Abstract

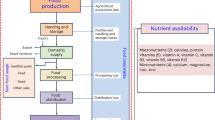

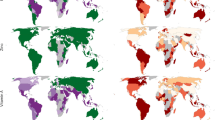

Adequate supplies of healthy foods available in each country are a necessary but not sufficient condition for adequate intake by each individual. Here we provide complete nutrient balance sheets that account for all plant-based and animal-sourced food flows from farm production through trade to non-food uses and waste in 173 countries from 1961 to 2018. We track 36 bioactive compounds in all farm commodities recorded by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, accounting for nutrient-specific losses in processing and cooking as well as bioavailability. We compare supply with requirements given each country’s age–sex distribution and find that the adequacy of food supplies has increased but often remains below total needs, with even faster rise in energy levels and lower density of some nutrients per calorie. We use this nutrient accounting to show how gaps could be filled, either from food production and trade or from selected biofortification, fortification and supplementation scenarios for nutrients of concern such as vitamin A, iron and zinc.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data used in this study are publicly available from open sources as indicated in the references in Methods. The NBS and NNRD will be made available at: https://sites.tufts.edu/willmasters. Inquiries related to the NBS should be made to K.L., keith.lividini@tufts.edu.

Code availability

All data analysis was carried out in Stata SE 15–17. All figures were produced in Stata. The code used for data analysis and figure production is available from the corresponding author upon request and will be made available at https://sites.tufts.edu/willmasters.

References

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. Transforming Food Systems For Affordable Healthy Diets (FAO, 2020).

FAO. Food balance sheets: a handbook. FAO http://www.fao.org/3/X9892E/X9892E00.htm (2001).

Thar, C.-M. et al. A review of the uses and reliability of food balance sheets in health research. Nutr. Rev. 78, 989–1000 (2020).

Arsenault, J. E., Hijmans, R. J. & Brown, K. H. Improving nutrition security through agriculture: an analytical framework based on national food balance sheets to estimate nutritional adequacy of food supplies. Food Secur. 7, 693–707 (2015).

Broadley, M. R. et al. Dietary requirements for magnesium, but not calcium, are likely to be met in Malawi based on national food supply data. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 82, 192–199 (2012).

Chilimba, A. D. et al. Maize grain and soil surveys reveal suboptimal dietary selenium intake is widespread in Malawi. Sci. Rep. 1, 72 (2011).

Gibson, R. S. & Cavalli-Sforza, T. Using reference nutrient density goals with food balance sheet data to identify likely micronutrient deficits for fortification planning in countries in the Western Pacific region. Food Nutr. Bull. 33, S214–S220 (2012).

Joy, E. J. M. et al. Risk of dietary magnesium deficiency is low in most African countries based on food supply data. Plant Soil 368, 129–137 (2013).

Joy, E. J. M. et al. Dietary mineral supplies in Africa. Physiol. Plant. 151, 208–229 (2014).

Kumssa, D. B. et al. Dietary calcium and zinc deficiency risks are decreasing but remain prevalent. Sci. Rep. 5, 10974 (2015).

Kumssa, D. B. et al. Global magnesium supply in the food chain. Crop Pasture Sci. 66, 1278–1289 (2016).

Mark, H. E. et al. Estimating dietary micronutrient supply and the prevalence of inadequate intakes from national food balance sheets in the South Asia region. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 25, 368–376 (2016).

Schaafsma, T. et al. Africa’s oesophageal cancer corridor: geographic variations in incidence correlate with certain micronutrient deficiencies. PLoS ONE 10, e0140107 (2015).

Sheehy, T. & Sharma, S. The nutrition transition in the Republic of Ireland: trends in energy and nutrient supply from 1961 to 2007 using Food and Agriculture Organization food balance sheets. Br. J. Nutr. 106, 1078–1089 (2011).

Tennant, D. R. et al. Phytonutrient intakes in relation to European fruit and vegetable consumption patterns observed in different food surveys. Br. J. Nutr. 112, 1214–1225 (2014).

Wessells, K. R. & Brown, K. H. Estimating the global prevalence of zinc deficiency: results based on zinc availability in national food supplies and the prevalence of stunting. PLoS ONE 7, e50568 (2012).

Wessells, K. R., Singh, G. M. & Brown, K. H. Estimating the global prevalence of inadequate zinc intake from national food balance sheets: effects of methodological assumptions. PLoS ONE 7, e50565 (2012).

Wuehler, S. E., Peerson, J. M. & Brown, K. H. Use of national food balance data to estimate the adequacy of zinc in national food supplies: methodology and regional estimates. Public Health Nutr. 8, 812–819 (2005).

Smith, M. R. et al. Global Expanded Nutrient Supply (GENuS) model: a new method for estimating the global dietary supply of nutrients. PLoS ONE 11, e0146976 (2016).

Beal, T. Y. et al. Global trends in dietary micronutrient supplies and estimated prevalence of inadequate intakes. PLoS ONE 12, e0175554 (2017).

Schmidhuber, J. et al. The Global Nutrient Database: availability of macronutrients and micronutrients in 195 countries from 1980 to 2013. Lancet Planet. Health 2, e353–e368 (2018).

GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 393, 1958–1972 (2019).

Khatibzadeh, S. et al. A global database of food and nutrient consumption. Bull. World Health Organ. 94, 931–934 (2016).

Miller, V. et al. Global Dietary Database 2017: data availability and gaps on 54 major foods, beverages and nutrients among 5.6 million children and adults from 1220 surveys worldwide. BMJ Glob. Health 6, e003585 (2021).

Ritchie, H., Reay, D. S. & Higgins, P. Beyond calories: a holistic assessment of the global food system. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2, 57 (2018).

Ritchie, H., Reay, D. S. & Higgins, P. Quantifying, projecting, and addressing India’s hidden hunger. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2, 11 (2018).

Ritchie, H., Reay, D. & Higgins, P. Sustainable food security in India—domestic production and macronutrient availability. PLoS ONE 13, e0193766 (2018).

Wood, S. A. et al. Trade and the equitability of global food nutrient distribution. Nat. Sustain. 1, 34–37 (2018).

Smith, N. W. et al. Use of the DELTA model to understand the food system and global nutrition. J. Nutr. 151, 3253–3261 (2021).

Geyik, O., Hadjikakou, M. & Bryan, B. A. Spatiotemporal trends in adequacy of dietary nutrient production and food sources. Glob. Food Secur. 24, 100355 (2020).

Geyik, O. et al. Does global food trade close the dietary nutrient gap for the world’s poorest nations? Glob. Food Secur. 28, 100490 (2021).

Del Gobbo, L. C. et al. Assessing global dietary habits: a comparison of national estimates from the FAO and the Global Dietary Database. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 101, 1038–1046 (2015).

Vos, T. et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1204–1222 (2020).

Rickard, A. P. et al. An algorithm to assess intestinal iron availability for use in dietary surveys. Br. J. Nutr. 102, 1678–1685 (2009).

Hambidge, K. M. et al. Zinc bioavailability and homeostasis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 91, 1478S–1483S (2010).

Chepeliev, M. Incorporating nutritional accounts to the GTAP Data Base. J. Glob. Econ. Anal. 7, 1–43 (2022).

Sun, L., Kwak, S. & Jin, Y.-S. Vitamin A production by engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae from xylose via two-phase in situ extraction. ACS Synth. Biol. 8, 2131–2140 (2019).

Loots, Du. T., Lieshout, M. V. & Lachmann, G. Sodium iron (III) ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid synthesis to reduce iron deficiency globally. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 61, 287–289 (2007).

Kołodziejczak-Radzimska, A. & Jesionowski, T. Zinc oxide—from synthesis to application: a review. Materials 7, 2833–2881 (2014).

Vitamin Angels. How to give vitamin A to children 6–59 months. Vitamin Angels https://www.vitaminangels.org/assets/content/uploads/OneSheetVASChildrenINTL_ENG_20170308.pdf (2021).

Bell, W., Lividini, K. & Masters, W. A. Global dietary convergence from 1970 to 2010 altered inequality in agriculture, nutrition and health. Nat. Food 2, 156–165 (2021).

Fanzo, J. & Davis, C. Can diets be healthy, sustainable, and equitable? Curr. Obes. Rep. 8, 495–503 (2019).

Finaret, A. B. & Masters, W. A. Beyond calories: the new economics of nutrition. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 11, 237–259 (2019).

Neumann, C., Harris, D. M. & Rogers, L. M. Contribution of animal source foods in improving diet quality and function in children in the developing world. Nutr. Res. 22, 193–220 (2002).

Willett, W. et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 393, 447–492 (2019).

Adesogan, A. T. et al. Animal source foods: sustainability problem or malnutrition and sustainability solution? Perspective matters. Glob. Food Secur. 25, 100325 (2020).

Bouis, H. E., Saltzman, A. & Birol, E. in Agriculture for Improved Nutrition: Seizing the Momentum (eds Fan S. et al.) 47–57 (CABI, 2019).

Neidecker-Gonzales, O., Nestel, P. & Bouis, H. Estimating the global costs of vitamin A capsule supplementation: a review of the literature. Food Nutr. Bull. 28, 307–316 (2007).

UNICEF. Coverage at a crossroads: new directions for vitamin A supplementation programmes. UNICEF https://data.unicef.org/resources/vitamin-a-coverage/ (2018).

UNICEF. Vitamin A deficiency. UNICEF https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/vitamin-a-deficiency/ (2021).

Mkambula, P. et al. The unfinished agenda for food fortification in low-and middle-income countries: quantifying progress, gaps and potential opportunities. Nutrients 12, 354 (2020).

Meijaard, E. et al. The environmental impacts of palm oil in context. Nat. Plants 6, 1418–1426 (2020).

Otero, G. et al. The neoliberal diet and inequality in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 142, 47–55 (2015).

Popkin, B. M. in Emerging Societies—Coexistence of Childhood Malnutrition and Obesity Vol. 63 (ed. Kalhan, S. C.) 1–14 (Karger, 2009).

Haddad, L. et al. Food Systems and Diets: Facing the Challenges of the 21st Century 2–134 (Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition, 2016).

Gashu, D. et al. The nutritional quality of cereals varies geospatially in Ethiopia and Malawi. Nature 594, 71–76 (2021).

The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction (FAO, 2019).

United Nations Environment Programme. Food Waste Index Report 2021 (UNEP, 2021).

Global Food Losses and Food Waste—Extent, Causes and Prevention (FAO, 2011).

Food loss and waste database. FAO www.fao.org/platform-food-loss-waste/flw-data/en/ (2021).

Fiedler, J. L. & Lividini, K. Monitoring population diet quality and nutrition status with household consumption and expenditure surveys: suggestions for a Bangladesh baseline. Food Sec. 9, 63–88 (2017).

Joy, E. J. M. et al. Dietary mineral supplies in Malawi: spatial and socioeconomic assessment. BMC Nutr. 1, 1–25 (2015).

Willett, W. in Nutritional Epidemiology (eds Hofman, A. et al.) 34–48 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2012).

Beal, T. Y. et al. Differences in modelled estimates of global dietary intake. Lancet 397, 1708–1709 (2021).

US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Research Service, Nutrient Data Laboratory. Food data central download data. USDA https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/ (2018).

FAO/IZiNCG. FAO/INFOODS/IZiNCG Global Food Composition Database for Phytate Version 1.0 - PhyFoodComp 1.0 (FAO, 2018).

Hallberg, L. & Hulthén, L. Prediction of dietary iron absorption: an algorithm for calculating absorption and bioavailability of dietary iron. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 71, 1147–1160 (2000).

FAOSTAT. Data: food balance (FAO, 2021); http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data

UN DESA (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs): world population prospects 2019 (UN, 2019); https://population.un.org/wpp/

Data: World Bank country and lending groups (The World Bank, 2021); https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

Data: The World Bank Atlas method—detailed methodology (The World Bank, 2021); https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/378832-what-is-the-world-bank-atlas-method

FAOSTAT. Data: supply utilization accounts (FAO, 2021); http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data

Economic statistics: introduction to CPC (UNSD, 2021); https://unstats.un.org/unsd/classifications/Econ/cpc

Central product classification (CPC) version 2.1 (UNSD, 2015); https://unstats.un.org/unsd/classifications/unsdclassifications/cpcv21.pdf

Central product classification (CPC) version 2.1 (UNSD, 2018); https://unstats.un.org/unsd/classifications/unsdclassifications/COICOP_2018_-_pre-edited_white_cover_version_-_2018-12-26.pdf

FANTA. Minimum dietary diversity for women: a guide for measurement. FAO https://www.fao.org/3/i5486e/i5486e.pdf (2016).

Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc (National Academy of Medicine, 2001).

FAOSTAT (FAO, 2021); http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#definitions

Handbook of fishery statistical standards. FAO/CWP http://www.fao.org/cwp-on-fishery-statistics/publications/otherdocuments/en/ (2004).

FishStatJ—software for fishery and aquaculture statistical time series (FAO, 2019); http://www.fao.org/fishery/statistics/software/fishstatj/en

Vincent, A. et al. FAO/INFOODS Food Composition Table for Western Africa (2019) User Guide & Condensed Food Composition Table (FAO, 2019).

OSU Extended Campus. CSS 330 world food crops: unit 16—cassava, sweetpotato, and yams (Oregon State Univ., 2021); https://oregonstate.edu/instruct/css/330/eight/Unit16Notes.htm

Gold, I. L. et al. in Palm Oil Ch. 10, 275–298 (AOCS Press, 2012).

Nutrient Data Laboratory. USDA national nutrient database for standard reference, release 28 (slightly revised). USDA http://www.ars.usda.gov/nea/bhnrc/mafcl (2016).

Weights, measures and conversion factors for agricultural commodities and their products. USDA https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=41881 (1992).

Handbook of fishery statistics. FAO/CWP http://www.fao.org/cwp-on-fishery-statistics/publications/otherdocuments/en/ (1992).

Finnie, S. & Atwell, W. A. Wheat Flour 2nd edn (Am. Assoc. Cereal Chem., 2016).

Fiedler, J. L. et al. Maize flour fortification in Africa: markets, feasibility, coverage, and costs. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1312, 26–39 (2014).

Kajuna, S. Millet: Post-harvest Operations (eds D. Mejia & B. Lewis) (FAO, 2001).

The coffee guide: trade practices of relevance to exporters in coffee-producing countries (Int. Trade Centre, 2019); http://www.thecoffeeguide.org/coffee-guide/world-coffee-trade/conversions-and-statistics/

How much per cup: use this coffee to water ratio for perfect coffee (Coffeestylish, 2019); https://coffeestylish.com/how-much-coffee/

Tea 101: how to measure loose leaf tea for brewing (Teatulia, 2019); https://www.teatulia.com/tea-101/how-to-measure-loose-leaf-tea-for-brewing.htm

Fairtrade standard for cocoa: explanatory note (Fairtrade Am. 2019); http://fairtradeamerica.org/resources%20library/standards/cocoa%20standards

Global Food Losses and Food Waste—Extent, Causes and Prevention (FAO, 2011)

Gustafsson, J. et al. The methodology of the FAO study: global food losses and food waste—extent, causes and prevention—FAO, 2011. SIK 57, 1–70 (2013).

Nutrient Data Lab (2017). USDA table of nutrient retention factors, release 6. USDA Agric. Res. Serv. https://doi.org/10.15482/USDA.ADC/1409034 (2007).

Armah, S. M. et al. A complete diet-based algorithm for predicting nonheme iron absorption in adults. J. Nutr. 143, 1136–1140 (2013).

Hunt, J. R. Dietary and physiological factors that affect the absorption and bioavailability of iron. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 75, 375–384 (2005).

Tseng, M. et al. Adjustment of iron intake for dietary enhancers and inhibitors in population studies: bioavailable iron in rural and urban residing Russian women and children. J. Nutr. 127, 1456–1468 (1997).

Conway, R. E., Powell, J. J. & Geissler, C. A. A food-group based algorithm to predict non-heme iron absorption. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 58, 29–41 (2007).

Miller, L. V., Krebs, N. F. & Hambidge, K. Michael A mathematical model of zinc absorption in humans as a function of dietary zinc and phytate. J. Nutr. 137, 135–141 (2007).

Estimating the number of pregnant women in a geographic area. CDC https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/emergency/pdfs/PregnacyEstimatoBrochure508.pdf (2016).

Singh, S. et al. Abortion worldwide 2017: uneven progress and unequal access. Guttmacher Inst. https://clacaidigital.info/bitstream/handle/123456789/1114/Abortion%20worldwide%202017.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y (2018).

Sedgh, G., Singh, S. & Hussain, R. Intended and unintended pregnancies worldwide in 2012 and recent trends. Stud. Fam. Plann. 45, 301–314 (2014).

Boss, M., Gardner, H., & Hartmann, P. Normal human lactation: closing the gap. F1000Research https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6013763/pdf/f1000research-7-15731.pdf (2018).

Dietary Reference Values for Nutrients Summary Report 14 (EFSA, 2017); www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2017_09_DRVs_summary_report.pdf

Download data Glob. Diet. Database https://www.globaldietarydatabase.org/data-download (2021).

UIA world country boundaries (ArcGIS, 2021); https://hub.arcgis.com/datasets/UIA::uia-world-countries-boundaries/about

Fiedler, J. L. et al. Identifying Zambia’s industrial fortification options: toward overcoming the food and nutrition information gap-induced impasse. Food Nutr. Bull. 34, 480–500 (2013).

EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for zinc. EFSA J. 12, 3844 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted as part of K.L.’s doctoral dissertation, under the advisement of W.A.M. We thank the other members of K.L.’s dissertation committee for their guidance: J. Coates, B. Rogers and M. Zeller. We are also grateful to M. R. Smith for his input and feedback on earlier versions of this study. This research was supported by funding for K.L. from the Wellcome Trust (grant number 210794/Z/18/Z).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.A.M. and K.L. conceived the overall study. K.L. assembled the data and developed the model code for the analysis. K.L. drafted the manuscript, and W.A.M. reviewed and edited the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Food thanks Edward Joy, Bhavani Shankar and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–9, Tables 1–4 and Formulas 1–22.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lividini, K., Masters, W.A. Tracing global flows of bioactive compounds from farm to fork in nutrient balance sheets can help guide intervention towards healthier food supplies. Nat Food 3, 703–715 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-022-00585-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-022-00585-w

This article is cited by

-

Nutrient accounting in global food systems

Nature Food (2022)