Abstract

The carbon–carbon double bond, with its diverse and multifaceted reactivity, occupies a prominent position in organic synthesis. Although a variety of simple alkenes are readily available, the mild and chemoselective introduction of a unit of unsaturation into a functionalized organic molecule remains an ongoing area of research, and the olefination of carbonyl compounds is a cornerstone of such approaches. Here we show the direct olefination of hydrazones via the intermediacy of three-membered ring species generated by addition of sulfoxonium ylides, departing from the general dogma of alkenes synthesis from carbonyls. Moreover, the mild reaction conditions and operational simplicity of the transformation render the methodology appealing from a practical point of view.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The C–C double bond is a functional group of central importance in organic chemistry, it is expressed as such in countless secondary metabolites and, more importantly, it is arguably one of the most useful functionalities for the practitioners of the art of total synthesis1. Some of the most powerful reactions available to organic chemists rely on the reactivity of olefins: the Heck reaction, olefin metathesis and the Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation are notable examples2,3,4, coincidentally all recognized by Nobel Prizes during the last 16 years. There are a number of different possible approaches for the introduction of a double bond into a molecule, amongst which the olefination of carbonyl moieties is the most developed5, 6. Since the 1950s and the landmark report of the Wittig reaction7, a multitude of variations and new methodologies have been developed, such as the Peterson, Julia, and Tebbe olefinations or the HWE modification of Wittig’s original conditions7,8,9,10,11. Notwithstanding, investigation into the improvement and expansion of the toolset of reactions employed to introduce olefins into molecules remains a rich field of research to this day12,13,14. With this idea in mind, we embarked on the development of a strategy to achieve the olefination of carbonyls.

Typical classifications of olefination methodologies tend to discriminate between the nature of the reagent employed, such as phosphonium ylides (Wittig), sulfones (Julia), silicon-stabilized carbanions (Peterson), or metal alkylidenes (Tebbe). Given that all these reactions are assumed to proceed through cyclic intermediates which undergo different types of cycloreversion reactions in the olefin-yielding step, we propose a different and perhaps richer view, assigning a classification based on the ring size of that key reaction intermediate (Fig. 1a). For instance, the modified Julia (so-called Julia–Kocienski) reaction involves a five-membered spirocyclic intermediate, whereas the Wittig, Tebbe, and Peterson olefinations all proceed via a four-membered ring, as does recently developed aza-phosphetanes chemistry15, 16. The conspicuous scarcity of three-membered ring intermediates in this analysis drove us to develop a new approach to olefination relying on an aziridine intermediate17,18,19,20.

Over the past few years, our group has reported unprecedented transformations that take advantage of underdeveloped reactivity21, 22. In this context, we herein present an unusual and conceptually method for the synthesis of olefins from aldehydes, which we believe brings further diversity to the field while possessing synthetic advantages in its own right.

Results

Initial considerations

Our approach, depicted in Fig. 1b predicated access to an olefin from an aldehyde in a unique process. We proposed the transient generation of an N-iminyl aziridine and its subsequent cheletropic cycloreversion23,24,25,26,27,28 to unveil the desired olefin product.

At the outset of the project, we foresaw two main challenges. First, the formation of an N-iminyl aziridine from a carbonyl precursor in a synthetically useful manner29, 30 and then finding appropriate conditions for a facile cheletropic elimination31.

We eventually settled for the aziridination of an in-situ generated N-iminyl imine (azine) as route to the three-membered ring intermediate (Fig. 1b). Key to addressing the two aforementioned challenges would be the nature of the hydrazone R1 and R2 substituents.

First experiments

In initial experiments, we sought to convert 2-napthaldehyde as model substrate to the corresponding azine. We started our investigation with the use of the hydrazone derived from methyl pyruvate (1a, Table 1). A facile condensation between the two delivered the crude azine (2a) in analytically pure form, on which we explored suitable conditions for aziridine formation. The use of an α-bromo enolate in imino-Darzens-like conditions, as well as the combination of CH2Br2 and butyl lithium were attempted, but without success (Table 1, entries 1 and 2). We next turned our attention to the use of sulfur ylides, generated in situ from sulfonium salts, as nucleophiles32. To our delight, the desired terminal olefin was directly isolated in 9% yield (Table 1, entry 3). Encouraged by this result we turned to sulfoxonium ylides, known to exhibit greater stability, which allowed us to increase the temperature of the reaction33. The use of NaH as base led to the formation of the olefin in 71% yield (Table 1, entry 4). Variation of the base and the counterion helped us to identify t-BuOK as the best combination (Table 1, entries 5–7). Changing the substituents R1 and R2 on the imine moiety did not lead to further improvement (Table 1, entries 8 and 9). Finally, a slight excess of sulfoxonium ylide is necessary to achieve high yield (Table 1, entry 10) and rigorous exclusion of water while beneficial is not mandatory (Table 1, entry 11).

Substrate scope

With suitable conditions for this olefination in hand, we next explored the scope of aromatic aldehydes. As shown in Fig. 2, a diverse array of electron-neutral (3a, 3b), electron-poor (3c–3f), and electron-rich (3g–3i), in addition to heteroaromatic aldehydes (3j–3m), performed well in this protocol. Due to the mildness of the reaction conditions, a wide range of functional groups are well tolerated: esters, nitro groups, amides, ethers, and aryl halides. Importantly, although the overall transformation implies one extra step for N-iminyl imine preparation, this is a very facile operation for all aldehydes studied. Indeed, simple stirring at room temperature in presence of MgSO4 leads to quantitative conversion into the free-flowing, generally yellow powder products. The only side products, detected in the crude products mixtures, are the homologated azines.

We next applied our reaction conditions to α,β-unsaturated azines, derived from enals (Fig. 3a). Surprisingly, the reaction of sulfoxonium ylides with unsaturated azines resulted in a clean 1,2-addition to generate dienes 4 after cheletropic elimination. Notably, no product of conjugate addition was observed by 1H NMR analysis, despite the fact that reaction between sulfoxonium ylides and α,β-unsaturated carbonyls is a textbook transformation. This effectively allows a smooth access to synthetically useful E-configured di- and trisubstituted dienes (4a–4d).

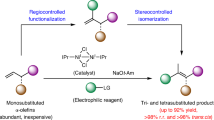

The generality of the reaction was also investigated on aliphatic aldehydes (Fig. 3b). In this case, the use of hydrazone 1b was crucial, as when 1a was employed, a rapid isomerization to an unstable side product (tentatively assigned as the N-iminyl enamine tautomer) was observed. It is likely that 1b, carrying an extended π-system, stabilizes the hydrazone tautomer. Other types of highly conjugated hydrazones with more electron rich system (1d) or more electron poor system (1e), were tested but failed in providing the desired product. Compound 1e exhibited prohibitively slow rate of azine formation and provided trace amounts of olefin with considerable degradation. Compound 1d led to efficient azine formation, but nucleophilic attack from the sulfoxonium ylide was not observed. Finally with the use of hydrazone 1b, the desired olefins could be isolated in good yields after cheletropic extrusion triggered by heating in toluene (5a, 5b). Moreover, the reaction conditions tolerate standard protecting groups such as silyl ether- (5c) and benzyl (5d). To test the limit of applicability of this olefination procedure (Fig. 3c), we applied the reaction conditions to form a trisubstituted olefin starting from either a branched sulfoxonium salt (6a) or from a ketone (6b, 6c), but no aziridine formation could be observed in any of these examples.

Finally, we investigated the applicability of the methodology to the formation of disubstituted olefins (Fig. 4). By employing appropriately substituted and readily accessible sulfoxonium salts, we were able to obtain internal olefins in good to high yields, starting from aromatic aldehydes (7a, 7b, 7c) or aliphatic and conjugated aldehydes (7d, 7e). Notably, the alkene products were obtained with marked E selectivity. This might be a consequence of either stereospecific cheletropic elimination from the more stable trans-aziridine intermediate or non-concerted ring-opening pathways that allow isomerization to take place23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. This E-selectivity is a noteworthy trait of the method.

Significantly, this olefination can also be applied to sensitive aldehyde substrates bearing a stereogenic center at the α-position (Fig. 5). It should be noted that, in contrast to Wittig procedures, which usually lead to a significant erosion of enantiopurity by base-mediated epimerization35, the procedure reported herein produced the desired olefin 7 with minimal loss of chiral information.

Mechanistic experiments

Finally, we performed control experiments to propose a reasonable mechanism. N-iminyl aziridine 9 (generally prepared and used in situ throughout this manuscript) was isolated and subjected to specific conditions: upon heating 9 to 90 °C in toluene, in presence of catalytic Rh2(OAc)4, cyclopropane 10 was isolated in 90% yield (Fig. 6a). When the reaction is performed in DMSO, benzophenone is obtained in 43% yield (Fig. 6b)36. These results provide evidence for the formation of a diazo compound through cheletropic elimination. Further proof of a concerted cheletropic elimination can be inferred from the high sterospecificity of the reaction. Pure samples of either cis or trans-aziridine were subjected to the reaction conditions, delivering respectively pure Z (Fig. 6c) or E (Fig. 6d) olefin as product. Finally, a different nucleophile for the aziridine formation was used, namely triethyl sulfonium iodide, and a different ratio in the double-bond geometry was obtained (Fig. 6e). Since the aziridine eventually formed would be the same for the two different nucleophiles, and the cheletropic reversion from the latter is stereospecific, a different ratio in the olefin product geometry hints at the fact that the nucleophilic attack on the azine is the stereo-determining step.

Based on these experiments, we are able to propose a working mechanism for the reaction (Fig. 7). Starting from the azine (2d), an initial nucleophilic attack of the sulfoxonium ylide on the aldimine carbon delivers a zwitterionic compound, which then quickly collapses in an intramolecular fashion to form the aziridine with extrusion of a sulfoxide molecule. This is the key stereo-determining moment: two possible faces of attack are feasible, aziridine formation via I would deliver a cis three-membered ring II while an attack via III would deliver trans three-membered ring IV. Moreover, the formed aziridines are stable and not prone to geometric interconversion37, 38. At this stage is not possible to state the factors leading to a preference for attack on one of the two faces, most probably subtle stereoelectronic factors are playing a role. Eventually, the aziridine, when heated cycloreverts to unveil the desired olefin in a concerted mechanism and in a stereo-specific manner. A two-step ionic mechanism of degradation via V is operating at the same time leading to a homologated compound VI. Anyway, this is not a reversible process as no geometry swapping is observed.

In conclusion, we have developed a new concept for carbonyl olefination, relying on formation of a three-membered ring as key intermediate. This intermediate, an N-iminyl aziridine, is conveniently accessed in a one-pot procedure by addition of a sulfoxonium ylide to an azine, the thermal decomposition of which leads to formation of the desired olefin in good to high yields. Notably, this methodology selectively delivers trans-disubstituted olefins and affords dienes from α,β-unsaturated carbonyls, in contrast to the usual selectivity of sulfoxonium ylides. Importantly, α-chiral aldehydes can be olefinated with minimal epimerization. While we are well aware of the power and historical weight of the venerable Wittig, Julia, Peterson, Tebbe, and related olefination procedures, developed continuously over the past 60 years, we believe that the approach reported herein has significant complementarity to these methods.

Methods

Representative procedure for the olefination reaction

Method A: A mixture of aldehyde (1.0 equiv.) and hydrazone 1a (1.1 equiv.) was stirred in the presence of MgSO4 (100 mg/mmol) in MeOH at 60 °C overnight. Then, the reaction mixture was filtered and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. In another flask, potassium tert-butoxide (2.0 equiv.) was added to a solution of trimethyl sulfoxonium iodide (2.5 equiv.) in MeCN (0.2 M). The resulting mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature. To this solution was added the previously formed azine in MeCN (0.2 M) and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature until complete conversion (usually 3–6 h). Toluene (0.2 M) was then added and the reaction mixture was heated to 90 °C overnight. The reaction was then diluted with a saturated aqueous solution of NH4Cl and extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel to afford the desired product.

Method B: A mixture of aldehyde (1.0 equiv.) and hydrazone 1b (1.1 equiv.) was stirred in the presence of MgSO4 (100 mg/mmol) in CH2Cl2 (0.3 M) at room temperature for 30 min. Then, the reaction mixture was filtered and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. In a pressure vial, potassium tert-butoxide (1.5 equiv.) was added to a solution of trimethyl sulfoxonium iodide (1.75 equiv.) in MeCN (0.3 M). The resulting mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature. To this solution was added the previously formed azine in MeCN (1 M) and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature until complete conversion. At completion of the reaction, the volatiles were removed under reduced pressure and the solid residues were diluted with toluene (0.5 M) and heated to 150 °C. After 24 h, the reaction is generally complete and the mixture is cooled to room temperature. The solution is then diluted with aqueous NH4Cl and extracted with EtOAc (3×). The combined organic layers were washed with brine and dried over MgSO4. The crude product is then purified via flash chromatography on silica gel to afford the desired product.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information Files.

References

Patai, S. The Chemistry of Alkenes in the Chemistry of the Functional Groups (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New Jersey, 1964).

Beletskaya, I. P. & Cheprakov, A. V. The Heck reaction as a sharpening stone of palladium catalysis. Chem. Rev. 100, 3009–3066 (2000).

Grubbs, R. H. Olefin metathesis. Tetrahedron 60, 7117–7140 (2011).

Kolb, H. C., Van Nieuwenhze, M. S. & Sharpless, K. B. Catalytic asymmetric dihydroxylation. Chem. Rev. 94, 2483–2547 (1994).

Blakemore, P. R. Olefination of Carbonyl Compounds by Main-Group Element Mediators, In: Knochel P., Molander G. A., editors. Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. 2nd ed. Vol. 1 (Elsevier Ltd., Oxford, 2014).

Takeda, T. Modern Carbonyl Olefination: Methods and Applications, 1st ed. (Wiley‒VCH, Weinheim, 2004).

Wittig, G. & Geissler, G. Zur Reaktionsweise des pentaphenyl-phosphors und einiger derivate. Liebigs Ann. 580, 44–157 (1953).

Peterson, D. J. Carbonyl olefination reaction using silyl-substituted organometallic compounds. J. Org. Chem. 33, 780–784 (1968).

Baudin, J. B., Hareau, G., Julia, S. A. & Ruel, O. A direct synthesis of olefins by reaction of carbonyl compounds with lithio derivatives of 2-[alkyl- or (2′-alkenyl)- or benzyl-sulfonyl]-benzothiazoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 32, 1175–1178 (1991).

Tebbe, F. N., Parshall, G. W. & Reddy, G. S. Olefin homologation with titanium methylene compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 100, 3611–3613 (1978).

Horner, L., Hoffmann, H. & Wippel, H. G. Phosphororganische Verbindungen, XII. Phosphinoxyde als olefinierungsreagenzien. Chem. Ber. 91, 61–63 (1958).

O’Brien, C. J. et al. Recycling the waste: the development of a catalytic Wittig reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 6836–6839 (2009).

Coyle, E. E. et al. Catalytic Wittig reactions of semi- and nonstabilized ylides enabled by ylide tuning. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 12907–12911 (2014).

Wu, Z. et al. Stereospecific synthesis of alkenes by eliminative cross-coupling of enantioenriched sp3-hybridized carbenoids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 12285–12289 (2016).

Dong, D. J., Li, H. H. & Tian, S. K. A highly tunable stereoselective olefination of semistabilized triphenylphosphonium ylides with N-sulfonyl imines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 5018–5020 (2010).

Fang, F., Li, Y. & Tian, S. K. Stereoselective olefination of N-sulfonyl imines with stabilized phosphonium ylides for the synthesis of electron-deficient alkenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 1084–1091 (2011).

Taylor, R. J. K. & Casy, G. The Ramberg-Bäcklund reaction. Org. React. 62, 357–475 (2004).

Wang, Z. Barton-Kellogg olefination. Comprehensive organic name reactions and reagents. (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New Jersey, 2010).

Ter Wiel, M. K. J., Vicario, J., Davey, S. G., Meetsma, A. & Feringa, B. L. New procedure for the preparation of highly sterically hindered alkenes using a hypervalent iodine reagent. Org. Biomol. Chem. 3, 28–30 (2005).

Ireland, C. J. & Pizey, J. S. A new synthesis of tetra-substituted ethylenes. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1, 4–5 (1972).

Luparia, M., Oliveira, M. T., Audisio, D., Frébault, F. & Maulide, N. Catalytic asymmetric diastereodivergent deracemisation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 12631–12635 (2011).

Madelaine, C., Valerio, V. & Maulide, N. Unexpected electrophilic rearrangements of amides: a stereoselective entry to challengingly substituted lactones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 1583–1586 (2010).

Felix, D. et al. α,β-Epoxyketon→Alkinon-Fragmentierung II: Pyrolytischer Zerfall der Hydrazone aus α,β-Epoxyketonen und N-amino-aziridinen. Über synthetische Methoden, 4. Mitteilung Helv. Chem. Acta 55, 1276–1319 (1972).

Müller, R. K., Felix, D., Schreiber, J. & Eschenmoser, A. Zur Stereochemie der thermischen Fragmentierung von Hydrazonderivaten substituierter N-Amino-aziridine.Helv. Chem. Acta 53, 1479–1484 (1970).

Nicolaides, A. et al. The elusive benzocyclobutenylidene: a combined computational and experimental attempt. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 2870–2876 (2001).

Chen, N., Jones, M. Jr, White, W. R. & Platz, M. S. Equilibrium between homocub-1(9)-ene and homocub-9-ylidene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 4981–4992 (1991).

Kirmse, W., Krzossa, B. & Steenken, S. Biphotonic generation of carbenes and carbocations by laser flash photolysis. Tetrahedron Lett. 37, 1197–1200 (1996).

Lee, H. Y., Kim, D. I. & Kim, S. Tandem radical cyclization reaction of N-aziridinyl imines to [3.3.3]propellanes: formal total syntheses of dl-modhephene. Chem. Commun. 13, 1539–1540 (1996).

Tewari, R. S., Awasthi, A. K. & Awasthi, A. Phase-transfer catalyzed synthesis of 1,2-disubstituted aziridines from sulfuranes and Schiff base or aldehyde arylhydrazones. Synthesis 4, 330–333 (1983).

Aggarwal, V. K., Thompson, A., Jones, R. V. H. & Standen, M. C. H. Catalytic and asymmetric aziridination using sulfur ylides. Phosphorous Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 120, 361–362 (1997).

Woodward, R. B. & Hoffmann, R. The conservation of orbital symmetry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 8, 781–853 (1969).

Aggarwal, V. K. & Winn, C. L. Catalytic asymmetric sulfur ylide-mediated epoxidation of carbonyl compounds: scope, selectivity, and applications in synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 37, 611–620 (2004).

Gololobov, Y. G., Nesmeyanov, A. N., Iysenko, V. P. & Boldeskul, I. E. Twenty-five years of dimethylsulfoxonium ethylide(Corey’s reagent). Tetrahedron 43, 2609–2651 (1987).

Clark, R. D. & Helmkamp, G. K. Stereochemistry of the deamination of aziridines. J. Org. Chem. 29, 1316–1320 (1964).

Lebel, H. & Paquet, V. Rhodium-catalyzed methylenation of aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 320–328 (2004).

O´Connor, N. R., Bolgar, P. & Stoltz, B. M. Development of a simple system for the oxidation of electron-rich diazo compounds to ketones. Tetrahedron Lett. 57, 849–851 (2016).

Metzger, V. H. & Seelert, K. Die Umsetzung von Benzalanilin mit Dimethyl-oxo-sulfoniummethylid. Z. Naturforschg. 18b, 335–336 (1963).

Metzger, V. H. & Seelert, K. Über die Umsetzung von Benzaldazin mit Dimethyl-oxo-sulfoniummethylid. Z. Naturforschg. 18b, 336 (1963).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the University of Vienna for continued support of our research. Financial support by the European Research Council (StG 278872 FLATOUT), the DFG, and Covestro AG is acknowledged

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.M. and S.N. conceived and designed the research. S.N., A.O., and P.A. carried out experiments. N.M., S.N., A.O., and P.A. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niyomchon, S., Oppedisano, A., Aillard, P. et al. A three-membered ring approach to carbonyl olefination. Nat Commun 8, 1091 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01036-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01036-y

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.