Abstract

AIM: To explore the relationship between smoking and dieting in a cross-sectional nationally representative sample of young adolescents.

METHODS: Smoking was assessed by serum cotinine concentrations in 1132 adolescents aged 12–18 y enrolled in the NHANES III study. Information on adolescents' weight loss attempts were obtained by questionnaire. Normal weight was defined as a body mass index (BMI) less than the 85th percentile for age and gender. Overweight was defined as a BMI equal to or greater than the 85th percentile for age and gender. Nutritional intake was assessed with a 24 h recall and food frequency questionnaire.

RESULTS: There was a two-fold increase in smoking among normal-weight adolescent girls who reported trying to lose weight (23.7% vs 12.6%, P<0.01). In contrast, prevalence of smoking was similar among overweight adolescent girls who tried to lose weight compared to those who did not (15.8% vs 14.1%, P=0.76). Similar trends were observed in boys. However, overweight boys who were trying to lose weight were less likely to smoke than overweight boys who were not trying to lose weight (9.8% vs 24.5%, P<0.05). There were no differences in body weight, BMI, caloric intake or fat intake among smokers and non-smokers. However, smokers reported eating less fruit and vegetables compared to non-smokers, and were over five times more likely to drink alcohol compared to non-smokers (odds ratio: ≥1×/month, 5.28 (3.82–7.28), ≥4×/month, 5.29 (3.58–7.82).

CONCLUSION: Tobacco use is common among normal weight adolescents trying to lose weight. Tobacco use is also associated with a cluster of other unhealthy dietary practices in adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although it has been suggested that adolescents may use tobacco as a form of weight control, the prevalence of this practice is unknown. Ryan and colleagues have reported that adolescent Irish girls who report recent dieting are over twice as likely to smoke as adolescents who do not report weight loss attempts.1 In addition, data from Tomeo et al2 and French et al3 also suggest that smoking among girls was associated with almost a two-fold risk of dieting. In fact, the Expert Committee on the Evaluation and Treatment of Childhood Obesity recommends that smoking cessation should be one of the cornerstones of treating overweight children, along with improved parenting skills, reduced caloric intake and increased activity levels.4

Previous studies on the relationship between smoking and dieting have relied on self-reported smoking behavior in adolescents. While self-reported smoking behavior is generally considered a reliable measure of actual smoking in adolescents, biases may exist in the data depending on the setting that the information was obtained.5,6 In addition, previous studies have also not examined whether smoking was more prevalent among either normal-weight or overweight adolescents who were trying to lose weight or whether nutritional intake was actually different among smokers and non-smokers.

To address the association of dieting and adolescent smoking, data were analyzed from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, cycle III (NHANES III), a nationally representative sample of children and adults. Comprehensive data including weight, height, weight loss attempts, smoking habits, and serum cotinine levels allowed for analysis of the relationship of smoking to weight loss attempts in overweight and normal-weight adolescents. Data from both 24 h dietary recall and a food frequency questionnaire also allowed for the analysis of the relationship between smoking and nutritional intake among adolescents.

Methods

Sample

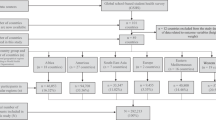

The National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey, Cycle III (NHANES III) is the seventh in a series of large national health examination surveys conducted in the United States since the 1960s. The first phase of NHANES III examined a nationally representative sample of children and adults between 1988 and 1991.Footnote 1 The sample included 1331 children aged 12–18. Weights and heights were available on over 99% of the children. Serum cotinine levels were available on 1132 of the adolescents (85% of eligible cohort).

Anthropometrics

Body weight and height were measured according to previously described methods.7 Reference body mass index (BMI) percentiles were derived from the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.8 This definition is in accordance with recommendations of the Expert Committee on Clinical Guidelines for Overweight in Adolescence9 and Expert Committee on Obesity Evaluation and Treatment.4 Normal weight was defined as a BMI (kg/m2) less than the 85th percentile for age and gender; we classified adolescents with a BMI (kg/m2) greater than the 85th percentile for age and gender as overweight.11,12

Smoking, weight loss attempts and nutritional assessment

Adolescents were asked about frequency of smoking and number of cigarettes smoked per day. In addition, adolescents were also asked whether they had tried to lose weight within the last 12 months. Nutritional intake was assessed using a food frequency questionnaire and 24 h diet recall. The food frequency questionnaire included an assessment of alcohol intake. Previous studies have demonstrated the validity and reliability of reported adolescent alcohol intake.10,11,12 Intake of fat and energy were calculated using the USDA's Survey Nutrient Data Base (SNDB) based on the 24 h dietary recall, which the adolescents provided themselves. Interviews were conducted privately, by trained study staff, and staff performance was monitored routinely.

Laboratory testing

Serum cotinine levels were measured using an isotope dilution, liquid chromatography, tandem mass spectrometry method. Cotinine, a long-lasting metabolite of nicotine (t1/2=15–20 h), is considered the most specific and sensitive biological marker of cigarette smoking.13 Serum cotinine cut-off levels of 15 ng/ml were used to designate smokers and non-smokers. Previous studies using the NHANES III data have demonstrated a 96% concordance between self-reported smoking status and serum cotinine levels above or below 15 ng/ml.14

Statistics

For the purposes of this study, ‘adolescents’ were defined as 12–18-y-old children and ‘smokers’ were defined as those adolescents with a serum cotinine level of 15 ng/ml or higher. Since the NHANES III study oversampled black people, Hispanic people, and younger adolescents, the data were adjusted to account for unequal selection by using sample weights provided by NHANES III. Differences in proportions were assessed using chi-square. Odds ratios were calculated using logistic regression. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was utilized to assess the independent effects of smoking on nutritional intake after adjusting for age, gender and family income. In order to adjust for complex sample design and clustering effects in the NHANES III sample, statistical significance was assessed using the balanced repeated replication method using the software package WesVarPC (Westat Inc., Rockville, MD).

Results

Overall concordance between self-reported smoking status and serum cotinine levels was 92.7% (Table 1). In particular, 96.5% of adolescents with cotinine levels below 15 ng/ml were self-reported non-smokers while 69.6% of adolescents with serum cotinine levels above 15 ng/ml were self-reported smokers. As a result, sensitivity for self-report was 77% and specificity was 95%. For both boys and girls, prevalence of both self-reported smoking and elevated serum cotinine levels were significantly more common in older adolescents compared to younger adolescents (P<0.001). There was no difference in family income between smokers and non- smokers (P=0.95).

Similar levels of smoking were present in normal-weight and overweight girls (17.0% vs 15.2%, P=0.51). However, normal-weight girls who reported trying to lose weight were over twice as likely to smoke as normal-weight girls who did not try to lose weight (23.7% vs 12.6%, P<0.01; odds ratio: 2.16 (1.26–3.72)). In addition, normal-weight female smokers who attempted to lose weight reported smoking almost twice as many cigarettes per day as normal-weight female smokers who did not try to lose weight (cigarettes/day: 14.1±1.1 vs 8.6±1.2, P<0.001). In contrast, there was no difference in smoking among overweight girls who tried to lose weight and those who did not (15.8% vs 14.1%, P=0.76).

Similar results were observed in boys. Prevalence of smoking was similar in normal-weight and overweight boys (22.2% vs 19.4%, P=0.44). There was a trend for normal-weight boys attempting weight loss to smoke more often than normal-weight boys who did not attempt to lose weight (35.5% vs 21.6%, P=0.11; odds ratio 2.00 (0.86–4.61)). However, among overweight boys, those who were trying to lose weight were significantly less likely to smoke compared to those who were not trying to lose weight (9.8% vs 24.5%, P<0.05).

Too few smoking adolescents were enrolled to determine whether racial differences existed in patterns of smoking and attempted weight loss. In addition, too few younger adolescents were smokers to determine whether smoking and attempted weight loss was related to age.

After adjusting for age and gender, there were no differences in reported caloric intake (P=0.75) and total fat intake (P=0.13) between adolescent smokers and non-smokers (Table 2). After adjusting for age, there was also no difference in BMI between smokers and non-smokers among either normal weight boys (P=0.26), overweight boys (P=0.84), normal-weight girls (P=0.36), or overweight girls (P=0.98). However, smokers reported significantly lower fruit and vegetable intake per day (Table 2). Adolescents who smoked had substantially lower levels of serum vitamin C and β-carotene compared to non-smokers (vitamin C, 35.9±2.9 vs 47.4±1.6, P<0.001; β-carotene, 0.19±0.01 vs 0.26±0.01, P<0.001). In addition, alcohol intake was significantly higher among smokers in both the 24 h dietary recall (P<0.001) and the food frequency record (P<0.001). In fact, adolescent smokers were over five times more likely to report alcohol consumption compared to adolescent non-smokers (odds ratio: ≥1×/month, 5.28 (3.82–7.28); ≥4×/month, 5.29 (3.58–7.82)).

Discussion

This study demonstrates over a two-fold increase in smoking among normal-weight adolescent girls who have tried to lose weight in a large, cross-sectional national cohort. By using objective measures of smoking status, this study has confirmed previous findings showing a similarly increased risk of smoking among girls who report either excessive weight concerns or frequent dieting.1,2,3 In contrast, there was no increased risk of smoking among either overweight girls or overweight boys trying to lose weight. In fact, overweight boys who were trying to lose weight were significantly less likely to smoke than those who were not trying to lose weight. These results imply that normal-weight girls may adopt more pathological methods of weight loss than overweight girls and boys.

Overall dietary intake was worse in adolescents who smoked compared to those who did not. While there were no detectable differences in reported caloric or fat intake among adolescent smokers and non-smokers, smokers ate significantly less fresh fruit and vegetables. Similar findings have been previously reported by Coulson and colleagues.15 Studies in adults also report less healthy diets in smokers compared to non-smokers. A meta-analysis of over 60 studies in adults examining patterns of nutrient intake in smokers revealed a slight increase in total calories and fat among smokers as well as decreased intake of fiber, fruit and vegetables.16 Adolescent smokers were also more than five times more likely to consume alcohol on a regular basis than non-smokers. In addition, Crisp and colleagues have demonstrated more than a seven-fold increase in alcohol consumption among adolescents who smoke.17 Therefore, this study confirms the clustering of adolescent smoking with adverse health and dietary behaviors which has been previously described.18,19

Previous studies have demonstrated that almost 40% of adolescents believe that smoking can help control their weight.20,21 Although the cross-sectional design of the study precludes any definitive conclusions on the relationship between smoking and weight loss, the finding of similar BMI as well as caloric and fat intake in both smokers and non-smokers argues against any major relationship between smoking and appetite suppression. Although there is ample evidence that smoking cessation in adults typically leads to 3–5 kg weight gain, there is no evidence that smoking initiation leads to weight loss.22 Both the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) and the Nurses Health Study demonstrate similar degrees of weight gain over a 7–8 y period in those who initiated smoking and those who never smoked.23,24 Unfortunately, the NHANES III data does not include objective measures of physical activity or energy expenditure which could be influenced by nicotine or other cigarette byproducts.25

The causal mechanism for the association between smoking and dieting among adolescents remains speculative. While it is likely that many adolescents begin smoking in order to lose weight, it is also possible that dieting leads to increased rates of smoking and alcohol use. Krahn and colleagues have hypothesized that the feelings of deprivation associated with dieting may increase the desire for both cigarettes and alcohol.26 In animal models, food deprivation is one of the most powerful stimulants for increased self-administration drugs, alcohol and nicotine.27 In young women, Jones et al,28 Hatsukami et al29 and Beary et al30 have shown that the prevalence of daily alcohol use increases dramatically after the onset of bulimia.

In this study, serum cotinine levels were used as an objective measure of smoking. While previous studies have generally confirmed the reliability of self-reported smoking, many adolescent smokers underestimate the amount of cigarettes they smoke or even deny smoking.6 Murray and colleagues have demonstrated that adolescent disclosure of cigarette smoking is also different when adolescents are promised confidentiality but not anonymity compared to when the adolescents are promised both confidentiality and anonymity.6 In this study, the results were both confidential and anonymous. Nevertheless, the sensitivity and specificity of self-reported smoking among adolescents was 77% and 95%, respectively, which is comparable to results obtained by other authors using similar methodology.31,32,33

In summary, the use of the NHANES III data and its inclusion of serum cotinine levels provides the most objective measure of the relationship between smoking and attempted weight loss in adolescence. Normal-weight adolescent girls who are trying to lose weight are particularly likely to smoke. In addition, these results also highlight the clustering of high-risk health patterns among adolescents—smoking, dieting, alcohol consumption, and poor fruit and vegetable intake. Although many adolescents believe that smoking will decrease their weight, this study demonstrates similar BMI, caloric intake and fat intake among smokers.

Notes

Serum cotinine levels were not measured in the second phase of NHANES III (1992–1994).

References

Ryan Y, Gibney MJ, Flynn MAT . The pursuit of thinness: a study of Dublin schoolgirls aged 15 y Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1998 22: 485–487.

Tomeo CA, Field AI, Berkey CS, Colditz GA, Frazier LA . Weight concerns, weight control behaviors, and smoking initiation Pediatrics 1999 104: 918–924.

French SA, Perry CL, Leon GR, Fulkerson JA . Weight concerns, dieting behavior, and smoking initiation among adolescents. A prospective study Am J Public Health 1994 84: 1818–1820.

Barlow SE, Dietz WH . Obesity evaluation and treatment: expert committee recommendations Pediatrics 1998 102: e29.

Severson HH, Ary DV . Sampling bias due to consent procedures with adolescents Addict Behav 1983 8: 433–437.

Murray DM, Perru CL . The measurement of substance use among adolescents: when is the ‘bogus pipeline’ method needed Addict Behav 1987 12: 225–233.

Plan and operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–94. National Center for Health Statistics Vital Health Stat 1994 1: 32.

Must A, Dallal GE, Dietz WH . Reference data for obesity: 85th and 95th percentiles of body mass index (wt/ht2) and triceps skinfold thickness Am J Clin Nutr 1991 53: 839–846 [Errata, Am J Clin Nutr 1991; 54: 773.]

Himes JH, Dietz WH . Guidelines for overweight in adolescent preventive services: recommendations from an expert committee Am J Clin Nutr 1994 59: 307–316.

Biemer PP, Witt M . Repeated measures estimation of measurement bias for self-reported drug use with applications to the National Household Survey of Drug Abuse In: The validity of self-reported drug use: improving the accuracy of survey estimates National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Mongograph 167. NIH Publication no. 97-4147. NIH 1997 439–476.

Brenen ND, Collins HL, Kann L, Warren CW, Williams BI . Reliability of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey Questionnaire Am J Epidemiol 1995 141: 575–580.

Campanelli PC, Dielman TE, Shope JT . Validity of adolescents' self-reports of alcohol use and misuse using a bogus pipeline procedure Adolescence 1987 22: 7–22.

Benowitz NL . Biomarkers of environmental tobacco smoke exposure Environ Health Persp 1999 107: (Suppl 2): 349–355.

Caraballo RS, Giovino GA, Pechacek TF, Mowery PD, Richter PA, Strauss WJ, Sharp DJ, Eriksen MP, Pirkle JL, Maurer KR . Racial and ethnic differences in serum cotinine levels of cigarette smokers: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–91 JAMA 1998 280: 135–139.

Coulson NS, Eiser C, Eiser JR . Diet, smoking and exercise: interrelationships between adolescent health behaviors Child Care Health Devl 1997 23: 207–216.

Dallongeville J, Marecaux N, Fruchard JC, Amouye P . Cigarette smoking is associated with unhealthy patterns of nutrient intake: a meta-analysis J Nutr 1998 128: 1450–1457.

Crisp AH, Statvrakaki C, Halek C, Williams E, Sedgwick P, Kiosissis I . Smoking and pursuit of thinness in schoolgirls in London and Ottawa Postgrad Med J 1998 74: 473–479.

Burke V, Milligan RAK, Beilin LJ, Dunbar D, Spencer M, Balde E, Gracey MP . Clustering of health-related behaviors among 18-year old Australians Prev Med 1997 26: 724–733.

Pate RR, Health GW, Dowda M, Trost SG . Associations between physical activity and other health behaviors in a representative sample of US adolescents Am J Public Health 1996 86: 1577–1581.

Klesges RC, Elliot VE, Robinson LA . Chronic dieting and the belief that smoking controls body weight in a biracial, population-based adolescent sample Tobacco Control 1997 6: 89–94.

Camp DI, Klesges RC, Relyea G . The relationship between body weight concerns and adolescent smoking Health Psychol 1993 12: 24–32.

Klesges RC, Zbikowski SM, Lando HA, Haddock CK, Talcott GW, Robinson LA . The relationship between smoking and body weight in a population of young military personnel Health Psychol 1998 17: 454–458.

Klesges RC, Ward KD, Ray JW, Cutter G, Jacobs DR, Wagenknecht LE . The prospective relationships between smoking and weight in a young, biracial cohort: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study J Consult Clin Psychol 1998 66: 987–993.

Coditz JA, Segal MR, Myers AH, Stampfer MJ, Willet W, Speizer FE . Weight change in relation to smoking cessation among women J Smoking Relat Disord 1992 3: 145–153.

Collins LC, Walker J, Stamford BA . Smoking multiple high- versus low-nicotine cigarettes: impact on resting energy expenditure Metabolism Clin Exp 1996 45: 923–926.

Krahn D, Kurth C, Demitrack M, Drewnoswki A . The relationship of dieting severity and bulimic behaviors to alcohol and other drug use in young women J Subst Abuse 1992 4: 341–353.

Krahn DD . The relationship of eating disorders and substance abuse J Subst Abuse 1991 3: 239–253.

Jones DA, Cheshire N, Moorhouse H . Anorexia nervosa, bulimia and alcoholism—association of eating disorder and alcohol J Psychol Res 1985 19: 377–380.

Hatsukami D, Mitchell JE, Eckert ED, Pyle R . Characteristic of patients with bulimia only, bulimia with affective disorder, and bulimia with substance abuse problems Addict Behav 1986 11: 399–406.

Beary MD, Lacey JH, Merry J . Alcoholism and eating disorders in women of fertile age Br J Addic 1986 81: 685–689.

Bauman KE, Ennett SE . Tobacco use by black and white adolescents: the validity of self-reports Am J Public Health 1994 84: 394–398.

Wills TA, Cleary SD . The validity of self-reports of smoking: analysis by race/ethnicity in a school sample of urban adolescents Am J Public Health 1997 86: 56–61.

Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thoimpson DC, Diehr P, Koepsell T, Kinne S . The validity of self-reported smoking: a review and meta-analysis Am J Pub Health 1994 84: 1086–1093.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Strauss, R., Mir, H. Smoking and weight loss attempts in overweight and normal-weight adolescents. Int J Obes 25, 1381–1385 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801683

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801683

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Orthorexia nervosa and substance use for the purposes of weight control, conformity, and emotional coping

Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity (2022)

-

Smoking as a weight control strategy of Serbian adolescents

International Journal of Public Health (2020)

-

Childhood psychosocial challenges and risk for obesity in U.S. men and women

Translational Psychiatry (2019)

-

Kardiovaskuläre Risikofaktoren im Kindes- und Jugendalter

Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz (2013)

-

Factors Affecting Tobacco Use Among Middle School Students in Saudi Arabia

Maternal and Child Health Journal (2012)