Key Points

-

This paper discusses the salient points that must be covered when taking a medical history for safe clinical practice.

-

A systematic approach to medical enquiry is provided.

-

A framework is provided for the systematic clinical description of lesions.

Abstract

All dental practitioners must be proficient at taking a medical history, examining a clothed patient and recognising relevant clinical signs. The general examination of a patient should take into account findings from the history. This paper does not attempt to address the detailed oral and dental examination carried out by dental practitioners but focuses on the holistic patient assessment – essential for safe patient management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dental practitioners are familiar with the component parts of a medical history. It is important that all patients have a comprehensive medical history taken and that it is updated at regular intervals. In this paper the general principles of medical history taking are revised and relevant clinical signs in the clothed patient that may be a clue to underlying disease are discussed.boxed-text

Main components of a medical history

Presenting complaint

The presenting complaint may be expressed in the patient's own words if this is felt to express the problem in the best way. The information presented is then summarised by the clinician.

History of presenting complaint

A chronological approach should be employed to obtain a history of the presenting complaint. As a minimum, the history of presenting complaint should include the following:

-

When the problem/condition first started

-

The overall duration and progression of the problem, including whether it is episodic or constant

-

The nature of any symptoms (see below)

-

Any systemic signs or symptoms such as fever

-

Previous treatments, their success or failure

-

Previous practitioners seen regarding the same or related condition(s).

In dental practice, the presenting complaint is sometimes one of pain. It is useful to have a generic scheme of questions to assess the nature and severity of a patient's pain. Such a scheme is shown in Table 1.

Past medical history

There are various ways of taking this part of the history. It is often useful to start with generic questioning regarding major systems such as the cardiovascular or respiratory systems. Questioning should then focus on specific disorders such as asthma or other respiratory disorders, diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, hypertension, hepatitis or jaundice. Problems with the arrest of haemorrhage are worth specific enquiry. Any positive responses should be followed up by an assessment of the severity of the disorder, treatments used and their efficacy.

It is essential to ask about any known allergies and if a positive response is obtained, to enquire about the nature of such an allergy.

Medications and drugs

All medications or drugs that the patient may be taking should be included.1 This should include 'recreational' drugs and homeopathic or other over-the–counter substances. In addition it is pertinent to ask about inhaled or topical medicines as many patients do not consider these as 'drugs'. Concurrent drug therapy can impact upon orofacial signs and symptoms, the safe provision of dental treatment and the use of other medications.

Recreational drugs and complementary medications

The use of drugs of abuse is common and dentists should have a working knowledge of the implications for patients who say that they are using these. Cannabis has a sympathomimetic action and in theory could exacerbate the systemic effects of adrenaline in dental local anaesthetics.2 Heroin and methadone are opioid drugs, the latter being used in rehabilitation programmes.3 Oral methadone has a high sugar content that can cause rampant caries. Heroin can cause thrombocytopenia with potential knock-on effects in terms of haemostasis. Some of those addicted to heroin have a low threshold for pain. The drug also interacts with preparations that dentists may prescribe.4 The absorption of paracetamol and orally administered diazepam is delayed and reduced due to delayed gastric emptying. Carbamazepine reduces serum methadone levels and methadone increases the effects of tricyclic antidepressants.

Patients who abuse cocaine are subject to increased risk of the effects of ischaemia leading to loss of tissue. Testing the 'quality' of the drug by rubbing on the oral mucosa to test depth of anaesthesia may lead to loss of gingivae and alveolar bone. An increased incidence of dental caries may be seen if cocaine is bulked out with carbohydrates. As with heroin, thrombocytopenia may be seen. Like cannabis, cocaine has a sympathomimetic action.

Amphetamines and ecstasy may produce thrombocytopenia. Concomitant use with monoaminoxidase inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants can precipitate a hypertensive crisis.

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) is a hallucinogenic drug. Such drugs increase the incidence of bruxism and patients taking it may present with temporomandibular joint dysfunction. Dentists should be aware that stressful situations may cause flashbacks and panic attacks in these patients.

In more recent years, the problem of solvent abuse has reached the headlines. A reduction in the dose of adrenaline containing local anaesthetics is recommended in those who chronically abuse solvents as such agents can sensitise the myocardium to the actions of the catecholamine. Solvent abuse also increases the risk of convulsions and status epilepticus may occur.

Some patients may abuse anabolic steroids and performance enhancers, which may precipitate increased carbohydrate consumption with its inevitable effects on the dentition. The systemic effects of adrenaline in dental local anaesthetics can be exacerbated by the sympathomimetic effects of certain anabolic steroid drugs. As with many other illicit drugs, anabolic steroids may interfere with blood clotting.

Complementary therapies are often used by patients. It is important to remember potential interactions with prescription drugs, some of which may be prescribed by dental practitioners. Some of the more common interactions are shown in Table 2.

Past dental history

The past dental history will assume different forms depending on the patient's previous exposure to dental treatment. It is clearly relevant to find out whether a patient is a regular attender and of their previous experience of dental treatment and its nature. The previous use of local anaesthetic agents and any associated problems can be checked. If not covered by the previous history, adverse events such as post-extraction haemorrhage may be highlighted at this point.

Social history/family history

The social history is often neglected but it is an important part of the comprehensive assessment of a patient. It may directly influence treatment or the way it is delivered. As a minimum, enquiry should be made of the patient's smoking status and alcohol consumption, and if positive these should be quantified. The system of units for measuring alcohol consumption is summarised in Table 3. The patient's occupation (or previous occupation if retired) is also important.

Finally, information concerning the patient's home circumstances is significant. It is particularly important to find out whether a patient lives with another 'competent' adult, as in cases of intravenous sedation or day case general anaesthesia, the patient should be looked after for 24 hours following the procedure by such an adult.

Disorders with a genetic origin should be recorded.

Psychiatric history

The psychiatric history is not included as routine but may be relevant in some cases as discussed in a previous paper in this series.5

In hospital practice, a body systems' review is undertaken after the preliminary history. While it is recognised that this would rarely be used in mainstream dental practice, it is discussed here to highlight its effectiveness on assessing various systems from a medical standpoint.

General enquiry

It is worth starting with a series of general questions that may highlight relevant conditions that otherwise may be missed from the more specific systems' review.6 Such findings include:

-

Appetite, weight loss

-

Lethargy or fatigue

-

Fevers

-

The presence of any lumps, bumps or swellings

-

The presence of skin rashes.

Cardiovascular system

-

Chest pain (bear in mind other potential causes) – Table 4. Does the chest pain occur at rest or after exertion – how much exertion?

Table 4 A differential diagnosis of chest pain -

Dyspnoea (remember potential respiratory causes either coexisting or in isolation). Does breathlessness occur at rest/on exertion?

-

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea (waking from sleep feeling breathless) or orthopnoea (breathlessness on lying flat)

-

Palpitations

-

Prosthetic/replacement heart valves

-

History of rheumatic fever and/or infective endocarditis

-

Claudication pains and what is required to precipitate them.

Respiratory system

-

Breathlessness/wheeziness

-

The presence or otherwise of a cough, its duration and whether productive or not

-

Haemoptysis (coughing up of blood)

-

Sputum production

-

History of known respiratory disorders and exacerbations – note the degree of success of treatment (judged by control/relief of symptoms).

Gastrointestinal system

-

Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing)

-

Odynophagia (pain on swallowing)

-

Indigestion, nausea or vomiting

-

Haematemesis (vomiting blood)

-

Change in bowel habit

-

Liver problems.

Neurological system

-

Any history of fits, faints or blackouts

-

Headache or facial pain

-

Disturbance in motor function or sensation

-

Muscle wasting, weakness or fasciculation

-

Disorders of coordination.

Musculoskeletal system

-

Pain/swelling/stiffness of joints

-

Gait (bear in mind potential neurological problems)

-

Joint prostheses

-

Locomotor and manual impairment secondary to musculoskeletal disorders.

Genitourinary system

Usually the genitourinary system need not be enquired about in any detail. Patients with repeated urinary tract infections may be taking antibiotics, which could be of relevance.

Examination of the clothed patient

It is important to remember to take a holistic approach to the patient and make relevant general observations. If a patient looks ill they probably are! Is the patient of average weight or are they cachectic or obese?

A subjective assessment of the patient's level of alertness is important and differentiation made between an acute confusional state and a chronic condition, for example the chronic confusion in a patient with dementia. Potential causes of acute confusion are summarised in Table 5.

Note should also be made of the patient's complexion, for example are they pale, flushed or cyanotic? Are they breathless, either at rest or after minimal exertion? Clearly positive findings are important but may not be diagnostic. It is more important to gauge the overall 'condition' of the patient in order to assess their level of suitability for treatment in a particular clinical environment.

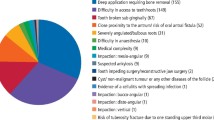

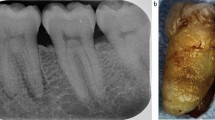

The hands and face are good mirrors of general health problems in dental patients. There are several signs that can be observed in the hands. The overall appearance of the hands should be noted, together with abnormalities of the skin, nails and muscles. Palmar erythema can be seen in pregnancy, some patients with liver problems and rheumatoid arthritis. Swollen proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints (nearest the knuckles) suggest rheumatoid arthritis, particularly in conjunction with ulnar deviation of the hands (Fig. 1). Swelling of the distal interphalangeal joints (DIP) suggests osteoarthritis. The nails can show a variety of abnormalities, which vary according to the underlying aetiology. In the patient with psoriasis, for example, the fingernails may be pitted. Clubbing of the fingers (Fig. 2) may indicate disease processes in various systems. In this condition, there is a loss of the angle between the nail and nail bed leading to a fingernail with an exaggerated longitudinal curvature. Potential causes of finger clubbing are shown in Table 6.

The hand may also show signs of contraction of the palmar fascia, so-called Dupuytren's Contracture as shown in Figure 3. The little and ring fingers in this condition remain flexed even when the hand is passive. The aetiology is not known, but the condition is sometimes associated with alcoholism.

The patient's complexion may give clues in relation to underlying systemic problems. Although jaundice may be observed in the skin, the best place to examine for the yellow discolouration is in the sclera of the eyes. The clinical and metabolic syndrome seen in chronic kidney disease (uraemia) may also impart a yellowish discolouration to the skin. Xanthelasma may be observed on the eyelids (Fig. 4). These lesions represent fatty deposits, which signify hyperlipidaemia. The so-called malar flush of mitral stenosis or the butterfly rash in systemic lupus erythematosus may be observed. Cyanosis may be observed. If the cyanosis is of the central type the tongue will acquire a bluish colour. Peripheral cyanosis may be seen in the nail beds and is caused either by vascular insufficiency or peripheral vasoconstriction in cold conditions.

Although not routinely measured in dental practice, practitioners should be aware of the vital signs and their normal values. Oxygen saturation is not considered to be a formal part of the vital signs assessment but is increasingly being considered as a fifth vital sign. The vital signs and normal values are given in Table 7.

Of all the vital signs, one of the most common that could be measured by dental practitioners is the radial pulse. It is useful to have a working knowledge of the more common causes of tachycardia and bradycardia and these are listed in Table 8.

It is important that practitioners have a generic 'check list' that enables a comprehensive description of lesions to be carried out. Table 9 lists the criteria that should be established when examining any lump.

A similar scheme may be adopted to describe an ulcer. This scheme is summarised in Table 10.

Conclusions

Much of the medical assessment of a patient is derived from the history. It is important, however, that dental practitioners have a sound knowledge of some of the more common signs that may be observed in the clothed patient, which can signal underlying general health conditions. Some underlying conditions will be of direct relevance to the safe management of dental patients.

References

Longmore M, Wilkinson I, Davidson E, Foulkes A, Mafi A . Oxford handbook of clinical medicine. 8th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Greenwood M, Seymour R A, Meechan J G . Textbook of human disease in dentistry. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

Meechan J G, Seymour R A . Drug dictionary for dentistry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

British National Formulary. About the BNF. Online information available at http://www.bnf.org/bnf/org_450041.htm (accessed March 2014).

Brown S, Greenwood M, Meechan J G . General medicine and surgery for dental practitioners paper 5: psychiatric Disorders. Br Dent J 2010 209: 11–16.

Scully C . Medical problems in dentistry. 6th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingstone, 2010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Greenwood, M., Meechan, J. General medicine and surgery for dental practitioners: part 1. History taking and examination of the clothed patient. Br Dent J 216, 629–632 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.446

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.446