Abstract

Doublecortin-like kinase 1 (DCLK1), a microtubule-associated protein kinase, is involved in neurogenesis, and its levels are elevated in various human cancers. Recent studies suggest that DCLK1 may relate to inflammatory responses in the mouse model of colitis. However, cellular pathways engaged by DCLK1, and potential substrates of the kinase remain undefined. To understand how DCLK1 regulates inflammatory responses, we utilized the well-established lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated macrophages and mouse model. Through a range of macrophage-based and cell-free platforms, we discovered that DCLK1 binds directly with the inhibitor of κB kinase β (IKKβ) and induces IKKβ phosphorylation on Ser177/181 to initiate nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway. Deficiency in DCLK1, achieved by silencing or through pharmacological inhibition, prevented LPS-induced NF-κB activation and cytokine production in macrophages. We further show that mice with myeloid-specific DCLK1 knockout or DCLK1 inhibitor treatment are protected against LPS-induced acute lung injury and septic death. Our studies report a novel functional role of macrophage DCLK1 as a direct IKKβ regulator in inflammatory signaling and suggest targeted therapy against DCLK1 for inflammatory diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Doublecortin Like Kinase 1 (DCLK1) is a microtubule-associated protein that was first identified in the developing rodent brain [1,2,3]. It is a multi-domain protein that belongs to the doublecortin (DCX) and the protein kinase super-families [4]. Outside of the nervous system, DCLK1 marks quiescent gastrointestinal and pancreatic stem cells [5]. Increased levels of DCLK1 have also been reported in various human cancers [6]. It is believed that DCLK1 may regulate cell growth by modifying developmental pathways such as NOTCH and WNT. More recently, a few studies have linked DCLK1 and inflammation, suggest that DCLK1 mediates the response to inflammatory factors. For example, recently developed mouse model of spontaneous microbiota-dependent colitis showed that mice lacking intestinal epithelial DCLK1 developed worsened colitis and impaired epithelial proliferative response during inflammation [7]. Similarly, in a dextran sulfate sodium-induced model of colitis, epithelial-specific DCLK1 knockout showed exacerbated injury [8]. High levels of DCLK1 also correlate with increased tumor-associated macrophages [9]. These studies suggest that DCLK1 may regulate inflammation. However, the cellular pathways which may be engaged by DCLK1, as well as its substrates, in inflammation remain undefined. Elucidating these mechanisms is of great significance for inflammatory diseases, including inflammation-associated carcinogenesis.

To discover how DCLK1 may regulate inflammatory responses, we utilized the most canonical lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-challenged macrophage and mouse model [10]. LPS administration in mice induces acute inflammatory responses similar to the response that occurs during the early stages of septic shock. LPS signalling is also relevant to the pathophysiology of chronic inflammatory diseases such as neurodegenerative, metabolic, and cardiovascular diseases [11]. Therefore, LPS-induced cellular and animal models allow exploration of mechanisms of multiple inflammatory diseases and are useful for the discovery of novel biomarkers and drug targets. Binding of LPS to toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activates two main signalling pathways mediated through adaptor proteins myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) or TIR-domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-β (TRIF) [12]. Importantly, downstream of these two arms is the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), a central regulator of inflammatory cytokines and stress responses in many cell types [13]. We reasoned that LPS-challenge in vitro and in vivo models would have a broad implication to inflammatory diseases.

The potential involvement of DCLK1 in the inflammatory response prompted us to explore the potential role of DCLK1 in LPS-induced inflammation. Here, we show that exposure of macrophages to LPS induces the expression of DCLK1. Silencing or inhibition of DCLK1 reduces LPS-induced inflammatory factor expression. Transcriptome analysis revealed that DCLK1 may regulate NF-κB in macrophages. We then used a diverse range of both macrophage-based and cell-free assays to show that DCLK1 directly interacts with inhibitor of κB kinase β (IKKβ) to afford NF-κB activation. In vivo, myeloid-specific DCLK1 knockout and pharmacological inhibition prevented LPS-induced inflammatory responses, lung injury, and septic death in mice. These studies have identified a novel function and mechanism of DCLK1 in inflammatory diseases.

Materials and methods

General reagents and cells

Reagent used in the study, including antibodies, chemicals, recombinant proteins, assay kits, cell lines, and plasmids are provided in Supplementary Table S1. Human embryonic kidney HEK293T and mouse macrophage RAW264.7 lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher) with high glucose and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Human macrophage cell line THP-1 were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FBS and1% penicillin/streptomycin. Before used in the experiments, THP-1 cells were treated with 100 ng/ml PMA for 24 h to differentiate into mature macrophages. Mouse primary peritoneal macrophages (MPMs) were prepared from mice as described previously [14]. Isolated MPMs were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FBS and1% penicillin/streptomycin.

Cell transfections

To express wildtype DCLK1 in HEK-293T cells, transfection with DCLK1 cDNA plasmid pCMV-Flag-DCLK1 was performed using PEI. Briefly, transfection complex was prepared with 3:1 PEI (μg) and plasmid (μg) in 100 μL Opti MEM medium. Logarithmic HEK-293T cells were incubated with transfection complex for 6 h, and then medium was replaced with fresh growth medium. For some studies, the cDNA plasmids for DCLK1 short isoform and DCX domain were designed and expressed in RAW264.7 and HEK293T cells.

To detect interaction between DCLK1 and potential partner proteins, we utilized the Proximity-dependent biotin identification (BioID) platform. The cDNA encoding short DCLK1 was cloned into MCS-BioID2-HA plasmid. HEK 293T cells were transfected with BioID2-DCLK1. Cell lysates, with or without DCLK1 inhibitor (LRRK2-IN-1, D-IN) pretreatment, were then subjected to streptavidin-bead pulldown and routine immunoblotting.

RAW264.7 cells were transfected with NFκB-RE-EGFP reporter (RAW264.7-NFkB-RE-EGFP) as described by us previously [15]. RAW264.7-NFkB-RE-EGFP cells were expanded in media containing 10% FBS and 0.1 μg/mL puromycin. EGFP fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry to determine the level of NF-κB activation.

To express wildtype and mutant IKKβ (S177/181 A) in RAW 264.7 cells, we knocked down the expression of endogenous IKKβ by lentiviral-based RNA-interference (Supplementary Table S2). The fragment targeting mouse IKKβ (5’-GCATCTAGTAGAGCGGATGAT-3’) was cloned into lentiviral plasmids (pSLLV-U6-zsgreen-puro). RAW 264.7 cells were infected with lentivirus particles to target IKKβ or an empty plasmid (negative control; NC). Cells were then selected with 1 μg/mL puromycin. Then, human wildtype (WT) and mutant IKKβ (S177/181 A) cDNA were inserted into lentiviral vectors (pLLV-CMV-G418). Cells were exposed to lentivirus particles and selected with 500 μg/mL G418.

To silence TAK1, DCLK1, MAP7D1 and DCX in RAW 264.7 cells, we transfected cells with targeting siRNA. Sequences for mouse TAK1, DCLK1, MAP7D1, and DCX (Supplementary Table S3) were synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). Negative control transfections included scrambled siRNA sequences. Transfections were carried out for 48 hours using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). To silence TAK1 and DCLK1 in THP1 cells, we transfected cells with targeting siRNA. Sequences for human TAK1 and DCLK1 (Supplementary Table S3). For some studies, DCLK1 was steadily knocked down in RAW264.7 cells through lentiviral particles expressing DCLK1 shRNA (Supplementary Table S2). Briefly, RAW 264.7 cells were incubated with lentivirus particles expressing DCLK1 shRNA and 8 µg/mL polybrene (sigma) for 12 h. Cells were then selected with 2 μg/mL puromycin for 7 days. The monoclonal cell line with the highest knockdown efficiency were selected using limitations of dilution methods. Negative control plasmids contained scrambled sequence.

Real-time qPCR assay

mRNA levels were detected by real-time qPCR. Total RNA from tissues and cells were extracted using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher). One μg total RNA was reverse transcribed using PrimeScript RT with gDNA Eraser. qPCR was performed with iQ SYBR Green Supermix and QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System. Relative gene expression was calculated by 2ΔΔCT method with Actb normalization. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S4.

RNA-sequencing and analysis

Monoclonal cell line RAW 264.7 cell lines which steadily expressed DCLK1 shRNA or negative control shRNA were plated at 200,000 cells/well in six-well plates. Cells were challenged with 500 ng/mL LPS for 6 h. Cells were then homogenized using RNAiso Plus (Takara, Japan) and total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit. A reference transcriptome analysis was performed by Lianchuan Bio (LC-Bio) Technologies (Hangzhou, Zhejiang). Paired-end sequencing was performed using the Illumina Novaseq 6000 (California, United States). RNA-sequencing raw data were analyzed using the methods as described in previous study [16]. GSEA was performed by GSEA4.0 (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/downloads.jsp). Transcription factors motifs and Pathway enriched was analyzed using modEnrichr (https://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/modEnrichr/) and metascape (https://metascape.org/gp/index.html). The RNA sequencing data on RAW264.7 cell lines have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE224030.

Western blot and co-Immunoprecipitation

Total proteins from tissues and cells were prepared using RIPA buffer. Approximately 40-80 μg protein samples were resolved with 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Membranes were blocked in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.4, containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 5% non-fat milk) for 1.5 h at room temperature before applying primary antibodies. Protein bands were visualized by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Thermo Scientific). For some studies, cytosolic and nuclear fractions were separated by using nuclear protein extraction kit (Beyotime Biotech). GAPDH was used as loading control for cytosolic or total extracts and Lamin B for nuclear fractions. Band densities were quantified using Image J software and normalized to loading controls.

For co-immunoprecipitation assays, total proteins were extracted using cell lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail. Extracts were incubated with precipitating antibody overnight at 4 °C. Samples were added to A/G-Sepharose beads at 4 °C for 2 h. After washing with TBS for 5 times, proteins were eluted with SDS loading buffer at 95 °C. Immunoblotting was performed to detect proteins.

Cell-free DCLK1 kinase activity assay

To examine DCLK1 activity, the level of recombinant human IKKβ protein (rhIKKβ) phosphorylation by recombinant human DCLK1 protein (rhDCLK1) was determined. Briefly, 1 or 2 ng/mL rhDCLK1 and 1 μg rhIKKβ were mixed with 1x Kinase reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 1 mM EGTA, 0.01 mM BSA, 0.01 % Tween-20, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM MnCl2, 2 mM DTT) in a 50-μL reaction containing 100 μM ATP. Samples were incubated at 30 °C for 1 h and stopped by adding 4x SDS loading buffer. Phosphorylated IKKβ protein was detected by immunoblotting.

Mass spectrometry

HEK-293T cells were transfected with plasmid expressing mock or FLAG-tagged DCLK1. After 24 h, cells were lysed with co-immunoprecipitation lysis buffer. FLAG-DCLK1 was enriched with anti-FLAG M2 beads at 4 °C overnight. Samples were eluted with 3x FLAG peptide. The samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE gel and Coomassie blue staining. The excised gel segments were subjected to mass spectrometry, with analysis by Hwayen Biomedical Science and Technology Co Ltd (Shanghai, China).

Biotinylating and Streptavidin Pull-Down

To examine DCLK1 and IKKβ complex formation, DCLK1 cDNA was PCR-amplified from pCMV-Flag-DCLK1 and then cloned into MCS-BioID2-HA plasmid. For biotinylation, HEK-293T cell line transfected with DCLK1-BioID2-HA plasmid was pretreated with 10 μM D-IN and then with 50 μm-filter-sterilized biotin and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 24 h. Cells were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer. Cell Lysate was incubated overnight with streptavidin-agarose beads. Protein-bound beads were collected and washed with Strep-biotin wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 1% SDS (w/v), 150 mM NaCl) at room temperature for 5 min. Beads were then washed with RIPA lysis buffer, followed by three washes in TAP lysis buffer (10% glycerol, 0.1% NP-40, 2 mM EDTA (pH 8), 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 100 mM KCl). Finally, beads were boiled with loading buffer, and the samples were loaded on a 10% SDS-PAGE for immunoblotting. Total lysates were used as an input control.

In situ Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA)

In situ PLA was performed using Duolink In Situ PLA Probe. Briefly, cells were fixed and incubated with blocking solution for 30 min at 37 °C. Primary antibodies against DCLK1 (mouse antibody; 1:50 dilution) and IKKβ (rabbit antibody; 1:200 dilution) were applied overnight at 4 °C. The next day, cells were washed in Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 (TBS-T). Cells were then incubated with Duolink PLA probes for 120 min at 37 °C. After the incubation, cells were washed and incubated with hybridization solution containing oligonucleotides to hybridize to the PLA probes for 15 min at 37 °C. Samples were washed and incubated with the ligation solution for 15 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, samples were incubated with amplification solution at 37 °C for 90 min. Finally, samples were incubated with the detection stock solution for 60 min at 37 °C. Images were captured and analyzed.

Bio-layer interferometry binding assays

Bio-layer interferometry assay was performed at 25 °C on Octet RED96 System (ForteBio) with 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 20 mM NaCl and 0.02% Tween-20 as running buffer. rhDCLK1 was biotinylated using EZ-Link Sulfo–NHS–LC-Biotinylation Kit and then loaded for 3 min onto streptavidin biosensors (ForteBio) that had been equilibrated in the running buffer for 10 min. The biosensors were incubated with various concentrations of rhIKKβ for 1 min, followed by 2 min of dissociation. The data were analyzed, and the binding parameters were determined using ForteBio data analysis software.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from ARDS patients

Blood samples from ARDS patients (n = 5) and health volunteers (n = 5) were obtained from the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University. All procedures involving human samples followed the principles in the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Review Ethics Committee in Human of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (Approval no. 2020-021). PBMC and serum were prepared from the whole blood samples. Histological and clinical features of subjects is presented in Supplementary Table S5.

Mouse models of acute lung injury and sepsis

Wildtype C57BL/6 (Strain NO. N000013), B6/JGpt-Dclk1em1Cflox/Gpt (DCLK1-flox, Strain NO. T014962), and B6/JGpt-Lyz2em1Cin(iCre)/Gpt (lysozyme 2 (Lyz2)-driven Cre, Strain NO. T003822) were obtained from GemPharmatech Co. Ltd (Nanjing, China). DCLK1-flox mice were crossed with Lyz Cre mice to generate the myeloid cell-specific DCLK1 knockout mice (DCLK1f/f-LyzCre), as well as the littermate DCLK1f/f mice, in GemPharmatech Co. Ltd (Nanjing, China) (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Validation of genotype of DCLK1f/f and DCLK1f/f-LyzCre mice was performed by PCR using the gene primers (Supplementary Fig. S1B, C). All mice were maintained in pathogen-free facility at Wenzhou Medical University Animal Centre and housed at 23 ± 2 °C with a 12:12 h light/dark cycle and given food and water freely. All care and experimental procedures were approved by Wenzhou Medical University Animal Policy and Welfare Committee (Approval Document No. wydw2019-0224), and all animal experiments conformed the NIH guidelines (Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals).

For LPS administration in 8 weeks old male DCLK1 knockout mice, four groups were examined: DCLK1f/f, DCLK1f/f-LyzCre, DCLK1f/f + LPS, and DCLK1f/f-LyzCre + LPS (n = 6 per group). LPS-treated mice were challenged with 5 mg/kg LPS through intratracheal instillation. Six hours after LPS challenge, mice were sacrificed under 0.2 mL sodium pentobarbital anesthesia (100 mg/mL, ip). Serum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and lung tissue samples were collected.

For pharmacological inhibition of DCLK1, 8 weeks old male wildtype C57BL/6 mice were randomly assigned to one of 4 groups (n = 6): vehicle control (Ctrl), LPS-induced lung injury (LPS; 5 mg/kg), LPS-induced lung injury mice treated with 10 mg/kg of D-IN group (LPS + D-IN-10), and LPS-induced lung injury mice treated with 20 mg/kg of D-IN (LPS + D-IN-20). D-IN was dissolved in 0.5% sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC-Na) and administered at 200 μL/20 g body weight. All D-IN treatments were carried out for three consecutive days prior to LPS challenge. Mice in Ctrl and LPS groups received the same volume of 0.5% CMC-Na. LPS challenge and sacrifice were performed as indicated above.

Serum prepared from mice was used for TNF-α and IL-6 cytokine measurement by ELISA kits. BALF samples were collected from left lungs and used for cytokine and cell measurements. Unirrigated right lungs from the superior lobes were collected, and the weight of wet lungs was recorded immediately after dissection. The collected lungs were then dried at 60 °C for more than 48 h, and dry weights were obtained. The wet/dry lung weight ratio was calculated to assess lung oedema. Portions of lung sections were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin for routine histological analysis following H&E staining. Lung injury scores were determined by using criteria established by the American Thoracic Society for experimental acute lung models [17]. The remaining lung tissues were used for RNA isolation and protein lysate preparation. Neutrophil tissue infiltration was evaluated by myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in lung tissue samples by using the MPO Detection Kit. Lung tissues were homogenized in 1 mL of 50 mM potassium PBS (pH 6.0) containing 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium hydroxide and centrifuged at 15,000 g at 4 °C for 20 min. Ten μL of the supernatant was transferred into PBS (pH 6.0) containing 0.17 mg/ml 3,3′-dimethoxybenzidine and 0.0005% H2O2. MPO activity in the supernatant was determined by measuring absorbance at 460 nm. Total protein levels were measured using Pierce BCA Protein assay kit. Data was presented as U/g tissue.

For the septic shock model, we administered a high dose of LPS or performed bacterial infection. For LPS challenge, LPS at 30 mg/kg was injected in 8 weeks old male DCLK1f/f or DCLK1f/f-LyzCre mice by tail vein. For bacterial infection, E. coli strain DH5α was grown in Luria Broth (LB) and density was determined at 600 nm (OD600) using NanoDrop2000 (Thermo Scientific, San Diego, CA). The corresponding colony-forming units were determined on LB plates. Viable E. coli in 0.5 mL PBS (2 × 109 CFU/mouse) were injected into the peritoneal cavity of 8 weeks old male DCLK1f/f and DCLK1f/f-LyzCre mice. To test the pharmacological effects of DCLK1 inhibitor in these models, 8 weeks old male wildtype C57BL/6 mice were pre-treated with D-IN (10 or 20 mg/kg) or vehicle (10% DMSO in corn oil) through intragastric injections twice a day for one day before LPS or E. coli injection. The survival of mice was monitored during the experiments.

Statistical analysis

All results are presented as Mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using GraphPad Prism. P values were calculated using the Student’s t-test for normally distributed data and the Mann-Whitney rank sum test for non-normally distributed data. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test was used to analyze multiple groups with only one variable tested. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test was used to analyze more than two groups with multiple variables tested. The statistical tests were justified as appropriate according to assessment of normality and variance of the distribution of the data. No randomization or exclusion of data points was used. No ‘blinding’ of investigators was applied.

Results

Kinase domain of DCLK1 mediates LPS-induced inflammatory responses in macrophages

To elucidate the role of DCLK1 in inflammatory responses, we first examined its expression in macrophages following an LPS challenge. For this, we exposed murine macrophage RAW264.7 cells and primary mouse peritoneal macrophages (MPMs) to LPS for different time periods and measured the expression of the two known splice variants of DCLK1 [18, 19] (Fig. 1A). We found that macrophages predominantly induce the expression of the short DCLK1 isoform in response to LPS (Fig. 1B, C, Supplementary Fig. S2). Real-time qPCR assay also showed that both RAW264.7 cells and MPMs transcript the short Dclk1 gene at a high level, but the long Dclk1 gene at a very low level (Supplementary Fig. S3A–C). To test whether macrophage-expressed DCLK1 plays a functional role in LPS-induced inflammatory responses, we utilized two strategies to remove DCLK1. First, we knocked down the expression of DCLK1 in RAW264.7 cells through siRNA (sequence #2, shown in Supplementary Fig. S4). Second, we inhibited DCLK1 through a small-molecule inhibitor LRRK2-IN-1 (D-IN) [20]. Although LRRK2-IN-1 also inhibits LRRK2, our data showed that LPS challenging did not change the level of LRRK2 mRNA in macrophages (Supplementary Fig. S5), indicating that macrophage LRRK2 may be not involved in inflammatory response. Our results show that DCLK1 deficiency normalizes LPS-induced tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin- 6 (IL-6) production in macrophages (Fig. 1D, E). Conversely, we expressed the two DCLK1 isoforms individually, as well as the DCX domain only, in RAW 264.7 and HEK293T cells and show Tnfa induction following long and short DCLK1 expression but not when only DCX domain is expressed (Fig. 1F, G). Furthermore, rescuing DCLK1 expression in DCLK1-deficient MPMs isolated from DCLK1f/f-LyzCre mice by transferring DCLK1 plasmid increased gene transcription of inflammatory cytokines (Supplementary Fig. S6A, B). These data suggest that kinase domain of DCLK1 regulates LPS-induced inflammatory responses in macrophages.

A Schematic showing DCLK1 isoforms and comprising domains. Levels of DCLK1 isoforms in RAW 264.7 (B) and MPMs (C) exposed to 0.5 μg/mL LPS. Proteins levels were detected by immunoblotting. GAPDH was used as loading control. D, E RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with 10 μM DCLK1 inhibitor D-IN for 30 min and then exposed to 0.5 μg/mL LPS for 6 h. Some cells were transfected with negative control siRNA or DCLK1-targeting siRNA and then exposed to LPS. Levels of TNF and IL6 protein (D) and mRNA (E) were measured [n = 4; Mean ± SEM; ***p < 0.001]. F, G Cells were transfected with plasmids encoding DCLK1 long isoform, DCLK1 short isoform, or doublecortin (DCX) domain only. mRNA levels of Tnfa were measured. Figure showing RAW 264.7 (F) and HEK293T (G) cells [n = 6; Mean ± SEM; ns = not significant; *p < 0.05].

DCLK1 regulates LPS-induced inflammatory responses through activation of NF-κB

To identify inflammatory mechanisms downstream of DCLK1, we knocked down the expression of DCLK1 in RAW264.7 cells using shRNA (clone #2, Fig. 2A) and then exposed the cells to LPS. RNA-sequencing (Supplementary Fig. S7) showed 76 LPS-induced genes that were normalized in cells upon DCLK1 silencing (Fig. 2B). Gene ontology analysis of these 76 genes showed that inflammatory pathways are mainly involved (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, transcription factor prediction analysis using four independent methods/systems pointed to potential involvement of NF-κB (Fig. 2D). Indeed, analysis of RNA-Seq data showed that LPS fails to induce NF-κB-related genes in cells following DCLK1 knockdown (Fig. 2E). A select number of these NF-κB-related genes were validated by qPCR in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 2F). We also observed the similar changing profile of these NF-κB-target genes in MPMs isolated from DCLK1f/f and DCLK1f/f-LyzCre mice (Supplementary Fig. S8).

A RAW264.7 cells were transfected with shDCLK1. Control cells were transfected with negative control shRNA (scrambled; shNC). Knockdown efficiency was determined [n = 3; Mean ± SEM]. B RAW264.7 transfected with DCLK1 shRNA were exposed to 0.5 μg/mL LPS for 6 hours. RNA was sequenced to identify differentially expressed genes. Figure showing a Venn diagram of genes upregulated in LPS compared to control (red), and genes downregulated in shDCLK1 + LPS compared to LPS (blue). C Pathway analysis of genes that are increased by LPS but restored in shDCLK1 + LPS. D Transcription factor prediction was performed using PASTAA, chEA2016, ChIP 2015, and TRRUST 2019. E Heatmap showing select NF-κB-target genes which were increased by LPS and restored in shDCLK1 + LPS. F qPCR validation of NF-κB-regulated genes in LPS-challenged RAW 264.7 cells, with or without DCLK1 shRNA transfection. Cells were treated as indicated in B [n = 3; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001].

We confirmed the involvement of NF-κB, downstream of DCLK1, in macrophages by utilizing NF-κB-EGFP reporter. Pretreatment of cells with D-IN prior to LPS challenge showed reduced NF-κB activity compared to cells without DCLK1 inhibitor pretreatment (Fig. 3A). Similarly, knockdown of DCLK1 in macrophages reduced NF-κB activity in response to LPS exposure (Fig. 3B). Conversely, expression of DCLK1 in RAW264.7 cells enhanced NF-κB activity (Fig. 3C). Next, we measured inhibitor of κB (IκB-α) level as a readout of NF-κB activation in cell lysates. Our results show that D-IN pretreatment or DCLK1 knockdown prevents IκB-α degradation in response to LPS exposure and reduces nuclear levels of p65 subunit of NF-κB (Fig. 3D, E, Supplementary Fig. S9). Using MPMs isolated from DCLK1f/f and DCLK1f/f-LyzCre mice, we showed that DCLK1 deletion significantly reversed LPS-induced P65 phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. S10). These results show that DCLK1 mediates NF-κB activation in macrophages.

A RAW264.7 cells were transfected to express NFκB-RE-EGFP reporter. Cells were then treated with 10 μM D-IN for 30 min before exposure to 0.5 μg/mL LPS for 2 hours. NF-κB reporter activity was measured by flow cytometry. B NF-κB reporter RAW264.7 cells were transfected with DCLK1 siRNA or control siNC. Following exposure to 0.5 μg/mL LPS for 2 hours, NFκB activity was measured. C NF-κB reporter RAW264.7 cells were transfected with DCLK1 cDNA plasmid or empty plasmid and exposed to 0.5 μg/mL LPS for 2 hours to measure NF-κB activity. D RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with 10 μM D-IN for 30 minutes or transfected with DCLK1 siRNA. Cells were then exposed to 0.5 μg/mL LPS for 2 hours. Proteins levels of IκBα and p65 were measured. Nuclear fractions were also probed for p65 protein. GAPDH was used as loading control for total cell lysates or cytosolic fractions. Lamin B was used as loading control for nuclear fractions. E RAW264.7 cells were treated as indicated in D. Cells were then fixed and stained for p65 subunit (green). DAPI (blue) was used to counterstain. F RAW264.7 cells transfected with MAP7D1 siRNA were exposed to 0.5 μg/mL LPS for 2 h. Proteins were probed for levels of IκB-α and p65 in cytosol and p65 in nuclear fractions. GAPDH and Lamin B were used as loading control respectively. G, H mRNA levels of Tnfa and Il6 in RAW264.7 cells transfected with MAP7D1 siRNA prior to LPS challenge [n = 3; Mean ± SEM; ns = not significant; ***p < 0.001]. I RAW264.7 cells transfected with DCX siRNA were exposed to 0.5 μg/mL LPS for 2 h. Proteins were probed for levels of IκB-α and p65 in cytosol and p65 in nuclear fractions. GAPDH and Lamin B were used as loading control respectively. J, K mRNA levels of Tnfa and Il6 in RAW264.7 cells transfected with DCX siRNA prior to LPS challenge [n = 3; Mean ± SEM; ns = not significant; ***p < 0.001].

To explore how DCLK1 regulates NF-κB and inflammatory responses in macrophages, we tested whether canonical downstream substrates of DCLK1 are involved. Recent studies indicated that DCLK1 phosphorylates microtubule-associated protein MAP7D1 in cortical neurons [21]. DCLK1 also shares functional redundancy with doublecortin (DCX) in tumorigenesis [22]. Therefore, we assessed whether MAP7D1 and DCX are involved in LPS response. To do this, we knocked down the expression of MAP7D1 and DCX (Supplementary Fig. S11). Interestingly, our data shows that neither MAP7D1 or DCX deficiency reduces LPS-induced NF-κB activation and Tnfa and Il6 induction in macrophages (Fig. 3F–K, Supplementary Fig. S12). These results suggest that DCLK1-mediated inflammatory responses are independent of the canonical MAP7D1 and DCX substrates.

DCLK1 short isoform directly interacts with IKKβ

To decipher how DCLK1 activates NF-κB, we expressed Flag-tagged DCLK1 (short isoform) in HEK293T cells, pulled DCLK1-associating proteins, and performed HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry (Fig. 4A). Among the proteins pulled down, a canonical upstream kinase regulating NF-κB activity, IκB kinase β (IKKβ) was discovered and identified as a potential DCLK1-interacting protein (Fig. 4B). As we know, IKK phosphorylates IκB subunits in NF-κB/IκB complexes, triggering ubiquitin-dependent degradation of IκB and activation of NF-κB. Since IKKβ directly relates to NF-κB activation, we probed this potential mechanism further. Expression of short DCLK1 isoform in HEK293T and RAW264.7 cells and subsequent immunoprecipitation showed robust and selective association between DCLK1 and IKKβ but not IKKα (Fig. 4C, D). We further show that LPS increases DCLK1-IKKβ interaction in RAW264.7 cells, and that inhibiting DCLK1 by D-IN pretreatment, prevents it (Fig. 4E, Supplementary Fig. S13). Similar results were observed in MPMs isolated from wide-type mice (Supplementary Fig. S14). These data show that DCLK1 interacts with IKKβ.

A The schematic diagram showing flow of the Flag pull-down + HPLC/MS/MS method. B Representative mass spectrum showing IKKβ eluted. C, D Cells were transfected with DCLK1 cDNA plasmid or transfection reagent alone (Lipo2000). Lysates were immunoprecipitated with DCLK1 antibody and levels of IKKα and β were detected by immunoblotting. Figure showing HEK 293 T (C) and RAW264.7 cells (D). E RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with 10 μM D-IN for 30 min, and then exposed to 0.5 μg/mL LPS for 1 h. Complex of IKKβ and DCLK1 were detected by co-immunoprecipitation. F HEK 293 T cells were transfected with DCLK1-BioID2-HA plasmid. Cells were then pretreated with 10 μM D-IN before addition of 50 μM biotin. Biotinylated proteins were pulldown with streptavidin-agarose beads. Amount DCLK1 and IKKβ were measured. G The interaction between IKKβ and DCLK1 was detected by PLA assay. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with 10 μM D-IN for 30 min, and then exposed to 0.5 μg/mL LPS for 1 h. Cells were counterstained with DAPI. Arrows showing proximity. H Complex of rhIKKβ and rhDCLK1 was measured in cell-free system, in the presence of D-IN. I Bio-layer interferometry assay showing rhIKKβ binding to biotinylated-rhDCLK1. Sensorgrams of the binding in different concentrations of rhIKKβ (color lines) are shown. Red lines are from model fits.

Next, we utilized Proximity-dependent Biotin Identification (BioID2) platform to examine the direct interaction between DCLK1 and IKKβ. For this assay, we expressed BioID2-DCLK1 in HEK 293 T cells and exposed the cells to D-IN. We then performed streptavidin-bead pulldown and detected DCLK1 and IKKβ interaction (Fig. 4F, Supplementary Fig. S15A). As expected, D-IN treatment reduced the interaction between DCLK1 and IKKβ. A proximity ligation assay (PLA) was also used to visualize DCLK1 and IKKβ interaction in intact cells (Fig. 4G). Next, we detected direct interaction between DCLK1 and IKKβ in a cell-free system by adding recombinant human DCLK1 protein (rhDCLK1, short) and rhIKKβ protein, immunoprecipitating IKKβ and detecting DCLK1 by immunoblotting (Fig. 4H, Supplementary Fig. S15B). In this assay, D-IN also inhibited the interaction. We then used bio-layer interferometry assay to detect rhIKKβ binding to rhDCLK1. This assay showed an apparent affinity with KD value of 1.12e-8 (Fig. 4I). These data, in both intact cells and cell-free systems, show that DCLK1 interacts with IKKβ.

DCLK1 promotes IKKβ phosphorylation at S177/S181 to activate inflammatory responses

Activation of IKKβ depends on its phosphorylation [23]. Specifically, two phospho-accepting serines (S177 and S181) in IKKβ are essential for activation [23] (Fig. 5A). Thus, we explored whether DCLK1 phosphorylates IKKβ at S177/S181 following interaction. We mixed rhDCLK1 and rhIKKβ in the presence of ATP and detected the levels of phospho-IKKβ (S177/181). Our studies show that, indeed, rhDCLK1 increases the phosphorylation of rhIKKβ (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Fig. S16A). D-IN blocked rhDCLK1-mediated IKKβ phosphorylation (Fig. 5C, Supplementary Fig. S16B). Since our earlier studies show that D-IN reduces the interaction between DCLK1 and IKKβ, reduced phosphorylation, perhaps, is not unexpected. Our results further showed that LPS-induced IKKβ phosphorylation in RAW264.7 macrophages, while silencing DCLK1 reduces the level of phosphorylated IKKβ (Fig. 5D, Supplementary Fig. S16C). Pretreatment of cells with D-IN also reduced LPS-mediated IKKβ phosphorylation (Fig. 5E, Supplementary Fig. S16D). Conversely, expression of DCLK1 in RAW264.7 cells increased IKKβ phosphorylation (Fig. 5F, Supplementary Fig. S15E). Interestingly, we did not find DCLK1 expression to be associated with changes to the transforming growth factor-activating kinase 1 (TAK1), a canonical upstream activator of IKKβ (Fig. 5F, Supplementary Fig. S16E). In support of a TAK1-independent mechanism in our experimental system is our finding that either silencing DCLK1 or D-IN pretreatment in RAW264.7 cells fails to reduce LPS-induced TAK1 phosphorylation (Fig. 5D, E, Supplementary Fig. S16C, D). Furthermore, we found that DCLK1 knockout in MPMs failed to affect LPS-induced phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK p38/JNK, a TAK1-dependent signaling pathway) and the upstream TLR4-MyD88 complex formation (Supplementary Fig. S17A, B). These studies suggest that DCLK1 activates IKKβ directly, independent of TLR4/MyD88-TAK1.

A Schematic showing IKKβ protein domains and phosphorylation sites S177/S181 in active loop. B rhDCLK1 was incubated with rhIKKβ in the presence of ATP. rhIKKβ phosphorylation at S177/S181 was detected by immunoblotting (n = 3). C rhDCLK1 was incubated with rhIKKβ, in the presence of ATP and DCLK1 inhibitor D-IN. rhIKKβ phosphorylation at S177/S181 was detected by immunoblotting (n = 3). D RAW264.7 cells were transfected with siDCLK1 and then exposed to 0.5 μg/mL LPS for 1 hour. Representative immunoblots showing the levels of p-IKKβ/IKKβ and p-TAK1/TAK1. GAPDH used as loading control (n = 3). E RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with 10 μM D-IN for 30 min and then exposed to 0.5 μg/mL LPS for 1 hour. Representative immunoblots showing the levels of p-IKKβ/IKKβ and p-TAK1/TAK1 (n = 3). F RAW264.7 cells were transfected with DCLK1 cDNA plasmid. Representative immunoblots showing the levels of p-IKKβ/IKKβ and p-TAK1/TAK1. GAPDH was used as loading control. Lysates were also used to probe for IκBα levels. G RAW264.7 cells were transfected with IKKβ shRNA plasmid. Control cells were transfected with negative control shRNA (scrambled; shNC). Levels of IKKβ were measured following knockdown. H RAW264.7 cells with IKKβ knockdown were transfected with DCLK1 cDNA plasmid. mRNA levels of Il6 and Tnfa were measured [n = 3; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001]. I RAW264.7 cells with IKKβ knockdown (shIKKβ) were infected with lentiviral particles containing human wildtype IKKβ or mutant IKKβ (S177/181 A). Levels of IKKβ were measured following transfections. J mRNA levels of Il6 and Tnfa in RAW264.7 cells manipulated as indicated in I and transfected with or without DCLK1 plasmid [n = 3; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001]. K, L RAW264.7 cells were treated as I. Cells were then exposed to 0.5 μg/mL LPS for 6 h. mRNA levels of Tnfa (M) and Il6 (N) were measured [n = 3; Mean ± SEM; ***p < 0.001].

To determine whether IKKβ plays a role in DCLK1-mediated inflammatory factor expression, we knocked down the expression of endogenous IKKβ in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 5G, Supplementary Fig. S18A) and exposed the cells to LPS. We show that IKKβ is needed for Tnfa and Il6 induction (Supplementary Fig. S18B, C). We then expressed DCLK1 in these cells and show that IKKβ deficiency significantly inhibited DCLK1 overexpression-induced Tnfa and Il6 mRNA expression (Fig. 5H). In contrast, either gene silence or pharmacological inhibition of TAK1 failed to inhibit DCLK1 overexpression-induced Tnfa transcription and IKKβ phosphorylation in both RAW264.7 and 293 T cells, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S19A–H). These data solidly confirm that DCLK1 induces TAK1-independent IKKβ phosphorylation and subsequent inflammatory responses. Finally, we expressed either wildtype IKKβ or mutant IKKβ (S177/181 A) in the IKKβ-deficient RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 5I, Supplementary Fig. S20). Our results indicate that S177/181 sites are critical for both DCLK1- (Fig. 5J) and LPS-induced Tnfa and Il6 (Fig. 5K, L). These results show that DCLK1 mediates activating IKKβ phosphorylation at S177/181 to induce IκB-α degradation and NF-κB activation, and subsequent inflammatory factor expression.

Myeloid-specific DCLK1 knockout mice are protected against LPS-induced lung injury

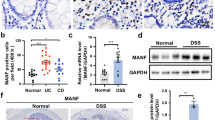

Our in vitro studies prompted us to examine whether DCLK1 mediates inflammatory responses in mouse models. For these studies, mice were administered with a low dose of LPS intratracheally. We harvested peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from mice following LPS challenge. Both cell populations showed increased level of DCLK1 mRNA and protein compared to cells from control mice (Fig. 6A–D, Supplementary Fig. S21A, B). To confirm these results, we recapitulate some key findings in human macrophages. Firstly, our data showed that DCLK1 blockage significantly reversed LPS-induced IKKβ phosphorylation and inflammatory gene expression in human THP-1 cell line (Supplementary Fig. S22A–D). Secondly, we harvested PBMCs from healthy subjects and patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Our results show that DCLK1 expression is elevated in ARDS compared to healthy controls (Fig. 6E, F, Supplementary Fig. S23). Furthermore, DCLK1 levels correlated with increased inflammatory cytokine expression in human PBMCs (Supplementary Fig. S24). These data show that DCLK1 is elevated in inflammatory cells in an experimental model of LPS-induced lung injury, and in PBMCs of patients with ARDS.

A, B PBMC and BALF cells were isolated from mice challenged with intratracheal LPS. Protein levels of DCLK1 short isoform in PBMC (A) and BALF (B) cells. GAPDH was used as loading control. Dclk1 mRNA levels were measured in PBMC (C) and BALF (D) cells [n = 6; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05]. E, F PBMCs were isolated from 5 human subjects with ARDS and heathy volunteers. DCLK1 short isoform protein (E) and mRNA (F) were measured [n = 5; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05]. G DCLK1f/f and DCLK1f/f-LyzCre were challenged with 5 mg/kg intratracheal LPS to induce lung injury. Representative H&E-stained lung tissues are shown. Lung injury scores are shown on right [n = 6; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05]. H Wet/dry lung tissue weights from the experimental groups [n = 6; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05]. Total cell counts (I) and protein levels (J) in BALF samples prepared from mice [n = 6; *p < 0.05]. K Levels of MPO activity in lung tissue lysates [n = 6; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05]. Levels of IL-6 and TNF-α proteins in BALF (L, M) and serum (N, O) of mice [n = 6; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05]. P, Q mRNA levels of Il6 and Tnfa in lung tissues of mice [n = 6; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05]. R Lung tissue lysates of mice were used to examine the levels of p-IKKβ/ IKKβ, IκB-α, and nuclear p65. GAPDH or Lamin B as loading controls (n = 6 per group).

Given the role of macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses in LPS-challenged mice, we assessed the outcome of LPS administration in myeloid-specific DCLK1 deficient DCLK1f/f-LyzCre mice. Histological analysis of lung tissues and lung wet:dry weight ratios showed that DCLK1 knockout mice are protected against LPS-induced lung injury (Fig. 6G, H). In addition, total cells in BALF, as well as total protein levels in BALF confirmed the protective role of DCLK1 deficiency (Fig. 6I, J). Myeloperoxidase activity (MPO), a measure of neutrophilia, also showed increased levels in lung tissues of mice challenged with LPS, but not in DCLK1 knockout mice (Fig. 6K). These results show that myeloid-specific DCLK1 knockout mice fail to exhibit typical LPS-induced lung injury. To build on these results, we assessed inflammatory factors in both BALF and serum samples from these mice. Our results indicate that, although TNF-α and IL6 are induced in DCLK1 knockout mice challenged with LPS, the level of induction is much smaller compared to DCLK1f/f mice (Fig. 6L–O). Levels of lung Tnfa and Il6 transcripts were consistent with the pattern observed in BALF and serum cytokine levels (Fig. 6P, Q). Similarly, other inflammatory factors, including NF-κB response genes were dampened in DCLK1 knockout mice in response to LPS compared DCLK1f/f mice (Supplementary Fig. S25A–F). We also performed immunoblotting assay to assess NF-κB activity. Immunoblotting of lysates obtained from lung tissues of these mice showed that LPS increased IKKβ phosphorylation and NF-κB p65 nuclear translocation and reduced the level of IκB-α in DCLK1f/f mice (Fig. 6R, Supplementary Fig. S26). These measures of NF-κB activity were significantly reduced in DCLK1 knockout DCLK1f/f-LyzCre mice. These results demonstrate that, similar to in vitro studies, DCLK1 deficiency in macrophages prevents LPS-induced NF-κB activation and elaboration of inflammatory cytokines and protects against lung injury.

Pharmacological inhibitor of DCLK1 prevented LPS-induced lung injury

We confirmed our in vivo DCLK knockout modeling study by treating wildtype mice with DCLK1 inhibitor D-IN [24]. Mice received either 10 mg/kg or 20 mg/kg D-IN before LPS challenge. Histological analyses and lung weights indicated that D-IN prevented lung injury in response to intratracheal LPS administration (Fig. 7A, B). Similarly, BALF cell counts and total proteins, as well as MPO activity in lung tissues showed protection in mice treated with D-IN prior to LPS challenge (Fig. 7C–E). Inflammatory cytokine induction in response to LPS was also dampened in mice treated with D-IN, at least with the higher dose (Fig. 7F–I). Cytokine transcript levels in lung tissues were suppressed by D-IN treatment (Fig. 7J, K), consistent with protein levels detected in BALF and serum. Pharmacological inhibitor D-IN also suppressed IKKβ phosphorylation and NF-κB activation following LPS challenge (Fig. 7L, Supplementary Fig. S27A). Increased DCLK1-IKKβ interaction was also observed in LPS-challenged mouse lung tissues, which was reversed by D-IN administration (Fig. 7M, Supplementary Fig. S27B). Taken together, our results show that pharmacological inhibition of DCLK1 significantly reduces LPS-induced inflammatory responses in mice.

A C57BL/6 mice were treated with D-IN (10 or 20 mg/kg, ig) or vehicle alone (10% DMSO and 90% Corn oil) twice a day for one day prior to LPS challenge (5 mg/kg, intratracheal). Representative H&E-stained sections of lung tissues are shown. Lung injury scores are shown on right [n = 6; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05]. B Wet:dry lung tissue weights [n = 6; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05]. Total cell counts (C) and total proteins (D) in BALF [n = 6; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05]. E Levels of MPO activity in lung tissue lysates [n = 6; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05]. Levels of IL-6 and TNF-α proteins in BALF (F, G) and serum (H, I) of mice [n = 6; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05]. J, K mRNA levels of Il6 and Tnfa in lung tissues of mice [n = 6; Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05]. L Lung tissue lysates of mice were subjected to immunoblotting for p-IKKβ/ IKKβ, IκB-α, and nuclear p65. GAPDH or Lamin B as loading controls (n = 6 per group). M Interaction between DCLK1 and IKKβ in lung tissues was examined by immunoprecipitation. Representative immunoblots were shown (n = 6 per group).

DCLK1 deficiency protected mice against LPS-induced septic death

Finally, we examined the effects of DCLK1 deficiency in septic shock from high-dose LPS. Mice were challenged with high-dose intravenous LPS challenge and the survival of mice was monitored. As shown in Fig. 8A, all DCLK1f/f mice treated with LPS alone died within 28 h. However, myeloid-specific DCLK1 deficient mice exhibited significantly increased survival (Fig. 8A). Similar results were obtained when mice were infected with intraperitoneal E. coli (Fig. 8B). We also showed that pharmacological inhibition of DCLK1 by D-IN prior to high-dose LPS challenge or E. coli infection, improved survival rates of mice (Fig. 8C, D).

A DCLK1f/f mice and DCLK1f/f-LyzCre mice were challenged 30 mg/kg LPS through tail vein injection. Survival was monitored every 6 h. B DCLK1f/f and DCLK1f/f-LyzCre mice were infected with 2 × 109 CFU E. coli/mouse. Mouse survival was monitored every 1 h. C C57BL/6 mice were pretreated with D-IN (10 or 20 mg/kg, ig) or vehicle alone (10% DMSO and 90% Corn oil) twice a day for one day prior to LPS challenge (30 mg/kg, iv). Survival was monitored every 6 h. D C57BL/6 mice were pretreated with D-IN (10 or 20 mg/kg, ig) or vehicle alone (10% DMSO and 90% Corn oil) twice a day for one day prior to E. coli infection (2 × 109 CFU). Survival was monitored every 1 h. For all panels, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used for analysis [n = 10 per group; *p < 0.05].

Discussion

Our primary goal in this study was to identify how DCLK1 regulates inflammatory responses. To achieve our goal, we utilized an inflammatory disease model of LPS challenge in macrophages and in mice. Here, we show that LPS-induced inflammatory cytokine production is mediated through DCLK1. mRNA profiling revealed that DCLK1 regulates inflammatory signaling consistent with NF-κB activity. Through a range of in vitro assays, we demonstrate that the kinase domain of DCLK1 physically associates with IKKβ to increase IKKβ-activating phosphorylation. These actions are associated with degradation of IκBα and subsequent activation of NF-κB and inflammatory cytokine expression. Since LPS challenge in mice involves the activation of macrophages, we generated myreloid-specific DCLK1 knockout mice and show that LPS challenge produces significantly less lung damage and inflammatory responses when DCLK1 is deficient. Even with a high dose of LPS, DCLK1 deficiency prolonged the survival of mice. Interestingly these in vivo results can be recapitulated through pharmacological/systemic inhibition of DCLK1 in mice. Collectively, as summarized in the Graphic Abstract, our results show that DCLK1 is a regulator of inflammatory responses and mediates these actions through IKKβ/NF-κB activation.

Known functions of DCLK1 are almost exclusively derived from studies in neurogenesis [25,26,27] and carcinogenesis [28]. Increased levels of DCLK1 in various human cancers including colorectal, renal, breast, pancreatic, and liver have been correlated with cellular activities such as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and cell proliferation and migration [6]. In addition, high DCLK1 expression in colon and gastric cancer correlates with immune cell infiltration, particularly of tumor-associated macrophages [9]. Another study, which linked inflammatory responses to DCLK1, showed that hepatitis B/C- induced liver inflammation was mediated by DCLK1-controlled networks [29]. Specifically, these researchers showed that hepatitis C infection increases DCLK1, which in turn increases S100A9-NFκB inflammatory pathway. These studies promoted us to directly test whether DCLK1 directly plays a role in inflammatory responses. Our studies show that short DCLK1 isoform, which contains the kinase domain, is increased following exposure of macrophages to LPS. This elevated expression of short-DCLK1 mediated LPS-induced inflammatory factor expression. This function of DCLK1 was independent of the known substrates MAP7D1 and DCX. Then, using pulldown assays and HPLC-tandem MS, we report that DCLK1-short isoform specifically interacts with IKKβ and promotes IKKβ phosphorylation. Interaction of DCLK1 with IKKβ was reduced by D-IN, suggesting that the binding site may be common. Downstream of IKKβ, we show that NF-κB activity and cytokine expression is regulated by DCLK1. Mutating IKKβ phosphorylation sites (S177/181 A), generating deficiency in DCLK1, or competitively inhibiting DCLK1 through D-IN, prevents NF-κB activity and inflammatory cytokine expression by macrophages. These studies have provided empirical evidencing linking DCLK1 to inflammatory responses in macrophages and have identified a mechanism involving IKKβ/NF-κB. Interestingly, both DCLK1-IKKβ interaction and DCLK1-mediated IKKβ phosphorylation are found to be independent of TAK1, a classical upstream kinase phosphorylating IKKβ. DCLK1 deficiency also fails to affect the canonical TLR4-MyD88- TAK1 pathway and MAPK signal in LPS-challenged macrophages. These data support DCLK1 as a new and non-canonical IKKβ regulator via directly binding to IKKβ protein.

While DCLK1 overexpression has been reported to contribute to multiple human cancers, the direct contribution of DCLK1-short isoform (kinase domain) to tumorigenesis is not known. Since our studies showed that DCLK1-short isoform promotes IKKβ phosphorylation after DCLK1-IKKβ interaction, question arises as to how? Few studies have examined DCLK1 kinase activity in vitro and in vivo. Not surprisingly, there is no commercial antibodies available for phosphorylated DCLK1. Recently, Patel and colleagues showed that DCLK1 kinase activity negatively regulates the ability of DCLK1 to promote tubulin polymerization [30]. Interestingly, we show that rhDCLK1 directly catalyzes rhIKKβ phosphorylation in the presence of ATP in a cell-free system, indicating that DCLK1-short isoform functions as an independent upstream kinase of IKKβ. A recent study showed that the phosphorylation of Ser-30 is required for DCLK-short isoform to upregulate the expression of pro-opiomelanocortin gene in melanotrope cells [31]. This study indicates that Ser-30 may be an important phosphorylation site for DCLK1 function. We have performed a preliminary study in HEK-293T cells that suggests that expression of DCLK1 with inactivating S30A mutation or DCLK1 with S30D and S30E activating mutations fail to reduce affect pro-inflammatory factor expression (Supplementary Fig. S28A–C). These results suggest that interaction between DCLK1-IKKβ and downstream inflammatory factor expression may require the kinase domain of DCLK1 but may be independent of the Ser-30 site. On the other side, our data also show that DCLK1 interacts with the kinase domain of IKKβ, while the S177/181 A mutation dose not affect the DCLK1-IKKβ interaction (Supplementary Fig. S29A, B). Despite these preliminary studies, it is unclear how DCLK1 binds to IKKβ protein. The molecular mode by which DCLK1 interacts IKKβ and catalyzes IKKβ phosphorylation needs to be defined using co-crystallization study of these two proteins in the future.

Another unanswered question arising from our study is how LPS induces or activates DCLK1. Currently, no physiological activators of DCLK1 have been reported. In cancers, potential mutations in the autoinhibitory domain of DCLK1 may mediate increased kinase activity. In the nervous system, where DCLK1 was first identified, a neuronal calcium sensor family member HPCAL1, has been suggested as an activator of DCLK1 [32]. In cells and systems where both long and short forms of DCLK1 are expressed, association of DCLK1 with microtubules may be involved in DCLK1 activity [33, 34]. Although the mechanisms need to be identified downstream of LPS, it is possible that increased expression of DCLK1 is all that is needed. In support of this rather simple mechanism is our finding that a short exposure of macrophages to LPS increases the level of DCLK1-short isoform. We also show that overexpression of DCLK1, including the short isoform, induces the expression of Tnfa and Il6. Although further studies are needed, it is clear that LPS induces the expression of DCLK1 and increases NF-κB activity and inflammatory factor expression.

In conclusion, our studies establish an important new role of DCLK1 in IKKβ/NF-κB activation. By binding directly to IKKβ and increasing its activating phosphorylation, DCLK1 enhances NF-κB activity in macrophages. Increased proinflammatory cytokines may then initiate organ injury. These studies suggest macrophage DCLK1 has a pathological function in inflammatory diseases and may serve as an important target for the design of therapies. Especially, two recent publications suggest that specific DCLK1 deficiency in intestinal epithelial cells results in worsened colitis through impaired epithelial proliferative response during inflammation. Although our study shows that macrophage DCLK1 increases inflammatory response, the usage of pharmacological DCLK1 inhibitor for the treatment of colitis should be watchful and the outcome needs to be examined in the future.

References

Walker TL, Yasuda T, Adams DJ, Bartlett PF. The doublecortin-expressing population in the developing and adult brain contains multipotential precursors in addition to neuronal-lineage cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3734–42.

Vreugdenhil E, Kolk SM, Boekhoorn K, Fitzsimons CP, Schaaf M, Schouten T, et al. Doublecortin-like, a microtubule-associated protein expressed in radial glia, is crucial for neuronal precursor division and radial process stability. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:635–48.

Sossey-Alaoui K, Srivastava AK. DCAMKL1, a brain-specific transmembrane protein on 13q12.3 that is similar to doublecortin (DCX). Genomics. 1999;56:121–6.

Reiner O, Coquelle FM, Peter B, Levy T, Kaplan A, Sapir T, et al. The evolving doublecortin (DCX) superfamily. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:188.

Cao Z, Weygant N, Chandrakesan P, Houchen CW, Peng J, Qu D. Tuft and Cancer Stem Cell Marker DCLK1: A New Target to Enhance Anti-Tumor Immunity in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers. 2020;12:3801.

Lu Q, Feng H, Chen H, Weygant N, Du J, Yan Z, et al. Role of DCLK1 in oncogenic signaling (Review). Int J Oncol. 2022;61:137.

Yi J, Bergstrom K, Fu J, Shan X, McDaniel JM, McGee S, et al. Dclk1 in tuft cells promotes inflammation-driven epithelial restitution and mitigates chronic colitis. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26:1656–69.

Qu D, Weygant N, May R, Chandrakesan P, Madhoun M, Ali N, et al. Ablation of Doublecortin-Like Kinase 1 in the Colonic Epithelium Exacerbates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134212.

Wu X, Qu D, Weygant N, Peng J, Houchen CW. Cancer Stem Cell Marker DCLK1 Correlates with Tumorigenic Immune Infiltrates in the Colon and Gastric Adenocarcinoma Microenvironments. Cancers. 2020;12:274.

Remick DG, Newcomb DE, Bolgos GL, Call DR. Comparison of the mortality and inflammatory response of two models of sepsis: lipopolysaccharide vs. cecal ligation and puncture. Shock. 2000;13:110–6.

Page MJ, Kell DB, Pretorius E. The role of lipopolysaccharide-induced cell signalling in chronic inflammation. Chronic Stress. 2022;6:24705470221076390.

Gay NJ, Symmons MF, Gangloff M, Bryant CE. Assembly and localization of Toll-like receptor signalling complexes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:546–58.

Oeckinghaus A, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Crosstalk in NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:695–708.

Pan Y, Wang Y, Cai L, Cai Y, Hu J, Yu C, et al. Inhibition of high glucose-induced inflammatory response and macrophage infiltration by a novel curcumin derivative prevents renal injury in diabetic rats. Br J Pharm. 2012;166:1169–82.

Chen L, Chen H, Chen P, Zhang W, Wu C, Sun C, et al. Development of 2-amino-4-phenylthiazole analogues to disrupt myeloid differentiation factor 88 and prevent inflammatory responses in acute lung injury. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;161:22–38.

Halder L, Jo E, Hasan M, Ferreira-Gomes M, Krüger T, Westermann M, et al. Immune modulation by complement receptor 3-dependent human monocyte TGF-β1-transporting vesicles. Nat Commun. 2020;11:2331.

Matute-Bello G, Downey G, Moore BB, Groshong SD, Matthay MA, Slutsky AS, et al. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: features and measurements of experimental acute lung injury in animals. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:725–38.

Engels BM, Schouten TG, van Dullemen J, Gosens I, Vreugdenhil E. Functional differences between two DCLK splice variants. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;120:103–14.

Burgess HA, Reiner O. Alternative splice variants of doublecortin-like kinase are differentially expressed and have different kinase activities. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17696–705.

Weygant N, Qu D, Berry WL, May R, Chandrakesan P, Owen DB, et al. Small molecule kinase inhibitor LRRK2-IN-1 demonstrates potent activity against colorectal and pancreatic cancer through inhibition of doublecortin-like kinase 1. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:103.

Koizumi H, Fujioka H, Togashi K, Thompson J, Yates JR 3rd, Gleeson JG, et al. DCLK1 phosphorylates the microtubule-associated protein MAP7D1 to promote axon elongation in cortical neurons. Dev Neurobiol. 2017;77:493–510.

Jean DC, Baas PW, Black MM. A novel role for doublecortin and doublecortin-like kinase in regulating growth cone microtubules. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:5511–27.

Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Chen Y, Karin M. Positive and negative regulation of IkappaB kinase activity through IKKbeta subunit phosphorylation. Science. 1999;284:309–13.

Sureban SM, May R, Weygant N, Qu D, Chandrakesan P, Bannerman-Menson E, et al. XMD8-92 inhibits pancreatic tumor xenograft growth via a DCLK1-dependent mechanism. Cancer Lett. 2014;351:151–61.

Shu T, Tseng HC, Sapir T, Stern P, Zhou Y, Sanada K, et al. Doublecortin-like kinase controls neurogenesis by regulating mitotic spindles and M phase progression. Neuron. 2006;49:25–39.

Koizumi H, Tanaka T, Gleeson JG. Doublecortin-like kinase functions with doublecortin to mediate fiber tract decussation and neuronal migration. Neuron. 2006;49:55–66.

Deuel TA, Liu JS, Corbo JC, Yoo SY, Rorke-Adams LB, Walsh CA. Genetic interactions between doublecortin and doublecortin-like kinase in neuronal migration and axon outgrowth. Neuron. 2006;49:41–53.

Chhetri D, Vengadassalapathy S, Venkadassalapathy S, Balachandran V, Umapathy VR, Veeraraghavan VP, et al. Pleiotropic effects of DCLK1 in cancer and cancer stem cells. Front Mol Biosci. 2022;9:965730.

Ali N, Chandrakesan P, Nguyen CB, Husain S, Gillaspy AF, Huycke M, et al. Inflammatory and oncogenic roles of a tumor stem cell marker doublecortin-like kinase (DCLK1) in virus-induced chronic liver diseases. Oncotarget. 2015;6:20327–44.

Patel O, Dai W, Mentzel M, Griffin M, Serindoux J, Gay Y, et al. Biochemical and Structural Insights into Doublecortin-like Kinase Domain 1. Structure. 2016;24:1550–61.

Kuribara M, Jenks BG, Dijkmans TF, de Gouw D, Ouwens DT, Roubos EW, et al. ERK-regulated double cortin-like kinase (DCLK)-short phosphorylation and nuclear translocation stimulate POMC gene expression in endocrine melanotrope cells. Endocrinology. 2011;152:2321–9.

Burgoyne RD, Helassa N, McCue HV, Haynes LP. Calcium sensors in neuronal function and dysfunction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2019;11:a035154.

Lin PT, Gleeson JG, Corbo JC, Flanagan L, Walsh CA. DCAMKL1 encodes a protein kinase with homology to doublecortin that regulates microtubule polymerization. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9152–61.

Kim MH, Cierpicki T, Derewenda U, Krowarsch D, Feng Y, Devedjiev Y, et al. The DCX-domain tandems of doublecortin and doublecortin-like kinase. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:324–33.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81930108 to GL, 82000793 to WL, and 82170373 to YW), Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LY22H070004 to WL), and Zhejiang Provincial Key Scientific Project (2021C03041 to GL).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GL, YW, and WL contributed to the literature search and study design. GL and WL participated in the drafting of the article. WL, YJin, YJiang, LYang, HX, DW, YZ, and LYin carried out the experiments. GL, ZAK, and YW revised the manuscript. LYin, YW, and WL contributed to data collection and analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, W., Jin, Y., Jiang, Y. et al. Doublecortin-like kinase 1 activates NF-κB to induce inflammatory responses by binding directly to IKKβ. Cell Death Differ 30, 1184–1197 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-023-01147-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-023-01147-8