Abstract

The efficient transformation of CO2 into chemicals and fuels is a key challenge for the decarbonisation of the synthetic production chain. Formic acid (FA) represents the first product of CO2 hydrogenation and can be a precursor of higher added value products or employed as a hydrogen storage vector. Bases are typically required to overcome thermodynamic barriers in the synthesis of FA, generating waste and requiring post-processing of the formate salts. The employment of buffers can overcome these limitations, but their catalytic performance has so far been modest. Here, we present a methodology utilising IL as buffers to catalytically transform CO2 into FA with very high efficiency and comparable performance to the base-assisted systems. The combination of multifunctional basic ionic liquids and catalyst design enables the synthesis of FA with very high catalytic efficiency in TONs of >8*105 and TOFs > 2.1*104 h−1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Formic acid (FA) is an important basic chemical, is currently being discussed as a promising candidate for hydrogen storage and can potentially be upgraded to higher added value CO2 synthetic products1,2,3. Unfortunately, to date its synthesis is based on the indirect water carbonylation, using CO generated from fossil fuels4. Without a doubt a system using the greenhouse gas CO2 as a carbon source would be environmentally preferential, if the hydrogen used for these transformation is generated from renewable resources. However, the direct hydrogenation of CO2 is thermodynamically unfavourable5. Bases are commonly added to reaction mixture to shift the thermodynamic equilibrium by the consecutive consumption of FA in an acid–base reaction to the product side5,6,7.

However, an important limitation of these approaches is the formation of formate adducts and salts, which would need to be tediously purified in the consecutive steps with acids, which adds to the cost and the amount of waste generated6,8. Therefore, the direct hydrogenation of CO2 would be preferential. Unfortunately, the hydrogenation is in gas phase thermodynamically unfeasible5. Alternatively, the reaction can be undertaken in the absence of bases utilising basic properties of solvents applied during the hydrogenation9,10,11,12,13,14,15. However, in the absence of strong bases the reaction is thermodynamically and kinetically difficult to operate5. As a consequence, considerably fewer systems have been reported for the hydrogenation of CO2 to FA under base-free conditions. Furthermore, these systems typically operate under very high pressures9 and the catalytic activity and concentration of FA achieved are significantly lower than under basic conditions10,11,12,13,14,15.

We have recently demonstrated that basic ionic liquids can effectively buffer the reaction, therefore acting as very mild bases that shift the thermodynamic equilibrium to the product side, whilst stabilising the catalytically active species at low partial pressure of H2 and CO216. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that buffering ILs can be immobilised onto supported phases, thus facilitating the separation of the FA at the end of the process following a supported ionic liquid approach17,18,19,20. In our previous studies we have established the thermodynamic parameters for this transformation employing basic ILs, and therefore we can understand the maximum concentration of FA achievable as a function of the reaction conditions16. Furthermore, we previously studied the effect of ligand modifications onto the hydrogenation of CO2 in the presence of ILs. Key parameters effecting the catalyst activity and stability were associated with the electron density at the metal centre and the resistance of the catalyst towards protonation21.

Here, we present a catalytic system for the hydrogenation of CO2 under buffering conditions specifically designed to work under a wide range of temperatures. This enables optimising the catalyst performance by pushing the conditions to the thermodynamic limitations imposed by the reaction and consequently balancing kinetic and thermodynamic performance and achieving high catalytic efficiency. The robustness of the catalyst enables the addition of lewis acids, which increases the performance of the catalyst in terms of activity and stability. The results obtained here are comparable to those reported with systems containing stronger bases and represents an important leap forward towards sustainable systems to transform CO2.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of catalyst

The design of the catalysts plays a key role in the development of efficient catalytic systems. Very recently, it has been demonstrated that basic ionic liquids provide a buffering environment that enables the efficient synthesis of FA, but with much lower enthalpy than when a base (leading to a salt formation) is employed16,22. Under these conditions, optimal electrondonation properties of the ligand are key to balance reactivity and the resistance to deactivation via protonation of the catalyst (Fig. 1). Furthermore, complexes with high chemical and thermal stability lead to catalysts with large operational windows and an increased compatibility with other components, such as co-catalysts. NHC-based pincer architectures fulfil all these criteria, hence being ideal candidates for this transformation23. Furthermore, pincer ligand architecture have already been demonstrated to be active in the hydrogenation of CO2. However, pincers normally exhibit a co-operative mechanism in the activation of hydrogen24,25, which leads to the deactivation of the catalyst (Fig. 1, substrate poisoning)26. Consequently, a suitable catalyst should prevent the coordination of substrates in undesired positions. In this study, this was achieved by a direct connection of the aromatic pyridine with the imidazole side arms.

The molecular catalyst (centre) should be resistant to deactivation by the substrates (top), tune the electrondonation of the ligand to the metal centre to balance stability and activity (left), resist the increasingly acidic media and strong reductive conditions (right) and be compatible with other catalysts (bottom).

The silver transmetalation route employing [Ru(CO)2(Cl)2]n as the Ru source, and L-1 as the ligand was chosen to synthesise the desired Ru–CNC complex (Fig. 2). The reaction was followed by the disappearing signal for the C2–H in the 1H-NMR spectra and the appearance of a new peak at 181 ppm in the 13C spectra (see Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). In the IR spectra two significant bands at 1993 and 2051 cm−1 (see Supplementary Fig. 3), corresponding to two asymmetric CO stretching vibrations can be observed. The general structure was confirmed with single X-ray crystal analysis. Minor scrambling is observed with Cl− bond to Ru, i.e. replacement of Br−. In a similar fashion the counterion distributed 1:1 (Br:Cl), giving an overall molecular sum formula of C21H25Br0.63Cl1.29N5O2Ru. The major halide bond to the metal centre was chloride, as confirmed with ESI-ms. The analysis gave a mass of 516m/z and a minor product with 562m/z (see Supplementary Fig. 4). The analogous complex consisting solely of Cl counterions was synthesised as a control experiment to rule out the influence of multiple halides. The exchange of counterions in L-1 to Cl employing an ion exchange resin yielded the ligand L-1(Cl) (Supplementary Fig. 5), though at significantly reduced yields compared to 1 (see “Methods” section for more details). The formation of the carbene complex following the same procedure employed for the synthesis of 1, yields 1-Cl at significantly lower yield. The complex was characterised by ESI-ms, where 1-Cl displayed a sole peak at 516m/z (see Supplementary Fig. 6), whereas identical NMR shifts were observed compared to 1.

The single crystal analysis of 1 (Supplementary Fig. 7) indicated an average molecular mass of 578.11 g/mol, distributing to complexes with the sum formulas of C21H25Cl2N5O2Ru and C21H25BrClN5O2Ru. This in bromide to chloride ratio of 30:70. Indeed, the observed mass peaks for the M-Cl+ to M-Br+ of ca. 73:27 indicate that the ratio determined by single crystal analysis is valid. Further evidence for this ratio was found by ICP-OES analysis. Here a Ru content of 19.2 mg L−1 was found in a 0.199 mM solution (for 100% Cl expected Ru content is 20.8 mg L−1 and for 100% Br expected Ru content is 18.2 mg L−1), which indicate a molar ratio between Br−:Cl− of 70:30. In this way a molecular mass of 578.11 g/mol was used to determine the amount of catalyst in solution. Furthermore, neither the addition of Cl− or Br− showed a difference in catalytic activity or stability in comparison to the non-modified system, indicating that the halide plays an insignificant role onto the catalytic activity.

Catalytic efficiency evaluation

In an initial screening of catalytic activity, it was observed that 1 (0.28 mM) achieves a concentration of 0.5 M solution of FA at 80 °C in DMSO:water (5 v/v% water) in the presence of 1-butyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium acetate (BMMI.OAc) under 60 bar pressure (H2:CO2 = 1:1). Furthermore, in the absence of catalyst we do not observe any conversion under elsewise identical reaction conditions (6 mL DMSO:H2O, 3.3 mmol BMMI.OAc, with PH2 = PCO2 = 30 bar at 80 °C). According to the thermodynamic parameters previously calculated for this system16, the concentration of FA observed is close to the thermodynamic equilibrium at ~120 °C (see Supplementary Fig. 8). Above 80 °C the decomposition of DMSO was observed. Fortunately, when BMMI.OAc is employed as an additive the reaction can be performed in a broad range of solvents16. In dioxane:H2O the catalytic system achieves similar concentration of FA at 80 and 100 °C as in DMSO at 80 °C (0.5 M at 100 °C in dioxane:H2O and 0.5 M in DMSO:H2O). Note also that the temperature range employed did not lead to a decomposition of the IL, as evidenced by NMR spectroscopy provided in Supplementary Fig. 9.

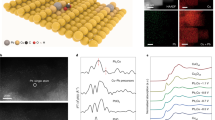

In order to investigate the thermal stability of the catalyst we investigated the reaction mixture towards the formation of nanoparticles during the reaction. It is important to note that no evidence of nanoparticle formation was observed under the reaction conditions assayed, even when a relatively high concentration of catalyst (0.28 mM) was employed. Even at high temperatures and pressures (120 °C, 60 bar (PH2 = PCO2)), TEM and DLS analysis showed no evidence of nanoparticles (see ESI for more details). Furthermore, the catalyst was not active in a reaction typically catalysed by Ru nanoparticles27,28,29,30,31, such as the hydrogenation of benzene at 120 °C under 50 bar H2 in the presence of BMMI.OAc even when high catalyst loadings are used, see SI for more details.

In the next step the catalyst activity and stability were explored. For this purpose, we lowered the concentration of catalyst (from 0.28 mM to 2.8 µM) and measured the TOFini after 4 h of reaction as an average value. We found that increasing the temperature led to an increase in the measurable TOFini after 4 h, at the expense of a lower achievable concentration of FA (and consequently TON) at temperatures above 120 °C (see Table 1 entries 5 and 6). This is due to the thermodynamic limitations of the system as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 8 in the Supporting information.

Interestingly, the nature of the halide in 1, does not influence the catalytic activity observed. The compound 1-Cl was tested under identical conditions than 1 as a control experiment, which showed the same catalytic activity in terms of TON and TOF (Table 1 entries 4 and 6). This suggests that the halide coordinated to the active Ru centre represents the leaving group and the catalytic activity is mainly influenced by the carbene pincer ligand employed.

Plotting the concentration of FA generated after 72 h (Fig. 3a) allows for a better understanding of the efficiency of the catalytic system. Here a maximum concentration of FA can be observed at 120 °C. Below that temperature, the system is controlled by kinetic limitations of the catalyst, whilst at higher temperatures the reaction is limited by approaching the thermodynamic equilibrium inherent to the reaction under the studied conditions. Our previous report shows the thermodynamic equilibrium curve calculated employing Van’t Hoff plots for the CO2 hydrogenation to FA employing BMMI.OAc as a buffering system (see Supplementary Fig. 8)16.

In the next step the effect of pressure was investigated. Here a linear correlation in between the achieved concentration of FA and pressure can be observed (Fig. 3b). This is in consistence with the Henry’s law, which predicts a linear relationship between the amount of dissolved gas and the pressure.

Mechanistically, the hydrogenation of CO2 to FA can be divided into two main steps. In the first step, a hydride is transferred onto CO2. In the second step, H2 is activated releasing a proton and formate, with a simultaneous regeneration of the active hydride (Fig. 4a). In order to determine the rate-determining step, various gas compositions were tested (maintaining constant the total pressure). The observed reaction rate decreased significantly at low partial pressure of CO2 (Fig. 4b). Indeed, at 20 bar CO2 and 40 bar H2 a TOFini of 2700 h−1 was obtained. On the contrary an increased partial pressure of CO2 led to increased rates, i.e. at 45 bar CO2 and 15 bar H2 a TOFini of 9700 h−1 is determined, (cf. 4360 h−1 at PCO2 = PH2 = 30 bar). These experiments clearly show a strong dependence on CO2, thus indicating the CO2 insertion to be the rate-determining step.

An activation energy of 93 ± 7 kJ mol−1 was determined from the Arrhenius plot (Fig. 4c). The activation energy can either be decreased by increasing the electron donation onto the metal, leading to a more nucleophilic hydride, thus decreasing the hydricity (\({{\Delta }}G_{{\mathrm{{H}}}^ - }\))32. Based on our recent study21, a low hydricity will ultimately lead to a more nucleophilic/basic hydride, rendering the catalyst prone protonation and hence deactivation.

It has been demonstrated that charged intermediates and transition state formed during the CO2 insertion can be stabilised with Lewis acids (see Supplementary Fig. 10 for a suggested mechanism)33,34,35,36. Therefore Sc(OTf)3 was tested due to its high solubility in organic solvents, tolerance towards water and due to its relatively weak acidic nature37. It was found that Sc(OTf)3 significantly increased the reaction rate. However, smaller amounts have only a minor effect on the rate (Fig. 4d). At an optimal concentration of 20 mM for Sc(OTf)3 was found a TOFini of 21,200 h−1, which corresponds to 4.9 times the activity without using the lewis acid. Above this concentration a drop in rate was observed, presumably due to catalyst poisoning as already observed in previous studies38. However, in the presence of Sc(OTf)3 the concentration of FA generated decreased slightly to 0.32 M, yielding a TON of 114,400 (Table 2, entry 2). Increasing the hydrogen to carbon dioxide ratio did not show any pronounced effects on activity nor stability (Table 2, entry 3). Under these conditions, the amount of catalyst was reduced to 1.7 nmol, which led to an unprecedented TON of 833,800, while the TOFini was maintained at 20,600 h−1 (Table 3, entry 4). In this case, there is no conversion without BMMI.OAc or with Sc(OTf)3 only as catalyst.

It is worth noting the remarkable activity and stability of our catalytic system, which shows ca. 50 times higher value in TON and 23 times higher value in TOFini in the hydrogenation of CO2 to FA under buffering conditions than the best reported to date9,10,11,14,16. Furthermore, the TON and TOFini towards FA are comparable to values obtained under basic conditions39,40,41. Interestingly, the CNC–Ru pincer reported here outperforms its previously reported analogue with a six-membered bite angle ring, even though the previous complex was reported to operate under basic conditions42.

To conclude, we have presented a catalytic system capable of highly efficiently transform CO2 into FA under buffering conditions. The combination of basic ionic liquids, highly robust catalysts based on Ru pincer N-heterocyclic carbenes and Lewis acid catalysts showed high efficiency at elevated temperatures, balancing kinetic and thermodynamic performance. The catalytic activity observed is the highest observed to date for base-free systems and comparable to literature reports employing basic conditions that lead to the formation of thermodynamically stable formate salts. This work will open new avenues in the hydrogenation of CO2 to chemicals and for the storage of hydrogen in liquid energy vectors.

Methods

General information

The ionic liquids 1,2-dimethyl-3-butylimidazolium acetate (BMMI.OAc) were prepared from literature methods43. [Ru(Cl)2(CO)2]n complex was synthesised according to a reported method44. 1,2-dimethylimidazole was purchased from IOLITEC while n-chlorobutane, dimethylsulfoxide, Sc(OTf)3 and deuterated dimethylsulfoxide were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. Dioxane and ethylene glycol was provided by VWR. RuCl3·xH2O was provided by Precious Metals Online. All the ILs were placed under vacuum at 50 °C for 2–3 h prior to use. NMR measurements were performed on a 400 MHz Bruker or 500 MHz Bruker with d1 = 50 s and ESI-MS analysis was performed on a Bruker microTOFII.

Synthesis of 2,6-bis(1-butylimidazolium)pyridine dibromide

2,6-bis(1-butylimidazolium)pyridine dibromide was prepared according to a previously reported method45. 3.36 g (27 mmol, 2 eq) 1-butylimidazole and 3.2 g (13.5 mmol, 1 eq) 2,6-dibromopyridine are stirred at 150 °C for 72 h under argon. After cooling the reaction mixture to room temperature, the reaction mixture was dissolved in CHCl3 and precipitated with Et2O. The desired product is isolated as a white solid after repetitive precipitation from MeOH with Et2O. Yield: 4.1 g (8.37 mmol, 62%). 1H-NMR and 13C spectra match previously reported results43.

Synthesis of 2,6-bis(1-butylimidazolium)pyridine dichloride

2,6-bis(1-butylimidazolium)pyridine dichloride was prepared by using amberlite 402 (Cl form) ion exchange resin. 2 g (4.1 mmol) 2,6-bis(1-butylimidazolium)pyridine dibromide was dissolved in a small amount of water and passed through an ion exchange column containing 50 g amberlite 402 (Cl form) ion exchange resin using water as the eluent. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the product is obtained upon dissolving the crude product in 5 mL MeOH and precipitation with Et2O. The product is obtained as a white powder.

Yield: 1 g (2.5 mmol, 61%)

Synthesis of Ru–CNC pincer

In the dark under argon: 700 mg (1.55 mmol, 1 eq) 2,6-bis(1-butylimidazolium)pyridine dibromide and 400 mg (1.73 mmol, 1.12 eq) Ag2O are dissolved in 10 mL dry and degassed DCM. The reaction mixture is stirred in the dark under an argon atmosphere for 24 h. Afterwards the solution is filtered through a celite pad, the solvent is removed in vacuum. The resulting white solid is washed with 3 × 15 mL Et2O. The resulting white solid is directly used for the next step.

908 mg of the white precipitate obtained in the previous step and 300 mg (1.30 mmol, 1 eq) [Ru(CO)2(Cl)2] are mixed in 20 mL THF and the suspension is stirred under argon in the dark for 48 h at 55 °C. The resulting reaction mixture is cooled to room temperature and filtered through a short celite pad and reduced under vacuum. The resulting yellow solid is re-dissolved in 5 mL MeOH and filtered. The product is obtained upon precipitation with Et2O and finally washed with MeCN. Crystals are obtained by slow diffusion of Et2O into MeOH (see supplementary information for more details on the crystal structure). Yield: 350 mg (0.61 mmol, 47%). CHN: found: 11.3% N, 42.0% C, 4.7% H; expected: 12.1% N, 43.6% C, 4.4% H. Sum formula C21H25Br0.6Cl1.4N5O2Ru. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ 8.67 ppm (d, 3J = 2.24 Hz, 2H), 8.62 ppm (t, 3J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.18 ppm (d, 3J = 8.24 Hz, 2H), 7.91 ppm (2 H, 3J = 2.20 Hz, 2H), 4.52–5.13 ppm (m, 4H), 1.89 ppm (p, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 1.58–1.22 ppm (m, 4H), 0.95 ppm (t, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 6H). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6, 126 MHz): δ 181, 151, 125, 120, 119, 109, 52, 33, 20, 14 ppm. ESI-ms: 592m/z. ATR-IR: υ [cm−1]: 3200 (C–Harom), 3000 (C–HIm), 2900 (C–Hal), 2051 (C=O), 1993 (C=O).

Synthesis of Ru–CNC pincer Cl form

In the dark under argon: 614 mg (1.55 mmol, 1 eq) 2,6-bis(1-butylimidazolium)pyridine dichloride and 400 mg (1.73 mmol, 1.12 eq) Ag2O are dissolved in 10 mL dry and degassed DCM. The reaction mixture is stirred in the dark under an argon atmosphere for 24 h. Afterwards the solution is filtered through a celite pad, the solvent is removed in vacuum. 300 mg (1.30 mmol, 0.8 eq) [Ru(CO)2(Cl)2] are mixed in 20 mL THF and the suspension is stirred under argon in the dark for 48 h at 55 °C. The resulting reaction mixture is cooled to room temperature and filtered through a short celite pad and reduced under vacuum. The resulting yellow solid is re-dissolved in 5 mL MeOH and filtered. The product is obtained upon precipitation with Et2O and finally washed with MeCN. Yield: 52 mg (0.09 mmol, 6%). Sum formula C21H25Cl2N5O2Ru. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ 8.67 ppm (d, 3J = 2.24 Hz, 2H), 8.62 ppm (t, 3J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.18 ppm (d, 3J = 8.24 Hz, 2H), 7.91 ppm (2 H, 3J = 2.20 Hz, 2H), 4.52–5.13 ppm (m, 4H), 1.89 ppm (p, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 1.58–1.22 ppm (m, 4H), 0.95 ppm (t, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 6H). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6, 126 MHz): δ 181, 151, 125, 120, 119, 109, 52, 33, 20, 14 ppm. ESI-ms: 516m/z.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Loges, B., Boddien, A., Junge, H. & Beller, M. Controlled generation of hydrogen from formic acid amine adducts at room temperature and application in H2/O2 fuel cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 3962–3965 (2008).

Loges, B., Boddien, A., Gärtner, F., Junge, H. & Beller, M. Catalytic generation of hydrogen from formic acid and its derivatives: useful hydrogen storage materials. Top. Catal. 53, 902–914 (2010).

Mellmann, D., Sponholz, P., Junge, H. & Beller, M. Formic acid as a hydrogen storage material—development of homogeneous catalysts for selective hydrogen release. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 3954–3988 (2016).

Reutemann, W. & Kieczka, H. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, 2000).

Klankermayer, J., Wesselbaum, S., Beydoun, K. & Leitner, W. Selective catalytic synthesis using the combination of carbon dioxide and hydrogen: catalytic chess at the interface of energy and chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 7296–7343 (2016).

Schaub, T. & Paciello, R. A. A process for the synthesis of formic acid by CO2 hydrogenation: thermodynamic aspects and the role of CO. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 7278–7282 (2011).

Leitner, W. Carbon dioxide as a raw material: the synthesis of formic acid and its derivatives from CO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 34, 2207–2221 (1995).

Wesselbaum, S., Hintermair, U. & Leitner, W. Continuous-flow hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to pure formic acid using an integrated scCO2 process with immobilized catalyst and base. Angew. Chem. 124, 8713–8716 (2012).

Rohmann, K. et al. Hydrogenation of CO2 to formic acid with a highly active ruthenium acriphos complex in DMSO and DMSO/water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 8966–8969 (2016).

Moret, S., Dyson, P. J. & Laurenczy, G. Direct synthesis of formic acid from carbon dioxide by hydrogenation in acidic media. Nat. Commun. 5, 4017 (2014).

Sahoo, A. R. et al. Phosphine-pyridonate ligands containing octahedral ruthenium complexes: access to esters and formic acid. Catal. Sci. Technol. 7, 3492–3498 (2017).

Hayashi, H., Ogo, S. & Fukuzumi, S. Aqueous hydrogenation of carbon dioxide catalysed by water-soluble ruthenium aqua complexes under acidic conditions. Chem. Commun. 2714–2715 (2004).

Ogo, S., Kabe, R., Hayashi, H., Harada, R. & Fukuzumi, S. Mechanistic investigation of CO2 hydrogenation by Ru(ii) and Ir(iii) aqua complexes under acidic conditions: two catalytic systems differing in the nature of the rate determining step. Dalton Trans. 4657–4663 (2006).

Lu, S.-M., Wang, Z., Li, J., Xiao, J. & Li, C. Base-free hydrogenation of CO2 to formic acid in water with an iridium complex bearing a N,N[prime or minute]-diimine ligand. Green Chem. 18, 4553–4558 (2016).

Zhao, G. & Joó, F. Free formic acid by hydrogenation of carbon dioxide in sodium formate solutions. Catal. Commun. 14, 74–76 (2011).

Weilhard, A., Qadir, M. I., Sans, V. & Dupont, J. Selective CO2 hydrogenation to formic acid with multifunctional ionic liquids. ACS Catal. 8, 1628–1634 (2018).

Hauzenberger, C. et al. Continuous conversion of carbon dioxide to propylene carbonate with supported ionic liquids. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 13131–13139 (2018).

Logemann, M. et al. Continuous gas-phase hydroformylation of but-1-ene in a membrane reactor by supported liquid-phase (SLP) catalysis. Green Chem. 22, 5691–5700 (2020).

Riisager, A. et al. Very stable and highly regioselective supported ionic-liquid-phase (SILP) catalysis: continuous-flow fixed-bed hydroformylation of propene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 815–819 (2005).

Mehnert, C. P., Mozeleski, E. J. & Cook, R. A. Supported ionic liquid catalysis investigated for hydrogenation reactions. Chem. Commun. 24, 3010–3011 (2002).

Weilhard, A., Salzmann, K., Dupont, J., Albrecht, M. & Sans, V. Catalyst design for highly efficient carbon dioxide hydrogenation to formic acid under buffering conditions to formic acid. J. Catal. 385, 1–9 (2020).

Qadir, M. I. et al. Selective carbon dioxide hydrogenation driven by ferromagnetic RuFe nanoparticles in ionic liquids. ACS Catal. 8, 1621–1627 (2018).

Peris, E. Smart N-heterocyclic carbene ligands in catalysis. Chem. Rev. 118, 9988–10031 (2018).

Zell, T. & Milstein, D. Hydrogenation and dehydrogenation iron pincer catalysts capable of metal–ligand cooperation by aromatization/dearomatization. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 1979–1994 (2015).

Friedrich, A., Drees, M., Käss, M., Herdtweck, E. & Schneider, S. Ruthenium complexes with cooperative PNP-pincer amine, amido, imine, and enamido ligands: facile ligand backbone functionalization processes. Inorg. Chem. 49, 5482–5494 (2010).

Filonenko, G. A., Hensen, E. J. M. & Pidko, E. A. Mechanism of CO2 hydrogenation to formates by homogeneous Ru–PNP pincer catalyst: from a theoretical description to performance optimization. Catal. Sci. Technol. 4, 3474–3485 (2014).

Leal, B. C., Consorti, C. S., Machado, G. & Dupont, J. Palladium metal nanoparticles stabilized by ionophilic ligands in ionic liquids: synthesis and application in hydrogenation reactions. Catal. Sci. Technol. 5, 903–909 (2015).

Weilhard, A. et al. Challenging thermodynamics: hydrogenation of benzene to 1,3-cyclohexadiene by Ru@Pt nanoparticles. ChemCatChem 9, 204–211 (2016).

Dyson, P. J. Arene hydrogenation by homogeneous catalysts: fact or fiction? Dalton Trans. 2964–2974 (2003).

Martínez-Prieto, L. M. & Chaudret, B. Organometallic ruthenium nanoparticles: synthesis, surface chemistry, and insights into ligand coordination. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 376–384 (2018).

Chacón, G. & Dupont, J. Arene hydrogenation by metal nanoparticles in ionic liquids. ChemCatChem 11, 333–341 (2019).

Jeletic, M. S. et al. Understanding the relationship between kinetics and thermodynamics in CO2 hydrogenation catalysis. ACS Catal. 7, 6008–6017 (2017).

Spentzos, A. Z., Barnes, C. L. & Bernskoetter, W. H. Effective pincer cobalt precatalysts for lewis acid assisted CO2 hydrogenation. Inorg. Chem. 55, 8225–8233 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Iron catalyzed CO2 hydrogenation to formate enhanced by Lewis acid co-catalysts. Chem. Sci. 6, 4291–4299 (2015).

Bernskoetter, W. H. & Hazari, N. Reversible hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to formic acid and methanol: Lewis acid enhancement of base metal catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 1049–1058 (2017).

Heimann, J. E., Bernskoetter, W. H., Hazari, N. & Mayer, J. M. Acceleration of CO2 insertion into metal hydrides: ligand, Lewis acid, and solvent effects on reaction kinetics. Chem. Sci. 9, 6629–6638 (2018).

Kobayashi, S. Scandium triflate in organic synthesis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 15–27 (1999).

Huff, C. A. & Sanford, M. S. Cascade catalysis for the homogeneous hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 18122–18125 (2011).

Schmeier, T. J., Dobereiner, G. E., Crabtree, R. H. & Hazari, N. Secondary coordination sphere interactions facilitate the insertion step in an iridium(III) CO2 reduction catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 9274–9277 (2011).

Tanaka, R., Yamashita, M. & Nozaki, K. Catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide using Ir(III)−pincer complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 14168–14169 (2009).

Filonenko, G. A., van Putten, R., Schulpen, E. N., Hensen, E. J. M. & Pidko, E. A. Highly efficient reversible hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to formates using a ruthenium PNP–pincer catalyst. ChemCatChem 6, 1526–1530 (2014).

Filonenko, G. A. et al. Lutidine-derived Ru–CNC hydrogenation pincer catalysts with versatile coordination properties. ACS Catal. 4, 2667–2671 (2014).

Zanatta, M. et al. Organocatalytic imidazolium ionic liquids H/D exchange catalysts. J. Org. Chem. 82, 2622–2629 (2017).

Anderson, P. A. et al. Designed synthesis of mononuclear tris(heteroleptic) ruthenium complexes containing bidentate polypyridyl ligands. Inorg. Chem. 34, 6145–6157 (1995).

Loch, J. A. et al. Palladium complexes with tridentate pincer bis-carbene ligands as efficient catalysts for C−C coupling. Organometallics 21, 700–706 (2002).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Nottingham for funding. V.S. gratefully acknowledges the Generalitat Valenciana (CIDEGENT/2018/036) for funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.W. and V.S. envisioned the worked, develop the relevant hypotheses, and designed the experiments. A.W. did all the experimental work. S.P.A. resolved and interpreted the crystal structure. A.W. and V.S. analysed and interpreted the data and co-wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Tiancheng Mu, Kuo-Wei Huang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weilhard, A., Argent, S.P. & Sans, V. Efficient carbon dioxide hydrogenation to formic acid with buffering ionic liquids. Nat Commun 12, 231 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20291-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20291-0

This article is cited by

-

Advances in CO2 circulation hydrogen carriers and catalytic processes

Sustainable Energy Research (2024)

-

Formic acid stability in different solvents by DFT calculations

Journal of Molecular Modeling (2024)

-

Converting CO2 to formic acid by tuning quantum states in metal chalcogenide clusters

Communications Chemistry (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.