Abstract

Breast-fed children, compared with the bottle-fed ones, have a lower incidence of acute gastroenteritis due to the presence of several antiinfective factors in human milk. The aim of this work is to study the ability of human milk oligosaccharides to prevent infections related to some common pathogenic bacteria. Oligosaccharides of human milk were fractionated by gel-filtration and characterized by thin-layer chromatography and high-performance anion exchange chromatography. Fractions obtained contained, respectively, 1) acidic oligosaccharides, 2) neutral high-molecular-weight oligosaccharides, and 3) neutral low-molecular-weight oligosaccharides. Experiments were carried out to study the ability of oligosaccharides in inhibiting the adhesion of three intestinal microorganisms (enteropathogenic Escherichia coli serotype O119, Vibrio cholerae, and Salmonella fyris) to differentiated Caco-2 cells. The study showed that the acidic fraction had an antiadhesive effect on the all three pathogenic strains studied (with different degrees of inhibition). The neutral high-molecular-weight fraction significantly inhibited the adhesion of E. coli O119 and V. cholerae, but not that of S. fyris; the neutral low-molecular-weight fraction was effective toward E. coli O119 and S. fyris but not V. cholerae. Our results demonstrate that human milk oligosaccharides inhibit the adhesion to epithelial cells not only of common pathogens like E. coli but also for the first time of other aggressive bacteria as V. cholerae and S. fyris. Consequently, oligosaccharides are one of the important defensive factors contained in human milk against acute diarrheal infections of breast-fed infants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Infectious diarrheal diseases constitute a leading cause of infant morbidity not only in developing countries but also in developed areas (1). In fact, in the United States, acute diarrhea represents an important cause of childhood morbidity, especially during the first years of life, determining an economical loss that has been estimated in the order of several millions of dollars (2).

In infants, infections of the gastrointestinal tract are caused by a wide variety of enteropathogens, including bacteria, viruses, and parasites. There is now strong evidence supporting a relationship between breast-feeding and a lower incidence in diarrhea. Breast-feeding offers protection with different mechanisms against diarrhea due to several antiinfective substances present in human milk, such as secretory antibodies, lactoferrin, lysozyme, etc. (3–5).

In the last 15 y, evidence has also emerged on the protective role of another group of substances, oligosaccharides (6–8). They are synthesized in a large number by specific glycosyltransferases present in the mammary gland through the sequential addition to lactose of fucose, galactose, N-acetylglucosamine, and sialic acid. Each single oligosaccharide varies dynamically during the different phases of lactation (9). From the quantitative point of view, oligosaccharides, all together, represent the third component of human milk, besides lactose and lipids (10, 11).

Breast-fed infants ingest daily several grams of oligosaccharides and these substances have been found in feces in large quantities (12–14). It follows that most oligosaccharides contained in human milk are not digested by intestinal enzymes, and so are present in large quantity both in the small and large intestine of neonates (15, 16).

It is well known that viruses, bacteria, or toxins develop their pathogenic effect through the adhesion to receptors located on the cells of the epithelial surface. Numerous receptors are glycan chains of glycoproteins and glycolipids of the intestinal cell membranes, and human milk oligosaccharides may compete with these receptors in binding pathogenic agents, hindering their adhesion as well as the subsequent pathologic process (7, 8, 17).

So far, the antiadhesive effect of human milk oligosaccharides has been described only for a few bacteria (18–20). We present the results of experiments carried out in vitro on the effect of human milk oligosaccharides in inhibiting the adhesion to Caco-2 cells of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholerae, and Salmonella fyris pathogen bacteria of diarrhea in infancy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human milk oligosaccharide fractions.

The adhesion/inhibition tests were performed using human milk oligosaccharide fractions prepared in our laboratory (21). Briefly, a 1000-mL pool of human colostrum was obtained by mixing several samples collected four days after delivery and stored at –80°C until use. Oligosaccharides were isolated according to Kobata et al. (22) and fractionated by gel filtration (23). The effluent from a BioGel P-4 column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was collected in 5.0-mL aliquots. Each of them was characterized by thin-layer chromatography (21) and those with similar pattern were combined, lyophilized, and labeled as fractions A to G on the basis of their different composition. Each fraction was analyzed for total sugar (24) and sialic acid content (25) and characterized by high performance anion exchange chromatography (21). Milk purified oligosaccharides (from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO; Bio Carb, Lund, Sweden; and Dextra Laboratories Ltd., Reading, UK) were used both as internal and external standards for the identification of the peaks (9). To use samples with different compositions among all fractions, we chose for our experiments the following: A (acidic fraction: sialyl-oligosaccharides) (Fig. 1A); D (neutral fraction: penta-octasaccharides (Fig. 1B); F2 (neutral fraction: tri-pentasaccharides and lactose) (Fig. 1C). A pool, made up by mixing each fraction (A to G) with weight ratio 1:1, was also used.

(A) High-performance anion exchange chromatography (HPAEC) of 1 mg/mL solution of fraction A; major peaks with the concentration expressed as mg/mL (in parenthesis): 1) N-acetyl-neuraminic acid (0.005); 2) monofucosyl-monosialyllacto-N-neohexaose (0.032); 3) monosialyl-monofucosyllacto-N-tetraose (0.015); 4) monofucosyl-monosialyllacto-N-hexaose (0.018); 5) sialyllacto-N-neotetraose (c) (0.072); 6) 6′-sialyllactose (0.045); 7) sialyllacto-N-tetraose (a) (0.025); 8) 3′-sialyllactose (0.015); 9) sialyllacto-N-tetraose (b) (0.025); 10) disialyllacto-N-tetraose (0.059). (B) HPAEC of fraction D: 1) difucosyllacto-N-hexaose II (0.028); 2) difucosyllacto-N-hexaose I (0.035); 3) lacto-N-fucopentaose III (0.044); 4) lacto-N-fucopentaose II (0.040); 5) lacto-N-fucopentaose I (0.159); 6) monofucosyllacto-N-hexaose II (0.056); 7) lacto-N-neotetraose (0.072); 8) lacto-N-neohexaose (0.008); 9) lacto-N-tetraose (0.083); 10) lacto-N-hexaose (0.006). (C) HPAEC of fraction F2: 1) 3-fucosyllactose (0.034); 2) lactodifucotetraose (0.032); 3) lactose (0.592); 4) 2′-fucosyllactose (0.264).

Oligosaccharide and monosaccharide standards.

Purified oligosaccharide and monosaccharide standards were also used in the adhesion/inhibition tests: a) acidic oligosaccharides: 3′-SL and 6′-SL; b) neutral oligosaccharides: 3-FL, 2′-FL, and lactodifucotetraose; c) monosaccharides: glucose, galactose, sialic acid, N-acetylglucosamine, fucose.

Bacteria and culture conditions.

Three bacterial strains were used throughout this study. They included V. cholerae ATCC 14034 (O1 classical strain, Inaba serotype) and two strains isolated from infants with diarrhea in Italy—an enteropathogenic (EPEC) serotype O119 E. coli strain previously described by The Italian Study Group on Gastrointestinal Infections (26) and S. fyris (serotype 4,12:1, v,4,2), an uncommon group B Salmonella serotype for which the mechanisms of pathogenicity are uncharacterized, isolated during a small outbreak of diarrhea (unpublished data). Brain heart infusion (BHI) and Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) were used for routine growth of bacteria.

Cell line.

The human colon carcinoma cell line Caco-2 (ATCC HTB37) (27) derives from a relatively well-differentiated tumor and grows slowly in nude mice; when seeded on either permeable filters or impermeable substrates at high density, Caco-2 cells consistently form well-polarized monolayers joined by tight junction. In postconfluent cultures, monolayers exhibit structural and functional differentiation patterns characteristic of mature enterocytes in which the cell layer is covered with brush border microvilli, simulating intestinal cells (28).

Caco-2 cells were routinely grown in 25 cm2 plastic tissue culture flasks (Corning Costar, Milan, Italy) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% (vol/vol) CO2 in air. The culture medium was Dulbecco's modified Eagle minimum essential medium (DMEM), containing 25 mM glucose, 4 mM l-glutamine, 3.7 mg sodium bicarbonate (Euroclone, West York, U.K.) per mL, with 1% (vol/vol) nonessential amino acids and supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum (Euroclone).

Confluent cell monolayers were trypsinized and adjusted to a concentration of 2.5 × 105 cells/mL in culture medium; 1 mL cell suspension was dispensed into each 22-mm well of a 12-well tissue culture plate (Corning Costar, Milan, Italy) and incubated to obtain, 4 d later, semiconfluent monolayers and, after 15 more days, postconfluent monolayers.

Infection of Caco-2 cells and recovery of adherent bacteria.

Infections were performed at different incubation times on the basis of previous reported data (29–32). Briefly, after overnight growth at 37°C in BHI broth (E. coli and S. fyris) and LB broth (V. cholerae), bacterial cells were either subcultured in BHI broth and incubated in a shaker at 37°C for 2 h (S. fyris and V. cholerae) and then harvested by centrifugation at 5000 rpm or were directly harvested by centrifugation (E. coli). Bacterial cells were resuspended in PBS to OD540 0.6 ± 0.02 and diluted in DMEM. Then, 0.5 mL inoculum (∼1 × 108 CFU/mL) was added to confluent monolayers.

After 30 min (V. cholerae), 90 min (E. coli), or 120 min (S. fyris) of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, cells were washed three times with PBS to remove nonadherent bacteria and then lysed in Triton X-100 (0.1% in cold sterile water) to release adherent bacteria. CFU of bacteria were counted by plating suitable dilutions of the lysates on BHI or LB agar and incubating for 36–48 h at 37°C. Results were expressed as percentages of the initial inoculum.

Bacteria associated with Caco-2 monolayers were also evaluated by Gram staining. Stained monolayers grown on slides (SlideFlask, Nunc GmbH & Co., Weisbaden, Germany) were examined microscopically. The percentage of Caco-2 cells with associated bacteria was determined by counting all Caco-2 cells in 10 random microscopic areas: a positive result was scored when there was at least one bacterial cell per Caco-2 cell. The number of cell-associated bacteria was determined by examining 100 cells.

Infection inhibition studies.

In inhibition experiments, Fraction A, Fraction D, Fraction F2, and the pool of milk oligosaccharides were used; lactose and monosaccharides (glucose, galactose, sialic acid, N-acetylglucosamine, fucose), which are components of oligosaccharide molecules, were also tested.

Confluent monolayers were washed three times with DMEM, covered with 250 μL of DMEM containing oligosaccharides (pool, fractions, or purified standards) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The concentration of both pool and fraction oligosaccharides was 1, 5, and 10 mg/mL. Single purified standards were used at the concentrations found in human milk of the most common genotype mothers (active Secretor and Lewis genes): 2′-FL = 2.5 mg/mL; 3-FL = 0.5 mg/mL; lactodifucotetraose = 0.5 mg/mL; 3′-SL = 0.1 mg/mL 6′-SL = 0.3 mg/mL (6, 9, 33). At the end of the incubation period, 250 μL bacterial inoculum (approx. 2 × 108 CFU/mL) was added. After different times of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, cells were washed three times with PBS and adherent bacteria were recovered as described above.

Adhesion inhibition experiments were performed by assessing the rate of recovery of adherent bacteria from infected Caco-2 cells. Before infection, cell monolayers were separately incubated with lactose, monosaccharides (glucose, galactose, sialic acid, N-acetylglucosamine, fucose), the pool, the A, D, and F2 fractions, and 3′-SL, 6′-SL, 3-FL, DFL, and 2′-FL standards.

Statistical analysis.

All experiments were performed as three or five independent assays. Assays were performed in triplicate per experimental run. The percentage of inhibition was calculated by the equation: (control – test)/control × 100. Results were expressed as mean value and 95% confidence interval (CI).

RESULTS

In the absence of oligosaccharides, bacteria associated with Caco-2 monolayers were evaluated by determining CFU per milliliter and by microscopic examination of Gram-stained monolayers. Counts of CFU indicated that bacteria associated with the monolayers ranged from 14.9% (V. cholerae) to 32.1% (E. coli) and 23.4% (S. fyris). In Gram-stained preparations, approximately 50% of Caco-2 cells with associated bacteria were observed (Figs. 2a and 3a).

The results of inhibition experiments are reported in Table 1. Each single monosaccharide tested (glucose, galactose, sialic acid, N-acetylglucosamine, fucose), which human milk oligosaccharides are made up of, did not significantly inhibit the adhesion to Caco-2 cells of any of the three tested strains; in fact, their percentage of inhibition ranged from –3.1 to 6.25.

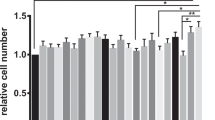

Oligosaccharides as a whole (pool) were effective in inhibiting the adhesion of V. cholerae and E. coli O119, but not of S. fyris. As for the inhibition effect of the different fractions tested, E. coli O119 was significantly inhibited by all fractions, acidic (A) as well as neutral (D, F2) (Fig. 2); between acidic oligosaccharide standards, 3′-SL showed the highest degree of inhibition, whereas among neutral oligosaccharides, only 3-FL was effective.

Also, S. fyris was inhibited by the acid fraction (A) as well as by the neutral one (F2) (Fig. 3), essentially made up of low-molecular-weight oligosaccharides and lactose; whereas the neutral high-molecular-weight fraction (D) and pool did not show any inhibitory capacity. Among the acid and neutral low-molecular-weight oligosaccharide standards, only 6′-SL and 3-FL showed a limited percentage of inhibition.

The neutral high-molecular-weight fraction D was effective in inhibiting adhesion of V. cholerae, whereas a lower inhibition was obtained by the acid fraction (A) on the same pathogen.

It must be pointed out that none of the low-molecular-weight oligosaccharides (fraction F2 and five purified standards) showed an inhibitory effect on V. cholerae.

Moreover, the analysis of the results shows that the acid fraction A had an antiadhesive effect on the three pathogenic strains studied (with different degrees of inhibition). On the contrary, the neutral high-molecular-weight fraction D significantly inhibited the adhesion of E. coli O119 and V. cholerae but not that of S. fyris; whereas the neutral low-molecular-weight fraction F2 was effective toward E. coli O119 and S. fyris but not V. cholerae.

DISCUSSION

The adhesion of a bacterium to the host cell is the basic requirement to carry on the pathogenic effect. The overall process of binding involves the meeting of a solvated polyhydroxylated glycan placed on the surface of cells, with a solvated protein-combining site (adhesin) present on the pathogenic agent; the forces involved in this link are represented by hydrogen binding, Van der Walls interactions, and charge and dipole attraction (34, 35), suggesting that if a surface on the glycan is complementary to the protein-combining site, water can be displaced and binding occurs. Most combining sites of adhesins interact with oligosaccharides, mainly made of up to 5 monosaccharidic units (8). Usually, adhesion takes place with the nonreducing end of the oligosaccharidic chain, even though different adhesins can interact with sugars placed in more internal positions of molecules (36). As a consequence, the affinity between a pathogenic agent and the cell receptor is the result of a multiple interaction.

Receptors present on the surface are made up of oligosaccharidic residues of glycoproteins and glycolipids of cell membranes. The adhesion to such receptors can be inhibited or reduced by the presence of free oligosaccharides with a structure analogous to that of cell receptors, so that the pathogenic agent binds with them and not with the cell membrane, with a reduction of pathogenic effect as a consequence (8).

It has been proved that also human milk oligosaccharides have a protective effect, based on the same mechanism. Such effect was observed on viruses and toxins as well as on bacteria (7, 8, 36, 37). In particular, as regards the capacity of human milk oligosaccharides to inhibit adhesion of pathogenic germs, data available up to now concern few bacteria only (Streptococcus pneumoniae, E. coli, Helicobacter pylori, Campylobacter jejuni, Listeria monocytogenes) responsible for infections at the expense of respiratory, digestive, and urinary systems. As for S. pneumoniae, Anderson et al. (18) proved in 1986 that lacto-N-tetraose (LNT) and lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT) can inhibit the adhesion to buccal epithelial cells. The same positive effect of LNnT was also confirmed on lung tumoral cells and animal models (38). On the contrary, Barthelson et al. (39), using conjunctival cells, observed a reduced effectiveness of LNnT in inhibiting some Streptococcus strains, while its 6′ sialyl-derivative was very effective. Hence, it may be stated that Streptococcus can be inhibited in different conditions both by neutral and acid oligosaccharides.

Data available so far about the activity of human milk oligosaccharides toward E. coli concern both enteropathogenic and uropathogenic strains. Coppa et al. (40) observed that a mixture of neutral oligosaccharides, mainly tri-tetrasaccharides, inhibited the adhesion of uropathogenic E. coli to human uro-epithelial cells, while, as far as enteropathogenic E. coli is concerned, Cravioto et al. (19) showed that fucosyl-tetra-pentasaccharides were able to inhibit its adhesion to HEp-2 cells. Our present study confirms the capacity of fucosyl-oligosaccharides containing fractions (D, F2) to inhibit the adhesion of enteropathogenic E. coli O119; in addition, 3-FL, among neutral low-molecular-weight oligosaccharides, acidic oligosaccharides in toto (A fraction), 3′-SL, and 6′-SL were also able to reduce adhesion. The difference between the data observed by Cravioto et al. (19) and ours may be due to different systems used both for the strains of enteropathogenic E. coli and the types of cells.

Recently, further pathogenic agents have been reported toward which human milk oligosaccharides are effective as antiadhesive agents; in particular, by using different epithelial cell lines, adhesion of H. pylori was inhibited by sialyl-oligosaccharides, mainly 3′-SL. The effectiveness of such oligosaccharides on H. pylori was also confirmed by using animal models (rhesus monkeys) (41).

Two more bacteria were studied to evaluate the effect of human milk oligosaccharides: L. monocytogenes and C. jejuni. The adhesion of L. monocytogenes to Caco-2 was inhibited by neutral high- and low-molecular-weight oligosaccharides (mostly fucosylated) (21) and that of C. jejuni was inhibited by fucosyl-oligosaccharides, using both in vitro and in vivo systems (42).

Data reported in this work are the first about the effect of human milk oligosaccharides on S. fyris and V. cholerae strains and show that the antiadhesive effect on S. fyris—even though rather weak—was obtained by acid and neutral low-molecular-weight oligosaccharides, whereas inhibition on V. cholerae took place mainly in the presence of neutral high-molecular-weight oligosaccharides.

It may hence be inferred that human milk oligosaccharides on the whole are effective in inhibiting adhesion of the different pathogenic agents to receptors of epithelial cells. This is to be related to the fact that bacterial adhesins are numerous and structurally different as well as to the receptors present on the epithelial cell surface. Therefore the germ/host cell adhesion is the result of a multiple interaction and a high binding affinity through a joint action of several receptors (“Velcro effect”) (8, 36). Actually, when considered separately, oligosaccharides may have a weak bond, whereas they have an especially strong bond as a whole. This could explain the different percentage of inhibition observed in the different pathogenic strains, depending on oligosaccharides tested. In fact, it must be considered that each fraction studied is made up of a mixture of oligosaccharides, and if it was possible to carry on tests using few specific pure standards of acidic or neutral low-molecular-weight oligosaccharides, it was not possible to determine the efficacy of the remaining oligosaccharides contained in the mixture. On the contrary, each fraction tested, made up of a mixture of several oligosaccharides, was effective on the various pathogens, even though with different degrees of intensity. For example, D-fraction (made up of neutral fucosylated high-molecular-weight oligosaccharides) was able to inhibit both enteropathogenic E. coli O119 and V. cholerae; on the other hand, from the literature, it appears that fucosylated oligosaccharides have always been effective on C. jejuni (19). L. monocytogenes (21), and another strain of enteropathogenic E. coli (30). Such phenomenon could be explained by the fact that the mixture is made up of oligosaccharides, separately acting on different specific receptors. This proves also that a microorganism has a share of adhesins similar to those of another germ, and, therefore, both have common oligosaccharidic receptors. This explains why one single oligosaccharide contained in human milk can—at least to some extent—inhibit the adhesion of several pathogenic germs, as our tests showed for 3-FL toward E. coli O119 and S. fyris. We therefore believe that the protective effect of human milk oligosaccharides is not due to the action of single oligosaccharides acting on single bonds but is the result of the contemporary and joint action of several oligosaccharides that can act on various bonds, both of one single germ and different germs, considering also that a high-molecular-weight oligosaccharide with a branched structure can have several bond sites with one single adhesin. Moreover, a careful analysis of the structure of the nonreducing ends of oligosaccharides, used in our experiment, shows a very heterogeneous monosaccharide composition; therefore, it is impossible to identify a specific monosaccharide sequence able to inhibit the adhesion.

In conclusion, the literature and our own results make it possible to assert that human milk oligosaccharides can carry on a protective role toward the most common intestinal infections of breast-fed newborns and infants (43). These results may represent a stimulus to further research such as in vivo and/or ex vivo studies, as recently carried out by Ruiz-Palacios et al. (42).

Oligosaccharides, then, enter the complex defence system made up of various substances and mechanisms protecting breast-fed infants against infections. It follows that there are further reasons to recommend prolonged breast-feeding, mainly in developing countries where intestinal infections are still a significant cause of morbidity and mortality.

Abbreviations

- BHI:

-

brain heart infusion

- CFU:

-

colony forming units

- 2′-FL:

-

2′-fucosyllactose

- 3-FL:

-

3-fucosyllactose

- 3′-SL:

-

3′-sialyllactose

- 6′-SL:

-

6′-sialyllactose

References

Gracey M 1997 Diarrheal disease in perspective. In: Gracey M, Walker-Smith JA (eds) Diarrheal Disease. Nestlè Nutrition Workshop Series. Volume 38. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, pp 1–8

Avendano P, Matson DO, Long J, Whitney S, Matson CC, Pickering LK 1993 Costs associated with office visits for diarrhea in infants and toddlers. Pediatr Infect Dis J 12: 897–902

Howie PW, Forsyth JS, Ogston SA, Clark A, Florey CD 1990 Protective effect of breast feeding against infection. BMJ 300: 11–16

Morrow AL, Guerrero ML, Shults J, Calva JJ, Lutter C, Bravo J, Ruiz-Palacios G, Morrow RC, Butterfoss FD 1999 Efficacy of home- based peer counselling to promote exclusive breastfeeding: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 353: 1226–1231

WHO Collaborative Study Team on the Role of Breastfeeding on the Prevention of Infant Mortality 2000 Effect of breastfeeding on infant and child mortality due to infectious diseases in less developed countries: a pooled analysis. Lancet 355: 451–455

Kunz C, Rudloff S 1993 Biological functions of oligosaccharides in human milk. Acta Paediatr 82: 903–912

Newburg DS 2000 Oligosaccharides in human milk and bacterial colonization. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 30: S8–S17

Zopf D, Roth S 1996 Oligosaccharide anti-infective agents. Lancet 347: 1017–1021

Coppa GV, Pierani P, Zampini L, Carloni I, Carlucci A, Gabrielli O 1999 Oligosaccharides in human milk during different phases of lactation. Acta Paediatr 88: 89–94

Coppa GV, Gabrielli O, Pierani P, Catassi C, Carlucci A, Giorgi PL 1993 Changes in carbohydrate composition in human milk over 4 months of lactation. Pediatrics 91: 637–641

Viverge D, Grimmonprez L, Cassanas G, Bardet L, Bonnet H, Solere M 1985 Variations of lactose and oligosaccharides in milk from women of blood types secretor A or H, secretorLewis and Secretor H/nonsecretor Lewis during the course of lactation. Ann Nutr Metab 29: 1–11

Chaturvedi P, Warren CD, Buescher CR, Pickering LK, Newburg DS 2001 Survival of human milk oligosaccharides in the intestine of infants. Adv Exp Med Biol 501: 315–323

Coppa GV, Pierani P, Zampini L, Bruni S, Carloni I, Gabrielli O 2001 Characterization of oligosaccharides in milk and feces of breast-fed infants by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography. Adv Exp Med Biol 501: 307–314

Kunz C, Rudloff S, Baier W, Klein N, Strobel S 2000 Oligosaccharides in human milk: structural, functional and metabolic aspects. Annu Rev Nutr 20: 699–722

Engfer MB, Stahl B, Finke B, Sawatzki G, Daniel H 2000 Human milk oligosaccharides are resistant to enzymatic hydrolysis in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Am J Clin Nutr 71: 1589–1596

Gnoth MJ, Kunz C, Kinne-Saffran E, Rudloff S 2000 Human milk oligosaccharides are minimally digested in vitro. J Nutr 130: 3014–3020

Ofek I, Sharon N 1990 Adhesins as lectins: specificity and role in infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 151: 91–114

Andersson B, Porras O, Hanson LA, Lagergard T, Svanborg-Eden C 1986 Inhibition of attachment of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae by human milk and receptor oligosaccharides. J Infect Dis 153: 232–237

Cravioto A, Tello A, Villafan H, Ruiz J, del Vedovo S, Neeser JR 1991 Inhibition of localized adhesion of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to HEp-2 cells by immunoglobulin and oligosaccharides fractions of human colostrum and breast milk. J Infect Dis 163: 1247–1255

Simon PM, Goode PL, Mobasseri A, Zopf D 1997 Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori binding to gastrointestinal epithelial cells by sialic acid-containing oligosaccharides. Infect Immun 65: 750–757

Coppa GV, Bruni S, Zampini L, Galeazzi T, Facinelli R, Capretti R, Carlucci A, Gabrielli O 2003 Oligosaccharides of human milk inhibit the adhesion of listeria monocytogenes to Caco 2 cells. Ital J Pediatr 29: 61–68

Kobata A, Yamashita K, Tachibana Y 1978 Isolation of oligosaccharides from human milk. Methods Enzymol 28: 262–271

Yamashita K, Mizuochi T, Kobata A 1982 Analysis of oligosaccharides by gel filtration. Methods Enzymol 83: 105–126

Dubois M, Gilles AK, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F 1956 Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Ann Chem 28: 350–356

Warren L 1959 The thiobarbituric acid assay of sialic acids. J Biol Chem 234: 1971–1975

Caprioli A, Pezzella C, Morelli R, Giammanco A, Arista S, Crotti D, Facchini M, Guglielmetti P, Piersimoni C, Luzzi I 1996 Enteropathogens associated with childhood diarrhea in Italy. The Italian Study Group on Gastrointestinal Infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J 15: 876–883

Rousset M 1986 The human colon carcinoma cell lines HT-29 and Caco-2: two in vitro models for the study of intestinal differentiation. Biochimie 68: 1035–1040

Chantret I, Barbat A, Dussaulx E, Brattain MG, Zweibaum A 1988 Epithelial polarity, villin expression and enterocytic differentiation of cultured human colon carcinoma cells: a survey of twenty cell lines. Cancer Res 48: 1936–1941

Giannasca KT, Giannasca PJ, Neutra MR 1996 Adherence of Salmonella typhimurium to Caco-2 cells: identification of a glycoconjugate receptor. Infect Immun 64: 135–145

Kerneis S, Bilge SS, Fourel V, Chauviere G, Coconnier MH, Servin AL 1991 Use of purified F1845 fimbrial adhesin to study localization and expression of receptors for diffusely adhering Escherichia coli during enterocytic differentiation of human colon carcinoma cell lines HT-29 and Caco-2 in culture. Infect Immun 59: 4013–4018

Panigrahi P, Tall BD, Russell RG, Detolla LJ, Morris JG Jr 1990 Development of an in vitro model for study of non-01 Vibrio cholerae virulence using Caco-2 cells. Infect Immun 58: 3415–3424

Sperandio V, Giron JA, Silveira WD, Kaper JB 1995 The OmpU outer membrane protein, a potential adherence factor of Vibrio cholerae.. Infect Immun 63: 4433–4438

Erney RM, Malone WT, Skelding MB, Marcon AA, Kleman-Leyer KM, O'Ryan ML, Ruiz-Palacios G, Hilty MD, Pickering LK, Prieto PA 2000 Variability of human milk neutral oligosaccharides in a diverse population. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 30: 182–192

Lemieux RU 1996 How water provides the impetus for molecular recognition in aqueous solution. Acc Chem Res 29: 373–380

Varki A, Cummings R, Esko J, Freeze H, Hart G, Marth J 1999 Protein-glycan interaction. In: Varki A, Cummings R, Esko J, Freeze H, Hart G, Marth J (eds) Essentials of Glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp 41–56

Karlsson KA 1998 Meaning and therapeutic potential of microbial recognition of host glycoconjugates. Mol Microbiol 29: 1–11

Newburg DS 2003 Do breastfeeding mothers provide innate immunity to their infants through milk oligosaccharides?. Ital J Pediatr 29: 6–8

Idanpaan-Heikkila I, Simon PM, Zopf D, Vullo T, Cahill P, Sokol K, Tuomanen E 1997 Oligosaccharides interfere with the establishment and progression of experimental pneumococcal pneumonia. J Infect Dis 176: 704–712

Barthelson R, Mobasseri A, Zopf D, Simon P 1998 Adherence of Streptococcus pneumoniae to respiratory epithelial cells is inhibited by sialylated oligosaccharides. Infect Immun 66: 1439–1444

Coppa GV, Gabrielli O, Giorgi P, Catassi C, Montanari MP, Varaldo PE, Nichols BL 1990 Preliminary study of breastfeeding and bacterial adhesion to uroepithelial cells. Lancet 335: 569–571

Mysore JV, Wigginton T, Simon PM, Zopf D, Heman-Ackah LM, Dubois A 1999 Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in rhesus monkeys using a novel antiadhesion compound. Gastroenterology 117: 1316–1325

Ruiz-Palacios GM, Cervantes LE, Ramos P, Chavez-Munguia B, Newburg DS 2003 Campylobacter jejuni binds intestinal H (O) antigen (Fuc a1, 2Gal b1, 4GlcNAc), and fucosyloligosaccharides of human milk inhibit its binding and infection. J Biol Chem 278: 14112–14120

Sharon N, Ofek I 2000 Safe as mother's milk: carbohydrates as future anti-adhesion drugs for bacterial diseases. Glycoconj J 17: 659–664

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coppa, G., Zampini, L., Galeazzi, T. et al. Human Milk Oligosaccharides Inhibit the Adhesion to Caco-2 Cells of Diarrheal Pathogens: Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholerae, and Salmonella fyris. Pediatr Res 59, 377–382 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1203/01.pdr.0000200805.45593.17

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/01.pdr.0000200805.45593.17

This article is cited by

-

A bacterial autotransporter impairs innate immune responses by targeting the transcription factor TFE3

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Biofilm formation under high temperature causes the commensal bacteria Bacillus cereus WPySW2 to shift from friend to foe in Neoporphyra haitanensis in vitro model

Journal of Oceanology and Limnology (2023)

-

Supplementation of oligosaccharide-based polymer enhanced growth and disease resistance of weaned pigs by modulating intestinal integrity and systemic immunity

Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology (2022)

-

Role of milk carbohydrates in intestinal health of nursery pigs: a review

Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology (2022)

-

Evidence-Based Approaches to Minimize the Risk of Developing Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Premature Infants

Current Treatment Options in Pediatrics (2022)