Abstract

Analysis of gene expression patterns in normal tissues and their perturbations in tumours can help to identify the functional roles of oncogenes or tumour suppressors and identify potential new therapeutic targets. Here, gene expression correlation networks were derived from 92 normal human lung samples and patient-matched adenocarcinomas. The networks from normal lung show that NKX2-1 is linked to the alveolar type 2 lineage, and identify PEBP4 as a novel marker expressed in alveolar type 2 cells. Differential correlation analysis shows that the NKX2-1 network in tumours includes pathways associated with glutamate metabolism, and identifies Vaccinia-related kinase (VRK1) as a potential drug target in a tumour-specific mitotic network. We show that VRK1 inhibition cooperates with inhibition of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase signalling to inhibit growth of lung tumour cells. Targeting of genes that are recruited into tumour mitotic networks may provide a wider therapeutic window than that seen by inhibition of known mitotic genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer death in women and men in the United States, taking more lives each year than breast, prostate and colorectal cancers combined1. Despite major advances in our knowledge of lung cancer genetics, the 5-year survival rate for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients is around 16% (ref. 2). Lung cancer treatment is therefore moving rapidly towards an era of personalized medicine, where the molecular characteristics of a patient’s tumour will dictate the optimal treatment modalities. NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations show significantly improved responses to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, for example, gefitinib or erlotinib that target this receptor kinase3. However, almost all of these patients eventually relapse due to rewiring of the genetic architecture of the tumours, either through secondary EGFR mutations, or other unknown genetic alterations4. This paradigm of tumour rewiring in the face of targeted treatment is evident from many clinical trials that have been reported or are in progress, suggesting that novel approaches to the identification of drug targets and/or methods for analysis of the rewiring process to find complementary targets, will be necessary to improve survival and the probability of long-term cures.

We have previously shown that genetic analysis of gene expression can provide a network view of the molecular architecture of normal mouse skin5, and of the changes in this architecture associated with transformation to carcinoma6. This approach allowed us to identify networks that control normal skin cellular components, such as the hair follicles, muscle, and inflammatory cells, as well as the changes in these networks that accompany development of carcinomas. We have applied the same strategy to analysis of normal human lung, and matched lung adenocarcinomas from the same patients. The networks generated from a panel of 92 matched normal-tumour lung samples contain motifs representing major cell structural and functional components of the lung, as well as changes in mitotic and inflammation-associated networks in carcinomas. The availability of matched adenocarcinoma tissue from each patient enabled us to generate a coordinated network of genes that are up- or downregulated in tumours compared with the normal tissue from the same individuals. This ‘progression network’ revealed important contributions from stromal and infiltrating inflammatory cells due to influx of host cells into the tumour microenvironment, but also revealed tumour-specific changes in the cell cycle and mitotic networks that were exploited to identify VRK1 (Vaccinia-related kinase 1) as a mitotic target for the tumour cell cycle.

Results

Gene expression networks in normal lung

Sets of genes that exhibit correlated expression patterns in normal tissue from a genetically heterogeneous population often share a common function or are part of the same physical structure5,7,8. We first carried out gene expression network analysis of 92 samples of normal unaffected human lung samples from lung cancer patients. Although previous studies of normal mouse skin clearly identified both structural and functional components of this tissue5, application of the same approach to normal human lung identified a large number of significant correlations that were not readily resolved into similar motifs (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Adenocarcinomas share many characteristics with cells of the normal alveolar type 2 lineage, for which the best characterized markers are the genes encoding the surfactant proteins such as SFTPB. We therefore constructed a targeted gene expression network for SFTA2 and SFTPB and the transcription factor NKX2-1 from the normal lung samples, and noted that several surfactant proteins (SFTPA1B, SFTPA2B, SFTA3) and other alveolar type 2 markers (for example, LAMP3) are represented in this correlation network (Fig. 1a).

(a) Gene coexpression networks associated with surfactant protein markers and NKX2-1 in normal human lung tissues. Gene pairs that are significantly correlated are drawn as blue boxes connected by a line; PEBP4 is shown in yellow. Other type 2 pneumocyte markers are shown in orange. (b) Adjacent sections of three normal slides from different lung cancer patients (1101N, 1116N and 1137N) were stained for expression of SFTPD, SFTPB, PEBP4 protein and a negative control (−) (microscope magnification: × 100). Type 2 pneumocytes were stained for known markers SFTPD and SFTPB as well as PEBP4, which was identified as a candidate marker for type 2 pneumocytes in gene expression networks. These slides indicate that the same cells express both surfactant proteins and PEBP4 protein.

NKX2-1 has previously been reported to be a lineage-specific oncogene that is amplified in a subset of NSCLC, in particular in adenocarcinomas9,10. Others have demonstrated by immunohistochemistry that the NKX2-1 protein is also mainly expressed in alveolar type 2 cells11,12. A functional association of NKX2-1 with surfactant protein genes is supported by the observation that mutation of NKX2-1 results in interstitial lung disease in Brain-Lung-Thyroid Syndrome by surfactant protein promoter dysregulation13. Abnormal function of NKX2-1 also affects respiratory distress syndrome of the newborn14. Taken together, these data support a role for NKX2-1 in type 2 pneumocyte lineage determination both in normal lung and in lung adenocarcinomas9,10.

While many of the genes in these networks are known markers of their respective lineages, this approach has the potential to identify completely novel markers for specific cell types within the lung and other tissues. We validated the network approach for identification of markers for alveolar type 2 cells using antibodies to PEBP4, a RAF kinase inhibitory protein family member and a scaffold protein controlling myoblast and muscle cell differentiation through MEK and ERK signalling15. This protein has not previously been associated with alveolar type 2 cells, but was significantly coexpressed with surfactant protein genes in normal human lungs. Immunohistochemical staining was carried out on normal human lung sections using antibodies specific for PEBP4 and two other type 2 pneumocyte markers, SFTPB and SFTPD. The results shown in Fig. 1b demonstrate that PEBP4 protein is localized in the same cell population as the known type 2 markers, thus providing support for the predictions made by the gene expression networks.

Rewiring of gene expression networks in lung tumours

Correlation analysis of lung tumours from the same patients revealed several major motifs representing cell growth and mitosis, inflammatory responses and stromal cells (Fig. 2a). In contrast to the normal lung network, the tumour gene expression correlations identified clear modules representing structural (Clara cells) and functional (inflammation, mitosis, translation) components in lung adenocarcinomas. We then produced a molecular view of the perturbations in gene expression between these normal lung tissues and matched adenocarcinomas by combining differential expression and correlation to identify functionally related sets of genes that are coordinately modified during tumorigenesis6. This ‘progression network’ (Fig. 2b) was produced by subtracting gene expression results in patient’s normal samples from the corresponding adenocarcinoma samples to produce a fold-change value for each gene (see Methods). We then identified gene pairs, which were significantly correlated in their fold-change and significantly up- or downregulated.

(A) Significantly correlated gene pairs that were part of a three-gene clique were plotted (r≥+/−0.75). This analysis identified network motifs associated with mitosis, protein translation, stromal cells/invasion, inflammation and Clara cells. (B) Progression network of lung adenocarcinoma. Gene pairs with significantly correlated change (r≥+/−0.7) and significant change in mRNA gene expression level between normal lung and adenocarcinomas are drawn as nodes (false discovery rate<5%, fold-change≥2). Red nodes indicate increased expression and green nodes indicate decreased expression, with darker colour indicating more extreme change. Grey lines connect genes with significant direct correlated change and red lines indicate inverse correlation. a, Clara cell and collagen motifs; b, cell cycle motif; c, type II pneumocyte motif.

The progression network identified numerous structural and functional features of the normal lung that were altered either positively or negatively in matched lung tumours from the same patients. Motifs significantly enriched for genes with roles in mitosis, translation, tumour–stromal interactions and immune responses were significantly upregulated in matched tumours compared with normal tissue. The collagen and stromal gene motif contained genes, such as Fibroblast activation protein (FAP) and fibronectin type III domain containing 1 (FNDC1), which are associated with epithelial tumour growth16,17. Motifs associated with negative regulation of cell proliferation, cell adhesion and focal adhesion assembly were coordinately downregulated. Consistent with the morphological changes that occur during tumorigenesis, the networks corresponding to the alveolar type 2 cells (surfactant protein genes) and Clara cells (secretoglobins CC-10 or SCG1A1) formed distinct cliques that were significantly downregulated in cancers.

Type 2 pneumocyte network rewiring in lung adenocarcinomas

NKX2-1 is significantly correlated with surfactant protein gene expression in tumours (Fig. 3), supporting a model whereby NKX2-1 maintains a role in determination of the alveolar type 2 cell lineage. However, the NKX2-1 tumour correlation network provides evidence for significant rewiring of the NKX2-1 gene network associated with transformation. Although several components of the normal NKX2-1 network including surfactant protein genes were also significantly correlated with NKX2-1 in tumours, the tumour network included many genes significantly correlated in tumours that showed minimal association with NKX2-1 expression levels in normal lungs (see Methods and Table 1). Five of the 23 genes in this set are involved in the glutamine biosynthetic process (glutaminase 2: GLS2; gamma-glutamyl carboxylase: GGCX; gamma-glutamyltransferase 1: GGT1; gamma-glutamyltransferase 2: GGT2; Gamma-glutamyltransferase light chain 1: GGTLC1). This gene set is significantly enriched for genes with roles in glutathione metabolism and glutamate secretion (corrected P-value <2.4 × 10−3, hypergeometric test). Glutamine metabolism is increased in cancer cells and has been linked to the Warburg effect associated with Myc deregulation18. These data indicate that the NKX2-1 transcription factor pathway is substantially rewired in lung adenocarcinoma cells, and is now associated with pathways that are required for rapid cell growth and the metabolic requirements of cancer cells. The availability of small-molecule inhibitors of GLS2 (ref. 19) may provide a possible therapeutic approach to exploitation of this rewired network for treatment of adenocarcinomas that overexpress NKX2-1.

Gene coexpression networks associated with surfactant protein markers and NKX2-1 in human lung adenocarcinomas. The NKX2-1 network in tumours shows coexpression with genes relevant to tumour susceptibility (for example, CLPTM1L) and tumour metabolism (for example, GLS2, GGT2, GGTLC1, GGCX, GPD1L) that correlated at lower levels in the comparable normal lung network (coloured in pink). Grey lines connect genes with significant direct correlation and red lines indicate inverse correlation.

Several additional genes not associated with normal type 2 pneumocytes were also linked to NKX2-1 in this network (Fig. 3). One of these genes, CLPTM1L (CLPTM1-like) has been identified from genome-wide association studies as a candidate susceptibility gene for lung cancer20,21,22. CLPTM1L is physically located on chromosome 5p15 in close proximity to TERT, which is another strong candidate susceptibility gene in the region. Although the known functions of TERT in control of telomere length, as well as its other functions in growth control23,24, make it a prime candidate, the strong coregulation of CLPTM1L with a gene known to have an important role in adenocarcinoma lineage commitment suggests that it may also be involved in lung cancer susceptibility.

VRK1 as a drug target in adenocarcinoma mitotic networks

The most strongly upregulated motif in the adenocarcinoma progression network was significantly enriched for genes active in the M-phase of the mitotic cycle (corrected P=6.4 × 10−15) (Fig. 2b). This network comprises many genes that are attractive drug targets for cancer therapy, including the kinases AURKA, AURKB, CCNB2, TTK, MELK and PLK4 (25,26,27,28,29,30). Inhibitors of several of these kinases are presently being tested in clinical trials, however their essential roles in normal mitosis may preclude development as cancer therapeutics because of the toxicity that would be expected owing to inhibition of dividing cells in the bone marrow, colon and other proliferative tissues. A major goal of this study was to use network analysis to identify ‘druggable’ target genes that may function selectively in tumour as compared with normal lung tissue. As the cell cycle has been a rich source of cancer drug targets, we carried out network analysis of AURKA and CCNB2, both well-known cell cycle genes, in both normal lung and tumour samples. Although a number of kinases exhibited significant correlations (r>0.6) in gene expression with AURKA and CCNB2 in both normal and tumour tissue, CDC2 and VRK1 showed a clear cell cycle network that was specific for lung cancers. (Supplementary Fig. S2).

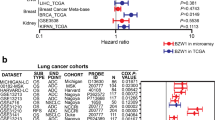

We decided to focus our functional studies on one of these targets, VRK1, which is a serine/threonine protein kinase originally characterized through homology to a Vaccinia-related kinase31. Subsequent work determined that VRK1 phosphorylates the MDM2-binding site of TP53 (32) and is in turn downregulated by wild-type TP5333 but not mutant TP5334. Ablation of VRK1 in vitro blocks cell cycle progression at G135. In normal lung tissue, VRK1 expression is significantly correlated with a wide spectrum of different genes, possibly reflecting the diverse roles of this kinase in normal tissues, but this list is not significantly enriched in genes that control the cell cycle. In contrast, in the lung adenocarcinoma network shown in Fig. 2a, VRK1 is significantly correlated with the mitotic cell cycle gene network (corrected P-value for enrichment: 5 × 10−15; Fig. 4a). In contrast, no association with mitosis was found for VRK1 in normal lung gene expression networks (Supplementary Fig. S1). Although VRK1 gene expression is frequently upregulated in tumours compared with matched normal lung samples, the mean change in gene expression elevation at the RNA level was relatively modest (less than twofold) and substantially less than that seen for other known mitotic genes, such as Aurora kinases and Cyclin B2 (Fig. 4b). For this reason, VRK1 did not appear in the progression network shown in Fig. 2b, which only shows genes that show the strongest upregulation in tumours compared with matched normal tissue.

(a) Gene pairs that are significantly correlated with VRK1 (highlighted in yellow) are drawn as in Fig. 4. This network is significantly enriched for genes that function in the M-phase of mitosis. (b) mRNA gene expression of VRK1, AURKA and CCNB2 in normal lung and matched tumour tissues. Box plot displaying fold-change values for matched lung adenocarcinoma and normal lung tissue for three genes: VRK1, Aurora Kinase A (AURKA) and Cyclin B 2 (CCNB2). The mean increase in gene expression between normal and matched tumour samples is smaller in VRK1 than in AURKA and CCNB2.

One possible explanation for the lack of association to mitosis in normal lung is that relatively few cells in normal lung are actually cycling. We therefore investigated the correlations for Vrk1 in an independent data set derived from mouse skin, which is a proliferative self-renewing tissue5. No significant enrichment for Vrk1 correlations with mitosis genes was found in these normal tissues by BiNGO analysis (Supplementary Fig. S3a), although previous analysis has clearly shown the presence of a strong normal mitotic network5. In contrast, significant numbers of mitosis-related genes correlating with VRK1 were seen in tumour gene expression data sets from mouse carcinomas (Supplementary Fig. S3b), and in an independent set of human lung tumours36 and two human breast tumour data sets37,38 (data not shown).

As VRK1 has previously been implicated in p53 signalling and DNA damage responses33,34, we calculated the correlation between VRK1 and all other genes separately in adenocarcinomas with a wild-type TP53 gene (N=54) and those with mutant TP53 (N=23). We identified genes significantly correlated with VRK1 in TP53 wild-type (WT) but not TP53 mutant tumours, requiring a change in r statistic of at least 0.5. Of the nine genes matching these criteria, several are involved in DNA damage responses, including X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 3 (XRCC3), a RAD51 family member involved in double-strand break repair, FKBP3, an MDM2-interacting protein that contributes to TP53 regulation39, and CDC25A, a key cell cycle checkpoint gene inhibited when TP53 is activated during the DNA damage response40. This provides supporting evidence that VRK1 influences the TP53 DNA damage response pathway, but this influence is ablated in tumours where TP53 has been mutated. We also performed EGFR and K-ras mutation screening and divided samples into mutant and wildtype for gene expression network analysis. There was no significantly different network based on either EGFR or K-ras mutation status, due to the small numbers of samples in each subset and the relative heterogeneity of tumours within a subset.

VRK1 colocalizes with cell cycle markers

Three lung cancer cell lines (A549, H1299 and H460) were transfected with vectors encoding VRK1 short hairpin RNA (shRNA), and immunofluorescence (IF) staining was used to verify correlation of VRK1 expression with cell cycle markers such as Ki-67 and CDC2. Ki-67 is a well-known proliferation marker and CDC2 (CDK1) is a critical kinase involved in the G2/M phase of cell cycle progression. VRK1 and Ki-67 showed mainly nuclear staining in two lung cancer cell lines tested (A549 and H460) (Fig. 5a). Downregulation of VRK1 using shRNA in both cell lines led to depletion of nuclear staining for both Ki-67 and VRK1, with residual staining mainly in the cytoplasm or nuclear membrane. CDC2, which was correlated in gene expression with VRK1 in the tumour networks, showed both cytoplasmic and nuclear staining in A549 and H1299 and mainly nuclear staining in H460 (Fig. 5c–e). CDC2 expression was colocalized with VRK1 and was reduced in VRK1 shRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 5c–e). These data show that VRK1 correlates with CDC2 at both mRNA and protein levels.

(a,b) VRK1 and K-67 was also costained with different fluorescent dyes (VRK1, green; Ki-67, red) in vector and VRK1 shRNA-transfected cells. After shRNA knockdown of VRK1 in cell lines (A549 and H460), both VRK1 and KI-67 expression was significantly reduced. (c–e) VRK1 (green) and CDC2 (red) were costained in three lung cancer cell lines (A549, H460 and H1299). VRK1 and CDC2 were found to be mainly colocalized in VRK1 shRNA cell lines.Mouse monoclonal VRK1 antibody (1F6) was used for panels a–e. Scale bar, 50 μm.

We also checked the protein expression levels of VRK1 and CDC2 in normal lung and matched tumour tissue slides by immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Supplementary Fig. S4). VRK1 showed weak staining in mainly bronchioles and was very weak in other regions of normal lung, while it exhibited very strong staining in certain regions of tumours (Supplementary Fig. S4). Although VRK1 mRNA expression increased by only ~1.5–2 fold in lung tumours compared with normal lung (Fig. 4), VRK1 protein levels were strongly increased in lung tumours (Supplementary Fig. S4). Staining patterns observed for CDC2 were similar to patterns for VRK1 in both normal and matched tumour slides (Supplementary Fig. S4). While bronchiole regions showed only weak but recognizable staining in normal lung slides, most of the tumours were stained by antibodies against CDC2.

Combined VRK1 and PARP inhibition alters lung cancer growth

We designed shRNA probes to downregulate VRK1 expression and transfected them into lung cancer cell lines. After verifying that the shRNAs induced a significant VRK1 expression reduction (Fig. 6a), flow cytometry/PI staining was done in vector and VRK1 shRNA-transfected lung cancer cells. G1 arrest was observed in VRK1 shRNA-transfected H460 lung cancer cell line, whereas normal cell cycle progression was observed in vector-transfected H460 (Student’s t-test, P<0.0001, Fig. 6b). Similar results were obtained with another lung cancer cell line H1299 (Fig. 6b). VRK1 has previously been shown to have a TP53-mediated role in DNA damage repair, and VRK1 gene expression is positively correlated with BRCA1 in lung tumours (correlation r=0.59). Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors are novel anti-cancer drugs that are presently in clinical trials for treatment of breast cancers carrying BRCA1 mutations41. PARP inhibitors have been used for ovarian, breast and prostate cancer but not in lung cancers. Thus, we checked whether VRK1 shRNA-transfected cells may be sensitized to treatment with PARP inhibitors (ABT-888). Significantly increased sensitivity to PARP inhibitor was observed only in VRK1 shRNA cells compared with vector-transfected cells (Fig. 6c). Around a 40% decrease of cell viability was observed after ABT-888 treatment of control cells compared with dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) treatment, but a 70% decrease in cell viability was shown after ABT-888 treatment of the VRK1 shRNA cell line (Student’s t-test, P=0.001; Fig. 6c). This suggests that VRK1 could be a viable therapeutic target in lung cancer patients, especially in combination with PARP inhibitors. A colony-formation assay was done in H1299 lung cancer cell line with VRK1 shRNA and a control vector transfection. A significant reduction of colony number was identified in VRK1 shRNA-transfected cells after PARP inhibitor (ABT-888) treatment (Fig. 6d). ABT-888 treatment results in two additional lung cancer cell lines (H2170 and A549) with VRK1 shRNA are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5.

(a) Lung cancer cell lines (H460 and H1299) were analysed by immunoblot assay to measure VRK1 protein levels after vector and VRK1 shRNA transfection. Reduced protein expression of VRK1 was observed in VRK1 shRNA cell lines. (b) The same cell lines were used for FACS analysis to check cell cycle status. While normal cell cycle progression was found in vector-transfected cells, G1 arrest was observed in VRK1 shRNA-transfected H460 cells (P<0.0001) and H1299 cells (P=0.03). Experiments were carried out three times independently. V, vector-transfected cell lines; VRK1sh, VRK1 shRNA-transfected cell line. (c) Vector and VRK1 shRNA-transfected H1299 cell lines were treated with PARP inhibitor (ABT-888, 20 μM) and DMSO to measure cell viability. A synergistic increase in sensitivity (decreased cell viability) was observed in PARP inhibitor-treated VRK1 shRNA cell lines compared with vector-transfected cells (P=0.001). Experiments were done three times independently. The data are represented as the mean±s.d. (d) A colony-formation assay was done in H1299 lung cancer cell line with VRK1 shRNA and control vector transfection. H1299 cells (2,400 cells per well in the left and 600 cells per well in the right panel) were treated with ABT-888 (PARP inhibitor, 20 μM) in serum-free medium for 48 h. Regular medium was then given to cells after two times washing with PBS. After a week in regular medium, each plate was fixed with 100% methanol and stained with a 0.25% crystal violet staining solution. All experiments were done in triplicate. A synergistic reduction in colony number was identified in VRK1 shRNA-transfected cells treated with the PARP inhibitor (P=0.003 for 2,400 cells and P=0.003 for 600 cells per well). The P-values were calculated using Student’s t-test.

To check the effect of VRK1 in normal lung cell lines, we transfected VRK1shRNA and a control vector into MRC-5 (normal human fetal lung fibroblasts) and BEAS-2B (normal human lung epithelial cells immortalized with an adenovirus 12-SV40 virus hybrid (Ad12SV40)). There was no effect of VRK1 downregulation on growth of the MRC-5 cells (Student’s t-test, P=0.64), although treatment with ABT-888 (PARP inhibitor, 20 μM) in both VRK1 shRNA and control vector-transfected cells reduced cell growth. There was no synergistic effect of VRK1 downregulation and PARP inhibition (ABT-888 20 μM) in both MRC-5 (Student’s t-test, P=0.45) and BEAS-2B (Student’s t-test, P=0.142) cells, which supports our tumour-specific VRK1 mitotic network data. We selected two genes, Gli1 (control) and AURKA (a known mitotic cycle gene), to test the possibility that downregulation of any cell cycle gene may act together with PARP inhibition to reduce cell viability. Short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) for Gli1, AURKA, VRK1 or a scrambled control siRNA (Qiagen) were transfected into H2170 lung cancer cell line. ABT-888 (20 μM) was added to the cell line 24 h after siRNA transfection and measured for cell viability using CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay kit (Promega). No significant additive or synergistic effect of PARP inhibition and siRNA-mediated downregulation of Gli1 or AURKA was observed, while VRK1 siRNA treatment showed a significant cell viability decrease with PARP inhibition (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Discussion

Lung cancer is projected to increase substantially in the future due to the continued expansion of smoking habits particularly in Asia42. Substantial advances have been made in development of targeted treatments for lung cancers, in particular through the availability of inhibitors of EGFR (Cetuximab, Tarceva). These drugs have been used successfully for treatment of lung cancers carrying activating mutations in the EGFR kinase3, but a consistent effect on long-term survival has remained elusive, and most patients relapse due to development of resistance through various mechanisms. This paradigm, by which targeted therapies initially show success in subsets of patients followed by development of resistance, has been seen also for many other novel cancer drugs including Imatinib (Gleevec), and a series of BRAF kinase inhibitors43,44,45,46,47,48. There is therefore a major requirement for approaches that allow us to visualize the signalling networks that control both normal and tumour cell behaviour, to identify signalling hubs that may allow development of synergistic combinations of inhibitors and chemotherapeutic drugs.

Network analysis of genetic control of gene expression has been previously carried out in lower organisms such as yeast49 and has been applied to tissues from heterogeneous populations of mice5,50. We have applied this network analysis approach to matched normal and tumour tissue from patients with lung adenocarcinomas. Analysis of the coordinated changes in gene expression between normal lungs and matched tumours resulted in a ‘progression network’ that displays the main structural and functional components of the lung that show global changes in gene expression during adenocarcinoma development. Lung tumours contain invading immune inflammatory cells, tumour-associated stroma and vascular cell populations. While we believe that motifs representing these cell types are relevant to the overall biology of lung adenocarcinomas, the proportion of epithelial to non-epithelial tissue in each sample is variable, and this cellular heterogeneity will have an impact on the normal and tumour networks. This approach allowed us to identify motifs associated with the major type 2 pneumocyte cell lineage, and the changes in these motifs that accompany transformation to adenocarcinomas. The network identified structural components of the cells in the type 2 pneumocyte lineage (for example, the genes encoding the surfactant proteins) and the transcription factors such as NKX2-1 that are linked to cell type-specific morphogenesis and lineage determination. The NKX2-1 transcription factor is a classical marker for adenocarcinomas and although the surfactant protein gene expression motif is downregulated in the tumours, NKX2-1 remains linked to this network. However, both the progression network and the differential correlation analysis that measures changes in the edges linking genes independently of alteration in actual levels, demonstrated rewiring of NKX2-1 networks in tumours. Novel genes associated with NKX2-1 only in tumours included several genes linked to glutamine and glutathione homoeostasis that are critical for growth and survival of tumour cells. Several of these genes are enzymes that may be suitable for drug development to find combinations of small-molecule inhibitors that coordinately affect this tumour-specific network. Elevated expression of NKX2-1 may for example be a biomarker for tumours suitable for treatment with inhibitors of GLS2 that have already been identified.

NKX2-1 was originally implicated as an oncogene, showing amplification and overexpression in a subset of lung cancers9,10, but more recent data from mouse models suggests that NKX2-1 may act as a tumour suppressor51. High expression of NKX2-1 is linked to tumour metabolism and growth, but the tumours in this category also express high levels of differentiation markers linked to good prognosis52,53,54,55. NKX2-1 may therefore be neither an oncogene nor a tumour suppressor in the classical sense, but act as a mediator of alveolar type 2 lineage determination, loss of which allows development of less well-differentiated tumours expressing new markers of progression. These data may help to rationalize recent controversy regarding the proposed disparate roles for NKX2-1 in lung cancer.9,51 The testing of all possible drug targets or their combinations that can be identified by this network approach is not possible within the scope of the present study. We therefore sought to validate the network predictions, both in normal lungs and in lung tumours, by carrying out immunohistochemical studies on normal lung, primary tumours and cell lines to detect coexpression of network components at the protein level. For normal lung, this analysis identified PEBP4 as a novel marker within the type 2 pneumocyte lineage in the lung. Although this gene is quite widely expressed and is therefore not uniquely expressed in lung-derived cells, it is nevertheless specifically expressed in type 2 pneumocytes both in normal lung and adenocarcinomas, and may therefore be a useful marker for tumours of this lineage. These data, therefore, demonstrate the value of whole-tissue gene expression correlation analysis for identification of markers expressed only or preferentially in specific cell types within the tissue.

To identify potentially novel drug targets in lung tumours, we focused initially on the network motif associated with mitosis, which historically has proven to be a rich source of ‘druggable’ genes for cancer therapy. Inhibitors of several mitotic kinases, including AURKA and AURKB, PLK1-4 and MELK, have been developed and several are presently in clinical trials25,26,27,28,29,30. Initial results using some of these inhibitors have shown that their utility may be limited by toxicity due to inhibition of the cell cycle in completely normal dividing cells. We therefore searched for kinases that are integral components of the cell cycle network in tumours, but are not linked to the same markers in normal tissue such as human lung or mouse skin, which is an example of a proliferative normal tissue. VRK1 was a suitable candidate, as it was not part of the cell cycle network in normal tissue, but was strongly associated with cell cycle and DNA damage response markers in a range of cancer types, including lung (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. S2). BRCA1 mutations are known to induce sensitivity to the effects of PARP inhibition56. We checked the ‘BRCA1’ network in normal lung and matched tumour samples and found that VRK1 and BRCA1 showed a significant correlation only in tumours, and not in normal samples. Moreover, the BRCA1 network showed significant enrichment for genes involved in the cell cycle, DNA repair and DNA damage (cell cycle: P=1.1 × 10−56, DNA repair: P=3.3 × 10−19 and a response to DNA damage: P=4.8 × 10−21)(P-values from BiNGO), which is consistent with known functions of BRCA1 and also confirms the robustness of our network analysis. The strong similarity between the BRCA1 and VRK1 networks suggested that downregulation of VRK1 may be a good strategy for sensitization to PARP inhibition. Downregulation of VRK1 using shRNA resulted in significant growth arrest in lung cancer cells, particularly in combination with a small-molecule inhibitor of PARP. While additional studies will be required to assess VRK1 as a drug target in a range of cancer types, we believe that this study validates the network approach both for identification of coordinated changes in gene expression motifs that are linked to cancer development, as well as for identification of genes within these motifs that may be suitable for drug development. The application of these bioinformatics tools to matched normal and cancer samples from human patients has the potential to elucidate mechanisms of network rewiring in cancer cells that are not dependent on changes in absolute levels of gene expression in tumours—traditionally a prerequisite for identification of a candidate drug target.

Methods

Lung cancer patients

Paired normal/lung tumour (adenocarcinoma) RNA and DNA samples were obtained from patients undergoing surgery at the University of California, San Francisco. All tumour samples in this study were specifically selected to allow a focused analysis of adenocarcinomas, and they contain at least 50% of tumour cells. All samples were obtained from patients with informed consent under the IRB approval of the University of California, San Francisco.

Microarray analysis

RNA was extracted with Trizol followed by DNAse I treatment and purification (RNeasy RNA purification kit, Qiagen). The purified RNA was quantified with Nanodrop and checked by Bioanalyzer for the quality. Gene expression was measured with the Illumina Human Whole Genome 6 2.0 array (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Sample preparations, hybridization and scanning were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 200 ng of total RNA was prepared to make cRNA by using Illumina TotalPrep RNA Amplification Kit (Ambion). First-strand complementary DNA was generated with T7 oligo (dT) primer and ArrayScript and then second cDNA was also made with DNA polymerase.

Biotin-NTP mix with T7 enzyme mix was used to make biotinylated cRNAs. The labelled cRNAs were purified, quantified and checked again with Bioanalyzer. The labelled cRNA target was used for hybridization and scanning according to Illumina Human Whole Genome 6 2.0 array protocol. Probes with present/absent call≥0.05 assessed by Illumina Beadstudio software were marked absent. Probes were re-annotated using data from 57.

Statistical analysis

Raw microarray data were quantile normalized and log2-transformed. Correlation analysis was performed using probes present in ≥90% of samples using Spearman rank correlation. Correlation was defined as significant at the 5% alpha level using the experiment-wise Genome-Wide Error Rate permutation method as described in 58. To calculate tumour progression networks, lung and adenocarcinoma microarrays were normalized together. Change in expression levels between normal and tumour tissue was assessed using a paired t-test in SAM59, retaining genes with false discovery rate≤5% and greater than the twofold change. The progression network was plotted using all differentially expressed gene pairs where correlation in change from normal to tumour was ≥0.7 and where each gene was a member of a clique with size≥3. The decision to use networks of degree 3 was made to enrich for sets of gene, which were correlated with each other without eliminating all but the largest and densest sub-networks. We are using clique membership as a way to increase the likelihood of finding a biologically relevant signal. Gene expression networks were plotted in Cytoscape ( http://www.cytoscape.org). Gene Ontology enrichment was calculated using BiNGO60. Meaningful decreases in correlation was defined as correlation at the GWER alpha-level for the target condition (for example, tumour tissue) and a decrease in correlation magnitude of ≥0.5 in the other condition (for example, normal tissue). To facilitate complete replication of the statistical findings presented in this manuscript from the raw data (Supplementary Data 1–5), a software script is available as Supplementary Software.

Mutation screening

PCR reactions were generally carried out in a volume of 25 μl containing 100 ng genomic DNA, 10 pmol of each primer, 250 μM each dNTP, 0.5 units of Taq polymerase and the reaction buffer provided by the supplier (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Samples were denatured for 5 min at 94 °C in a PCR machine (MJ Research, Inc., MA, USA), and then amplified by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min, with a final elongation of 10 min at 72 °C. Hot-spot areas of K-ras (codons 12 and 13) and TP53 (exons 4–8) were screened by bi-directionally sequencing using the Taq dideoxy terminator cycle sequencing kit and an ABI 3730 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). EGFR mutation was screened by Sequenom OncoCarta panel (Sequenom).

VRK1 shRNA constructs

VRK1 shRNA sequences were designed by BLOCK-iT RNAi Designer (Invitrogen). A shRNA was cloned into pSuper retrovirus cassettes (OligoEngine). The shRNA sequence for VRK1 is 5′-GGAGATATCAAGGCCTCAAAT-3′ (VRK1_sh526). The lung cancer cell lines (A549, NCI-H460 and NCI-H1299) were infected with retroviral stocks produced by the transfection of 293T Phoenix cells using lipofectamin 2000 (Invitrogen). After infection with supernatant medium of VRK1 shRNA-transfected cell, cells were selected with 1–5 μg ml−1 of puromycin. A pSuper vector plasmid without shRNA sequences was used as a control. Cell culture was done with RPMI medium 1640 (Gibco) containing 10% FBS (Gibco), 100 U ml−1 of penicillin, 100 mg ml−1 of streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine.

FACS analysis

Cells were trypsinized in a 5-ml Petri plate with 1 ml of trypsin. After washing with PBS three times, 3 ml of 70% cold EtOH were added to cells and mild vortexing was done. These cells were stored at least overnight in a dark cold room (4 °C) with foil. After incubation at 4 °C, washing with PBS were done three times . Cells were then resuspended in 50 μl PBS with 50 μl RNAse A (Sigma, 5 mg ml−1) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. A volume of 500 μl of propidium iodide (PI, Calbiochem; 50 μg ml−1) was added to the cells and incubated at 4 °C for 30 min in the dark. The prepared cells were analysed with BD FACSCalibur Flow Cytometer and BD CellQuest Pro software. The data was analysed with FLOWJO software (Tree Star, Inc, OR).

IF staining

Cells were seeded and incubated for 24 h in a chamber slide (4-Well Lab-Tek Chamber Slide, BioExpress) and then washed with PBS after removing a medium. A solution with acetone/methanol (1:1) was used for fixing cells for 20 min in −20 °C followed by PBS washing three times. Slide-blocking process was done with solution (10% normal goat serum plus 3% Triton X-100) for 30 min at room temperature. Primary antibodies in a blocking solution were incubated with slides for 2 h at room temperature (dilution 1:500). VRK1 antibodies were used from either Sigma (Rabbit polyclonal, HPA000660) or 1F6 (mouse monoclonal, Cell Signaling, no. 3307S). CDC2 antibody was used from Millipore (06-923). Slides were then washed three times with PBS and incubated with secondary antibody in a blocking solution (1:500 dilution). Alexa 555 goat anti-rabbit IgG (red, Invitrogen) and Alexa488 goat anti-mouse IgG (green, Invitrogen) with DAPI were used for secondary incubation. Slides were washed three times with PBS and checked in a fluorescence microscope.

Immunohistochemistry staining

The same antibodies that were used for IF staining (VRK1 and CDC2) were used for IHC staining. Antibodies for SFTPB (sc-133143, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), SFTPD (sc-25324, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and PEBP4 (HPA025064, Sigma) were used in IHC staining. Sections (5 μm in thickness) were hydrated in xylene and varying concentrations of ethanol and then steamed in citrate from Biogenex for 20 min. The slides were then incubated at room temperature with a blocking solution (10% goat serum in TBS and 1% BSA) for 1 h. A blocking solution was removed and the primary antibody was applied. The slides were incubated at 4 °C overnight. Following the overnight incubation, the slides were rinsed in 1 × TBS containing 0.025% Triton, 1 × TBS containing 0.3% H2O2 and 1 × TBS. The slides were incubated using reagents from the Invitrogen Histostain Plus Broad Spectrum Kit (85-9643) according to the protocol provided by Invitrogen. The slides were rinsed in running water for 5 min and then dipped in Gills no. 2 hematoxylin stain for 1 min. The slides were rinsed in running water for 1 min and dehydrated in xylene and varying concentrations of ethanol. The slides were then mounted using organic mounting media and stored at 4 °C.

PARP inhibitor treatment

ABT-888 (20 μM; Chemie Tek) was treated to cells in a serum-free condition. After 48 h of ABT-888 treatment, cell viability was measured using Promega CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay kit and Synergy HT Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Biotek).

Additional information

Accession codes: microarray data for normal lung and lung tumours has been deposited in the the Gene Expression Omnibus database under series accession code GSE32665

How to cite this article: Kim, I. J. et al. Rewiring of human lung cell lineage and mitotic networks in lung adenocarcinomas. Nat. Commun. 4:1701 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2660 (2013).

Accession codes

References

Edwards B. K. et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975-2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer 116, 544–573 (2010).

Delbaldo C. et al. Second or third additional chemotherapy drug for non-small cell lung cancer in patients with advanced disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 17, CD004569 (2007).

Lynch T. J. et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 2129–2139 (2004).

Pao W. et al. Acquired resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib is associated with a second mutation in the EGFR kinase domain. PLoS Med. 2, e73 (2005).

Quigley D. A. et al. Genetic architecture of mouse skin inflammation and tumour susceptibility. Nature 458, 505–508 (2009).

Quigley D. A. et al. Network analysis of skin tumor progression identifies a rewired genetic architecture affecting inflammation and tumor susceptibility. Genome Biol. 12, R5 (2011).

Lum P. Y. et al. Elucidating the murine brain transcriptional network in a segregating mouse population to identify core functional modules for obesity and diabetes. J. Neurochem. 97, 50–62 (2006).

Mehrabian M. et al. Integrating genotypic and expression data in a segregating mouse population to identify 5-lipoxygenase as a susceptibility gene for obesity and bone traits. Nat. Genet. 37, 1224–1233 (2005).

Weir B. A. et al. Characterizing the cancer genome in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 450, 893–898 (2007).

Kwei K. A. et al. Genomic profiling identifies TITF1 as a lineage-specific oncogene amplified in lung cancer. Oncogene 27, 3635–3640 (2008).

Kolla V. et al. Thyroid transcription factor in differentiating type II cells: regulation, isoforms, and target genes. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 36, 213–225 (2007).

Khoor A., Whitsett J. A., Stahlman M. T., Olson S. J., Cagle P. T. Utility of surfactant protein B precursor and thyroid transcription factor 1 in differentiating adenocarcinoma of the lung from malignant mesothelioma. Hum. Pathol. 30, 695–700 (1999).

Guillot L. et al. NKX2-1 mutations leading to surfactant protein promoter dysregulation cause interstitial lung disease in ‘Brain-Lung-Thyroid Syndrome’. Hum. Mutat 31, E1146–E1162 (2010).

Doyle D. A., Gonzalez I., Thomas B., Scavina M. Autosomal dominant transmission of congenital hypothyroidism, neonatal respiratory distress, and ataxia caused by a mutation of NKX2-1. J. Pediatr. 145, 190–193 (2004).

Garcia R., Grindlay J., Rath O., Fee F., Kolch W. Regulation of human myoblast differentiation by PEBP4. EMBO Rep. 10, 278–284 (2009).

Scanlan M. J. et al. Molecular cloning of fibroblast activation protein alpha, a member of the serine protease family selectively expressed in stromal fibroblasts of epithelial cancers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 5657–5661 (1994).

Anderegg U. et al. MEL4B3, a novel mRNA is induced in skin tumours and regulated by TGF-beta and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Exp. Dermatol. 14, 709–718 (2005).

Gao P. et al. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature 458, 762–765 (2009).

Wang J. B. et al. Targeting mitochondrial glutaminase activity inhibits oncogenic transformation. Cancer Cell 18, 207–219 (2010).

McKay J. D. et al. Lung cancer susceptibility locus at 5p15.33. Nat. Genet. 40, 1404–1406 (2008).

Rafnar T. et al. Sequence variants at the TERT-CLPTM1L locus associate with many cancer types. Nat. Genet. 41, 221–227 (2009).

Hsiung C. A. et al. The 5p15.33 locus is associated with risk of lung adenocarcinoma in never-smoking females in Asia. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001051 (2010).

Possemato R. et al. Suppression of hPOT1 in diploid human cells results in an hTERT-dependent alteration of telomere length dynamics. Mol. Cancer Res. 6, 1582–1593 (2008).

Lee J. et al. TERT promotes cellular and organismal survival independently of telomerase activity. Oncogene 27, 3754–3760 (2008).

Girdler F. et al. Validating Aurora B as an anti-cancer drug target. J. Cell Sci. 119, 3664–3675 (2006).

Fu S., Hu W., Kavanagh J. J., Bast R. C. Jr Targeting Aurora kinases in ovarian cancer. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 10, 77–85 (2006).

Warner S. L., Bearss D. J., Han H., Von Hoff D. D. Targeting Aurora-2 kinase in cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2, 589–595 (2003).

Ko M. A. et al. Plk4 haploinsufficiency causes mitotic infidelity and carcinogenesis. Nat. Genet. 37, 883–888 (2005).

Nakano I. et al. Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase is a key regulator of the proliferation of malignant brain tumours, including brain tumour stem cells. J. Neurosci. Res 86, 48–60 (2008).

Kwiatkowski N. et al. Small-molecule kinase inhibitors provide insight into Mps1 cell cycle function. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 359–368 (2010).

Nezu J., Oku A., Jones M. H., Shimane M. Identification of two novel human putative serine/threonine kinases, VRK1 and VRK2, with structural similarity to vaccinia virus B1R kinase. Genomics 45, 327–331 (1997).

Lopez-Borges S., Lazo P. A. The human vaccinia-related kinase 1 (VRK1) phosphorylates threonine-18 within the mdm-2 binding site of the p53 tumour suppressor protein. Oncogene 19, 3656–3664 (2000).

Valbuena A., Vega F. M., Blanco S., Lazo P. A. p53 downregulates its activating vaccinia-related kinase 1, forming a new autoregulatory loop. Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 4782–4793 (2006).

Valbuena A. et al. Alteration of the VRK1-p53 autoregulatory loop in human lung carcinomas. Lung Cancer 58, 303–309 (2007).

Valbuena A., Lopez-Sanchez I., Lazo P. A. Human VRK1 is an early response gene and its loss causes a block in cell cycle progression. PLoS One 3, e1642 (2008).

Ding L. et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 455, 1069–1075 (2008).

Chin K. et al. Genomic and transcriptional aberrations linked to breast cancer pathophysiologies. Cancer Cell 10, 529–541 (2006).

Fan C. et al. Concordance among gene-expression-based predictors for breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 560–569 (2006).

Ochocka A. M. et al. FKBP25, a novel regulator of the p53 pathway, induces the degradation of MDM2 and activation of p53. FEBS Lett. 583, 621–626 (2009).

Demidova A. R., Aau M. Y., Zhuang L., Yu Q. Dual regulation of Cdc25A by Chk1 and p53-ATF3 in DNA replication checkpoint control. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 4132–4139 (2009).

Turner N. C. et al. A synthetic lethal siRNA screen identifying genes mediating sensitivity to a PARP inhibitor. EMBO J. 27, 1368–1377 (2008).

Chen Z. M., Xu Z., Collins R., Li W. X., Peto R. Early health effects of the emerging tobacco epidemic in China. A 16-year prospective study. JAMA 278, 1500–1504 (1997).

Gorre M. E. et al. Clinical resistance to STI-571 cancer therapy caused by BCR-ABL gene mutation or amplification. Science 293, 876–880 (2001).

Emery C. M. et al. MEK1 mutations confer resistance to MEK and B-RAF inhibition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 20411–20416 (2009).

Montagut C. et al. Elevated CRAF as a potential mechanism of acquired resistance to BRAF inhibition in melanoma. Cancer Res. 68, 4853–4861 (2008).

Comin-Anduix B. et al. The oncogenic BRAF kinase inhibitor PLX4032/RG7204 does not affect the viability or function of human lymphocytes across a wide range of concentrations. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 6040–6048 (2010).

Tsai J. et al. Discovery of a selective inhibitor of oncogenic B-Raf kinase with potent antimelanoma activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 3041–3046 (2008).

Hoeflich K. P. et al. Antitumor efficacy of the novel RAF inhibitor GDC-0879 is predicted by BRAFV600E mutational status and sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway suppression. Cancer Res. 69, 3042–3051 (2009).

Zhu J. et al. Integrating large-scale functional genomic data to dissect the complexity of yeast regulatory networks. Nat. Genet. 40, 854–861 (2008).

Wang K., Narayanan M., Zhong H., Tompa M., Schadt E. E. Meta-analysis of inter-species liver co-expression networks elucidates traits associated with common human diseases. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000616 (2009).

Winslow M. M. et al. Suppression of lung adenocarcinoma progression by Nkx2-1. Nature 473, 101–104 (2011).

Barlési F. et al. Positive thyroid transcription factor 1 staining strongly correlates with survival of patients with adenocarcinoma of the lung. Br. J. Cancer 93, 450–452 (2005).

Martins S. J., Takagaki T. Y., Silva A. G., Gallo C. P., Silva F. B., Capelozzi V. L. Prognostic relevance of TTF-1 and MMP-9 expression in advanced lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer 64, 105–109 (2009).

Perner S. et al. TTF1 expression in non-small cell lung carcinoma: association with TTF1 gene amplification and improved survival. J. Pathol. 217, 65–72 (2009).

Anagnostou V. K., Syrigos K. N., Bepler G., Homer R. J., Rimm D. L. Thyroid transcription factor 1 is an independent prognostic factor for patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 271–278 (2009).

Farmer H. et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 434, 917–921 (2005).

Barbosa-Morais N. L. et al. A re-annotation pipeline for Illumina BeadArrays: improving the interpretation of gene expression data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e17 (2010).

Churchill G. A., Doerge R. W. Empirical threshold values for quantitative trait mapping. Genetics 138, 963–971 (1994).

Tusher V. G., Tibshirani R., Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5116–5121 (2001).

Maere S., Heymans K., Kuiper M. BiNGO: a Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics 21, 3448–3449 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from The Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation (to A.B. and D.J.), the National Cancer Institute U01 CA84244 and RO1 CA111834-01 (to A.B.) and the UALC (Uniting Against Lung Cancer) foundation (to I.-J.K.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.-J.K. designed the study, performed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. D.Q. Analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. M.D.T., K.L., J.-H.M. contributed to the data analysis and a discussion. P.P., B.J., K.-Y.J., D.R., J.K. performed the experiments and contributed to the data analysis and a discussion. D.J. provided human samples and contributed to the clinical data analysis. A.B. designed and supervised the study, performed data analysis and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figures

Supplementary Figures S1-S6 (PDF 1237 kb)

Supplementary Data 1

Raw microarray data (normal tumours). (ZIP 14434 kb)

Supplementary Data 2

Raw microarray data (fold changes). (ZIP 3624 kb)

Supplementary Data 3

Description: Raw microarray data (mouse data). (ZIP 6162 kb)

Supplementary Data 4

Raw microarray data (normal lung). (ZIP 9233 kb)

Supplementary Data 5

Raw microarray data (lung tumours). (ZIP 13491 kb)

Supplementary Data 6

Script for statistical analysis of microarray data. (ZIP 11786 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, IJ., Quigley, D., To, M. et al. Rewiring of human lung cell lineage and mitotic networks in lung adenocarcinomas. Nat Commun 4, 1701 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2660

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2660

This article is cited by

-

PEBP4 deficiency aggravates LPS-induced acute lung injury and alveolar fluid clearance impairment via modulating PI3K/AKT signaling pathway

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2024)

-

Targeting KRAS4A splicing through the RBM39/DCAF15 pathway inhibits cancer stem cells

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Olaparib and ionizing radiation trigger a cooperative DNA-damage repair response that is impaired by depletion of the VRK1 chromatin kinase

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2019)

-

Implication of the VRK1 chromatin kinase in the signaling responses to DNA damage: a therapeutic target?

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2018)

-

Lineage factors and differentiation states in lung cancer progression

Oncogene (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.