Abstract

Studies of electronic interferometers, based on edge-channel transport in the quantum Hall effect regime, have been stimulated by the search for evidence of abelian and non-abelian anyonic statistics of fractional charges. In particular, the electronic Fabry–Pérot interferometer has been found to be Coulomb dominated, thus masking coherent Aharonov–Bohm interference patterns: the flux trapped within the interferometer remains unchanged as the applied magnetic field is varied, barring unobservable modulations of the interference area. Here we report on conductance measurements indicative of the interferometer’s area ‘breathing’ with the variation of the magnetic field, associated with observable (a fraction of a flux quantum) variations of the trapped flux. This is the result of partial (controlled) screening of Coulomb interactions. Our results introduce a novel experimental tool for probing anyonic statistics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The behaviour of electrons and quasi-particles in mesoscopic systems stems from the combination of their wave-nature, particle-nature and the effect of Coulomb interactions. Electronic Fabry–Pérot interferometers (FPIs), and more generally ring-like geometries, have been utilized for the investigation of all these three facets1,2,3,4 and the rich interplay among them5,6,7,8,9,10. In particular, electronic FPIs have possibly been the most studied candidates for probing belian and non-abelian anyonic statistics of quasi-particles in the fractional quantum Hall effect (FQHE) regime11,12,13,14. Notwithstanding considerable efforts, the experimental study of anyonic statistics is still lagging behind theory, mostly owing to the adverse effect of Coulomb interactions. Two distinct regimes in the operation of FPIs—characterized by the conductance oscillation frequencies with the applied flux—have been reported7,8 and studied theoretically15,16,17,18,19. In the coherent AB regime, one period of these oscillations corresponds to the increase of the threaded flux through the interferometer’s area by a single flux quantum φ0=h/e (e—electron charge and h—Planck’s constant)20. On the other hand, in the Coulomb-dominated (CD) regime, it is the mutual capacitance between the device and a modulation gate that dictates the oscillation periodicities. Interference in the AB regime is harder to observe7,8, and has not been achieved thus far in any fractional quantum Hall state. At the same time, the CD regime has its own disadvantage—it does not and cannot reveal the anyonic statistics.

The AB phase underlying interference patterns evolves as 2πδφAB/φ0=2π(AδB+BδA0)/φ0, where δφAB is the variation of the threaded flux through the FPI, B the applied magnetic field, A the area enclosed by the interfering edge channel and δA0=α˙δVMG is the area variations due to the modulation gate (but excluding the effect of Coulomb interaction as explained below). Here α is the edge-channel modulation-gate mutual capacitance. The AB oscillations with δB and δVMG are hence characterized by the following frequencies:

By contrast, in the CD regime with the outer most edge channel interfering, there is no B dependence of the conductance,

Here, 1/γ is the voltage required to remove a single electron from the FPI3,4,5,6, which does not depend upon the magnetic field (in similitude to the single-electron transistor21).

Seemingly, these two regimes may seem to be of very different nature: while the AB oscillations are due to coherent interference, the CD oscillations reflect solely the electron occupancy of the device and do not contain any information regarding the phase acquired by the interfering particles. This interpretation turned out to be too naive. A unified theoretical framework has suggested that the CD oscillations may, in fact, be AB oscillations modified by Coulomb interaction15. According to this interpretation7,8,15, as the magnetic field increases (decreases) so that the AB phase varies by AδB, the area will shrink (inflate) by δAint to keep a constant flux AδB+BδAint=0, where the subscript ‘int’ stands for ‘interactions’. This variation of the area guarantees that the charge enclosed in the interfering area is kept constant, minimizing the charging energy of the device. Then, once the flux variation reaches the value of a whole flux quantum, AδB=φ0, an electron abruptly ‘jumps’ from the bulk into the edge and the original area is restored7,15.

According to this description, the area enclosed by the outer edge channel is ‘breathing’; on increasing the magnetic field it continuously shrinks and then abruptly inflates, altogether with periodicity ΔB=φ0/A. Nonetheless, the breathing in the CD regime has never been experimentally confirmed. The reason is that the measured conductance is simply constant, as the magnetic field is varied. Basically, the area response to increasing the magnetic field fully compensates the effect of the latter. The subsequent abrupt addition of an electron leads to a 2π jump in the interference phase—clearly an unobservable effect as well. We are thus ‘blind’ to this phenomenon of area breathing.

Here we report on the realization of a novel device that combines the advantages of AB interferometers with CD response. It operates in an intermediate regime—in which the area response does not fully compensate the variations of the magnetic field, rendering the area ‘breathing’ observable. In other words,  , with 0<ξ<1, leading to a total phase evolution

, with 0<ξ<1, leading to a total phase evolution  . Our main findings concerning this ‘breathing’ are summarized in equations (8, 9, 10) below. Measurements were performed on three different devices showing three distinct behaviours: AB dominated, namely, ξ=0 with no area breathing; CD, namely, ξ=1 with invisible breathing of the area; and an intermediate one (ξ=0.75), with clear area breathing. We present conductance measurements of this novel device that incorporates both AB and CD frequencies (equations (1, 2, 3, 4)), hence contain information regarding both interference and interactions, and the interplay between them. Moreover, employing detailed analysis based on the system’s energy, we deduce the device’s charge stability diagram, providing an insight to its rich physics being ‘hidden’ in the previously reported AB and CD devices. Furthermore, we provide proposals for utilizing our device for probing anyonic statistics of quasi-particles in the FQHE regime.

. Our main findings concerning this ‘breathing’ are summarized in equations (8, 9, 10) below. Measurements were performed on three different devices showing three distinct behaviours: AB dominated, namely, ξ=0 with no area breathing; CD, namely, ξ=1 with invisible breathing of the area; and an intermediate one (ξ=0.75), with clear area breathing. We present conductance measurements of this novel device that incorporates both AB and CD frequencies (equations (1, 2, 3, 4)), hence contain information regarding both interference and interactions, and the interplay between them. Moreover, employing detailed analysis based on the system’s energy, we deduce the device’s charge stability diagram, providing an insight to its rich physics being ‘hidden’ in the previously reported AB and CD devices. Furthermore, we provide proposals for utilizing our device for probing anyonic statistics of quasi-particles in the FQHE regime.

Results

Experimental set-up

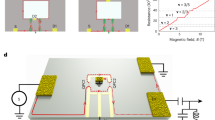

The devices were fabricated on a GaAs-AlGaAs heterostructure, embedding a two-dimensional (2D) electron gas with electron density ∼2 × 1011 cm−2. Electron-beam and optical lithography were employed in the fabrication process, and measurements were performed at electron temperature ∼30 mK. All FPIs consist of a pair of quantum point contacts (QPCs), playing the role of semi-transparent mirrors (Fig. 1). Three different types of devices are shown in Fig. 1. In Fig. 1a, we show the simplest realization of a FPI; such FPIs have high charging energy, regardless of their size7,8,22, thus showing CD behaviour. Tto suppress Coulomb interactions, a small Ohmic contact (106 nm Au/53 nm Ge/40 nm Ni with surface area 0.5 μm2 alloyed to the heterostructure) is placed at the centre of the interferometer’s bulk22 (Fig. 1b, gold, false colour; see Methods for more information regarding the Ohmic contact). Such devices show AB behaviour22. A third type of device, not reported previously (to the best of our knowledge), consists of placing such Ohmic contacts in the vicinity of the FPI, as depicted in Fig. 1c. Unexpectedly, we have found that in such a device, the suppression of the Coulomb interactions is less efficient than the centre Ohmic contact, yet it is still significant, giving rise to a new regime intermediate between AB and CD. The role of this Ohmic contact placed in the device’s vicinity is to screen the Coulomb interactions via its capacitance to the interferometer’s bulk (increasing Cbulk while maintain Ceb intact, see definitions in Discussion below and more details in Methods), effectively lowering the device’s charging energy and decreasing the interaction parameter ξ. All three devices were fabricated on the same heterostructure and designed to have the same size A≈2.5 μm2 so that they differ merely by the presence and the position of the Ohmic contacts. A fourth type of device, with the Ohmic contact inside its bulk, and surrounded by an additional gate was found to operate in the intermediate regime as well, and is discussed in Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Figs 1–3. All measurements were conducted at bulk fillings 1<νB<2, with the outer most edge-channel interfering.

(a) Bare FPI; such devices show distinct Coulomb dominated (CD) behaviour. (b) FPI with a grounded Ohmic contact in its centre (gold, false colour) aimed at screening Coulomb interactions; such devices show Aharonov–Bohm (AB) interference. (c) FPI with a grounded Ohmic contact in its close proximity (gold, false colour), inducing partial screening of Coulomb interactions; such devices show intermediate behaviour between the CD and AB. Red lines represent edge states and arrows represent the current’s chirality. Current is injected into the device from the source, partitioned at the two QPCs, and probed at the drain employing a cold amplifier. Partitioned current is denoted by dashed lines. Modulation gates are marked by blue (false colour) in all images. (d) An equivalent electric circuit model describing the interferometer system with filling factor 1<vB<2. The system consists of the lowest Landau level’s edge (denoted as ‘edge’), the bulk (denoted as ‘bulk’) and the modulation gate. The mutual capacitances between all three, Ceb, Cedge and Cbulk, are marked on top of the circuit. The excess charge on the edge is denoted δQedge=δq3−δq1, while the excess charge in the bulk is  . Further details on the capacitive model are provided in analysis, as well as in Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 5.

. Further details on the capacitive model are provided in analysis, as well as in Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 5.

Observations

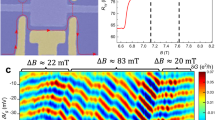

Tuning the magnetic field to the νB=2 plateau and partitioning the outer edge channel, conductance oscillations are measured as function of δB and δVMG, with the different FPIs shown in Fig. 1. For the device shown in Fig. 1b, constant-phase lines in the B-VMG 2D plane follow a negative slope—a typical result in the AB regime (Fig. 2a). A fast Fourier transform (FFT) extracts  —agreeing well with the lithographically enclosed area, and

—agreeing well with the lithographically enclosed area, and  —needed to remove one flux quantum from the interior of the device (equations (1 and 2)). For the device shown in Fig. 1a, no oscillation as function of δB is observed—in agreement with the prediction for the CD regime (equations (3 and 4))—with a modulation-gate frequency

—needed to remove one flux quantum from the interior of the device (equations (1 and 2)). For the device shown in Fig. 1a, no oscillation as function of δB is observed—in agreement with the prediction for the CD regime (equations (3 and 4))—with a modulation-gate frequency  —needed to remove one electron.

—needed to remove one electron.

(a) 2D conductance measured with the FPI with an Ohmic contact in its centre (seen in Fig. 1b) at B=4.7 T. This plot shows a clear AB behaviour: constant-phase lines are marked with grey lines and the AB periods  and ΔB(AB) are marked accordingly. (b) 2D conductance measured with the bare FPI (seen in Fig. 1a) at B=4.7 T. This plot shows a clear CD behaviour with no dependence of the conductance on magnetic field; constant-phase lines are marked with grey lines and the CD period

and ΔB(AB) are marked accordingly. (b) 2D conductance measured with the bare FPI (seen in Fig. 1a) at B=4.7 T. This plot shows a clear CD behaviour with no dependence of the conductance on magnetic field; constant-phase lines are marked with grey lines and the CD period  is marked accordingly.

is marked accordingly.

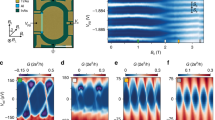

Turning to employing the device in Fig. 1c, we commenced by measuring the conductance for rather pinched QPCs (<t>=0.05), shown in Fig. 3a. This lattice-like conductance plot represents the charge stability diagram of the device and contains information both on the interference and on the device’s charging, as we elaborate in Discussion. Although this plot is rather complex, its 2D FFT, shown in Fig. 3b, is simple; it reveals a lattice of peaks (as expected from an FFT of a lattice) all being linear combinations of underlying AB and CD frequencies, denoted on top of the figure. We find  and

and  for the AB frequencies, and 1/ΔB(CD)=0 and

for the AB frequencies, and 1/ΔB(CD)=0 and  for the CD frequencies. These frequencies are found relatively close to the ones of the ‘pure AB’ and ‘pure CD’ cases extracted from Fig. 2a,b, respectively. Furthermore, we find

for the CD frequencies. These frequencies are found relatively close to the ones of the ‘pure AB’ and ‘pure CD’ cases extracted from Fig. 2a,b, respectively. Furthermore, we find  to be the only frequency that depends on magnetic field (in the tesla range), as anticipated from equations (1, 2, 3, 4) (Supplementary Fig. 4).

to be the only frequency that depends on magnetic field (in the tesla range), as anticipated from equations (1, 2, 3, 4) (Supplementary Fig. 4).

(a) 2D conductance measured with the FPI with an Ohmic contact in its vicinity (seen in Fig. 1c) at B=5 T, giving rise to a charge stability diagram. The vectors marked on top of the figure connect different cell and can be translated to physical processes, as elaborated in analysis. Grey lines mark the underlying AB and CD frequencies. (b) 2D FFT of the conductance in a, revealing a clear lattice structure as well, as expected from an FFT of a lattice. The underlying AB and CD frequencies, marked by two vectors (b1 and b2. respectively, highlighted with white dashed circles), span this Fourier lattice, and the reason for their appearance here is elaborated in analysis.

Moreover, by further opening the confining QPCs to <t>=0.7, the presence of abrupt jumps in the conductance (phase jumps) becomes more clear (Fig. 4a), which shows good agreement with the conductance’s model that stems from the minimization of the system’s energy (Fig. 4b; see Discussion below; Supplementary Notes 2–3; Supplementary Fig. 5–9).

(a) Conductance is measured with the same device as Fig. 3, but with substantially higher transmission (<t>≈0.7). Phase jump lines are marked by solid descending lines and the frequency defined by their slope is marked by  and ΔB(PJ). In between adjacent phase jump lines, we have continuous conductance oscillations. By extrapolating these continuous oscillations (dashed ascending lines), we may attribute them periodicities denoted

and ΔB(PJ). In between adjacent phase jump lines, we have continuous conductance oscillations. By extrapolating these continuous oscillations (dashed ascending lines), we may attribute them periodicities denoted  and ΔB(m). More details are provided in analysis. (b) Theoretical plot, simulated according to the conductance G expressed in Discussion. (c) Constant δVMG line taken from a, showing clear phase accumulation followed by abrupt phase jump of

and ΔB(m). More details are provided in analysis. (b) Theoretical plot, simulated according to the conductance G expressed in Discussion. (c) Constant δVMG line taken from a, showing clear phase accumulation followed by abrupt phase jump of  , which is also equal to the value of ξ (equation (11)). (d) The area response δAint inferred from the conductance’ phase (c). The relation between the area response and the phase is obtained by inverting the relation between δAint and the conductance G, provided in the caption of Fig. 5. Note that indeed (c,d) are highly similar (as anticipated by the theoretical plots, cf. yellow curves in Fig. 5d,b), but they are not identical. Naturally, for small values of the phase, the conductance is nearly proportional to it.

, which is also equal to the value of ξ (equation (11)). (d) The area response δAint inferred from the conductance’ phase (c). The relation between the area response and the phase is obtained by inverting the relation between δAint and the conductance G, provided in the caption of Fig. 5. Note that indeed (c,d) are highly similar (as anticipated by the theoretical plots, cf. yellow curves in Fig. 5d,b), but they are not identical. Naturally, for small values of the phase, the conductance is nearly proportional to it.

Analysis

Since the AB and CD types of behaviour are merely two different regimes of operation of the same device, they may be analysed within the same theoretical framework15. We address a set-up, where transport through the outer most edge channel at 1<νB<2 gives rise to interference. This case has been studied experimentally. We denote the charge added to the lowest Landau level (lowest LL) by Q↓ , and that added to the upper Landau level (upper LL) by δQ↑. Hereafter, we refer to the interfering outer most edge channel (compressible ring belonging to the lowest LL) as the ‘edge’, and to the rest of the charge inside the FPI as ‘bulk’23. The charge variations in the edge and bulk are denoted δQedge and δQbulk, respectively. We note that for any device without an Ohmic contact within its centre, δQ↑ changes discretely accounting for the localized charges in the bulk15,16.

We consider a minimal capacitive model for describing the FPI set-up15,16,24 depicted in Fig. 1d. The model consists of three capacitances Cedge, Cbulk and Ceb describing the mutual Coulomb interactions between the system’s three components, δQedge, δQbulk and δVMG. The total energy of the system can then be written as the sum of three contributions15,17,25,26, Etotal=Eeb+Eedge+Ebulk, where the second and third terms are the edge and bulk charging energies (depending solely on δQedge and δQbulk, respectively), and the first term is due to the interaction between them. This first term can be presented as function of their sum δQedge+δQbulk. The relation between this approach and an earlier one (cf. ref. 15), where the variable δQedge · δQbulk have been employed, is discussed in Supplementary Note 2. The system’s charge state is determined by minimizing the total energy Etotal.

In the quantum Hall regime, the charge added to the lowest LL, δQ↓, follows the total flux, δφtot, enclosed by the latter: as the flux increases (decreases), single-particle states cross in below (cross in above) the Fermi energy, increasing (decreasing) the number of occupied states:

Here, in the third term on the right hand side, δAint represents the interaction-induced area response. Thus, the overall variation of the area δA=δA0+δAint is separated into two components. The first component is a linear component that is solely a result of variations of the modulation-gate voltage, δA0=αBδVMG, and stems solely from its mutual capacitance to the interfering edge. The second component is an oscillating component7,15, δAint, which is a function of both δB and δVMG, for which we derive the full expression below (and allowing us to present the total phase as an explicit function of δB and δVMG, cf. equation (8) below).

Magnetic field variations

As the magnetic field increases and the filling factor decreases, charge is removed from the upper Landau level into the lowest Landau level. More precisely, with every flux quantum added, the degeneracy each Landau level increases by one; resulting in a transfer of a single electron from the upper LL (hence δQ↑=±1) to the lowest LL (hence δQ↓=±1), while keeping the total charge in the system constant. The corresponding variation of energy can be expressed in terms of δQ↑ and δQ↓15,27:

where δQtot=δQ↓+δQ↑,  ,

,  and all three coefficients are related to the relevant different capacitances15:

and all three coefficients are related to the relevant different capacitances15:  are system specific, with D=(Cedge+Ceb)(Cbulk+Ceb)−

are system specific, with D=(Cedge+Ceb)(Cbulk+Ceb)− .

.

Equation (6) implies that the energy is minimized if  and

and  , leading to δQtot=0 at all times. This continuous charging of the edge, δQ↓, should result in the periodicity ΔB=φ0/A. The latter coincides with the behaviour in the AB regime, as seen in Fig. 2a, measured with the device shown in Fig. 1b. In this device, while δQ↓ is continuously charged from the leads, δQ↑ is discharged into the centre Ohmic contact.

, leading to δQtot=0 at all times. This continuous charging of the edge, δQ↓, should result in the periodicity ΔB=φ0/A. The latter coincides with the behaviour in the AB regime, as seen in Fig. 2a, measured with the device shown in Fig. 1b. In this device, while δQ↓ is continuously charged from the leads, δQ↑ is discharged into the centre Ohmic contact.

Previous measurements have also reported the observations of AB oscillations even without the centre Ohmic contact, but rather with a top gate covering the device7,8. In that case, the upper LL’s charge δQ↑ cannot vary continuously (as in the case with an Ohmic contact at the centre of the device), but rather discretely, because the upper LL is isolated by an incompressible strip15,23. Thus, as the magnetic field increases such that AδB<φ0, the lowest LL is continuously charged by  , leading to an increase of the total charge

, leading to an increase of the total charge  with δQ↑=0 due to the upper LL’s charge quantization. This of course will increase the charging energy (which favors δQtot=0; first term in equation (6)), which is possible since the top gate effectively decreases KEB (and thus Ceb), such that KEB<<KE (and Ceb<<Cbulk)7,8,15. Then, once a whole flux quantum is added AδB=φ0, the energy can again be minimized by discharging the upper LL abruptly δQ↑=−e. This AB behaviour is summarized in Fig. 5a–c (blue), leading to a conductance depicted in Fig. 5d (blue).

with δQ↑=0 due to the upper LL’s charge quantization. This of course will increase the charging energy (which favors δQtot=0; first term in equation (6)), which is possible since the top gate effectively decreases KEB (and thus Ceb), such that KEB<<KE (and Ceb<<Cbulk)7,8,15. Then, once a whole flux quantum is added AδB=φ0, the energy can again be minimized by discharging the upper LL abruptly δQ↑=−e. This AB behaviour is summarized in Fig. 5a–c (blue), leading to a conductance depicted in Fig. 5d (blue).

(a) Total charge in the system, δQtot=δQ↓+δQ↑. (b) The area response δAint. (c) The total flux δφtot, including both the externally varied phase AδB/φ0 and the response BδAint/φ0. (d) The resulting conductance for relatively open QPCs (t2=0.85), taking the straightforward form  (further details are provided in Supplementary Note 3). All four graphs (a–d) are plotted versus variations of the magnetic field. (e–h) Similar graphs as a–d, as a function of modulation-gate voltage δVMG. The plots are given for the simple case of νB=2. For simplicity, we plot e–h in the case Cbulk=Cedge at bulk filling factor νB=2, leading to a CD frequency that is twice of the AB frequency. The choice of these values does not change the qualitative picture, and we note that we find Cbulk=1.45˙Cedge in the experiment, deduced from the measured frequencies.

(further details are provided in Supplementary Note 3). All four graphs (a–d) are plotted versus variations of the magnetic field. (e–h) Similar graphs as a–d, as a function of modulation-gate voltage δVMG. The plots are given for the simple case of νB=2. For simplicity, we plot e–h in the case Cbulk=Cedge at bulk filling factor νB=2, leading to a CD frequency that is twice of the AB frequency. The choice of these values does not change the qualitative picture, and we note that we find Cbulk=1.45˙Cedge in the experiment, deduced from the measured frequencies.

On the other hand, as alluded above in the CD regime, the total charge must be constant  at all times due to the large charging energy KEB≫KE, thus Ceb≫Cbulk (in the absence of an Ohmic contact or top gate). As a result, when the applied magnetic field is increased, the area shrinks to prevent the enclosed flux from increasing. This means

at all times due to the large charging energy KEB≫KE, thus Ceb≫Cbulk (in the absence of an Ohmic contact or top gate). As a result, when the applied magnetic field is increased, the area shrinks to prevent the enclosed flux from increasing. This means  , with δQ↓=0 due to the bulk’s quantization, leading to δAint=−AδB/B. In that case, as the interferometer’s area shrinks, a dipole is created: a depleted region (positively charged) is created just outside the boundary of the shrinking interferometer, while an excess negative charge accumulates inside. The energy increase due to this dipole is reflected by the second and third terms in equation (6). Once a whole flux quantum is added AδB=φ0, the energy can again be minimized by abruptly moving an electron from the upper LL to the lowest LL, described by the simultaneous variation δQ↑=−e and δQ↓=+e. At this point, the area response δAint should abruptly vanish from ∼810 nm2 (a flux quantum’s area at 5 T) to 0 μm2. Such an abrupt response cannot be inferred from the measured conductance (Fig. 2b), since it should result in a 2π variation of the Aharonov–Bohm phase. This leaves the conductance constant as function of δB. This CD behaviour is summarized in Fig. 5a–c (purple), leading to a conductance depicted in Fig. 5d (purple).

, with δQ↓=0 due to the bulk’s quantization, leading to δAint=−AδB/B. In that case, as the interferometer’s area shrinks, a dipole is created: a depleted region (positively charged) is created just outside the boundary of the shrinking interferometer, while an excess negative charge accumulates inside. The energy increase due to this dipole is reflected by the second and third terms in equation (6). Once a whole flux quantum is added AδB=φ0, the energy can again be minimized by abruptly moving an electron from the upper LL to the lowest LL, described by the simultaneous variation δQ↑=−e and δQ↓=+e. At this point, the area response δAint should abruptly vanish from ∼810 nm2 (a flux quantum’s area at 5 T) to 0 μm2. Such an abrupt response cannot be inferred from the measured conductance (Fig. 2b), since it should result in a 2π variation of the Aharonov–Bohm phase. This leaves the conductance constant as function of δB. This CD behaviour is summarized in Fig. 5a–c (purple), leading to a conductance depicted in Fig. 5d (purple).

To summarize, for any device without an Ohmic contact within its centre (implying a quantization condition on δQ↑), the system ‘decides’ whether it shrinks or not, and by how much, according to the values of KEB and KE. Taking the derivative of the total energy with respect to δAint, we obtain δAint=−ξ·AδB/B, with  . The AB regime corresponds to the limit KE≫KEB, leading to ξ=0 and δAint=0; the CD corresponds to the limit KE<<KEB, leading to ξ=1 and δAint=−AδB/B. The behaviour in the intermediate regime is summarized in Fig. 5a–c (red and yellow for ξ=0.25 and ξ=0.75, respectively), resulting in the conductance depicted in Fig. 5d.

. The AB regime corresponds to the limit KE≫KEB, leading to ξ=0 and δAint=0; the CD corresponds to the limit KE<<KEB, leading to ξ=1 and δAint=−AδB/B. The behaviour in the intermediate regime is summarized in Fig. 5a–c (red and yellow for ξ=0.25 and ξ=0.75, respectively), resulting in the conductance depicted in Fig. 5d.

The theoretical prediction (ξ=0.75; Fig. 5d, yellow) is consistent with the measured conductance shown in Fig. 4c, from which we have retrieved both the area=2.6 μm2 (from the main periodicity) and the interaction parameter ξ=0.75 (from the amplitude of the phase jumps). The possibility to extract these two parameters from a single magnetic field scan demonstrates the versatile information contained in the intermediate regime—it incorporates both interactions (quantified by ξ) and interference (related to A). Furthermore, from the conductance (Fig. 4c), we infer the evolution of the area response, δAint, as function of δB, shown in Fig. 4d. We find a maximal area response of δAint=500 nm2, which is in good agreement with our expectation  .

.

Modulation-gate variations

The two handles we have, varying the magnetic field δB and varying the modulation-gate voltage δVMG, are substantially different from each other. While in both AB and CD regimes, the total charge must be conserved for δB variations on the scale of several flux quanta, AδB≫φ0, δVMG induces charge on the device through its capacitance γ: applying δVMG requires charging the device by δQtot=γδVMG that divides into each Landau levels15,16:  and

and  . Thus, the energy variation of the system (equation (6)) can be reformulated as:

. Thus, the energy variation of the system (equation (6)) can be reformulated as:

Although equation (7) is valid for any variation of δB and δVMG, only modulation-gate variations, δVMG, are considered in this section.

In the AB regime, as the modulation-gate voltage increases by δVMG such that  , the lowest LL is continuously charged by

, the lowest LL is continuously charged by  allowing us to observe Aharonov–Bohm interference with a period

allowing us to observe Aharonov–Bohm interference with a period  (cf. Fig. 2a). Note that α is independent to the magnetic field (Supplementary Fig. 4). Simultaneously, we expect the upper LL to be continuously charged from the centre Ohmic contact, satisfying

(cf. Fig. 2a). Note that α is independent to the magnetic field (Supplementary Fig. 4). Simultaneously, we expect the upper LL to be continuously charged from the centre Ohmic contact, satisfying  . Alternatively, with top-gated devices (KEB<<KE), the upper LL acquires an additional electron discretely only once this last expression (which can be regarded as the induced charge in the bulk) amounts to an increase by a whole-electron charge

. Alternatively, with top-gated devices (KEB<<KE), the upper LL acquires an additional electron discretely only once this last expression (which can be regarded as the induced charge in the bulk) amounts to an increase by a whole-electron charge  . This AB behaviour is summarized in Fig. 5e–g (blue) and results in a conductance depicted in Fig. 5h (blue).

. This AB behaviour is summarized in Fig. 5e–g (blue) and results in a conductance depicted in Fig. 5h (blue).

By contrast, in the CD regime, the high charging energy KEB<<KE requires  for all values of δVMG. As δQ↑=0 due to charge quantization in the upper LL, it follows that

for all values of δVMG. As δQ↑=0 due to charge quantization in the upper LL, it follows that  . According to equation (5), this necessitates an area response

. According to equation (5), this necessitates an area response  , (which is always larger than zero since

, (which is always larger than zero since  ; see Supplementary Figs 2 and 4). Namely, while in the AB regime the area dilations are dictated solely by the mutual capacitance between the edge and the modulation gate, α, here, in the CD regime, the area dilations overshoots to satisfy the capacitance of the device (including both the edge and the bulk) to the modulation gate, γ. This overshoot will cost an energy proportional to KE (equation (7)). Then again, once this overshoot is equivalent to a whole electron, the area will retract back minimizing the total energy. This CD behaviour is summarized in Fig. 5e–g (purple) and results in a conductance depicted in Fig. 5h (purple).

; see Supplementary Figs 2 and 4). Namely, while in the AB regime the area dilations are dictated solely by the mutual capacitance between the edge and the modulation gate, α, here, in the CD regime, the area dilations overshoots to satisfy the capacitance of the device (including both the edge and the bulk) to the modulation gate, γ. This overshoot will cost an energy proportional to KE (equation (7)). Then again, once this overshoot is equivalent to a whole electron, the area will retract back minimizing the total energy. This CD behaviour is summarized in Fig. 5e–g (purple) and results in a conductance depicted in Fig. 5h (purple).

Similarly to the analysis of magnetic field variations, we can express the area response to variations of δVMG for any value of the interaction parameter ξ: we obtain  resulting in a total area variation

resulting in a total area variation  . This is summarized in Fig. 5e–h (red and yellow for ξ=0.25 and ξ=0.75, respectively).

. This is summarized in Fig. 5e–h (red and yellow for ξ=0.25 and ξ=0.75, respectively).

Analysis of the entire B − VMG plane

So far, we have analysed the area response to variations of either δB or δVMG. We now turn our attention to concomitant variations of both. This will allow us to analyse the data shown in Figs 3a and 4a. Notably, the interference pattern in Figs 3a and 4a may be decomposed into two ingredients. First, descending lines along which phase jumps take place (cf. solid lines in Fig. 4a). The respective periodicities are denoted  and ΔB(PJ) (marked on top of Fig. 4a, with the superscript ‘PJ’ for ‘phase jump’). Second, continuous conductance oscillations with respect to modulation-gate voltage and magnetic field in between two adjacent phase jump lines. The corresponding periodicities are then

and ΔB(PJ) (marked on top of Fig. 4a, with the superscript ‘PJ’ for ‘phase jump’). Second, continuous conductance oscillations with respect to modulation-gate voltage and magnetic field in between two adjacent phase jump lines. The corresponding periodicities are then  and ΔB(m),respectively (marked on top of Fig. 4a as well, with the superscript ‘m’ for ‘modified’). These continuous oscillations reflect the interference of electrons at the edge. Crossing a maximal conductance line (for example, following arrow a2 in Fig. 3a) corresponds to an incremental variation of δQ↓ by ±e. Here, ‘modified’ alludes to the fact that these continuous oscillations are in fact coherent AB oscillations modified by the Coulomb interaction. Likewise, crossing a phase jump line (for example, following arrow a1 in Fig. 3a) implies a change of the upper LL’s charge δQ↑ by ±e. Naturally, the combination of these two types of processes gives rise to the system’s charge stability diagram in the B−VMG plane.

and ΔB(m),respectively (marked on top of Fig. 4a as well, with the superscript ‘m’ for ‘modified’). These continuous oscillations reflect the interference of electrons at the edge. Crossing a maximal conductance line (for example, following arrow a2 in Fig. 3a) corresponds to an incremental variation of δQ↓ by ±e. Here, ‘modified’ alludes to the fact that these continuous oscillations are in fact coherent AB oscillations modified by the Coulomb interaction. Likewise, crossing a phase jump line (for example, following arrow a1 in Fig. 3a) implies a change of the upper LL’s charge δQ↑ by ±e. Naturally, the combination of these two types of processes gives rise to the system’s charge stability diagram in the B−VMG plane.

To express the modified periodicities ΔB(m) and  (in between abrupt changes of the charge), we need to determine an expression for the interference phase (equation (5)) for a fixed number of electrons in the upper LL. We first generalize the dependence of the area response on δB and δVMG by combining the results obtained in the previous sections:

(in between abrupt changes of the charge), we need to determine an expression for the interference phase (equation (5)) for a fixed number of electrons in the upper LL. We first generalize the dependence of the area response on δB and δVMG by combining the results obtained in the previous sections:  , where the last term represents phase jumps that accompany variations of δQ↑=±e (for further details see Supplementary Notes 2–3). This result is then plugged into the expression for the total phase (equation (5))15:

, where the last term represents phase jumps that accompany variations of δQ↑=±e (for further details see Supplementary Notes 2–3). This result is then plugged into the expression for the total phase (equation (5))15:

Note that the last term of the of the equation accounts for abrupt phase jumps. The respective modified periodicities are:

These two frequencies are notably a linear combination of the AB and CD frequencies (cf. equations (1, 2, 3, 4)):  and

and  . Constant flux lines of δφtot follow a negative slope in the B−VMG plane, similar to the pure AB case. We extract ΔB(m)=65.9 G and

. Constant flux lines of δφtot follow a negative slope in the B−VMG plane, similar to the pure AB case. We extract ΔB(m)=65.9 G and  from our data; each of these periodicities leads to an interaction parameter ξ=0.75±0.01. The periodicities associated with phase jumps are found to be

from our data; each of these periodicities leads to an interaction parameter ξ=0.75±0.01. The periodicities associated with phase jumps are found to be  and

and  (cf. equations (1, 2, 3, 4); see Supplementary Note 3 for details). We find this relation to be in agreement with the measured values. Note that these periodicities do not depend on the value of ξ.

(cf. equations (1, 2, 3, 4); see Supplementary Note 3 for details). We find this relation to be in agreement with the measured values. Note that these periodicities do not depend on the value of ξ.

Combining the modified periodicities (equations (9 and 10)) with the phase jump periodicities allows us to construct the charge stability diagram. Naturally, vectors connecting different cells in the diagram (Fig. 3a) represent different discrete charge variations (δQ↓,δQ↑)=(n,m) (cf. Supplementary Note 2). It is convenient to select the following basis (Fig. 3a):  and

and  . Here, a1 represents the process of moving one electron from the upper to the lowest LL (namely, n=1 and m=−1, as explained in ‘magnetic field variations’), while a2 represents adding one electron to the lowest LL and keeping the upper LL’s charge constant (namely, n=1 and m=0). Evidently, their sum a1+a2 refers to adding one electron to the upper LL, while keeping the lowest LL’s charge constant. The reciprocal lattice is spanned by the pure AB and CD frequencies,

. Here, a1 represents the process of moving one electron from the upper to the lowest LL (namely, n=1 and m=−1, as explained in ‘magnetic field variations’), while a2 represents adding one electron to the lowest LL and keeping the upper LL’s charge constant (namely, n=1 and m=0). Evidently, their sum a1+a2 refers to adding one electron to the upper LL, while keeping the lowest LL’s charge constant. The reciprocal lattice is spanned by the pure AB and CD frequencies,  and

and  respectively (cf. Fig. 3b).

respectively (cf. Fig. 3b).

Phase jumps and proposed experiments

Finally, we study qualitatively the phase jump taking place when a phase jump line is crossed, following an infinitesimal variation of either δB or δVMG. The acquired phase is given by15:

Evidently, in the extreme AB and CD cases this phase jump is zero (ξ=0) or unobservable (ξ=1), respectively. Experimentally, the value of ξ (0<ξ<1) can be deduced from directly measuring the phase jump (seen in Fig. 4c). We find ξ≈0.75 (similar to the value we obtained independently by comparing the measured frequencies with equations (9 and 10) of the previous section). This value of ξ corresponds to an area jump of 440 nm2 (cf. Fig. 4d).

A possible extension of our analysis to the FQHE regime is straightforward and results in a phase jump given by:

where θstat is the quasi-particles’ statistical braiding phase (for example,  for anyons at νB=1/3). While the difference between equation (11) and equation (12) is seemingly minute, its impact might be significant. It is apparent that, by probing Δθ in a fractional filling factor, the requirement for probing θstat is 0≤ξ<1. This requirement is to be compared with previous measurements that focused on a pure AB, ξ=0 and pure CD, ξ=1 (anyonic statistics cannot be probed). Breaking this dichotomy between the pure AB and pure CD regimes thus provides us with a toolbox to probe anyonic statistics.

for anyons at νB=1/3). While the difference between equation (11) and equation (12) is seemingly minute, its impact might be significant. It is apparent that, by probing Δθ in a fractional filling factor, the requirement for probing θstat is 0≤ξ<1. This requirement is to be compared with previous measurements that focused on a pure AB, ξ=0 and pure CD, ξ=1 (anyonic statistics cannot be probed). Breaking this dichotomy between the pure AB and pure CD regimes thus provides us with a toolbox to probe anyonic statistics.

We stress that the protocol to probe fractional statistics requires the study of the conductance as function of the magnetic field and the modulation-gate voltage (similarly to Figs 3a and 4a). This is needed to identify the regime of operation (the parameter ξ) with no ambiguity. Previous reports28,29 presenting conductance oscillations in fractional filling factors have failed to show such 2D scans of the conductance in a 2D parameter space, and were thus criticized for not excluding a CD behaviour, or for being otherwise inconclusive8,19,30. Other works, which did identify the regime of operation, simply failed to obtain an AB behaviour in fractional filling factors. These attempts utilized both large area and small area devices. For the former, Coulomb effects are expected to be negligible if a top gate is placed on top of the sample7,8 or an Ohmic contact is placed at the centre of the device22, rendering the regime of operation AB. Yet an AB interference pattern (observable in the integer quantum Hall effect regime) has not been observed for fractional filling factors. This might be attributed to a short coherence length of anyons in such relatively large devices. One may then resort to smaller FPIs. Unfortunately, reducing the device’s size leads to the undesired CD regime in the case of top-gated devices7,8, and, in the case of devices with Ohmic contacts at the centre, further miniaturization is limited. The device reported here, having an Ohmic contact placed outside its circumference, operates in a regime intermediate between AB and CD. Given the possibility to make the device’s size small in such a design, yet maintaining ξ<1 with a clear signature of coherent Aharonov–Bohm oscillations, presents us with an intriguing prospects: notwithstanding a short quasi-particle coherence length, coherency may still be maintained over the size of the interferometer. Interference signal, a smoking gun evidence for anyonic statistics, is then potentially observable.

Discussion

We provide here an experimental evidence of area modulations of a FPI implemented in the quantum Hall effect regime. These modulations stem from the minimization of the system’s energy, as the applied magnetic field and the modulation-gate voltage are varied. Our analysis does not rely on the coherent operation of the device. The measurement of the area modulations, though, could be realized through the observation of coherent interference oscillations. The area evolution consists of a continuous shrinking when increasing magnetic field, followed by an abrupt dilation.

We have employed a theoretical framework that accounts for both the AB and the CD, and a novel intermediate regime. The latter enables us to construct the system’s charge stability diagram as well, showing good agreement with a minimal theoretical model. Both the area breathing and the charge stability diagram are used towards a complete characterization of the device, the latter being hidden in the pure AB or CD limits.

Utilizing a similar interferometer operating in the intermediate regime in the domain of the FQHE regime is called for. The novelty of our device lies within the possibility to explore a wide range of the interaction parameter ξ, in which the quasi-particles’ braiding statistics is observable. In other words, our findings reported here pave a new path for probing anyonic statistics in the FQHE regime.

Methods

Ohmic contacts

As explained in the text, the ‘pure’ CD regime can be avoided through undermining the effect of Coulomb interactions. This can be achieved utilizing two different methods:

First: we place a grounded Ohmic contact inside the interferometer’s bulk, thus avoiding its charge quantization (cf. the device in Fig. 1b). The Ohmic contact consists of 106 nm Au/53 nm Ge/40 nm Ni alloyed to the heterostructure having a resistance of 500 Ω at zero magnetic field. This Ohmic contact is not resistively coupled to the edge (the observed coherent phase oscillations are evidence to that). This important point has been verified in a previous work (cf. Supplementary Fig. 9 in ref. 22), employing a more complex set-up. The latter consisted of a FPI with a centre contact and an additional QPC placed along the interferometer’s edge, allowing to reflect edge channels selectively into the centre Ohmic contact. Then, by measuring the current at the centre contact, we have verified that it is non-vanishing only once the chiral channel corresponding to the LLL is physically reflected into this contact.

Second: this consists of lowering the device’s charging energy, KEB. For this purpose, two schemes are available. One scheme consists of covering the whole area of the FPI by a metallic top gate, increasing its capacitance, thus lowering its charging energy7,8. This scheme has not been utilized in our measurements, but has been reported to work well for relatively large FPIs (areas >12 μm2)7,8, resulting in a ‘pure’ AB behaviour. On the other hand, devices of area <4 μm2 have been found to operate in the CD regime, even if covered by top gate7,8. This was attributed to the different scaling of the capacitances Ceb and Cbulk with area15. The other scheme relies on placing an Ohmic contact in the vicinity of the interferometer. The role of the Ohmic contact here can be understood through a mutual capacitance Cob between the Ohmic contact and the bulk, similar to the effect of top gates7,8; we find, though, that this placement of an Ohmic contact is substantially more effective than a top gate. The mutual capacitance effectively increases the capacitance of the bulk (Cbulk→Cbulk+Cob), accounting for the partial screening by the Ohmic contact, while keeping the capacitance between the edge and the bulk unchanged (Ceb→Ceb). This leads to a decrease of the interaction parameter, ξ (ξ=0.75 in the results reported here, compared with ξ=1 with top-gated devices of the same size 4 μm2). As is discussed in the main text, this new design gives rise to the intermediate regime.

Measurement techniques

Our electronic set-up for conductance measurements is depicted in the Fig. 1c. We note that two amplifiers were used in the course of our measurements; the first, a homemade voltage preamplifier at T=1 K having a gain factor ∼10 and a commercial amplifier (NF SA-220F5) at room temperature having a voltage gain ∼200.

All experiments are performed within 3He–4He dilution fridges. Electron temperatures are measured via shot-noise measurements by driving a variable d.c. source current at a centre frequency of 800 kHz and bandwidth of 10 kHz.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Sivan, I. et al. Observation of interaction-induced modulations of a quantum hall liquid’s area. Nat. Commun. 7:12184 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12184 (2016).

References

van Wees, B. J. et al. Observation of zero-dimensional states in a one-dimensional electron interferometer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 2523–2526 (1989).

Goldman, V. J. & Su, B. Resonant tunneling in the quantum Hall regime: measurement of fractional charge. Science 267, 1010–1012 (1995).

Yacoby, A., Heiblum, M., Mahalu, D. & Shtrikman, H. Coherence and phase sensitive measurements in a quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 4047–4050 (1995).

Chang, D.-I. et al. Quantum mechanical complementarity probed in a closed-loop Aharonov–Bohm interferometer. Nat. Phys. 4, 205–209 (2008).

Hackens, B. et al. Imaging Coulomb islands in a quantum Hall interferometer. Nat. Commun. 1, 39 (2010).

Hackens, B. et al. Imaging and controlling electron transport inside a quantum ring. Nat. Phys. 2, 826–830 (2006).

Ofek, N. et al. Role of interactions in an electronic Fabry-Perot interferometer operating in the quantum Hall effect regime. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 5276–5281 (2010).

Zhang, Y. et al. Distinct signatures for Coulomb blockade and Aharonov-Bohm interference in electronic Fabry-Perot interferometers. Phys. Rev. B 79, 241304 (2009).

Giesbers, A. J. M. et al. Correlation-induced single-flux-quantum penetration in quantum rings. Nat. Phys. 6, 173–177 (2010).

Finkelstein, G., Glicofridis, P. I., Ashoori, R. C. & Shayegan, M. Topographic mapping of the quantum hall liquid using a few-electron bubble. Science 289, 90–94 (2000).

de C. Chamon, C., Freed, D. E., Kivelson, S. A., Sondhi, S. L. & Wen, X. G. Two point-contact interferometer for quantum Hall systems. Phys. Rev. B 55, 2331–2343 (1997).

Stern, A. Non-abelian states of matter. Nature 464, 187–193 (2010).

Stern, A. & Halperin, B. Proposed experiments to probe the non-abelian ν=5/2 quantum Hall state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 016802 (2006).

Han, C., Park, J., Gefen, Y. & Sim, H.-S. Topological vacuum bubbles by anyon braiding. Nat. Commun. 7, 11131 (2016).

Halperin, B. I., Stern, A., Neder, I. & Rosenow, B. Theory of the Fabry-Pérot quantum Hall interferometer. Phys. Rev. B 83, 155440 (2011).

Rosenow, B. & Halperin, B. I. Influence of interactions on flux and back-gate period of quantum Hall interferometers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 106801 (2007).

Ngo Dinh, S. & Bagrets, D. A. Influence of Coulomb interaction on the Aharonov-Bohm effect in an electronic Fabry-Pérot interferometer. Phys. Rev. B 85, 073403 (2012).

Ngo Dinh, S., Bagrets, D. A. & Mirlin, A. D. Nonequilibrium functional bosonization of quantum wire networks. Ann. Phys. 327, 2794–2852 (2012).

von Keyserlingk, C. W., Simon, S. H. & Rosenow, B. Enhanced bulk-edge Coulomb coupling in fractional Fabry-Perot interferometers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 126807 (2015).

Aharonov, Y. & Bohm, D. Significance of electromagnetic potentials in the quantum theory. Phys. Rev. 115, 485–491 (1959).

Kastner, M. A. The single-electron transistor. Rev. Mod. Phys. 64, 849–858 (1992).

Choi, H. K. et al. Robust electron pairing in the integer quantum hall effect regime. Nat. Commun. 6, 7435 (2015).

Chklovskii, D. B., Shklovskii, B. I. & Glazman, L. I. Electrostatics of edge channels. Phys. Rev. B 46, 4026–4034 (1992).

Lee, W.-R. & Sim, H.-S. Capacitive interaction model for Aharonov-Bohm effects of a quantum Hall antidot. Phys. Rev. B 83, 035308 (2011).

McEuen, P. L., Foxman, E. B., Kinaret, J., Meirav, U. & Kastner, M. A. Self-consistent addition spectrum of a Coulomb island in the quantum Hall regime. Phys. Rev. B 45, 11419–11422 (1992).

Evans, A. K., Glazman, L. I. & Shklovskii, B. I. Coulomb blockade in the quantum-Hall-effect state. Phys. Rev. B 48, 11120–11127 (1993).

Rosenow, B. & Halperin, B. Influence of Interactions on flux and back-gate period of quantum Hall interferometers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 106801 (2007).

Camino, F. E., Zhou, W. & Goldman, V. J. e/3 Laughlin quasiparticle primary-filling ν =1/3 interferometer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 076805 (2007).

Willett, R. L., Nayak, C., Shtengel, K., Pfeiffer, L. N. & West, K. W. Magnetic-field-tuned aharonov-bohm oscillations and evidence for non-abelian anyons at ν =5/2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 186401 (2013).

McClure, D. T., Chang, W., Marcus, C. M., Pfeiffer, L. N. & West, K. W. Fabry-Perot interferometry with fractional charges. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 256804 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Moty Heiblum for his immense support and consulting with regards to all aspects of the undertaken work. We also thank Nissim Ofek for very useful comments and ideas; and Yonatan Cohen for sharing his insights and advice. We acknowledge the partial support of German Research Foundation (DFG) grant no. RO 2247/8-1, as well as the Minerva foundation, the U.S.-Israel Bi-National Science Foundation (BSF), the Israeli-German Foundation (GIF) and the European Research Council under the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC grant agreement no. 227716.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.S., H.K.C., J.P. and Y.G. contributed to the paper writing. I.S., H.K.C. and A.R. contributed to the sample design, device fabrication and data acquisition. I.S., H.K.C., J.P. and Y.G. contributed to the theoretical analysis. D.M. contributed to the electron-beam lithography. V.U. grew the heterostructures.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-9, Supplementary Notes 1-3 and Supplementary References (PDF 22192 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Sivan, I., Choi, H., Park, J. et al. Observation of interaction-induced modulations of a quantum Hall liquid’s area. Nat Commun 7, 12184 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12184

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12184

This article is cited by

-

Observation of electronic modes in open cavity resonator

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Anyonic interference and braiding phase in a Mach-Zehnder interferometer

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Impact of bulk-edge coupling on observation of anyonic braiding statistics in quantum Hall interferometers

Nature Communications (2022)

-

A tunable Fabry–Pérot quantum Hall interferometer in graphene

Nature Nanotechnology (2021)

-

Aharonov–Bohm effect in graphene-based Fabry–Pérot quantum Hall interferometers

Nature Nanotechnology (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.