Abstract

Traditionally, the efficacy of an anticancer agent has been measured by response rate. With the development of biological molecular-targeted agents, which have a different mechanism of action from conventional agents, it may be appropriate to consider alternative criteria that reflect the positive effect of these biological agents on disease control, palliation, symptom improvement and quality of life. One such targeted agent is the orally active epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib (‘Iressa’, ZD1839). This article reviews the clinical experience of patients with advanced/metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer, who have received gefitinib as part of a clinical trial or through the ‘Iressa’ Expanded Access Programme. Disease-control rates of ∼50% were observed in some Expanded Access Programme series, comparable with results obtained from Phase II trials. Symptom improvement was also reported. Information that will help identify those patients most likely to respond to treatment will become increasingly important. Therefore, the possible role of prognostic markers and the relationship between epidermal growth factor receptor status and response to gefitinib has been investigated. No clear association between epidermal growth factor receptor expression and response was observed. Future studies of other biomarkers in the epidermal growth factor receptor pathway should help to identify which patients are likely to benefit most from gefitinib.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Patients with advanced/metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have terminal disease. Therefore, treatment should aim to improve palliation, quality of life and symptom improvement in addition to prolonging survival. The benefits of biologically targeted agents like gefitinib (‘Iressa’, ZD1839) are not always evident from response rates, as their mechanism of action differs from that of conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy agents. Assessments of efficacy should take into account the overall benefit to the patient, including disease control and effects on quality of life and symptoms. In addition to efficacy data from clinical trials, data are now available from the ‘Iressa’ Expanded Access Programme (EAP). Some of these data are reviewed below.

Currently, there is much interest in the role of prognostic/predictive factors and, in the future, these will become increasingly important in targeting therapy to those patients who are most likely to benefit. A range of baseline demographic factors and potential predictive biological markers are under investigation in patients receiving gefitinib, the significance of which remains to be clarified.

Clinical benefit with gefitinib

Unprecedented activity in NSCLC patients who have been pretreated was demonstrated in Phase II gefitinib monotherapy studies (‘Iressa’ Dose Evaluation in Advanced Lung cancer) (IDEAL 1 and 2) (Fukuoka et al, 2003; Kris et al, 2003). Response rates with gefitinib 250 mg day−1 were 18.4 and 11.8% in IDEAL 1 and 2, respectively. However, when disease control was considered (objective response plus stable disease), it was evident that 54.4 and 42.2% of patients in IDEAL 1 and 2, respectively, experienced clinical benefit. Furthermore, ∼40% of patients in each trial experienced improvement in disease-related symptoms, assessed using the Lung Cancer Subscale (LCS) of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) questionnaire (improvement rates at 250 mg day−1 were 40.3 and 43.1%, respectively), which was associated with a longer overall survival compared with patients without improvement (Douillard et al, 2002; Natale et al, 2002; Cella et al, 2003). These results emphasise that, for a targeted agent like gefitinib, valuable clinical benefit can be experienced by the patient that might not be reflected by the response rate.

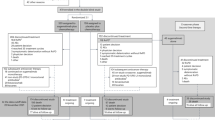

Similar results have been observed in the compassionate-use setting, an example of which was presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting 2003 (López Martin et al, 2003), with updated results presented at the recent ‘Iressa’ Clinical Experience (ICE) meeting (Cortes-Funes, ICE abs). Patients were included in the ‘Iressa’ EAP if they had experienced progression of NSCLC after prior chemotherapy, were ineligible for other gefitinib studies and had no alternative treatment options. In this study, patients received treatment with oral gefitinib 250 mg day−1 for at least 1 month, which was the minimum time to evaluate efficacy. In addition to response rate, disease control rate (defined as objective response plus stable disease) and clinical benefit (defined in this analysis as an improvement in two principal variables, such as pain or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, or symptomatic improvement, such as cough or haemoptysis, plus improvement in one secondary variable, such as weight) were also recorded. Data from 26 centres throughout Spain were analysed retrospectively. The four major centres were Clinica Universitaria Navarra, Hospital de Pontevedra, Hospital GTP Badalona and Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre.

Demographic characteristics of the 113 patients from this Spanish series who fulfilled EAP criteria are given in Table 1. In total, 96 patients were evaluable for response, with the remaining 17 patients being evaluable only for clinical benefit. Seven patients (7.3%) had a partial response, examples of which are shown in Figures 1A and B. Disease control was experienced by 44 (45.8%) patients and disease control rates were similar, regardless of histology, stage at diagnosis or previous chemotherapy. Additionally, 23 out of 113 patients (20.4%) experienced symptom benefit (evaluated retrospectively from patient charts). Clinical benefit, as defined above, was observed in 59.2% of patients. Median time to disease progression and median overall survival were 3.5 and 6.7 months, respectively (Figures 2A and B).

Drug-related adverse events recorded in this study were mainly grade 1/2 (Table 2). There were four withdrawals, due to drug-related adverse events (diarrhoea and fatigue in progressive disease). It can be concluded from the Spanish experience that gefitinib was well tolerated and showed antitumour activity in these pretreated patients with advanced NSCLC, with a promising rate of disease control and clinical benefit.

Efficacy data from the IDEAL trials were further supported by 20 large case series from the EAP (each with >25 patients) that were presented at the ICE meeting (Mancuso, ICE abs; Haringhuizen, ICE abs; Bendel, ICE abs; Gridelli (a and b), ICE abs; Bianco, ICE abs; de Leeuw, ICE abs; Petersen, ICE abs; Reck, ICE abs; Soto Parra (a–c), ICE abs; Cortes-Funes, ICE abs; Kowalczyk, ICE abs; Chioni, ICE abs; Katz, ICE abs; Pallis, ICE abs; de Braud, ICE abs; Razis, ICE abs; Boyer, ICE abs). Patients from these case series were commonly heavily pretreated (Figure 3). For most case series, response rates were <10%. In contrast, disease control was experienced by many patients, with disease control rates of 5.7–83% reported across the series (Figure 4). Some series described evidence of symptom improvement. In all, 11 of the large case series presented data on median survival (Figure 5), which ranged from 3–7 months. The study with median survival of 7 months also reported a 1-year survival of 31% (Kowalczyk, ICE abs).

There were several presentations at the 10th World Conference on Lung Cancer (WCLC) that reported data from the compassionate-use setting (Gips et al, 2003; Haringhuizen et al, 2003; Janne et al, 2003; Park et al, 2003; Soto Parra et al, 2003). Response rates with gefitinib were varied, but most reports described disease control rates of >40%, comparable with data from the Phase II IDEAL trials. Furthermore, 1-year survival rates of 29% (Haringhuizen et al, 2003; Janne et al, 2003) and 48.7% (Park et al, 2003) were reported.

Relationship between disease control and survival/symptom improvement

In IDEAL 2, median overall survival in the subset of patients surviving for >8 weeks was greater for patients with partial response (16.3 months) or stable disease (9.4 months) than for those with progressive disease (5.4 months) (Cella et al, 2003). A similar association was noted in two of the large case series from the ICE meeting that evaluated survival by disease control (Soto Parra (a and b), ICE abs). In the first, median survival was longer for patients with disease control (6 months) compared to that for all patients (4 months). In the second, median survival was 5 months for those with stable disease compared to 2.5 months for patients with progressive disease, and was 3 months overall. This study also reported a corresponding difference in 1-year survival (28% for those with stable disease vs 22% overall).

A correlation between symptom improvement and tumour response was observed for IDEAL 2, such that most patients with a tumour response or stable disease had symptom improvement (Cella et al, 2003). Four of the large case series at the ICE meeting had information on symptom-improvement rates, which ranged from 19–39% (Haringhuizen, ICE abs; Petersen, ICE abs; Kowalczyk, ICE abs; Pallis, ICE abs). In addition to an overall symptom improvement rate of 39%, Pallis et al noted that 83% of patients with disease control had symptom improvement.

Prognostic markers and epidermal growth factor receptor status

The identification of prognostic and predictive factors is important because it should help to determine which patients will benefit most from therapy. There are a number of biological markers involved in cell signalling pathways, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), p27 and Ki67, that might have potential as prognostic/predictive markers (Fu et al, 1999; Arteaga, 2002). Although EGFR is commonly expressed in NSCLC and other tumours, its role as a prognostic factor is not well defined and conflicting results have been reported (Nicholson et al, 2001). This may, in part, be due to the lack of a standard validated method for assessing EGFR expression, which makes it difficult to compare results from different studies (Arteaga, 2002). It is not known whether the level of EGFR expression is predictive of response to EGFR-targeted therapy. Recent data on the relationship between EGFR expression levels and the response to gefitinib are now available from the Phase II IDEAL trials and the EAP.

An exploratory analysis of EGFR expression in tumour biopsies has recently been performed by immunohistochemistry in the IDEAL 1 and 2 trials, in which formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections were stained with the 2-18C9 clone antibody. Four levels of staining intensity were recorded: none (0), weak (1+), moderate (2+) or strong (3+). This method of visual scoring of immunohistochemical stains for EGFR by experienced observers, using a simple and objective scoring system, was shown to be highly reproducible (Janas et al, 2003). Patients evaluable for EGFR status plus either objective response or symptom improvement were assessed. There was no evidence for a consistent relationship between EGFR expression levels and response (Bailey et al, 2003). Patients with low and high levels of EGFR responded to gefitinib. There was a tendency towards a positive correlation between symptom improvement and strong (3+) EGFR membrane staining, but some patients with symptom improvement had samples without strong staining. Therefore, it would be clinically unacceptable to select patients for gefitinib treatment on the basis of strong EGFR staining.

An Italian case series from the EAP aimed to evaluate the role of EGFR detection on prediction of response or disease control in patients treated with gefitinib. Results from 50 evaluable patients were presented recently at the WCLC (Soto Parra et al, 2003), updated from data presented at the ICE meeting (Soto Parra (c), ICE abs). Consistent with the studies described above, response rate was 10% (one complete and four partial responses) and 50% of patients experienced disease control with a median duration of 6 months.

Immunohistochemistry was used to analyse EGFR membrane immunoreactivity, which was classified according to staining intensity (negative/faint (0/1+) or medium/strong (2+/3+)) (Figure 6) and percentage of immunoreactive (IR) cells (negative/low expressors (0–19% IR) or high expressors (⩾20% IR)). In this exploratory analysis, there was no significant correlation between response to gefitinib and EGFR staining intensity (P=0.1) or between disease control and EGFR staining intensity (P=0.39) (Table 3), in agreement with the results of Bailey et al (2003).

In a selection of other cases from the EAP, variable results were observed: some responders were negative for EGFR (Gridelli (b), ICE abs) and others had positive staining for EGFR in ⩾20% of cells (de Braud, ICE abs). These results again suggest the lack of a clear association between EGFR status and response to gefitinib.

The IDEAL trials also provided some information on demographic prognostic factors. In IDEAL 1, prognostic factors associated with an objective response according to multivariate analysis included performance status (0/1 vs 2), female gender and adenocarcinoma histology (vs other histologies) (Fukuoka et al, 2003).

The Phase III trials of gefitinib in combination with standard chemotherapy in previously untreated patients with NSCLC (INTACT (‘Iressa’ NSCLC Trial Assessing Combination Treatment) 1 and 2) also included analysis of possible prognostic factors (Giaccone et al, 2003; Herbst et al, 2003). Multivariate analysis showed that performance status 2, weight loss, bone/liver metastases, squamous cell, large cell or unspecified histology were all significant for worse survival in both trials, as were male gender and brain metastases in INTACT 2. Multivariate analysis of INTACT data did not show any consistent or demonstrable effects of gefitinib in combination with chemotherapy, compared with chemotherapy alone, on known prognostic factors for survival outcome.

Another possibility for response prediction currently being evaluated is the use of a high-throughput reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction assay, to determine a correlation between quantitative gene expression in the tumour and response to gefitinib monotherapy in patients with NSCLC (Natale et al, 2003). Of 192 genes profiled in 17 patients, expression of several genes (including STAT5A, STAT5B and γ-catenin) correlated with clinical response. Further studies in a larger cohort of patients are necessary to further elucidate the significance of these genes and other candidate markers of response.

Discussion

It is clear from clinical trials that patients can experience clinical benefit from gefitinib that is not necessarily reflected in the objective response rate and so other factors, such as disease control and symptom improvement, should be taken into consideration when evaluating such targeted agents. Large case series from the EAP have been presented at international congresses and at the ICE meeting, and support the idea that patients can still experience benefit despite low response rates. Some studies suggested that disease control was related to improved survival. These data indicate that gefitinib is a promising therapy for patients with advanced NSCLC, who have few treatment options.

Another important feature of targeted therapy is the potential ability to predict response to therapy. For EGFR-targeted agents such as gefitinib, it is of interest to determine any relationship between EGFR expression levels and response, with a view to being able to select for treatment those patients who are most likely to benefit. However, it appears that there is no consistent relationship between EGFR status and response to gefitinib.

There do seem to be some patterns emerging with respect to prognostic factors, with characteristics of performance status, gender and histology influencing survival, although responses were observed in all groups. In some studies, symptom improvement has been associated with improved survival (Cella et al, 2003).

Future studies of other biomarkers in the EGFR pathway should help identify which patients are likely to benefit most from gefitinib, and extensive investigations are underway to help clarify the mechanisms of action and resistance. Tissue collection will be performed across gefitinib trials and genomic/proteomic collaborative exploratory studies are ongoing.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Arteaga CL (2002) Epidermal growth factor receptor dependence in human tumors: more than just expression? Oncologist 7(Suppl 4): 31–39

Bailey LR, Kris M, Wolf M, Kay A, Averbuch S, Askaa J, Janas M, Schmidt K, Fukuoka M (2003) Tumor EGFR membrane staining is not clinically relevant for predicting response in patients receiving gefitinib (‘Iressa’, ZD1839) monotherapy for pretreated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: IDEAL 1 and 2. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 44: 1362 (abs LB-170)

Cella D, Natale RB, Lynch TJ, Lee C, Carbone D, Douillard J-Y, Kay A, Wolf M, Heyes A, Ward J (2003) Disease-related symptoms in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer as measured by the Lung Cancer Subscale of the FACT-L questionnaire: clinically meaningful improvement with gefitinib (‘Iressa’, ZD1839). Poster presented at ASCO, Chicago, IL, USA, May 31–June 3, Poster no. 2531

Douillard J-Y, Giaccone G, Horai T, Noda K, Vansteenkiste JF, Takata I, Gatzeimeir U, Fukuoka K, Macleod A, Feyereislova A, Averbuch S, Nogi Y, Heyes A, Baselga J (2002) Improvement in disease-related symptoms and quality of life in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with ZD1839 (‘Iressa’) (IDEAL 1). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 21: 298a (abs 1195)

Fu X-L, Zhu X-Z, Shi D-R, Xiu L-Z, Wang L-J, Zhao S, Qian H, Lu H-F, Xiang Y-B, Jiang G-L (1999) Study of prognostic predictors for non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 23: 143–152

Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, Tamura T, Nakagawa K, Douillard J-Y, Nishiwaki Y, Vansteenkiste J, Kudoh S, Rischin D, Eek R, Horai T, Noda K, Takata I, Smit E, Averbuch S, Macleod A, Feyereislova A, Dong R-P, Baselga J (2003) Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 21: 2237–2246

Giaccone G, Johnson D, Scagliotti GV, Manegold C, Rosell R, Rennie P, Wolf M, Averbuch S, Grous J, Fandi A (2003) Results of a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors of overall survival of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with gefitinib (ZD1839) in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy (CT) in two large phase III trials (INTACT 1 and 2). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 22: 627 (abs 2522)

Gips M, Heching Y, Levitt M, Kuten A, Shmueli E, Segal A, Peretz T (2003) The Israeli experience with gefitinib (‘Iressa’, ZD1839) as single agent treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 41(Suppl 2): S247 (abs P-613)

Haringhuizen A, Vaessen HFR, Baas P, van Zandwijk N (2003) Gefinitib (‘Iressa’, ZD1839) as a last option for patients with recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Poster presented at the 10th WCLC, Vancouver, Canada, August 10–14

Herbst R, Giaccone G, Schiller J, Miller V, Natale R, Rennie P, Ochs J, Fandi A, Grous J, Johnson D (2003) Subset analyses of INTACT results for gefitinib (‘Iressa’, ZD1839) when combined with platinum-based chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 22: 627 (abs 2523)

Janas M, Franklin WA, Schmidt K, Bailey LR (2003) Interobserver reproducibility of visually interpreted EGFR immunohistochemical staining in non-small-cell lung cancer. Poster presented at the AACR, Washington, DC, USA, July 11–14, Poster no. LB-213

Janne PA, Gurubhagavatula S, Lucca J, Ostler P, Skarin AT, Fidias P, Lynch TJ, Johnson BE (2003) Clinical benefits in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with gefitinib (“Iressa”, ZD1839) in the compassionate use program. Lung Cancer 41(Suppl 2): S71 (abs O-243)

Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS, Lynch Jr TJ, Prager D, Belini CP, Schiller JH, Kelly K, Spiridonidis H, Sandler A, Cella D, Wolf MK, Averbuch SD, Ochs JJ, Kay AC (2003) Efficacy and safety of gefitinib (Iressa, ZD1839), an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. A randomized trial. JAMA 22: 2149–2158

López Martin A, Constenla M, Martín Algarra S, Salinas P, Massuti B, Gascón P, Castellano D, López-Picazo JM, Rosell R, Cortés-Funes H (2003) Gefitinib (‘Iressa’, ZD1839) in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients after progression on chemotherapy. Poster presented at ASCO, Chicago, IL, USA, May 31–June 3, Poster no. 2695

Natale RB, Shak S, Aronson N, Averbuch S, Fox W, Luthringer D, Clark K, Baker J, Cronin M, Agus DB (2003) Quantitative gene expression in non-small cell lung cancer from paraffin-embedded tissue specimens: predicting response to gefitinib, an EGFR kinase inhibitor. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 22: 190 (abs 763)

Natale RB, Skarin AT, Maddox AM, Hammond LA, Thomas R, Gandara DR, Gerstein H, Panella TJ, Cole J, Jahanzeb M, Kash J, Hamm J, Langer CJ, Saleh M, Stella PJ, Heyes A, Helms L, Ochs J, Averbuch S, Wolf M, Kay A (2002) Improvement in symptoms and quality of life for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients receiving ZD1839 (‘Iressa’) in IDEAL 2. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 21: 292a (abs 1167)

Nicholson RI, Gee JMW, Harper ME (2001) EGFR and cancer prognosis. Eur J Cancer 37(Suppl 4): S9–S15

Park J, Park B-B, Lee S-H, Park S-H, Lee K-E, Park JO, Kim K, Im Y-H, Kang WK, Park K (2003) Gefitinib (‘Iressa’, ZD1839) monotherapy as a salvage regimen for previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Poster presented at the 10th WCLC, Vancouver, Canada, August 10–14

Soto Parra H, Cavina R, Zucali PA, Campagnoli E, Latteri F, Morenghi E, Roncalli M, Santoro A (2003) Analysis of responses to gefitinib (‘Iressa’, ZD1839) according to epidermal growth factor receptor expressed as staining intensity or percentage of immunoreactive cells. Poster presented at the 10th WCLC, Vancouver, Canada, August 10–14

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Cortes-Funes, H., Soto Parra, H. Extensive experience of disease control with gefitinib and the role of prognostic markers. Br J Cancer 89 (Suppl 2), S3–S8 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601476

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601476

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor serum (sEGFR) level may predict response in patients with EGFR positive advanced colorectal cancer treated with gefitinib?

Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology (2008)

-

Gefitinib — a novel targeted approach to treating cancer

Nature Reviews Cancer (2004)