Abstract

Growth of the Andes has been attributed to Cenozoic subduction. Although climatic and tectonic processes have been proposed to be first-order mechanisms, their interaction and respective contributions remain largely unclear. Here, we apply three-dimensional, fully-dynamic subduction models to investigate the effect of trench-axial sediment transport and subduction on Andean growth, a mechanism that involves both climatic and tectonic processes. We find that the thickness of trench-fill sediments, a proxy of plate coupling (with less sediments causing stronger coupling), exerts an important influence on the pattern of crustal shortening along the Andes. The southward migrating Juan Fernandez Ridge acts as a barrier to the northward flowing trench sediments, thus expanding the zone of plate coupling southward through time. Consequently, the predicted history of Andean shortening is consistent with observations. Southward expanding crustal shortening matches the kinematic history of inferred compression. These results demonstrate the importance of climate-tectonic interaction on mountain building.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The magnitude of Cenozoic Andean crustal shortening varies significantly along the margin1,2,3. The largest shortening occurred within the middle of the convergent margin from around 10°S to 33°S and tapered out towards the north and south, fostering Andean growth since the Eocene4 (Fig. 1a). Various mechanisms have been proposed to account for observed Andean shortening, which generally falls into two categories, tectonic or climatic. Tectonic mechanisms highlight the effects of the subducting plate age5, slab dip angle6,7, the thickness and westward motion of the overriding plate5,8, slab–lower mantle interaction9, or slab-induced mantle flow10,11,12, while climatic mechanisms emphasize coupling along the plate interface due to sediment subduction13,14 or surface erosion15,16.

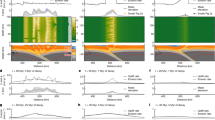

a Sediment thickness in oceans58 and the topography of the Andes. White thick arrows indicate plate velocities. Black thin arrows indicate trench velocities. b Reconstruction of the Juan Fernandez Ridge relative to South America22. Dashed lines represent the paleo-positions of JFR from 60 Ma to present with an interval of 10 Myrs. Thick semi-transparent lines represent ocean currents, with the cold Humboldt Current (or Peru Current) colored with blue and the rest with black. The green arrow indicates the transport direction of trench-fill sediments. c variation of the maximum Andean topography and the thickness of trench-fill sediments with latitude.

Several key observations related to Andean shortening have been noted earlier. First, the present-day trench segment from 12°S to 33.5°S is starved of sediments (Fig. 1c). Seismic reflection surveys have revealed a sediment thickness of ≤0.5 km within the central Andean trench, in contrast to thicknesses of 1–3 km in northern and southern Andes17,18. The present-day sediment thickness has a largely inverse correlation with Andean topography and the width of the orogen13 (Fig. 1c). It has been suggested that sediments could lubricate or weaken the plate interface13,14. Sediments in the subduction channel have low frictional resistance and could release fluids and elevate pore pressure, which reduces the mechanical strength along the plate boundary faults19. Additionally, the effective viscosity of sediments is 2–3 orders of magnitude lower than subducted mafic rocks20, and the blanketing of the oceanic basement by sediments could warm the subducted plate13, both reducing the viscous coupling between the two plates. Conversely, trench sediment depletion may increase the strength of plate coupling, which then enhances deformation within the upper plate (see discussions in Supplementary Information).

Second, the transition from sediment enrichment to sediment starvation along the trench is sharp and coincides with the location where the JFR intersects the coast of Chile at 33.5°S (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1). This suggests the thick sediments south of the ridge are dammed by the topographic relief of JFR18,21 (see discussions in Supplementary Information). The flat-lying trench sediments south of the ridge (Supplementary Fig. 1) suggest a mass redistribution of sediments within the trench17,18,21. In fact, a prominent trench axial channel has been observed continuously from 44°S to 31°S (Supplementary Fig. 1), interpreted as the pathway of turbidity currents inside the trench21. These observations suggest the sediments can travel thousands of kilometers within the trench17,21 from south to north, following the descending direction of the trench topography.

Third, plate kinematics in regional and global reconstructions consistently suggests a southward migrating JFR (Fig. 1b). Assuming a fixed Juan Fernandez hotspot, the JFR hotspot track can be reconstructed using a recent plate reconstruction22. The predicted JFR intersected the trench at southern Peru in the middle Eocene (50–40 Ma). Since then the ridge migrated southward relative to the South American plate towards the present location of 33.5°S until 12 Ma then it has been relatively stationary. Several recent plate models22,23,24,25,26 yield slightly different positions of JFR relative to South America (see the “Methods” section), but they all agree on the overall southward migration. This is consistent with independent evidence on tectonic deformation27 and magmatic arc migration28 within central Chile.

In this study, we propose trench-axial sediment transport and subduction is an important mechanism for central Andean shortening and build three-dimensional geodynamic models to test this hypothesis. Based on the geological constraints on the detailed history of Andean evolution29 and our model results that produce a similar pattern of Andean shortening, we put forward a model of Andean evolution where the Juan Fernandez Ridge (JFR) acts as a barrier to the northward-migrating trench sediments (Supplementary Fig. 1); the southward migration of JFR since the Eocene (Fig. 1b) creates a southward expanding segment of the sediment-starved trench with enhanced plate coupling and crustal shortening, causing the southward growth of the Andes. This migrating Andean shortening is consistent with the kinematic history of inferred crustal compression. The model results are also consistent with the observed long-strike variation in the magnitude of crustal shortening.

Results

Computation of central Andean shortening

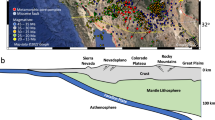

We build numerical models to investigate the role of sediment subduction and JFR migration on Andean shortening (see the “Methods” section, Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). The model starts with a realistic trench configuration of South America (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2), which we found to be important for upper plate deformation. Self-consistent free subduction is enabled during the computation, while the initial slab is generated by imposing surface plate motion22 from 60 to 45 Ma30 (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c). A lubricating layer with a low viscosity of 1019 Pa s is defined at the plate interface to decouple the two plates, mimicking the influence of sediments (Supplementary Fig. 3), with a thick (40 km) layer corresponding to weak coupling, and a thin (20 km) layer corresponding to strong coupling (see the “Methods” section). Here, we present three models for comparison with both their final subduction stages (Fig. 2) and the respective time evolution (Supplementary Figs. 4–6). The three models differ in the style of plate coupling, with Model 1 having uniformly weak coupling along the entire trench (Fig. 2d), Model 2 having a stationary strong coupling only in the central region (Fig. 2e), and Model 3 having a southward expanding region of strong coupling (Fig. 2f). The expansion of the strong coupling zone in Model 3 is realized by progressively shifting the southern edge (at a rate of 0.5°/Ma, Fig. 2f) of the lubricating layer towards the south to mimic the migration of JFR. Models are labeled in the time since starting with 34 Myr roughly corresponding to the present day.

a Model 1 where the lubricating layer has a uniform thickness (40 km) and the two plates are uncoupled along the trench. b Model 2 that has a plate coupling zone in the central Andes. The trench segment from 15°S to 35°S has a 20 km-thick lubricating layer, while the rest of the trench has a 40 km-thick lubricating layer. c Model 3 that has a southward expanding plate coupling zone, where the southern boundary of the plate coupling zone migrates towards the south with a rate of 0.5°/Myr. d–f Show the corresponding thickness of the lubricating layer in Model 1–3. h–j Show the cross-sections of the compositional fields at 22°S in Models 1–3. Compositional types 0–4 represent the ambient mantle, oceanic mantle lithosphere, oceanic crust, continental crust, and continental mantle lithosphere, respectively. Note crustal shortening in i and j. In a–c, the effective topography is shown on the South American Plate, which reflects crustal shortening shown in h–j, with reddish colors indicating stronger shortening than bluish colors. The second invariant of the stress tensor is shown on the oceanic plates. The coordinates in a–c are shown in radians.

In Model 1, the lubricating layer has a uniform effective thickness of 40 km along the trench (Supplementary Fig. 4). The negative buoyancy of the initial slab drives sustained subduction. We estimate the amount of Andean shortening by comparing the along-strike variation of trench retreat, with a smaller amount of retreat suggesting stronger shortening (see detailed discussion in the “Methods” section). After 32 Myr, most of the shortening occurs between 10°S and 20°S (Fig. 2a), straightening the originally curved trench (green dashed box in Supplementary Fig. 4). Quantitatively, the amount of shortening reaches a maximum value of 150 km between 10°S and 19°S and decreases to zero asymmetrically towards north and south. This shortening is inconsistent with inferences from balanced cross sections1,2 and paleomagnetism3 (Fig. 3a) where the amount of shortening reaches a maximum of around 20°S and decreases northward and southward symmetrically. This suggests other factors are controlling the observed pattern of Andean shortening. Additionally, we suggest that an initially curved trench tends to straighten if there are no other forces to balance the local sub-slab pressure gradient imposed by the curvature (Supplementary Fig. 7a).

a Comparison of relative trench retreat as modeled shortening (see the “Methods” section) with observed shortening along strike. b Comparison of the JFR migration with the onset of compression. The blue line and diamonds indicate the southward migration of trench–JFR intersection following plate reconstruction22. The blue shading represents the region (within 3° from the ridge axis) whose stress regime is directly affected by the collision of JFR with the continent, as revealed by the shoreline indentation of central Chile27. The orange diamonds indicate the onset of compressional structures in balanced cross sections32. The red and green lines show the timing of Nazca subduction re-initiation and when the slab enters the lower mantle based on seismic tomography33. The dark yellow rectangles represent proposed episodes of flat slabs inferred from magmatic distribution and tectonic evolution45,47, with the dashed area representing the uncertainties associated with the starting and end of the flat slab episodes. The gray, white, and orange rectangles show the compressional, neutral and extensional stress regimes of the Andes constrained by sedimentary records of the foreland and hinterland basins31,35,37.

Model 2 tests the role of enhanced plate coupling in the central Andes due to trench sediment starvation (Fig. 1), where we reduced the thickness of the lubricating layer to 20 km uniformly from 12°S to 33.5°S (Fig. 2e). As a result, the magnitude of the deviatoric stress (second invariant) in the central Andes is significantly increased (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 5), which causes stronger shortening in the upper plate and thickened crust and higher topography in the central Andes (Fig. 2b). The magnitude of shortening tapers out towards the north and south due to the waning of plate coupling, consistent with the trend of the observed shortening profile (Fig. 3a). However, shortening is over-predicted in the southern central Andes between 20°S to 32°S compared to observation (Fig. 3a). This suggests that enhanced plate coupling could be an important factor in causing the strong shortening in the central Andes, but there exist other mechanisms that reduce the coupling or shortening south of 20°S.

In Model 3, we apply a southward expanding plate coupling zone to mimic the role of the migrating JFR (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 6). The southern boundary of the plate coupling zone was initially at 18°S, which then gradually migrated to 33.5°S after 31 Myrs at a rate of 0.5°/Ma and remained stationary thereafter (Fig. 2f). Following the southward expansion of the plate coupling zone, the deviatoric stress along the plate interface increases towards the south (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 8). This causes a southward shortening and growth of the Andes (Supplementary Fig. 6). Finally, the predicted cumulative shortening reaches a maximum at 20.5°S, and decreases towards the north and south largely symmetrically, resembling that observed1,2,3 (Fig. 3a). This is the best-fit model that reproduces the concave margin and the high topography in the central Andes (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 9b), with a shortening profile largely consistent with that observed (Fig. 3a). Compared to Model 2, this one predicts less shortening south of 20°S by 50–150 km, due to a later onset of shortening associated with JFR migration. Note that after the passage of JFR, the segment would be experiencing continuous shortening until the present, as sediments remained depleted in the trench and the plate coupling remained strong. The decreasing duration of shortening toward the south provides one explanation for the less modified southern segment.

Geologically constrained Andean evolution

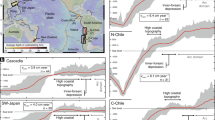

The Andes have experienced multiple stages of compression and extension31, but the major Andean shortening, where relatively large shortening rates led to the present-day high Andes, is believed to have occurred since the Eocene and is characterized by the activation of the Eocene and post-Eocene compressional structures9,32. We compare the migration of JFR to the onset of these compressional structures from balanced cross sections9,32,33, to illustrate the potential causal relationship (Fig. 3b). Observation shows that the major Andean shortening commenced in the middle Eocene around 15°S, and subsequently expanded southward, with the front of this expansion largely following the migrating JFR. For example, the individual onset of compressional structures along several transects at 20°S, 30°S, and 35°S all match the arrival of JFR (Figs. 3b, 4). The onset of compressional structures along 15°S at 45 Ma postdates the arrival of the JFR (Fig. 3b), but coincides with the Cenozoic cooling of climate34 (Supplementary Fig. 10a). This is likely because Cenozoic cooling is a necessary condition to reduce the trench sediments and increase plate coupling by initiating the arid climate in central Andes13. However, the transect at about 25°S has an onset age of 45 Ma predating the arrival of JFR at about 30 Ma (Fig. 3b), suggesting other mechanisms could have modified the Andes. On the other hand, foreland and hinterland sedimentary history31,35 suggest that the central Andes have been in compression since the Late Cretaceous (Fig. 3b). Between 26°S and 28°S, the broken foreland basins could have been partially activated at 55 Ma36. At about 30°S, some minor compression could have initiated before the late Eocene as inferred from the slow rate of basin subsidence37. We suggest these events could reflect earlier phases of compression before the major Andean shortening. Their corresponding mechanisms will be discussed later.

Compared to the onset of compression which could be complicated by a number of factors, the detailed kinematic history of Andean tectonic structures should provide better constraints on Andean evolution (Fig. 4). The demonstrated kinematic reconstruction is based on shortening estimates and timing constraints from 50 published balanced cross-sections (see the “Methods” section in ref. 29). We find the paleo-position of the JFR well correlates with these reconstructed motions of the compressional structures (Fig. 4). For example, within the central Andes, before the arrival of the JFR, the compressional structures are usually not activated or their motion is minor; while upon the arrival of the JFR, the compressional structures shift inboard with a fast convergence rate (about 0.5–3 cm/yr), suggesting strong deformation in the upper plate (Fig. 4a–e). The strong deformation persists long after the JFR has migrated southward away from the region. This observation supports the southward expanding plate coupling zone in the wake of JFR as a key driving mechanism for Andean shortening. We speculate that the collision of JFR with the overriding plate could have facilitated the subsequent long-term shortening by creating the first phase of structural damage to the overriding plate.

The kinematics of the Andean tectonic structures29 and the paleo-position of the JFR based on the reconstruction of Müller et al. 22 are shown for 40 Ma (a), 30 Ma (b), 20 Ma (c), 10 Ma (d) and present (e), respectively. The history of the sedimentary basins59 is shown, with extensional basins (blue stars) indicating crustal extension and foreland basins (pink stars) indicating compression. The orange dots represent the arc magmatism from R. Pilger’s compilation of Andean Igneous Isotopic Dates60. f the migration of the intersecting point between the trench and the JFR based on different plate reconstructions22,23,24,25,26. FHS fixed hotspot reference frame. HHS hybrid hotspot reference frame. SUB subduction reference frame.

Discussion

According to our model, the southward expansion of plate coupling is controlled by the along-strike variation of sediment influx, trench axial sediment transport, and the topographic barrier from the migrating JFR (Fig. 4a–e). Climate forces are critical in controlling sediment influx13,15. The present Andes is characterized by arid climate resulting from the subtropical atmospheric subsidence, the temperature inversion due to the cold Humboldt Current (Supplementary Fig. 11), and a rain-shadow of the high Andes associated with the westward trade wind38,39,40. These climate factors lead to reduced sediment supply to the trench from surface erosion and enhanced plate coupling that can cause strong deformation in the central Andes and supports the present-day high topography (Fig. 2). As proposed earlier13,15, the initiation of the arid climate system is likely due to the Cenozoic cooling34 (Supplementary Fig. 10a). This is consistent with the 45 Ma onset age of shortening in southern Peru which postdates the arrival of JFR (Fig. 3b) but coincides with the onset of cooling34.

Largely neglected in earlier studies is the effect of the climate forces in the southern Andes. Our model suggests the relatively rich sediment supply in the southern Andes plays an important role in controlling the pattern of plate coupling. These sediments feed to the trench south of JFR along the arid central Andes through trench axial channels17,18,21 (Fig. 4a–e) and decouple the two plates, which could result in a later onset and a reduced magnitude of shortening south of 20°S (Fig. 3a). The rich sediment supply is likely caused by high precipitation (Supplementary Fig. 11) due to the prevailing westerlies that carry the moisture from the Pacific41, enhanced tectonic erosion following tectonic uplift42, and a glacial “buzzsaw” effect at midlatitude41,43.

The relatively rich trench sediments in the southern Andes could also be associated with tectonic factors. Variation of plate convergence along the Andes22 (Supplementary Fig. 10b) could have influenced the consumption rate of trench sediments due to subduction. Before 30 Ma, the convergence rate in the southern Andes was less than half of that of the central Andes (Supplementary Fig. 10b). Therefore, a slower consumption rate of trench sediments was expected in the southern Andes, leading to the preservation of thick trench-fill sediments. We suggest a sediment thickness of ≥1 km is likely sufficient to decouple the two plates, as is the case for the Andes north of 10°S.

Tectonically, multiple mechanisms have been proposed to account for the central Andean shortening, including re-initiation of subduction33, changes in slab dip angle44,45, variation of overriding plate velocity31, changes in seafloor age5, and slab-lower mantle interaction9,10,12. Multiple geological events could be linked to these mechanisms. For example, the fast westward advance of South America has been proposed to account for the Late Cretaceous onset of compression for the central and southern Andes as revealed by sedimentary records in backarc basins31 (Fig. 3b). This compression significantly predated the major central Andean shortening. The early onset of compressional structures at 45 Ma along the transect at 25°S (Fig. 3b) could be attributed to slab-lower mantle interaction. Similarly, the Eocene compression at about 30°S inferred from basin subsidence37 (Fig. 3b) could also be explained by this mechanism. In addition, a recent study36 proposed this mechanism to be responsible for the formation of the broken foreland between 26°S and 28°S from 55 to 30 Ma. While we agree this mechanism could modify the Andean shortening, we speculate it only caused mild shortening and thus is not the main contributor for the major Andean shortening. This is because strong shortening was absent from the kinematic reconstruction of the compressional structures at these latitudes before and during the Eocene29 (Fig. 4). The inferred basin subsidence around 30°S has a slow rate in the Eocene compared to the later fast subsidence since the late Oligocene–early Miocene37 that was interpreted to be the onset of the most recent phase of major Andean shortening at this latitude46.

Of particular interest is the combination of two mechanisms, the slab-lower mantle interaction9, and the southward propagating subduction re-initiation33. In this scenario, the slab enters the lower mantle first in Peru and then propagates southward, causing the southward migration of shortening along the Andes (Fig. 3b). We challenge this hypothesis with two arguments. First, a nonuniform 10–30 Myrs time delay has been inferred along the Andes between the timing of slab penetration into lower mantle and the onset of compressional structures by reconstructing Nazca subduction using seismic tomography and constrains from magmatism33 (Fig. 3b). Second, according to this model, a larger amount of shortening is expected in the north than the south due to the longer duration of slab-lower mantle interaction—contradicting the observed northward tapering of shortening from northern Chile to northern Peru (Fig. 3a). We suggest southward expanding plate coupling due to sediment migration and subduction is a more likely mechanism, given the inverse correlation between sediment thickness and mountain height (Fig. 1c), the match between the strong-deformation front in the central Andes and the migration of JFR (Fig. 4), as well as the fit of the model that includes southward expanding plate coupling to the observed magnitude of shortening (Fig. 3a).

Flat slab subduction is another widely adopted mechanism for Andean shortening31,45,47. Multiple episodes of flat slabs have been proposed based on the magmatic distribution and tectonic structures of the Andes45 (Fig. 3b). These episodes of flat slabs have been proposed to be responsible for the formation of the broken forelands39,45 and the widening of the Andes47 (Fig. 3b). For example, in the Sierras Pampeanas, the thick-skinned deformation since the mid-Miocene coincides with the onset of Pampeanas flat slab, with the latter widely suggested as the cause of the former39,45,48. Therefore, a flat slab may be an important factor that contributes to the formation of the Andes. In fact, the flat slab and the model proposed by this study are not mutually exclusive. Subduction of the JFR has been proposed to be one mechanism for the formation of flat slab30,44, However, the proposed flat slabs in the central Andes from 15°S to 25°S do not continue to the present day (Fig. 3b). Therefore, the compressional force that maintains the long-term shortening is more likely related to enhanced plate coupling due to trench-sediment depletion. On the other hand, the broken foreland, as characterized by thick-skinned deformation, cannot be fully explained by flat slabs47 or the model proposed by this study, because some deformation was as early as 55 Ma36, predating flat-slab subduction and the arrival of JFR. This deformation has been proposed to be related to pre-existing structures in the basement39,49 and facilitated by tectonic compression that could be induced by slab–lower mantle interaction36. We suggest this deformation does not necessarily represent the start of the major Andean shortening. We emphasize the formation of the broken foreland represents extra complexities for the evolution of the Andes, since thick-skinned deformation may result in a reduced shortening rate compared to the preceding thin-skinned deformation, as is the case in the Sierras Pampeanas45. It may also be more difficult to measure the shortening for thick-skinned deformation due to the lack of stratigraphic markers. Therefore, it introduces extra uncertainty for the distinguishing of model 2 and model 3 using the amount of shortening. We will rely on future studies for a better understanding of these two deformation styles.

In summary, we define two phases of compression during central Andean evolution, with the first phase corresponding to the Paleocene–Eocene compression as recorded by sedimentary basin processes31,37,50, and the second phase to be the major central Andean shortening that initiated between Eocene and early Miocene depending on the latitude (Fig. 5). In contrast to the broad-scale major central Andean shortening that affected regions from the cordillera to the Subandean, the Paleocene–Eocene compression affected a much-focused area mostly in the Precordillera and the Western Cordillera31,51 (Fig. 5a), possibly with reactivation of some pre-existing structures in the foreland of the southern central Andes36. We suggest this earlier phase of compression that might be traced back to the Late Cretaceous31, is likely caused by the gradual shallowing of the slab with subduction duration52, rapid convergence between subducting and overriding plates31, or slab penetration9 and interaction with the lower mantle11,12. This compression caused low-magnitude crustal shortening (Fig. 5a), widely observed in compressive orogens. Note the southern Andes (south of 35°) experienced a synchronous neutral-to-extensional regime at that time (Fig. 3b). The compression that caused low-magnitude shortening53 was triggered later at about 20 Ma (Fig. 3b). This may be due to the higher sediment influx and lower sediment consumption in the southern Andes as discussed earlier, or because the southern Andes is more approximal to the edge of the subduction zone11, both of which tend to mitigate backarc compression.

a The first phase of compression is accompanied by mild shortening due to gradual shallowing of the slab with increasing subduction duration, slab–lower mantle interaction through the anchoring effect, and the rapid plate convergence. This occurred during Late Cretaceous to early Eocene when thick sediments were subducted. b The second phase of compression is accompanied by strong shortening due to enhanced plate coupling, which causes the main phase of Andean mountain building. This has been operating since Eocene following the arrival of JFR that deprived trench sediments in the north. The thick green line along the plate interface in a indicates trench-fill and subducted sediments. The red line along the plate interface in b indicates the sediment-depleted trench and subduction channel, suggesting a strong coupling between the two plates.

We suggest the latter phase of compression in the central Andes is mainly due to lack of sediment subduction. Since the Eocene, due to global cooling34 and the resulting arid climate in the central Andes, sediment supply to the trench was greatly reduced. This caused increased plate coupling and initiated the atypical extensive large-magnitude shortening that was accommodated by rapid retroarc underthrusting54 and deformation within the crust with variable strength55 (Fig. 5b). This compression, with flat slabs episodically modifying the Andes (Fig. 3b), could account for the main phase of Andean mountain building. We propose the plate coupling zone was first initiated in the north and then expanded towards the south, controlled by sediment influx and transport modulated by the southward migrating JFR. This explains the diachronous strong deformation since the middle Eocene as represented by the kinematics of the compressional structures (Fig. 4). We suggest trench-sediment transport and subduction are important processes that have a profound effect on the dynamics of plate boundaries and orogenesis. This model represents an example of cross-scale interaction in geology: a narrow “dam" to sediment transport in the trench could exert a strong influence on the formation of Andes.

Methods

Numerical model

We use the open-source finite-element code CitcomS56,57 for the computations. Assuming an incompressible mantle that satisfies the Boussinesq approximation, we solve for thermal–chemical convection governed by conservation of mass, momentum, and energy. The model setup and choice of parameter values are based on our earlier data-assimilation models30 that fit both upper mantle Benioff zone shapes and lower mantle structure from seismic tomography30. Some changes are made for this study, including a viscosity law with both diffusion and dislocation creep, a free-slip boundary condition at the top surface that allows for free subduction, and a higher Rayleigh number equal to 3.38 × 108 which corresponds to a mantle temperature of 1300 °C and a reference viscosity of 1021 Pa s (Supplementary Table 1).

To reiterate, a regional domain is used for all cases which cover the whole South America and the surrounding area from 30 to 120°W, 30°N–70°S, and radially from the core–mantle boundary to the surface. The model domain is discretized into 768 × 512 × 64 elements in longitude, latitude, and radius, respectively, with spatially variable mesh sizes and a resolution up to 10 km at the subduction zone.

The viscosity relation used is

where η is non-dimensional viscosity, T is temperature, r is the radius, A is the viscosity pre-factor, ηc is the intrinsic composition-dependent pre-factor, Ea is the activate energy with a non-dimensional value of 18, Toff is the temperature offset that has a value of 0.1 in the upper mantle and 0.6 in the lower mantle, \(\dot{{\epsilon }_{{\mathrm {II}}}}\) is the second invariant of the strain rate tensor, n is the stress exponent which equals 1.0 for diffusion creep and 3.5 for dislocation creep (Supplementary Table 2). The viscosity pre-factor for diffusion creep equals 0.25 in the upper mantle and transitions smoothly to 20 in the lower mantle. The dislocation creep has a viscosity pre-factor of 5 × 10−10, causing up to 1–2 orders of magnitude viscosity reduction in the upper mantle relative to the diffusion creep.

The final effective viscosity is controlled by the composite rheology of diffusion and dislocation creep and the pseudo-plasticity

where σy is the yield stress which equals 200 MPa throughout the mantle.

We use tracers (Lagrangian particles) to define the composition field. The geometry and properties of different compositions are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. A layered structure with uniform crust and lithosphere for both oceanic and continental plates is used. The continental lithosphere is further decomposed into the cratonic and non-cratonic regions. The shape of the craton is shown in Fig. 2, which resembles the present Amazonian Craton. Due to the limitation of the resolution, we set the thickness of the oceanic crust to be 25 km and the density to be 3200 kg/m3. The total buoyancy is equivalent to the typical oceanic crust of the Earth which has a density of 2900 kg/m3 and a thickness of 8 km. We set the initial continental crust to be 40 km thick with a density of 2800 kg/m3. The density of the continental mantle lithosphere is compositionally neutral with a thickness of 80 km for the non-cratonic region and 110 km for the cratonic region. This leads to a total thickness of 120 km for the non-cratonic lithosphere and 150 km for the cratonic lithosphere. The viscosity of the lithosphere is set to be 100 times the upper mantle pre-factor for the non-cratonic region and 2000 times the upper mantle pre-factor for the craton. A conductive thermal profile is initially set for the continent, of which the non-dimensional temperature decreases from 1.0 at the base of the continent to 0.0 at the surface. For the oceanic plate, we set the initial age to be 50 Myrs, and use half-space cooling to define the thermal structure.

For plate coupling, we define a lubricating layer at the plate interface (Supplementary Fig. 3), whose effect is similar to the subduction channel in earlier studies on plate coupling14 and to the weak zone in many other geodynamic models9,12. First, we monitored the composition of the elements vertically from the surface downward into the mantle. The first element that contains the tracers of the oceanic crust is defined as the element of the plate interface. By searching all elements near the subduction zone, a curved plate interface is constructed that conforms to the top surface of the slab. The non-dimensional viscosity within a certain distance of the plate interface is reduced to 0.01, to mimic the lubricating effect. Viscosity smoothing is applied to suppress large gradients. For a coupled case, the effective width of the lubricating layer is 20 km, while for a relatively uncoupled case, it is 40 km. These numbers are likely larger than the actual thickness of the subduction channel. They represent a compromise given the finite model resolution. By controlling the latitudinal ranges of the thin and thick lubricating layers, we test the pattern of plate deformation in response to the variation in plate coupling.

To generate the initial condition, we impose the surface plate motion from 60 to 45 Ma, which essentially generates several hundred kilometers of initial slabs at the subduction zone (Supplementary Fig. 2). Then we restart the model with a free-slip top boundary condition to initiate the free subduction. The model runs forward for 30–40 Myrs and the resultant plate deformation is compared to geological observations.

Estimating shortening

It is difficult to determine the absolute value of shortening in 3D geodynamic models because of the existence of subduction erosion at the leading edge of the overriding plate and distributed deformation within the plate. Following the method in ref. 11, we determine the relative shortening by comparing the variation of trench migration along strike. We first determine the trench location when the model starts by tracking the compositional boundary between oceanic and continental plates. Subsequently, we determine the trench location when the model ends using the same method. The two trench locations are compared to compute the lateral migration of individual points along the trench. We use the trench migration at 5°S as a reference. For any trench segment, a larger trench retreat than that at 5°S means extension, while a smaller trench retreat means shortening. Consequently, we are able to determine the shortening curves as presented in Fig. 3a.

This only provides the amount of shortening/extension in a relative sense. However, geological observations1,29,32 suggest a minor shortening at 5°S. This essentially puts the observed and geodynamically predicted shortening in the same reference frame so that they can be compared.

Reconstruction of JFR

The southward migration of JFR has been proposed by earlier studies27,28. With recent advances in plate reconstruction models, the path of JFR migration could be updated and more carefully examined. We assume a fixed Juan Fernandez hotspot at 79°W, 34°S, and use multiple plate reconstruction models22,23,24,25,26 to reconstruct the paleo-position of JFR. We first compute the present trajectory (partly subducted) of the JFR using the Euler poles of the Nazca Plate and the location of the Juan Fernandez hotspot. Then the whole trajectory is reconstructed backward in time by calculating the motion of the Nazca Plate relative to the South American plate. The intersection between the JFR and the pre-Andean trench3 is then computed at different ages, giving JFR migration curves in Fig. 4f.

We find all plate reconstructions produce a southward migrating JFR, suggesting it is a robust feature. Different models predict slightly different locations for the intersection point at particular ages. The difference is minor among the recent models after 2016 that have incorporated updates and revisions on the absolute reference frame22,24 and plate circuits25. We refer to these models to reconstruct the Andean evolution. Fig. 4a–e only shows the reconstructed JFR based on ref. 22, but we emphasize the other two models24,25 yield similar JFR migration.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper. The Source Data of the figures are provided as a supplementary file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The computational code CitcomS is available at the Computational Infrastructure for Geodynamics (CIG), https://geodynamics.org/. The python library PyGPlates that provides the functionality to reconstruct the paleo-tectonic features can be found at https://www.gplates.org/.

References

Kley, J. & Monaldi, C. R. Tectonic shortening and crustal thickness in the Central Andes: how good is the correlation? Geology 26, 723–726 (1998).

Oncken, O., Hindle, D., Kley, J., Elger, K., Victor, P. & Schemmann, K. Deformation of the central Andean upper plate system—facts, fiction, and constraints for plateau models. In The Andes (eds Oncken, O. et al.) 3–27 (Springer, 2006).

Arriagada, C., Roperch, P., Mpodozis, C. & Cobbold, P. R. Paleogene building of the Bolivian Orocline: tectonic restoration of the central Andes in 2-D map view. Tectonics 27, 1–14 (2008).

McQuarrie, N. Initial plate geometry, shortening variations, and evolution of the Bolivian orocline. Geology 30, 867–870 (2002).

Capitanio, F. A., Faccenna, C., Zlotnik, S. & Stegman, D. R. Subduction dynamics and the origin of Andean orogeny and the Bolivian orocline. Nature 480, 83–86 (2011).

Ramos, V. A. & Folguera, A. Andean flat-slab subduction through time. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 327, 31–54 (2009).

Martinod, J., Husson, L., Roperch, P., Guillaume, B. & Espurt, N. Horizontal subduction zones, convergence velocity and the building of the Andes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 299, 299–309 (2010).

Silver, P. G., Russo, R. M. & Lithgow-bertelloni, C. Coupling of South American and African plate motion and plate deformation. Science 279, 60–63 (1998).

Faccenna, C., Oncken, O., Holt, A. F. & Becker, T. W. Initiation of the Andean orogeny by lower mantle subduction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 463, 189–201 (2017).

Schellart, W. P., Freeman, J., Stegman, D. R., Moresi, L. & May, D. Evolution and diversity of subduction zones controlled by slab width. Nature 446, 308–311 (2007).

Schellart, W. P. Andean mountain building and magmatic arc migration driven by subduction-induced whole mantle flow. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–13 (2017).

Yang, T. et al. Contrasted East Asia and South America tectonics driven by deep mantle flow. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 517, 106–116 (2019).

Lamb, S. & Davis, P. Cenozoic climate change as a possible cause for the rise of the Andes. Nature 425, 792–797 (2003).

Sobolev, S. V. & Babeyko, A. Y. What drives orogeny in the Andes? Geology 33, 617–620 (2005).

Armijo, R., Lacassin, R., Coudurier-Curveur, A. & Carrizo, D. Coupled tectonic evolution of Andean orogeny and global climate. Earth-Sci. Rev. 143, 1–35 (2015).

Garcia-castellanos, D. The role of climate during high plateau formation . Insights from numerical experiments. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 257, 372–390 (2007).

Von Huene, R. et al. Tectonic control of the subducting Juan Fernández Ridge on the Andean margin near Valparaiso, Chile. Tectonics 16, 474–488 (1997).

Hoffmann-Rothe, A. et al. Oblique convergence along the chilean margin: partitioning, margin-parallel faulting and force interaction at the plate interface. In The Andes (eds Oncken, O. et al.) 125–146 (Springer, 2006).

Kopf, A. & Brown, K. M. Friction experiments on saturated sediments and their implications for the stress state of the Nankai and Barbados subduction thrusts. Mar. Geol. 202, 193–210 (2003).

Behr, W. M. & Becker, T. W. Sediment control on subduction plate speeds. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 502, 166–173 (2018).

Völker, D., Geersen, J., Contreras-Reyes, E. & Reichert, C. Sedimentary fill of the Chile Trench (32–46∘S): volumetric distribution and causal factors. J. Geol. Soc. 170, 723–736 (2013).

Müller, R. D. et al. Ocean Basin evolution and global-scale plate reorganization events since Pangea breakup. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 44, 107–138 (2016).

Seton, M. et al. Global continental and ocean basin reconstructions since 200 Ma. Earth-Sci. Rev. 113, 212–270 (2012).

Matthews, K. J. et al. Global plate boundary evolution and kinematics since the late Paleozoic. Glob. Planet. Change 146, 226–250 (2016).

Torsvik, T. H. et al. Pacific—Panthalassic reconstructions: overview, errata and the way forward. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 20, 3659–3689 (2019).

Shephard, G. E. et al. Testing absolute plate reference frames and the implications for the generation of geodynamic mantle heterogeneity structure. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 317-318, 204–217 (2012).

Yáñez, G., Cembrano, J., Pardo, M., Ranero, C. & Selles, D. The Challenger–Juan Fernández–Maipo major tectonic transition of the Nazca–Andean subduction system at 33–34 s: geodynamic evidence and implications. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 15, 23–38 (2002).

Kay, S. M. & Mpodozis, C. Magmatism as a probe to the neogene shallowing of the Nazca plate beneath the modern Chilean flat-slab. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 15, 39–57 (2002).

Schepers, G. et al. South-American plate advance and forced Andean trench retreat as drivers for transient flat subduction episodes. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–9 (2017).

Hu, J., Liu, L., Hermosillo, A. & Zhou, Q. Simulation of late Cenozoic South American flat-slab subduction using geodynamic models with data assimilation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 438, 1–13 (2016).

Horton, B. K. Tectonic Regimes of the Central and Southern Andes: responses to variations in plate coupling during subduction. Tectonics 37, 402–429 (2018).

Oncken, O., Boutelier, D., Dresen, G. & Schemmann, K. Strain accumulation controls failure of a plate boundary zone: linking deformation of the Central Andes and lithosphere mechanics. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 13, 1–22 (2012).

Chen, Y. W., Wu, J. & Suppe, J. Southward propagation of Nazca subduction along the Andes. Nature 565, 441–447 (2019).

Zachos, J., Pagani, M., Sloan, L., Thomas, E. & Billups, K. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science 292, 686–694 (2001).

Horton, B. K. Sedimentary record of Andean mountain building. Earth-Sci. Rev. 178, 279–309 (2018).

Zapata, S., Sobel, E., Del Papa, C. & Glodny, J. Upper plate controls on the formation of broken foreland basins in the Andean retroarc between 26 s and 28 s: from Cretaceous rifting to Paleogene and Miocene broken foreland basins. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 21, e2019GC008876 (2020).

Fosdick, J., Reat, E., Carrapa, B., Ortiz, G. & Alvarado, P. M. Retroarc basin reorganization and aridification during Paleogene uplift of the Southern Central Andes. Tectonics 36, 493–514 (2017).

Hartley, A. Andean uplift and climate change. J. Geol. Soc. 160, 7–10 (2003).

Stevens Goddard, A. L., Larrovere, M. A., Carrapa, B., Aciar, R. H. & Alvarado, P. Reconstructing the thermal and exhumation history of the Sierras Pampeanas through low-temperature thermochronology: a case study from the Sierra de Velasco. Bulletin 130, 1842–1858 (2018).

Ritter, B. et al. Neogene fluvial landscape evolution in the hyperarid core of the Atacama Desert. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–16 (2018).

Herman, F. & Brandon, M. Mid-latitude glacial erosion hotspot related to equatorial shifts in southern Westerlies. Geology 43, 987–990 (2015).

Thomson, S. N., Hervé, F. & Stöckhert, B. Mesozoic–Cenozoic denudation history of the Patagonian Andes (Southern Chile) and its correlation to different subduction processes. Tectonics 20, 693–711 (2001).

Thomson, S. N., Brandon, M. T., Tomkin, J. H., Reiners, P. W. & Wilson, N. J. Glaciation as a destructive and constructive control on mountain building. Nature 467, 313–317 (2010).

Gutscher, M.-A., Spakman, W., Bijwaard, H. & Engdahl, E. R. Geodynamics of flat subduction: seismicity and tomographic constraints from the Andean margin. Tectonics 19, 814–833 (2000).

Ramos, V. A. Anatomy and global context of the Andes: Main geologic features and the Andean orogenic cycle. In Backbone of the Americas: Shallow Subduction, Plateau Uplift, and Ridge and Terrane Collision, (eds Kay, S. M., Ramos, V. A., & Dickinson, W. R.) Vol. 204, 31–65 (Geological Society of America, 2009).

Jordan, T., Schlunegger, F. & Cardozo, N. Unsteady and spatially variable evolution of the Neogene Andean Bermejo Foreland Basin, Argentina. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 14, 775–798 (2001).

Martinod, J., Gérault, M., Husson, L. & Regard, V. Widening of the Andes: an interplay between subduction dynamics and crustal wedge tectonics. Earth-Sci. Rev. 204, 103170 (2020).

Jordan, T. E. & Allmendinger, R. W. The Sierras Pampeanas of Argentina; a modern analogue of rocky mountain foreland deformation. Am. J. Sci. 286, 737–764 (1986).

Payrola, P. et al. Episodic out-of-sequence deformation promoted by Cenozoic fault reactivation in NW Argentina. Tectonophysics 776, 228276 (2020).

DeCelles, P. G., Carrapa, B., Horton, B. & Gehrels, G. E. Cenozoic foreland basin system in the Central Andes of Northwestern Argentina: implications for Andean geodynamics and modes of deformation. Tectonics. 30 (2011).

DeCelles, P. et al. Cyclical orogenic processes in the Cenozoic central Andes. Geol. Soc. Am. Mem. 1212, 459–490 (2015).

Hu, J. & Gurnis, M. Subduction duration and slab dip. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 21, e2019GC008862 (2020).

Vietor, T. & Echtler, H. Episodic neogene southward growth of the Andean subduction Orogen between 30∘S and 40∘S—plate motions, Mmantle flow, climate, and upper-plate structure. In The Andes (eds Oncken, O. et al.) 375–400 (Springer, 2006).

Decelles, P. G., Ducea, M. N., Kapp, P. & Zandt, G. Cyclicity in Cordilleran orogenic systems. Nat. Geosci. 2, 251–257 (2009).

Ibarra, F. et al. 3d data-derived lithospheric structure of the central andes and its implications for deformation: insights from gravity and geodynamic modelling. Tectonophysics 766, 453–468 (2019).

Tan, E., Choi, E., Thoutireddy, P., Gurnis, M. & Aivazis, M. GeoFramework: coupling multiple models of mantle convection within a computational framework. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 7, 1–14 (2006).

Zhong, S., McNamara, A., Tan, E., Moresi, L. & Gurnis, M. A benchmark study on mantle convection in a 3-D spherical shell using CitcomS. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 9, 1–32 (2008).

Whittaker, J. M., Goncharov, A., Williams, S. E., Müller, R. D. & Leitchenkov, G. Global sediment thickness data set updated for the Australian-Antarctic Southern Ocean. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 14, 3297–3305 (2013).

Horton, B. K. & Fuentes, F. Sedimentary record of plate coupling and decoupling during growth of the Andes. Geology 44, 647–650 (2016).

Pilger, R. Andean Igneous Isotopic Dates http://www.pilger.us/id3.html (2011).

Acknowledgements

We used the open-source software PyGPlates to reconstruct the paleo-structures. L.L. and J.H. were supported by the National Science Foundation through EAR-1565640 and EAR-1554554. M.G. and J.H. were supported by the National Science Foundation through EAR-1645775. J.H. was also partially supported by the National Science Foundation of China through project 42174106. Computations were carried out on the NSF-supported Frontera supercomputers at the Texas Advanced Computer Center and were also supported by Center for Computational Science and Engineering of Southern University of Science and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H. conceived the study and performed the numerical experiments. L.L. and M.G. provided valuable advices throughout the study. All the authors participated in manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer Review Information Nature Communications thanks Sebastian Zapata for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, J., Liu, L. & Gurnis, M. Southward expanding plate coupling due to variation in sediment subduction as a cause of Andean growth. Nat Commun 12, 7271 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27518-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27518-8

This article is cited by

-

Deconstructing plate tectonic reconstructions

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2023)

-

Secular craton evolution due to cyclic deformation of underlying dense mantle lithosphere

Nature Geoscience (2023)

-

Paleogene India-Eurasia collision constrained by observed plate rotation

Nature Communications (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.