide-field images were acquired every 15 s for 10 min; motor input was from 6 to 24 nM.

Dynamic microtubules assay.

Flow cells were made using double-sided tape with passivated coverslips containing PEG and PEG–biotin (2 mg ml−1 and 20 μg ml−1, respectively, Laysan Bio) as described in ref. 47. HiLyte 488-labelled GMPCPP seeds were immobilized to the coverslips as described in the motility assay. The tubulin growth mix (14 μM tubulin, 0.7 μM HiLyte 647-labelled tubulin, 1 mM GTP, 2 mM ATP-Mg, 1 mg ml−1 casein, 0.1% methyl cellulose and an oxygen scavenging system described in the motility assay) was then introduced into the chamber. Microtubules were allowed to grow for 5 min at room temperature before flowing in motors diluted in the same growth mix. Time-lapse imaging was recorded at room temperature with 100 ms exposure every 0.5 s for 10 min. Image analysis was performed as previously described in ref. 14. Pauses were included in the calculation of growth rates.

Cellular imaging and data analysis.

Yeast strains were grown to log phase in SC media at 30 °C before imaging. To measure the spindle length in cells overexpressing Kip3 variants, cells were arrested in S phase by treating with 0.1 mM hydroxyurea for 3 h, followed by replacing 2% raffinose with 2% galactose in the media, and incubating for another 2.5 h in the presence of hydroxyurea before imaging. To determine the timing of bipolar spindle formation, cells were synchronized by treatment with 20 μM alpha factor for two hours. Cells were then released from the G1 block and collected at the indicated time points. Paraformaldehyde (3.7%) was then added. Samples were fixed for 8 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, and stored at 4 °C before imaging. To determine whether overexpressing Kip3-CC rescues the defects in forming bipolar spindles in cin8-3 kip1Δ cells, cells were grown to log phase in SC media supplemented with 2% raffinose at 24 °C and then arrested in S phase by 0.1 mM hydroxyurea for 3 h. The expression of Kip3 variants was induced by replacing 2% raffinose with 2% galactose for 3 h. Finally cells were shifted to 37 °C for 1 h to inactivate Cin8 before imaging. To perform time-lapse imaging to monitor astral microtubule dynamics and spindle elongation dynamics, a coverslip/double-sided tape/glass slide sandwich chamber of 50 μl was used and pre-coated with 0.5 mg ml−1 concanavalin A. Cells were then flowed into the chamber and the chamber was inverted to allow cells to bind to the coverslip. Unbound cells were then washed away by three chamber volumes of SC media before imaging.

Cellular images were acquired using a Zeiss AX10 microscope equipped with a CoolSnap HQ camera (Roper Scientific). A Z-focal plane series of images (7 planes with 0.75 μm between adjacent planes) was captured with a ×63 1.4 NA oil-immersion objective. The spindle lengths were determined by measuring the distance between thecentroid of Spc42-marked spindle pole bodies in three dimensions. The fluorescence intensity of individual proteins was measured from a maximal intensity projection from the Z-stack. Cellular background was subtracted for quantification. To monitor astral microtubule dynamics, images were acquired every 6 s for 10 min. Microtubule growth rates and shrinkage rates were obtained by fitting the time–length plot to a linear regression line. Microtubule catastrophe and rescue rates were calculated by dividing the number of events by the total microtubule lifetime. To monitor spindle elongation dynamics, images were acquired every 1 min for 90 min. Spindle elongation rates were obtained by fitting the time–length plot to a linear regression line.

Western blotting.

Standard procedures were used for western blotting. Mouse anti-GFP antibody (7.1 and 13.1, Roche, 11814460001) was used in a 1:1,000 dilution. Rat anti-α-tubulin antibody (YOL 1/34, Accurate Chemical & Scientific, YSRTMCA78G) was used at a 1:3,000 dilution. Representative immunofluorescence images and western blots were shown in Figs 1, 3, 5, S6 and S7. Each of these experiments was repeated at least three times.

Flow cytometry.

Cells were grown to log phase and fixed in 70% ethanol for two hours. Cellular RNA was digested by 0.25 mg ml−1 RNase in 50 mM sodium citrate, at pH 7 overnight at 37 °C. Then DNA was stained by 0.015 μg μl−1 propidium iodide for one hour at room temperature. FACS analysis was performed with a FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Statistical analysis.

Significance was calculated using a two-tailed Student t-test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Values are reported as mean±s.e.m.

References

Severin, F., Habermann, B., Huffaker, T. & Hyman, T. Stu2 promotes mitotic spindle elongation in anaphase. J. Cell Biol. 153, 435–442 (2001).

Goshima, G., Saitoh, S. & Yanagida, M. Proper metaphase spindle length is determined by centromere proteins Mis12 and Mis6 required for faithful chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 13, 1664–1677 (1999).

Goshima, G. & Scholey, J. M. Control of mitotic spindle length. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 26, 21–57 (2010).

Meunier, S. & Vernos, I. Microtubule assembly during mitosis—from distinct origins to distinct functions? J. Cell Sci. 125, 2805–2814 (2012).

Gatlin, J. C. & Bloom, K. Microtubule motors in eukaryotic spindle assembly and maintenance. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 248–254 (2010).

Winey, M. & Bloom, K. Mitotic spindle form and function. Genetics 190, 1197–1224 (2012).

Tanenbaum, M. E., Macurek, L., Galjart, N. & Medema, R. H. Dynein, Lis1 and CLIP-170 counteract Eg5-dependent centrosome separation during bipolar spindle assembly. EMBO J. 27, 3235–3245 (2008).

Saunders, W., Lengyel, V. & Hoyt, M. A. Mitotic spindle function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires a balance between different types of kinesin-related motors. Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 1025–1033 (1997).

Sharp, D. J., Yu, K. R., Sisson, J. C., Sullivan, W. & Scholey, J. M. Antagonistic microtubule-sliding motors position mitotic centrosomes in Drosophila early embryos. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 51–54 (1999).

Gupta, M. L. Jr, Carvalho, P., Roof, D. M. & Pellman, D. Plus end-specific depolymerase activity of Kip3, a kinesin-8 protein, explains its role in positioning the yeast mitotic spindle. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 913–923 (2006).

Varga, V. et al. Yeast kinesin-8 depolymerizes microtubules in a length-dependent manner. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 957–962 (2006).

Mayr, M. I. et al. The human kinesin Kif18A is a motile microtubule depolymerase essential for chromosome congression. Curr. Biol. 17, 488–498 (2007).

Du, Y., English, C. A. & Ohi, R. The kinesin-8 Kif18A dampens microtubule plus-end dynamics. Curr. Biol. 20, 374–380 (2010).

Gardner, M. K., Zanic, M., Gell, C., Bormuth, V. & Howard, J. Depolymerizing kinesins Kip3 and MCAK shape cellular microtubule architecture by differential control of catastrophe. Cell 147, 1092–1103 (2011).

Su, X., Ohi, R. & Pellman, D. Move in for the kill: motile microtubule regulators. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 567–575 (2012).

Goshima, G., Wollman, R., Stuurman, N., Scholey, J. M. & Vale, R. D. Length control of the metaphase spindle. Curr. Biol. 15, 1979–1988 (2005).

West, R. R., Malmstrom, T. & McIntosh, J. R. Kinesins klp5(+) and klp6(+) are required for normal chromosome movement in mitosis. J. Cell Sci. 115, 931–940 (2002).

Garcia, M. A., Koonrugsa, N. & Toda, T. Two kinesin-like Kin I family proteins in fission yeast regulate the establishment of metaphase and the onset of anaphase A. Curr. Biol. 12, 610–621 (2002).

Stumpff, J., von Dassow, G., Wagenbach, M., Asbury, C. & Wordeman, L. The kinesin-8 motor Kif18A suppresses kinetochore movements to control mitotic chromosome alignment. Dev. Cell 14, 252–262 (2008).

Wargacki, M. M., Tay, J. C., Muller, E. G., Asbury, C. L. & Davis, T. N. Kip3, the yeast kinesin-8, is required for clustering of kinetochores at metaphase. Cell Cycle 9, 2581–2588 (2010).

Su, X. et al. Mechanisms underlying the dual-mode regulation of microtubule dynamics by Kip3/kinesin-8. Mol. Cell 43, 751–763 (2011).

Woodruff, J. B., Drubin, D. G. & Barnes, G. Mitotic spindle disassembly occurs via distinct subprocesses driven by the anaphase-promoting complex, Aurora B kinase, and kinesin-8. J. Cell Biol. 191, 795–808 (2010).

Varga, V., Leduc, C., Bormuth, V., Diez, S. & Howard, J. Kinesin-8 motors act cooperatively to mediate length-dependent microtubule depolymerization. Cell 138, 1174–1183 (2009).

Fink, G. et al. The mitotic kinesin-14 Ncd drives directional microtubule–microtubule sliding. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 717–723 (2009).

Braun, M., Drummond, D. R., Cross, R. A. & McAinsh, A. D. The kinesin-14 Klp2 organizes microtubules into parallel bundles by an ATP-dependent sorting mechanism. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 724–730 (2009).

Kapitein, L. C. et al. The bipolar mitotic kinesin Eg5 moves on both microtubules that it crosslinks. Nature 435, 114–118 (2005).

Van den Wildenberg, S. M. et al. The homotetrameric kinesin-5 KLP61F preferentially crosslinks microtubules into antiparallel orientations. Curr. Biol. 18, 1860–1864 (2008).

Portran, D., Gaillard, J., Vantard, M. & Thery, M. Quantification of MAP and molecular motor activities on geometrically controlled microtubule networks. Cytoskeleton 70, 12–23 (2012).

Pellman, D., Bagget, M., Tu, Y. H., Fink, G. R. & Tu, H. Two microtubule-associated proteins required for anaphase spindle movement in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 130, 1373–1385 (1995).

Roostalu, J., Schiebel, E. & Khmelinskii, A. Cell cycle control of spindle elongation. Cell Cycle 9, 1084–1090 (2010).

Miki, H., Okada, Y. & Hirokawa, N. Analysis of the kinesin superfamily: insights into structure and function. Trends Cell Biol. 15, 467–476 (2005).

Klumpp, L. M., Mackey, A. T., Farrell, C. M., Rosenberg, J. M. & Gilbert, S. P. A kinesin switch I arginine to lysine mutation rescues microtubule function. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 39059–39067 (2003).

Gardner, M. K. et al. The microtubule-based motor Kar3 and plus end-binding protein Bim1 provide structural support for the anaphase spindle. J. Cell Biol. 180, 91–100 (2008).

Subramanian, R. et al. Insights into antiparallel microtubule crosslinking byPRC1, a conserved nonmotor microtubule binding protein. Cell 142, 433–443 (2010).

Gandhi, S. R. et al. Kinetochore-dependent microtubule rescue ensurestheir efficient and sustained interactions in early mitosis. Dev. Cell 21, 920–933 (2011).

Hoyt, M. A., He, L., Loo, K. K. & Saunders, W. S. Two Saccharomyces cerevisiae kinesin-related gene products required for mitotic spindle assembly. J. Cell Biol. 118, 109–120 (1992).

Cahu, J. & Surrey, T. Motile microtubule crosslinkers require distinct dynamic properties for correct functioning during spindle organization in Xenopus egg extract. J. Cell Sci. 122, 1295–1300 (2009).

Straight, A. F., Sedat, J. W. & Murray, A. W. Time-lapse microscopy reveals unique roles for kinesins during anaphase in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 143, 687–694 (1998).

Tanenbaum, M. E. et al. Kif15 cooperates with eg5 to promote bipolar spindle assembly. Curr. Biol. 19, 1703–1711 (2009).

Stumpff, J. et al. A tethering mechanism controls the processivity and kinetochore-microtubule plus-end enrichment of the kinesin-8 Kif18A. Mol. Cell 43, 764–775 (2011).

Weaver, L. N. et al. Kif18A uses a microtubule binding site in the tail for plus-end localization and spindle length regulation. Curr. Biol. 21, 1500–1506 (2011).

Mayr, M. I., Storch, M., Howard, J. & Mayer, T. U. A non-motor microtubule binding site is essential for the high processivity and mitotic function of kinesin-8 Kif18A. PLoS One 6, e27471 (2011).

Gatt, M. K. et al. Klp67A destabilises pre-anaphase microtubules butsubsequently is required to stabilise the central spindle. J. Cell Sci. 118, 2671–2682 (2005).

Savoian, M. S. & Glover, D. M. Drosophila Klp67A binds prophase kinetochores to subsequently regulate congression and spindle length. J. Cell Sci. 123, 767–776 (2010).

Hovland, P., Flick, J., Johnston, M. & Sclafani, R. A. Galactose as a gratuitous inducer of GAL gene expression in yeasts growing on glucose. Gene 83, 57–64 (1989).

Schuyler, S. C. & Pellman, D. Analysis of the size and shape of protein complexes from yeast. Methods Enzymol. 351, 150–168 (2002).

Hoskins, A. A. et al. Ordered and dynamic assembly of single spliceosomes. Science 331, 1289–1295 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Reck-Peterson Laboratory at Harvard Medical School for sharing the usage of their TIRF microscope. We appreciate H. Li’s help with FACS analysis. We thank M. Gupta and R. Ohi for suggestions and comments on the manuscript. D. Pellman is supported by Howard Hughes Medical Institute and a National Institute of Health grant (GM61345). M. Thery is supported by the Human Frontier Scientific Program (RGY0088/201). H. Arellano-Santoyo is an international fellow of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.S. and D. Pellman conceived the project and wrote the manuscript. H.A-S. performed the assay measuring microtubule dynamics and analysed the data. D. Portran, J.G., M.V. and M.T. performed the micropattering assay and analysed the data. X.S. performed the remainder of the experiments and analysed the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Integrated supplementary information

Supplementary Figure 1 Protein purification panel and demonstration of Kip3-CC dimer formation.

Coomassie staining after SDS-PAGE was used to visualize Kip3, Kip3ΔT-LZ (Kip3 without its tail domain), Kip3-CC (Kip3 with its neck replaced with leucine zipper), and Kip3-M (Kip3 motor domain) with or without EGS [ethylene glycol-bis (succinic acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester)] cross-linking. Note that after cross-linking Kip3-CC migrated at approximately the predicted size of a dimer, as Kip3 did. In contrast, Kip3-M remains at the similar position before and after cross-linking. Protein input: 1 μg.

Supplementary Figure 2 Comparable amounts of Kip3 and Kip3ΔT-LZ on track microtubules, related to the sliding assay in Fig. 1b.

(LEFT) TMR-labeled Kip3 or Kip3ΔT-LZ decorated track microtubules in the sliding assay. Scale bar: 5 μm. (RIGHT) Quantification of fluorescence intensity of Kip3 and Kip3ΔT-LZ along track microtubules at the beginning of sliding assays. Shown is mean±s.e.m. (N = 30 microtubules). Protein input: 150 nM.

Supplementary Figure 3 Categories of possible microtubule movements mediated by Kip3.

In each of the six situations, the bottom microtubule is immobilized to coverslip (blue bar). Kip3 motors, upright or inverted, slide the top cargo microtubules. The sliding direction was described as “ +”, “ −”, or “ +/−”, which indicates plus end-leading, minus end-leading, or tug-of-war, respectively. The microtubule orientation is indicated as being ‘p’ (parallel) or ‘a’ (anti-parallel). The observed frequencies for each type of movements was listed (N = 110 microtubule pairs).

Supplementary Figure 4 Kip3 slides anti-parallel microtubules and occasionally parallel microtubules.

Polarity-labeled microtubules (bright red for the plus end of cargo microtubules and bright green for the plus end of track microtubules) show an anti-parallel orientation (#1–#3) and a parallel orientation (#4). “ +” and “ −” indicate the microtubule plus end and minus end, respectively. Scale bar: 5 μm. Kymographs at the bottom show sliding movement of the numbered cargo microtubules. Scale bar: 2 μm (horizontal) and 2 min (vertical). Kip3 input: 150 nM.

Supplementary Figure 5 Kip3 induces the formation of curvy microtubule bundles.

Image panels show examples of curvy microtubule bundles in the presence of 10 μM tubulin together with indicated proteins (50 nM of Kip3 or/and 33 nM of Ase1). The images were taken 30 min after the reaction was started. Note that this panel does not include the substantial amount of asters pairs that were either non-connected or connected by straight bundles. The quantification of overall bundle curvature (including straight bundles) is shown in Fig. 2c. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Supplementary Figure 6 Comparable fluorescence intensities of motors along microtubules in the dynamic microtubule assay in Fig. 3.

(a) Kymographs show microtubule dynamics in the presence of Kip3 or Kip3-CC. (TOP) HiLyte 647-labeled tubulin. (BOTTOM) TMR-labeled motor. Input: 150 nM Kip3, 6 nM Kip3-CC. Scale bar: 5 μm (horizontal) and 1 min (vertical). b) Quantification of fluorescence intensity of Kip3 and Kip3-CC along microtubules. Shown is mean±s.e.m. (N = 47 and 50 microtubules for Kip3 and Kip3-CC, respectively). c) Quantification of the growth and shrinkage rates, related to Fig. 3e. Shown is mean±s.e.m. (N = 71, 46, and 63 growth events for Kip3, Kip3-CC, and control, respectively; N = 164, 25, and 23 shrinkage events for Kip3, Kip3-CC, and control, respectively). P value was obtained from a two-tailed Student’s T test.

Supplementary Figure 7 The spindle localization of Ase1 and Stu2 in cells overexpressing Kip3-CC.

(a) Representative images of a control cell and a cell overexpressing Kip3-CC. These cells were synchronized in S phase by hydroxyurea. Microtubules were labeled with CFP-Tub1. Ase1 was visualized with a 3xYFP tag. Scale bar: 2 μm. b) Comparison of spindle-associated Ase1 and spindle length between control cells and cells overexpressing Kip3-CC. Shown is mean+s.e.m. (N = 50 cells). c) Representative images of a control cell and a cell overexpressing Kip3-CC. Microtubules were labeled with CFP-Tub1. Stu2 was tagged with EYFP. Scale bar: 2 μm. d) Comparisons of the fluorescence intensity of Stu2 at mid region of pre-anaphase spindles (arrows in Supplementary Fig. S7c) between control cells and cells overexpressing Kip3-CC. Shown is mean+s.e.m. (N = 64 cells).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information (PDF 664 kb)

Kip3-driven sliding and ‘tug-of-war’ movements of stabilized microtubules.

Cargo microtubules (red) move along track microtubules (green) in the presence of 150 nM Kip3. Videos play at 300× speed. Field view: 27×60 μm. (MOV 3247 kb)

Rare flipping of cargo microtubules in the sliding assay.

Cargo microtubules (red) move along track microtubules (green) in the presence of 150 nM Kip3. Videos play at 300× speed. Shown is sliding followed by flipping over and sliding in the opposite direction. This is a rare event, which was found in 4 out of 300 microtubule pairs. Scale bar: 1 μm. (MOV 77 kb)

A control for micropatterned sliding assay.

Dynamic microtubules (green) were growing from seeds (red) adsorbed on micropatterned sites. Scale bar: 10 μm. (MOV 130 kb)

Kip3-mediated buckling of dynamic microtubules.

Dynamic microtubules (green) were growing from seeds (red) adsorbed on micropatterned sites in the presence of 50 nM Kip3. One microtubule bundle started to buckle around 13:00. Scale bar: 10 μm. (MOV 127 kb)

Ase1-induced microtubule bundles.

Dynamic microtubules (green) were growing from seeds (red) adsorbed on micropatterned sites in the presence of 33 nM Ase1. Straight and stable bundles were formed. Scale bar: 10 μm. (MOV 124 kb)

Kip3-mediated buckling of Ase1 bundled microtubules.

Dynamic microtubules (green) were growing from seeds (red) adsorbed on micropatterned sites in the presence of 50 nM Kip3 and 33 nM Ase1. A stable microtubule bundle steadily buckled and elongated. Scale bar: 10 μm. (MOV 103 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Su, X., Arellano-Santoyo, H., Portran, D. et al. Microtubule-sliding activity of a kinesin-8 promotes spindle assembly and spindle-length control. Nat Cell Biol 15, 948–957 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb2801

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb2801

This article is cited by

-

Kinesin-8 motors: regulation of microtubule dynamics and chromosome movements

Chromosoma (2020)

-

Kif18a regulates Sirt2-mediated tubulin acetylation for spindle organization during mouse oocyte meiosis

Cell Division (2018)

-

Organization of microtubule assemblies in Dictyostelium syncytia depends on the microtubule crosslinker, Ase1

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2016)

-

Mad1 promotes chromosome congression by anchoring a kinesin motor to the kinetochore

Nature Cell Biology (2015)

-

Prime movers: the mechanochemistry of mitotic kinesins

Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology (2014)