Abstract

Study Design:

Retrospective, case series.

Design:

A review of 10 surgical cases with symptoms of cervical angina.

Objective:

To stress the importance of symptoms of cervical angina in patients with cervical spine disorders.

Setting:

Fukui University Hospital, Japan.

Results:

A total of 10 patients complaining of symptoms of cervical angina were admitted with a tentative diagnosis of coronary artery disease. Pain relief was achieved by anterior surgical decompression in all patients.

Conclusion:

We stress that physicians should be aware of the symptoms of cervical angina and that surgical intervention often leads to complete relief of symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical spine disorders may often be present with pain in the upper anterior chest and scapular areas, resembling true angina pectoris.1, 2, 3 Anterior chest pain associated with cervical intervertebral disc diseases, ossified posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL), or other spinal disorders, has been sometimes described as ‘cervical angina’3, 4 and appears to be relatively unknown clinical syndrome. Prompt and accurate diagnosis requires a strong sense of suspicion in patients with inadequately explained chest pain. Jacobs5 suggested that C6 and C7 nerve roots are the most frequently involved and the pain is possibly mediated via the medial and lateral pectoral nerves. Spine specialists should be well aware of this presentation in their routine clinical examinations but, unfortunately and in fact, a number of patients still appear to be diagnosed as coronary artery disease, and thus undergo unnecessary examinations and medications.

In the present short communication, we describe 10 surgical cases in whom cervical spine disorders were misdiagnosed over long periods. We emphasize the importance of these clinical symptoms in the diagnosis of cervical spine disorders.

Patients and methods

Between 1991 and 2004, a total of 706 patients underwent cervical spine surgeries because of neurological symptoms and signs, such as myelopathy (n=314), myeloradiculopathy (n=162), radiculopathy (n=198), or so-called ‘discopathy’ (n=32). Reviewing the clinical charts in retrospect, 10 patients had presented with cervical angina as the main symptom. Of these, three patients visited our hospital directly when the neck and anterior chest pain symptoms appeared, but the clinical presentations of the other seven cases were considered different and included true angina pectoris and neurosis. These 10 cases were retrospectively reviewed with respect to the clinical features, radiological findings, and the results of other specific tests.

Radiographic examination included flexion-extension lateral films and, in some cases, discography. In our Neuro-orthopaedic Unit, myelography was excluded from routine radiological examination since 1996 due to its biological invasiveness. Radiological examination included the following workup as we reported previously.6, 7 (i) Lordotic alignment of the cervical spine on radiographs taken in neutral positions, designated as cervical spine lordosis. (ii) Reduction of bony spinal canal size, measured on lateral films, at suspected vertebral level responsible for neural compression. (iii) Lordotic alignment of the cervical spinal cord on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; 1.5 Tesla Signa, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA), termed spinal cord lordosis. Other radiographic abnormalities were intervertebral disc space narrowing, spondylotic osteophyte formation, and the existence of OPLL. In addition, MR angiography was conducted in three patients who suffered from other symptoms, such as vertebral insufficiency syndrome.

All surgeries were performed by one of the authors (H Baba) using a uniform surgical technique as described previously.6, 7, 8, 9 A left-side anterolateral oblique incision was pursued for the anterior cervical spine followed by Robinson's anterior decompression and interbody fusion or subtotal spondylectomy with autologous iliac bone grafting. In OPLL, the essential technique was resection of the ossified plaque anteriorly with complete decompression of the spinal cord.9 Neurological assessment after surgery was performed by independent observers other than the principal surgeon.

A written informed consent was obtained from all patients and the study strictly followed the Guidelines of the Ethical Committee of Fukui University.

Results

Clinical presentation before and after surgical treatment

Table 1 shows the preoperative and postoperative clinical demographic data of the 10 patients (six men and four women). The average age of these patients was 54.5 years (range: 36–74 years). The average duration of symptoms prior to definitive diagnosis was 5.6 months (range: 2–12 months). The background disease was cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM, n=3), cervical disc herniation (CDH, n=6), and OPLL (n=1). The affected levels were C4–5 level in three cases, C5–6 level in four cases, and C6–7 level in three cases. All patients improved after anterior decompressive surgeries.

We classified the chest pain based on its localization. Five cases had retrosternal pain, three cases had left lower anterior chest pain, and two cases had epigastric pain. Five cases had autonomic symptoms (eg, difficulty of breathing, vertigo, and headache). Upper arm neurological symptoms and left lower anterior chest pain tended to appear simultaneously in patients with radiculopathy, and autonomic symptoms tended to appear conspicuously rather than upper arm symptoms in the myelopathy cases.

Illustrative case presentation

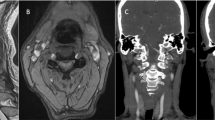

Case 6: A 54-year-old woman was admitted to our University Hospital with complaints of left upper arm pain and left lower anterior chest pain especially when putting her right arm down. She had undergone angiography at other hospitals for suspected cardiovascular disease or thoracic outlet syndrome. The duration of symptoms prior to definitive diagnosis was 3 months. MRI findings were presence of cervical disc herniation at right-sided C5–6 level (Figure 1). A diagnosis of cervical angina was made, and she underwent anterior decompression followed by interbody fusion (Robinson’s procedure) at C5–6 level. Pain-related symptoms including chest pain improved immediately after surgery.

Case 7: A 36-year-old man was admitted to our University Hospital with complaints of left upper arm pain and difficulty of breathing, vertigo, and headache. Neurological examination revealed a brisk deep tendon reflex of upper and lower limbs. He had consulted a cardiovascular physician and a neurosurgeon, and 12 months elapsed before making a definitive diagnosis. X-ray findings included presence of segmental OPLL at C5 and C6. MRI findings included presence of segmental OPLL and cervical disc herniation on left-side of C6–7 (Figure 2). Diagnosis of cervical angina was made, and he underwent anterior decompression with interbody fusion at C5–7 level (C6 subtotal spondylectomy). The autonomic symptoms improved immediately after surgery while the other myelopathy symptoms improved gradually.

Discussion

Among the multitude of symptoms of cervical spine disorders, cervical angina may be miscellaneous, but it must be always recognized in clinical practice.4, 10, 11, 12 In addition, the symptoms tend to be misidentified more frequently in elderly individuals because of increased incidence of coronary artery diseases. The symptom is rather easily recognizable when the patient presents with neurological signs of spinal cord compromise, however, actually frequently, it appears to be a missing problem without careful examination. Many investigators1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 11, 12 have described details of this status but it appears still neglected in the routine clinical practice.

Oille13 was perhaps the first to describe the symptom in 1937 patients with chest pain of cervical nerve root origin. Jacobs5 also reported a large series of 164 cases with cervical angina observed over 20 years. Brodsky14 reported the largest series of 438 cases with cervical angina, and perhaps had made the finest insight into the physiological etiologies. On the other hand, Iwasa15 found only three (5%) of 63 patients with angina pectoris had cervical nerve root compression, and LaBan et al12 also described a low incidence of true cervical angina. Why there is a wide spectrum of incidence of cervical angina? The frequency may be a continuing quest mainly because of differences in patient sampling, diagnostic criteria, and more importantly, variability of symptoms. Reviewing 706 patients who underwent cervical spine surgeries between 1991 and 2004, we found approximately 1.4% of those were considered to have exhibited symptoms of cervical angina. However, we presume the true frequency to be actually higher because there were cases examiners or patients did not recognize these symptoms as cervical spine disorders.

There is a debate on the physiological etiology of cervical angina syndrome. Brodsky15 indicated that radicular pain is the direct cause, and LaBan et al12 presumed that the spinal cord ventral roots produced protopathic pain around the chest. González-Darder et al16 considered deactivation of the descending inhibitory system as the main cause of symptoms. Other possible factors may be sympathetic pain and sino-vertebral pain.

Although coronary arteriography has advanced the diagnosis of angina pectoris and distinction between chest pain of coronary origin as opposed to that arising from other structures, unnecessary invasive procedures should be avoided, if possible. Prompt and accurate diagnosis requires a strong sense of suspicion in patients with inadequately explained chest pain. According to the Jacobs's observation,5 common manifestations associated with cervical angina include neck and arm pain, upper arm radicular symptoms and fatigue, parasternal tenderness, and occipital headache. Brodsky14 stressed the presence of associated autonomic or other symptoms such as dyspnea, nausea, diaphoresis, diplopia, and sympathetic nervous signs. These complex symptoms appear well known when the patients have compression of the cervical spinal cord and/or cervical nerve root. Constant1 indicated that chest pain is likely nonanginal if its duration is >30 min or <5 s, increases with inspiration, can be induced by a single movement of the trunk or arm, by local fingers pressure or bending forward, or if it disappears immediately on lying down. There are also many presumptive signs of nonanginal chest pain such as localization with one finger, radiation to the nuchal area, an inflammatory primary site, pain that reaches maximum at onset, or relief within a few seconds of swallowing food. Neurological sign and oesophageal spasm are features that help rule out angina. However, the possibility of coexistent organic coronary disease and cervical angina must be kept in mind.

In our cases, left lower chest pain tended to appear as a radicular sign, retrosternal, epigastric pain, and autonomic symptoms tended to be accompany myelopathy. In the myelopathy cases, autonomic symptoms were more evident than upper arm symptoms. Therefore, cervical angina may be more difficult to diagnose and there is a need for great care especially in myelopathy cases.

Routine MRI examination, or even if myelopathy is suspected, is insufficiently informative for the functional assessment of cervical angina. Perhaps, discography and/or selective nerve root infiltration with xylocaine block may be the best tool to make a functional diagnosis of cervical angina syndrome associated with spinal cord and/or nerve root compression. However, these invasive tests should be considered carefully. On the other hand, F-2-fluoro-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography may be useful for detection of neural dysfunction of the spinal cord17 affecting the somatic as well as autonomic nervous disorders around the chest. Rest and neck collar fixation or nitro-glycerine medication may be recommended as an alternative approach to establish the diagnosis. It is obvious that defective coronary artery circulation is an extremely serious problem. Once coronary artery disease has been adequately excluded, the possibility of a cervical angina syndrome should be considered, especially if accompanied by signs of cervical radiculopathy or myelopathy. When it is difficult to distinguish between true angina pectoris and cervical angina, adequate coronary diagnostic studies are imperative.

A careful approach should be followed when treating cervical angina syndrome. Several groups3, 5, 14 have observed spontaneous resolution of the symptoms or that a simple external neck fixation helps in pain elimination, either transiently or permanently. Approximately three quarters of the patients had been estimated to improve with conservative treatment.14 However, in cases where neurological compromise is evident by spinal cord and/or nerve root compression, surgery may be necessary to produce rapid improvement. Patients with cervical angina suffer from discomfort and uneasy chest pain. When these symptoms continue and the patient does not show response to conservative therapy, one must consider surgery, since, at least occasionally, an aimless conservative therapy is not good. We believe that unnecessary or doubtful surgical intervention must be strictly avoided. However, based on our experience even in a small series, anterior cervical surgery to correct nerve root or spinal cord compression can be a useful option for pain relief. On the other hand, regarding cardiac examination, physicians must always be aware of this miscellaneous syndrome in order to avoid unnecessary coronary artery examination. In this point of view, appropriate and cooperative approach in physical examination must be followed among the specialists.

References

Constant J . The diagnosis of nonanginal chest pain. Keio J Med 1990; 39: 187–192.

Forrester JS, Herman MV, Gorlin R . Noncoronary factors in the angina syndrome. N Engl J Med 1970; 283: 786–789.

Guler N et al. Acute ECG changes and chest pain induced by neck motion in patients with cervical hernia: a case report. Angiology 2000; 51: 861–865.

Wells P . Cervical angina. Am Fam Physician 1997; 55: 2262–2264.

Jacobs B . Cervical angina. NY State J Med 1990; 90: 8–11.

Baba H et al. Late radiographic findings after anterior cervical fusion for spondylotic myeloradiculopathy. Spine 1993; 18: 2167–2173.

Baba H et al. Lordotic alignment and posterior migration of the spinal cord following en bloc open-door laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy: a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurol 1996; 243: 626–632.

Baba H et al. Anterior decompressive surgery for ossified posterior longitudinal ligament causing myeloradiculopathy. Paraplegia 1995; 33: 18–24.

Baba H et al. Laminoplasty with foraminotomy for coexisting cervical myelopathy and unilateral radiculopathy: a preliminary report. Spine 1996; 21: 196–202.

Cheshire Jr WP . Spinal cord infarction mimicking angina pectoris. Mayo Clin Proc 2000; 75: 1197–1199.

Gadour M, Rajbhandari SM, Tesfaye S . Cervical spine infection presenting as angina. Hosp Med 1999; 60: 217–218.

LaBan MM, Meerschaert JR, Taylor RS . Breast pain: a symptom of cervical radiculopathy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1979; 60: 315–317.

Oille JA . Different diagnosis of pain in the chest. Can Med Assoc J 1937; 37: 209–216.

Brodsky AE . Cervical angina. A correlative study with emphasis on the use of coronary arteriography. Spine 1985; 10: 699–709.

Iwasa M . Clinical analysis of angina pectoris and angina-like pain: with special reference to ECG during attack, ‘cervical spondylosis’ and selective coronary arteriography. Jpn Circ J 1976; 40: 1191–1203.

González-Darder JM, González-Martínez V, Canela-Moya P . Cervical spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of severe angina pectoris. Neurosurg Quart 1998; 8: 16–23.

Uchida K et al. Metabolic neuroimaging of the cervical spinal cord in patients with compressive myelopathy: a high-resolution positron emission tomography study. J Neurosurg (Spine 1) 2004; 1: 72–79.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a grant (2003) from the Investigation Committee on Ossification of the Spinal Ligaments, the Public Health Bureau of the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nakajima, H., Uchida, K., Kobayashi, S. et al. Cervical angina: a seemingly still neglected symptom of cervical spine disorder?. Spinal Cord 44, 509–513 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101888

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101888