Abstract

Multivalent effects dictate the binding affinity of multiple ligands on one molecular entity to receptors. Integrins are receptors that mediate cell attachment through multivalent binding to peptide sequences within the extracellular matrix, and overexpression promotes the metastasis of some cancers. Multivalent display of integrin antagonists enhances their efficacy, but current scaffolds have limited ranges and precision for the display of ligands. Here we present an approach to studying multivalent effects across wide ranges of ligand number, density, and three-dimensional arrangement. Using L-lysine γ-substituted peptide nucleic acids, the multivalent effects of an integrin antagonist were examined over a range of 1–45 ligands. The optimal construct improves the inhibitory activity of the antagonist by two orders of magnitude against the binding of melanoma cells to the extracellular matrix in both in vitro and in vivo models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multivalency describes the simultaneous binding of multiple ligands on one molecular entity to multiple receptors on another entity. Multivalent interactions require precise spatial orientation of ligands and receptors at the nanometer scale, and dysregulation can be responsible for progression of diseases, such as the metastasis of cancer. Integrins are a class of membrane-associated proteins that mediate cell attachment and motility through multivalent binding, and a subset of these proteins (such as αvβ3) bind to the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) tripeptide sequence motif of extracellular matrix proteins1,2. The expression of integrin αvβ3 is increased on certain tumour cells3, and antagonists, such as Cilengitide4, have shown efficacy in clinical trials for metastatic melanoma and glioblastoma5,6. Multivalent display of integrin antagonists has been used to enhance their efficacy2,7,8,9,10,11,12, but current scaffolds for the display of ligands have physical limitations that constrict the range and precision of multivalent arrangements that can be explored13. Herein, we present an approach to make ligand-conjugated scaffolds that supports comprehensive screening for multivalent effects across wide ranges of ligand number, density and three-dimensional arrangement.

Historically, the development of synthetic scaffolds at the nanometer scale for the multivalent display of ligands can be broken down into two strategies: step-by-step and shotgun. The step-by-step approach involves sequentially attaching individual, ligand-containing units through covalent bonds (Fig. 1a)14. In this case, the number of desired ligands dictates the number of required synthetic steps. Although this method yields more precision in terms of ligand number and relative orientation, in most cases, it is logistically impractical for valencies greater than ~10 ligands. In contrast, the shotgun approach involves the single-step coupling (or polymerization) of multiple ligands to a pre-existing scaffold, such as a dendrimer, gold nanoparticle, polymer or protein (Fig. 1b)15. Although this can lead to high valencies, it is at the expense of knowing the exact number and/or relative orientation of the ligands. Furthermore, shotgun methods often result in an unknown, complex mixture of species that may further complicate analysis of biological activity. Translation of nanotechnology to medical therapies relies on nanometer-scale scaffolds in which bioactive ligands can be displayed with a high degree of precision to facilitate optimization of biological activity16,17. Ideally, the synthesis of such scaffolds would be facile and flexible, allowing for the rapid study of bioactivity over a wide range of different ligand valencies and densities.

(a) Step-by-step syntheses afford an accurate valency but are limited to low numbers of ligands. (b) Shotgun methods provide high valencies but an error (ɛ) is associated with the number of ligands. (c) Scaffolds made using LKγ-PNA and nucleic acid (NA) allow access to multivalent assemblies with both high valencies and accurate ligand number. Valency of an LKγ-PNA-NA assembly is the product of the number of complementary binding sites incorporated into the NA (x) and the number of ligands displayed from each PNA oligomer (y).

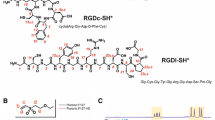

Here we present a scaffold and general strategy that overcomes the limitations of previous approaches (Fig. 1c). The core of the scaffold is a hybrid of peptide nucleic acid (PNA) and single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). PNA molecules are oligomers with a peptide-like backbone, typically formed from aminoethylglycine (aeg), with nucleic acid bases as sidechains (Fig. 2a). This allows for stable, complementary binding to DNA or RNA18,19. Substituting one or more of the regular aegPNA residues in the synthesis with a monomer that contains an attachment point allows cyclic-RGD-containing ligands, which are antagonists of αvβ3 integrins, to be placed anywhere along the PNA. For this step, we used L-lysine γ-substituted peptide nucleic acid (LKγ-PNA), whose lysine sidechain is available for conjugation and does not interfere with nucleic acid binding20,21,22. Finally, using nucleic acid-driven assembly of ligand-conjugated LKγ-PNA oligomers and ssDNA containing varying numbers of repeating complementary sequences, we can rapidly form libraries of multivalent molecules with precise numbers and densities of ligands (Figs 1c, 2b,c). For this report, we designed LKγ-PNA to control the assembly of a derivative of Cilengitide into fifty-two individual multivalent constructs over a range of 1–45 ligands that spanned different ligand arrangements and densities. The biological activities of each construct were examined and the optimal construct improves the inhibitory activity of the drug by two orders of magnitude against the binding of melanoma cells to the extracellular matrix in both in vitro cell-based and in vivo mouse models. We anticipate that scaffolds constructed from LKγ-PNA will greatly impact studies on multivalent display because the scaffold can be prepared with many different biological ligands and varied ranges of ligand valency, density and arrangement can be explored with high levels of precision for each construct.

Results

Multivalent library

To demonstrate the utility of our strategy, we developed a library of multivalent PNA–DNA complexes to block the attachment of metastatic melanoma cells to the extracellular matrix. For the ligand, we used a cyclic-RGD anlalogue, cycloArg-Gly-Asp-dPhe-Lys (c(RGDfK))4, with a short polyethylene glycol (PEG) linker to competitively bind to the αvβ3 integrins on the cell's surface. The c(RGDfK) ligand had previously been examined with valencies from 2 to 16 using step-by-step approaches3, and with average valencies between 13 and 52 with shotgun approaches3,23. In contrast, we designed a 52-member library that systematically varies the position, density and number of ligands from 1 to 45 (Fig. 3a). To modulate the positions and density of ligands, we synthesized four different 12-residue PNA oligomers: (A) single ligand at the amino-terminus, (B) single ligand at the centre, (C) two ligands, and (D) three ligands (B, C and D have the ligand attached through an LKγ-PNA sidechain, Supplementary Fig. S1). Each one of these PNAs was annealed with one of thirteen different ssDNAs with repeats of the complementary sequence from 1 to 15 (Supplementary Table S1). To identify each construct, we refer to a complex consisting of a ssDNA with x adjacent sequence repeats complementary to a PNA with sidechains as DNA:PNA-YX, where x is an integer from 1 to 15 and Y is a letter (A–D) representing one of the four different PNAs.

(a) Generation of the multivalent library by complexing each PNA in the first box with every DNA in the second box. PNA-A is an aegPNA oligomer with a c(RGDfK) bound to the N terminus. PNA-B, PNA-C and PNA-D have 1, 2 or 3 c(RGDfK) units, respectively, conjugated through γ-sidechains of internal LKγ-PNA residues. DNA is numbered according to how many complementary sequences each contains and represents the number of PNAs that would be complexed. Inhibition of C32 cell adhesion to vitronectin was examined with DNA:PNA complexes. (b) Three-dimensional representations of IC50 data from the screen of the library (A/B represents results from either PNA A or B). Data for DNA:PNA-C/D13−15 were not acquired because inhibitory activity was maximized at shorter lengths of ssDNA (see Supplementary Fig. S2 for error bars).

Cell-based screen for multivalent effects

The first test was a screen to determine the ability of each member of the library to prevent C32 human melanoma cells from attaching to a vitronectin–coated surface (Fig. 3a)24. The expression and specific function of αvβ3 integrin for attachment has been previously established for this cell line24. The experiments were controlled by the use of unattached c(RGDfK) molecules alone, which allowed results from different days to be normalized. Each experiment was performed at six different concentrations of each DNA:PNA-YX inhibitor, and each concentration was repeated in triplicate, to determine IC50 values. The results are shown in Figure 3b, Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary Table S2. As the inhibitory activities of PNAs A and B were similar, the two sets of results were combined into one series (A/B) in Figure 3b. When increasing the number of ligands per PNA from one to two to three (PNA A/B to C to D), the activity continually increases when each PNA is complexed to complementary DNA with one consensus sequence (IC50 values are 477, 169 and 67 nM, respectively, for DNA:PNA-Y1). This suggests that DNA:PNA-D1 can bind three αvβ3 integrin receptors simultaneously. We confirmed that such a multivalent interaction is sterically possible by developing an atomic-scale computer model of the complex with an arbitrary arrangement of the receptors in a cell membrane (Fig. 4). Increases in activities also occur as the number of consensus sequence repeats in the ssDNA increases. The results show that the activity plateaus at around 5–11 repeats of the consensus sequence in the ssDNA (depending on which PNA is used), with maximal improvement of inhibitory activity approximately two orders of magnitude greater than that of the c(RGDfK) control. The effect of increasing the distance between adjacent PNAs was examined with PNA-B and ssDNA consisting of complimentary consensus sequences that were separated by extra thymines (Supplementary Fig. S3). Although some improvement in activity was observed using DNA with two and three consensus sequences, the effect was not significant with longer DNAs. We interpret these data to indicate that proper spacing between ligands is important for interaction with multiple integrin receptors, but, at higher valencies, there is a local concentration effect that simultaneously contributes. These results are consistent with other multivalent assemblies of RGD7,25,26,27,28. Examination of the full multivalent landscape (Fig. 3b) allowed selection of the construct DNA:PNA-D5 for further binding and in vivo studies. This construct displays 15 cyclo-RGD ligands and was selected because it has the most potent inhibitory activity with the shortest ssDNA sequence.

Competition assay

Quantitative measurements of the dissociation constant for DNA:PNA-D5 binding to αvβ3 were conducted using competitive displacement experiments against radiolabeled 125I-echistatin binding to C32 melanoma cells. Echistatin is a 49 residue snake-venom peptide with a single RGD motif that binds strongly to αvβ3 (Kd=0.3 nM) and other integrins29. The displacement curves for individual tests of DNA:PNA-D5 and the c(RGDfK) control are shown in Figure 5a. Similar to the previous results (Fig. 3b), the multivalent DNA:PNA-D5 has a dissociation constant, two orders of magnitude lower than monovalent c(RGDfK) (Kd values of 0.16 versus 62.9 nM, respectively). The displacement of 125I-echistatin further confirms that the RGD ligands of DNA:PNA-D5 bind to the receptor sites on the integrins.

(a) Displacement of 125I-Echistatin from integrin αVβ3 on C32 cells by c(RGDfK) and DNA:PNA-D5. Kd c(RGDfK)=6.3×10−8 M; Kd DNA:PNA-D5=1.6×10−10 M. Error bars represent 2 s.d. (n=3). (b) The effect of DNA:PNA-D5 on metastatic potential of B16F10 cells based on the tumour development in C57BL/6NCr mice. All mice were injected with 5×105 B16F10 cells. Error bars represent 1 s.d. (n=8 mice). (c) Lungs of killed mice after fixation with tumour lesions indicated by dark spots. The mice treated with DNA:PNA-D5 had visibly fewer tumour colonies present after 14 days compared with the control or c(RGDfK) alone. Each row corresponds to three mice out of a group of eight. (d) Absorbance c(s) distributions obtained from sedimentation velocity data collected at 50 krpm and 20 °C for DNA:PNA-B5 at loading concentrations of 0.35 (blue), 0.78 (red) and 1.47 (green) A260. The complex was prepared using a slight excess of PNA seen at ~1.0 S.

In vivo activity

Next, we investigated the in vivo activity of DNA:PNA-D5 using a mouse melanoma cell line (B16F10). In vitro analysis using the aforementioned cell-adhesion assay showed B16F10 cells responded to the DNA:PNA constructs in a manner consistent with C32 cells (Supplementary Table S3). B16F10 cells injected into the tail vein rapidly metastasize and form tumours in the lungs30. This mouse model was selected over subcutaneous models because the mechanism of Cilengitide is known to inhibit metastasis under these conditions and provides direct evidence of any improvement owing to multivalent effects31,32. Previous studies have demonstrated that lung colonization by B16F10 cells in this experimental metastasis model can be significantly reduced through the use of integrin receptor ligands31,32. Compared with the control group receiving only B16F10 cells, mice dosed with 2 mgs of unconjugated c(RGDfK) (2.4 μmol) showed about a 30% reduction in tumour colonies on killing (Fig. 5b,c) after 14 days. However, mice that were treated with 0.1 mg of DNA:PNA-D5 (1.7×10−3 μmol of complex, or 2.6×10−2 μmol c(RGDfK), which amounts to 1% of the number of c(RGDfK) molecules relative to the control sample) showed an average reduction of ~50%. Thus, the efficacy of each c(RGDfK) unit appended to the DNA:PNA-D5 scaffold increased by about two orders of magnitude over c(RGDfK) alone. Mice treated with ssDNA or PNA alone, or with DNA:PNA complexes without attached c(RGDfK) ligands, did not exhibit any reduction in lung colonization.

Stoichiometry and stability

Finally, analytical ultracentrifugation was used to verify the stoichiometry and stability of the constructs. Although the DNA:PNA duplexes used in these studies are thermodynamically stable, as evidenced by annealing experiments, higher order complexes are harder to confirm, and cases of partial or nonspecific binding are difficult to identify. Accordingly, we tested DNA:PNA-B5, which should have 5 PNA-B molecules binding to 5 contiguous complementary sequence repeats in the ssDNA and is the same length as DNA:PNA-D5. Sedimentation experiments revealed its presence at 3.21S (Fig. 5d, s20,w=3.31S), and a hybrid local continuous/global discrete analysis yielded an average molecular mass of 43.9±1.1 kDa (42.41875 kDa predicted). Furthermore, the well-defined peak for the complex across multiple concentrations suggests that the DNA:PNA-B5 construct is not in equilibrium with remaining free PNA. Although PNA oligomers can aggregate in solution reducing the binding efficiency to complementary sequences, there was no evidence of unbound ssDNA.

Discussion

Complexes of DNA with ligand-modified LKγ-PNA should be a general strategy used to overcome the limitations of traditional nanometer-sized scaffolds and accurately control the presentation of biological ligands. Notably, the ability to rapidly produce a systematically varied library over a broad range of valencies and geometries allows for a clear determination of the optimal configuration. In this case, it was relatively simple to identify the multivalent DNA:PNA-D5 construct with 15 c(RGDfK) ligands to inhibit αvβ3 integrin binding with activity two orders of magnitude greater than c(RGDfK) alone in both in vitro and in vivo assays. At the present time, it is not clear why improvement of multivalent activity levels off at around 15 ligands, but we hypothesize that steric crowding of integrin receptors prevents higher valency constructs from contributing extra benefits to activity. On the basis of recent clinical data with Cilengetide5,6, it's likely the DNA:PNA-D5 construct alone does not have therapeutic value; however, in combination with imaging or chemotherapeutic agents it could be beneficial for tumour targeting3,4.

Compared with other multivalent RGD constructs in the literature that explore similar valency levels, our optimized scaffold demonstrates remarkable activity. For example, a regioselectively addressable functionalized template based on a cyclic decapeptide scaffold was made through step-by-step synthesis with 16 RGD ligands, but it did not show improved activity compared with the same scaffold with a valency of 2 ligands12. Another study explored a shotgun approach where RGD was conjugated to an antibody to achieve an average valency of 13 ligands per protein and an improvement in activity of each RGD by about 32 times compared with the monovalent ligand33. Each of these studies, however, examined only 5 different multivalent assemblies, probably due to the labour associated with preparing the scaffolds and conjugating the ligand. In our approach, we were able to screen 52 different multivalent assemblies over a valency range of 1–45 ligands to find an optimal one that improved the potency of each RGD ligand by about 2 orders of magnitude. We believe this strategy, in addition to a recently published γ-Cys-version22, could greatly aid the exploration of multivalent assemblies, especially if incorporated with other strategies to manipulate the three-dimensional architecture of DNA34.

Methods

Synthesis of PNA

Commercial-grade reagents and solvents were used without further purification except as indicated. The resin (MBHA, 100–200 mesh, 1% divinylbenzene, 0.3 mmol g−1, Advanced Chemtech) was prepared by swelling in DCM and downloading the resin with Boc-protected 3,6-dioxaoctanoic acid (mPEG) to 0.1 mmol g−1 capacity. Boc-protected aegPNA monomers were purchased from PolyOrg. PNA oligomer synthesis was carried out on a 5 μmol scale on an Applied BioSystems 433A Automated Peptide Synthesizer. Resin was swelled with DCM for 90 min before synthesis. LKγ-PNA Monomer was synthesized according to published procedures35. Activated LKγ-PNA monomer was allowed 180 min to couple. A further treatment of trifluoroacetic acid deprotection solution was also used to deblock LKγ-PNA residues. The lysine sidechains of LKγ-PNA monomers (Fmoc) were orthogonally deprotected with 20% piperidine in DMF. When multiple LKγ-PNA residues were present in the PNA oligomer (PNA-C and PNA-D; Fig. 3a), the primary amines on the sidechains were deprotected and coupled to mPEG residues in tandem. Purification of PNA oligomers was carried out using an XBridge Prep. BEH 130 C18 5 μm (10 mm×250 mm) column on an Agilent 1100 HPLC. In all cases, 0.05% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid and acetonitrile were used as solvents.

Preparation of multivalent constructs

A solution of LKγ-PNA (1.5 μmol), 3,4-diethoxy-3-cyclobutene-1,2-dione (45 μmol, 30 equiv.), triethylamine (90 μmol, 60 equiv.), 500 μl of anhydrous DMSO and 250 μl of absolute ethanol was mixed for 3 h. The solution was concentrated and the residue was washed with diethyl ether (3×1.0 ml), and dried under vacuum to produce the squaric-acid-conjugated PNA intermediate as a white solid. The above PNA intermediate was added to a solution of c(RGDfK(PEG–PEG) (30 μmol, 20 equiv., Peptides International), triethylamine (45 μmol, 30 equiv.) in 500 μl of anhydrous DMSO and 250 μl of absolute ethanol. After 18 h of shaking, the solution was concentrated. The residue was purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (19 mm×150 mm Waters C8 reverse-phase column, 12 ml min−1 flow rate, 0.1% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid and acetonitrile) to obtain the final product (57–90% yield over two steps) as a white solid. Conjugates were characterized by mass spectrometry using an Agilent 1200 series quadrupole LC/MSD electrospray trap (Supplementary Table S4). To make PNA:DNA complexes, a 1× PBS buffer solution of 20 μM DNA (Supplementary Table S1, Integrated DNA Technologies) was combined with the appropriate concentration of PNA conjugate depending on the repeat unit number on the DNA (ultraviolet quantification was performed using either a Nanodrop ND 1000, or an Agilent 8453 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer) at 25 °C. The solution was heated to 92 °C and held for 5 min, and then slowly cooled down to 25 °C over a period of 3 h.

Cell culture and cell attachment assay

C32 and B16F10 cells were maintained in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine, and penicillin and streptomycin in an incubator at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The cell attachment assay was carried out as previously described36. Collagen Type I was purchased from Advanced BioMatrix. Vitronectin, bovine serum albumin (BSA), Bouin's solution, and Echistatin were purchased from Sigma. 96-well flat-bottom plates were purchased from NUNC. All other cell culture media and medium supplements were purchased from Gibco. Either collagen Type I or vitronectin diluted in Dulbecco's PBS (DPBS without Ca2+, Mg2+) was coated onto 96-well flat-bottom plates (NUNC) overnight at 4 °C. After aspiration of the buffer, nonspecific adherence to plastic was blocked by incubation with DPBS containing 1% BSA at room temperature for 30 min. Cells were collected and washed in DPBS and resuspendend at 1×106 cells ml−1 in serum-free RPMI1640 containing 0.1% BSA. Aliquots of cells (50 μl) were added to each well containing 50 μl of the indicated concentrations of c(RGDfV) or PNA construct diluted in serum-free RPMI1640 containing 0.1% BSA. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 45 min to allow the cells attach to the plate. After the incubation, medium was discarded and nonadherent cells were removed by washing the plate with DPBS (with Ca2+, Mg2+). The number of adherent cells was quantified using the previously described colorimetric hexosaminidase assay37.

Molecular modelling

Atomic-scale, computer models were developed with the QUANTA Modelling Environment software program (Accelrys). The models were illustrated with the UCSF Chimera package from the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (supported by NIH P41 RR001081)38. The extended αvβ3 integrin model was developed from the crystal structure of a 'bent' conformation, as described by Xiong et al. (PDB accession code: 1JV2)39. The c(RGDfV) moiety was positioned analogous to the cyclic-RGD anlalogue in the subsequent αvβ3 integrin crystal structure: PDB accession code: 1L5G40. The DNA:PNA-Yx construct models were developed from PDB accession code: 1PDT41.

125I-Echistatin competition assay

Echistatin iodination was carried out by the Chloramine T (N-chloro tosylamide) method42. This procedure typically yielded a specific activity of 17.5 μCi μg−1. Competitive binding assays were carried out using a fixed amount of radioactive tracer added to varying concentrations of unlabelled competitor in the presence of 105 C32 cells per tube. Triplicate samples were incubated at 25 °C on a rocking platform. Bound and free ligands were separated by centrifugation through a Nyosol M25 oil cushion. Nonspecific binding was assessed using 20-fold excess unlabelled echistatin as a competitor. The success of a PNA-binding experiment was assessed by a comparison with a competitive displacement experiment using c(RGDfK) peptide carried out at the same time. The data was non-linearly fit to the 2-ligand, single receptor, heterologous displacement model using the LIGAND software program43. For this, the echistatin association constant for binding to αvβ3 integrin was fixed at the published value of 3.33×109 M (ref. 42).

Animals and tumour metastasis assay

Eight-to-ten week old female C57BL/6NCr mice were obtained from Charles River. All animal protocols used in this study were approved by the National Cancer Institute Animal Safety and Use Committee. All in vivo studies were conducted using DNA with phosphorothioate overhangs on each side to retard any degradation in vivo44. B16F10 cells were detached from culture flask and resuspended to 5×106 ml−1. Cyclo-RGD or PNA complex was then mixed with cells and 0.2 ml aliquots containing 2 mg of RGD, 100 μg of PNA complex, or PBS and single-cell suspensions of 5×105 cells were injected slowly into the lateral tail vein. Fourteen days later the animals were euthanized with CO2 and their lungs were excised and fixed in Bouin's solution. The number of surface melanoma colonies was counted visually.

Sedimentation studies on the DNA:PNA-B5 complex

Sedimentation velocity experiments were performed on the DNA:PNA-B5 complex prepared with a slight excess of PNA-B. Initial c(s) analyses were consistent with the presence of both a DNA:PNA-B5 complex at 3.20 S (uncorrected) and excess monomeric and dimeric PNA-B. The well-defined peak for the complex observed at all loading concentrations, together with a constant loading ratio of free PNA-B to complex, would suggest that these species are not in equilibrium with each other. Consequently, the appropriate c(s) analysis should allow for an estimate of the complex molecular mass. A two-dimensional c(s, f/fo) model was initially implemented45. At all concentrations studied, the projected c(s,*) distribution shows the presence of the complex at 3.21±0.02 S, corresponding to an s20,w of 3.31±0.02 S, as well as monomeric and dimeric PNA-B (Fig. 3a). On the basis of the best-fit average f/fo of 1.95 for the complex, a value consistent with the expected asymmetry of the double-stranded complex, an average molecular mass of 46.0 kDa is estimated for the complex. Although this value is slightly larger than that expected for the 5:1 complex that has a calculated mass of 42.41875 kDa, it supports the 5:1 stoichiometry for the complex. Data were analysed on terms of a hybrid local continuous/global discrete model in SEDPHAT. In this model, the excess PNA-B is accounted for in terms of a continuous c(s) distribution, whereas the complex is modelled as a discrete species with single values for s, M and f/fo. Experiments carried out at three loading concentrations yield identical results, within the error of the method, returning an average s20,w of 3.31±0.004 S and an average molecular mass of 43.9±1.1 kDa supporting a 5:1 stoichiometry for the DNA:PNA-B5 complex (n=1.03±0.03). Sedimentation experiments on the 60-base ssDNA show that this is a monodisperse monomer with a sedimentation coefficient of 2.771±0.007 S and a partial specific volume of 0.541 cm3 g−1. Similar experiments on a complementary 12-base PNA show that this self-associates to form a dimer with a Kd of 0.85±0.2 μM. Further sedimentation velocity controls can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Englund, E.A. et al. Programmable multivalent display of receptor ligands using peptide nucleic acid nanoscaffolds. Nat. Commun. 3:614 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1629 (2012).

References

Campbell, I. D. & Humphries, J. M. Integrin structure, activation, and interactions. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a004994 (2011).

Nemeth, J. A. et al. Aplha-v integrins as therapeutic targets in oncology. Cancer Invest. 25, 632–646 (2007).

Auzzas, L. et al. Targeting αvβ3 integrin: design and applications of mono- and multifunctional RGD-based peptides and semipeptides. Curr. Med. Chem. 17, 1255–1299 (2010).

Mas-Moruno, C., Rechenmacher, F. & Kessler, H. Cliengitide: the first anti-angiogenic small molecule drug candidate. design, synthesis and clinical evaluation. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 10, 753–768 (2010).

Stupp, R. et al. Phase I/IIa study of cilengitide and temozolomide with concomitant radiotherapy followed by cilengitide and temozolomide maintenance therapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 2712–2718 (2010).

Bradley, D. A. et al. Cilengitide (EMD 121974, NSC 707544) in asymptomatic metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer patients: a randomized phase II trial by the prostate cancer clinical trials consortium. Invest. New Drugs 29, 1432–1440 (2011).

Thumshirn, G., Hersel, U., Goodman, S. L. & Kessler, H. Multimeric cyclic RGD peptides as potential tools for tumor targeting: solid-phase peptide synthesis and chemoselective oxime ligation. Chem. Eur. J. 9, 2717–2725 (2003).

Lee, B. W. et al. Strongly binding cell-adhesive polypeptides of programmable valencies. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 1971–1975 (2010).

Jin, Z. H. et al. Effect of multimerization of a linear Arg-Gly-Asp peptide on integrin binding affinity and specificity. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 33, 370–378 (2010).

Galibert, M. et al. Application of click-click chemistry to the synthesis of new multivalent RGD conjugates. Org. Biomol. Chem. 8, 5133–5138 (2010).

Temming, K., Schiffelers, R. M., Molema, G. & Kok, R. J. RGD-based strategies for selective delivery of therapeutics and imaging agents to the tumour vasculature. Drug Resist. Updat. 8, 381–402 (2005).

Garanger, E., Boturyn, D., Coll, J.- L., Favrot, M.- C. & Dumy, P. Multivalent RGD synthetic peptides as potent αvβ3 integrin ligands. Org. Biomol. Chem. 4, 1958–1965 (2006).

Wang, J., Tian, S., Petros, R. A., Napier, M. E. & Desimone, J. M. The complex role of multivalency in namoparticles targeting the transferring receptor for cancer therapies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 11306–11313 (2010).

Kiessling, L. L., Gestwicki, J. E. & Strong, L. E. Synthetic multivalent ligands in the exploration of cell-surface interactions. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 4, 696–703 (2000).

Subbiah, R., Veerapandian, M. & Yun, K. S. Nanoparticles: functionalization and multifunctional applications in biomedical sciences. Curr. Med. Chem. 17, 4559–4577 (2010).

Mammen, M., Choi, S. K. & Whitesides, G. M. Polyvalent interactions in biological systems: implications for design and use of multivalent ligands and inhibitors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37, 2754–2794 (1998).

Giljohann, D. A. et al. Gold nanoparticles for biology and medicine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 3280–3294 (2010).

Egholm, M. et al. PNA hybridizes to complementary oligonucleotides obeying the Watson-Crick hydrogen-bonding rules. Nature 365, 566–568 (1993).

Nielsen, P. E. Peptide Nucleic Acids (PNA) in chemical biology and drug discovery. Chem. Biodivers. 7, 786–804 (2010).

Englund, E. A. & Appella, D. H. γ-substituted peptide nucleic acids constructed from L-lysine are a versatile scaffold for multifunctional display. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 1414–1418 (2007).

Gorska, K., Huang, K. T., Chaloin, O. & Winssinger, N. DNA-templated homo- and heterodimerization of peptide nucleic acid encoded oligosaccharides that mimic the carbohydrate epitope of HIV. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 7695–7700 (2009).

Scheibe, C., Bujotzek, A., Dernedde, J., Weber, M. & Seitz, O. DNA-programmed spatial screening of carbohydrate-lectin interactions. Chem. Sci. 2, 770–775 (2011).

Montet, X., Funovics, M., Montet-Abou, K., Weissleder, R. & Josephson, L. Multivalent effects of RGD peptides obtained by nanoparticle display. J. Med. Chem. 49, 6087–6093 (2006).

Sipes, J. M., Krutzsch, H. C., Lawler, J. & Roberts, D. D. Cooperation between throbospondin-1 type 1 repeat peptides and αvβ3 integrin ligands to promote melanoma cell spreading and focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 22755–22762 (1999).

Cavalcanti-Adam, E. A. et al. Cell spreading and focal adhesion dynamics are regulated by spacing of integrin ligands. Biophys. J. 92, 2964–2974 (2007).

Arnold, M. et al. Induction of cell polarization and migration by a gradient of nanoscale variations in adhesive ligand spacing. Nano Lett. 8, 2063–2069 (2008).

Chakraborty, S. et al. Evaluation of 111In-labeled cyclic RGD peptides: tetrameric not tetravalent. Bioconjug. Chem. 21, 969–978 (2010).

Kubas, H. et al. Multivalent cyclic RGD ligands: influence of linker lengths on receptor binding. Nucl. Med. Biol. 37, 885–891 (2010).

Marcinkiewicz, C., Vijay-Kumar, S., McLane, M. A. & Niewiarowski, S. Significance of RGD loop and C-terminal domain of echistatin for recognition of αIIbβ3 and αvβ3 integrins and expression of ligand-induced binding site. Blood 90, 1565–1575 (1997).

Fidler, I. J. Biological behavior of malignant melanoma cells correlated to their survival in vivo. Cancer Res. 35, 218–224 (1975).

Oliva, I. B. et al. Effect of RGD-disintegrins on melanoma cell growth and metastasis: involvement of the actin cytoskeleton, FAK and c-Fos. Toxicon 50, 1053–1063 (2007).

Ramos, O. H. et al. A novel αvβ3-blocking disintegrin containing the RGD motive, DisBa-01, inhibits bFGF-induced angiogenesis and melanoma metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 25, 53–64 (2008).

Kok, R. J. et al. Preparation and functional evaluation of RGD-modified proteins as αvβ3 integrin directed therapeutics. Bioconjug. Chem. 13, 128–135 (2002).

Douglas, S. M. et al. Self-assembly of DNA into nanoscale three-dimensional shapes. Nature 459, 414–418 (2009).

Englund, E. A. & Appella, D. H. Synthesis of γ-substituted peptide nucleic acids: a new place to attach fluorophores without affecting DNA binding. Org. Lett. 7, 3465–3467 (2005).

Kuznetsova, S. A. et al. TSG-6 binds via its CUB_C domain to the cell-binding domain of fibronectin and increases fibronectin matrix assembly. Matrix Biol. 27, 201–210 (2008).

Landegren, U. Measurement of cell numbers by means of the endogenous enzyme hexosaminidase – applications to detection of lymphokines and cell-surface antigens. J. Immunol. Methods 67, 379–388 (1984).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF chimera – a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1621 (2004).

Xiong, J. P. et al. Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin alpha V beta 3. Science 294, 339–345 (2001).

Xiong, J. P. et al. Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin αVβ3 in complex with an Arg-Gly-Asp ligand. Science 296, 151–155 (2002).

Eriksson, M. & Nielsen, P. E. Solution structure of a peptide nucleic acid DNA duplex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3, 410–413 (1996).

Kumar, C. C. et al. Chloramine T-induced structural and biochemical changes in echistatin. FEBS Lett. 429, 239–248 (1998).

Munson, P. J. & Rodbard, D. Ligand – a versatile computerized approach for characterization of ligand-binding systems. Anal. Biochem. 107, 220–239 (1980).

Pandolfi, D., Rauzi, F. & Capobianco, M. L. Evaluation of different types of end-capping modifications on the stability of oligonucleotides toward 3′- and 5′-exonucleases. Nucleosides Nucleotides 18, 2051–2069 (1999).

Brown, P. H. & Schuck, P. Macromolecular size-and-shape distributions by sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation. Biophys. J. 90, 4651–4661 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Intramural Programs of the NIDDK and NCI at NIH. We thank Gail McMullen for assistance with mice, Sergio Coelho for assistance with photography, and George Leiman and Lisa Jenkins for helpful comments. We dedicate this paper to the memory of Dr. Ryan Monfeli.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.A.E. and D.W. performed the syntheses, characterizations and assemblies of all PNAs and associated complexes, H.F. and H.S. performed cell-based assays and in vivo studies, C.M.M. developed the conjugation procedure to attach ligands to PNAs, R.G. performed the analytical ultracentrifugation, G.M.-M., M.L.P., and D.D.R. performed the echistatin competition assays and provided and maintained all the cell lines, S.R.D. performed all the computer modelling. The manuscript was written by E.A.E., S.R.D. and D.H.A. The initial ideas were conceived by D.H.A.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S3, Supplementary Tables S1-S4, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 409 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Englund, E., Wang, D., Fujigaki, H. et al. Programmable multivalent display of receptor ligands using peptide nucleic acid nanoscaffolds. Nat Commun 3, 614 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1629

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1629

This article is cited by

-

Functionalized tetrahedral DNA frameworks for the capture of circulating tumor cells

Nature Protocols (2024)

-

Instructing cells with programmable peptide DNA hybrids

Nature Communications (2017)

-

Green fluorescent protein nanopolygons as monodisperse supramolecular assemblies of functional proteins with defined valency

Nature Communications (2015)

-

DNA-based digital tension probes reveal integrin forces during early cell adhesion

Nature Communications (2014)

-

Design of peptide affinity ligands for S-protein: a comparison of combinatorial and de novo design strategies

Molecular Diversity (2013)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.