Abstract

Surfaces of three-dimensional topological insulators have emerged as one of the most remarkable states of condensed quantum matter where exotic electronic phases of Dirac particles should arise. Here we report on superconductivity in the topological insulator Sb2Te3 with transition to zero resistance induced through a minor tuning of growth chemistry that depletes bulk conduction channels. The depletion shifts Fermi energy towards the Dirac point as witnessed by a factor of 300 reduction of bulk carrier density and by the largest carrier mobility (≳25,000 cm2 V−1 s−1) found in any topological material. Direct evidence from transport, the unprecedentedly large diamagnetic screening, and the presence of ∼25 meV gaps detected by scanning tunnelling spectroscopy reveal the superconducting condensate to emerge first in surface puddles, with the onset of global phase coherence at ∼9 K. The rich structure of this state lends itself to manipulation via growth conditions and the material parameters such as Fermi velocity and mean free path.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Unconventional superconductivity involving electron bands with nontrivial topological character has been predicted1,2,3,4,5 to arise on the surfaces of three-dimensional topological insulators (TIs), where conduction channels host helical Dirac fermions6,7,8,9,10 that cannot be destroyed by non-magnetic scattering processes. Such topological superconductors are expected to host unusual Majorana modes1 with special non-Abelian statistics11 and usher in new approaches to quantum device engineering and materials science. The superconducting phases in topological insulators reported thus far, obtained for example, by Cu doping12,13,14 or under very high (GPa range) pressures15,16, were found to have increased bulk carrier densities12 and thus appear to be of bulk origin.

Here we report that surface superconductivity in the topological material Sb2Te3 with hole-like (p-type) bulk conduction can be induced at a remarkably high temperature by a very minor change in Te vapour pressure during the crystal growth. Tellurium overpressure makes no detectable structural changes, yet results in a sharply localized and evidently non-monotonic doping effect17,18: in this process electrons are supplied to the system in a narrow range of Te vapour pressure (in the vicinity of ∼1.4 MPa), reducing free hole density by over two orders of magnitude, as compared with the samples grown at higher or lower vapour pressures. The net effect is an upshift of the Fermi energy from the bulk valence bands towards the vicinity of the Dirac point, with concurrent enhancement of carrier mobility from the typical μ≲200 cm2 V−1 s−1 in the non-superconducting samples to the unprecedented value of ≳25,000 cm2 V−1 s−1 in the superconducting phase. The induced nonmonotonically doped state displays a superconducting resistive transition at a relatively high temperature Tc∼9 K. However, quite unexpectedly, the onset of enhanced diamagnetic response, as probed both by a.c. susceptometry and by superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometry, takes place well above this temperature. Furthermore, scanning tunnelling spectroscopy (STS) indicates a patchy landscape of superconducting regions with gaps in the differential conductance that can be locally as large as ∼25 meV. The dramatic reduction of net density of free and hugely mobile holes in the material’s bulk and electronic surface inhomogeneity, accompanied by large non-Landau fluctuation-like19 diamagnetic signal that displays strong field, temperature and frequency dependence, are all pointing to a non-trivial superconducting state. While the 9 K superconductivity at ambient pressure in a topological material with reduced carrier density is unusual in its own right, our observation of enhanced mobility and strong precursor effects at much higher temperatures points to an inchoate superconducting instability of topological surface states. Notwithstanding presently rudimentary undestanding of the connection between high temperature precursors and Tc itself, our results raise a possibility of engineering even higher transition temperatures through controlled tuning of charge doping during materials’ growth.

Results

Salient features of superconductivity in Sb2Te3

We begin by highlighting the most prominent features of our discovery. Fig. 1a shows resistivity of Sb2Te3 synthesized under ∼1.4 MPa Te vapour pressure during the high-temperature step of the crystal growth cycle (see Methods) and measured at ambient pressure. The system undergoes a transition to zero resistance at the onset temperature Tc≅8.6 K. We note that this is the highest transition temperature observed in a topological material at ambient pressure after synthesis (for chemical and structural analysis, and sample statistics see Methods, Supplementary Figs 1 and 2, and Supplementary Table 1). In the narrow Te pressure range 1.2<P<1.5 MPa, where superconductivity is found, the bulk hole density obtained from Hall resistivity is reduced by over two orders of magnitude (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1) to ≲1018 cm−3—a finding which should be contrasted with the increased electron density recorded in, for example, superconducting Bi2Se3 doped with Cu (ref. 12).

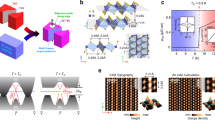

(a) Resistivity of an exfoliated 100-nm thin Sb2Te3 crystal synthesized under ∼1.4 MPa Te vapour pressure (see Methods) shows onset of transition to zero resistance at Tc ≅ 8.6 K. Inset shows Hall contact configuration used. Scale bar, 50 μm. (b) Diamagnetic susceptibility (blue) at 1.9 K measured in a 0.2 T field shows huge diamagnetism (Meissner effect) only in the narrow Te vapour pressure range. It is anticorrelated with the measured hole density (pink) which in the superconducting state is decreased by a factor of nearly 300. Outside this range samples are nonsuperconducting. (c–e) STM and STS scans performed at 4.8 K in areas ∼25 nm each, spaced ∼200 nm apart. (c) A typical topograph of a scanned area shows well ordered hexagonal lattice. Scale bar, 10 nm. (d) Illustration of superconductive puddles (blue, size 2R) of Dirac bands, where pairing occurs at high temperature (TCD), connected to the 2DEG metallic matrix (grey), which establishes a percolative path (dashed red line) at Tc. The electronic Dirac dispersion and spin-orbit split dispersion of 2DEG are also sketched. (e) Differential conductance dI/dV (from the average of 500 scans) displaying a gap and superconducting coherence peaks. Depending on the scan area, the gaps 2Δ vary from zero to ≳20 meV.

In the same narrow pressure range the diamagnetism is enhanced by two orders of magnitude (Fig. 1b) relative to the signal in samples outside the critical pressure range20. STS (Fig. 1c–e, also Methods, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 1) shows very flat hexagonally ordered surfaces and a clear presence of gaps in differential conductance dI/dV with clear coherence peaks (Fig. 1e) as well as more complex gap structures that can vary locally from 0 to ≳20 meV. This patchy gap landscape indicates a laterally inhomogeneous superconducting state which within BCS theory (using the BCS gap equation 2Δ(0)=3.5kBTc, where kB is the Boltzmann constant) has local transition temperatures that can be as high as 60 K, that is, much greater than the observed resistive Tc, but inline with the temperature at which the onset of the enhanced diamagnetic signal is observed discussed below.

Magnetic field-temperature phase diagram

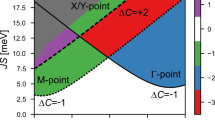

Next we turn to the finite field response of the superconducting state. The resistive transition downshifts and broadens with increasing external magnetic field (Fig. 2a,b). By tracking onset temperature Tc(H) we map the field-temperature H–T phase diagram for the two field orientations: applied along the c axis of the crystal, H || c, and parallel to the ab plane, H || ab (Fig. 2a,b, respectively). The low-temperature anisotropy of the field HR(T) shown in Fig. 2c (obtained from the resistive onset marked by arrows in Fig. 2a) at first glance is surprisingly small, only ∼1.4, given the large structural anisotropy of Sb2Te3 (Supplementary Figs 1 and 2). This anisotropy corresponds nearly exactly to the anisotropy of the g-factor detected by microwave spectroscopy21,  , an observation consistent with the limiting field being largely governed by spin rather than orbital effects. If indeed depairing is of paramagnetic (Zeeman) origin, a simple relationship between the paramagnetic field (so called, Chandrasekhar–Clogston limit), Hp, and the superconducting transition temperature Tc is conventionally obtained22 by comparing magnetic energy

, an observation consistent with the limiting field being largely governed by spin rather than orbital effects. If indeed depairing is of paramagnetic (Zeeman) origin, a simple relationship between the paramagnetic field (so called, Chandrasekhar–Clogston limit), Hp, and the superconducting transition temperature Tc is conventionally obtained22 by comparing magnetic energy  with the superconducting condensation energy

with the superconducting condensation energy  . Here N(0) is the density of states at the Fermi energy, g is the Landé g-factor and Δ(0) and Hp(0) are zero-temperature superconducting gap and paramagnetic limiting field, respectively. Equating the observed low temperature values of HR∼3–4 T with HP(0) and using large g values of ≅50 obtained in experiments23, we get an estimate of ∼60 K, which is substantially higher than Tc∼9 K but remarkably consistent with the scales of scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) gap values.

. Here N(0) is the density of states at the Fermi energy, g is the Landé g-factor and Δ(0) and Hp(0) are zero-temperature superconducting gap and paramagnetic limiting field, respectively. Equating the observed low temperature values of HR∼3–4 T with HP(0) and using large g values of ≅50 obtained in experiments23, we get an estimate of ∼60 K, which is substantially higher than Tc∼9 K but remarkably consistent with the scales of scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) gap values.

Resistive transition temperature downshifts with increasing magnetic field applied (a) along the c axis of the crystal, H || c, and (b) parallel to the ab plane, H || ab. The onset of superconductivity at the point of slope change is indicated by the arrows. (c) H–T phase diagram of the superconducting state has relatively small zero-temperature anisotropy of ∼1.4, the same as that of g-factor. The error bars represent the uncertainty in the onset temperature of the resistive downturn in R(T), estimated using the temperature difference between the onset of the resistive transition at Tc and the intersection point of straight lines extrapolated from the R(T) curve in the normal state and in the superconducting fluctuation regime. The critical field values at T→0 agree with the paramagnetic (Zeeman) depairing field HP. Inset: dHvA oscillations shown for H || c at 1.9 K persist below Hp down to the temperature dependent onset field H*.

Given this surprising disparity between the observed Tc=8.6 K and temperature scale deduced from limiting field (and STM gaps) it is only natural to consider the possibility of inhomogeneous superconducting state in Sb2Te3, with locally superconducting and normal-metal regions coexisting above and somewhat below the resistive transition. Another strong indication of the inhomogeneity comes in the appearance of pronounced de Haas–van Aphen (dHvA) quantum oscillations of magnetization in the superconductng state (inset in Fig. 2c and Fig. 3a,b). The amplitude of dHvA signal in our superconducting Sb2Te3 changes rather uneventfully across HR(T) and shows no additional damping below the limiting field (Supplementary Fig. 5). This is quite unlike a more conventional behaviour in uniform type II superconductors24, where dHvA oscillations are strongly damped at fields lower than the upper critical field, Hc2.

(a) dHvA oscillations show beats arising from two very close oscillation periods. The beats are a signature of spin-splitting by a strong spin-orbit interaction in 2DEG surface regions28. (b) Fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the signals clearly showing two close frequencies of the oscillations. (c) dHvA oscillations versus inverse transverse component of magnetic field H⊥=Hcosθ shown for three values of magnetic tilt angle θ. The observed constancy of beat nodes scaling with H⊥ is a characteristic signature of 2D. (d) Hole carrier density n versus Te pressure in the superconducting (cartooned by a Cooper pair) and non-superconducting (single particle cartoons) Sb2Te3. Outside the superconducting region (shaded area), carrier density n is relatively high and the Fermi level EF is deep inside the bulk valence band (BVB), as illustrated by the sketches of the band structure. In the superconducting (s.c.) region n is reduced, upshifting EF to just below the Dirac point (DP)(inset in b). There with Fermi level crossing both the Dirac bands and a 2DEG sliver of the BVB, the superconducting gap Δsc opens up and the beats in SdH are detected, with the bulk conduction band (BCB) unfilled and conductivity remaining hole-like (p-type).

de Haas van Alphen oscillations and 2DEG

Quantum dHvA oscillations are one of the most direct probes of quasiparticle excitations in metals25, and in superconducting Sb2Te3 are quite remarkable in their own right as they clearly display a beat structure (Figs 2c and 3a–c, Supplementary Figs 5 and 6 and Supplementary Note 2) similar to that found in spin-orbit coupled quantum well states in semiconductors26. Lifshitz–Kosevich analysis25 of these oscillations (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 2) yields vF≃5.3 × 105 ms−1, ℓ≈95 nm, m=0.065 me, kF+=3.7 × 108 m−1, kF−=3.3 × 108 m−1 for Fermi velocity, mean-free path, effective mass and the two close Fermi wave vectors that induce the beats, respectively. The overall beat structure appears to scale with the magnetic field component transverse to the surface as shown in Fig. 3c for three field orientations, suggestive of the two-dimensional (2D) character of the beat signal. Non-topological but largely 2D bulk-like states have been predicted in TIs in ab initio calculations27 and detected in angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy28 but, to the best of our knowledge, have never been observed in magnetooscillations—our observation may be the first such detection of such (sub)surface excitations. The peculiar dispersion of the bulk valence bands7 of Sb2Te3 suggests the mechanism by which Te overpressure promotes the visibility of 2D electron gas (2DEG; Fig. 3d)—in the narrow region of Te overpressure the hole density is severely reduced, bringing the Fermi level up to just below the Dirac point where it intersects the surface state and six small pockets of bulk bands which are expected to participate in band bending and surface reconstruction of electronic structure.

Huge carrier mobility consistent with surface transport

Carrier mobility can be estimated from either transport data or Dingle analysis25 of the dHvA data. A priori, these two methods need not agree and in the non-superconducting TIs, including Sb2Te3 (see Supplementary Table 2), this is the case; in transport the usual Drude description of conductivity mixes all participating bulk and surface channels (particularly when there are multiple pockets in the Brillouin zone) while dHdA is sensitive mostly to the highest mobility paths. Remarkably, in superconducting samples, we obtain very similar values of 25,000 cm2 V−1 s−1 and 26,600 cm2 V−1 s−1 from transport and dHvA, respectively, roughly within the experimental uncertainty (Supplementary Table 2). These values are exceptionally high compared to our non-superconducting samples (where mobility is a factor of ∼165 smaller and mean free path ℓ is a factor of four smaller,Supplementary Table 2), but also to the values in other TIs29,30,31. The consistency of both estimates and the appearance of hugely mobile holes in the superconducting state suggest that here mostly surface conducting channels are involved.

Unusual high-temperature diamagnetic response

Now, we return to examine the diamagnetic signal shown in Fig. 1b. Differential diamagnetic magnetic susceptibility  (Fig. 4a–c) measured using a relatively low (10 kHz) frequency is strongly field and temperature dependent. The signal persists to high temperatures as it smoothly and monotonically reduces to nonsuperconducting values. This unusual differential response is found to vary strongly with frequency of a.c. excitation even for the low (∼kHz) frequencies used (Fig. 4d,e). Conventional bulk superconductors do not exhibit such frequency dependence, however, inhomogeneous superconductors often do32,33 and therefore require a considerably more comprehensive and nuanced approach to reliably relate magnetic signatures to superconductivity, which we now present.

(Fig. 4a–c) measured using a relatively low (10 kHz) frequency is strongly field and temperature dependent. The signal persists to high temperatures as it smoothly and monotonically reduces to nonsuperconducting values. This unusual differential response is found to vary strongly with frequency of a.c. excitation even for the low (∼kHz) frequencies used (Fig. 4d,e). Conventional bulk superconductors do not exhibit such frequency dependence, however, inhomogeneous superconductors often do32,33 and therefore require a considerably more comprehensive and nuanced approach to reliably relate magnetic signatures to superconductivity, which we now present.

(a) Differential magnetic susceptibility  versus temperature for several values of magnetic field μ0H || c-axis. Meissner-like signal is flat below Tc and monotonically vanishes at much higher (>100 K) temperatures.

versus temperature for several values of magnetic field μ0H || c-axis. Meissner-like signal is flat below Tc and monotonically vanishes at much higher (>100 K) temperatures.  was measured by applying a small a.c. excitation field hac=10−5 T at f=10 kHz. (b) Full temperature and field dependence of

was measured by applying a small a.c. excitation field hac=10−5 T at f=10 kHz. (b) Full temperature and field dependence of  . (c)

. (c)  versus magnetic field μ0H || c axis for a series of temperatures. The pronounced dHvA oscillations are apparent at 1.9 K. (d)

versus magnetic field μ0H || c axis for a series of temperatures. The pronounced dHvA oscillations are apparent at 1.9 K. (d)  strongly depends on frequency. (e) Full frequency and temperature dependence of

strongly depends on frequency. (e) Full frequency and temperature dependence of  . (f) The prefactor b(T) in the

. (f) The prefactor b(T) in the  term dominates the total variation of

term dominates the total variation of  at finite frequencies. This variation is consistent with kinetic inductance of the patchy distributed 2DEG network discussed in the text. (g) The zero frequency

at finite frequencies. This variation is consistent with kinetic inductance of the patchy distributed 2DEG network discussed in the text. (g) The zero frequency  obtained from the fits to

obtained from the fits to  shows a sharp onset at TCD. Inset: Analysis of the frequency dependence of

shows a sharp onset at TCD. Inset: Analysis of the frequency dependence of  shows it to be quadratic in

shows it to be quadratic in  . (h) dc magnetization M(T) measured at 0.5 Oe using SQUID shows a sharp diamagnetic onset at the same TCD≈50 K>Tc. The data taken under zero-field-cooled (ZFC) and field-cooled (FC) conditions are essentially identical, consistent with negligible vortex pinning in 2D (ref. 22). We note that M(T)∝TCD—T as well the onset of

. (h) dc magnetization M(T) measured at 0.5 Oe using SQUID shows a sharp diamagnetic onset at the same TCD≈50 K>Tc. The data taken under zero-field-cooled (ZFC) and field-cooled (FC) conditions are essentially identical, consistent with negligible vortex pinning in 2D (ref. 22). We note that M(T)∝TCD—T as well the onset of  variation near TCD shown in (g) are both approximately linear in temperature, which within Ginzburg–Landau phenomenology22 (valid at high temperatures) would be related to magnetic penetration depth

variation near TCD shown in (g) are both approximately linear in temperature, which within Ginzburg–Landau phenomenology22 (valid at high temperatures) would be related to magnetic penetration depth  ,

,  .

.

General analyticity considerations at low external field dictate that low frequency dependence is analytic and can be approximated quadratically,  , and such behaviour is found in resistively shunted Josephson networks and other cases of two fluid (normal+superfluid) dynamics32. With this in mind we analysed the frequency dependence of

, and such behaviour is found in resistively shunted Josephson networks and other cases of two fluid (normal+superfluid) dynamics32. With this in mind we analysed the frequency dependence of  by performing frequency scans at different temperatures, focusing on the low field regime. The data (inset in Fig. 4g) clearly follows a parabolic frequency dependence. The fit to this simple form uncovers a spectacular dichotomy between temperature variation of the zero frequency value

by performing frequency scans at different temperatures, focusing on the low field regime. The data (inset in Fig. 4g) clearly follows a parabolic frequency dependence. The fit to this simple form uncovers a spectacular dichotomy between temperature variation of the zero frequency value  (Fig. 4g, Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 7) and the dispersion coefficient b(T) (Fig. 4f):

(Fig. 4g, Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 7) and the dispersion coefficient b(T) (Fig. 4f):  shows a sharp diamagnetic onset in the vicinity of ∼55 K, while the prefactor b(T) smoothly marches toward the near null value at very high temperatures (see also Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Note 4). For completeness, we also examined the imaginary part of magnetic susceptibility and it clearly exhibits conventional eddy current heating behaviour (Supplementary Fig. 8).

shows a sharp diamagnetic onset in the vicinity of ∼55 K, while the prefactor b(T) smoothly marches toward the near null value at very high temperatures (see also Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Note 4). For completeness, we also examined the imaginary part of magnetic susceptibility and it clearly exhibits conventional eddy current heating behaviour (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Mesoscopic superconducting puddles in Sb2Te3

This sharp variation of  is closely mirrored both in its saturation magnitude, ∼10−4 e.m.u. cm−3 (Fig. 4g), and in the onset temperature of 55 K in d.c. magnetization measured using SQUID (Fig. 4h). The absolute value of diamagnetic response obtained in these samples clearly exceeds those of typical topological insulators (and semiconductors generally) by at least two orders of magnitude20,34 but also the largest known diamagnetic susceptibilities of semimetals35,36,37. Thus, we identify the pronounced variation (with temperature, field and/or frequency) and the overall magnitude of the diamagnetic response with a mesoscopic Meissner transition near 50 K detected in SQUID (Fig. 4g). We observe that the finite frequency response coefficient, b(T), varies smoothly and persists to much higher temperatures (see Fig. 4f), well above 100 K—this indicates a distribution of superconducting regions (puddles). Significantly, both

is closely mirrored both in its saturation magnitude, ∼10−4 e.m.u. cm−3 (Fig. 4g), and in the onset temperature of 55 K in d.c. magnetization measured using SQUID (Fig. 4h). The absolute value of diamagnetic response obtained in these samples clearly exceeds those of typical topological insulators (and semiconductors generally) by at least two orders of magnitude20,34 but also the largest known diamagnetic susceptibilities of semimetals35,36,37. Thus, we identify the pronounced variation (with temperature, field and/or frequency) and the overall magnitude of the diamagnetic response with a mesoscopic Meissner transition near 50 K detected in SQUID (Fig. 4g). We observe that the finite frequency response coefficient, b(T), varies smoothly and persists to much higher temperatures (see Fig. 4f), well above 100 K—this indicates a distribution of superconducting regions (puddles). Significantly, both  and b in relatively thick (∼mm size) samples exhibit a large field anisotropy (Fig. 4f) consistent with the 2D nature of diamagnetic response and with the surface origin of the signal. Notably, the mesoscopic diamagnetic transition near 50–55 K is also mirrored in transport, whereby resistivity exhibits a clear downward step that broadens and disappears in finite fields, consistent with the existence of finite-sized superconducting shorts inside the sample (Supplementary Fig. 9).

and b in relatively thick (∼mm size) samples exhibit a large field anisotropy (Fig. 4f) consistent with the 2D nature of diamagnetic response and with the surface origin of the signal. Notably, the mesoscopic diamagnetic transition near 50–55 K is also mirrored in transport, whereby resistivity exhibits a clear downward step that broadens and disappears in finite fields, consistent with the existence of finite-sized superconducting shorts inside the sample (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Discussion

There are three most noteworthy aspects of the new electronic state in Sb2Te3. One is the uncovered extreme sensitivity to the growth parameters that reveals an instability to strong correlations, leading to our discovery of superconductivity at ambient pressure and relatively high temperature of ∼8.6 K. It illuminates a path to topological superconductivity by fine-tuned doping control. Another is its likely surface origin as seen through the unexpectedly suppressed bulk charge carrier density, orders-of-magnitude enhanced carrier mobility and extreme anisotropy of diamagnetic screening. And the third is a clear evidence of mesoscopic either remnants or precursors persisting to much higher temperatures, detected by four kinds of independent probes employed in our studies, namely, transport, a.c. susceptibility, d.c. magnetization, and STM and witnessed by a distinct (low) frequency response.

Resemblant precursor effects are well established in systems where superconducting grains are imbedded in a metallic or insulating matrix38,39,40. It should be noted that puddles have been known to form at low carrier densities in other 2D Dirac systems41 owing to nonlinear screening effects42,43 and surface Dirac puddles have been reported in STS studies of doped nonsuperconducting TIs44. So it is natural to ask what additional insights might be attained if we consider the existence of similar mesoscopic structures imbedded in the high mobility metallic matrix apparent from our dHvA results.

To start then, we expect that the observed resistive transition is due to percolation of proximity induced couplings, that is, it is not of BCS mean-field character and should exhibit different (stronger) fluctuation effects19. Well below the resistive transition the mesoscopic character of the state is lost due to proliferation of such proximity couplings, that is, the gap function is expected to decay very slowly inside the metallic matrix. Our low temperature STM scans have uncovered inhomogeneity in the gap function on very long scales, larger than available sampling density of regions (Supplementary Fig. 4), which is fully consistent with the dominance of proximity coupling for T<Tc≈9 K. The percolative model of the transition38,45 allows us to obtain rough estimates of interpuddle spacing a and puddle size R, which we now summarize (a more detailed discussion is in Supplementary Notes 4 and 5). The typical interpuddle distance must be comparable to the diffusive length LT of the metallic matrix at Tc, a≈LT. We estimate LT from the dHvA data to be ≈140 nm. Assuming that all puddles reside on the surface allows us to estimate the total number of puddles in the sample (≲109) and, furthermore, the typical puddle’s lateral size, R≈37 nm, from the observed magnetization signal at low fields directed along the c axis. This phenomenological analysis consistently and quantitatively connects all of the low temperature experimental observations, including the resistive transition, its inhomogeneous and nearly isotropic suppression in strong fields, strong anisotropy of the diamagnetic screening, and STM maps.

Local superconductivity on mesoscopic scales in the globally normal state should be detectable as fluctuation-like phenomena in resistivity and other probes, including magnetization. At the simplest (mean field) level we expect that for a single superconducting puddle smaller than penetration depth,  , in the otherwise normal metal to contribute

, in the otherwise normal metal to contribute  to the diamagnetic susceptibility46 and a downward step22 in resistivity R(T). Magnetization data (Fig. 4g,h) and transport (Supplementary Fig. 9) appear to consistently support the existence of an intra-puddle mean-field transition near T≈50 K, which is both much higher than Tc but also relatively sharp, hinting at the mono-dispersity of puddle distribution. Observation of such high temperature scale for the local mesoscopic transition is unprecedented in this or any other semiconductors.

to the diamagnetic susceptibility46 and a downward step22 in resistivity R(T). Magnetization data (Fig. 4g,h) and transport (Supplementary Fig. 9) appear to consistently support the existence of an intra-puddle mean-field transition near T≈50 K, which is both much higher than Tc but also relatively sharp, hinting at the mono-dispersity of puddle distribution. Observation of such high temperature scale for the local mesoscopic transition is unprecedented in this or any other semiconductors.

Although several of our experimental findings can be consistently understood in the phenomenological framework of superconductor-metal composite system, the nature of the putative superconductivity in the puddles remains to be elucidated. For one, the weak anisotropy of the resistive limiting field implies that spin physics and spin-orbit coupling play a significant role in establishing the resistive H versus T phase diagram via paramagnetic depairing mechanism22. Also mesoscopic fluctuations in the effective Josephson network governing the resistive transition45 must play a role in the observed variations in transport and in significant superconducting fluctuations at high temperatures. We remark that 2D superconductivity that has been found in 2DEG at the interfaces between two band insulators, LaAlO3 and SrTiO3 occurs below 200 mK (ref. 47), a much lower temperature than we observe; the much higher Tc in Sb2Te3 is a likely spillover from the superconducting puddles48 supporting pairing of helical Dirac holes.

Methods

Crystal growth

Single crystals of Sb2Te3 were grown in evacuated quartz tubes in a horizontal gradient furnace heated to 1,000 °C and cooled to room temperature in 7–10 days. The starting materials used were cm-sized chunks of Sb (purity 99.9999%) and Te (purity 99.9995%) from Alfa Aesar used in stoichiometric ratios. We made over 20 crystal growth runs under similar growth conditions and screened all samples, usually approximately millimetre in size, for their overall diamagnetic response using a.c. susceptibility first. The critical parameter was Te pressure during the high temperature segment of the growth process; it was determined from the ideal gas equation P=nRTmax/V, where Tmax is the highest temperature used, V is the enclosed volume, n is the umber of moles of the material and R is the ideal gas constant; it was consistent with equilibrium binary phase diagram of Sb–Te (ref. 49).

Chemistry of crystal growth from the stoichiometric melt in a fixed volume at high (1,000 °C) temperature sets the stoichiometry of the final crystal product. To finetune Te pressure for each crystal growth run we were changing the sealed tube volume while keeping the starting materials in stoichiometric ratio and the melt temperature fixed. The key physical consequence of Te overpressure in the 1.2–1.5 MPa pressure range was the reduced hole density and enhanced mobility. Since the topographic and structural integrity and robustness of crystalline surfaces are unaltered, these huge changes in transport give us important information regarding the contribution of surface conduction channels relative to the bulk. In the bulk there are charge carriers donated by intrinsic crystalline lattice defects, such as vacancies and antisites. In Sb2Te3 vacancies on cation (Sb) or anion (Te) sites respectively act as electron donors and acceptors. From the detailed studies of these materials17,50 we know that growth conditions using stoichiometric ratio starting materials result in slightly Te poor crystals, Sb2Te3–x with x≈0.03–0.05. Also, native concentrations of Sb antisites (contributing one hole each) and Te vacancies (contributing two electrons each) are ∼1020 cm−3 and 2 × 1019cm−3, respectively, consistently accounting for the observed Hall number and other material properties17,18. As Te pressure during the growth is increased, a fully stoichiometric (2:3) crystalline material is obtained in which bulk carrier density is the lowest. Under the growth conditions with Te pressure exceeding ∼1.5 MPa, the process is reversed since as the system becomes slightly Te rich (or Sb poor), the antisite defects delivering holes to the bulk are less likely to form and the hole density is increased again. This change in stoichiometry is very slight and transport is the best way to detect it. We note that such fine-tuned non-monotonic doping is not unprecedented; it has been also observed in Sb2Te3 doped with Cr (ref. 17), in molecular-beam grown epitaxial TI films51, and upon stoichiometry variation in Bi–Sb–Te system grown by zone melting52.

Structural characterization and elemental analysis

The structure and composition of crystals grown in the 0.4–3 MPa pressure range was determined from X-ray diffraction and glow discharge analysis (Evans Analytical Group) that determined impurity content (< 0.6 p.p.m. wt) of the final crystals (Supplementary Table 1). X-ray diffraction (Supplementary Fig. 1a) was performed in Panalytical diffractometer using Cu

line from Philips high intensity ceramic sealed tube (3 kW) X-ray source with a Soller slit (0.04 rad) incident and diffracted beam optics. Structural identity was confirmed by micro-Raman spectroscopy of characteristic phonon modes (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

line from Philips high intensity ceramic sealed tube (3 kW) X-ray source with a Soller slit (0.04 rad) incident and diffracted beam optics. Structural identity was confirmed by micro-Raman spectroscopy of characteristic phonon modes (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

Scanning tunneling spectroscopy measurements

STM and STS measurements were carried out in a homebuilt cryogenic UHV STM at a temperature of 4.8 K (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 1). STM studies were performed on five samples. Spectroscopy measurements were performed using a lock-in amplifier running at a frequency of 1.831 kHz and an excitation voltage of 0.2 mV. Spectroscopic imaging was carried out on five samples over a grid of points (either 128 × 128 or 256 × 256 pixels) at various energies using the same lock-in amplifier parameters. Fourier transforms are affine transformed to correct for drift and then hexagonally averaged to enhance signal to noise.

Transport and susceptibility measurements

Transport and susceptibility measurements were performed in a 14 T Quantum Design PPMS system in 1 mT of He gas. For transport measurements, lithographically patterned Au/Ti contacts in Hall bar and van der Pauw geometries were fabricated on 100–300-nm thin crystals exfoliated onto SiO2/Si substrates. The typical uncertainty in transport measurements was ∼0.1%. Out of seven samples three exhibited zero field resistive transition with Tc∼9 K. Two were used for mapping the H versus T phase diagram in Fig. 2, two were used for a careful measurement of the high temperature resistive feature near 50 K. Carrier densities were determined from Hall resistivity and dHdA oscillations (Supplementary Table 2). Differential susceptibility was measured in a compensated pickup-coil detection configuration with the excitation/detection coils designed to align with the applied static field20. The measurement uncertainty was <1%. The a.c. excitation amplitude was set at 10−5 T in a frequency range up to 10 kHz. The system was calibrated using paramagnetic Pd standard and superconducting Nb. Susceptibility calibration and measurements of small background contribution are described in ref. 20. d.c. magnetization measurements were performed using Quantum Design SQUID Magnetometer in up to 5.5 T fields. In all magnetic measurements the samples were supported in gelcaps without any substrates. The uncovered huge diamagnetic enhancement for the samples grown in the 1.4–1.5 MPa range was 100% robust and reproducible.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Zhao, L. et al. Emergent surface superconductivity in the topological insulator Sb2Te3. Nat. Commun. 6:8279 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9279 (2015).

References

Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. Superconducting proximity effect and Majorana fermions at the surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 096407 (2008).

Fu, L. & Berg, E. Odd-parity topological superconductors: Theory and application to CuxBi2Se3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 097001 (2010).

Qi, X.-L., Hughes, T., Raghu, S. & Zhang, S.-C. Time-reversal-invariant topological superconductors and superfluids in two and three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 187001 (2009).

Linder, J., Tanaka, Y., Yokoyama, T., Sudbø, A. & Nagaosa, N. Unconventional superconductivity on a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 067001 (2010).

Fu, L., Kane, C. & Mele, E. Topological insulators in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 106803 (2007).

Zhang, H. et al. Topological insulators in Bi2Se3, Bi2Te3, and Sb2Te3 with a single Dirac cone on the surface. Nat. Phys 5, 438–442 (2009).

Chen, Y. L. et al. Experimental realization of a three-dimensional topological insulator, Bi2Te3 . Science 325, 178–181 (2009).

Hsieh, D. et al. A tunable topological insulator in the spin helical Dirac transport regime. Nature 460, 1101–1105 (2009).

Roushan, P. et al. Topological surface states protected from backscattering by chiral spin texture. Nature 460, 1106–1109 (2009).

Nayak, C., Stern, A., Freedman, M. & Das Sarma, S. Non-Abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1083–1159 (2008).

Hor, Y. S. et al. Superconductivity in CuxBi2Se3 and its implications for pairing in the undoped topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 057001 (2010).

Sasaki, S. et al. Topological superconductivity in CuxBi2Se3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 217001 (2011).

Wray, L. A. et al. Observation of topological order in a superconducting doped topological insulator. Nat. Phys 6, 855–859 (2010).

Zhang, J. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity in topological parent compound Bi2Te3 . Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 24–28 (2011).

Zhu, J. et al. Superconductivity in topological insulator Sb2Te3 induced by pressure. Sci. Rep. 3, 2016 (2013).

Horák, J. et al. Defect structure of Sb2–xCrxTe3 single crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 103, 013516–013516 (2008).

Horák, J., Drašar, Č., Novotný, R., Karamazov, S. & Lošt’ák, P. Non-stoichiometry of the crystal lattice of antimony telluride. Phys. Status Solidi. A 149, 549–556 (1995).

Larkin, A. & Varlamov, A. Theory of fluctuations in superconductors Clarendon Press (2005).

Zhao, L. et al. Singular robust room-temperature spin response from topological Dirac fermions. Nat. Mater. 13, 580–585 (2014).

Wołoś, A. et al. Three-dimensional topological insulators Bi2Te3, Bi2Se3, and Bi2Te2Se—a microwave spectroscopy study. AIP Conf. Proc. 1566, 197–198 (2013).

Tinkham, M. Introduction to superconductivity Courier Dover Publications (2012).

Analytis, J. et al. Two-dimensional surface state in the quantum limit of a topological insulator. Nat. Phys 6, 960–964 (2010).

Maniv, T., Zhuravlev, V., Vagner, I. & Wyder, P. Vortex states and quantum magnetic oscillations in conventional type-II superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 867–911 (2001).

Shoenberg, D. Magnetic oscillations in metals Cambridge University Press (1984).

Das, B., Miller, D., Datta, S. & Reifenberger, R. Evidence for spin splitting in InxGa1–xAs/In0.52Al0.48As heterostructures as B→0. Phys. Rev. B 39, 1411–1414 (1989).

Park, K., Beule, C. D. & Partoens, B. The ageing effect in topological insulators: evolution of the surface electronic structure of Bi2Se3 upon K adsorption. New J. Phys. 15, 113031 (2013).

Bahramy, M. S. et al. Emergent quantum confinement at topological insulator surfaces. Nat. Commun 3, 1159 (2012).

Qu, D.-X., Hor, Y. S., Xiong, J., Cava, R. & Ong, N. P. Quantum oscillations and Hall anomaly of surface states in the topological insulator Bi2Te3 . Science 329, 821–824 (2010).

Taskin, A., Segawa, K. & Ando, Y. Oscillatory angular dependence of the magnetoresistance in a topological insulator Bi1–xSbx . Phys. Rev. B 82, 121302(R) (2010).

Kim, D. et al. Surface conduction of topological Dirac electrons in bulk insulating Bi2Se3 . Nat. Phys 8, 459–463 (2012).

Hein, R. A., Francavilla, T. L. & Liebenberg, D. H. Magnetic susceptibility of superconductors and other spin systems Springer Science & Business Media (1991).

Hein, R. ac magnetic susceptibility, Meissner effect, and bulk superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 33, 7539–7549 (1986).

Mansfield, R. The magnetic susceptibility of bismuth telluride. Proc. Phys. Soc 74, 599–603 (1959).

Shoenberg, D. & Uddin, M. The magnetic properties of bismuth. I. Dependence of susceptibility on temperature and addition of other elements. Proc. R. Soc. A 156, 687–701 (1936).

Otake, S., Momiuchi, M. & Matsuno, N. Temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility of bismuth. J. Phys. Soc. Jap 49, 1824–1828 (1980).

Ganguli, N. & Krishnan, K. The magnetic and other properties of the free electrons in graphite. Proc. R. Soc. A 177, 168–182 (1941).

Eley, S., Gopalakrishnan, S., Goldbart, P. & Mason, N. Approaching zero-temperature metallic states in mesoscopic superconductor-normal-superconductor arrays. Nat. Phys 8, 59–62 (2011).

Han, Z. et al. Collapse of superconductivity in a hybrid tin-graphene josephson junction array. Nat. Phys 10, 380–386 (2014).

Beloborodov, I. S., Lopatin, A. V., Vinokur, V. M. & Efetov, K. B. Granular electronic systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 469–518 (2007).

Martin, J. et al. Observation of electron-hole puddles in graphene using a scanning single-electron transistor. Nat. Phys 4, 144–148 (2008).

Hwang, E., Adam, S. & Das Sarma, S. Carrier transport in two-dimensional graphene layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 186806 (2007).

Skinner, B., Chen, T. & Shklovskii, B. Why is the bulk resistivity of topological insulators so small? Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 176801 (2012).

Beidenkopf, H. et al. Spatial fluctuations of helical Dirac fermions on the surface of topological insulators. Nat. Phys 7, 939–943 (2011).

Spivak, B., Oreto, P. & Kivelson, S. Theory of quantum metal to superconductor transitions in highly conducting systems. Phys. Rev. B 77, 214523 (2008).

Gershenson, M. & McLean, W. Magnetic susceptibility of superconducting granular aluminum. J. Low Temp. Phys. 47, 123–136 (1982).

Reyren, N. et al. Superconducting interfaces between insulating oxides. Science 317, 1196–1199 (2007).

Nandkishore, R., Maciejko, J., Huse, D. A. & Sondhi, S. L. Superconductivity of disordered Dirac fermions. Phys. Rev. B 87, 174511 (2013).

Ghosh, G. The Sb-Te (Antimony-Tellurium) System. J. Phase Equil 15, 349–360 (1994).

Draŝar, C., Loŝták, P. & Uher, C. Doping and defect structure of tetradymite-type crystals. J. Electronic Mat 39, 2162–2164 (2010).

Kim, Y. et al. Structural and thermoelectric transport properties of Sb2Te3 thin films grown by molecular beam epitaxy. J. Appl. Phys. 91, 715–718 (2002).

Kavei, G. & Karami, M. Fabrication and characterization of the p-type (Bi2Te3)x(Sb2Te3)1x . Bull. Mater. Sci. 29, 659–663 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to David Huse, Steven Kivelson, Boris Spivak, Kyungwha Park, Kamran Behnia, Steven Girvin, Shivaji Sondhi and Alexander Gurevich for enlightening discussions. V.O. wishes to acknowledge stimulating discussions with Jeremy Levy and Sarang Gopalakrishnan. We thank Jeff Secor for the technical assistance with Raman spectroscopy. This work was supported in part by NSF under DMR-1122594 (L.K.-E.), DMR-1420634 (A.P., L.K.-E. and V.O.), DMR-1322483 (L.K.-E.), DMR-0955714 (V.O.), and by DOD-W911NF-13-1-0159 (L.K.-E.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Experiments were designed by L.K.-E. and L.Z. L.Z. and H.D. carried out the growth of the single crystals, I.K. and Z.C. provided structural and chemical characterization, and H.D, L.Z. and M.B. designed and fabricated exfoliated structures with lithographic contacts. Transport and magnetic measurements were performed by L.Z. and H.D., STS and STM experiments were performed by E.A., E.R. and A.P., and data analysis was done by L.Z., V.O. and L.K.-E. All authors discussed the results, and V.O., L.Z. and L.K.-E. contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-9, Supplementary Tables 1-2, Supplementary Notes 1-5 and Supplementary References (PDF 1369 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, L., Deng, H., Korzhovska, I. et al. Emergent surface superconductivity in the topological insulator Sb2Te3. Nat Commun 6, 8279 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9279

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9279

This article is cited by

-

Cluster-assembled superatomic crystals for chirality-dependent charge-to-spin conversion

npj Quantum Materials (2023)

-

Superconductivity in a ferroelectric-like topological semimetal SrAuBi

npj Quantum Materials (2023)

-

Dirac lines and loop at the Fermi level in the time-reversal symmetry breaking superconductor LaNiGa2

Communications Physics (2022)

-

The pressure-enhanced superconducting phase of Sr\(_x\)–Bi\(_2\)Se\(_3\) probed by hard point contact spectroscopy

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Absence of emergent supersymmetry at superconducting quantum critical points in Dirac and Weyl semimetals

npj Quantum Materials (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.