Abstract

The determinants of childhood overweight and obesity are complex, but infant feeding and the early diet are important contributing factors. The complementary feeding period in particular, is a time during which children are nutritionally vulnerable, and a time where life-long eating habits may be established. We conducted a systematic review of the literature that investigated the relationship between the types of food consumed by infants during the complementary feeding period and overweight or obesity during childhood. Electronic databases were searched from inception until June 2012 using specified keywords. Following the application of strict inclusion/exclusion criteria, 10 studies were identified and reviewed by two independent reviewers. Data were extracted and aspects of quality were assessed using an adapted Newcastle–Ottawa scale. Studies were categorised into three groups: macronutrient intake, food type/group and adherence to dietary guidelines. Some association was found between high protein intakes at 2–12 months of age and higher body mass index (BMI) or body fatness in childhood, but was not the case in all studies. Higher energy intake during complementary feeding was associated with higher BMI in childhood. Adherence to dietary guidelines during weaning was associated with a higher lean mass, but consuming specific foods or food groups made no difference to children’s BMI. We concluded that high intakes of energy and protein, particularly dairy protein, in infancy could be associated with an increase in BMI and body fatness, but further research is needed to establish the nature of the relationship. Adherence to dietary guidelines during weaning is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Overweight and obesity is a major public health concern in most developed countries, and in adults is a cause of diseases including cardiovascular diseases, type II diabetes and some cancers.1 The International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) estimated that up to 200 million school-aged children were overweight or obese in 2010, including up to 20% of all children in the European Union.2 Altogether, 43–60% of children who were obese before puberty will be obese as adults (rising to 47–90% of those who were obese as adolescents being obese in adulthood). Reducing the prevalence of obesity amongst children may, therefore, help to reduce the burden of morbidity and mortality caused by obesity-related illness in the adult population.3 The causes of childhood obesity are complex, and many factors influence growth, body mass index (BMI) and body composition. An unhealthy diet, lack of exercise, food advertising, an increase in the hours engaged in sedentary activities and ‘screen time’, such as watching television and using computers, create an increasingly obesiogenic environment for children in developed countries.4, 5, 6 Parental factors such as low socioeconomic status, fewer years spent in education, higher BMI and less meals eaten together as a family can also contribute to overweight and obesity in children.7, 8, 9, 10

Diet during infancy and early childhood is one such area where parental choice may have significant long-term effects on a child’s weight status. Breast-fed, as compared to formula-fed infants, have a lower BMI during childhood, although the results of meta-analyses have varied.11 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommend that all babies are exclusively breastfed until 6 months of age, at which time, breast milk should continue to provide a substantial contribution to children’s energy and nutrient intake, but alone, will not be enough to meet the infants’ requirements.12 Current UK advice on complementary feeding states that at around 6 months of age, babies are ready to be moved on to a mixed diet and recommends introducing vegetables, fruits or cereal mixed with milk (breast or formula milk) as first foods, followed by meat, chicken, fish, rice, pasta, lentils, pulses and full-fat dairy products once the baby has become used to those first foods.13 The use of finger foods is encouraged in the guidance and whilst meal/menu plans and recommended serving sizes are not given, advice is available on the frequency with which food groups should be provided, that is, three–four servings daily of starchy food (such as potato, bread and rice). By 9 months, the guidance recommends that a baby should fit in with the rest of the family by eating three minced or chopped meals a day as well as milk, and by 12 months, most infants should be consuming a modified version of the family diet.13 At present, little evidence exists as to the effect on childhood BMI or body composition of the types of food given to children during the complementary feeding period. This systematic review aims to look at the body of evidence surrounding the impact of the types of food given during the complementary feeding period on BMI or body composition in children aged 4–12 years. The effects of timing of the introduction of complementary foods has been considered in a separate review (paper submitted14).

Materials and methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We carried out a review of the literature to identify published studies that investigated the association between the types of food used during the complementary feeding period and the risk of childhood overweight or obesity. To find articles, a computerised search of the online databases PubMed (MEDLINE), ISI Web of Science and Scopus Sciverse, including all studies up to the end of June 2012, was carried out using the MeSH terms ‘weaning’, ‘complementary food’ and ‘supplementary food’ combined with ‘obesity’ and ‘body composition’. Search fields were left as open as possible to maximise the number of articles found; ‘All fields’ (PubMed), ‘Article title, abstract, keywords’ (Scopus Sciverse) and ‘topic’ (ISI Web of Science). To select studies for inclusion in the review, (1) the list of articles obtained via the search was screened to exclude non-relevant studies and to remove duplicates of those articles identified by two or more databases, (2) the abstracts (3) the full texts of the remaining articles were read in full and screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed below and (4) additional studies, identified by hand searching of the bibliographies of those papers that met the selection criteria were examined as per steps (2) and (3). Both authors completed all stages of the review in parallel.

The inclusion criteria were:

-

1

Exposure variable: a measure of the types of food or nutrients given to infants during the period of introduction of complementary feeding (up to and including 12 months of age). This could be dietary intake (food group or nutrient intake) or adherence to dietary guidelines, and must have been reported during the complementary feeding period (up to and including 12 months of age). The method by which dietary/food intake was recorded should be stated but may be reported by the parent/carer.

-

2

Outcome variable: childhood measures of BMI or percentage body fat at one or more ages of childhood (at a mean age of 4–12 years old). All measurements used to calculate BMI should have been taken by health professionals or trained investigators (not self-reported).

-

3

Measurements should be cross-sectional or in the case of case-control or cohort studies, must have been carried out in the same individuals at baseline and at follow-up.

-

4

Childhood BMI status should be calculated using either US Center for Disease Control and prevention (CDC) percentile charts15 or IOTF charts.16 Childhood overweight and obese must be defined as within those criterion (CDC: >85th centile at risk of overweight, >95th centile obese; IOTF percentiles track back from WHO Adult guidelines:17⩾25 kg/m2 overweight and⩾30 kg/m2 obese) or childhood BMI status should be treated as a continuous variable and association with adult outcome assessed by regression or correlation.

-

5

Studies must be reported in the English language.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

1

Studies on animals.

-

2

Intervention studies, for example; studies where the participants were part of an obesity intervention, health promotion intervention or child-feeding programme.

-

3

Studies where the individuals involved were all part of a selected group, for example, childhood cancer survivors, preterm babies or diabetes sufferers.

-

4

Childhood overweight or obese defined using arbitrary cutoff points.

-

5

Reviews or systematic reviews, rather than original data.

-

6

Studies where height, weight, BMI or other measures excluding dietary intake were self-reported.

-

7

Meeting abstracts, posters, letters or commentaries.

Two investigators (JP and SCLE) independently searched for and reviewed studies for inclusion in the review, using the inclusion/exclusion criteria listed previously. Agreement was good (κ=0.727), and any differences were discussed and agreed by consensus. Figure 1 shows the searching and selection process, and the number of articles that were excluded at each stage.

Data extraction and analyses

Data relating to the population characteristics, exposure and outcome variables were extracted (Table 1). Where necessary, further data or explanation of data analyses were sought from the authors of the studies. The results of studies were not combined in a meta-analysis due to the considerable heterogeneity of the methodologies and analyses presented by the different authors.

Quality assessment

The quality of the papers that were identified for inclusion in the review was assessed using an adapted 10-point Newcastle–Ottawa scale (Table 2) for case-control or cohort studies. The scale was designed specifically for non-randomised studies and can be used to assess study quality against criteria relating to aspects of study design.18 The quality of each study was assessed and awarded stars for indicators of quality (Table 3), including selection of the study population, comparability to other studies and the assessment of the outcome of interest. No case-control studies were identified for this review, therefore, the scale (Table 2) was developed for cohort studies only.

Exposure

The studies included in the review used a variety of methods and tools to measure infants’ exposure to complementary foods. Gunnarsdottir and Thorsdottir,19 Gunther et al.20, 21 and Hoppe et al.22 used 24/48 h, 3 days and 5 days22 parent/carer-completed weighed records, respectively, (including household measures where weights were not possible). In the studies by Gunnarsdottir and Thorsdottir19 and Gunther et al.20, 21 nutrient intake from either breast milk or formula milk was calculated by weighing the infant before and after feeding to measure the weight of milk consumed accurately. The amount of milk consumed was then added into the programme computing nutrient intake from all sources of food and drink. Hoppe et al.22 did not describe how the intake of milk was calculated. Ong et al.23 used a parent/carer-completed unweighed structured 1-day record with records of the length of time of each breastfeed, and estimation of portion sizes using household measures and average portion size data.24 Robinson et al.25 used a food frequency questionnaire for the previous month to assess adherence to dietary guidelines, whereas the four studies assessing food type/group used retrospective infant-feeding questionnaires to determine the types and timing of foods consumed by children between and 6 years old.26, 27, 28, 29

Outcome measures

The outcomes in children were BMI, BMI z-score or percentage body fat (% BF) as a continuous variable or IOTF,16 US CDC17 or WHO weight-for-length and weight-for-age cutoff values as categorical variables.30 Percentage body fat was measured by dual X-ray absorptiometry or estimated from skinfold thickness measurements taken from two or more sites (biceps, triceps, subscapular or suprailiac) using callipers.

Results

Description of the included studies

A total of 10 articles fulfilled the selection criteria, and the characteristics and results of each study are summarised in Table 1. Data were collected between 1959 and 2009, but published in the last 10 years. Children were followed up at ages ranging from 4 to 11 years, although one study continued to follow participants until 42 years of age.28 Data were collected in Brazil (two studies), Denmark (two studies), Germany (two studies), Iceland, Palestine and the United Kingdom (two studies). Most of the cohorts were born to women that were truly representative of the local population, apart from Schack-Nielsen et al.,28 who recruited women who attended hospital at a time when home births were advisable unless high risk (that is, mothers in the study were more likely to have had complicated births). Typically, the studies included only healthy individuals19, 20, 21, 22 or all the live births within a selected area, region, hospital or group of hospitals.22, 23, 25, 27, 28 The remaining studies were retrospective studies that selected individuals following a random sampling plan.26, 29

The number of children taking part at follow-up ranged from 90 to 881 participants, and male participants made up between 46 and 55% of the study populations.

Quality assessment

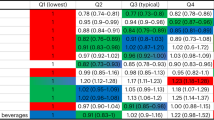

Based on the selection of the study population, eight studies achieved three stars, whereas Kanoa et al.26 were not able to demonstrate that overweight/obese children were not overweight or obese at the time of exposure, and the population studied by Schack-Neilsen et al.28 could not be considered truly representative of a contemporary western population of children, due to the date of exposure and differences in the types of weaning food (gruel and soaked bread/biscuits) and breast milk substitute (cow milk with added barley water and sugar or a commercial buttermilk preparation) given to infants. Scores for comparability ranged from zero to four stars with only two studies achieving the full four stars. Of the studies not awarded full marks, none had adjusted for socioeconomic status in the analysis, despite data on socioeconomic status being collected during the study in some cases.23, 25, 26, 27 Gunnarsdottir and Thorsdottir19 and Hoppe et al.22 did not control for maternal education during analysis (Ong et al.23 controlled for maternal education and age but the results were unchanged). Kanoa et al.26 presented the frequency of overweight in children introduced to various complementary food groups, or to children less than or more than 6 months of age without controlling for any other variables. We carried out further analysis of these figures to determine if overweight was more likely in those children exposed to each food after 6 months or before 6 months (Table 4).

Four of the studies gained the maximum of three stars for quality of assessment. Of the remaining studies, three did not report any details of subjects lost to follow-up,20, 21, 22 whereas Robinson et al.25 showed significant differences between the parents of those children who did not have dual X-ray absorptiometry as part of their follow-up examination (mothers were older, taller, achieved a higher level of educational attainment, breastfed for longer and were less likely to smoke in late pregnancy) and those that did. Of the three cross-sectional studies, two were awarded a star for 100% follow-up of the cohort automatically.26, 29

Main results

Macronutrient intake

Four of the ten studies looked at the impact of childhood macronutrient or energy intake and its effect on childhood BMI or %BF. After adjustment for confounding variables, two studies found that there was no significant effect of high total protein intake at 6, 9 or 12 months on childhood BMI or %BF,20, 22 although in one study, higher protein intake at 12 months was associated with a higher %BF before adjustment for age, sex, energy intake and baseline anthropometrics.20 Gunther et al.21 investigated the effect of different types of protein (total, animal, dairy, meat or cereal protein) and found that infants in the highest tertiles of animal protein intake (as % total energy intake) at 12 months had a higher %BF, whereas those in the highest tertiles of total, animal or dairy protein at the age of 12 months had a higher BMI z-score. Likewise, Gunnarsdottir and Thorsdottir19 found that protein intake (as % total energy intake) consumed by boys at 2, 4, 9 and 12 months was positively associated with BMI at the age of 6 years, although no effect was observed in girls. Ong et al.23 found that amongst formula or mixed-fed (but not breast-fed) infants, each 420 kj per day increase in energy intake at 4 months old led to a 25% increase in the risk of being overweight or obese at 5 years old.23

Food type/group

Four studies looked at the effect of different food type/group given during the complementary feeding period. Kanoa et al.26 found no association between the time at which seven different food groups were introduced during the weaning period and overweight at five years of age,26 whereas Schack-Nielsen et al.28 found that only firm foods (bread and biscuits mixed with milk) had an inverse association with BMI z-scores at both 10 and 11 years of age, after adjusting for confounding variables. Before adjustment, the age at introduction of gruel (due to the time elapsed since data were collected, the authors were not able to supply a definition of gruel) was inversely associated with BMI z-score at 7–11 years of age. Santos et al.27 found no association between the use of milk thickeners (corn, rice or cassava flour added to cow’s milk) during infancy and weight-for-age or weight-for-height at 4 years of age, although increases in weight-for-age and length-for-age z-scores were observed when the infants were 12 months old. Simon et al.29 found no association between any of a list of 19 different foods/food groups given during infancy and childhood BMI.

Adherence to dietary guidelines

The only study to examine the link between the adherence to dietary guidelines during the complementary feeding period used principle components analyses to identify dietary patterns and create an Infant Guideline Score (IGS). No association was found between IGS and either BMI, fat mass or fat-mass index, but there was a positive association between increasing infant guideline score, and both lean mass and lean mass index amongst 4 year old children.25

Breastfeeding

Gunnarsdottir and Thorsdottir,19 both papers by Gunther et al.20, 21 and Ong et al.23 included breast and formula milk in their dietary analysis, either by weighing infants (breast milk) or by weighing the bottle (formula milk), before and after feeding. Gunarsdottir and Thorsdottir19 and Gunther et al.20 found lower intakes of protein in those babies that were breast-fed rather than formula-fed, whereas Ong et al.23 found lower intake of energy amongst breast-fed compared to mixed-fed or formula-fed infants. Owing to the different methods of estimating intake in breast- and in formula-fed infants, however, Ong et al.23 treated the two feeding methods separately in their analysis. Gunnarsdottir and Thorsdottir,19 Simon et al.29 and Schack-Nielsen et al.28 found an inverse association between breastfeeding duration and childhood BMI (Gunnarsdottir and Thorsdottir19 only found an association in boys). Robinson et al.25 found that children who were breastfed for longer had a lower fat mass and fat-mass index at the age of 4 years, whereas those families who were more likely to follow dietary guidelines also breastfed for longer. Santos et al.,27 Hoppe et al.22 and Kanoa et al.26 did not adjust for or include breastfeeding at all in their analysis.

Discussion

Macronutrient intake

With respect to protein intake, the data from the studies included in this review were inconclusive. Gunther et al.20 looked at protein intake (as % energy) at discrete time points and found that only high intakes at 12 months were positively associated with a higher BMI z-score at 7 years of age. This turned out to be non-significant, however, when adjusted for confounding variables such as age, sex and baseline anthropometrics. High intakes at 12 months, coupled with high protein intakes throughout the second year were also associated with a higher BMI z-score at 7 years of age but, within the scope of the present review, intakes beyond 12 months were considered to be beyond the complementary feeding period. The study by Hoppe et al. 22 showed no association between protein intake at 9 months with either BMI or %BF (measured by dual X-ray absorptiometry) at 10 years. Both Gunnarsdottir and Thorsdottir19 and a second paper by Gunther et al.21 showed that those in the very highest quartiles/tertiles of protein intake (as % energy) at 2, 4, 9 and 12 months had a higher BMI z-score at 6 and 7 years of age ,respectively, than those in lower quartiles/tertiles (total energy intakes were not different between the quartiles/tertiles) but the lack of a linear relationship could mean that it is only those with very high intakes, who are effected. Gunnarsdottir and Thorsdottir19 also only found an association in boys. Interestingly, none of the four papers found any association between protein intake at 6 months of age and childhood BMI or %BF, supporting our view that the introduction of high protein complementary foods is not related to later adiposity. A survey carried out in the UK found that 50% of infants were weaned before 23 weeks of age.31 If this is true, and the majority of infants are regularly consuming complementary foods by 6 months (with potentially a high, medium or low intake of protein), then the macronutrient content of the food infants eat during the complementary feeding period (from 6–12 months of age) may be of less importance than the type of milk feeding in early infancy or the family diet eaten at 12 months and over. From the studies included in the review, intakes of protein at 12 months and beyond appear to be the best predictor of obesity in childhood.

The second study by Gunther et al.21 studied the type of protein that infants consumed, and found that a positive association with BMI is more likely with higher intakes (% energy) of total protein (including all animal and vegetable sources of protein and human breast milk), animal protein (including meat and dairy proteins but not human breast milk) and dairy protein (cow milk, cow-milk-based infant formula milk, custard, cheese, yoghurt and so on). The inclusion of formula milk under dairy protein would make formula-fed babies those with the highest intakes of animal and dairy protein and, therefore, those with the highest BMI at 7 years, but this is not clear. The study adjusted for breastfeeding characteristics but no further details are provided. Assuming that the complementary feeding period spans 6–12 months, then it is also unclear if it is protein intake during the complementary feeding period or the typical family diet (consumed from around 12 months), where a higher intake of protein becomes associated with BMI and body fatness in childhood.

Ong et al.23 was the only study to focus on energy intake and found a linear association between energy intake at 4 months and the risk of a higher BMI in childhood (at 1, 2, 3 and 5 years of age), but in formula- or mixed-fed infants only. The study also showed that rapid weight gain was positively associated with higher energy intake at 4 months and independently predicted obesity risk in children, a finding shared by Gunnarsdottir and Thorsdottir.19, 23 Total energy intake was higher in those formula- or mixed-fed infants who were weaned earlier (at 1–2 months) than those weaned at 4 months. Formula-fed infants may, therefore, be less able to self-regulate energy intake, or early weaning could displace milk from the diet and lead to higher energy and protein intakes from complementary food in early infancy.23 No breakdown of the contribution of breast/formula milk and complementary foods to energy intake was described to support this hypothesis. No data showed any association of carbohydrate or fat intake on childhood BMI or adiposity.19

Food type/group

The review identified four papers that looked at food type/group given during the complementary feeding period and subsequent BMI or adiposity in childhood. No association was found between the types of food given and the outcome of interest except in the paper by Schack-Neilsen et al.,28 where the earlier introduction of some foods was inversely associated with BMI z-scores in childhood and later introduction of specific complementary foods was associated with a lower adult BMI and a 6–10% lower risk of overweight per 1 month delay. These findings, however, relate to the timing of introduction of specific foods rather than whether or not they were given, and were considered beyond the scope of this review. A second review by the authors has considered the impact of the timing of the introduction of complementary foods.14 As in the paper by Ong et al.,23 Schack-Neilsen et al.28 hypothesised that earlier introduction of complementary foods, rather than the types of food given, leads to higher energy intakes from an earlier age. Breast milk, which is low in protein, may be displaced by complementary foods higher in energy and protein, but no data on energy or nutrient intake were presented. Santos et al.27 found that babies of low birth weight were more likely to have milk thickeners (corn, rice or cassava flour added to full-fat cow’s milk) added to their bottle than children with a normal birth weight, and that the children who had consumed milk thickeners had greater weight, length and greater weight-for-age and length-for-age z-scores at 12 months of age, but these differences did not persist into later childhood. The use of thickeners may, therefore, promote rapid growth during the first year, but there was no evidence from this study that this leads to overweight or obesity in childhood. Data on the amount of cow’s milk consumed instead of/in addition to breastfeeding, the composition of the milk thickeners or the use of sugar in addition to milk thickeners were not available from the retrospective infant-feeding questionnaire. Simon et al.29 found that the introduction of children to sugar at 12 months of age or older was a risk factor for childhood obesity amongst exclusively breast-fed children only, suggesting that the family diet may be more influential than the weaning diet.

Adherence to dietary guidelines

Robinson et al.25 found that infants fed a diet based on fruit, vegetables, meat, fish and home-prepared foods (such as rice and pasta) had a higher lean mass at 4 years of age, but there was no association with either fat mass or BMI.25 The study was well-conducted and scored highly in the quality assessment. The parents of children who took part in the study tended to be educated to a higher level, breastfed for longer and were less likely to smoke than other members of the cohort, but only education and smoking were controlled for in the analysis. The authors were not clear as to the mechanism by which the weaning diet is linked to a greater lean mass in childhood, but suggested that children following weaning guidelines are more likely to continue to eat a diet that follows dietary guidelines in childhood, allowing ‘a greater growth in lean mass’.25 This has been shown to be the case in another study using data from the Southampton Women’s Survey and from participants in the ALSPAC study.32, 33 This also suggests that the weaning diet may be indicative of the family diet, but it is the family diet which may be of greater importance in terms of long-term health outcomes for children.

Breastfeeding

The type of milk feeding (breast milk, formula milk or mixed feeding) appears to be independently associated with complementary feeding, and breastfeeding may have a protective effect against overweight and obesity, although this was not the case in all the studies. Breast-fed infants had lower intakes of energy and protein in infancy, were introduced to solid foods later and had parents more likely to follow infant-feeding guidelines, and were possibly more likely to follow food-based dietary guidelines in early childhood, resulting in children more likely to eat a healthy balanced diet and with a reduced likelihood over overweight or obesity. Ever breastfeeding and a longer duration of breastfeeding may be a characteristic of those families more likely to follow Government guidelines for infant feeding and a healthy family diet should be adjusted for in the analysis of studies of this type.

Conclusions

To conclude, this review found some evidence that a high energy intake in very early infancy may lead to higher BMI and %BF during childhood,23 but this was the finding of a single study and should be regarded as inconclusive. Rapid growth has been shown to predict childhood obesity in two studies19, 23 but not in a third.29 There is limited evidence on the extent to which protein intake at 4–12 months is important, although consistently high protein intake (as % food energy) throughout infancy and into the second year of life may increase BMI, a finding similar to that of another recent review.20, 34 A high intake of protein (% energy) at 12 months of age and a high intake of animal and dairy protein (% energy) at 12 months, may also lead to higher BMI and %BF during childhood.20, 21 In other studies by Hoppe et al.,35, 36 high protein intakes from skimmed milk have been shown to raise insulin-like growth factor-1and insulin secretions, the mechanism by which it is thought that adipocyte synthesis is promoted. This may explain the higher incidence of obesity in formula-fed infants, compared to breast-fed infants, and in babies who consume more dairy products and/or formula milk during the complementary feeding period. Breastfeeding is independently associated with complementary feeding and in developed countries, is likely to be a characteristic of families with healthier lifestyles. Larger studies involving more participants may help to reduce the ambiguity of the literature.

The introduction of particular food type/group has no impact on BMI, but adherence to (UK) dietary guidelines during infancy may represent a greater likelihood of a healthy family diet, which in turn leads to increased lean mass. This highlights the need for a healthy balanced diet throughout childhood, rather than a focus on specific foods given during the complementary feeding period. The results of this review highlight the need for more studies that look at lean and fat mass instead of, or in addition to, BMI.

References

World Health Organzation. World Health Report: Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life. Geneva 2002.

International Association for the Study of Obesity. London (2012), available at http://www.iaso.org/site_media/library/resource_images/Childhood_overweight_and_obesity_by_Region.pdf (accessed Aug 2012).

Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ . Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev 2008; 9: 474–488.

Swinburn B, Shelly A . Effects of TV time and other sedentary pursuits. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008; 32 (Suppl 7): S132–S136.

Hills AP, Andersen LB, Byrne NM . Physical activity and obesity in children. Br J Sports Med 2011; 45: 866–870.

Guran T, Bereket A . International epidemic of childhood obesity and television viewing. Minerva Pediatr 2011; 63: 483–490.

Keane E, Layte R, Harrington J, Kearney PM, Perry IJ . Measured parental weight status and familial socio-economic status correlates with childhood overweight and obesity at age 9. PLoS One 2012; 7: e43503.

Kendzor DE, Caughy MO, Owen MT . Family income trajectory during childhood is associated with adiposity in adolescence: a latent class growth analysis. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 611.

Gregori D, Foltran F, Ghidina M, Zobec F, Berchialla P . Familial environment in high- and middle-low-income municipalities: a survey in Italy to understand the distribution of potentially obesogenic factors. Public Health 2012; 126: 731–739.

Fiese BH, Hammons A, Grigsby-Toussaint D . Family mealtimes: a contextual approach to understanding childhood obesity. Econ Hum Biol 2012; 10: 365–374.

Beyerlein A, von Kries R . Breastfeeding and body composition in children: will there ever be conclusive empirical evidence for a protective effect against overweight? Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 94 (Suppl 6): 1772S–1775S.

WHO. Report of the Expert Consultation of the Optimal Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding. WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

Department of Health. In NHS (ed). Weaning: Starting Solid Food. UK: Department of Health, 2008.

Pearce J, Langley-Evans SC . Timing of complementary food introduction and the risk of childhood obesity: a systematic review. Int J Obes (Paper submitted).

Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data 2000; 1–27.

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH . Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. Br Med J 2000; 320: 1240–1243.

Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2000; 894, i-xii 1–253.

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. In 2011.

Gunnarsdottir I, Thorsdottir I . Relationship between growth and feeding in infancy and body mass index at the age of 6 years. Int J Obes 2003; 27: 1523–1527.

Gunther AL, Buyken AE, Kroke A . Protein intake during the period of complementary feeding and early childhood and the association with body mass index and percentage body fat at 7 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr 2007; 85: 1626–1633.

Gunther ALB, Remer T, Kroke A, Buyken AE . Early protein intake and later obesity risk: which protein sources at which time points throughout infancy and childhood are important for body mass index and body fat percentage at 7 y of age? Am J Clin Nutr 2007; 86: 1765–1772.

Hoppe C, Molgaard C, Thomsen BL, Juul A, Michaelsen KF . Protein intake at 9 mo of age is associated with body size but not with body fat in 10-y-old Danish children. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 79: 494–501.

Ong KK, Emmett PM, Noble S, Ness A, Dunger DB, Team AS . Dietary energy intake at the age of 4 months predicts postnatal weight gain and childhood body mass index. Pediatrics 2006; 117: E503–E508.

Mills A . Food Standards Agency: Food Portion Sizes. TSO: London, 2002.

Robinson SM, Marriott LD, Crozier SR, Harvey NC, Gale CR, Inskip HM et al. Variations in infant feeding practice are associated with body composition in childhood: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94: 2799–2805.

Kanoa BJ, Zabut BM, Harried AT . Nutritional status compared with nutritional history of preschool aged children in gaza strip: cross sectional study. Pakistan J Nutr 2011; 10: 282–290.

Santos IS, Matijasevich A, Valle NCJ, Gigante DP, de Moura DR . Milk thickeners do not influence anthropometric indices in childhood. Food Nuts Bull 2006; 27: 245–251.

Schack-Nielsen L, Sørensen TIA, Mortensen EL, Michaelsen KF . Late introduction of complementary feeding, rather than duration of breastfeeding, may protect against adult overweight. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 91: 619–627.

Simon VGN, de Souza JMP, de Souza SB . Breastfeeding, complementary feeding, overweight and obesity in pre-school children. Rev Saude Publica 2009; 43: 60–69.

WHO. A Growth Chart for International Use in Maternal and Child Health Care: Guidelines for Primary Health Care Personnel Geneva: WHO; London: HMSO: 1978.

Moore AP, Milligan P, Goff LM . An online survey of knowledge of the weaning guidelines, advice from health visitors and other factors that influence weaning timing in UK mothers. Matern Child Nutr 2012. e-pub ahead of print 19 June 2012; doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00424.x.

Robinson S, Marriott L, Poole J, Crozier S, Borland S, Lawrence W et al. Dietary patterns in infancy: the importance of maternal and family influences on feeding practice. Br J Nutr 2007; 98: 1029–1037.

Northstone K, Emmett P . Multivariate analysis of diet in children at four and seven years of age and associations with socio-demographic characteristics. Eur J Clin Nutr 2005; 59: 751–760.

Michaelsen KF, Larnkjaer A, Molgaard C . Amount and quality of dietary proteins during the first two years of life in relation to NCD risk in adulthood. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2012; 22: 781–786.

Hoppe C, Molgaard C, Juul A, Michaelsen KF . High intakes of skimmed milk, but not meat, increase serum IGF-I and IGFBP-3 in eight-year-old boys. Eur J Clin Nutr 2004; 58: 1211–1216.

Hoppe C, Udam TR, Lauritzen L, Molgaard C, Juul A, Michaelsen KF . Animal protein intake, serum insulin-like growth factor I, and growth in healthy 2.5-y-old Danish children. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 80: 447–452.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Sarah McMullen for her advice and expertise during the review process and writing of the paper.This work was funded by a grant from the Feeding for Life Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pearce, J., Langley-Evans, S. The types of food introduced during complementary feeding and risk of childhood obesity: a systematic review. Int J Obes 37, 477–485 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Differences in infant feeding practices between Indian-born mothers and Australian-born mothers living in Australia: a cross-sectional study

BMC Public Health (2022)

-

A core outcome set for trials of infant-feeding interventions to prevent childhood obesity

International Journal of Obesity (2020)

-

Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of pediatric obesity: consensus position statement of the Italian Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetology and the Italian Society of Pediatrics

Italian Journal of Pediatrics (2018)

-

Family meals with young children: an online study of family mealtime characteristics, among Australian families with children aged six months to six years

BMC Public Health (2017)

-

Diet diversity, growth and adiposity in healthy breastfed infants fed homemade complementary foods

International Journal of Obesity (2017)