Abstract

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is responsible for maintaining blood pressure and vascular tone. Modulation of the RAAS, therefore, interferes with essential cellular processes and leads to high blood pressure, oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis, and hypertrophy. Consequently, these conditions cause fatal cardiovascular and renal complications. Thus, the primary purpose of hypertension treatment is to diminish or inhibit overactivated RAAS. Currently available RAAS inhibitors have proven effective in reducing blood pressure; however, beyond hypertension, they have failed to treat end-target organ injury. In addition, RAAS inhibitors have some intolerable adverse effects, such as hyperkalemia and hypotension. These gaps in the available treatment for hypertension require further investigation of the development of safe and effective therapies. Current research is focused on the combination of existing and novel treatments that neutralize the angiotensin II type I (AT1) receptor-mediated action of the angiotensin II peptide. Preclinical studies of peptide- and nonpeptide-based therapeutic agents demonstrate their conspicuous impact on the treatment of cardiovascular diseases in animal models. In this review, we will discuss novel therapeutic agents being developed as RAAS inhibitors that show prominent effects in both preclinical and clinical studies. In addition, we will also highlight the need for improvement in the efficacy of existing drugs in the absence of new prominent antihypertensive drugs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension is a severe medical condition and a significant risk factor for the occurrence of associated cardiovascular and renal ailments [1]. Worldwide, ~1.13 billion people have hypertension, according to 2010 data [2]. In addition to lifestyle factors, several genetic factors have also been linked with hypertension [3, 4]. Despite the availability of diverse treatment strategies, fewer than one in five patients have their blood pressure (BP) under control; hence, the management of hypertension has become an important healthcare goal.

Deregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), which plays a fundamental role in the regulation of BP, is one of the critical reasons for the progression of hypertension (Fig. 1) [5]. The primary role of renin is the cleavage of angiotensinogen to angiotensin I (Ang I), which is then converted to angiotensin II (Ang II) by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) [6]. The physiological effects of Ang II on the RAAS are exerted by its interaction with the Ang II type 1 (AT1) and Ang II type 2 (AT2) receptors. In the classic system, the AT1 receptor has a central role in the progression of hypertension. Ang II, through the AT1 receptor, leads to vasoconstriction, sodium-water retention, inflammation, hypertrophy, fibrosis, and secretion of aldosterone [7]. In addition, Ang II also activates NADPH oxidase, leading to ROS-induced oxidative stress by causing mitochondrial dysfunction [8].

RAAS components involved in hypertension pathophysiology. The natriuretic peptide system plays a beneficial role in the control of hypertension. Bradykinin and natriuretic peptides are potent vasodilatory peptides that help normalize the harmful effects of Ang-II. The vasoconstrictor peptide Ang-II, through the AT1 receptor, leads to harmful effects such as fibrosis, aldosterone secretion and sodium-water retention. However, Ang-II, through the AT2 receptor, counteracts the action of the AT1 receptor. The novel protective axis ACE2/Ang(1–7)/MasR regulates BP and opposes the actions of Ang-II. Downstream ofthe RAAS, aminopeptidase A (APA) and aminopeptidase N (APN) inhibitors also contribute to antihypertensive properties. All vasoactive peptides mediate their physiologic actions through a variety of receptors (AT1R, AT2R, BKR, NPR-A, and MasR). Note: New emerging targets with vasodilator properties are shown in yellow, enzymes are denoted in blue, and the dotted red line indicates inhibition. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1R), angiotensin type 2 receptor (AT2R), angiotensin type 4 receptor (AT4R), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), B-type natriuretic peptide (ANP), Natriuretic peptide receptor-A (NPR-A), Guanylyl cyclase A (GCA), Cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), protein kinase G (PKG), neprilysin (NEP), neprilysin inhibitor (NEPi), aminopeptidase A (APA), aminopeptidase N (APN)

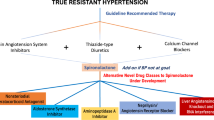

The introduction of RAAS inhibitors in the 1980s was a breakthrough at a time when hypertension and associated diseases were considerable health risks. Several antihypertensive drugs are commercially available that help maintain BP and improve the quality of life of patients with hypertension. In addition, comprehensive remedial approaches are used in the management of cardiovascular and renal diseases. The current hypertension treatment regimen includes diuretics, renin inhibitors, ACE inhibitors, Ang II type 1 receptor blockers (ARBs), beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers and mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) antagonists [9]. These medications principally halt the harmful after-effects of excess Ang II and aldosterone release, which are mediated through AT1 and MR, respectively [10]. However, these drugs, even though they are effective in curing hypertension, have limited ability to prevent end-organ damage. Moreover, inhibition of ACE is insufficient in some cases, as it results in increased Ang I levels and the activation of non-ACE-dependent pathways that convert Ang I to Ang II [11]. In addition, ARBs increase plasma renin activity (PRA), which in turn increases Ang II levels and thus results in competition between Ang II and ARB for the AT1 receptor [12].

The inadequate capabilities of RAAS blockers prompted scientists to explore alternative therapeutic approaches for the treatment of hypertension and to develop drug combinations to improve the effectiveness of the existing drugs. The primary purpose of this research was to develop better and safer antihypertensive treatment that not only controls BP but also reduces the risk of associated fatal complications. The expanding knowledge of RAAS in terms of the identification of new peptides, their action, and receptors has led to the development of several potential therapeutics superior to the available treatments. This review is an attempt to discuss the recent developments in the area of novel targets of the RAAS that might improve the function of organs burdened by hypertension. Our main emphasis is a discussion of the experimental and clinical evidence of the effects of emerging RAAS targets in hypertension and the associated pathological conditions.

Novel therapeutic approaches targeting RAAS in hypertension treatment

Several novel peptide- and nonpeptide- based therapeutic agents are currently at different stages of development, with some already approved by the USFDA for cardiovascular treatment (Supplementary Table 1). The chemical structures of some of these peptides and nonpeptides are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Preclinical (Table 1) and clinical studies (Table 2) have demonstrated a conspicuous impact on hypertension and its associated complications of these novel agents, namely, ACE2/Ang (1–7)/MasR axis activators, dual inhibition with neprilysin, soluble guanylyl cyclase A (sGC) stimulation, dual activating bispecific peptides, antioxidants, nonsteroidal MR antagonists, and aminopeptidase A (APA) inhibitors, which are in different phases of clinical trials. Below, we will discuss the outcome of these ongoing preclinical and clinical trials.

The angiotensin II receptor (AT2R)

Ang II is the central hormone of the RAAS that produces vasoconstriction and vasodilatory effects through AT1 and AT2 receptors, respectively (Fig. 1). The expression of the AT2 receptor is maintained at low levels under healthy conditions; however, under disease conditions such as renal failure, vascular injury and myocardial infarction, its expression is drastically upregulated for endogenous protection [13]. AT2 receptor stimulation demonstrates a significant effect on tissue repair and cell differentiation and promotes diuresis and natriuresis; [14] moreover, it has proven beneficial to the brain, lungs, heart, blood vessels, kidney, pancreas, and skin [15, 16]. Ang II-mediated vasorelaxation is believed to occur through the AT2 receptor and is facilitated by nitric oxide synthase/nitric oxide (NOS/NO) signaling pathways [17]. The natriuresis and defensive actions of the AT2 receptor are mediated through the production of renal vasodilatory peptides such as bradykinin, nitric oxide and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) (Fig. 2) [18]. Currently, four AT2 receptor agonists are under preclinical investigation. Among these, one is a nonpeptide agonist compound 21 (C21), and three are peptidergic agonists: β-Tyr4-Ang II, β-Ile5-Ang II, and LP2-3. Details of ongoing preclinical studies involving C21 are given in Table 2. Treatment with C21 for 7 days resulted in a significant improvement in heart function [19]. The protective effect of C21 on renal damage was shown to occur through a reduction in inflammatory and fibrotic pathways in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) [20]. In 2015, Kemp et al. reported that activation of the systemic AT2 receptor induces natriuretic effects in both acute and chronic conditions in rats and mice, respectively. The selectivity of C21, an AT2 receptor agonist, was confirmed with the administration of the AT2 receptor antagonist PD123319 and by using AT2 receptor knockout mice [14]. These selective nonpeptide AT2 receptor agonist findings could potentially lead to the therapeutic management of salt/water retention disorders and their possible application in the management of hypertension in the near future.

Detailed layout of promising pathways in hypertension. AT2R, MasR, and pGC-A receptor-mediated downstream pathways in the management of hypertension to prevent end-organ damage. Sarcoma Homology 2 Domain Phosphatase-1 (tyrosine phosphatase) (SHP-1), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NADPH oxidase), Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1, MAPK), Protein phosphatase 2 (PP2), extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK1/2), Phospholipase A2 (PLA2), arachidonic acid (AA), Bradykinin receptor (B2R), Protein Kinase A (PKA), Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT), Protein kinase C (PKC), Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β), Nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT), guanosine triphosphate (GTP), transforming growth factor beta (TGFB), Interleukin 6 (IL-6), Caspase-3 (Casp-3), Collagen type I (Col-1), Protein Kinase G (PKG), phosphodiesterase (PDE), Adenosine monophosphate (AMP), Glomerular filtration rate (GFR)

Other peptide Ang II analogs, such as 5 β-Tyr4-Ang II and β-Ile5-Ang II, are responsible for weak, NO-dependent AT2 receptor-mediated vasorelaxation in the mouse aorta [21]. In addition, the β-Ile5-Ang II analog also lowers high BP in combination with candesartan [22]. Currently, an ongoing clinical trial (NCT03806283) is evaluating the role of the AT2 receptor in the modulation of vascular dysfunction using vessels isolated from omental biopsies. This trial could provide evidence of fetal vascular dysfunction mediated by decreased expression of the AT2 receptor in preeclampsia using vessels isolated from the placenta.

Another AT2 receptor agonist, CGP42112, exerts anti-inflammatory action by reducing the activation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB), and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) activation [23]. In addition, there is evidence that physical interactions of the AT2 receptor and Mas receptor (MasR) are involved in regulating BP and antihypertensive activity [24]. AT2 receptor agonists are expanding their role in hypertension and associated diseases.

The ACE2/Ang(1–7)/MasR protective axis

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is a member of the carboxypeptidase family and is similar to ACE. ACE2 has a high affinity toward the peptide Ang II and cleaves it to angiotensin 1–7 (Ang 1–7). Similarly, ACE2 also converts Ang I into angiotensin 1–9 (Ang 1–9); subsequently, Ang (1–9) is converted to Ang (1–7) by the enzyme ACE. The peptide Ang (1–7) acts through the proto-oncogene MasR, a G protein-coupled receptor. The ACE2/Ang(1–7)/MasR axis demonstrates protective action, as it minimizes the harmful actions of the classic ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis (Fig. 2) [25]. The details of various ongoing preclinical and clinical trials involving these peptides are given in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Previously, it was reported that in animals with healthy kidneys, the expression of ACE2 was significantly increased. In contrast, the expression of ACE remains low, whereas under severe pathological conditions of the heart and kidney, the expression of ACE2 is significantly reduced and that of AT1 and ACE is significantly increased [26]. Existing evidence supports diverse roles for ACE2 in severe pathological conditions, notably in the regulation of cardiac and renal function. Significant progression of fibrosis and inflammatory mediators has been observed in the Ang II-induced model of ACE2 knockout mice [27]. In addition, ACE2 disruption in mice contributes to increased Ang II expression, contractility defects and increased levels of hypoxia-induced genes [28]. These data highlight the essential role of ACE2 in the regulation of cardiac and renal function.

The ACE2 activator diminazene aceturate (DIZE) suppresses hemodynamic and morphological alterations in a myocardial infarction rat model [29]. It also has a protective effect on cardiac and histopathological manifestations in rats and is beneficial in arrhythmias, such as electrophysiological dysfunction [30]. Conversely, an ongoing clinical trial (NCT00886353) is testing the recombinant form of ACE2 for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. In a diabetic mouse model, recombinant human ACE2 (rhACE2) showed promising results in reducing the progression of diabetic nephropathy [31]. It also lowered high BP and reduced the progression of cardiac fibrosis in hypertensive animal models [28]. The beneficial role of ACE2 in chronic kidney disease was demonstrated in a preclinical model of Ang II induced hypertension and diabetes mellitus [32]. Since bulk production of rhACE2 is quite expensive, research is now focused on bacteria-derived carboxypeptidases that require B38-CAP and are easily prepared in E. coli. B38-CAP activity contributes to the cleavage of Ang I and Ang II to Ang (1–7) and downregulates Ang III levels in mice [33]. B38-CAP treatment can also suppress the progression of Ang II-induced hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. Furthermore, bacteria derived from human ACE2-like enzymes might indicate a new direction for a cost-effective treatment strategy.

Peptide Ang (1–7), which acts through MasR, significantly suppresses inflammation, hypertrophy, and fibrosis and elevates BP by dilating blood vessels in hypertensive animal models [34]. Ang (1–7) also shows promising effects in cardiovascular diseases, including antihypertensive and antiarrhythmic effects and inhibition of cardiac remodeling [35]. The nonpeptide agonist of MasR, AVE-0991, mimics the action of endogenous peptide Ang (1–7) by vasodilation and natriuresis in many tissues. AVE-0991 is more stable than Ang (1–7) and has a longer biological half-life [36]. Treatment with AVE-0991 is effective in cardiorenal diseases, possibly via improvement of the metabolism of glucose and lipids [37]. Genetic deletion of MasR contributes to increased glomerular filtration, renal fibrosis and proteinuria in C57Bl/6 mice [38]. Clinical and experimental evidence suggests that increasing/activating ACE2/Ang (1–7) results in the prevention of heart diseases such as heart failure (Tables 1 and 2). Ang (1–7) increases NO production in the ascending loop of Henle via activation of MasR, which in turn minimizes the harmful effects of Ang II in renal segments, such as the thick ascending loop of Henle [39]. This ACE2/Ang (1–7)/MasR protective axis showed promising beneficial outcomes in hypertension and peripheral artery disease clinical trials; therefore, it represents a prominent therapeutic alternative strategy in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. In addition to hypertension and cardiovascular diseases, the ACE2/Ang (1–7)/MasR axis also shows noticeable effects in noncardiac diseases such as cancer and chronic pain syndromes, as well as in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 [40, 41]. The recently reported increased expression of the ACE2 receptor in animals administered ACE inhibitors and ARBs has led to a debate on the safe use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in patients with COVID-19 [42]. Although the evidence gathered so far from observational studies has weighed against any positive correlation between the use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs and increased risk for COVID-19, more conclusive evidence is required to rule out any such correlation [42].

Natriuretic peptide and neprilysin

The function of the heart is not only to pump blood but also to act as an endocrine system that produces hormones participating in the regulation of BP, cardiac structure and water balance [43]. The best example is natriuretic peptides (NPs), an assembly of hormones with diverse effects. The different NPs secreted by the human heart are atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP). These NPs act through specific receptors known as natriuretic peptide receptors (NPRs) and are classified as NPR-A, NPR-B, and NPR-C [44]. These NPs interact with membrane-bound particulate guanylyl cyclase (pGC), which consists of a ligand-binding cytoplasmic guanylyl cyclase domain. The NPR-A and NPR-B receptors are also known as guanylyl cyclases A and B (GC-A and GC-B). ANP and BNP exert their physiological effects through GC-A/NPR-A and initiate intracellular signaling. Activated GC-A intensifies the intracellular concentrations of a secondary messenger, cGMP (Fig. 2). It contributes to the activation of protein kinase G (PK-G), leading to vasodilation and natriuretic and diuretic effects [45]. The potent effect of NPs through GC-A receptor signaling presents a potential therapeutic alternative in hypertension treatment by inhibiting P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and ameliorating glomerular injury by protecting against podocyte injury [46]. The infusion of carperitide, a synthetic human ANP; vastiras, a recombinant pro ANP; and nesiritide, a human recombinant BNP have yielded promising results for the treatment of heart diseases. Vastiras exhibited promising physiological effects, such as vasodilation, natriuresis and diuresis [47]. Nesiritide showed beneficial effects in patients with hypertension (Table 2). Moreover, in patients with chronic kidney disease, perioperative low-dose carperitide (hANP) infusion has shown renal protective effects in nondialysis patients [48]. NPs have proven useful as a therapeutic alternative, but they are degraded quickly by tissue proteases, hence the need for continuous intravenous infusion during treatment. This problem is overcome via modification of native NPs [49].

Guanylate cyclase exists in cells in a membrane-spanning form (pGC) and soluble form (sGC). Innovative research in peptide engineering contributed to enhanced pGC-A stimulator activity and improved the short half-lives of endogenous peptides. A novel pGC-A activator/designed natriuretic peptide CRRL269 demonstrated vasorelaxation and antihypertensive effects on the renal and cardiac system model of ischemia-induced acute kidney injury in canines [50]. The latest designer NP that recently entered a clinical trial for hypertension treatment is MANP (ZD100), which also acts as a prominent pGC-A activator. ZD100 was demonstrated to be safe and highly efficacious in reducing BP with a single subcutaneous administration in a human study with significant renal protective function and reduced aldosterone levels [51]. Another pGC-A activator, ANX-042, was proven to be safe in healthy volunteers, and it was shown to activate the secondary messenger cGMP [52].

Neprilysin (NEP) is a membrane-bound zinc endopeptidase present in various organs. NEP contributes to the breakdown of vasoactive peptides such as bradykinin and NPs. Therefore, a neprilysin inhibitor (NEPi) prevents the degradation of vasoactive peptides, including bradykinin, calcitonin gene-related peptide, adrenomedullin, and endothelin-1 [53]. The favorable effects of NEPi are vasodilation, enhanced diuretic action, natriuresis, reduced sympathetic activity and long-term stimulation of anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic and antihypertrophic effects on cardiomyocytes invitro [54]. However, treatment with NEPi alone fails to challenge the available therapies owing to the absence of safety and efficacy data. These events provoked investigations on the beneficial, potent and safe combinations of the NEPi-ARB and NEPi-ACE classes. Inhibition of NEP, along with RAAS blockers, also improves the bioavailability of protective NPs and supports treatment against cardiorenal diseases [55]. Recently, studies were successful in demonstrating the significant effects of this combination therapy, and it might represent a novel treatment for preventing the development of cardiac and renal complications. A combination of ACEi-NEPi, named vasopeptidase inhibitors (VPi), has been developed and examined for cardiovascular diseases. Omapatrilat is the most studied VPi, but it has failed in clinical trials due to the side effects of angioedema [56]. Ilepatril (AVE 7688) VPi has entered a phase 3 clinical trial. Chronic dual NEP-endothelial converting enzyme (ECE) inhibition contributed to significant improvement in endothelial function and exerted protective effects against renovascular hypertension [57]. LCZ696 is the prototype of the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNi) class, a combination of the ARB moiety valsartan and the NEPi prodrug sacubitril. LCZ696 was proven to be devoid of any severe side effects of angioedema, as it halts the metabolism of bradykinin. LCZ696 was found to be superior to the ARB enalapril in cardioprotection. The ARNi LCZ696 improved outcomes in cardiac dysfunction and suppressed cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis and vasculopathy [58]. In another randomized double-blind clinical trial, LCZ696 was shown to be safe and effective for the treatment of cardiovascular disorders [59]. In 2015, LCZ696 was approved by the USFDA for the treatment of cardiovascular disorders (Supplementarty Table 1).

Stimulation of soluble guanylyl cyclase A

Similar to the NP/pGC/cGMP signaling cascade, the NO/sGC/cGMP pathway plays a prominent role in the maintenance of the physiological functions of major organs. sGC stimulators initiate cardiorenal protection with the help of cardiac hormones and their endogenous ligands by directly binding to sGC and activating cGMP production [60]. The details of various ongoing clinical trials are given in Table 2. The NO/sGC/cGMP signaling transduction pathway regulates various pathological conditions of the cardiac and renal systems [61]. There are two main reasons: one is the gaseous signaling molecule NO, which is mainly responsible for critical processes such as vasorelaxation, cell proliferation, neurotransmission, immunity, platelet aggregation and mitochondrial respiration. The downregulation of NO signaling leads to cardiovascular diseases, renal injury, sepsis, pulmonary injury and major organ failure [62]. The second and most important reason is oxidative stress, which interferes with the NO/sGC/cGMP pathway. It is also a plausible threat to many severe pathological conditions.

A strategy for increasing the secondary messenger cGMP is via NO donors, the use of sGC stimulators and sGC activators or the prevention of cGMP degradation by blocking the cGMP-degradation enzymes phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) and 9 (PDE9) [63]. The first compound introduced was riociguat, a sGC stimulator used in the treatment of different forms of pulmonary hypertensive conditions. It improves clinical outcomes in pulmonary hypertension following complete surgical repair of chronic heart disease [64]. Several preclinical reports suggest that sGC stimulators could become a widely used treatment choice for cardiovascular and renal disorders (Table 1). In cholestatic cirrhosis conditions, riociguat ameliorated portal hypertension, reduced liver fibrosis, and inhibited hepatic inflammation [65]. In experimental chronic heart failure conditions, heme-free BAY 58-2667, a sGC activator, has effective systemic and renal vasorelaxant actions. It also significantly improves cardiac output, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), natriuresis and diuresis in chronic heart failure conditions [66]. Promising sGC stimulators such as riociguat (BAY 41-2272), vericiguat (BAY 60-4552), 2-[1-[(2-fluorophenyl)methyl]-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridin-3-yl]-5(4-morpholinyl)-4,6-pyrimidinediamine (BAY 41–8543) and sGC activators such as BI 703704, cinaciguat, GSK2181236A, and ataciguat have also shown prominent protective action in severe pathological conditions. In addition, sGC stimulators have promising antifibrotic, antihypertrophic and anti-inflammatory effects [66]. In summary, the unique mechanism of action of sGC stimulators might be beneficial, leading to enhanced renal and cardiac function in hypertension and combatting the progression of associated diseases.

Dual-acting bispecific peptides

Expansion in peptide engineering with a multivalent strategy as a new promising therapeutic approach is needed to prevent the burden of vital organ diseases. After the successful experimental demonstration of the dual inhibitory properties of LCZ696 in 2010, scientists developed a class of novel bispecific peptides. The details of various dual-acting bispecific peptides that are currently being investigated in preclinical models are shown in Table 1. The primary function of bispecific peptides is to mimic the action of an endogenous peptide, which acts on two separate signaling pathways that contribute to amplifying the final effects of individual pathway activation. Cenderitide was the first dual-acting peptide that activates the NP receptors pGC-A and pGC-B. The biological action of NPs mediated through pGC-A and pGC-B results in natriuresis, vasodilation, renin and aldosterone inhibitionand antiapoptotic, antihypertrophic, and antifibrotic effects [67]. Cenderitide successfully showed natriuretic properties and cardiorenal protective effects [68], as well as antifibrotic properties, in a rat model of early cardiac fibrosis [69]. NPA7, a combination of an amino acid sequence of BNP (an endogenous ligand for a pGC-A receptor) and an Ang (1–7) amino acid sequence (an endogenous activator of MasR),is another novel dual-acting peptide that activates pGC-A and MasR. As discussed above, stimulation with pGC-A activates the secondary messenger cGMP pathway, which leads to natriuresis, diuresis, and antihypertensive and antihypertrophic effects. On the other hand, independent MasR activation contributes to antiapoptotic, anti-inflammatory, vasodilatory, and antithrombotic effects through its secondary messenger cAMP (Tables 1 and 2). Subcutaneous administration of NPA7 mediated cardiac unloading and diuretic, natriuretic and RAAS-suppressing actions in healthy canines [70]. NPA7 proved superior in hemodynamic effects, natriuresis, diuresis and cardiorenoprotective effects in heart failure models [71]. The synergetic action of the bispecific peptide NPA7 and furosemide proved beneficial in experimental heart failure [72]. NPA7 also showed BP-lowering effects in a dose-dependent manner and protected organs from damage in SHRs [72]. However, studies need to be conducted to explore dual-acting bispecific peptides as a therapeutic option in hypertension management and prevention of target organ damage.

Antioxidant therapy

Oxidative stress plays a vital role in the progression of renal, vascular and cardiac diseases, whereas the administration of antioxidants demonstrates protective effects [73]. One of the primary pathways in Ang II-induced hypertension pathophysiology involves NADPH oxidase-derived ROS. The linkage between the RAAS and progression of hypertension is through the AT1 receptor; it leads to renal and systemic vasoconstriction, which increases sodium reabsorption directly and indirectly through the action of aldosterone at the distal nephron [74]. These actions lead to the development of hypertension under pathophysiologic conditions.

Antioxidant therapy can be a useful treatment strategy for maintaining the impaired balance between oxidants and antioxidants in disease conditions. Studies have shown the management of hypertension with vitamins, antioxidants, superoxide dismutase mimetics, ROS scavengers, and apocynin-like NADPH oxidase inhibitors [75]. Among the antioxidants, vitamin D is emerging as a new antihypertensive treatment with antioxidant properties. Vitamin D treatment in pulmonary hypertensive rats enhanced the survival rate by decreasing right ventricular hypertrophy [76]. Tempol, a superoxide dismutase-mimetic drug, significantly reduced BP in SHRs and showed protective effects in a chronic renal injury model [77].

Conversely, some emerging antihypertensive drugs have antioxidant activity, which is currently attracting the attention of researchers. Among them are celiprolol, propranolol, nebivolol, and carvedilol. In a recent study, the intake of nebivolol prevented oxidative stress-mediated target organ damage [78]. Nebivolol also has a protective effect in combating hypertension and vascular oxidative stress, as shown in chronically ethanol-treated rats [79]. The clinical and preclinical data suggest the potential use of antioxidants as antihypertensive treatments (Tables 1 and 2). From a future perspective, RAAS-mediated oxidative stress can be a significant target in the management of hypertension.

Nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist

The mineralocorticoid steroid hormone aldosterone mainly acts through MR. Aldosterone performs its principal function by regulating the sodium and potassium balance, which contributes to BP control. Hence, an imbalance in aldosterone levels can lead to the progression of heart and kidney diseases by increasing oxidative stress, inflammatory mediators and fibrotic factors. Extensive clinical trials support the efficacy and safety of steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), such as spironolactone and eplerenone, by reducing BP in subjects with resistant hypertension. The application of these classes of drugs is limited due to the high frequency of adverse effects such as hyperkalemia [80]. Hence, there is a need to develop novel nonsteroidal dihydropyridine to overcome the side effects of steroidal antagonists.

Conventionally, dihydropyridines are used as L-type calcium channel antagonists. Examples of this new class of antagonists are finerenone, which is currently in the advanced phase of clinical trials for cardiovascular and liver complications. Finerenone reduces albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and diabetic nephropathy without causing adverse effects such as hyperkalemia or renal dysfunction [81]. In randomized clinical trials, finerenone showed significant improvement in subjects with worsening chronic cardiac and renal disease conditions compared to eplerenone (Table 2). Finerenone also proved to be more beneficial in reducing cardiac hypertrophy and proteinuria than eplerenone [82]. The development of finerenone is an essential treatment and critical step in the use of nonsteroidal MRAs for hypertension [83].

Two other nonsteroidal MRA compounds, esaxerenone and apararenone, are also currently undergoing clinical trials (Table 2). Esaxerenone demonstrated cardiac and renal protective activity in deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) salt-induced hypertensive rats compared to spironolactone or eplerenone. In another trial, esaxerenone also exhibited significant antihypertensive and renal protective effects through inhibition of renal inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways [84]. In a phase II randomized clinical trial, esaxerenone showed superior efficacy and safety profiles to steroidal MRA in essential hypertensive conditions without any risk of unwanted side effects such as hyperkalemia [85]. Furthermore, the recently published outcomes of a long-term phase III clinical trial demonstrated that esaxerenone can effectively achieve the desired BP levels as monotherapy or in combination with antihypertensive drugs. [86]. Recently, two more nonsteroidal MRAs, AZD9977, and KBP-5074, have entered clinical trials (Table 2). AZD9977 is a novel drug with cardiorenal protection without affecting urinary electrolyte excretion, thus avoiding the risk of hyperkalaemia [87]. On the other hand, KBP-5074 demonstrated a reduction in BP, decreased albuminuria and improved cardiorenal outcomes without any severe side effects in rodent models of hypertension and nephropathy [88]. New therapeutic alternatives, such as KBP-5074 and AZD9977, may provide a safe treatment for hypertension control in subjects suffering from hypertension-associated complications without the use of a potassium-lowering agent. Undoubtedly, investigations in this area may significantly contribute to the future development of safe and effective novel MR antagonists.

Aminopeptidase inhibitors

APA metabolizes Ang II to angiotensin III (Ang III), which is further converted to angiotensin IV (Ang IV) by the enzyme aminopeptidase N (APN) (Fig. 1). Both Ang II and Ang III show an equal affinity for AT1 and AT2 receptors. As discussed above, the Ang II peptide acts through AT1 receptors and causes multiple effects, such as increased BP, increased water intake, salt appetite and pituitary arginine vasopressin (AVP) release in the brain. Ang III is an essential peptide of the brain RAAS and plays an essential role in vasopressin release and BP control [89]. Therefore, specific and selective inhibitors of Ang III might lead to a decrease in BP in hypertensive conditions. Centrally acting APA inhibitors are a class of drugs that inhibit the generation of Ang III, and they represent an efficient therapy for the treatment of hypertension-related diseases [90].

APA inhibition normalizes brain RAAS, promotes cardiac function, and inhibits hypertrophy and fibrosis in a myocardial infarction mouse model [91]. These findings resulted in the development of potent and safe centrally acting antihypertensive agents such as the APA inhibitor firibastat (code names RB150 and QGC001). The selective APA inhibitor EC33 does not cross the blood-brain barrier; therefore, researchers have developed systemically active prodrugs. When orally administered firibastat prodrug crosses the gastrointestinal and blood-brain barriers and enters the brain, it produces two molecules of EC33 that inhibit brain APA activity, block brain Ang III formation, and control BP. In addition, it reduced BP in preclinical models of hypertension [92]. Firibastat is useful in the downregulation of plasma AVP, increases diuresis and natriuresis, and thus promotes a decline in blood volume [93]. The findings of Ferdinand et al. support the strategy of using brain APA inhibitors to lower BP in subjects with resistant hypertension [94]. NI956/QGC006 is a new centrally acting APA inhibitor that is more effective than EC33 in lowering BP [95]. Extensive preclinical and clinical trials show the efficacy and safety of APA inhibitors, resulting in a sustained decrease in BP via downregulation of systemic AVP release and sympathetic activity and improvement in the baroreflex function of hypertensive animal models (Tables 1 and 2). Therefore, inhibition of APA initiates a new direction for hypertension treatment.

Previous reports suggest that APN may play a central role in the pathogenesis of salt-sensitive hypertension [96]. Hence, APN inhibitors represent a promising therapeutic alternative in the treatment of hypertension. The APN inhibitor PC-18 significantly inhibited the natriuretic response in AT1 receptor-blocked rats [97]. Renal interstitial infusion of PC-18 also ameliorated defective AT2 receptor-mediated natriuresis and hypertension in young SHRs [98]. As we mentioned earlier, experiments were performed successfully using a combination of NEP/ACE and NEP/ARB together to treat hypertension. In recent years, the effect of the combined use of ACE, NEP and APN inhibitors in treatment has opened a new direction for hypertension research. This study showed that a combination of ACE, NEP and APN can effectively reduce cardiac hypertrophy, hypertension and fibrosis in dexamethasone-induced hypertension models [99]. However, further research is needed to investigate the effect of this innovative combination with aminopeptidase inhibitors to explore their therapeutic properties in hypertension models.

IRAP inhibitor

Insulin-resistant aminopeptidase (IRAP), the Ang IV receptor, was identified in 2001 [100]. The enzyme IRAP is yet another promising target for hypertension management. Ang IV peptide is responsible for vasorelaxation in pulmonary artery endothelial cells [101]. Conversely, Ang IV acts as a vasoconstrictive agent in the rat basolateral artery through the AT4 receptor [102]. For this reason, Ang IV and its peptide analogs, as well as nonpeptide inhibitors of IRAP, are drawing interest in hypertension research. IRAP is involved in the degradation of vasopressin and oxytocin. It is also known that Ang IV elevates BP and reduces renal blood flow via the AT1 receptor [103].

The IRAP inhibitor HFI-419 provides a new treatment for well-known cardiac diseases, leading to improved target organ function [104]. HFI-419 offers improved antifibrotic efficacy and renoprotection compared to candesartan cilexetil (CAND). HFI-419 also proved safer and showed better antifibrotic efficacy than the ACE inhibitor perindopril (PERIN) in murine high salt-induced kidney damage [105]. Reports also suggest that IRAP deletion in mice attenuates lipid accumulation in the plaque area and inhibits plaque rupture. These results suggest a novel association between angiotensin signaling and atherogenesis [106]. Two IRAP inhibitors, HFI-419 and SJM4-164, proved superior to the ACE inhibitor perindopril in renoprotection and potent antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects [107]. In future studies, IRAP inhibitors might prove useful against cardiac and renal damage. Additional studies are required to prove the effectiveness of IRAP inhibitors as a novel therapeutic alternative for hypertension treatment.

Summary and perspective

The increased burden of hypertension and its associated complications has required the development of a new class of safe and effective therapeutic agents, as the currently available drugs, despite their efficacy in lowering BP, have adverse side effects after prolonged use. In addition, evidence also suggests that RAAS inhibitors, the predominant antihypertension medication currently in use, may inadequately block the RAAS. To address this unmet need, the focus of research in the recent past has shifted more toward investigations of novel peptide and nonpeptide analogs of endogenous peptides of the ACE2/Ang (1–7)/MasR axis, the protective arm of the RAAS rather than the classic arm. The new promising targets that we have discussed in this review are supportive of decreasing the burden of hypertension-associated diseases, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Several novel peptide and nonpeptide drugs have shown better efficacy and safety in clinical trials than existing drugs. In the future, peptide-based strategies may prove a better option due to a lack of adverse side effects and the prevention of end organ damage. Designer peptides of endogenous peptide origin would be a better option to avoid any serious side effects. Alternatively, the combination of classic RAAS inhibitors and drugs that upregulate hormones of the protective arm of the RAAS may also prove to be an effective treatment option, for instance, the simultaneous upregulation of secondary messenger cGMP and downregulation of the RAAS. In addition to peptide- and nonpeptide-based strategies, various other approaches are under investigation to treat hypertension and associated complications. A recent study by Ujil et al. demonstrated that angiotensinogen siRNA mediated cardioprotective effects by reducing hypertension, which is another significant step toward the development of better hypertension treatment [108]. Various AT2 receptor stimulators and IRAP inhibitors have also been developed for protective purposes. Inhibition of the RAAS with APA inhibitors at specific locations, such as the brain, can also effectively control hypertension [44]. All these novel approaches, especially bispecific peptides, are revealing new directions in the hypertension drug development arena. Furthermore, minor modifications in peptides have demonstrated enhanced efficacy and extended biological half-life compared with parental peptides. In the coming years, these new approaches may prove to be more effective and safe for hypertension treatment and associated target organ damage than existing approaches, as more studies are required to fully explore the therapeutic properties of these drugs.

Summary of RAAS overactivation. Overactivated RAAS affects various cellular processes in vital organs, which leads to the burden of hypertension-associated diseases. Commercially available drugs are associated with inadequate action and intolerable adverse effects. Hence, this prompted the investigation of new emerging targets. Antidiuretic hormone (ADH), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA),connective tissue growth factor (CTFG), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), chronic kidney disease (CKD), myocardial infarction (MI), end stage renal disease (ESRD), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-Kβ)

References

Mills KT, Stefanescu A, He J. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control a systematic analysis of population based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016;134:441–50.

Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16:223–37.

Oparil S, Acelajado MC, Bakris GL, Berlowitz DR, Cífková R, Dominiczak AF, et al. Hypertension. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18014.

Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Government of India, Screening, Diagnosis, Assessment, and Management of Primary Hypertension in Adults in India. Standard Treatment Guidelines. 2016;1-143.

Ocaranza MP, Riquelme JA, García L, Jalil JE. Counter regulatory renin–angiotensin system in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:116–29.

Oparil S, Schmieder RE. New approaches in the treatment of hypertension. Cir Res. 2015;116:1074–95.

Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II cell signaling: physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:82–97.

Kumar U, Wettersten N, Garimella PS. Cardiorenal syndrome pathophysiology. Cardiol Clin. 2019;37:251–65.

Nguyen Q, Dominguez J, Nguyen L, Gullapalli N. Hypertension management: an update. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2010;3:47–56.

Steckelings UM, Paulis L, Unger T, Bader M, Muscha U, Paulis L. Expert opinion on emerging drugs emerging drugs which target the renin – angiotensin – aldosterone system Emerging drugs which target the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2011;16:619–30.

Jorde UP, Ennezat PV, Lisker J, Suryadevara V, Infeld J, Cukon S, et al. Maximally recommended doses of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors do not completely prevent ACE-mediated formation of angiotensin II in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2000;101:844–6.

Bomback AS, Toto R. Dual blockade of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system: beyond the ACE inhibitor and angiotensin-II receptor blocker combination. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:1032–40.

Benndorf RA, Krebs C, Hirsch-hoffmann B, Schwedhelm E, Cieslar G, Schmidt-haupt R. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor deficiency aggravates renal injury and reduces survival in chronic kidney disease in mice. Kidney Int. 2009;75:1039–49.

Kemp AB, Nancy LH, John JG, Susanna RK, Shetal HP, Robert MC. AT2 receptor activation induces natriuresis and lowers blood pressure. Cir Res. 2015;115:388–99.

Colafella KMM, Danser AHJ. Recent advances in angiotensin research. Hypertens. 2017;69:994–99.

Bertelsen JB, Peluso AA. Anti‐fibrotic mechanisms of angiotensin AT 2 ‐receptor stimulation. Acta Physiol. 2019;227:e13280.

Savoia C, Ebrahimian T, He Y, Gratton J, Schiffrin EL, Touyz RM. Angiotensin II/AT 2 receptor-induced vasodilation in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats involves nitric oxide and cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J Hypertens. 2006;24:2417–22.

Sosa-Canache B, Cierco M, Ine’s Gutierrez C, Israel A. Role of bradykinins and nitric oxide in the AT 2 receptor-mediated hypotension. J Hum Hypertens. 2000;14:S40–6.

Kaschina E, Grzesiak A, Li J, Foryst-ludwig A, Timm M, Rompe F. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation a novel option of therapeutic interference with the renin-angiotensin system in myocardial infarction? Circulation. 2008;118:2523–32.

Gelosa P, Pignieri A, Fa L, Hallberg A, Banfi C. Stimulation of AT2 receptor exerts beneficial effects in stroke-prone rats: focus on renal damage. J Hypertens. 2009;27:2444–51.

Riet L, van Esch JoepHM, Roks AntonJM, van den Meiracker AntonH, Jan AH Danser. Hypertension renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system alterations. Circ Res.2015;116:960–76.

Jones ES, Borgo MPDel, Kirsch JF, Clayton D, Bosnyak S, Welungoda I. A single amino acid substitution to angiotensin II confers AT 2 receptor selectivity and vascular function. Hypertens. 2011;57:570–76.

Zhu L, Carretero OA, Xu J, Harding P, Ramadurai N, Gu X. Activation of angiotensin II type 2 receptor suppresses TNF-ά -induced ICAM-1 via NF- B: possible role of ACE2. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:827–34.

Patel S, Hussain T. Dimerization of AT 2 and mas receptors in control of blood pressure. Cur Hypertens Rep. 2018;20:41.

Romero CA, Orias M, Weir MR. Novel RAAS agonists and antagonists: clinical applications and controversies. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:242–45.

Danilczyk U, Penninger JM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme II in the heart and the kidney. Cir Res. 2006;98:463–71.

Liu Z, Huang X, Chen H, Fung E, Liu J, Lan H. Deletion of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 promotes hypertensive nephropathy by targeting Smad7 for ubiquitin degradation. Hypertens. 2017;70:822–30.

Crackower MA, Sarao R, Oudit GY, Yagil C, Kozieradzki I, Scanga SE, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature. 2002;417:822–28.

Castardeli C, Sartório CL, Pimentel EB, Forechi L, Mill JG. The ACE 2 activator diminazene aceturate (DIZE) improves left ventricular diastolic dysfunction following myocardial infarction in rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;107:212–18.

Joviano-Santos JV, Santos-Miranda A, Joca HC, Cruz JS, Ferreira AJ. Diminazene aceturate (DIZE) has cellular and in vivo antiarrhythmic effects. Clin Exp Pharm Physiol. 2020;47:213–19.

Oudit GY, Liu GC, Zhong J, Basu R, Chow FL, Zhou J, et al. Human recombinant ACE2 reduces the progression of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2010;59:529–38.

Williams VR, Scholey JW. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and renal disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2017;27:35–41.

Minato T, Nirasawa S, Sato T, Yamaguchi T, Hoshizaki M, Inagaki T. B38-CAP is a bacteria-derived ACE2-like enzyme that suppresses hypertension and cardiac dysfunction. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1058.

Mendoza-torres E, Oyarzún A, Mondaca-ruff D, Azocar A, Castro PF, Jalil JE. ACE2 and vasoactive peptides: novel players in cardiovascular/renal remodeling and hypertension. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;9:217–37.

Jiang F, Yang J, Zhang Y, Dong M, Wang S, Zhang Q. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and angiotensin 1–7: novel therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:413–26.

Wiemer G, Dobrucki LW, Louka FR, Malinski T, Heitsch H. AVE 0991, a Nonpeptide Mimic of the Effects of Angiotensin-(1–7) on the Endothelium. Hypertens. 2002;40:847–52.

Singh K, Sharma K, Singh M. Possible mechanism of the cardio- renal protective effects of AVE-0991, a non-peptide Mas-receptor agonist, in diabetic rats. J Renin-Angio-Aldo S. 2012;13:334–40.

Silveira D, Lima CX, Bader M, Rachid M, Augusto R, Santos S. Renoprotective effects of AVE0991, a nonpeptide mas receptor agonist, in experimental acute renal injury. Int J Hypertens. 2012;2012:808726.

Chandrashekar K, Mazzuferi F, Dibo P, Mara RO. Angiotensin- (1–7) inhibits sodium transport via Mas receptor by increasing nitric oxide production in thick ascending limb. Physiol Rep. 2019;7:e14015.

Xu J, Fan J, Wu F, Huang Q, Guo M, Lv Z. The ACE2/angiotensin- (1–7)/mas receptor axis: pleiotropic roles in cancer. Front Physiol. 2017;8:276.

Roshanravan N, Ghaffari S, Hedayati M. Angiotensin converting enzyme-2 as therapeutic target in COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:637–39.

Jarcho JA, Ingelfinger JR, Hamel MB, D’Agostino RB Sr, Harrington DP. Inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2462–64.

Chiba A, Mochizuki N Chapter 14 - Heart hormones. hormonal signaling in biology and medicine. Elsevier Inc.; 2020;327–40.

Arendse LB, Danser AHJ, Poglitsch M, Touyz RM, Burnett JC, Llorens-cortes C. Novel therapeutic approaches targeting the renin-angiotensin system and associated peptides in hypertension and heart failure. Pharm Rev. 2019;71:539–70.

Malek V, Gaikwad AB. Neprilysin inhibitors: a new hope to halt the diabetic cardiovascular and renal complications? Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;90:752–59.

Kato Y, Mori K, Kasahara M, Osaki K, Ishii A, Mori KP. Natriuretic peptide receptor guanylyl cyclase-A pathway counteracts glomerular injury evoked by aldosterone through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46624.

Altara R, Silva GJJ, Frisk M, Spelta F, Zouein FA, Louch WE. Cardioprotective effects of the novel compound vastiras in a preclinical model of end-organ damage. Hypertens. 2020;75:1195–204.

Sezai A, Hata M, Niino T, Yoshitake I, Unosawa S, Wakui S. Results of low-dose human atrial natriuretic peptide infusion in nondialysis patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:897–903.

Goetze JP, Bruneau BG, Ramos HR, Ogawa T, de Bold MK, de Bold AJ. Cardiac natriuretic peptides. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:698–717.

Chen Y, Harty GJ, Zheng Y, Iyer SR, Sugihara S. Sangaralingham SJ.CRRL269 a novel particulate guanylyl cyclase a receptor peptide activator for acute kidney injury. Circ Res. 2019;124:1462–72.

Chen HH, Neutel JM, Smith DH, Heublein D, Medicine JCB. Abstract 15143: ZD100: BP lowering, renal enhancing and aldosterone suppressing properties via pgc-a in human resistant “ like” hypertension - a first in human study. Hypertens. 2020;134:A15143.

Chen HH, Simari RD, Youngberg SP, Grogan DR, Miller JW. Abstract 14201: ANX-042, a novel natriuretic peptide (NP), is safe and stimulates cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) in healthy volunteers. Circulation. 2020;128:A14201.

Mills J, Vardeny O. The role of neprilysin inhibitors in cardiovascular disease. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2015;12:389–94.

Braunwald E. The path to an angiotensin receptor antagonist-neprilysin inhibitor in the treatment of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1029–41.

Judge P, Haynes R, Landray MJ, Baigent C. Full review neprilysin inhibition in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2014;30:738–43.

Zanchi A, Maillard M, Burnier M. Recent clinical trials with omapatrilat: new developments. Cur Hypertens Rep. 2003;5:346–52.

Kalk P, Sharkovska Y, Kashina E, Websky K Von, Relle K, Pfab T. et al. Endothelin-converting enzyme/neutral endopeptidase inhibitor SLV338 prevents hypertensive cardiac remodeling in a blood pressure-independent manner. Hypertension. 2011;57:755–63.

Suematsu Y, Wanghui J, Ane N, Kashyap ML, Khazaeli M, Nosratola DV. et al. LCZ696 (Sacubitril/valsartan), an angiotensin-receptor neprilysin inhibitor, attenuates cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis and vasculopathy in a rat model of chronic kidney disease. J Card Fail. 2018;24:266–75.

Ruilope L, Dukat A, Böhm M, Lacourcière Y, Gong J, owitz M. Blood-pressure reduction with LCZ696, a novel dual-acting inhibitor of the angiotensin II receptor and neprilysin: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, active comparator study. Lancet. 2010;375:1255–66.

Krishnan SM, Kraehling JR, Eitner F, Sandner P, Ignarro L. The impact of the nitric oxide (NO)/soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) signaling cascade on kidney health and disease: a preclinical perspective. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1712.

Kang Y, Liu R, Wu J, Chen L. Structural insights into the mechanism of human soluble guanylate cyclase. Nature. 2019;574:206–10.

Sandner P, Peter J. Anti- fi brotic effects of soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators and activators: A review of the preclinical evidence. Respir Med. 2017;122(Suppl 1):S1–9.

Rosenkranz S, Ghofrani H, Beghetti M, Ivy D, Frey R, Fritsch A, et al. Riociguat for pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease. Heart. 2015;101:1792–9.

Schwabl P, Brusilovskaya K, Supper P, Bauer D, Riedl F, Hayden H. The soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator riociguat reduces fibrogenesis and portal pressure in cirrhotic rats. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9372.

Boerrigter G, Costello-boerrigter LC, Cataliotti A, Lapp H, Stasch J, Burnett JC. Targeting heme-oxidized soluble guanylate cyclase in experimental heart failure. Circulation. 2007;49:1128–33.

Stasch J, Schlossmann J, Hocher B. Renal effects of soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators and activators: a review of the preclinical evidence. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;21:95–104.

Ichiki T, Dzhoyashvili N, Burnett JC. Natriuretic peptide based therapeutics for heart failure: cenderitide: A novel first-in-class designer natriuretic peptide. Int J Cardiol. 2019;15:166–71.

Martin FL, Sangaralingham SJ, Huntley BK, Mckie PM, Ichiki T, Chen HH. CD-NP: a novel engineered dual guanylyl cyclase activator with anti-fibrotic actions in the heart. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52422.

Sugihara S, Ichiki T, Chen Y, Harty GJ, Heublen DM, Iyer SR. Subcutaneous delivery of NPA7, first-in-class novel bispecific designer peptide: enhances cardiorenal function and suppresses renin and aldosterone in vivo and in vitro. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:6342.

Meems L, Andersen I, Huntley B, Harty G, Chen Y, Heublein D. NPA7, a first in class dual receptor activator with cardio-renoprotective properties in-vivo. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:2554.

Meems L, Chen Y, Harty G, Harders J, Iyer S. Abstract 16504: synergist actions of the bispecific peptide, NPA7, and furosemide in experimental heart failure. Circulation. 2020;136:A16504.

Dzhoyashvili NA, Iyer SR, Burnettcardiovascular JC, Clinic M. Abstract 12099: acute antihypertensive action of npa7, innovative bispecific designer peptide, in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circulation. 2019;140:A12099.

Sun H. Current opinion for hypertension in renal fibrosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1165:37–47.

Fanelli C, Zatz R. Linking oxidative stress, the renin-angiotensin system, and hypertension camilla. Hypertens. 2011;57:373–74.

Botelho-ono MS, Pina HV, Sousa KHF, Nunes FC, Medeiros IA, Braga VA. Acute superoxide scavenging restores depressed baroreflex sensitivity in renovascular hypertensive rats. Auton Neurosci Basic Clin. 2011;159:38–44.

Tanaka H, Kataoka M, Isobe S, Yamamoto T, Shirakawa K, Endo J. Therapeutic impact of dietary vitamin D supplementation for preventing right ventricular remodeling and improving survival in pulmonary hypertension. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0180615.

Hamza SM, Dyck JRB. Systemic and renal oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of hypertension: Modulation of long-term control of arterial blood pressure by resveratrol. Front Physiol. 2014;5:292.

Coats A, Jain S. Protective effects of nebivolol from oxidative stress to prevent hypertension-related target organ damage. J Hum Hypertens. 2017;31:376–81.

Vale GT, Simplicio JA, Gonzaga NA, Yokota R, Ribeiro AA, Casarini DE. Nebivolol prevents vascular oxidative stress and hypertension in rats chronically treated with ethanol. Atherosclerosis. 2018;274:67–76.

Nishiyama A. Pathophysiological mechanisms of mineralocorticoid receptor- dependent cardiovascular and chronic kidney disease. Hypertens Res. 2018;42:293–300.

Pérez-gordillo FL, Jesús M, Vega P De, Gerona-navarro G, Rodríguez Y, Alvarez D Advances in the Development of receptor Antagonists.Aldosterone-Mineralocorticoid Receptor - Cell Biology to Translational Medicine. Intechopen.

Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G, Anker SD, Bo M, Køber L, Krum H. A randomized controlled study of finerenone vs. eplerenone in patients with worsening chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus and/or chronic kidney disease. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2105–14.

Katayama S, Yamada D, Nakayama M, Yamada T, Myoishi M, Kato M. A randomized controlled study of finerenone versus placebo in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Complications. 2016;31:758–65.

Duggan S. Esaxerenone: first global approval. drugs. Springe Drugs. 2019;79:477–81.

Rakugi H, Ito S, Itoh H, Okuda Y, Yamakawa S. Long-term phase 3 study of esaxerenone as mono or combination therapy with other antihypertensive drugs in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1932–41.

Ito S, Itoh H, Rakugi H. Effi cacy and safety of esaxerenone (CS-3150) for the treatment of essential hypertension: a phase 2 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. J Hum Hypertens. 2019;33:542–51.

Bamberg K, Johansson U, Edman K, William-olsson L, Myhre S, Gunnarsson A. Preclinical pharmacology of AZD9977: a novel mineralocorticoid receptor modulator separating organ protection from effects on electrolyte excretion. PL0S One. 2018;13:e0193380.

Paul Chow C, Liu JR, Tan XJ, Huang ZH. Pharmacological profile of KBP-5074, a novel non- steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist for the treatment of cardiorenal diseases. J Drug Res Dev. 2017;3:A118.

Reaux A, Fournie-zaluski MC, Llorens-cortes C, Llorens-cortes C, Fournie MC. Angiotensin III: a central regulator of vasopressin release and blood pressure. Trends Endocrin Met. 2001;12:157–62.

Leenen FHH, Ahmad M, Marc Y, Llorens-cortes C. Specific inhibition of brain angiotensin III formation as a new strategy for prevention of heart failure after myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2019;73:82–91.

Emmanuelle S, Marc Y, Keck M, Mougenot N. Brain renin-angiotensin system blockade with orally active aminopeptidase A inhibitor prevents cardiac dysfunction after myocardial infarction in mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2019;127:215–22.

Keck M, Hmazzou R, Llorens-cortes C. Orally active aminopeptidase a inhibitor prodrugs: current state and future directions. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2019;21:50.

Bodineau L, Frugie A, Marc Y, Inguimbert N, Balavoine F, Roques B. Orally active aminopeptidase A inhibitors reduce blood pressure a new strategy for treating hypertension. Hypertens. 2008;51:1318–25.

Ferdinand KC, Black HR. Efficacy and safety of firibastat, a first-in-class brain aminopeptidase a inhibitor, in hypertensive overweight patients of multiple ethnic origins. Circulation. 2019;140:138–46.

Keck M, Almeida HDE, Compere D, Inguimbert N, Flahault A, Balavoine F. NI956/QGC006, a potent orally active, brain-penetrating aminopeptidase A inhibitor prodrug for treating hypertension. Hypertens. 2019;73:1300–07.

Farjah M, Washington TL, Roxas BP, Geenen DL, Danziger RS. Dietary NaCl regulates renal aminopeptidase N: relevance to hypertension in the dahl rat. Hypertens. 2004;43:282–85.

Padia SH, Kemp BA, Howell NL, Siragy HM, Roques BP, Carey RM, et al. Inhibition augments natriuretic responses to angiotensin III in angiotensin type 1. Receptor – Blocked Rats Hypertens. 2007;49:625–30.

Padia SH, Howell NL, Kemp BA, Roques BP, Carey RM, Intrarenal, et al. inhibition restores defective angiotensin II type 2 – mediated natriuresis in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertens. 2010;55:474–80.

Savitha MN, Suvilesh KN, Siddesha JM, Gowda MDM, Choudhury M, Velmurugan D, et al. Combinatorial inhibition of Angiotensin converting enyme, Neutral endopeptidase and Aminopeptidase N by N-methylated peptides alleviates blood pressure and fibrosis in rat model of dexamethasone-induced hypertension. Peptides. 2020;123:170180.

Albiston AL, Mcdowall SG, Matsacos D, Sim P, Clune E, Mustafa T. Evidence that the angiotensin IV (AT4) receptor is the enzyme insulin-regulated aminopeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48623–26.

Patel JM, Edward R, Physiol AJ, Cell L, Physiol M, Angiotensin LL. IV-mediated pulmonary artery vasorelaxation is due to endothelial intracellular calcium release. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L849–56.

Faure S, Javellaud J, Nicole JA. Vasoconstrictive effect of angiotensin IV in isolated rat basilar artery independent of AT 1 and AT 2 receptors. J Vasc Res. 2006;43:19–26.

Yang R, Walther T, Gembardt F, Smolders I, Vanderheyden P, Albiston AL. Renal vasoconstrictor and pressor responses to angiotensin IV in mice are AT1a-receptor mediated. J Hypertens. 2010;28:487–94.

Tracey G, Pong WY, Lee HW, Welungoda I, Chai SY, Widdop RE. 444 AT4 receptor/insulin regulated aminopeptidase deficiency is both vaso- and cardio-protective under condition of cardiovascular stress in mice. J Hypertens. 2012;30:e131–2.

Tracey G, Matthew S, Yan W, Adithya S, Siew YC, Chrishan S, et al. A9684 Comparing anti-fibrotic effects of the irap inhibitor, hfi-419 to an angiotensin receptor blocker and ace inhibitor in a high salt- induced mouse model of kidney disease. J Hypertens. 2018;36:e56–7.

Numaguchi Y, Ishii M, Niwa M, Kuwahata T, Chen XW, Kuzuya M. Abstract 423: ablation of insulin-regulated aminopeptidase (IRAP/AT4R) attenuates lipid accumulation and inhibits plaque rupture in the carotid artery of ApoE deficient mice. Circulation. 2018;118:302.

Chelvaretnam S, Shen M, Mountford SJ, Thompson PE, Chai SY. Abstract 131: insulin regulated aminopeptidase inhibitors are more effective than the ace inhibitor, perindopril in preventing unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced renal fibrosis in mice. Hypertens. 2019;74:A131.

Uijl E, Mirabito Colafella KM, Sun Y, Ren L, van Veghel R. Strong and sustained antihypertensive effect of small interfering RNA targeting liver angiotensinogen. Hypertens. 2019;73:1249–57.

Bourke JE, Rathinasabapathy A, Horowitz A, Horton K, Kumar A. The selective angiotensin II type 2 receptor agonist, compound 21, attenuates the progression of lung fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension in an experimental model of bleomycin-induced lung injury. Front Physiol. 2018;9:180.

Castoldi G, Cira RT, Francesca G, Raffaella R, Giuseppina C, Stella A. Activation of angiotensin type 2 (AT2) receptors prevents myocardial hypertrophy in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Acta Diabetol. 2018;56:97–104.

Dopona EPB, Rocha VF, Furukawa LNS, Oliveira IB, Heimann JC. Myocardial hypertrophy induced by high salt consumption is prevented by angiotensin II AT2 receptor agonist. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2019;29:301–5.

Cao Y, Liu Y, Shang J, Yuan Z, Ping F, Yao S. Ang- (1-7) treatment attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced early pulmonary fibrosis. Lab Invest. 2019;99:1770–83.

Costa JM, Souza EJ, Manoel RSL, Fernanda FB, Santos CA, Pedrino GR. Stimulation of the ACE2/Ang- (1–7)/Mas axis in hypertensive pregnant rats attenuates cardiovascular dysfunction in adult male offspring. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1883–93.

Choi HS, Jin I, Seong C, SK M, Scho JW. Angiotensin-[1–7] attenuates kidney injury in experimental Alport syndrome. Sci Rep. 2020;10:4225.

Chen Y, Zheng Y, Iyer SR, Harders GE, Pan S. C53: A novel particulate guanylyl cyclase B receptor activator that has sustained activity in vivo with anti-fibrotic actions in human cardiac and renal fibroblasts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2019;130:140–50.

Sangaralingham SJ, Huntley BK, Ichiki T, Diseases JCB. Abstract 12893: design and cGMP-generating actions of a novel selective and non-selective particulate guanylyl cyclase B activator targeting cardiorenal fibrotic remodeling. Circulation. 2018;134:A12893.

Sangaralingham SJ, Huntley BK, Ichiki T, Harders GE, Burnettcardiovascular JC. Abstract 12236: a novel particulate guanylyl cyclase B agonist with therapeutic potential targeting fibrosis via cGMP generation for cardiorenal disease. Circulation. 2015;132:A12236.

Boerrigter G, Costello-boerrigter LC, Lapp H, Stasch J, Burnettjr JC. Abstract 2494: beneficial actions of co-targeting particulate and soluble guanylate cyclase dependent cGMP pools in experimental heart failure. Circulation. 2018;116:550.

Shea CM, Price GM, Liu G, Sarno R, Buys ES, Currie MG. Soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator praliciguat attenuates inflammation, fibrosis, and end-organ damage in the Dahl model of cardiorenal failure. Am J Physiol-Ren. 2020;318:148–59.

Hall KC, Bernier SG, Jacobson S, Liu G, Zhang PY, Sarno R. sGC stimulator praliciguat suppresses stellate cell fibrotic transformation and inhibits fibrosis and inflammation in models of NASH.Proc. Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116:11057–62.

Tobin JV, Zimmer DP, Shea C, Germano P, Bernier SG, Liu G. Pharmacological characterization of IW-1973, a novel soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator with extensive tissue distribution, anti-hypertensive, anti-inflammatory, and anti-fibrotic effects in preclinical models of disease. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2018;365:664–75.

Zimmer DP, Shea CM, Tobin JV, Tchernychev B, Germano P, Sykes K. Olinciguat, an oral sGC stimulator, exhibits diverse pharmacology across preclinical models of cardiovascular, metabolic, renal, and in fl ammatory disease. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:419.

Hoffmann LS, Kretschmer A, Lawrenz B, Hocher B. Chronic activation of heme free guanylate cyclase leads to renal protection in dahl salt-sensitive rats. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145048.

Lavall D, Jacobs N, Mahfoud F, Kolkhof P, Böhm M, Laufs U. The non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist finerenone prevents cardiac fibrotic remodeling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2019;168:173–83.

Li L, Guan Y, Kobori H, Morishita A, Kobara H, Masaki T. Effects of the novel nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor blocker, esaxerenone (CS-3150), on blood pressure and urinary angiotensinogen in low-renin Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats. Hypertens Res. 2018;42:769–78.

Arai K, Morikawa Y, Ubukata N, Tsuruoka H, Homma T. CS-3150, a novel nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, shows preventive and therapeutic effects on renal injury in deoxycorticosterone acetate/salt-induced hypertensive rats. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2016;358:548.

Acknowledgements

AB is thankful to UGC (grant no. f.30-352/2017) and ICMR (grant no.RBMH/CAR 1312018-19) for financial support. TG is the recipient of an institutional fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ghatage, T., Goyal, S.G., Dhar, A. et al. Novel therapeutics for the treatment of hypertension and its associated complications: peptide- and nonpeptide-based strategies. Hypertens Res 44, 740–755 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00643-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00643-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Insights into the associative role of hypertension and angiotensin II receptor in lower urinary tract dysfunction

Hypertension Research (2024)

-

Novel aspects of the renin-angiotensin system for pulmonary arterial hypertension

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Comprehensive review on some food-derived bioactive peptides with anti-hypertension therapeutic potential for angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition

Journal of Proteins and Proteomics (2023)

-

Urinary free cortisol excretion is associated with lumbar bone density in patients with adrenal Cushing’s syndrome

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

RSSDI Guidelines for the management of hypertension in patients with diabetes mellitus

International Journal of Diabetes in Developing Countries (2022)