Abstract

Recent years have seen a surge of interest in ecosystem multifunctionality, a concept that has developed in the largely separate fields of biodiversity–ecosystem function and land management research. Here we discuss the merit of the multifunctionality concept, the advances it has delivered, the challenges it faces and solutions to these challenges. This involves the redefinition of multifunctionality as a property that exists at two levels: ecosystem function multifunctionality and ecosystem service multifunctionality. The framework presented provides a road map for the development of multifunctionality measures that are robust, quantifiable and relevant to both fundamental ecological science and ecosystem management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The idea of holistic ‘whole ecosystem’ properties and measures has a long history in ecology1. However, research into the ability of ecosystems to simultaneously provide multiple ecosystem functions and services (multifunctionality) has become increasingly common in recent years, as comprehensive datasets and model outputs from multidisciplinary, collaborative projects have become available2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. To date, multifunctionality has been defined only broadly, for example, as ‘the simultaneous provision of multiple functions’9 and ‘the potential of landscapes to supply multiple benefits to society’11. However, underlying these seemingly simple definitions are complex and unresolved issues regarding the conceptualization and measurement of multifunctionality9,10,11, and the overall utility of the multifunctionality concept in practice12,13,14,15. Research on multifunctionality has been carried out within two largely separate research fields: one that seeks to understand how biotic attributes of ecological communities (mainly biodiversity) are related to overall ecosystem functioning (biodiversity–ecosystem functioning research); and the other that concerns how landscapes can be managed to deliver multiple, alternative land-use objectives (land management research). Accordingly, these two fields have defined and measured multifunctionality in very different ways.

Here, we first discuss the potential benefits of the multifunctionality concept, and the advances it has enabled, before discussing the risks and drawbacks of current approaches to studying multifunctionality. We show how more explicit definitions of multifunctionality are required to overcome these hurdles and to answer both fundamental and applied research questions. In light of these challenges we propose a new general framework that defines multifunctionality at two levels. The first, ‘ecosystem function multifunctionality’, is most relevant to fundamental research into the drivers of ecosystem functioning, which we define as the array of biological, geochemical and physical processes that occur within an ecosystem. The second, ‘ecosystem service multifunctionality’, we define as the co-supply of multiple ecosystem services relative to their human demand, and is most relevant for applied research in which stakeholders have definable management objectives. These ideas are illustrated with worked examples from European forests. We conclude by showing how this framework can be extended to measure multifunctionality on the larger spatial and temporal scales where it is most relevant.

Benefits of the multifunctionality concept

Traditional studies of ecosystem functioning within the field of ecosystem ecology typically involve detailed investigations into how individual functions relate to their drivers. Moreover, by quantifying functions in a standardized way (for example, soil carbon fluxes, biomass production) these measures can be compared among ecosystems and studies15. However, ecosystem functioning is inherently multidimensional and so multifunctionality measures can potentially complement this approach by summarizing the ability of an ecosystem to deliver multiple functions or services simultaneously. Just as aggregated community-level properties such as species richness, evenness and functional diversity16,17 have provided great insight into broad ecological patterns at a higher level of organization, multifunctionality research could generate an integrative understanding of ecosystem functioning and ecosystem service provision.

The concept of ecosystem multifunctionality has recently gained traction with the publication of several studies that assessed the relationship between biodiversity and multifunctionality within experimental systems2,3,18,19. While these studies concluded that the relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem functioning becomes stronger when multiple functions are considered20,21, it has been shown that positive diversity–multifunctionality relationships can be driven by statistical averaging effects alone22. An increasing number of studies have also shown positive relationships, but of varying strength, between biodiversity and the multifunctionality of non-experimental ‘real-world’ (that is, natural, semi-natural and human-dominated) ecosystems, where management and abiotic drivers additionally affect functioning10,23,24,25,26,27,28.

The multifunctionality concept used in biodiversity–ecosystem functioning research overlaps with ideas developed in research fields related to landscape-level management of ecosystem services, where there is a long history of studying the drivers of ‘multifunctional landscapes’, although the term multifunctionality itself is not always used. The motivation for such work is that a growing and resource-hungry human population is placing increasing pressure on dwindling land resources29, resulting in a need to design and manage landscapes that can reliably provide multiple ecosystem services simultaneously. For example, the concept of landscape multifunctionality permeates discussions over the design of landscapes in which food and bioenergy production, carbon storage, flood regulation and biodiversity conservation are all goals7,8,30. Landscape multifunctionality is also central to the ‘land sparing’ versus ‘land sharing’ debate, which focuses on the relative merits of managing for biodiversity and food production within the same or separated land areas31,32.

Measurement of multifunctionality

To date there has been no single accepted definition of multifunctionality, nor any agreed means of measuring it. In biodiversity–ecosystem functioning studies the main methods for quantifying ecosystem-level multifunctionality are the ‘averaging’ (or sum) approach and the ‘threshold’ approach. The averaging approach takes the average, or sum, of the standardized values of each function28,33. In contrast, the threshold approach9,18 counts the number of functions that have passed a threshold, or a range of thresholds, usually expressed as a percentage of the highest observed level of functioning in a study9,18,23,2734. The conceptual and mathematical merits of these approaches have been discussed and reviewed from the viewpoint of biodiversity–ecosystem function research9,22,35, but their relevance to other fields of fundamental ecological research, and to the management of ‘real-world’ ecosystems, has not.

Averaging- and threshold-based multifunctionality measures are now being related to a wide range of other ecosystem drivers, including climate25,28,34, soil conditions36, habitat diversity37, land cover changes38, nitrogen enrichment12,39, invasive species40 and management actions, such as agricultural intensification10, pasture and green roof planting schemes41,42, and crop planting systems39,43,44. These advances have blurred the line between the multifunctionality concepts used in the biodiversity–functioning and land management research fields. In the latter, multifunctionality is defined more broadly than it is in biodiversity research, and it can even encompass social factors such as employment and benefits provided by human infrastructure (for example, transport systems) in addition to ecosystem components45,46. Furthermore, multifunctionality is typically considered on much larger (landscape) scales than in most biodiversity research, and there is sometimes consideration of both the demand for ecosystem services (the level of service provision desired by people47) and their supply (the capacity of an ecosystem to provide a given ecosystem service47). Maps of multiple ecosystem service supplies are often overlain to assess trade-offs and synergies between them48,49, to identify ecosystem service bundles, that is, a set of services with a similar pattern of supply50,51,52, or to find hotspots of multiple ecosystem services that can be prioritized for conservation48,49. These approaches could be extended to create more explicit measures of ecosystem service multifunctionality that can inform a diverse range of ecosystem management decisions, with potential applications including the setting of restoration targets, invasive species management, forest planting and the design of agri-environment schemes. Multifunctionality measures can also indicate the overall benefit provided by an ecosystem to a range of stakeholder groups, thereby helping to minimize trade-offs and conflicts between them10.

Multifunctionality risks

While the concept of multifunctionality can be useful in both fundamental and applied ecology, its measurement is extremely challenging. Any multifunctionality measure will always comprise a subset of all possible functions or services and so will capture only a fraction of ‘true’ multifunctionality. Unfortunately, so far, few researchers have carefully defined what their subset of functions represents and what it omits. It is also clear that the definition of multifunctionality determines how it is measured, and vice versa. Hence, the different perspectives in biodiversity and land management research and the intermingling of these fields mean that a better conceptualization of multifunctionality is required.

As with any aggregated measure, multifunctionality metrics simplify reality, and can obscure important information about variation in individual functions and their drivers12. Many drivers have contrasting effects on the component functions of a multifunctionality measure, meaning that trade-offs between ecosystem functions and services are common, and it is impossible to maximize all functions simultaneously. For example, promoting soil nutrient turnover often results in the release of carbon dioxide, thus boosting one ecosystem service (crop production) while diminishing another (carbon storage)39. Where such trade-offs exist, there is therefore uncertainty in how well measures of multifunctionality reflect mechanistic relationships12,13,14. A new method for measuring multifunctionality, the multivariate diversity–interactions framework35, overcomes some of these limitations by testing the relative importance of drivers across functions and identifying trade-offs between them. This provides considerable insight into the drivers of each function, but the method does not provide a measure of overall multifunctionality, and its complexity and reliance on detailed data may limit its widespread adoption.

Current standard practice in both averaging- and threshold-based approaches is to include all available measures of ecosystem functions and services, to include a mix of state, rate and indicator variables, and to weight all variables equally12,23,25,26,27,36. It is also common for multiple closely related variables to be included in multifunctionality measures. This causes the up-weighting of certain aspects of ecosystem functioning or particular ecosystem services, biasing the multifunctionality measurement, especially if other important ecosystem functions are not measured. Furthermore, such measures assume that all functions are equally important, which may be a false assumption in many cases, as ecosystem managers typically prioritize certain functions or services in particular contexts. To address this issue, a recent study in European grasslands10 weighted functions according to their presumed importance to different management objectives, such as agricultural production or tourism. This demonstrated that the identity and importance of the drivers of multifunctionality, such as land-use intensification and biodiversity, depended greatly on how multifunctionality was defined. To extend this approach, realistic measures of how different stakeholders value each ecosystem service are required.

It has been argued that the threshold approach is the most informative of the current approaches, especially when metrics are calculated for multiple thresholds9. A notable benefit of the threshold approach is that it avoids assumptions regarding the substitutability of functions and services that the averaging approach does not. However, it does not reflect the significance of particular functions or services, as it treats all functions passing an arbitrary threshold as equivalent. Furthermore, threshold-based metrics are highly sensitive to the means of standardization and the number of functions included22. Specifically, the method of standardization affects the mean and distribution of function values, and achieving 100% multifunctionality becomes increasingly unlikely as the number of functions increases22. Furthermore, different studies, using both averaging and threshold approaches, include different numbers and sets of ecosystem functions, which are standardized according to different local maxima10,23,53. This renders comparisons of multifunctionality measures across studies extremely challenging22. The mixing of functions and services also means that many multifunctionality measures are difficult to interpret from both fundamental and applied perspectives.

A final issue is that multifunctionality is rarely measured on the large spatial scales relevant to most management decisions: almost all multifunctionality measures have been calculated on the ‘plot’ scale (<1 ha). In some cases the delivery of multiple ecosystem services is required on these small scales, for example in smallholder subsistence farms, but landscape-level multifunctionality is often the priority for land managers, for instance when managing watersheds54. Initial investigations into the drivers of landscape-level multifunctionality show that it is driven by factors other than those determining local-scale multifunctionality, such as the spatial turnover in species composition53, and the variety and identity of different land uses and habitat types37,55. In land management research there is a plethora of frameworks for assessing patterns in landscape multifunctionality, which frequently highlight the need to understand trade-offs and synergies between ecosystem services as key to maximizing landscape multifunctionality46,56. Although earlier attempts to measure landscape multifunctionality (sensu lato) have been made57, the frameworks of land management research tend to lack explicit procedures for quantitatively measuring overall landscape multifunctionality11. For example, the delivery of multiple individual services is described6,49, or hotspot approaches are used to identify locations where several services are at high supply, but not whether this supply exceeds or falls short of demand. It may be possible to represent multifunctionality as the total economic value of the ecosystem, but such approaches are demanding and typically fail to account for certain ecosystem values (for example, those of cultural ecosystem services), or to represent the non-equivalence of ecosystem service values between stakeholder groups58,59.

In summary, a lack of conceptual clarity in the definition of multifunctionality has led to multifunctionality measures that are subjective and difficult to interpret. Accordingly, the use of such measures could lead to erroneous conclusions about the drivers of ecosystem functioning and to poor management decisions.

Redefining multifunctionality

We propose that studies should clearly differentiate between (1) measures of multifunctionality including only ecosystem functions, which therefore constitute a metric of the overall performance of an ecosystem, which we term ecosystem function multifunctionality (EF-multifunctionality); and (2) measures that include ecosystem services and where multifunctionality is defined and valued from a human perspective, which we term ecosystem service multifunctionality (ES-multifunctionality). A key distinction between these measures is that EF-multifunctionality attempts to objectively represent overall ecosystem functioning without any value judgement regarding the desired level or types of function, whereas ES-multifunctionality represents the supply of ecosystem services relative to human demand. These two multifunctionality types need to be calculated according to different procedures, which we outline below (see also Boxes 1 and 2). Throughout the process of measuring multifunctionality, we recommend the use of standardized definitions of ecosystem functions and services60,61, which would increase comparability between studies.

EF-multifunctionality

A standardized approach to defining and measuring multifunctionality is desirable in fundamental research on the drivers of ecosystem functioning, and for long-term monitoring of ecosystem conditions. In the following section, we describe calculation methods for calculating EF-multifunctionality that are designed to be as objective as possible and at the same time repeatable. The first barrier to achieving standardized and comparable measures is that there is little consensus on the definition of ecosystem functioning, and on what can be considered high levels of function62. A truly standardized and comparable measure of EF-multifunctionality is not likely to be possible until ecologists resolve long-running debates regarding the nature of ecosystem function, including whether states, rates and processes should all be considered functions. As a full discussion of this topic is outside the scope of this Perspective, we work here from the basis that ecosystem functioning should ideally be defined solely on processes rates, that is, those involving fluxes of energy and matter between trophic levels and the environment, with high functioning being defined by fast rates. High stocks of energy and matter (for example, soil carbon stocks, algal biomass) can also be considered indicators of process rates over the long term, as they represent the net balance of inputs and outputs. However, care should be taken in interpreting them as they may either represent high rates of accumulation or low rates of biological activity, and it is important to clearly justify why a high or low stock indicates high or low functioning. Alternatives to this approach, in which ecosystem functioning or multifunctionality is defined relative to specific or desired levels, immediately take the measure outside objective fundamental sciences and into the more subjective realm of ES-multifunctionality (see below). This approach suggested in this section avoids such value judgements.

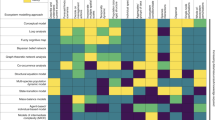

The next step towards the development of standardized EF-multifunctionality measures is to assess which variables represent independent aspects of ecosystem functioning. To date, many multifunctionality metrics have attempted to represent overall ecosystem functioning by including as many different types of function as possible3,23,26,28,53,63. However, ecosystem functions are numerous and interrelated via networks of interactions and shared drivers (for example, those related to nutrient cycling and productivity). Accordingly, EF-multifunctionality measures should avoid bias caused by overweighting certain categories of function. As researchers will differ greatly in their definitions of these subsets, we suggest that they are defined as objectively as possible, by applying a cluster analysis to all ecosystem function data, after first standardizing the variables to make them comparable (panel a of the figure in Box 1).

Once the clusters are identified they can be used to define weightings in threshold-based multifunctionality measures. In contrast to ES-multifunctionality measures (see below), there is no particular level of each function that is desired by people, so we consider threshold-based approaches6 to be appropriate as long as each cluster is weighted equally in the EF-multifunctionality measure, irrespective of the number of functions within each cluster. This will prevent the overrepresentation of many similar functions. Prior to this analysis, a standardized maximum for each function should be defined (for example, using existing data) and used to place the function data on a standardized scale, thus making studies comparable. As the indicator functions, and the means of measuring them, are likely to differ according to ecosystem type, standardization should be performed at the level of major ecosystem types (for example, grassland, forest, dryland, urban, cropland, wetland, lake, river, coastal, or open ocean), or relative to the likely maximum potential function given local conditions, if this can be determined. As certain clusters or functions may be of particular interest, we also suggest that users should report results for individual functions and clusters separately.

As the clustering method is sensitive to the identity of the functions used in the analysis, this process will produce system-specific measures for the time being. However, as studies accumulate, certain common groupings of functions are likely to become recognizable. This, in turn, may allow us to identify standard indicators of multifunctionality in the future, for which rapid and standardized ecosystem assessments64 can be developed. The identification of standard indicator functions and EF-multifunctionality measures would be greatly accelerated by the collation and analysis of ecosystem function data at a global level. To achieve a fully comprehensive and comparable measure of multifunctionality, we need to evaluate how many, and which, functions are necessary to measure to obtain a good representation of overall ecosystem functioning (that is, the dimensionality of ecosystem functioning). In such an initiative, the dimensionality of ecosystem functioning can be assessed by identifying associations between a fully comprehensive set of ecosystem functions (for example, with principal component analysis), measured across a very wide range of conditions. Fundamental axes of ecosystem variation could then be identified and causes of variation along these will become better understood, in a process similar to what has been achieved for broad plant functional strategies, where fundamental axes of variation across plant species and communities are broadly accepted65.

Delivering a set of accurate, comparable and easily measured indicators of ecosystem function that have been validated across a wide range of conditions is clearly a non-trivial task, yet it has the potential to provide significant insight into the drivers of ecosystem functioning and to help in identifying fundamental trade-offs and synergies between ecosystem functions. Such standardized measures are not without precedent as they are being used to monitor spatio-temporal changes in ecosystem functioning on continental scales worldwide66, and they are roughly analogous to the use of indicator taxa in conservation monitoring, or to the measurement of a few plant traits to represent major axes of functional trait variation65. Furthermore, standard EF-multifunctionality indicator measures could be linked to related schemes to monitor climate and biodiversity change via ‘essential variables’67.

In the short term, we advise a cautious approach to the use of EF-multifunctionality measures that should acknowledge the mathematical and conceptual sensitivity of these measures to the functions included, and that is transparent in reporting any biases in selecting variables. We also recommend reporting the degree of trade-off between functions (for example, as a correlation matrix) and the maximum EF-multifunctionality present within a study. Ideally, this should be related to a theoretical or standardized maximum, so that cases where high EF-multifunctionality is impossible, for example due to strong trade-offs between functions, are identified. Regardless of the wider property that an EF-multifunctionality measure represents, it is imperative that researchers justify their choice of ecosystem function measures and understand the implications of these choices in driving their conclusions. We also recommend that EF-multifunctionality scores are compared with null expectations, given their sensitivity to the form of standardization and number of contributing functions, and given that tools exist for their computation22.

ES-multifunctionality

As ecosystem services are defined in relation to human needs, the definition and measurement of ES-multifunctionality requires a different approach. The first step is to define which ecosystem services (including material, regulating and non-material relational values68) are desired, and the level and scale on which they are to be delivered. This requires consulting stakeholders69,70. As priorities differ depending on stakeholder identities, and local socio-economic and ecological factors, a single ES-multifunctionality measure would not be globally meaningful. Instead, bespoke ES-multifunctionality measures are needed to reflect the supply of ecosystem services relative to their demand with respect to various groups and organizations (panel a of the figure in Box 2). This should be done in a two-stage process using social science methodologies. First, the identity of important stakeholder groups and the services they value are identified qualitatively (for example, via interview and discourse), before the weightings of these services are derived quantitatively (for example, by deriving stated preferences from stakeholder questionnaires in which the importance of different ecosystem services are ranked on an ordinal scale70).

Once the main ecosystem services and their relative importance have been defined, the next step is to describe the functional relationship between the supply of each service and the benefit delivered in terms of a relevant measure of wellbeing (for example, economic benefit, health, security or equity), which we term the supply–benefit relationship. The threshold approach9,18 is a particular case of this relationship that assumes an abrupt shift from zero to full benefit at a particular level. Previous work on ecosystem services has found that such relationships can take a wide range of forms, for example, threshold, asymptotic or linear. This emphasizes the need to construct ES-multifunctionality measures in which the supply–benefit relationship is derived for each service71 (panel a of the figure in Box 2). We suggest that many locally relevant, regulating services show a threshold relationship in which there are definable safe levels (for example, a safe maximum threshold for nitrate in drinking water), while ecosystem services that operate on very large scales (for example, climate regulation via carbon storage) can show a linear relationship with benefits on local scales. Ecosystem services with direct economic benefits, on the other hand, might show a ‘threshold-plus’ relationship, characterized by a break-even point, beyond which increasing levels of a service deliver increasing benefits (for example, there is a minimum crop yield that will be profitable, beyond which further yields generate further profits; see Supplementary Table 1 for further examples). The supply–benefit relationship can be defined using a range of techniques, many of which were developed in economics69,71, and — where relevant — they may be defined separately for different stakeholder groups. Where it is difficult to determine the supply–benefit relationship, or it is uncertain, we suggest exploring the sensitivity of ES-multifunctionality metrics to a range of possible relationships (see Box 3; Supplementary Information).

As a next step, ecosystem services need to be quantified. The services described by stakeholders will generally denote broad categories, so effort is required to convert these to quantifiable properties. In certain cases, they can be measured directly, for example, carbon stocks72. However, many other services do not have generally applicable metrics, and so locally relevant indicators, ideally with direct links to the final service, need to be identified. Furthermore, multiple indicators may be required in cases where services have several components (panel a of the figure in Box 2; Box 3). Once identified and measured, indicator variables should then be transformed to service values using mathematical transfer functions that are appropriate for the function–service relationship7,8 (see Box 3; Supplementary Information). Then, the standardized values can be multiplied by the stakeholder-derived weightings (see Box 2) and finally be summed to generate ES-multifunctionality measures. With this method, issues with substitutability9 and with applying the same supply–benefit relationship (for example, a 50% threshold) to all services are largely avoided. Also, the preliminary assessment of stakeholder needs means that all important services for each area should be included, thus providing a comprehensive measure of ES-multifunctionality. This ensures that measures are comparable within a study, even where the number of services differs.

Once ES-multifunctionality measures have been calculated, their relationship to biotic (for example, the presence of a keystone species) and abiotic (for example, climate or land-use) drivers can be investigated for a range of stakeholder groups (panel b of the figure in Box 2), and the resulting knowledge can inform landscape management. For example, simulating changes in the most important drivers may allow for the prediction of future changes in ES-multifunctionality to different stakeholder groups, or the costs and benefits of different management actions. Such information is compatible with existing environmental decision-making frameworks, such as the driving forces–pressures–states–impacts–responses framework used by the European Environment Agency73 or the conceptual framework of the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services74. These recommended ES-multifunctionality measures advance on existing approaches50,51 by delivering an integrated measure of the supply of ecosystem services relative to their demand from a wide range of stakeholders, rather than simply indicating the supply of multiple ecosystem services6, or coarsely estimating their total value59. In addition to ES-multifunctionality, the response of individual underlying services should also be reported for transparency and to allow individual practitioners to assess the data. This can be summarized concisely in the form of flower diagrams and radar charts6,50,51,63,75.

Landscape-scale multifunctionality

In the previous sections we assumed that multifunctionality is measured on small spatial scales (often <1 ha). However, as mentioned earlier, high levels of ES-multifunctionality are often desired on much larger scales (often >1 ha), where factors such as beta diversity, connectivity and landscape configuration may become important drivers of multifunctionality37,53,76,77. There have been previous attempts to measure landscape multifunctionality within biodiversity–ecosystem function research, where it has been quantified as the number of functions exceeding a threshold in at least one part of a landscape, and also as the average of standardized function measures across a landscape53,78. These previous studies measured multifunctionality by aggregating properties of plot-level measures, however, and thus were not able to consider spatial interactions between organisms and landscape features, which can strongly influence some ecosystem functions, particularly in heterogeneous and complex landscapes45,75,76. Where such interactions occur, simple extrapolation of existing knowledge of the drivers of local-scale multifunctionality to larger scales is not recommended as it is highly likely that whole landscape functioning is not equal to the sum of the functioning of small landscape units. In this section we suggest possible approaches to address this challenge and to quantify ES-multifunctionality on the landscape scale.

The first steps towards the measurement of landscape ES-multifunctionality are to ensure that the landscape is divided into analytically manageable units, for example, even-sized grid cells or patches undergoing uniform management, such as fields, which can then be used in upscaling calculations. Next, appropriate scaling functions should be applied to each ecosystem service of interest to calculate its overall level within the landscape (Fig. 1). For certain services, simple upscaling methods — in which the supply of a service is estimated from the properties of each landscape unit and then summed or averaged across the landscape — will be appropriate, for example, carbon storage, which can be estimated from simple local measures or remote-sensing proxies72. However, many services and their underlying functions involve spatial exchanges of matter and organisms, for example, nutrient leaching, pollination services or pest control75,76,79. These will be strongly influenced by surrounding features, making direct upscaling from local-level measures unreliable. Therefore, the quantification of such services will require spatially explicit algorithms in which the levels of an ecosystem service in each landscape unit are modified by features of the local environment. Finally, some important ecosystem services are not observable on local scales at all and so require landscape-level assessment, or estimation from the aggregated properties of smaller landscape units. Examples are landscape beauty, habitat suitability for organisms with large range sizes (for example, many charismatic vertebrates) or landslip risk (Fig. 1). Ecosystem services can be attributed to these categories of upscaling method by combining expert knowledge with quantitative assessment of which local-level services are influenced by surrounding features75. Such assessments could also provide the algorithms required to upscale each function or service (for example, from spatially explicit statistical models).

Two hypothetical landscapes possess the same proportion of two habitat types, pasture (yellow) and forest (green), but differ in their spatial configuration. Different ecosystem services require different upscaling functions. Carbon (C) storage (S2) can be estimated simply from the area of crop and forest, while nutrient leaching into water bodies, which reduces water quality (S1), is buffered by forest, thus requiring spatially explicit consideration, as does food production, which is affected here by the proximity of livestock to water (S3). The charismatic vertebrate (S4) responds to landscape structure and requires a connected habitat, requiring measurements of habitat suitability to be made on the landscape scale. The preferred landscape structure differs between two stakeholder groups: the ecotourism industry and farmers, although trade-offs between these two groups are notably weaker in the extensive landscape. Note that nutrient leaching, the indicator of water quality, is inverted to represent a lack of leaching, a positive service, in the supply–benefit relationship.

The next step in measuring landscape ES-multifunctionality is to define the supply–benefit relationship spatially, that is, to define the location and level required for each service. Certain services may be required at very high levels, but only in certain locations (for example, recreation, avalanche control), while for others only their overall landscape level is important (for example, carbon storage). This spatial supply–benefit relationship should be defined by a range of stakeholders because they may differ in their spatial pattern of demand80. For example, a landscape formed of small subsistence farms requires multiple benefits in many landscape positions, whereas land belonging to a single owner (for example, a large private company or conservation charity) may require larger-scale ES-multifunctionality, with large areas dedicated to a small number of services. Once the spatial pattern of supply relative to demand is determined for each service, landscape-level ES-multifunctionality can be quantified as described previously (Fig. 1).

Future avenues

Given the complexity and diversity of ecosystem functions and services, it is conceivable that the framework presented here may require adaptation for certain circumstances. It is also clear that several gaps in knowledge and data, for example, the identity of the best indicators within clusters of related ecosystem functions, or the spatial patterns of ecosystem service benefits, need to be addressed before EF- and ES-multifunctionality can be quantified with confidence. Temporal aspects also bring further complexity to the measurement of multifunctionality, which may explain the paucity of knowledge on this subject. Nevertheless, such aspects are essential for understanding the stability, resistance and resilience of overall ecosystem performance and its long-term benefits for human well-being. Time-series data give the potential to extend multifunctionality measures, for example, by quantifying the number of years in which an ecosystem had high levels of multiple functions, thus merging measures of stability77,81 and multifunctionality9,18 to give measures of multifunctional stability. Future linkages between ecological and socio-economic systems are also encouraged, and are possible through the extension of the framework presented here, for example, by quantifying ES-multifunctionality using monetary or life-satisfaction82 units.

Conclusions

Multifunctionality is a simple but nebulous concept with many potential applications. It is increasingly studied in fundamental biodiversity and ecosystem science, while also becoming a common objective for ecosystem management and landscape-scale policy. There is therefore a pressing need to define it clearly and to provide useful multifunctionality metrics. With careful consideration of the issues raised here, multifunctionality metrics will become well founded, thus giving them the potential to provide important insights in ecosystem science and to support environmental decision-making. The recommendations made in this Perspective often require greater resources and effort than current approaches, and it is still unlikely that all can be implemented within a single study. However, data-intensive methods are becoming increasingly possible thanks to large collaborative projects2,3,4,5,6,7,8 and data-sharing, opening the possibility to identify general indicators of ecosystem functions and services, which may then be applied widely. By focusing research efforts on well-designed sampling protocols that include the most relevant and easy-to-measure functions and services, we can further accelerate this process. Even before such protocols are devised, increased awareness of the issues covered here will help to prevent inappropriate conclusions from being drawn from multifunctionality studies. Producing new and more reliable measures of EF- and ES-multifunctionality is not a trivial challenge, but a highly worthwhile one, given their great potential to provide insight into whole ecosystem functioning and to guide ecosystem management in an era in which dwindling natural resources are placed under increasing pressure.

Change history

13 August 2018

In the version of this Perspective originally published, in the figure in Box 3 the middle panel of the top row was incorrectly labelled ‘50% threshold-plus’; it should have read ‘50% threshold’. This has now been corrected.

References

Odum, E. P. Fundamentals of Ecology (Saunders, Philadelphia, 1953).

Hector, A. & Bagchi, R. Biodiversity and ecosystem multifunctionality. Nature 448, 188–190 (2007).

Zavaleta, E. S., Pasari, J. R., Hulvey, K. B. & Tilman, D. Sustaining multiple ecosystem functions in grassland communities requires higher biodiversity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1443–1446 (2010).

Fischer, M. et al. Implementing large-scale and long-term functional biodiversity research: the Biodiversity Exploratories. Basic Appl. Ecol. 11, 473–485 (2010).

Baeten, L. et al. A novel comparative research platform designed to determine the functional significance of tree species diversity in European forests. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 15, 281–291 (2013).

Clough, Y. et al. Land-use choices follow profitability at the expense of ecological functions in Indonesian smallholder landscapes. Nat. Commun. 7, 13137 (2016).

Nelson, E. et al. Modeling multiple ecosystem services, biodiversity conservation, commodity production, and tradeoffs at landscape scales. Front. Ecol. Environ. 7, 4–11 (2009).

Bateman, I. J. et al. Bringing ecosystem services into economic decision making: land use in the United Kingdom. Science 341, 45–50 (2013).

Byrnes, J. E. et al. Investigating the relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem multifunctionality: challenges and solutions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 5, 111–124 (2014). Reviews the current methods for measuring multifunctionality in biodiversity–ecosystem function research.

Allan, E. et al. Land use intensification alters ecosystem multifunctionality via loss of biodiversity and changes to functional composition. Ecol. Lett. 18, 834–843 (2015). Shows that the relationship between multifunctionality and its drivers depends on stakeholder priorities and the weighting of different functions.

Mastrangelo, M. E. et al. Concepts and methods for landscape multifunctionality and a unifying framework based on ecosystem services. Landsc. Ecol. 29, 345–358 (2014).

Bradford, M. A. et al. Discontinuity in the response of ecosystem processes and multifunctionality to altered soil community composition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 14478–14483 (2014). The first paper to question the capacity of multifunctionality measures to represent overall ecosystem function..

Bradford, M.A. et al. Reply to Byrnes et al.: Aggregation can obscure understanding of ecosystem multifunctionality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, E5491 (2014).

Byrnes, J. et al. Multifunctionality does not imply that all functions are positively correlated. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, E5490 (2014).

Sala, O. E., Jackson, R. B., Mooney, H. A. & Howarth, R. W. (eds) Methods in Ecosystem Science (Springer, New York, 2000).

Magurran, A. Ecological Diversity and its Measurement (Springer, New York, 1988).

Petchey, O. L. & Gaston, K. J. Functional diversity: back to basics and looking forward. Ecol. Lett. 9, 741–758 (2006).

Gamfeldt, L., Hillebrand, H. & Jonsson, P. R. Multiple functions increase the importance of biodiversity for overall ecosystem functioning. Ecology 89, 1223–1231 (2008).

Duffy, J. E. et al. Grazer diversity effects on ecosystem functioning in seagrass beds. Ecol. Lett. 6, 637–645 (2003).

Isbell, F. et al. High plant diversity is needed to maintain ecosystem services. Nature 477, 199–202 (2011).

Lefcheck, J. S. et al. Biodiversity enhances ecosystem multifunctionality across trophic levels and habitats. Nat. Commun. 6, 6936 (2015).

Gamfeldt, L. & Roger, F. Revisiting the biodiversity–ecosystem multifunctionality relationship. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0168 (2017).

van der Plas, F. et al. ‘Jack-of-all-trades’ effects drive biodiversity–ecosystem multifunctionality relationships. Nat. Commun. 7, 11109 (2016).

Berdugo, M., Kéfi, S., Soliveres, S. & Maestre, F. T. Plant spatial patterns identify alternative ecosystem multifunctionality states in global drylands. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0003 (2017).

Delgado-Baquerizo, M. et al. Microbial diversity drives multifunctionality in terrestrial ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 7, 10541 (2016).

Soliveres, S. et al. Locally rare species influence grassland ecosystem multifunctionality. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20150269 (2016).

Soliveres, S. et al. Biodiversity at multiple trophic levels is needed for ecosystem multifunctionality. Nature 536, 456–459 (2016).

Maestre, F. T. et al. Plant species richness and ecosystem multifunctionality in global drylands. Science 335, 214–218 (2012).

Bajželj, B. et al. Importance of food-demand management for climate mitigation. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 924–929 (2014).

Manning, P., Taylor, G. & Hanley, M. E. Bioenergy, food production and biodiversity - an unlikely alliance? GCB Bioenergy 7, 570–576 (2015).

Phalan, B., Onial, M., Balmford, A. & Green, R. E. Reconciling food production and biodiversity conservation: land sharing and land sparing compared. Science 333, 1289–1291 (2011).

Batary, P. et al. The former Iron Curtain still drives biodiversity–profit trade-offs in German agriculture. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1279–1284 (2017).

Mouillot, D., Villéger, S., Scherer-Lorenzen, M. & Mason, N.W. Functional structure of biological communities predicts ecosystem multifunctionality. PLoS ONE 6, e17476 (2011).

Perkins, D. M. et al. Higher biodiversity is required to sustain multiple ecosystem processes across temperature regimes. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 396–406 (2015).

Dooley, A. F. et al. Testing the effects of diversity on ecosystem multifunctionality using a multivariate model. Ecol. Lett. 18, 1242–1251 (2015).

Mori, A. S. et al. Low multifunctional redundancy of soil fungal diversity at multiple scales. Ecol. Lett. 19, 249–259 (2016).

Alsterberg, C. et al. Habitat diversity and ecosystem multifunctionality—the importance of direct and indirect effects. Sci. Adv. 3, e1601475 (2017).

Soliveres, S. et al. Plant diversity and ecosystem multifunctionality peak at intermediate levels of woody cover in global drylands. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 12, 1408–1416 (2014).

Wood, S. et al. Agricultural intensification and the functional capacity of soil microbes on smallholder African farms. J. Appl. Ecol. 52, 744–752 (2015).

Constán-Nava, S., Soliveres, S., Torices, R., Serra, L. & Bonet, A. Direct and indirect effects of invasion by the alien tree Ailanthus altissima on riparian plant communities and ecosystem multifunctionality. Biol. Invasions 17, 1095–1108 (2015).

Lundholm, J. T. Green roof plant species diversity improves ecosystem multifunctionality. J. Appl. Ecol. 52, 726–734 (2015).

Storkey, J. et al. Engineering a plant community to deliver multiple ecosystem services. Ecol. Appl. 25, 1034–1043 (2015).

Finney, D. M. & Kaye, J. P. Functional diversity in cover crop polycultures increases multifunctionality of an agricultural system. J. Appl. Ecol. 54, 509–517 (2016).

Sircely, J. & Naeem, S. Biodiversity and ecosystem multi-functionality: observed relationships in smallholder fallows in western Kenya. PLoS ONE 7, e50152 (2012).

Brandt, J. Multifunctional landscapes – perspectives for the future. J. Env. Sci. 15, 187–192 (2003).

de Groot, R. Function analysis and valuation as a tool to assess land use conflicts in planning for sustainable, multi-functional landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 75, 175–186 (2006).

Maron, M. et al. Towards a threat assessment framework for ecosystem services. Trends Ecol. Evol. 32, 240–248 (2017).

Chan, K. A. M., Shaw, M. R., Cameron, D. R., Underwood, E. C. & Daily, G. Conservation planning for ecosystem services. PLoS Biol. 4, e379 (2006).

Lavorel, S. et al. Using plant functional traits to understand the landscape distribution of multiple ecosystem services. J. Ecol. 99, 135–147 (2011).

Raudsepp-Hearne, C., Peterson, G. D., & Bennett, E. M. Ecosystem service bundles for analyzing tradeoffs in diverse landscapes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 5242–5247 (2010). An important example of the ecosystem services approach to describing the co-supply of multiple ecosystem services on large scales.

Mouchet, M. A. et al. Bundles of ecosystem (dis)services and multifunctionality across European landscapes. Ecol. Indic. 73, 23–28 (2017).

Stürck, J. & Verburg, P. H. Multifunctionality at what scale? A landscape multifunctionality assessment for the European Union under conditions of land use change. Landsc. Ecol. 32, 481–500 (2017).

van der Plas, F. et al. Biotic homogenization can decrease landscape-scale forest multifunctionality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 3557–3562 (2016).

Whittingham, M. J. The future of agri-environment schemes: biodiversity gains and ecosystem service delivery? J. Appl. Ecol. 48, 509–513 (2011).

Polasky, S. et al. Where to put things? Spatial land management to sustain biodiversity and economic returns. Biol. Conserv. 141, 1505–1524 (2008).

Bennett, E. M., Peterson, G. D. & Gordon, L. J. Understanding relationships among multiple ecosystem services. Ecol. Lett. 12, 1394–1404 (2009).

Tongway, D. & Hindley, N. Landscape function analysis: a system for monitoring rangeland function. Afr. J. Range Forage Sci. 21, 109–113 (2004).

Keith, H. et al. Ecosystem accounts define explicit and spatial trade-offs for managing natural resources. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1683–1692 (2017).

Plottu, E. & Plottu, B. The concept of total economic value of environment: a reconsideration within a hierarchical rationality. Ecol. Econ. 61, 52–61 (2007).

Haines-Young, R. & Potschin, M. CICES V4.3-Report Prepared following Consultation 440 on CICES Version 4, August–December 2012 EEA Framework Contract No. 441 EEA/IEA/09/003 (Univ. Nottingham, Nottingham, 2013).

Maes, J. et al. An indicator framework for assessing ecosystem services in support of the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020. Ecosyst. Serv. 17, 14–23 (2016).

Jax, K. Ecosystem Functioning (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2010).

Gamfeldt, L. et al. Higher levels of multiple ecosystem services are found in forests with more tree species. Nat. Commun. 4, 1340 (2013).

Meyer, S. T., Koch, C. & Weisser, W. W. Towards a standardised rapid ecosystem function assessment (REFA). Trends Ecol. Evol. 30, 390–397 (2015).

Diaz, S. et al. The global spectrum of plant form and function. Nature 529, 167–171 (2016).

Herrick, J. E. et al. National ecosystem assessments supported by scientific and local knowledge. Front. Ecol. Environ. 8, 403–408 (2010).

Pereira, H. M. et al. Essential biodiversity variables. Science 339, 277–278 (2013).

Chan, K. M. A. et al. Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1462–1465 (2016).

Derak, M. & Cortina, J. Multi-criteria participative evaluation of Pinus halepensis plantations in a semiarid area of southeast Spain. Ecol. Indic. 43, 56–68 (2014).

Darvill, R. & Lindo, Z. The inclusion of stakeholders and cultural ecosystem services in land management trade-off decisions using an ecosystem services approach. Landsc. Ecol. 31, 533–545 (2016).

Mace, G. M., Hails, R. S., Cryle, P., Harlow, J. & Clarke, S. J. Towards a risk register for natural capital. J. Appl. Ecol. 52, 641–653 (2015).

Manning, P. et al. Simple measures of climate, soil properties and plant traits predict national‐scale grassland soil carbon stocks. J. Appl. Ecol. 52, 1188–1196 (2015).

Maxim, L., Spandenberg, J. H. & O’Connor, M. An analysis of risks for biodiversity under the DPSIR framework. Ecol. Econ. 69, 12–23 (2009).

Díaz, S. et al. The IPBES Conceptual Framework - connecting nature and people. Curr. Opin. Env. Sust. 14, 1–16 (2015).

Mitchell, M. G. E., Bennett, E. M. & Gonzales, A. Forest fragments modulate the provision of multiple ecosystem services. J. Appl. Ecol. 51, 909–918 (2014).

Tscharntke, T. et al. Landscape moderation of biodiversity patterns and processes‐eight hypotheses. Biol. Rev. 87, 661–685 (2012).

Oliver, T. H. et al. Biodiversity and resilience of ecosystem functions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 30, 673–684 (2015).

Pasari, J. R., Levi, T., Zavaleta, E. S. & Tilman, D. Several scales of biodiversity affect ecosystem multifunctionality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 10219–10222 (2013).

Hooda, P. S., Edwards, A. C., Anderson, H. A. & Miller, A. A review of water quality concerns in livestock farming areas. Sci. Total Environ. 250, 143–167 (2000).

Wolff, S., Schulp, C. J. E. & Verburg, P. H. Mapping ecosystem services demand: a review of current research and future perspectives. Ecol. Indic. 55, 159–171 (2015).

Allan, E. et al. More diverse plant communities have higher functioning over time due to turnover in complementary dominant species. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17034–17039 (2011).

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J. & Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75 (1985).

Fürstenau, C. et al. Multiple-use forest management in consideration of climate change and the interests of stakeholder groups. Eur. J. For. Res. 126, 225–239 (2007).

Acknowledgements

C. Penone, M. Felipe Lucia and M. Perring provided useful comments on earlier versions of the paper. P.M. acknowledges support from the German Research Foundation (DFG; MA 7144/1-1). F.T.M. acknowledges support from the European Research Council (ERC grant agreement 647038 (BIODESERT)). We thank the FunDivEUROPE consortium (EU Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013), grant agreement 265171) for support and for the data used in the examples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.M. conceived the study and wrote the initial draft, which was developed and revised by all other authors. P.M. and F.v.d.P. designed and performed analyses.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Supplementary Note

R based tutorial demonstrating how ecosystem function and ecosystem service multifunctionality can be quantified, as shown in examples 1 and 2, and the decision-making process behind this

Supplementary Data

Data used in Examples 1 and 2. Originally used in ref. 51. See ref. 51 for methods

Supplementary Code 1

R scripts for the quantification of EF-multifunctionality and ES-multifunctionality, used to compute example 1

Supplementary Code 2

R scripts for the quantification of EF-multifunctionality and ES-multifunctionality, used to compute example 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Manning, P., van der Plas, F., Soliveres, S. et al. Redefining ecosystem multifunctionality. Nat Ecol Evol 2, 427–436 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0461-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0461-7

This article is cited by

-

Towards the intentional multifunctionality of urban green infrastructure: a paradox of choice?

npj Urban Sustainability (2024)

-

Microbial diversity loss and wheat genotype-triggered rhizosphere bacterial and protistan diversity constrain soil multifunctionality: Evidence from greenhouse experiment

Plant and Soil (2024)

-

Network complexity and community composition of key bacterial functional groups promote ecosystem multifunctionality in three temperate steppes of Inner Mongolia

Plant and Soil (2024)

-

The social–ecological ladder of restoration ambition

Ambio (2024)

-

Relative importance of altitude shifts with plant and microbial diversity to soil multifunctionality in grasslands of north-western China

Plant and Soil (2024)