Abstract

Foldamers are sequence-specific oligomers akin to peptides, proteins and oligonucleotides that fold into well-defined three-dimensional structures. They offer the chemical biologist a broad pallet of building blocks for the construction of molecules that test and extend our understanding of protein folding and function. Foldamers also provide templates for presenting complex arrays of functional groups in virtually unlimited geometrical patterns, thereby presenting attractive opportunities for the design of molecules that bind in a sequence- and structure-specific manner to oligosaccharides, nucleic acids, membranes and proteins. We summarize recent advances and highlight the future applications and challenges of this rapidly expanding field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

As the database of protein structures grows, so too does our interest in testing the molecular basis for folding and function. We have developed an understanding of the importance of noncovalent interactions in regulating protein folding, assembly and catalysis; this understanding has now been put to the test through the successful computational design of proteins from scratch1,2,3. However, the rules used in these studies have been largely developed with peptides and proteins composed of α-amino acids, which leads to the question of whether our understanding is overly parameterized and specific to conventional peptides, or whether it is truly molecular in nature. To address this question, it is important to extend the systems to new nonbiological structures, thereby critically testing our understanding of biological structure while simultaneously developing new building blocks and molecular frameworks for the design of pharmaceuticals, diagnostic agents, nanostructures and catalysts. By changing the identity of the backbone, we enter into fundamental questions regarding rules of folding; hence the recent interest in “foldamers”4.

Because of the diversity of sizes, shapes and arrangements available with non-natural monomers, this field offers a myriad of opportunities for designs of molecular interaction modules supported by foldamer frameworks. The creation of these frameworks has already resulted in many intellectually useful and functionally interesting molecules. Already, there are multiple examples of functional foldamers capable of mediating cell penetration5,6, as well as designed foldamers that specifically bind to various targets including RNA7, proteins8,9,10,11,12,13,15, membranes16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,25, and carbohydrates26, often with affinities approaching or equaling those of natural α-peptides. And as more versatile frameworks are created it will be increasingly possible to design foldamers that bind most any surface. Indeed, we are only beginning to scratch the surface of this field. This review briefly discusses some of the diverse foldamers structures available for design, their conformations, and their applications in chemical biology, with a particular focus on the significant progress made in the last few years. Given the breadth of the field, we will focus primarily on foldamers whose conformations are stabilized by hydrogen bonds.

Framework selection

There are two general molecular classes of foldamers, determined by the presence or absence of aromatic units within the monomer unit (Fig. 1). “Aliphatic” foldamers have saturated carbon chains separating amide or urea groups. Example of this group include the β-27,28, γ-29 and δ-30,31, oligoureas32, azapeptides33,34, pyrrolinones35, α-aminoxy-peptides36 and sugar-based peptides37,38. The second class makes use of aromatic spacers within the backbone. The poly-pyrrole/imidazole DNA-binding oligomers39 provided early examples of heteroaryl oligomers that bind biologically relevant targets. In either case, the initial monomer selection is typically affected by a variety of factors, including the ease of their synthesis and structural characterization (Box 1).

Dehydropeptides40, peptoids41,42,43, and foldamers prepared by mixing aliphatic and aromatic units44,45,46 are related classes of foldamers which, although interesting, will not be considered in this review.

Secondary structures formed by aliphatic foldamers

The secondary structure formed by a given type of amide foldamer depends on the planar amide bonds, the number and substitution patterns of the methylene units within the backbone, and conformational restraints such as the incorporation of cyclic structures within the amino acid. The helices formed by foldamers are characterized by their handedness and the number of atoms within repeating hydrogen bonding rings of their structures. A second feature of the helix is the orientation of the amide groups; hydrogen bonding generally causes the carbonyl of successive amides to either point toward the N terminus or the C terminus, thereby giving rise to exposed amides at the ends of the helices. In conventional peptides, the main conformations are 310- and α-helices, with 10 atoms and 13 atoms in the hydrogen bonded rings. What happens when additional methylene groups are inserted between the amides of the monomers depends on the placement and stereochemistry of side chains along the backbone27,28,41,47 (Table 1). β-peptides in which the monomer is a trans-2-amino-cyclopentane-carboxylic acid (or cyclized residues in which the β2 and β3 positions are part of a five-membered ring) adopt a “12-helix” conformation, with the same hydrogen bonding pattern as the 310-helix of α-peptides, but with two additional carbon atoms inserted into the backbone. Park et al. examined the impact of incorporating acyclic residues into this structure using a series of peptides, with one to four β2-substituted residues present in a background of cyclized amino acids48. Although the helical propensity was lower because of the incorporation of the β2 residues, the 12-helix previously observed to be the predominant form for cyclic residues remained the favored structure.

Other substitution patterns of β-peptides (including residues constructed from cyclohexane rings or β3-substituted residues) favor the 14-helix, which bears both similarities and differences to the α-helix. The 14-helix has two intervening amide units within each hydrogen bonded ring (as in the α-helix), but the amide carbonyl groups are directed toward the N terminus rather than the C terminus as in the α-helix. Other helical conformations (Table 1), as well as turn and sheet-like conformations, are also possible27,49,50, and new conformations continue to surface. For example, the effect of varying substitution patterns can be seen in the recently discovered 8-helix, observed when both β2 and β3 positions are substituted in each monomer51,52, or in the 10/12-helix, seen for sequences displaying an alternating β2- and β3-substitution pattern28.

The β3-substituted residues are under particularly intense investigation at the moment because of the ready availability of monomers through homologation of α-amino acids, which also results in their nomenclature; for example, arginine becomes homoarginine, abbreviated hArg (note that 3-amino-propionic acid has traditionally been called β-alanine, but in this nomenclature it can also be designated as hGly). Peptides composed of β3-substituted amino acids have a high propensity to form 14-helices (Fig. 2a,b). The features that stabilize this conformation in β-peptides have, in general, been well anticipated by studies with α-peptides. Salt bridges between oppositely charged residues spaced one turn apart (i, i + 3 in 14-helices and i, i + 4 in an α-helix) stabilize both types of helices28,53,54. These salt bridges are extremely sensitive to their specific structural context; the mismatch of alkyl chain length between two neighboring point charges can greatly change the stability afforded to the 14-helix55. Also, as in the α-helix, appropriately charged side chains near the ends of the helices can interact with the exposed backbone amides near the ends of 14-helices56. However, because the carbonyl groups in the 14-helix point in a direction opposite to that of the α-helix, the requirements for charged groups are reversed. Indeed, charged terminal backbone amino and carboxyl groups stabilize the 14-helix (Fig. 2c), but are destabilizing to the α-helix. Other design principles that can be translated directly from our understanding of α-amino acids include helix stabilization by introduction of disulfides57 or covalent bridges58, or by binding of metal ions between ligating residues spaced one helical turn apart49. The helical propensities of individual residues can also be qualitatively rationalized on the basis of the 14-helical structure: the geometry dictating the interactions between side chains separated by one turn of a 14-helix is more similar to that observed in β-sheets than α-helices (Fig. 3). Thus, one would expect that amino acid propensities for 14-helices would be distinct from those for the α-helices, and more dependent on interactions with neighboring side chains, as has been shown to be the case for β-sheets59. Indeed, β-branched residues such as valine, which are 'α-helix breakers' but β-sheet formers in proteins, actually stabilize the 14-helix in water60.

(a) The most studied β-peptide helix, the 14-helix, is named as such because of the 14-membered ring formed when the i and i + 3 amides form a hydrogen bond. (b) Crystal structure of a 14-helix highlighting backbone hydrogen bonds. (c) 14-helix conformation depicting N-terminal and C-terminal capping motifs. Also shown, electrostatic pairing between oppositely charged side chains at i and i + 3 residues, as well as hydrophobic side chains at i, i + 3 that are clustered in the crystal structure. Crystal structures are from ref. 61.

Interactions between substituents at C3 of residues i, i + 3 in the 14-helix; distances range from 4.7 Å to 5.2 Å in the crystal structure of Zwit-1F (ref. 61). The corresponding cross-strand distance ranges from 4.5 Å to 5.5 Å in a β-sheet (Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 1TTA), and the i, i + 4 distances range from 5.9 Å to 6.5 Å in an α-helix (PDB code 2ZTA). Mixed α/β-peptide (side and top views shown): overlay of the α-helix and a helix formed in a mixed α/β-peptide (the additional backbone C2 methylene groups are shown as spheres in the β-amino acid) (PDB codes 2ZTA and 2OXJ)70.

A recent crystal structure of a designed β-peptide has confirmed many of these principles, such as the salt bridges previously discussed61. In addition, not only does one observe the expected i, i + 3 hydrogen bonds between backbone amides, but also possible CH···O=C hydrogen bonds (Fig. 2b). Hydrogen atoms on the acidic, unsubstituted backbone C2 methylene groups (α to the carbonyl groups) closely approach the main chain carbonyls in what is often classified as a CH hydrogen bond62. Indeed, Mathad et al. showed that substitution of this prochiral hydrogen for a fluorine atom disrupts the formation of the 14-helix63. Although these hydrogen bonds are weaker than those involving amide protons, they might contribute to stability. This interaction could in fact begin to explain the greater conformational stability observed for short β-peptides versus α-peptides.

Heterogeneous backbones

What happens when two classes of amino acid building blocks (for example, α- and β-amino acids) are present in a single peptide? Early work along these lines64,65 showed that β-amino acids can encourage turn formation in peptides. Additional exploration of sequence space has identified several non-natural residue combinations that are particularly well suited to serve as turns or β-hairpin initiators (for reviews, see refs. 28,41,66). A single β-amino acid is also well tolerated within the α-helix (Fig. 3), with local distortions to allow insertion of a single methylene unit67. Only recently have the effects of the systematic alternation of α- and β-amino acids in repeating sequences been examined68,69. Many of the resulting structures may be anticipated as simple modifications of the common 310- or α-helical conformations of conventional peptides; the 310-helix (with hydrogen bonding between the amide proton of residue i and the carbonyl of i + 3) expands from repeating 10-atom hydrogen rings to 11-atom rings in (α-β)n peptides (α and β refer to α- and β-substituted amino acids, respectively), whereas the α-helix expands from 13 to 14 atoms in peptides with (α-α-β)n patterns (Table 1)67. The 11-helix has been crystallographically characterized66, and solution studies show that previously established rules hold in this new context: α,α-disubstituted α-amino acids and cyclic β-amino acids, which are known to stabilize helices in other circumstances, were again stabilizing for the hybrid sequence. Similarly, crystallographic studies with another α-α-β peptide led to a local 14-helix structure related to the α-helix by insertion of a single atom67, and a peptide with a repeating β-α2-β-α3 backbone70 forms a modification on the α-helix as shown in Figure 3.

In α-peptides there is a facile interconversion between 310- and α-helical conformations on a relatively flat energy landscape, particularly for short peptides71,72. Peptides composed of 1:1, 1:2 or 2:1 sequences of α-amino acids mixed with cyclic β-residues73,74 similarly interconvert between hydrogen bonding patterns involving residues i and either i + 3 or i + 4. Exploring heterogeneous backbone space further, recent studies have demonstrated that different combinations of natural and non-natural monomers similarly result in new structures, many of which are summarized in Table 1: α-amino acids with noncyclic β-amino acids make 9/11-helices75; α-amino acids with γ-amino acids make 12/10-helices76 and 12-helices67; β-amino acids with γ-amino acids make 11/13-helices76; and α-amino acids with aromatic monomers make structures that defy conventional naming schemes77. Vasudev et al. recently reviewed the growing literature concerning structures that can be formed between various amino acids, and the principles that can be gleaned from these studies78. Taken together, the structures observed with peptides with heterogeneous backbones offer unprecedented fine control over the display of individual substituents for functional studies.

Design: aromatic oligomers

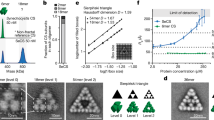

Among the most well-studied aryl-based foldamers are the aromatic oligomers based on oligoamides and oligoureas. Like the development of well-defined secondary structures of peptides, the construction of new structural features of the aromatic foldamers requires consideration of localized noncovalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions, but here π-π stacking and specific geometric constrains also have significant roles in secondary and tertiary structure organization. Additionally, the interactions in this case are often more local; usually hydrogen bonding occurs from one monomer to the next, thereby limiting the need to consider as many alternative folded states. As this is a particularly large field, and design principles have recently been reviewed79,80, we will provide the reader with only the briefest summary of these properties. To generate backbone-rigidified aromatic foldamers that form extended, bent, and helical conformations, selection of the monomer unit is key. The main considerations for structural design are the size of the monomer and the substitution pattern of the aromatic ring; indeed, knowing the size of the repeat unit and substitution pattern provides a reliable predictive method for determination of helical radius79,80,81,82 (Fig. 4). Even the stability or handedness of the helix can be controlled by the monomer choice83. For compounds that form a helical structure, hydrogen bonds that stabilize the structure or discriminate between two or more potential folded states are typically located either in the helix interior (Fig. 4a,b)84, exterior (Fig. 4c)45, or even both locations85. In addition to the normal palette of N- and O-centered hydrogen bonds, F...HN bonds provide an efficient tool in the development of foldamers86. Helical conformations can additionally be regulated by a variety of factors, including the use of chiral auxiliaries, uneven spacing between aromatic rings, and environmental controls such as protonation state or choice of solvent, or often a mixture of these87,88,89,90,91. Furthermore, as in aliphatic foldamers, interactions between pendant 'side chains' extending from a helix can further stabilize the overall structure92.

(a–c) Examples of hydrogen bonding patterns used in foldamer scaffolds that have been shown to form helix-like structures with indicated repeating subunits88. (d) Linear foldamer stabilized by hydrogen bonding network26. (e) The precise spacing of carboxylates on an arylamide framework promotes the formation of calcite (CaCO3) crystals in a specific morphology96.

In contrast to helical structures, several hydrogen bonding patterns have been designed to promote linear foldamer conformations. The linear forms can be stabilized in 3-substituted arylamides by inclusion of hydrogen bonding groups that stabilize adjacent amides in the appropriate orientation, and/or judiciously positioned heteroatoms in the neighboring aryl rings (Fig. 4d,e) (for reviews, see refs. 79,93,94). The stability of the linear molecule, in combination with the known spacing of substituents along the oligomer backbone, has made this general structure a preferred framework for the display of functional groups approximating the side chains of an α-helix95. Alternately these arylamides have been used as frameworks for other applications, such as the display of linear arrays of carboxylates that modify the growth of calcite crystals (Fig. 4e)96.

Finally, oligomers have been designed that associate to form dimeric complexes. Specifically, oligomers constructed from 2,6-pyridinedicarboxylic acid and 2,6-diaminopyridine can combine to form a homodimeric double helix (Fig. 5)79,87. Because the spacing between strands is based on π- π stacking, the overall conformation has much in common with the DNA double helix. In contrast to DNA strands, however, there is a marked length dependence in the percentage of double versus single helices observed97, with intermediate lengths favoring the double helix and shorter or longer lengths more likely to adopt the single helix. Because the behavior of this particular oligomer can be tuned by many environmental factors as discussed above, it is likely to serve as an interesting case in developing our understanding of the thermodynamics controlling foldamers in general.

Structure and association of monomeric and dimeric foldamers87.

Engineering function: β-peptides

In addition to the design of conformationally constrained frameworks to address fundamental questions of folding, aliphatic oligomers have been used to address problems in molecular recognition with metal ions, proteins, oligonucleotides, membranes and carbohydrates (Supplementary Table 1 online). Much work has focused on design of cationic foldamers that use electrostatic interactions to bind to membrane or oligonucleotide surfaces. For example, many studies (using both aliphatic and aromatic frameworks) have developed polycationic foldamers that interrupt Tat/TAR binding (see, for example, ref. 7). Additionally, homolysine-rich β-peptides have been developed as delivery vectors for gene therapy, simultaneously demonstrating productive interactions with both membranes and DNA98. Homoarginine oligomers5 and more diverse homoarginine-containing peptides6 are also able to mediate transport into mammalian cells, and do so in a chain-length-dependent manner. In some cases these peptides enter cells by endocytosis and then escape the endosomal compartment in a mechanism requiring endosome acidification, whereas in other cases the peptides are able to enter cells in what seems to be an endocytosis-independent process based on the fact that the cells gain entry into the cell even at 4 °C and in the presence of NaN3 (ref. 99). Interestingly, β3-oligohomoarginines are able to penetrate bacterial cells in what seems to be a passive process100, which suggests the same is true for the natural counterpart.

In some biological applications, the presentation of polar and apolar groups along distinct faces of a secondary structure is important, although the precise nature of these side chains may not be critical. This amphiphilic display is characteristic of amphiphilic helices such as apolipoproteins, which are known to impede cholesterol uptake in the small intestine. Amphiphilic 14-helical β-peptides also inhibit this process, most probably through interactions with the transport protein SR-BI (ref. 99). Amphiphilic helices are also observed in antimicrobial peptides, products of innate immunity that kill bacterial cells by disrupting their membranes. This feature can be captured within foldamers formed by β-peptides and peptides that contain α and β backbone units (α/β-peptides17,20,22,25,101,102, which has provided insight into the features required to selectively kill bacteria versus mammalian cells. Oligomers that were too long or too hydrophobic showed unacceptably high toxicities toward human erythrocytes, whereas oligomers with the appropriate length, amphiphilicity and hydrophilic/lipophilic balance were selective antimicrobial agents. Furthermore, there seemed to be no need to design a rigid, preorganized helix, so long as the helical conformation could be induced upon binding to the phospholipid surface. Even the ability to form an extended amphiphilic secondary structure—so often observed in natural antimicrobial peptides103—does not seem to be an absolute requirement104. Indeed, knowing that regular amphiphilicity is not required in antimicrobial agents inspired the construction of random polymethacrylate copolymers with significant and partially selective antimicrobial activity105 that were designed simply by varying the chain length and mole fraction of positively charged versus methacrylate monomers. Molecular dynamics calculations of the interaction of individual components of the polymeric mixture with phospholipid bilayers have shown that distinct regions of the polymers can insert into the apolar region of the bilayer, often in dynamically averaging conformations106.

Studies with antimicrobial β- and mixed α/β-peptides have been informative with respect to the mechanism of action of this class of compounds. Analysis of a large library of β-peptides forming a 12-helix was used to demonstrate that the β-peptides likely use the same mechanism for bactericidal action as their α-twins; the lower limit of efficacy of ∼1 μM suggests a mode of action at the membrane, rather than for a specific intracellular target101. Recent investigations of the mechanism of two antibacterial α/β hybrid peptides demonstrated a role for bacterial lipids in the antibacterial activity of the compounds22. In particular, one of the peptides was able to induce phase segregation of anionic and zwitterionic lipids (and thus toxicity), whereas the other was not.

The design of foldamers that inhibit protein-protein interactions provides a greater challenge that requires consideration of not only physicochemical properties such as charge and amphiphilicity, but also the precise placement of functional groups in three dimensions. Early work focused on short cyclic and linear β-peptides as mimics of somatostatin99. More recent work has focused on capturing the features of α-helices, as numerous protein-protein and protein-peptide interactions involve a single helix in one of the two partners. The topological similarities of the α- and β-helices allow 'mapping' of the α-helical residues onto a β-peptide structure (Fig. 3). Using this mapping approach, β-mimics of the p53 helix were designed that interrupted the hDM2-p53 interaction11,13,107,108; optimization of the initial sequence by creating a library to introduce substitutions along the noninteracting face of the helix resulted in a ∼10-fold improvement in the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50)109. β-peptides have also been used as mimics of enfuvirtide (Fuzeon), a peptide that inhibits human immunodeficiency virus fusion peptide14. Although the effector concentration for half-maximum response (EC50) of the most effective peptide is four orders of magnitude weaker than that of the α-peptide, enfuvirtide, the β-peptides are much smaller and have not yet been extensively optimized.

A similar strategy has resulted in highly selective inhibitors of human cytomegalovirus, which target the viral fusion protein glycoprotein gB (ref. 10). Extending this method to new frameworks has demonstrated the utility of mixed α/β sequences for disrupting the Bak–Bcl-xL interaction. By combining a mixed α/β sequence with an all-α sequence at the C terminus, the authors identified a sequence with a ten-fold higher affinity for Bcl-xL than the native peptide ligand110. This report highlights the importance of being able to continuously vary specific helical parameters by varying the backbone structure, as previous efforts to map the BH3 helix of Bak with purely 12- or 14-helix designs proved ineffective.

In contrast to the investigation of direct interactions with biological targets in solution, foldamers can also be used in biomaterial-inspired applications. Nanostructured materials are prominent in the natural world and are also often the targets of various attempts to engineer both hard and soft materials. Nanostructures from foldamers can be prepared by simply propagating the noncovalent forces mentioned above for the design of secondary structures over a longer scale to create ordered materials. This approach is nicely demonstrated by the use of cyclic β-amino acids that display trans or cis geometries between the amide and carbonyl substituents projecting from the ring111. For the trans system, vesicles are assembled from helices displaying 'vertical amphiphilicity', or the presence of the hydrocarbon rings on the helix exterior, whereas in the cis geometry, amyloid-type fibrils result from the extended conformation of the backbone. In another recent example, β-peptides were designed that form birefingent liquid crystals112, thereby providing a new approach to this class of materials.

Engineering function: aryl foldamers

Aryl foldamers have also proven to be versatile platforms for the design of bioactive mimics of natural proteins. As a starting point, studies of systems driven by electrostatic pairing have confirmed the ability of arylamides to take part in biological processes. For example, cationic arylamides were designed to bind heparin and interrupt the heparin-antithrombin interaction26 using a framework capable of displaying up to six substituents. As could perhaps be anticipated in binding such a highly charged target, the binding affinity increased with increasing charge and numbers of hydrogen bonding groups. A related framework has been used to create amphiphilic mimics (Fig. 6) of antimicrobial peptides113,114. As observed for antimicrobial β-peptides, optimization of the antimicrobial activity and minimization of toxicity required finding the proper balance of chain length, charge, amphiphilicity and hydrophobicity114,115. Compounds with decreased conformational freedom and increased efficacy were prepared by replacing a central phenyl with a pyrimidyl group in the backbone to form hydrogen bonds with neighboring amides (Fig. 6)94. Furthermore, based on these principles, the widely used phenylalkynyl foldamer framework116 was also used to produce polymers, and ultimately small molecules (MW < 600, Fig. 6) that are highly potent and selective antimicrobial agents that seem to work by the same mechanism as the host defense peptides that served as inspiration for their design117,118.

The structural simplicity of aryl-based antimicrobial compounds makes them excellent systems for computational and experimental studies concerning the mechanism of antimicrobial activity. For example, sum frequency generation vibrational spectroscopy has revealed that the antimicrobial arylamides119 insert into the bilayers with their long axes parallel to the membrane surface120. At concentrations below the IC50, the leaflet in contact with the oligomers was disturbed, whereas the other leaflet of the lipid bilayer was not disturbed. These studies are consistent with course-grained molecular dynamics simulations, which showed dose-dependent penetration into the outer leaflet of the bilayer at low arylamide/phospholipid ratios, and deeper penetration and overall perturbation of the bilayer packing at lytic arylamide/phospholipid ratios121.

As with β-peptides, the controlled display of functional groups on aromatic foldamer frameworks can be used to approximate the projections of side chains at positions i, i + 4, and i + 7 on one face of an α-helix. The terphenyl backbone is a successfully used framework that is devoid of hydrogen bonds (for a recent example, see ref. 122); other backbones use internal hydrogen bonds to 'lock in' the desired conformation while increasing the solubility of the structures. Recent efforts highlight the utility of these frameworks in interrupting protein-protein interactions: in particular, mimics of the BH3 helix from Bak have been used to disrupt the Bak–Bcl-xL interaction123. Optimization of the mimic generated additional binding energy by filling an apolar pocket on Bcl-xL, ultimately yielding a molecule with a Ki of 0.8 μM and an IC50 of 35 μM in a cellular assay124. A different arylamide scaffold has also been used to design mimics of the α-helical calmodulin-binding domain of smooth muscle light-chain kinase (smMLCK), resulting in a compound that binds to this protein with a Ki of 7.1 nM (Supplementary Fig. 1 online)125. NMR analysis of the smMLCK peptide and the arylamide mimic confirmed that the arylamide binds to calmodulin in a manner similar to that of the natural helix. In these and other examples, the aromatic frameworks have been particularly successful when there are additional interactions possible between the fairly nonpolar frameworks, which dock against hydrophobic spots on the protein of interest.

Toward predictable tertiary and quaternary structures

The above examples demonstrate the design of functional molecules based on aromatic and aliphatic foldamers that adopt well-defined secondary structures. Ultimately, however, many functions will require the greater functional complexity available from tertiary structures. Indeed, the design of oligomers that fold into unique tertiary structures is a grand challenge in foldamer research116 that probes our understanding of the mechanisms by which natural protein sequences fold into their native three-dimensional structures while also laying the groundwork for the design of complex protein-like functions. A significant step toward this goal through the design of a β-peptide intended to adopt a zinc finger–like motif was recently realized49. The 16-residue peptide consists of a β-hairpin and a 14-helix, both of which can individually bind Zn(II) as a bivalent ligand. The two Zn(II)-binding units have been individually characterized as isolated short peptides; together they are intended to bind Zn(II) in a tetrahedral hCys2-hHis2 geometry analogous to the geometry of Zn(II) fingers in transcription factors. As observed in the native counterpart, the peptide folds in the presence of Zn(II), and hence this represents an exciting step toward the design of entirely novel and uniquely structured foldamers. The ability to bind metal ions also provides an entrée into the vast array of metalloproteins that function as sensors and catalysts.

Other efforts have focused on the assembly of amphiphilic β-peptides into helical bundles and coiled coils similar to those seen in α-helical proteins. One early study reported a disulfide-linked pair of 14-helical peptides that had an unfolding curve appropriate for a tertiary structure of this size126; interfacial interactions between the two chains stabilized the desired secondary structure. More recent studies have focused on noncovalent self-assembly, including assemblies driven either by hydrogen bonding between nucleobase-functionalized helices (see for example ref. 127) or by hydrophobic packing of amphiphilic 14-helix peptides that reversibly associate to form discrete, water-soluble helical oligomers128,129. Recently these efforts have been expanded with the report of the crystal structure of a 12-residue β3-peptide, Zwit-1F (Fig. 7), which has provided new insight in the design of protein-like architecture61.

Crystal structure of designed β-peptide61 is shown; parallel dimer pairs are in blue and green. (a) β-peptide sequence mapped onto helical wheel. (b) Full octomeric structure, highlighting the parallel monomer chains within each subunit (hydrophobic packing of leucine and phenylalanine shown in pink). (c) Parallel helical interface with leucine packing highlighted. Also shown: top view, helical wheel. (d) Antiparallel helical interface with leucine packing highlighted. Also shown: top view, helical wheel.

The crystal structure of the octamer is composed of four copies of parallel helical dimers; two parallel dimers associate in an antiparallel manner to create tetramers, which further associate into an octamer with a well-packed hydrophobic core (Fig. 7b). The parallel helix dimer bears some similarities to a conventional parallel two-stranded coiled coil, which provided the inspiration for the original design: the positions within the 7-residue geometric repeat unit of α-helical coiled coils are represented using the letters “a” through “g,” with the “a” residue projecting toward the neighboring helix. In a similar manner we can assign the “a” residue of the three-residue structural repeat of Zwit-1F as the position pointed toward the neighboring helix (Fig. 7c). The amino acid sequence is threaded differently onto the two helices of the motif, which creates an offset between the two helices and allows interdigitation of the leucine side chains along one face of the structure. On the other hand, in the antiparallel dimer a pseudo-two-fold axis lies between the two helices (Fig. 7d), such that equivalent “a” positions line up on the same face of the helical pair, resulting again in a zipper-like arrangement of leucine side chains along the face of the dimer that is buried in the octameric structure. Because of the inclusion of an additional methylene in the backbone structure of β-amino acids, the surface of the 14-helix backbone is larger and more apolar than the α-helix. It therefore has a more direct role in direct helix-helix packing interactions. This feature, together with the geometry of packing of side chains, should help provide the essential details required to help calibrate and extend computational methods for the design of larger bundles with precisely predefined structures and functions.

Another very recent report describes the effects of systematic substitutions of β-amino acids into the two-stranded coiled coil from the transcription factor GCN4 (ref. 70). The substitutions were made along the polar side of the helix, to minimize disruption of the packing within the core of the coiled coil. The resulting peptide has a repeating sequence of (αa-βb-αc-αd-αe-βf-αg)n, in which the subscripts refer to the positions of the amino acids in the coiled coil repeat unit. Although the substitutions substantially destabilized the overall folding of the peptide in solution, it retained sufficient stability to crystallize as a trimeric coiled coil. The same α-to-β substitutions were examined in a variant of GCN4 that forms a tetramer in the conventional all-α peptide. The corresponding α/β-peptide formed a very stable trimer in solution but crystallized as a tetramer. The β-amino acid residues in both α/β structures are well accommodated, maintaining the overall helical geometry and hydrogen bonding pattern of the α-helix (Fig. 7). They also show classical knobs-into-holes packing of the side chains between the helices. However, in each context, the substitutions subtly alter the angle of projection of the β-amino acid side chains and the helical packing geometries, thereby altering the specificity and stability of the peptides for a given association state in solution. It will now be most interesting to determine how similar substitutions affect the structures and activities of a variety of globular proteins.

Foldamer research—coming of age?

It has now been over three decades since Karle's first examinations of the structures of cyclic peptides containing β-amino acids65, fifteen years since Zuckerman's ground-breaking work on N-alkyl glycine oligomers (peptoids)43, and a decade since Seebach's130 and Gellman's131,132 first studies of the secondary structure of β-peptides. However, chemical biologists have only recently begun to use foldamers to study protein-protein, protein-oligosaccharide, and peptide-membrane interactions. Also, the first protein-like structures of β-peptide and α/β assemblies were reported only this year. These areas of foldamer research are most likely to continue to expand in the coming years, and to play an increasingly large role in chemical biology.

The continued pursuit of new folded backbones, including hybrids of aromatic and aliphatic backbones, will lead to increasingly diverse platforms for recognition of a variety of biomolecules and surfaces. For example, foldamers are already beginning to show promise in pharmaceutical research. They are generally more stable to enzymatic attack than peptides99 and require fewer monomeric units to adopt well-defined secondary structures, thereby extending the promise of designing smaller and more stable versions of peptides (Fig. 4). Furthermore, they can be used as stepping stones in the downsizing of peptides to small molecules, as illustrated by work discussed above on antimicrobial peptides: the starting peptides had molecular weights in the range of 2,000 to 3,000 Da, those of the β-peptides were 1,000 to 2,000 Da, and the arylamides and phenylalkynyl compounds range from 500 to 1,000 Da (Fig. 6).

One might also expect to see increasing spillover of foldamer frameworks and monomeric units into more traditional studies of peptide and protein structure-activity relationships. D-amino acids, N-alkyl amino acids, and related modifications of α-amino acids have long been used to probe conformation and enhance activity of synthetic peptides. In a similar manner, the conformational effects of substituting a β-amino acid for an α-amino acid in peptide secondary structures are now becoming more predictable, so one might see increased use of “β-amino acid scans”133,134 of native peptide sequences.

Nearly ten years ago, Gellman made the suggestion that “realization of the potential of folding polymers may be limited more by the human imagination than by physical barriers”4. As such, we must realize that these structures are not just duplicates of the natural world, but distinct, and we should capitalize on that distinction. Just as the regular spacing of α-amino acids may facilitate formation of a handful of regular secondary structures that mediate some interactions better than others, so too should each foldamer backbone show its strengths in different ways. Clearly, we are only beginning to explore the conformational space of secondary structures available to various backbones. In considering new backbones it will be increasingly important to consider the ease of synthesis of the monomers and oligomers, the ability to control the structure and dynamics of the foldamer, and the ease of structure determination in solution and the solid state. Furthermore, it will be essential to develop new computational methods to assist de novo design of foldamer sequences with predictable structures and activities.

Finally, non-natural oligomers will continue to provide useful systems to test and extend our understanding of how proteins fold into their native three-dimensional structures, and how these structures define their abilities to mediate processes such as catalysis, binding and signal transduction. As one likely outcome of these studies, we can also look forward to the construction of entirely non-natural protein-like tertiary structures, as well as initial forays into functional space. Overall, the recent work reviewed here provides an excellent foundation for the creation of new structures, new functions, and new interfaces with nature. The chemical and biological applications of foldamers are significant, and they will become even more attractive as new frameworks and structural and functional studies are reported.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Chemical Biology website.

References

DeGrado, W.F., Summa, C.M., Pavone, V., Nastri, F. & Lombardi, A. De novo design and structural characterization of proteins and metalloproteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 779–819 (1999).

Baker, D. Prediction and design of macromolecular structures and interactions. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 361, 459–463 (2006).

Alvizo, O., Allen, B.D. & Mayo, S.L. Computational protein design promises to revolutionize protein engineering. Biotechniques 42, 31, 33, 35 passim (2007).

Gellman, S.H. Foldamers: a manifesto. Acc. Chem. Res. 31, 173–180 (1998).

Rueping, M., Mahajan, Y., Sauer, M. & Seebach, D. Cellular uptake studies with β-peptides. ChemBioChem 3, 257–259 (2002).

Potocky, T.B., Menon, A.K. & Gellman, S.H. Cytoplasmic and nuclear delivery of a TAT-derived peptide and a β-peptide after endocytic uptake into HeLa cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 50188–50194 (2003).

Gelman, M.A. et al. Selective binding of TAR RNA by a Tat-derived β-peptide. Org. Lett. 5, 3563–3565 (2003).

Gademann, K., Ernst, M., Hoyer, D. & Seebach, D. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a cyclo-β-tetrapeptide as a somatostatin analogue. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 38, 1223–1226 (1999).

Sadowsky, J.D. et al. Chimeric (α/β + α)-peptide ligands for the BH3-recognition cleft of Bcl-XL: critical role of the molecular scaffold in protein surface recognition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 11966–11968 (2005).

English, E.P., Chumanov, R.S., Gellman, S.H. & Compton, T. Rational development of β-peptide inhibitors of human cytomegalovirus entry. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 2661–2667 (2006).

Kritzer, J.A., Lear, J.D., Hodsdon, M.E. & Schepartz, A. Helical β-peptide inhibitors of the p53-hDM2 interaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 9468–9469 (2004).

Kritzer, J.A., Stephens, O.M., Guarracino, D.A., Reznik, S.K. & Schepartz, A. β-Peptides as inhibitors of protein-protein interactions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 13, 11–16 (2005).

Kritzer, J.A., Hodsdon, M.E. & Schepartz, A. Solution structure of a β-peptide ligand for hDM2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 4118–4119 (2005).

Stephens, O.M. et al. Inhibiting HIV fusion with a β-peptide foldamer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 13126–13127 (2005).

Nunn, C. et al. β(2)/β(3)-di- and α/β(3)-tetrapeptide derivatives as potent agonists at somatostatin sst(4) receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 367, 95–103 (2003).

Werder, M., Hauser, H., Abele, S. & Seebach, D. β-Peptides as inhibitors of small-intestinal cholesterol and fat absorbtion. Helv. Chim. Acta 82, 1774–1783 (1999).

Hamuro, Y., Schneider, J.P. & DeGrado, W.F. De novo design of antibacterial β-peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 12200–12201 (1999).

Porter, E.A., Wang, X., Lee, H.S., Weisblum, B. & Gellman, S.H. Non-haemolytic β-amino-acid oligomers. Nature 404, 565 (2000).

Liu, D. & DeGrado, W. De novo design, synthesis, and characterization of antimicrobial β-peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 7553–7559 (2001).

Epand, R.F., Raguse, T.L., Gellman, S.H. & Epand, R.M. Antimicrobial 14-helical β-peptides: potent bilayer disrupting agents. Biochemistry 43, 9527–9535 (2004).

Epand, R.F. et al. Bacterial species selective toxicity of two isomeric α/β-peptides: role of membrane lipids. Mol. Membr. Biol. 22, 457–469 (2005).

Epand, R.F., Schmitt, M.A., Gellman, S.H. & Epand, R.M. Role of membrane lipids in the mechanism of bacterial species selective toxicity by two α/β-antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1758, 1343–1350 (2006).

Seurynck, S.L., Patch, J.A. & Barron, A.E. Simple, helical peptoid analogs of lung surfactant protein B. Chem. Biol. 12, 77–88 (2005).

Patch, J.A. & Barron, A.E. Helical peptoid mimics of magainin-2 amide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 12092–12093 (2003).

Arvidsson, P.I. et al. Antibiotic and hemolytic activity of a β2/β3 peptide capable of folding into a 12/10-helical secondary structure. ChemBioChem 4, 1345–1347 (2003).

Choi, S. et al. The design and evaluation of heparin-binding foldamers. Angew. Chem. Int. Edn Engl. 44, 6685–6689 (2005).

Cheng, R.P., Gellman, S.H. & DeGrado, W.F. β-Peptides: from structure to function. Chem. Rev. 101, 3219–3232 (2001).

Seebach, D., Hook, D.F. & Glattli, A. Helices and other secondary structures of β- and γ-peptides. Biopolymers 84, 23–37 (2006).

Sharma, G.V.M. et al. A left-handed 9-helix in γ-peptides: synthesis and conformational studies of oligomers with dipeptide repeats of C-linked carbo-γ(4)-amino acids and γ-aminobutyric acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 2944–2947 (2006).

Arndt, H.D., Ziemer, B. & Koert, U. Folding propensity of cyclohexylether-δ-peptides. Org. Lett. 6, 3269–3272 (2004).

Trabocchi, A., Guarna, F. & Guarna, A. γ- and δ-amino acids: synthetic strategies and relevant applications. Curr. Org. Chem. 9, 1127–1153 (2005).

Violette, A. et al. N,N'-linked oligoureas as foldamers: chain length requirements for helix formation in protic solvent investigated by circular dichroism, NMR spectroscopy, and molecular dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 2156–2164 (2005).

Salaun, A., Potel, M., Roisnel, T., Gall, P. & Le Grel, P. Crystal structures of aza-β(3)-peptides, a new class of foldamers relying on a framework of hydrazinoturns. J. Org. Chem. 70, 6499–6502 (2005).

Zega, A. Azapeptides as pharmacological agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 12, 589–597 (2005).

Smith, A.B. III, Knight, S.D., Sprengeler, P.A. & Hirschmann, R. The design and synthesis of 2,5-linked pyrrolinones. A potential non- peptide peptidomimetic scaffold. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 4, 1021–1034 (1996).

Li, X. & Yang, D. Peptides of aminoxy acids as foldamers. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 3367–3379 (2006).

Chakraborty, T.K., Srinivasu, P., Tapadar, S. & Mohan, B.K. Sugar amino acids in designing new molecules. Glycoconj. J. 22, 83–93 (2005).

Claridge, T.D.W. et al. Helix-forming carbohydrate amino acids. J. Org. Chem. 70, 2082–2090 (2005).

Dervan, P.B. Design of sequence-specific DNA-binding molecules. Science 232, 464–471 (1986).

Mathur, P., Ramakumar, S. & Chauhan, V.S. Peptide design using α,β-dehydro amino acids: From β-turns to helical hairpins. Biopolymers 76, 150–161 (2004).

Baldauf, C., Gunther, R. & Hofmann, H.J. Helices in peptoids of α- and β-peptides. Phys. Biol. 3, S1–S9 (2006).

Lee, B.C., Zuckermann, R.N. & Dill, K.A. Folding a nonbiological polymer into a compact multihelical structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 10999–11009 (2005).

Zuckerman, R.N. The chemical synthesis of peptidomimetic libraries. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 3, 580–584 (1993).

Stigers, K.D., Soth, M.J. & Nowick, J.S. Designed molecules that fold to mimic protein secondary structures. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 3, 714–723 (1999).

Yang, X. et al. Backbone-rigidified oligo(m-phenylene ethynylenes). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 3148–3162 (2004).

Kang, S.W., Gothard, C.M., Maitra, S., Wahab, A. & Nowick, J.S. A new class of macrocyclic receptors from iota-peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 1486–1487 (2007).

Fulop, F., Martinek, T.A. & Toth, G.K. Application of alicyclic β-amino acids in peptide chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 35, 323–334 (2006).

Park, J.S., Lee, H.S., Lai, J.R., Kim, B.M. & Gellman, S.H. Accommodation of α-substituted residues in the β-peptide 12-helix: expanding the range of substitution patterns available to a foldamer scaffold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 8539–8545 (2003).

Lelais, G. et al. β-Peptidic secondary structures fortified and enforced by Zn2+ complexation - on the way to β-peptidic zinc fingers? Helv. Chim. Acta 89, 361–403 (2006).

Langenhan, J.M., Guzei, I.A. & Gellman, S.H. Parallel sheet secondary structure in β-peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Edn Engl. 42, 2402–2405 (2003).

Doerksen, R.J., Chen, B., Yuan, J., Winkler, J.D. & Klein, M.L. Novel conformationally-constrained β-peptides characterized by 1H NMR chemical shifts. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2534–2535 (2003).

Gademann, K., Hane, A., Rueping, M., Jaun, B. & Seebach, D. The fourth helical secondary structure of β-peptides: The (P)-2(8)-helix of a β-hexapeptide consisting of (2R,3S)-3-amino-2-hydroxy acid residues. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 1534–1537 (2003).

Arvidsson, P.I., Rueping, L. & Seebach, D. Design, machine synthesis, and NMR-solution structure of a β-heptapetide forming a salt-bridge stabilised 314-helix in methanol and in water. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 649–650 (2001).

Cheng, R.P. & DeGrado, W.F. De novo design of a monomeric helical β-peptide stabilized by electrostatic interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 5162–5163 (2001).

Guarracino, D.A. et al. Relationship between salt-bridge identity and 14-helix stability of β3-peptides in aqueous buffer. Org. Lett. 8, 807–810 (2006).

Hart, S.A., Bahadoor, A.B., Matthews, E.E., Qiu, X.J. & Schepartz, A. Helix macrodipole control of β 3 peptide 14-helix stability in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 4022–4023 (2003).

Rueping, M., Jaun, B. & Seebach, D. NMR structure in methanol of a β-hexapeptide with a disulfide clamp. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2267–2268 (2000).

Vaz, E. & Brunsveld, L. Stable helical, β(3)-peptides in water via covalent bridging of side chains. Org. Lett. 8, 4199–4202 (2006).

Smith, C.K. & Regan, L. Guidelines for protein design: the energetics of β sheet side chain interactions. Science 270, 980–982 (1995).

Kritzer, J.A. et al. Relationship between side chain structure and 14-helix stability of β3-peptides in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 167–178 (2005).

Daniels, D.S., Petersson, E.J., Qiu, J.X. & Schepartz, A. High-resolution structure of a β-peptide bundle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 1532–1533 (2007).

Steiner, T.C.H. C-H···O hydrogen bonding in crystals. Cryst. Rev. 9, 177–228 (2003).

Mathad, R.I., Gessier, F., Seebach, D. & Jaun, B. The effect of backbone-heteroatom substitution on the folding of peptides a single fluorine substituent prevents a β-heptapeptide from folding into a 3(14)-helix (NMR analysis). Helv. Chim. Acta 88, 266–280 (2005).

Pavone, V. et al. β-Alanine containing cyclic peptides with turned structure: the pseudo type II β turn. VI. Biopolymers 34, 1517–1526 (1994).

Karle, I.L., Handa, B.K. & Hassall, C.H. Conformation of cyclic tetrapeptide L-Ser(O-t-Bu)-β-Ala-Gly-L-β-Asp(Ome) containing a 14-membered ring. Acta Crystallogr. B 31, 555–560 (1975).

Chatterjee, S., Roy, R.S. & Balaram, P. Expanding the polypeptide backbone: hydrogen-bonded conformations in hybrid polypeptides containing the higher homologues of α-amino acids. J. R. Soc. Interface (in the press).

Ananda, K. et al. Polypeptide helices in hybrid peptide sequences. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 16668–16674 (2005).

De Pol, S., Zorn, C., Klein, C.D., Zerbe, O. & Reiser, O. Surprisingly stable helical conformations in α/β-peptides by incorporation of cis-β-aminocyclopropane carboxylic acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Edn Engl. 43, 511–514 (2004).

Hayen, A., Schmitt, M.A., Ngassa, F.N., Thomasson, K.A. & Gellman, S.H. Two helical conformations from a single foldamer backbone: “split personality” in short α/β-peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Edn Engl. 43, 505–510 (2004).

Horne, W.S., Price, J.L., Keck, J.L. & Gellman, S.H. Helix bundle quaternary structure from α/β-peptide foldamers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. (in the press).

McNulty, J.C. et al. Electron spin resonance of TOAC labeled peptides: folding transitions and high frequency spectroscopy. Biopolymers 55, 479–485 (2000).

Huston, S.E. & Marshall, G.R. α/3(10)-helix transitions in α-methylalanine homopeptides: conformational transition pathway and potential of mean force. Biopolymers 34, 75–90 (1994).

Schmitt, M.A., Choi, S.H., Guzei, I.A. & Gellman, S.H. Residue requirements for helical folding in short α/β-peptides: crystallographic characterization of the 11-helix in an optimized sequence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 13130–13131 (2005).

Schmitt, M.A., Weisblum, B. & Gellman, S.H. Unexpected relationships between structure and function in α,β-peptides: antimicrobial foldamers with heterogeneous backbones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 6848–6849 (2004).

Sharma, G.V.M. et al. 9/11 mixed helices in α/β peptides derived from C-linked carbo-β-amino acid and L-ala repeats. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 5878–5882 (2005).

Sharma, G.V.M. et al. 12/10- and 11/13-mixed helices in α/γ- and β/γ-hybrid peptides containing C-linked carbo-γ-amino acids with alternating α- and β-amino acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 14657–14668 (2006).

Srinivas, D., Gonnade, R., Ravindranathan, S. & Sanjayan, G.J. A hybrid foldamer with unique architecture from conformationally constrained aliphatic-aromatic amino acid conjugate. Tetrahedron 62, 10141–10146 (2006).

Vasudev, P.G. et al. Hybrid peptide design. Hydrogen bonded conformations in peptides containing the stereochemically constrained γ-amino acid residue, gabapentin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. (in the press).

Huc, I. Aromatic oligoamide foldamers. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 17–29 (2004).

Li, Z.T., Hou, J.L., Li, C. & Yi, H.P. Shape-persistent aromatic amide oligomers: new tools for supramolecular chemistry. Chem. Asian J. 1, 766–778 (2006).

Hamuro, Y., Geib, S.J. & Hamilton, A.D. Oligoanthranilamides; non-peptide subunits that show intramolecular hydrogen bonding control of secondary structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 7529–7541 (1996).

Gong, B. et al. Creating nanocavities of tunable sizes: hollow helices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 11583–11588 (2002).

Dolain, C., Jiang, H., Leger, J.M., Guionneau, P. & Huc, I. Chiral induction in quinoline-derived oligoamide foldamers: assignment of helical handedness and role of steric effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 12943–12951 (2005).

Yi, H.P., Li, C., Hou, J.L., Jiang, X.K. & Li, Z.T. Hydrogen-bonding-induced oligoanthranilamide foldamers. Synthesis, characterization, and complexation for aliphatic ammonium ions. Tetrahedron 61, 7974–7980 (2005).

Hou, J.L. et al. Hydrogen bonded oligohydrazide foldamers and their recognition for saccharides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 12386–12394 (2004).

Li, C. et al. F...H-N hydrogen bonding driven foldamers: efficient receptors for dialkylammonium ions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 5725–5729 (2005).

Berl, V., Huc, I., Khoury, R.G., Krische, M.J. & Lehn, J.M. Interconversion of single and double helices formed from synthetic molecular strands. Nature 407, 720–723 (2000).

Jiang, H., Leger, J.M. & Huc, I. Aromatic δ-peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 3448–3449 (2003).

Kanamori, D., Okamura, T.A., Yamamoto, H. & Ueyama, N. Linear-to-turn conformational switching induced by deprotonation of unsymmetrically linked phenolic oligoamides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 969–972 (2005).

Kolomiets, E. et al. Contraction/extension molecular motion by protonation/deprotonation induced structural switching of pyridine derived oligoamides. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2868–2869 (2003).

Maurizot, V., Dolain, C. & Huc, I. Intramolecular versus intermolecular induction of helical handedness in pyridinedicarboxamide oligomers. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 1293–1301 (2005).

Haldar, D., Jiang, H., Leger, J.M. & Huc, I. Interstrand interactions between side chains in a double-helical foldamer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 5483–5486 (2006).

Doerksen, R.J. et al. Controlling the conformation of arylamides: computational studies of intramolecular hydrogen bonds between amides and ethers or thioethers. Chem. Eur. J. 10, 5008–5016 (2004).

Tang, H., Doerksen, R.J., Jones, T.V., Klein, M.L. & Tew, G.N. Biomimetic facially amphiphilic antibacterial oligomers with conformationally stiff backbones. Chem. Biol. 13, 427–435 (2006).

Rodriguez, J.M. & Hamilton, A.D. Intramolecular hydrogen bonding allows simple enaminones to structurally mimic the i, i+4, and i+7 residues of an α-helix. Tetrahedr. Lett. 47, 7443–7446 (2006).

Estroff, L.A., Incarvito, C.D. & Hamilton, A.D. Design of a synthetic foldamer that modifies the growth of calcite crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 2–3 (2004).

Jiang, H., Maurizot, V. & Huc, I. Double versus single helical structures of oligopyridine-dicarboxamide strands. Part 1: effect of oligomer length. Tetrahedron 60, 10029–10038 (2004).

Eldred, S.E. et al. Effects of side chain configuration and backbone spacing on the gene delivery properties of lysine-derived cationic polymers. Bioconjug. Chem. 16, 694–699 (2005).

Seebach, D., Beck, A.K. & Bierbaum, D.J. The world of β- and γ-peptides comprised of homologated proteinogenic amino acids and other components. Chem. Biodivers. 1, 1111–1239 (2004).

Geueke, B. et al. Bacterial cell penetration by β(3)-oligohomoarginines: Indications for passive transfer through the lipid bilayer. ChemBioChem 6, 982–985 (2005).

Porter, E.A., Weisblum, B. & Gellman, S.H. Use of parallel synthesis to probe structure-activity relationships among 12-helical β-peptides: evidence of a limit on antimicrobial activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 11516–11529 (2005).

Arvidsson, P.I. et al. Exploring the antibacterial and hemolytic activity of shorter- and longer-chain β-, α,β-, and γ-peptides, and of β-peptides from β2–3-aza- and β3–2-methylidene-amino acids bearing proteinogenic side chains–a survey. Chem. Biodivers. 2, 401–420 (2005).

Zasloff, M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415, 389–395 (2002).

Schmitt, M.A., Weisblum, B. & Gellman, S.H. Interplay among folding, sequence, and lipophilicity in the antibacterial and hemolytic activities of α/β-peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 417–428 (2007).

Kuroda, K. & DeGrado, W.F. Amphiphilic polymethacrylate derivatives as antimicrobial agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 4128–4129 (2005).

Ivanov, I. et al. Characterization of nonbiological antimicrobial polymers in aqueous solution and at water-lipid interfaces from all-atom molecular dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 1778–1779 (2006).

Murray, J.K. et al. Efficient synthesis of a β-peptide combinatorial library with microwave irradiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 13271–13280 (2005).

Knight, S.M., Umezawa, N., Lee, H.S., Gellman, S.H. & Kay, B.K. A fluorescence polarization assay for the identification of inhibitors of the p53–DM2 protein-protein interaction. Anal. Biochem. 300, 230–236 (2002).

Kritzer, J.A., Luedtke, N.W., Harker, E.A. & Schepartz, A. A rapid library screen for tailoring β-peptide structure and function. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 14584–14585 (2005).

Sadowsky, J.D. et al. (α/β+α)-Peptide antagonists of BH3 Domain/Bcl-x(L) recognition: toward general strategies for foldamer-based inhibition of protein-protein interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 139–154 (2007).

Martinek, T.A. et al. Secondary structure dependent self-assembly of β-peptides into nanosized fibrils and membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 2396–2400 (2006).

Pomerantz, W.C., Abbott, N.L. & Gellman, S.H. Lyotropic liquid crystals from designed helical β-peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 8730–8731 (2006).

Arnt, L. & Tew, G.N. New poly(phenyleneethynylene)s with cationic, facially amphiphilic structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 7664–7665 (2002).

Liu, D. et al. Nontoxic membrane-active antimicrobial arylamide oligomers. Angew. Chem. Int. Edn Engl. 43, 1158–1162 (2004).

Tew, G.N. et al. De novo design of biomimetic antimicrobial polymers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 5110–5114 (2002).

Hill, D.J., Mio, M.J., Prince, R.B., Hughes, T.S. & Moore, J.S. A field guide to foldamers. Chem. Rev. 101, 3893–4012 (2001).

Arnt, L. & Tew, G.N. Cationic facially amphiphilic poly(phenylene ethynylene)s studied at the air-water interface. Langmuir 19, 2404–2408 (2003).

Tew, G.N., Clements, D., Tang, H., Arnt, L. & Scott, R.W. Antimicrobial activity of an abiotic host defense peptide mimic. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1758, 1387–1392 (2006).

Arnt, L., Rennie, J.R., Linser, S., Willumeit, R. & Tew, G.N. Membrane activity of biomimetic facially amphiphilic antibiotics. J. Phys. Chem. B Condens. Matter Mater. Surf. Interfaces Biophys. 110, 3527–3532 (2006).

Chen, X. et al. Observing a molecular knife at work. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 2711–2714 (2006).

Lopez, C., Nielsen, S. & Srinivas, G. Probing membrane insertion activity of antimicrobial polymers via coarse-grain molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comp. 2, 649–655 (2006).

Chen, L. et al. p53 α-helix mimetics antagonize p53/MDM2 interaction and activate p53. Mol. Cancer Ther. 4, 1019–1025 (2005).

Ernst, J.T., Becerril, J., Park, H.S., Yin, H. & Hamilton, A.D. Design and application of an α-helix-mimetic scaffold based on an oligoamide-foldamer strategy: antagonism of the bak BH3/Bcl-xL complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 535–539 (2003).

Yin, H. et al. Terephthalamide derivatives as mimetics of helical peptides: disruption of the Bcl-x(L)/Bak interaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 5463–5468 (2005).

Yin, H., Frederick, K.K., Liu, D., Wand, A.J. & DeGrado, W.F. Arylamide derivatives as peptidomimetic inhibitors of calmodulin. Org. Lett. 8, 223–225 (2006).

Cheng, R.P. & DeGrado, W.F. Long-range interactions stabilize the fold of a non-natural oligomer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 11564–11565 (2002).

Chakraborty, P. & Diederichsen, U. Three-dimensional organization of helices: design principles for nucleobase-functionalized β-peptides. Chem. Eur. J. 11, 3207–3216 (2005).

Raguse, T.L., Lai, J.R., LePlae, P.R. & Gellman, S.H. Toward β-peptide tertiary structure: self-association of an amphiphilic 14-helix in aqueous solution. Org. Lett. 3, 3963–3966 (2001).

Qiu, J.X., Petersson, E.J., Matthews, E.E. & Schepartz, A. Toward β-amino acid proteins: a cooperatively folded β-peptide quaternary structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 11338–11339 (2006).

Seebach, D., Ciceri, P.E., Overhand, M., Jaun, B. & Rigo, D. Probing the helical secondary structure of short-chain β-peptides. Helv. Chim. Acta 79, 2043–2066 (1996).

Appella, D.H., Christianson, L.A., Karle, I.L., Powell, D.R. & Gellman, S.H. β-peptide foldamers: robust helix formation in a new family of β-amino acid oligomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 13071–13072 (1996).

Appella, D.H. et al. Residue-based control of helix shape in β-peptide oligomers. Nature 387, 381–384 (1997).

Guichard, G. et al. Melanoma peptide MART-1(27–35) analogues with enhanced binding capacity to the human class I histocompatibility molecule HLA-A2 by introduction of a β-amino acid residue: implications for recognition by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J. Med. Chem. 43, 3803–3808 (2000).

Webb, A.I. et al. T cell determinants incorporating β-amino acid residues are protease resistant and remain immunogenic in vivo. J. Immunol. 175, 3810–3818 (2005).

Gesell, J., Zasloff, M. & Opella, S.J. Two-dimensional 1H NMR experiments show that the 23-residue magainin antibiotic peptide is an α-helix in dodecylphosphocholine micelles, sodium dodecylsulfate micelles, and trifluoroethanol/water solution. J. Biomol. NMR 9, 127–135 (1997).

Nusslein, K., Arnt, L., Rennie, J., Owens, C. & Tew, G.N. Broad-spectrum antibacterial activity by a novel abiogenic peptide mimic. Microbiology 152, 1913–1918 (2006).

Schmitt, M.A., Choi, S.H., Guzei, I.A. & Gellman, S.H. New helical foldamers: heterogeneous backbones with 1: 2 and 2: 1 α:β-amino acid residue patterns. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 4538–4539 (2006).

Claridge, T.D.W. et al. 10-Helical conformations in oxetane [β]-amino acid hexamers. Tetrahedr. Lett. 42, 4251–4255 (2001).

Hetenyi, A., Mandity, I.M., Martinek, T.A., Toth, G.K. & Fulop, F. Chain-length-dependent helical motifs and self-association of β-peptides with constrained side chains. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 547–553 (2005).

Aravinda, S., Ananda, K., Shamala, N. & Balaram, P. α-γ hybrid peptides that contain the conformationally constrained gabapentin residue: characterization of mimetics of chain reversals. Chemistry (Easton) 9, 4789–4795 (2003).

Arvidsson, P.I., Frackenpohl, J. & Seebach, D. Syntheses and CD-spectroscopic investigations of longer-chain β-peptides: preparation by solid-phase couplings of single amino acids, dipeptides, and tripeptides. Helv. Chim. Acta 86, 1522–1553 (2003).

Murray, J.K. & Gellman, S.H. Application of microwave irradiation to the synthesis of 14-helical β-peptides. Org. Lett. 7, 1517–1520 (2005).

Carrillo, N., Davalos, E.A., Russak, J.A. & Bode, J.W. Iterative, aqueous synthesis of β(3)-oligopeptides without coupling reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 1452–1453 (2006).

Murakami, H., Ohta, A., Ashigai, H. & Suga, H. A highly flexible tRNA acylation method for non-natural potypeptide synthesis. Nat. Methods 3, 357–359 (2006).

Josephson, K., Hartman, M.C.T. & Szostak, J.W. Ribosomal synthesis of unnatural peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 11727–11735 (2005).

Hartman, M.C.T., Josephson, K. & Szostak, J.W. Enzymatic aminoacylation of tRNA with unnatural amino acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 4356–4361 (2006).

Yoo, B. & Kirshenbaum, K. Protease-mediated ligation of abiotic oligomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 17132–17133 (2005).

Glattli, A. & van Gunsteren, W.F. Are NMR-derived model structures for β-peptides representative for the ensemble of structures adopted in solution? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 6312–6316 (2004).

Trzesniak, D., Glattli, A., Jaun, B. & van Gunsteren, W.F. Interpreting NMR data for β-peptides using molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 14320–14329 (2005).

Applequist, J., Bode, K.A., Appella, D.H., Christianson, L.A. & Gellman, S.A. Theorectical and experimental circular dichroic spectra of the novel helical foldamer poly[(1R,2R)-trans-2-aminocyclopentanecarboxylic acid]. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 4891–4892 (1998).

Glattli, A., Daura, X., Seebach, D. & van Gunsteren, W.F. Can one derive the conformational preference of a β-peptide from its CD spectrum? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 12972–12978 (2002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

W. DeGrado is named on patents for antimicrobial and antiheparin foldamers. These patents are held by the University of Pennsylvania and licensed to PolyMedix.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Fig. 1

Model of the interaction between a designed arylamide (smMLCK mimic) and calmodulin. (PDF 56 kb)

Supplementary Table 1

Interactions of non-natural foldamers with biological targets. (PDF 57 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goodman, C., Choi, S., Shandler, S. et al. Foldamers as versatile frameworks for the design and evolution of function. Nat Chem Biol 3, 252–262 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio876

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio876

This article is cited by

-

Synthesis of a glycan hairpin

Nature Chemistry (2023)

-

Foldamers reveal and validate therapeutic targets associated with toxic α-synuclein self-assembly

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Deciphering the conformational landscape of few selected aromatic noncoded amino acids (NCAAs) for applications in rational design of peptide therapeutics

Amino Acids (2022)

-

Improving coarse-grained models of protein folding through weighting of polar-polar/hydrophobic-hydrophobic interactions into crowded spaces

Journal of Molecular Modeling (2022)

-

The folding propensity of α/sulfono-γ-AA peptidic foldamers with both left- and right-handedness

Communications Chemistry (2021)