Key Points

-

Highlights that the prevalence of dental discomfort during a dive among recreational scuba divers is high.

-

Suggests that scuba diving instructors may be more likely to experience oro-facial pain during a dive.

-

Demonstrates that molar teeth were most commonly involved in an episode of diving related dental pain.

Abstract

Objective To determine the prevalence of dental symptoms in recreational scuba divers and describe the distribution of these symptoms on the basis of diver demographics, diving qualifications and dive conditions during the episode of dental pain.

Design A survey was designed and distributed through online social media platforms dedicated to scuba diving. A convenience sample of 100 recreational divers was obtained by this method.

Main outcome measures The outcome measures of interest were: diver demographics, diving characteristics (level of certification, number of dives completed), occurrence of dental problems during a dive, and details of the episode.

Results Forty-one percent of the respondents experienced dental symptoms during a dive. Barodontalgia was the most frequently experienced dental symptom during a dive.

Conclusion Within the limits of the small sample size and online method of recruitment, the findings of this study suggest that a high proportion of recreational divers may experience dental symptoms during a dive. It would be meaningful to ensure that dental decay and damaged restorations are addressed before a dive and that the mouthpiece design be evaluated in case of complaints of temporomandibular discomfort during a dive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

SCUBA (self-contained underwater breathing apparatus) diving is gaining popularity as a recreational sport. There is an entire industry of training and certifying agencies, dive equipment marketing, dive travel and insurance that has developed around this sport. Between 1999–2008 more than 11.5 million divers were certified by the Professional Association of Diving Instructors in the United States.1 Diving certifications classify divers by number of dives and maximal dive depth for each level of certification. For example, open water divers are usually restricted to 18 meters, while advanced open water divers can descend to depths up to 30 m. Dive masters are required to have logged a minimum of 40 dives, while dive instructors need to have completed 100 dives to be certified.2

To reduce the risks of accidents during a dive, diving equipment needs to meet stringent criteria to be considered safe. Divers are trained to follow specific protocols in case of equipment failure. To reduce diving hazards, measures such as a controlled rate of ascent and descent, use of dive computers that monitor the dive profile, and diving with an extra air regulator are followed. Additionally, certifying agencies require divers to meet a specific standard of medical fitness before certification. However, there are no dental health prerequisites for recreational dive certification. Considering that the air supply regulator is held in the mouth, any disorder of the oral cavity can potentially increase the diver's risk of injury.

Traumatic injuries to the orofacial structures in scuba divers may occur due to pressure fluctuations and constant jaw clenching. This effect has been referred to as 'divers mouth syndrome',3,4 and ranges in severity from dry mouth to 'odontocrexis' or tooth fracture.5 Other symptoms reported are barodontalgia or tooth squeeze6 which is pain or injury to teeth due to changes in the pressure gradient,7 discomfort and pain in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ),8 loosening of dental fillings and restorations9 and injury to oral soft tissue due to improper mouthpiece design.10

Most studies assessing the prevalence of dental symptoms in divers have investigated military divers or professional divers with extensive training and long diving experience.11 For example, in a study of 1,317 French military divers, Gunepin et al.6 reported that 7.3% experienced barodontalgia. Fifteen percent of 520 professional divers and caisson workers surveyed by Zanotta et al.11 experienced pressure related dental symptoms. Studies5,12 in recreational divers have shown a slightly higher prevalence of barodontalgia. Specifically, Yousef et al.5 noted the prevalence of TMJ symptoms and orofacial pain ranging from 4% to 52% among 163 divers in Saudi Arabia. Interestingly, 90% of the divers in this study were male. In a similar study,12 44% of 125 Australian divers suffered from orofacial pain during diving. The majority of divers in this study were in their third to fourth decade of life. It is likely that the occurrence of dental symptoms is higher among recreational divers compared to military and professional divers. This may be due to the greater access that military and professional divers may have to physicians with expert knowledge in diving medicine.6

The aim of this pilot study was to evaluate the prevalence of dental symptoms in recreational scuba divers and determine the distribution of these symptoms on the basis of diver demographics, diving qualifications and dive conditions during the episode of dental pain.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the University of Rochester, Research Subject Review Board (RSRB#00060,619). The survey was pilot tested on a group of ten divers to evaluate the format and content of questions and to improve the validity of the survey. The survey took approximately ten minutes to complete. The data was collected from 30 March 2014 to 24 August 2014.

A convenience sample of subjects was obtained by posting the survey to social media platforms (Facebook and online scuba diving forums) and referral (word-of-mouth by study personnel and their networks, professional colleagues, and participants who had already completed the survey). Only certified scuba divers, 18 years and older were included. Divers suffering from a cold during the episode of pain and divers taking decongestant medication to treat a cold were excluded.

A descriptive 20-question survey with both multiple choice options and open-ended responses was used to assess the prevalence of dental symptoms in divers. The topics addressed were: demographics (age, gender), diving characteristics (level of certification, number of dives completed), occurrence of dental problems during a dive, and details of the episode (type of problem, teeth affected, and safety stop performed). The survey was designed and administered through the 'Forms' function of Google Docs. The responses were automatically coded into the 'Sheets' function of Google Docs. After filling in demographic information, an initial screening question for pain was asked. Respondents who reported an occurrence of orofacial pain during a dive were prompted to answer a series of questions describing the painful incident. For respondents who did not experience pain, the survey ended with the report of no incident of orofacial pain during a dive.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistics were reported for demographic variables. For continuous variables, such as age, the means and standard deviations were calculated. For categorical variables, the frequencies for different categories were reported. The prevalence of dental symptoms was calculated. Multiple polytomous logistic regression and Fisher's exact test were used to study the effects of demographic covariates on the probabilities of dental symptoms among divers of different certification levels with statistically significant level at P <0.05.

Results

One hundred and seventeen responses were received and data from 100 respondents who fulfilled the eligibility criteria was analysed. The age range of the respondents was 18 years to 65 years and the mean age was 39.08 years. Forty percent were female and 60% were male. Sixteen percent of respondents were certified at the basic level of recreational diving – open water diver (OWD), 30% were advanced open water divers (AWD), 9% were certified as rescue divers (RD) within recreational diving, 16% were certified dive master (DM) and 29% were instructor level divers (DI).

The occurrence of dental symptoms during a dive among recreational scuba divers was reported as 41%. The age range was 19 years to 58 years and the mean age was 38.6 years. Of the divers reporting dental symptoms, 49% (N = 20) were female and 51% (N = 21) were male. The distribution of dental problems according to divers' level of certification was 22% in OWD, 19% in AWD 5% in RD, 15% in DM and 39% in DI. Dental symptoms began during descent in 34% of the population, during ascent in 24% of the population and 42% experienced pain during both ascent and descent. Table 1 shows the prevalence of pain according to the level of certification and safety stop. For divers experiencing persistent pain, 23% (N = 5) were OWD, 18% (N = 4) were AWD, 5% (N =1) were RD, 14% (N = 9) were DM and 41% (N = 3) were DI. Only 12% of divers who experienced pain did not make a safety stop, and 5% of them experienced persistent pain. Out of the remaining 88% who made the safely stop, 41% experienced persistent pain.

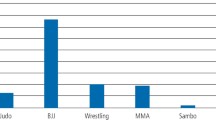

Table 2 describes the distribution of pain according to type of problem, teeth affected and time of onset of pain. Forty-two percent (N = 17) reported tooth squeeze (barodontalgia) as the type of problem, 24% (N = 10) experienced pain from holding the regulator too tightly, 22% (N = 9) reported jaw pain, 5% (N = 2) noted loosening of crowns placed on teeth, 5% (N = 2) reported pain in the gums, 2% (N = 1) reported a broken dental filling. Among the divers who experienced dental symptoms, 54% had a tooth cavity or a previous filling, while 46% had no cavities or fillings. The distribution of pain according to presence of cavity and/or filling is illustrated in Figure 1. It was found that 39% of females and 44% of males in this study who experienced dental symptoms had not undergone recent dental treatment, while 10% of females and 7% of males who underwent dental treatment less than a month ago experienced dental symptoms.

Fisher's analysis showed no significant difference among the five levels of diving certification in the type of problems (P = 0.08), teeth most frequently affected (P = 0.40) and time of onset of pain (P = 0.47). There was also no significant difference between males and females in the type of problems (P = 0.57).

The exact logistic regression showed that there was no significant difference on pain persistence by the level of certification (P = 0.96) or by the safety stop (P = 1.0).

Discussion

The prevalence of dental symptoms among recreational divers in this pilot survey was found to be 41% similar to previous studies5,12 in non-military divers. The results support the hypothesis that the frequency of dental problems is higher in recreational divers compared to military and professional divers.6,9,11 This may be attributed to regular dental follow up in military divers, and the emphasis on maintaining good oral health among this population.9 In contrast, recreational divers who represent a section of the general population may have variable access and utilisation of dental services.13,14

There was an even distribution of respondents according to gender in this study. This is in marked contrast to previous surveys which had a predominance of male divers.15,16,17 The prevalence of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders is higher in females18 in the general population and this trend has also been reported among female divers.4,15,19 Interestingly, the incidence of jaw pain was distributed equally among the genders in this study. This is in contrast to the findings of Aldridge et al.19 who noted that jaw joint pain during diving was similar to that experienced in daily life. Factors such as clenching on the mouthpiece due to temperature changes in the water or maintaining the proper position of an ill-fitting regulator in the mouth could be responsible for TMJ pain.20 Additionally, prolonged forward positioning of the mandible to adapt to the mouthpiece may precipitate jaw joint discomfort. It has been suggested that extending the interdental bite platform of the mouthpiece up to the molars could reduce the mechanical overloading on the TMJ4,21 in divers. Therefore, although females in the general population are more likely to suffer from TMJ disorders,22 mouthpiece design may be a critical factor which may contribute to TMJ pain in divers. In the present report almost one-fourth of the divers experienced TMJ pain associated with diving. Roydhouse23 interviewed 322 divers and observed a similar prevalence of TMJ pain. Interestingly, jaw pain was the most frequent problem experienced by open water divers who represent the most basic level of certification. This is similar to the finding by Hirose et al.24 who reported that significantly more beginners experienced jaw pain and persistent discomfort after diving. The inexperience of novice divers in maintaining the regulator intraorally and simultaneously sustaining mouth breathing could contribute to this jaw fatigue and pain.

More than half of the teeth affected by pain were molars. It is well known that molars are most susceptible to decay and most frequently restored.25,26 It is possible that air trapped beneath damaged restorations or within decayed teeth could expand and contract abnormally in the course of a dive, resulting in dental pain. This explanation is supported by a study by Calder et al.27 that demonstrated the negative effect of changing pressure on teeth with damaged fillings. It is worthwhile to mention the relation between maxillary sinus barotrauma and maxillary tooth pain. The literature shows that air entrapped within a blocked sinus can refer pain to maxillary molar teeth. This phenomenon has been described as 'indirect barodontalgia'.7,28 In order to distinguish between direct barodontalgia (caused by pulpal disease with or without periradicular involvement) and indirect barodontalgia, this study excluded all respondents who were suffering from a cold when the episode of diving-related dental pain occurred. Moreover, divers on decongestant medications were excluded to control for the effect of indirect barodontalgia.

For direct barodontalgia, the onset of dental symptoms was variable and almost 40% of divers experienced pain during both the ascent and descent phases of the dive. Zadik28 in a review on barodontalgia related the time of onset of pain with a definite type of tooth pathology. Specifically, persistent pain on ascent and descent suggests periradicular pathology, irreversible pulpitis would present as a momentary sharp pain on ascent, while a dull throbbing pain on decent would indicate a necrotic pulpitis. Further clinical investigations in the respondents of this survey would be needed to determine if the time of onset of pain was co-relatable to these criteria.

The present results report a higher prevalence of barodontalgia (41%) compared with previous studies.5,12,15 This could be because almost one third of the respondents were instructor level divers. It is hypothesised that dive instructors are more prone to barometric trauma as they spend greater time at shallower depths, assisting inexperienced divers with equalisation of the ears and sinuses. Underwater pressure increases in a linear manner with depth.29 The maximum pressure variation during descent into a dive occurs in the first ten metres where pressure doubles from 1 bar atmosphere at the surface to 2 bar atmosphere at ten metres. The relation between pressure fluctuation and dental health in divers has been studied by Goethe et al.30 who evaluated the teeth of frogmen, naval divers and submariners over a period of ten years. They found that frogmen who spent greater time at shallower depths compared to naval divers, showed the highest deterioration of teeth at the ten year follow up, in spite of having better dental health than naval divers and submariners at baseline. The results of the present study show a similar correlation. Although instructors were the second largest group surveyed, they had the highest prevalence of dental symptoms associated with diving as well as persistence of these symptoms after diving.

It is pertinent to discuss the influence of the safety stop on the persistence of dental pain following a dive. The purpose of this halt at five metres for three minutes at the end of the dive is to allow the nitrogen to leave the blood in a controlled manner, reducing the likelihood of decompression sickness.31 It is tempting to speculate that air trapped beneath a restoration will expand more uniformly and escape at the time of the safety stop. However, in the present study there was no link between persistence of pain and performance of the safety stop. This is possibly due to the relatively small sample size of this study.

Apart from the small sample size, this study has a number of limitations. Firstly, as it was an online survey, the external validity of the respondents cannot be assessed.32,33 Although the survey was posted only to divers forums, it was not possible to ensure that non-divers responded. Secondly, information on dental status was self-reported. However, it is known that the validity of self-reported dental status is moderate,34,35,36 and the data could be more reliable if the divers were examined by a dentist or existing dental records could be obtained. Also, as some of the questions were open-ended, there was a variability in the responses received. For example, for the question regarding the teeth experiencing pain, there was no uniformity in the responses. Therefore, the responses were divided according to the tooth class affected, with an approximation of the answers in equivocal responses. Finally, racial and ethnic information was not recorded. It is well known that pain perception and tolerance varies depending on race and ethnicity.37,38 More descriptive future studies with a larger sample size and includ an oral examination are needed to overcome these limitations.

Conclusion

The results of this pilot survey show that for recreational divers, barodontalgia is most frequently experienced dental symptom during a dive. The distribution of jaw pain is similar among the genders, dive instructors may have a greater prevalence of orofacial symptoms during a dive and molars may be more painful as a result of the diving conditions. For the dentist treating the diver, it may be meaningful to record if any TMJ disorder exists or if the diver has experienced TMJ pain during a dive. It might be worthwhile to fabricate a customised mouthpiece for the patients' diving regulator to maintain a more comfortable and stable jaw position during the dive. Treatment of teeth with decay and damaged restorations might help reduce the likelihood of experiencing barotrauma.

References

Bureau UC . Parks, recreation, and travel: Participation in sports activity statistics: 1998, table no. 435. 1998. Available online at http://www.allcountries.org/uscensus/435_participation_in_selected_sports_activities.html. (accessed March 2016).

PADI. Professional Association of Diving Instructors course catalogue. Available online at http://www.padi.com/scuba-diving/padi-courses/course-catalogue/ (accessed March 2016).

Goldstein G R, Katz W . Divers mouth syndrome. N Y State Dent J 1982; 48: 523–525.

Hirose T, Ono T, Maeda Y . Influence of wearing a scuba diving mouthpiece on the stomatognathic system- considerations for mouthpiece design. Dent Traumatol 2015; 32: 219–224.

Yousef M K, Ibrahim M, Assiri A, Hakeem A . The prevalence of oro-facial barotrauma among scuba divers. Diving Hyperb Med 2015; 45: 181–183.

Gunepin M, Derache F, Blatteau J E, Nakdimon I, Zadik Y . Incidence and Features of Barodontalgia Among Military Divers. Aerosp Med Hum Perform 2016; 87: 137–140.

Kumar S, Kumar P S, John J, Patel R . Barotrauma: Tooth under pressure. J Mich Dent Assoc 2015; 97: 50–54.

Hobson RS . Temporomandibular dysfunction syndrome associated with scuba diving mouthpieces. Br J Sports Med 1991; 25: 49–51.

Gunepin M, Derache F, Dychter L, Blatteau J E, Nakdimon I, Zadik Y . Dental barotrauma in french military divers: Results of the POP Study. Aerosp Med Hum Perform 2015; 86: 652–655.

Grant S M, Johnson F . Diver's mouth syndrome: a report of two cases and construction of custom-made regulator mouthpieces. Dent Update 1998; 25: 254–256.

Zanotta C, Dagassan-Berndt D, Nussberger P, Waltimo T, Filippi A . Barodontalgias, dental and orofacial barotraumas: a survey in Swiss divers and caisson workers. Swiss Dent J 2014; 124: 510–519.

Jagger R G, Shah C A, Weerapperuma I D, Jagger D C . The prevalence of orofacial pain and tooth fracture (odontocrexis) associated with SCUBA diving. Prim Dent Care 2009; 16: 75–78.

Gaffar B O, Alagl A S, Al-Ansari A A . The prevalence, causes, and relativity of dental anxiety in adult patients to irregular dental visits. Saudi Med J 2014; 35: 598–603.

Srikandi T W, Carey S E, Clarke N G . Utilization of dental services and its relation to the periodontal status in a group of South Australian employees. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1983; 11: 90–94.

Koob A, Ohlmann B, Gabbert O, Klingmann C, Rammelsberg P, Schmitter M . Temporomandibular disorders in association with scuba diving. Clin J Sport Med 2005; 15: 359–363.

Roydhouse N . 1001 disorders of the ear, nose and sinuses in scuba divers. Can J Appl Sport Sci 1985; 10: 99–103.

Taylor DM, O'Toole K S, Ryan C M . Experienced scuba divers in Australia and the United States suffer considerable injury and morbidity. Wilderness Environ Med 2003; 14: 83–88.

Luther F . TMD and occlusion part II. Damned if we don't? Functional occlusal problems: TMD epidemiology in a wider context. Br Dent J 2007; 202: 38–39.

Aldridge R D, Fenlon M R . Prevalence of temporomandibular dysfunction in a group of scuba divers. Br J Sports Med 2004; 38: 69–73.

Rogoff A . Diving damage. J Am Dent Assoc 2010; 141: 15; author reply 15–16.

Hobson R S, Newton J P . Dental evaluation of scuba diving mouthpieces using a subject assessment index and radiological analysis of jaw position. Br J Sports Med 2001; 35: 84–88.

Manfredini D, Guarda-Nardini L, Winocur E, Piccotti F, Ahlberg J, Lobbezoo F . Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2011; 112: 453–462.

Roydhouse N . The jaw and scuba diving. J Otolaryngol Soc Aust 1977; 4: 162–165.

Hirose T, Ono T, Nagashima T, Nokubi T . The influence of scuba diving mouthpieces on the maxillo-oral system. J Sports Dent 2003; 5: 1–10.

Brazzelli M, McKenzie L, Fielding S et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of HealOzone for the treatment of occlusal pit/fissure caries and root caries. Health Technol Assess 2006; 10: iii–iv, ix-80.

Masood M, Masood Y, Newton J T . The clustering effects of surfaces within the tooth and teeth within individuals. J Dent Res 2015; 94: 281–288.

Calder I M, Ramsey J D . Ondontecrexis-the effects of rapid decompression on restored teeth. J Dent 1983; 11: 318–323.

Zadik Y . Barodontalgia. J Endod 2009; 35: 481–485.

Lynch J H, Bove A A . Diving medicine: a review of current evidence. J Am Board Fam Med 2009; 22: 399–407.

Goethe W H, Bater H, Laban C . Barodontalgia and barotrauma in the human teeth: findings in navy divers, frogmen, and submariners of the Federal Republic of Germany. Mil Med 1989; 154: 491–495.

Zadik Y, Drucker S . Diving dentistry: a review of the dental implications of scuba diving. Aust Dent J 2011; 56: 265–271.

Nikolaev VP . [A theoretical estimation of the safety of dives culminating in an uninterrupted lifting]. Biofizika 2010; 55: 145–153.

Lane T S, Armin J, Gordon J S . Online recruitment methods for web-based and mobile health studies: A review of the literature. J Med Internet Res 2015; 17: e183.

Frandsen M, Walters J, Ferguson S G . Exploring the viability of using online social media advertising as a recruitment method for smoking cessation clinical trials. Nicotine Tob Res 2014; 16: 247–251.

Gilbert G H, Litaker M S . Validity of self-reported periodontal status in the Florida dental care study. J Periodontol 2007; 78: 1429–1438.

Csikar J, Wyborn C, Dyer T, Godson J, Marshman Z . The self-reported oral health status and dental attendance of smokers and non-smokers. Community Dent Health 2013; 30: 26–29.

Ardila C M, Posada-Lopez A, Agudelo-Suarez AA . A multilevel approach on self-reported dental caries in subjects of minority ethnic groups: A cross-sectional study of 6440 Adults. J Immigr Minor Health 2016; 18: 86–93.

Plesh O, Adams S H, Gansky S A . Racial/Ethnic and gender prevalences in reported common pains in a national sample. J Orofac Pain 2011; 25: 25–31.

Morris M C, Walker L, Bruehl S, Hellman N, Sherman A L, Rao U . Race effects on conditioned pain modulation in youth. J Pain 2015; 16: 873–880.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ranna, V., Malmstrom, H., Yunker, M. et al. Prevalence of dental problems in recreational SCUBA divers: a pilot survey. Br Dent J 221, 577–581 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.825

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.825

This article is cited by

-

Effect of a hyperbaric environment (diving conditions) on adhesive restorations: an in vitro study

British Dental Journal (2017)

-

Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water...

British Dental Journal (2016)