Abstract

Background:

Hypoxia leads to the stabilisation of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) transcription factor that drives the expression of target genes including microRNAs (miRNAs). MicroRNAs are known to regulate many genes involved in tumourigenesis. The aim of this study was to identify hypoxia-regulated miRNAs (HRMs) in bladder cancer and investigate their functional significance.

Methods:

Bladder cancer cell lines were exposed to normoxic and hypoxic conditions and interrogated for the expression of 384 miRNAs by qPCR. Functional studies were carried out using siRNA-mediated gene knockdown and chromatin immunoprecipitations. Apoptosis was quantified by annexin V staining and flow cytometry.

Results:

The HRM signature for NMI bladder cancer lines includes miR-210, miR-193b, miR-145, miR-125-3p, miR-708 and miR-517a. The most hypoxia-upregulated miRNA was miR-145. The miR-145 was a direct target of HIF-1α and two hypoxia response elements were identified within the promoter region of the gene. Finally, the hypoxic upregulation of miR-145 contributed to increased apoptosis in RT4 cells.

Conclusions:

We have demonstrated the hypoxic regulation of a number of miRNAs in bladder cancer. We have shown that miR-145 is a novel, robust and direct HIF target gene that in turn leads to increased cell death in NMI bladder cancer cell lines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Bladder cancer is the most common tumour of the urinary system (Office for National Statistics, 2010). Initial tumour resection and adjuvant therapy are associated with a high 5-year survival rate for bladder cancer (75%). However, the frequency of tumour recurrence can be as high as 80%, with disease progression occurring in up to 45% of patients (van Rhijn et al, 2009). Treatment and the necessity for regular surveillance contribute to the economic burden of this disease, with bladder cancer having the highest lifetime cost per patient of all cancers (Lee et al, 2012).

In Europe and North America, ∼90% of cases of bladder cancer are derived from the epithelial layer of the bladder and are termed transitional cell carcinomas (TCCs) (Luis et al, 2007). The majority (70–80%) of TCCs are confined to the bladder mucosa or lamina propria and are referred to as non-muscle-invasive cancers (NMIs). Muscle-invasive (MI) bladder cancer is defined by tumours that invade the muscularis propria and spread to the perivesical tissue and surrounding organs. The MI and NMI forms of bladder cancer have distinct underlying aetiologies, with NMI cancer characterised by increased expression and activating mutations of FGFR3, the PI3 kinase pathway and RAS (Castillo-Martin et al, 2010; Goebell and Knowles, 2010), and MI bladder cancer associated with mutations in TP53, RB and PTEN (Aveyard et al, 1999; Bakkar et al, 2003; van Rhijn et al, 2004).

Apart from somatic mutations intrinsic to cancer cells, additional factors play an important role in tumour growth including the extrinsic tumour microenvironment. A key feature of this microenvironment is hypoxia, a state of low oxygen tension. Hypoxia is an important component of tumourigenesis and a feature of most solid cancers. The cellular responses to hypoxia are mediated by the transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), an obligate dimer of α (HIF-1α) and β (HIF-1β) subunits. The active HIF complex binds to hypoxia response elements (HREs) of target genes leading to their transcriptional upregulation. Hypoxia-induced genes regulate many biological processes such as CA9 involved in pH regulation, VEGF involved in angiogenesis and LDHA involved in metabolism.

Regions of hypoxia have been demonstrated in both NMI and MI bladder tumours, with colocalisation of the hypoxic markers CA9 and VEGF seen on the luminal surface of NMI tumours and around the periphery of necrotic areas and in hypoxic cores in larger invasive tumours (Turner et al, 2002; Theodoropoulos et al, 2004). Levels of HIF-1α expression correlate with VEGF expression, microvessel density and ki67 proliferation index, supporting the role of the hypoxic response in various tumourigenic processes described in NMI and MI bladder cancer such as angiogenesis and proliferation (Jones et al, 2001; Chai et al, 2008).

An important class of regulators of gene expression are microRNAs (miRNAs). MicroRNAs are small (18–22 nucleotides), noncoding, single-stranded RNA that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression. The loss of components of the miRNA processing machinery, including the double-stranded RNA-binding protein DGCR8 (Hsu et al, 2012) and the RNase DICER (Bernstein et al, 2003), results in embryonic lethality in mice as well as defects in neuronal development, demonstrating the importance of the RNAi pathway in development and tissue homeostasis (Bauersachs and Thum, 2011). In addition, changes in miRNA expression occur in the majority of human tumours (Volinia et al, 2006) and miRNAs have been implicated in all the hallmarks of cancer (Lee et al, 2007; Cole et al, 2008; Xiao et al, 2008).

Hypoxia-regulated miRNAs (HRMs) have been identified in many cancer types. The miR-210 is currently acknowledged as the most robust HRM and is consistently upregulated as a result of HIF activation across a number of different tumour types including renal and head and neck cancers (Gee et al, 2010; Neal et al, 2010). Additional HRMs include miR-155 (Hua et al, 2006; Babar et al, 2011; Bruning et al, 2011) and miR-424 (Ghosh et al, 2010), although these appear to be regulated in a cell line-dependent manner.

The characterisation of miRNAs differentially regulated in bladder cancer has been the focus of recent studies aimed at establishing a role for miRNAs as diagnostic and prognostic markers. The miR-23b and miR-221 were found to be differentially regulated between the normal bladder urothelium and bladder tumours (Gottardo et al, 2007). Furthermore, the ratio between miR-21 and miR-205 may differentiate between invasive and noninvasive bladder cancer (Neely et al, 2010).

We have previously shown that miR-100 expression is decreased in bladder cancer compared with the normal urothelium (Catto et al, 2009). In addition, we have found that miR-100 levels are suppressed by hypoxia and that both hypoxia and miR-100 are responsible for regulating FGFR3 levels in NMI bladder cancer cell lines (Blick et al, 2013). However, to date, no comprehensive analysis has been performed to identify HRMs in bladder cancer. The initial aim of this study was to identify HRM signatures in NMI and MI bladder cancer. Furthermore, we go on to demonstrate that one of the miRNA in the signature, miR-145, is a bona fide HIF target in NMI bladder cancer and show that it plays a role in controlling cell viability after sustained exposure to hypoxia.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The cell lines RT4, RT112, T24 and HT1376 were obtained from Cancer Research UK Cell Services (Clare Hall Laboratories, London, UK) and cultured as previously described (Blick et al, 2013). A hypoxia incubator (MiniGalaxy A, RS Biotech, Irvine, Scotland) or hypoxia workstation (In Vivo2, Ruskinn Technology, Bridgend, UK) were used to achieve low oxygen conditions (1% or 0.1% O2 respectively) in parallel to cells maintained in normoxic conditions (5% CO2, 37 °C, 21% O2) for the indicated time. All experiments were done in triplicate from independent cell cultures.

RNA extraction, reverse transcription and quantitative PCR (qPCR) for microRNAs

Cells were lysed with Tri Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), and RNA extracted using chloroform followed by ethanol precipitation. RNA (350 ng) was reverse transcribed using the TaqMan Megaplex Primer Pool A mix and the TaqMan Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK). The miRNA expression was assayed on either the TaqMan Array Human MicroRNA A Card or using individual assays (Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR runs were done on the 7900HT Fast Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). For each miRNA, each sample was assayed in triplicate. The miRNA expression was normalised using either RNU44 or RNU48 using the comparative Ct method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) and presented as fold change relative to expression in normoxia.

The siRNA, miRNA mimics and anti-miRs

The siRNAs against HIF-1α and HIF-2α have been previously described (Blick et al, 2013). The scramble (Scr) and siRNA sequence against p53 were synthesised by Eurogentec (Liege, Belgium) and are as follows: Scr: 5′-ACGACACGCAGGUCGUCAU-3′ and sip53: 5′-GACUCCAGUGGUAAUCUAC-3′. The miR-145 mimic (mimic-miR-145) and anti-miR (anti-miR-145) and appropriate controls were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA).

Transfection protocol

Cells were reverse transfected with siRNA, mimic-miR-145 or anti-miR-145 with Oligofectamine (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions as previously described (Blick et al, 2013).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIPs) were performed using the EZ-ChIP kit (Millipore, Watford, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, RT4 cells were either incubated in normoxia or 0.1% O2 for 24 h. Proteins were first crosslinked to DNA with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and excess formaldehyde was quenched with 125 mM glycine for 5 min. Cells were harvested by scraping and resuspended in SDS lysis buffer with protease inhibitors to get a cell suspension at 2 × 107 cells per ml. Genomic DNA was sheared using a Diagenode Bioruptor (Liège, Belgium) sonicator to get fragments sizes in the range of 250–750 bp. Sheared DNA was precleared with protein G beads and immunoprecipitations were performed with anti-HIF-1α and anti-RNA polymerase II antibodies using 100 μl of sheared DNA per antibody. After overnight incubation at 4 °C, antibodies with bound chromatin were purified with protein G beads, the protein/DNA complexes eluted and then the crosslinks reversed to release the sheared genomic DNA.

Primers

Primers were purchased from Invitrogen. The following primer pairs were used for the ChIP PCRs: miR-145 HRE1_F: 5′-GTGAATGAGGCCGTGAACAGAGAC-3′ and miR-145 HRE1_R: 5′-CATGTCCACGGTTCTAGTTTCTTG-3′; miR-145_HRE2_F: 5′-AGCACCGGGGGCAGGTCAAG-3′ and miR-145_HRE2_R: 5′-GGCATTTTTAAGCAGCTGGCACTG-3′; CA9_HRE_F: 5′-GTCCATGGCCCCGATAACCTTCTG-3′ and CA9_HRE_R: 5′-GGGGCAACCTCTGGGGATGGAC-3′; UBC_F: 5′-TTGCTGGCAAATATCAGACG-3′ and UBC_R: 5′-GCAAGACCATCACCCTTGAG-3′.

Flow cytometry

RT4 cells were reverse transfected with mimic-145 or anti-miR-145 and appropriate controls and either kept in normoxia or placed in 0.1% O2. On days 3, 4 and 5, cells were harvested with trypsin and pelleted. Cells were stained with annexin-V-AlexaFluor 647 (Invitrogen; 5 μl) and propidium iodide (Invitrogen; 50 μg ml−1) in 100 μl of annexin V binding buffer (BD Pharmagen, San Jose, CA, USA) for 15 min at room temperature. Subsequently, 400 μl of annexin V staining buffer was added to each sample, cells were placed on ice and analysed by flow cytometry using a Cyan ADP Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Data collection and analysis was performed using Summit version 1 (DAKO, Glostrop, Denmark).

Correlation of miRNA expression

We have previously characterised the expression of miR-210, miR-193b and miR-145 in 55 primary bladder cancer samples (both NMI and MI) and normal urothelium (n=20) by qPCR (Catto et al, 2009). The correlation of normalised expression of miR-145, miR-210 and miR-193b was investigated by linear regression.

Results

Hypoxia regulates both common and distinct miRNAs in MI and NMI bladder cancer

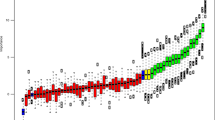

To generate HRM signatures in bladder cancer, the expression of 384 miRNAs in the TaqMan miRNA pool A were analysed in the noninvasive cell line RT4 and the invasive cell line T24 after exposure to normoxia or 0.1% hypoxia for 24 h. A number of criteria were used to refine the list of HRMs. First, miRNAs with CT values >40 in both normoxia and hypoxia were excluded as their expression levels were likely to be too low to accurately quantify. Second, attention was focussed on the 30 most up- or downregulated miRNAs for each cell line as these were likely to be true hits (Supplementary Figure 1). In agreement with other cell lines, miR-210 was robustly induced by hypoxia in both cell lines (Supplementary Figure 1). Seven of the 30 most hypoxia-upregulated miRNAs were common to both cell lines (Figure 1A). However, a number of the differentially regulated miRNAs were unique to each cell line (Figure 1A).

In RT4, miR-145 was the most robust HRM, being induced more strongly than miR-210 (Supplementary Figure 1 and Figure 1B). Furthermore, a number of miRNAs belonging to the C19MC cluster on chromosome 19 (Bortolin-Cavaille et al, 2009; Ren et al, 2009) including miR-518a-3p, 515-5p and 525-3p were also upregulated in response to hypoxia in this line. In T24, three members of the miR-200 family, including miR-200a, 200b and 200c, were upregulated in response to hypoxia (Supplementary Figure 1). Additional miRNAs upregulated in response to hypoxia in T24 cells included miR-150 and miR-15a. Across both cell lines, only 3 miRNAs were upregulated >10-fold in hypoxia: miR-145 and miR-210 in RT4 and miR-518f in T24 (Figure 1B).

Validation of low-density arrays reveals novel HRMs in bladder cancer cell lines

To validate the findings of the arrays, the expression of the following miRNAs was examined with individual assays – miRs 145, 518-3p, 125a-3p, 519d, 708, 525-3p, 517a, 519a, and miR-335 in RT4 and miRs 518f, 150, 200a, 15a, 99a, 107, 194 and 212 in T24. Validated targets in RT4 were also examined in a second NMI line, RT112, whereas confirmed targets in T24 were investigated in another MI line HT1376. The expression of miR-210 and miR-193b were examined in all cell lines.

The robust HRM miR-210 was induced after exposure to low oxygen in all bladder cancer cell lines (Figure 2A–D). In addition, miR-193b was also induced by hypoxia in all cell lines except HT1376 (Figure 2E–H). We also examined the expression of these two miRNAs in h-TERT, an immortalised normal urothelial cell line. Both miR-210 and miR-193b were upregulated by hypoxia in h-TERT cells, although the fold induction was lower than those observed in the bladder cancer cell lines (Supplementary Figure 2).

Validation of common HRMs in bladder cancer cell lines. Expression of (A–D) miR-210 and (E–H) miR-193b in (A and E) RT4, (B and F) T24, (C and G) RT112 and (D and H) HT1376 cells exposed to normoxia (N; white bars), 1% O2 (hatched bars) or 0.1% O2 (black bars) for the indicated time. Data are mean and s.e.m. of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

In addition to miR-145 (Figure 5), significant hypoxic upregulation of miR-518-3p, 125a-3p, 708, 517a, 519a and miR-335 was confirmed in RT4 cells (Figure 3A–F). MiR-525-3p and miR-519d were not significantly induced in response to hypoxia in RT4 cells (Figure 3G and H). In a second NMI bladder cancer line RT112, hypoxic induction of miR-145, 125-3p, miR-708 and miR-517a was observed (Supplementary Figure 3). The expression of miR-519a and miR-335 was unchanged by hypoxia (Supplementary Figure 3), whereas miR-518-3p was undetectable in these cells.

Validation of HRMs in RT4 cells. Expression of (A) miR-518-3p, (B) miR-125a-3p, (C) miR-519d, (D) miR-708, (E) miR-525-3p, (F) miR-517, (G) miR-519a and (H) miR-335 in RT4 cells exposed to normoxia (N; white bars), 1% O2 (hatched bars) or 0.1% O2 (black bars) for 24 h. Data are mean and s.e.m. of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Using individual assays, the hypoxic induction of miR-518f, 200a, 15a, 99a, 107, 194 and 212, but not miR-150, was confirmed in T24 (Figure 4). In a second MI cell line, HT1376, miR-15a, 99a and 107 were unchanged by exposure to hypoxia, miR-194 and 212 were suppressed (Supplementary Figure 4) and miR-518f and miR-200a were undetectable.

Validation of HRMs in T24 cells. Expression of (A) miR-518f, (B) miR-200a, (C) miR-99a, (D) miR-107, (E) miR-194, (F) miR-212, (G) miR-15a and (H) miR-150 in T24 cells exposed to normoxia (N; white bars), 1% O2 (hatched bars) or 0.1% O2 (black bars) for 24 h. Data are mean and s.e.m. of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Hypoxic upregulation of miR-145 requires HIF-1α but not p53

As mentioned previously, robust induction of miR-145 was observed in RT4 (Figures 1 and 5A ). MiR-145 was also induced upon treatment of cells with the hypoxia mimetic DMOG in normoxia (Figure 5B). The upregulation of miR-145 in RT4 was of particular interest as miR-145 can, in part, be regulated by p53 (Sachdeva et al, 2009). As RT4 cells have wild-type p53, we investigated whether p53 was required for the hypoxic induction of miR-145. Knockdown of p53 did not reduce miR-145 expression in hypoxia (Figure 5C). However, knockdown of p53 attenuated the hypoxic induction of miR-210 (Figure 5D).

Regulation of miR-145 by hypoxia and p53. (A) RT4 cells were cultured in normoxia (white bars), 1% O2 (hatched bars) or 0.1% O2 (black bars) for 24 h. (B) RT4 cells were cultured in normoxia (N; white bars), 0.1% O2 (black bars) or in normoxia and treated with DMOG (hatched bars) for 24 h. (C) Expression of miR-145 and (D) expression of miR-210 in RT4 cells cultured in normoxia (white bars) or 0.1% O2 (black bars) for 24h after transfection with scramble (Scr) siRNA or siRNA against HIF-1α or HIF-2α. Data are mean and s.e.m. of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

MiR-145 is a direct HIF-1α target gene

As the expression of miR-145 was induced by hypoxia and DMOG, we hypothesised that it was a direct HIF target gene in RT4 cells. Indeed, knockdown of HIF-1α but not HIF-2α attenuated the hypoxic induction of miR-145 (Figure 6A). A similar pattern of expression was observed for miR-210 (Figure 6B), a well-characterised HIF-1α target miRNA.

Role of HIF in miR-145 induction. Expression of (A) miR-145 and (B) miR-210 in RT4 cells cultured in normoxia (N; white bars) or 0.1% O2 (black bars) for 24 h after transfection with scramble (Scr) siRNA or siRNA against HIF-1α or HIF-2α. (C) The miR-145 is transcribed from a locus from which miR-143 is also processed. MatInspector identified two putative HIF response elements (HREs) in the genomic region upstream of the cognate transcript. (D) Chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIPs) were performed with antibodies against RNA polymerase (pol.) II or HIF-1α in RT4 cells exposed to normoxia (white bars) or 0.1% O2 (black bars) for 24 h. Individual primer pairs were designed against each of the two HREs in the miR-145 locus. Primers against the well-characterised HRE in CA9 was used as a positive control and primers against the upstream region of the constitutively expressed gene UBC was used as a negative control. (A and B) Data are mean and s.e.m. of three independent experiments, and (D) data are representative of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01

Using MatInspector (Cartharius et al, 2005), two putative HREs were identified in the promoter region of miR-145 (Figure 6C). To confirm that they were true HIF binding sites, ChIPs were performed with HIF-1α and RNA polymerase II antibodies. The HRE1, which is closer to the transcription start site (TSS) (Figure 6C), was enriched with both HIF-1α and RNA polymerase II antibodies (Figure 6D). The HRE2 that is 1.1 kb upstream of the TSS was only enriched with the HIF-1α antibody (Figure 6D). As a positive control, the HRE of the robust HIF-1α target gene CA9 was enriched with both the HIF-1α and RNA polymerase II antibodies (Figure 6D) and the negative control UBC was not enriched in normoxia or hypoxia with either antibody (Figure 6D). Therefore, the hypoxic induction of miR-145 appears to be a direct effect of HIF-1α dependent transactivation.

MiR-145 regulates apoptosis under hypoxia in RT4 cells

As overexpression of miR-145 has been shown to affect cell viability in bladder cancer lines (Chiyomaru et al, 2010), we investigated whether miR-145 may play a role in cell viability in hypoxia in RT4 cells. Transfection of mimic-miR-145 in normoxia led to an increase in apoptotic annexin V+/PI− cells and necrotic annexin V+/PI+ cells compared with mimic-ctrl transfected cells and a concomitant decrease in viable annexin V−/PI− cells (Figure 7A and B and Table 1).

Role of miR-145 in cell survival. RT4 cells were transfected with (A) mimic-ctrl and (B) mimic-145 and incubated in normoxia for 4 days. RT4 cells were transfected with (C and D) anti-miR-ctrl and (E) anti-miR-145 and incubated in (C) normoxia or (D and E) 0.1% O2 for 5 days. The x axis indicates PI staining and y axis indicates annexin V staining. (A–E) Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Exposure of anti-miR-ctrl transfected cells to hypoxia led to a decrease in cell viability as seen by an increase in necrotic annexin V+/PI+ cells and a decrease in viable annexin V−/PI− cells (Figure 7C and D and Table 1). Importantly, transfection of anti-miR-145 improved cell viability in hypoxia, with a decrease in annexin V+/PI+ cells and an increase in annexin V−/PI− cells (Figure 7E and Table 1). Thus, the hypoxic upregulation of miR-145 contributes to cell death under hypoxia in RT4 cells.

MiR-145 expression correlates with that of miR-210 and miR-145 in primary bladder cancer specimen

To determine the biological relevance of HRMs in vivo, we examined the correlation of miR-145, miR-210 and miR-193b expression in primary bladder cancer samples and in the normal bladder urothelium. The expression of miR-193b was strongly correlated to that of miR-145 (Figure 8A) and miR-210 (Figure 8B); the expression of miR-145 did not correlate to the expression of miR-210 in vivo (Figure 8C).

Discussion

Variations in gene expression among different tumour types led us to hypothesise that exposure to hypoxia may lead to changes in miRNA expression that are unique to bladder cancer. Of the 25 miRNAs most highly induced in RT4 and T24, two cell lines that represent NMI and MI bladder cancer types respectively, the majority were exclusive to one or other. This is likely because of the differences between the molecular pathways involved in the two forms of bladder cancer that these two cell lines represent. Seven miRNAs were induced by hypoxia in both cell lines. They include the universal HRM miR-210 (Kulshreshtha et al, 2007; Camps et al, 2008) and miR-193b that is induced by hypoxia in the colon cancer line CaCo2 (Bruning et al, 2011). Thus, these may represent cell type-independent targets of HIF but further validation, particularly of miR-193b, is required. The fold induction of miR-210 in hypoxia was lower in the immortalised urothelium line h-TERT compared with the cancer-derived cell lines. This could reflect differences between cell lines or may suggest that the hypoxic response in cancer cells is augmented by additional pathways such as mTOR (Hudson et al, 2002).

Of note was the hypoxic induction of co-regulated miRNAs. Both miRNAs derived from pre-miR-125a, miR-125a-3p and miR-125a-5p (Jiang et al, 2010) were induced by hypoxia in RT4 and T24 cells. Furthermore, almost half of the 25 most hypoxia-induced miRNAs in RT4 cells, including miR-518a-3p, 515-5p and 525-3p, are from the primate-specific C19MC cluster on chromosome 19 (Bortolin-Cavaille et al, 2009). The induction of more than one miRNA from a precursor/cluster strengthens the notion that these are bona fide HRMs.

The hypoxic induction of miR-145, miR-125-3p, miR-708 and miR-517a was common to both NMI bladder cancer cell lines (RT4 and RT112). These four miRNAs, along with miR-210 and miR-193b, may form part of a HRM signature for NMI bladder cancer. Indeed, significant correlation was observed between miR-193b expression and that of miR-145 and miR-210 in NMI bladder cancer samples in vivo. In contrast, the majority of hypoxia-induced miRNAs in T24 cells could not be ratified in a second invasive bladder cancer line HT1376. Thus, MI bladder cancer-derived cell lines respond to hypoxia in a more varied manner, suggesting they are more divergent from each other.

Members of the miR-200 family, associated with EMT, have been found to be downregulated in advanced bladder cancer (Wiklund et al, 2011).

In RT4 cells, the hypoxic induction of miR-145 was dependent on HIF-1α with two HREs identified in the promoter region. MiR-145, thus, represents a new HIF-1α target gene in NMI bladder cancer lines and a novel HRM. The expression of miR-145 is known to be regulated by p53 (Sachdeva et al, 2009). However, in RT4 cells that have wild-type p53, knockdown of p53 did not affect the hypoxic induction of miR-145. In ovarian cancer, the presence of a nonfunctioning p53 has been shown to be critical for miR-145 to fail in its role as a tumour suppressor (Dong et al, 2014). In contrast, knockdown of p53 attenuated the hypoxic induction of miR-210. The HIF-1α has previously been shown to stabilise and activate wild-type p53 (An et al, 1998) and, as seen in our hands, loss of p53 attenuated the hypoxic induction of miR-210 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Mutharasan et al, 2011). The synergy and crosstalk between HIF and p53 warrants further investigation.

The miRNA cluster 143-145 has been found to be downregulated in many cancer types and is considered a tumour suppressor in ovarian, breast and pancreatic cancers (Dong et al, 2014; Khan et al, 2014; Yan et al, 2014). The locus is suppressed by RAS signalling (Kent et al, 2010; Sachdeva and Mo, 2010). In bladder cancer, immunohistochemistry of miR-145 showed homogenous but reduced staining compared with normal tissue in papillary tumours, heterogenous expression in MI tumours and no staining in carcinoma in situ (Ostenfeld et al, 2010). The miR-145 is downregulated in invasive bladder tumours and described as a tumour suppressor (Yoshino et al, 2013). It has also been shown to inhibit invasion in bladder cancer by targeting PAK1 (Kou et al, 2014) and inhibit bladder cancer initiation by targeting IGFR1(Zhu et al, 2014). Additional validated targets of miR-145 include C-MYC (Sachdeva et al, 2009), OCT4, SOX2 and KLF4 (Xu et al, 2009), thereby suppressing tumour growth and stem cell renewal. Conversely, overexpression of miR-145 suppresses growth and invasion in breast cancer cell lines (Kent et al, 2010; Sachdeva and Mo, 2010). Furthermore, miR-145 has been shown to lead to caspase-dependent and -independent cell death in bladder cancer cell lines (Chiyomaru et al, 2010; Ostenfeld et al, 2010; Noguchi et al, 2013). The miR-145 has also been shown to regulate PAI-1, an oncogene associated with a poor prognosis in bladder cancer, suggesting miR-145 may have a role as a prognostic indicator. In agreement with this, in this study, we have shown that increased levels of miR-145 in hypoxia contribute to cell death of RT4 cells. It is possible that one of the adaptive mechanisms in more malignant cancer types is the loss of hypoxic induction of miR-145, thus providing a survival advantage to cells.

In conclusion, we have shown that a relatively small-scale analysis can deliver novel insights into hypoxia biology. We have identified a number of miRNAs that could form part of a HRM signature, particularly in NMI bladder cancer. This strategy is capable of identifying direct HIF target genes, as demonstrated by miR-145. Finally, hypoxia-induced miRNAs are functionally relevant, as we have shown that miR-145 controls apoptosis in NMI bladder cancer cell lines. It may be worthwhile to validate the HRM signature identified herein in a larger cohort of NMI bladder cancer samples.

Change history

11 August 2015

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

An WG, Kanekal M, Simon MC, Maltepe E, Blagosklonny MV, Neckers LM (1998) Stabilization of wild-type p53 by hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Nature 392: 405–408.

Aveyard JS, Skilleter A, Habuchi T, Knowles MA (1999) Somatic mutation of PTEN in bladder carcinoma. Br J Cancer 80: 904–908.

Babar IA, Czochor J, Steinmetz A, Weidhaas JB, Glazer PM, Slack FJ (2011) Inhibition of hypoxia-induced miR-155 radiosensitizes hypoxic lung cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther 12: 908–914.

Bakkar AA, Wallerand H, Radvanyi F, Lahaye JB, Pissard S, Lecerf L, Kouyoumdjian JC, Abbou CC, Pairon JC, Jaurand MC, Thiery JP, Chopin DK, de Medina SG (2003) FGFR3 and TP53 gene mutations define two distinct pathways in urothelial cell carcinoma of the bladder. Cancer Res 63: 8108–8112.

Bauersachs J, Thum T (2011) Biogenesis and regulation of cardiovascular microRNAs. Circ Res 109: 334–347.

Bernstein E, Kim SY, Carmell MA, Murchison EP, Alcorn H, LI MZ, Mills AA, Elledge SJ, Anderson KV, Hannon GJ (2003) Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat Genet 35: 215–217.

Blick C, Ramachandran A, Wigfield S, Mccormick R, Jubb A, Buffa FM, Turley H, Knowles MA, Cranston D, Catto J, Harris AL (2013) Hypoxia regulates FGFR3 expression via HIF-1alpha and miR-100 and contributes to cell survival in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Br J Cancer 109: 50–59.

Bortolin-Cavaille ML, Dance M, Weber M, Cavaille J (2009) C19MC microRNAs are processed from introns of large Pol-II, non-protein-coding transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res 37: 3464–3473.

Bruning U, Cerone L, Neufeld Z, Fitzpatrick SF, Cheong A, Scholz CC, Simpson DA, Leonard MO, Tambuwala MM, Cummins EP, Taylor CT (2011) MicroRNA-155 promotes resolution of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha activity during prolonged hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol 31: 4087–4096.

Camps C, Buffa FM, Colella S, Moore J, Sotiriou C, Sheldon H, HARRIS AL, Gleadle JM, Ragoussis J (2008) hsa-miR-210 Is induced by hypoxia and is an independent prognostic factor in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 14: 1340–1348.

Cartharius K, Frech K, Grote K, Klocke B, Haltmeier M, Klingenhoff A, Frisch M, Bayerlein M, Werner T (2005) MatInspector and beyond: promoter analysis based on transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics 21: 2933–2942.

Castillo-Martin M, Domingo-Domenech J, Karni-Schmidt O, Matos T, Cordon-Cardo C (2010) Molecular pathways of urothelial development and bladder tumorigenesis. Urol Oncol 28: 401–408.

Catto JW, Miah S, Owen HC, Bryant H, Myers K, Dudziec E, Larre S, Milo M, Rehman I, Rosario DJ, di Martino E, Knowles MA, Meuth M, Harris AL, Hamdy FC (2009) Distinct microRNA alterations characterize high- and low-grade bladder cancer. Cancer Res 69: 8472–8481.

Chai CY, Chen WT, Hung WC, Kang WY, Huang YC, SU YC, Yang CH (2008) Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha expression correlates with focal macrophage infiltration, angiogenesis and unfavourable prognosis in urothelial carcinoma. J Clin Pathol 61: 658–664.

Chiyomaru T, Enokida H, Tatarano S, Kawahara K, Uchida Y, Nishiyama K, Fujimura L, Kikkawa N, Seki N, Nakagawa M (2010) miR-145 and miR-133a function as tumour suppressors and directly regulate FSCN1 expression in bladder cancer. Br J Cancer 102: 883–891.

Cole KA, Attiyeh EF, Mosse YP, Laquaglia MJ, Diskin SJ, BRODEUR GM, Maris JM (2008) A functional screen identifies miR-34a as a candidate neuroblastoma tumor suppressor gene. Mol Cancer Res 6: 735–742.

Dong R, LIU X, Zhang Q, Jiang Z, LI Y, Wei Y, Yang Q, Liu J, Wei JJ, Shao C, Liu Z, Kong B (2014) miR-145 inhibits tumor growth and metastasis by targeting metadherin in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Oncotarget 5: 10816–10829.

Gee HE, Camps C, Buffa FM, Patiar S, Winter SC, Betts G, Homer J, Corbridge R, Cox G, West CM, Ragoussis J, Harris AL (2010) hsa-mir-210 is a marker of tumor hypoxia and a prognostic factor in head and neck cancer. Cancer 116: 2148–2158.

Ghosh G, Subramanian IV, Adhikari N, Zhang X, Joshi HP, Basi D, Chandrashekhar YS, Hall JL, Roy S, Zeng Y, Ramakrishnan S (2010) Hypoxia-induced microRNA-424 expression in human endothelial cells regulates HIF-alpha isoforms and promotes angiogenesis. J Clin Invest 120: 4141–4154.

Goebell PJ, Knowles MA (2010) Bladder cancer or bladder cancers? Genetically distinct malignant conditions of the urothelium. Urol Oncol 28: 409–428.

Gottardo F, LIU CG, Ferracin M, Calin GA, Fassan M, Bassi P, Sevignani C, Byrne D, Negrini M, Pagano F, Gomella LG, Croce CM, Baffa R (2007) Micro-RNA profiling in kidney and bladder cancers. Urol Oncol 25: 387–392.

Hsu R, Schofield CM, Dela CRUZ CG, Jones-Davis DM, Blelloch R, Ullian EM (2012) Loss of microRNAs in pyramidal neurons leads to specific changes in inhibitory synaptic transmission in the prefrontal cortex. Mol Cell Neurosci 50: 283–292.

Hua Z, Lv Q, Ye W, Wong CK, Cai G, Gu D, Ji Y, Zhao C, Wang J, Yang BB, Zhang Y (2006) MiRNA-directed regulation of VEGF and other angiogenic factors under hypoxia. PLoS One 1: e116.

Hudson CC, Liu M, Chiang GG, Otterness DM, Loomis DC, Kaper F, Giaccia AJ, Abraham RT (2002) Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha expression and function by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Mol Cell Biol 22: 7004–7014.

Jiang L, Huang Q, Zhang S, Zhang Q, Chang J, Qiu X, Wang E (2010) Hsa-miR-125a-3p and hsa-miR-125a-5p are downregulated in non-small cell lung cancer and have inverse effects on invasion and migration of lung cancer cells. BMC Cancer 10: 318.

Jones A, Fujiyama C, Blanche C, Moore JW, Fuggle S, Cranston D, Bicknell R, Harris AL (2001) Relation of vascular endothelial growth factor production to expression and regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha and hypoxia-inducible factor-2 alpha in human bladder tumors and cell lines. Clin Cancer Res 7: 1263–1272.

Kent OA, Chivukula RR, Mullendore M, Wentzel EA, Feldmann G, Lee KH, Liu S, Leach SD, Maitra A, Mendell JT (2010) Repression of the miR-143/145 cluster by oncogenic Ras initiates a tumor-promoting feed-forward pathway. Genes Dev 24: 2754–2759.

Khan S, Ebeling MC, Zaman MS, Sikander M, Yallapu MM, Chauhan N, Yacoubian AM, Behrman SW, Zafar N, Kumar D, Thompson PA, Jaggi M, Chauhan SC (2014) MicroRNA-145 targets MUC13 and suppresses growth and invasion of pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget 5: 7599–7609.

Kou B, Gao Y, Du C, Shi Q, Xu S, Wang CQ, Wang X, He D, Guo P (2014) miR-145 inhibits invasion of bladder cancer cells by targeting PAK1. Urol Oncol 32: 846–854.

Kulshreshtha R, Ferracin M, Wojcik SE, Garzon R, Alder H, Agosto-Perez FJ, Davuluri R, Liu CG, Croce CM, Negrini M, Calin GA, Ivan M (2007) A microRNA signature of hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol 27: 1859–1867.

Lee CT, Barocas D, Globe DR, Oefelein MG, Colayco DC, Bruno A, O'day K, Bramley T (2012) Economic and humanistic consequences of preventable bladder tumor recurrences in nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer cases. J Urol 188: 2114–2119.

Lee DY, Deng Z, Wang CH, Yang BB (2007) MicroRNA-378 promotes cell survival, tumor growth, and angiogenesis by targeting SuFu and Fus-1 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 20350–20355.

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25: 402–408.

Luis NM, Lopez-Knowles E, Real FX (2007) Molecular biology of bladder cancer. Clin Transl Oncol 9: 5–12.

Mutharasan RK, Nagpal V, Ichikawa Y, Ardehali H (2011) microRNA-210 is upregulated in hypoxic cardiomyocytes through Akt- and p53-dependent pathways and exerts cytoprotective effects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H1519–H1530.

Neal CS, Michael MZ, Rawlings LH, van der Hoek MB, Gleadle JM (2010) The VHL-dependent regulation of microRNAs in renal cancer. BMC Med 8: 64.

Neely LA, Rieger-Christ KM, Neto BS, Eroshkin A, Garver J, Patel S, Phung NA, Mclaughlin S, Libertino JA, Whitney D, Summerhayes IC (2010) A microRNA expression ratio defining the invasive phenotype in bladder tumors. Urol Oncol 28: 39–48.

Noguchi S, Yamada N, Kumazaki M, Yasui Y, Iwasaki J, Naito S, Akao Y (2013) socs7, a target gene of microRNA-145, regulates interferon-beta induction through STAT3 nuclear translocation in bladder cancer cells. Cell Death Dis 4: e482.

Office for National Statistics (2010) Cancer statistics–registrations, England, 2007. Series MB1 No.37. London.

Ostenfeld MS, Bramsen JB, Lamy P, Villadsen SB, Fristrup N, Sorensen KD, Ulhoi B, Borre M, Kjems J, Dyrskjot L, Orntoft TF (2010) miR-145 induces caspase-dependent and -independent cell death in urothelial cancer cell lines with targeting of an expression signature present in Ta bladder tumors. Oncogene 29: 1073–1084.

Ren J, Jin P, Wang E, Marincola FM, Stroncek DF (2009) MicroRNA and gene expression patterns in the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. J Transl Med 7: 20.

Sachdeva M, Mo YY (2010) MicroRNA-145 suppresses cell invasion and metastasis by directly targeting mucin 1. Cancer Res 70: 378–387.

Sachdeva M, Zhu S, Wu F, Wu H, Walia V, Kumar S, Elble R, Watabe K, Mo YY (2009) p53 represses c-Myc through induction of the tumor suppressor miR-145. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 3207–3212.

Theodoropoulos VE, Lazaris A, Sofras F, Gerzelis I, Tsoukala V, Ghikonti I, Manikas K, Kastriotis I (2004) Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha expression correlates with angiogenesis and unfavorable prognosis in bladder cancer. Eur Urol 46: 200–208.

Turner KJ, Moore JW, Jones A, Taylor CF, Cuthbert-Heavens D, Han C, Leek RD, Gatter KC, Maxwell PH, Ratcliffe PJ, Cranston D, Harris AL (2002) Expression of hypoxia-inducible factors in human renal cancer: relationship to angiogenesis and to the von Hippel-Lindau gene mutation. Cancer Res 62: 2957–2961.

van Rhijn BW, Burger M, Lotan Y, Solsona E, Stief CG, Sylvester RJ, Witjes JA, Zlotta AR (2009) Recurrence and progression of disease in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: from epidemiology to treatment strategy. Eur Urol 56: 430–442.

van Rhijn BW, van der Kwast TH, Vis AN, Kirkels WJ, Boeve ER, Jobsis AC, Zwarthoff EC (2004) FGFR3 and P53 characterize alternative genetic pathways in the pathogenesis of urothelial cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 64: 1911–1914.

Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F, Visone R, Iorio M, Roldo C, Ferracin M, Prueitt RL, Yanaihara N, Lanza G, Scarpa A, Vecchione A, Negrini M, Harris CC, Croce CM (2006) A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 2257–2261.

Wiklund ED, Bramsen JB, Hulf T, Dyrskjot L, Ramanathan R, Hansen TB, Villadsen SB, Gao S, Ostenfeld MS, Borre M, Peter ME, Orntoft TF, Kjems J, Clark SJ (2011) Coordinated epigenetic repression of the miR-200 family and miR-205 in invasive bladder cancer. Int J Cancer 128: 1327–1334.

Xiao C, Srinivasan L, Calado DP, Patterson HC, Zhang B, Wang J, Henderson JM, Kutok JL, Rajewsky K (2008) Lymphoproliferative disease and autoimmunity in mice with increased miR-17-92 expression in lymphocytes. Nat Immunol 9: 405–414.

Xu N, Papagiannakopoulos T, Pan G, Thomson JA, Kosik KS (2009) MicroRNA-145 regulates OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 and represses pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Cell 137: 647–658.

Yan X, Chen X, Liang H, Deng T, Chen W, Zhang S, Liu M, Gao X, Liu Y, Zhao C, Wang X, Wang N, Li J, Liu R, Zen K, Zhang CY, Liu B, Ba Y (2014) miR-143 and miR-145 synergistically regulate ERBB3 to suppress cell proliferation and invasion in breast cancer. Mol Cancer 13: 220.

Yoshino H, Seki N, Itesako T, Chiyomaru T, Nakagawa M, Enokida H (2013) Aberrant expression of microRNAs in bladder cancer. Nat Rev Urol 10: 396–404.

Zhu Z, Xu T, Wang L, Wang X, Zhong S, Xu C, Shen Z (2014) MicroRNA-145 directly targets the insulin-like growth factor receptor I in human bladder cancer cells. FEBS Lett 588: 3180–3185.

Acknowledgements

Work in this laboratory is supported by grants from Cancer research UK and the NHIR Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford. CB received grants from The Royal College of Surgeons of England, UCARE and The Urology Foundation. AR was funded by the Nuffield Dominion Trust.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Blick, C., Ramachandran, A., McCormick, R. et al. Identification of a hypoxia-regulated miRNA signature in bladder cancer and a role for miR-145 in hypoxia-dependent apoptosis. Br J Cancer 113, 634–644 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.203

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.203

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

MiR-122-5p regulates the mevalonate pathway by targeting p53 in non-small cell lung cancer

Cell Death & Disease (2023)

-

MicroRNA-18a regulates the metastatic properties of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells via HIF-1α expression

BMC Oral Health (2022)

-

Effects of hypoxia and reoxygenation on mitochondrial functions and transcriptional profiles of isolated brain and muscle porcine cells

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

A miRNA signature predicts benefit from addition of hypoxia-modifying therapy to radiation treatment in invasive bladder cancer

British Journal of Cancer (2021)

-

The interplay between HIF-1α and noncoding RNAs in cancer

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2020)