Abstract

While studies suggest that light and feeding patterns can reset circadian rhythms in various metabolites, whether these shifts follow a predictable pattern is unknown. We describe the first phase response curves (PRC) for lipids and hepatic proteins in response to combined light and food stimuli. The timing of plasma rhythms was assessed by constant routine before and after exposure to a combined 6.5-hour blue light exposure and standard meal schedule, which was systematically varied by ~20° between individuals. We find that the rhythms shift according to a PRC, with generally greater shifts for lipids and liver proteins than for melatonin. PRC timing varies relative to the stimulus, with albumin and triglyceride PRCs peaking at a time similar to melatonin whereas the cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein PRCs are offset by ~12 h. These data have important implications for treating circadian misalignment in shiftworkers who consume meals and are exposed to light around the clock.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While studies suggest that light and feeding patterns can reset circadian rhythms in various metabolites, whether these shifts follow a predictable pattern is unknown. Here, we describe the first phase response curves (PRC) for lipids and hepatic proteins in response to combined light and food stimuli. The timing of plasma rhythms was assessed by constant routine (CR) before and after exposure to a combined 6.5-h blue light exposure and standard meal schedule, which was systematically varied by ~20° between individuals. The rhythms shifted according to a PRC, with generally greater shifts for lipids and liver proteins than for melatonin. PRC timing varied relative to the stimulus, with albumin and triglyceride PRCs peaking at a time similar to melatonin whereas the cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein PRCs were offset by ~12 h. These data have important implications for treating circadian misalignment in shiftworkers who consume meals and are exposed to light around the clock.

Circadian rhythms in physiology, metabolism and behaviour are driven by a multioscillatory system, in which the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is the retinorecipient central circadian pacemaker critical for synchronising circadian rhythms to daily light–dark cycles. Under controlled conditions, the daily rhythms of core-body temperature, and of melatonin and cortisol secretion are considered robust markers of the timing of the central circadian pacemaker1. In addition, there are circadian clocks located in peripheral organs and tissues that are thought to refine the timing of local physiological systems in concert with the central pacemaker and are reset by both photic and non-photic time cues in animal models2. To date, there is limited evidence for endogenous peripheral clocks in humans. While significant day-night3,4,5,6 and endogenous circadian rhythms6,7,8,9,10,11 in a range of metabolites have been documented, it is unknown whether these metabolic rhythms are controlled by peripheral clocks, the central pacemaker, or both.

Light is considered the most powerful time-cue (zeitgeber) for resetting the central circadian pacemaker in humans, as assessed using markers such as melatonin, cortisol, and core-body temperature12. Non-photic time cues such as exercise or mealtimes can also reset circadian rhythms of these markers in humans, but are much weaker stimuli than light10,13,14,15,16,17. Interestingly, in rodents, peripheral clocks can shift independently from the light schedule, uncoupling from the SCN and aligning with mealtime under time-restricted feeding schedules18,19. Whether such uncoupling occurs in humans is not well characterised20. Recent evidence suggests that timed meals play a role in synchronising plasma glucose rhythms and core clock gene expression in adipose tissue15 and that metabolite rhythms can be shifted out of alignment with central circadian markers by behavioural time cues (e.g., sleep/wake and feeding/fasting cycles)10.

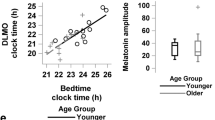

The direction and magnitude of circadian phase resetting in response to a stimulus are described by a PRC. The degree of phase shift in response to light is affected by the timing, intensity, duration, and wavelength of the light stimulus. Previously, we described the PRC for shifts in the centrally controlled melatonin rhythm to either 6.7 h or 1 h of white light21,22,23, and the respective dim light controls23, thereby isolating the effects of light from meal timing, which was identical between conditions. More recently, we constructed a PRC to a 6.5 h blue (480 nm) light stimulus [the peak sensitivity of the melanopsin-containing intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) that primarily mediate photic circadian resetting24], using the same protocol25, and found maximal phase resetting to be similar, at ~3 h.

In the present analysis of the same blue light study, we investigated the phase-resetting effects of the stimulus on peripheral rhythms in circulating lipids and clinical markers of hepatic function. As in the white light PRC studies, the stimulus was a combination of the 6.5-h light pulse and a standard meal schedule (three meals and a snack). Sixteen healthy participants (18–30 years; 8F) were studied for 9–10 days in an environment free of time cues. Endogenous circadian rhythms in these markers were assessed under CR conditions, which included constant wake in dim light, continuous semi-recumbent posture, and identical isocaloric snacks and fluids every hour. This protocol removes or evenly distributes environmental stimuli, such as sleep-wake, rest-activity, and feeding-fasting cycles, that may potentially mask the endogenous circadian rhythm26.

Following three inpatient baseline days (8:16 h sleep:wake), participants underwent a 30- to 52-h CR (CR1) to assess initial circadian phase, the combined light exposure (LE)/mealtime day preceded and followed by an 8-h sleep episode, and then a second 32- to 55-h CR (CR2) to assess any resultant shifts in circadian rhythms (Fig. 1). The 16-h combined light/meals exposure day was identical between individuals except that the timing was systematically varied to schedule the midpoint of the day 80 min (~20°) apart between participants to collectively cover all circadian phases. Breakfast, lunch, dinner, and a snack were served at 2.67, 4.42, 12.42, and 14.42 h after waking, respectively—an 11.75-h feeding window—and the 6.5-h 480 nm LE was scheduled from 4.75 to 11.25 h after waking.

The schedule for participants (A) 29K6V and (B) 29R8V, plotted in raster format. White and grey bars indicate wake episodes in ambient light of <190 lux or <3 lux, respectively. Black bars indicate scheduled sleep in darkness (0 lux). The hatched bars indicate the 6.5-h light exposure (LE). The open circles indicate the timing of meals and snacks (smaller circle) during the exposure day.

Results

Circadian rhythm assessment

First, data from CR1 and CR2 were fit separately with 24-h sinusoidal functions to establish endogenous circadian rhythmicity and determine the peak time (acrophase) of the rhythms (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1)27. Phase shifts were calculated for each participant for each parameter individually as the change in acrophase clock time between CR1 and CR2. Only significant sinusoidal fits (amplitude different from zero, two-tailed, p < 0.1) were used to estimate acrophase and calculate phase shifts. During CR1, among the 16 participants studied, significant 24-h rhythms were detected in total protein (n = 11), albumin (n = 7), globulin (n = 9), total cholesterol (n = 9), triglycerides (n = 13), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) (n = 9), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) (n = 9) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 2). During CR2, significant 24-h rhythms were detected during CR2 in total protein (n = 14), albumin (n = 12), globulin (n = 11), total cholesterol (n = 8), triglycerides (n = 16), LDL-C (n = 13), and HDL-C (n = 14).

Data collected during CR1 (black filled circles) and CR2 (grey open circles) for (A, E) albumin, (B, F) total cholesterol, (C, G) triglycerides, and (D, H) HDL-C. The x-axis is the time each blood sample was taken and the y-axis is the clinical assay concentration. The solid black line is the fitted cosinor regression for CR1 and the grey solid line is the fitted cosinor regression for CR2. The phase shift (Δϕ) and participant ID for each example is noted in the bottom right corner of the plots. The exposure day schedule is represented in the bar above the plots; grey bars indicate wake episodes in ambient light <3 lux, hatched bars indicate the 6.5-h light exposure (LE), and the open circles indicate the timing of meals and snacks.

Constructing phase response curves

Next, to construct the PRCs, the timing of the stimulus (defined as the timing of LE onset during the exposure day) was expressed relative to the acrophase of each parameter during CR1 (abscissa) and plotted against the phase shift observed (ordinate) for phase advances (shifting earlier, positive value) or phase delays (shifting later, negative value) per convention (Fig. 3). There were statistically significant PRCs for melatonin (inter-individual range of shifts −2.59 to 1.52-h, nonlinear regression overall fit p = 0.0001), albumin (−5.05 to 7.12-h, p = 0.016), total cholesterol (−2.32 to 7.15-h, p = 0.0013), triglycerides (−8.32 to 2.11-h, p = 0.0004), and HDL-C (−3.73 to 4.60-h, p = 0.042). Shifts in total protein, globulin, and LDL-C did not exhibit a PRC (p > 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 3).

Raw phase shifts in (A) melatonin, (B) albumin, (C) total cholesterol, (D) triglycerides, and (E) HDL-C plotted as a function of circadian phase of the stimulus, defined as the onset of LE - CR1 assay-specific acrophase. PRCs are double-plotted. The solid horizontal black line indicates no phase shift. Black squares represent each individual that had statistically significant cosinor regressions in the assay during both CR1 and CR2. The solid sinusoidal black line is the fitted single-harmonic function. The 95% confidence intervals generated from the fit single-harmonic function are shown by the grey dotted lines.

To assess whether the variance in the resetting response was better explained when modelled relative to the phase of the central pacemaker (rather than relative to the phase of each respective parameter separately), PRCs were also constructed defining circadian phase of the stimulus relative to the melatonin rhythm, assessed by the timing of dim light melatonin onset (DLMO), a reliable marker of the central pacemaker. Constructing PRCs relative to DLMO also allowed direct comparison to the PRC for shifts in melatonin25. This approach did not improve the PRC fits in general: The r2 was higher when PRCs were constructed using the initial circadian phase of the stimulus to determine exposure timing for melatonin (0.80 vs. 0.76), albumin (0.60 vs. 0.07), total cholesterol (0.70 vs. 0.25), and triglycerides (0.50 vs. 0.50), but not HDL-C (0.39 vs. 0.61) (Supplementary Table 2). To assess coupling of the central and putative peripheral rhythms, phase shifts of melatonin were compared to the phase shifts in the lipid and hepatic markers. There were no statistically significant correlations between phase shifts of melatonin and the phase shifts of the other parameters (p > 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 4). There were also no significant changes in parameter amplitude between the two CRs when using z-scored data for albumin, total cholesterol, or HDL-C, but there was a lower amplitude during CR2 for triglycerides (paired t-test, p = 0.02) (Supplementary Fig. 5). The degree of phase shift was not associated with changes in amplitude for any of the markers (p > 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 5).

Phase response curves adjusted to relative clock time

Finally, to enable a direct comparison of PRC timings, the PRCs were re-plotted on the same scale, using the clock time of the group average CR1 acrophase as ‘0’ for the timing of the stimulus (i.e., 0 representing when light onset is coincident with the acrophase for the group during CR1, and realigned along the x-axis to the corresponding clock time) (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Discussion

While the robust entraining effects of light on the central circadian pacemaker have been clearly established, little is known about the effects of photic and non-photic stimuli on the regulation of circadian rhythms of peripheral metabolic markers in humans. In this study, we evaluated the effects of a combined photic and non-photic stimulus on clinical plasma markers of hepatic function and lipids, specifically total protein, albumin, globulin, total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL-C, and HDL-C. Similar to melatonin, phase resetting of albumin, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and HDL-C followed a type 1 PRC25, but the magnitude and direction of shifts differed from melatonin, suggesting different control and phase-resetting properties than markers of the central circadian pacemaker.

The metabolic rhythms were less consistently rhythmic than melatonin, although a majority of individuals exhibited significant rhythms in total protein, globulin, total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL-C, and HDL-C when analysed using the typical cosinor model. The CR protocol is the gold standard technique for defining internally generated circadian rhythms and their presence provides definitive evidence for endogenous rhythms in these clinical markers. This finding has important clinical implications as this natural circadian variation is not taken into account when assessing laboratory test results, which may confound clinical decisions that are often based on normative data derived from a single time point28.

The current protocol cannot conclusively determine whether these rhythms are under the control of the central and/or peripheral clock(s), or whether light or meal timing is the principal resetting signal. The observation that liver function and lipid rhythms do not shift in parallel with the centrally controlled melatonin rhythm, and exhibit larger phase shifts, suggests that they may be separately regulated. Other centrally controlled markers, such as core-body temperature and cortisol, have the same endogenous period and a stable phase relationship with melatonin29,30, and shift in parallel with melatonin in response to light21,31,32. These findings suggest that these peripheral rhythms are not just more ‘hands’ of the central clock but represent separately generated and regulated peripheral rhythms, as confirmed in in vivo and in vitro studies in animal models, including in the liver19,33,34. We postulate that the same is true in humans.

While in rodents there is compelling evidence that peripheral tissues can generate endogenous rhythmicity independent from the SCN in vitro and in vivo35,36, in humans there is limited evidence for peripheral clock rhythms functioning independently and being shifted in a different direction, and to a different degree, than central clock markers (e.g., melatonin). The current data suggest such a functional separation, which we hypothesise is driven independent of the SCN by peripheral clocks. There is some evidence from animal studies that PRCs differ in response to photic and non-photic stimuli37 and that peripheral clocks can be reset according to a PRC38. Conversely, it may also be possible that differences in PRCs could result from the interaction between the SCN clock and other damped oscillators, or even uncoupling within the SCN clock itself.

Notwithstanding the source of the rhythmicity, the construction of type 1 PRCs from changes in phase between two CRs is clear evidence that these rhythms are under circadian control, and that they meet two canonical properties of a circadian rhythm: (i) are rhythmic in the absence of external time cues (demonstrated by CR1); and (ii) can be reset in response to a stimulus in a predictable manner (demonstrated by the PRCs). Furthermore, the magnitude of the Type 1 phase shifts in liver function and lipid profile markers are much greater, up to 8 h, compared to the ~3 h typically observed for central markers in response to light22,25,39.

Understanding the relative timing of the PRCs is complex given the large differences in the acrophase times between the parameters and the multifaceted stimulus (light and meal timing). Comparing the approximate clock time of the ‘0’ circadian phase exposure (where light onset is coincident with the parameter acrophase for the group during CR1), shows that the melatonin and triglyceride PRCs have similar timing (delay shifts in the ~12 h before their early morning acrophase) whereas total cholesterol and HDL-C profiles different by ~12 h (delay shifts in the 12 h before their late afternoon acrophase). Future studies that isolate the effects of either lighting or mealtimes are needed to determine which time cues each parameter is most sensitive.

To summarise, plasma markers of hepatic function and lipids show endogenous circadian rhythms that shift in response to a combined light and meal schedule. The direction and magnitude of the shifts in albumin, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and HDL-C can be described by conventional type 1 PRCs that are distinct from the PRC for melatonin. Further work is needed to demonstrate whether food or light is the main environmental time-cue resetting each peripheral marker. Understanding the temporal dynamics of peripheral circadian rhythms is critically important for designing behavioural and clinical approaches using photic and non-photic interventions to treat the circadian misalignment associated with shiftwork, jetlag, and disease40.

Methods

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital through the Partners Human Research Committee, in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave written informed consent prior to enroling in the study and were paid for their participation.

Participants

Twenty-one participants (10F, mean age ± SD: 23.10 ± 3.43 years) were studied for 9–10 days in the Intensive Monitoring Unit (IPM) of the Center for Clinical Investigation (CCI) at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA between May and December 2009.

Experimental protocol

During the 9–10 day protocol, participants remained in an individual time-free suite. The protocol started with three baseline days consisting of 8 h of scheduled sleep in darkness (<0.02 lux, <0.00006 W/m2) and 16 h of scheduled wake in ambient light. Ambient light was provided by 4100 K fluorescent lamps (Philips Lighting, The Netherlands) with digital ballasts (Lutron Electronics Co., Inc, PA) transmitted through a UV-stable filter (Lexan 9030 with prismatic lens, GE Plastics, MA) and light levels were ~90 lux [0.23 W/m2 (~89 lux) at 137 cm in the vertical plane and 0.48 W/m2 (~190 lux) in the horizontal plane at a height of 187 cm]. Halfway through Day 3, the light intensity was dimmed to ~0.5 lux (0.001 W/m2) at 137 cm from the floor in the vertical plane with a maximum <3 lux (0.01 W/m2) at 187 cm from the floor in the horizontal plane anywhere in the room for the remainder of the study. Participants were in darkness during scheduled sleep. At wake time on Day 4, participants began an initial ~30–52-h CR in <3 lux during which time participants remained awake in a semi-recumbent position in bed and were provided equal isocaloric snacks at hourly intervals while being constantly monitored by a technician to maintain wakefulness. Following an 8-h sleep episode, participants were exposed to the photic stimulus, which was monochromatic 480-nm light (11.8 μW/cm2; 2.8 × 1013 photons/cm2/s; ≤15-nm half peak bandwidth) for 6.5 h via a modified Ganzfeld dome25 centred in the 16-h wake episode, and the non-photic stimulus, which included meals at 2.67 h (mean % of daily calories = 27%), 4.42 h (28%), 12.42 h (31%), and 14.42 h (13%) after waking. Following another 8-h sleep episode, participants started a second CR (~32–55 h), followed by a 10-h recovery sleep episode before discharge.

Blood sampling

Starting on Day 2, an indwelling, intravenous catheter was inserted in each participant’s forearm vein and plasma samples were collected every 20–60 min. Plasma samples collected during CR1 and CR2 were previously assayed for melatonin25, and re-assayed by a CLIA certified laboratory blind to the conditions of the experiment for either a lipid panel (total cholesterol, HDL-C, LDL-C, triglycerides, CHOL/HDL-C ratio, non HDL-C; Test code: 7600, Quest Diagnostics, LLC Marlborough, MA) or hepatic protein panel (total protein, albumin, globulin, and albumin/globulin ratio) (Test code: 90843, Quest Diagnostics, LLC Marlborough, MA), every 1–2 h such that every other sample was assayed for the same panel. The assays measured directly were total protein, albumin, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and HDL-C. Globulin and LDL-C were calculated by Quest Diagnostics (LLC Marlborough, MA) using clinically accepted standards.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and graphical representations were produced using Prism 8.4 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla CA, USA). As reported in ref. 25, three participants were excluded for protocol compliance/errors and two additional participants were excluded because there was insufficient data to accurately assess the phase of melatonin. For the present study, we only analysed data from the 16 participants (8F, mean age ± SD 24.00 ± 3.16 years) who were included in the construction of the PRC for shifts in melatonin25.

There were a total of 1795 plasma samples assayed for lipids and hepatic proteins (7 of which could not be assayed). The 1795 samples were the same plasma samples previously analysed for melatonin (1 of which could not be assayed). In total, 27 samples (1.50%) were removed prior to analysis of phase shifts and PRC construction because of abnormal concentrations (e.g., out of the range of detection or values being outside of normative).

Circadian rhythm analysis

Rhythms were assessed using a cosinor regression of the form41:

where y is the assay result (i.e., concentration), x is the clock time of the sample, μ is the mesor, and ϕ is the acrophase. The cutoff used for statistical significance was p < 0.1 (two-tailed).

Phase response curve

Phase shifts were calculated as the difference between initial phase (CR1 acrophase) and final phase (CR2 acrophase) of the rhythms. Per convention, phase delays were plotted as negative values and phase advances as positive values on the ordinate.

The PRC was fitted with a single-harmonic function of the form:

where x is circadian phase and y is phase shift. Parameters μ, A, ϕ represent the mean phase shift, amplitude, and phase, respectively, and pseudo-r2 and 95% confidence intervals were computed from the resulting fitted function. Statistical significance was determined using the overall fit of the nonlinear regression (PROC NLIN). Additional methods are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The minimum dataset necessary to interpret, verify and extend the research in this article is available within the manuscript and its supplementary information. Source data are provided with this paper. De-identified individual data for all outcomes are provided in the Harvard Dataverse repository (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YADCK8)42.

Change history

20 April 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29917-x

References

Klerman, E. B., Gershengorn, H. B., Duffy, J. F. & Kronauer, R. E. Comparisons of the variability of three markers of the human circadian pacemaker. J. Biol. Rhythm 17, 181–193 (2002).

Brown, S. A. & Azzi, A. In Circadian Clocks. (eds Kramer, A. & Merrow, M.) 45–66 (Springer, 2013) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-25950-0.

Ang, J. E. et al. Identification of human plasma metabolites exhibiting time-of-day variation using an untargeted liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry metabolomic approach. Chronobiol. Int. 29, 868–881 (2012).

Davies, S. K. et al. Effect of sleep deprivation on the human metabolome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 10761–10766 (2014).

Gu, F. et al. Diurnal variation of metabolites in three individual participants. Chronobiol. Int. 36, 332–342 (2019).

Grant, L. K. et al. Endogenous circadian regulation and phase resetting of clinical metabolic biomarkers. J. Pineal. Res., e12752 (2021).

Kervezee, L., Cermakian, N. & Boivin, D. B. Individual metabolomic signatures of circadian misalignment during simulated night shifts in humans. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000303 (2019).

Kasukawa, T. et al. Human blood metabolite timetable indicates internal body time. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 15036–15041 (2012).

Chua, E. C. et al. Extensive diversity in circadian regulation of plasma lipids and evidence for different circadian metabolic phenotypes in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 14468–14473 (2013).

Skene, D. J. et al. Separation of circadian- and behavior-driven metabolite rhythms in humans provides a window on peripheral oscillators and metabolism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 7825–7830 (2018).

Grant, L. K. et al. Circadian and wake-dependent changes in human plasma polar metabolites during prolonged wakefulness: a preliminary analysis. Sci. Rep. 9, 4428 (2019).

Czeisler, C. A. & Gooley, J. J. Sleep and circadian rhythms in humans. In Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. Vol. 72, 579–597 (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2007).

Buxton, O. M., Lee, C. W., L’Hermite-Balériaux, M., Turek, F. W. & Van Cauter, E. Exercise elicits phase shifts and acute alterations of melatonin that vary with circadian phase. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 284, R714–R724 (2003).

Barger, L. K., Wright, K. P. Jr, Hughes, R. J. & Czeisler, C. A. Daily exercise facilitates phase delays of circadian melatonin rhythm in very dim light. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 286, R1077–R1084 (2004).

Wehrens, S. M. T. et al. Meal timing regulates the human circadian system. Curr. Biol. 27, 1768–1775 e1763 (2017).

Shea, S. A., Hilton, M. F., Orlova, C., Ayers, R. T. & Mantzoros, C. S. Independent circadian and sleep/wake regulation of adipokines and glucose in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 2537–2544 (2005).

Klerman, E. B. et al. Nonphotic entrainment of the human circadian pacemaker. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 274, R991–R996 (1998).

Damiola, F. et al. Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Dev. 14, 2950–2961 (2000).

Stokkan, K.-A., Yamazaki, S., Tei, H., Sakaki, Y. & Menaker, M. Entrainment of the circadian clock in the liver by feeding. Science 291, 490–493 (2001).

Lewis, P., Oster, H., Korf, H. W., Foster, R. G. & Erren, T. C. Food as a circadian time cue—evidence from human studies. Nat. Rev. Endocrin. 16, 213–223 (2020).

Czeisler, C. A. et al. Bright light induction of strong (type 0) resetting of the human circadian pacemaker. Science 244, 1328–1333 (1989).

Khalsa, S. B. S., Jewett, M. E., Cajochen, C. & Czeisler, C. A. A phase response curve to single bright light pulses in human subjects. J. Physiol. 549, 945–952 (2003).

St Hilaire, M. A. et al. Human phase response curve to a 1 h pulse of bright white light. J. Physiol. 590, 3035–3045 (2012).

Fisk, A. S. et al. Light and cognition: Roles for circadian rhythms, sleep, and arousal. Front. Neurol. 9, 56 (2018).

Rüger, M. et al. Human phase response curve to a single 6.5 h pulse of short-wavelength light. J. Physiol. 591, 353–363 (2013).

Duffy, J. F. & Dijk, D. J. Getting through to circadian oscillators: why use constant routines? J. Biol. Rhythms 17, 4–13 (2002).

Cornelissen, G. Cosinor-based rhythmometry. Theor. Biol. Med. Model 11, 16 (2014).

Greco, C. M. & Sassone-Corsi, P. Personalized medicine and circadian rhythms: Opportunities for modern society. J. Exp. Med. 217, e20200702 (2020).

Czeisler, C. A. et al. Stability, precision, and near-24-hour period of the human circadian pacemaker. Science 284, 2177–2181 (1999).

Skene, D., Lockley, S., James, K. & Arendt, J. Correlation between urinary cortisol and 6-sulphatoxymelatonin rhythms in field studies of blind subjects. Clin. Endocrinol. 50, 715–719 (1999).

Boivin, D. B. & Czeisler, C. A. Resetting of circadian melatonin and cortisol rhythms in humans by ordinary room light. Neuroreport 9, 779–782 (1998).

Shanahan, T. L. & Czeisler, C. A. Light exposure induces equivalent phase shifts of the endogenous circadian rhythms of circulating plasma melatonin and core body temperature in men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 73, 227–235 (1991).

Gnocchi, D., Pedrelli, M., Hurt-Camejo, E. & Parini, P. Lipids around the clock: focus on circadian rhythms and lipid metabolism. Biology 4, 104–132 (2015).

Mauvoisin, D. et al. Circadian clock-dependent and-independent rhythmic proteomes implement distinct diurnal functions in mouse liver. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 167–172 (2014).

Sinturel, F. et al. Circadian hepatocyte clocks keep synchrony in the absence of a master pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus or other extrahepatic clocks. Genes Dev. 35, 329–334 (2021).

Koronowski, K. B. et al. Defining the independence of the liver circadian clock. Cell 177, 1448–1462.e14 (2019).

Mendoza, J., Graff, C., Dardente, H., Pevet, P. & Challet, E. Feeding cues alter clock gene oscillations and photic responses in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of mice exposed to a light/dark cycle. J. Neuro. 25, 1514–1522 (2005).

Balsalobre, A. et al. Resetting of circadian time in peripheral tissues by glucocorticoid signaling. Science 289, 2344–2347 (2000).

Boivin, D. B., Duffy, J. F., Kronauer, R. E. & Czeisler, C. A. Dose-response relationships for resetting of human circadian clock by light. Nature 379, 540–542 (1996).

Longo, V. D. & Panda, S. Fasting, circadian rhythms, and time-restricted feeding in healthy lifespan. Cell Metab. 23, 1048–1059 (2016).

St Hilaire, M. A., Rahman, S. A., Gooley, J. J., Witt-Enderby, P. A. & Lockley, S. W. Relationship between melatonin and bone resorption rhythms in premenopausal women. J. Bone Min. Metab. 37, 60–71 (2019).

Lockley, S. W. Circadian lipid and hepatic protein rhythms shift with a phase response curve different than melatonin. Harvard Dataverse https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YADCK8 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank Elizabeth Lydon, research staff, and research participants at the Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH); the technical, dietary, nursing and medical staff at the Center for Clinical Investigation at BWH in partnership with the Harvard Catalyst; Jonathan Williams M.D., for medical supervision; Ralph Todesco (BWH), George C. Brainard Ph.D, John P. Hanifin Ph.D (Thomas Jefferson University), Ron Kovak and Jon Cooke (PTI, Inc.) for technical support for the generation of monochromatic light; George C. Brainard Ph.D (Thomas Jefferson University) for support in the design of the lighting interventions; and Vincent Ricchiuti, Ph.D. and the Core Laboratory staff (BWH) for melatonin assays. This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant 5R01MH45130 (C.A.C., S.W.L.). B.A.K. was supported by NIH-NINDS K99/R00 NS109909. S.A.R. and M.S.H. were supported by an NHLBI training grant T32-HL07901. S.A.R., M.S.H., L.K.G., C.A.C. and S.W.L. were supported by NASA NNX14AK53G, M.S.H. by NINR R21NR018974 and NASA 80NSSC20K0576, and C.A.C. by NIA P01 AG009975. S.A.R., M.R., C.A.C., and S.W.L. were supported, in part, by the National Space Biomedical Research Institute through NASA NCC 9–58. This work was also supported by the National Center for Research Resources through grants to Brigham and Women’s Hospital General Clinical Research Center (NCRR M01 RR02635) and the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NCRR UL1 RR025758).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to and approved this manuscript. C.A.C. and S.W.L designed the initial studies. S.A.R., M.R., C.A.C. and S.W.L. contributed to or oversaw data collection. B.A.K., S.A.R., M.S.H., L.K.G., C.A.C. and S.W.L. contributed to the analysis of the data. B.A.K. and S.W.L. drafted the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

B.A.K., L.K.G., and M.R. declare no competing interests. S.A.R. holds patents for Prevention of Circadian Rhythm Disruption by Using Optical Filters and Improving sleep performance in subject exposed to light at night; S.A.R. owns equity in Melcort Inc.; has provided paid consulting services to Sultan & Knight Limited, Bambu Vault LLC, Lucidity Lighting Inc.; and has received honoraria as an invited speaker and travel funds from Starry Skies Lake Superior, PennWell Corp., and Seoul Semiconductor Co. Ltd. These interests were reviewed and managed by Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Partners HealthCare in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. M.S.H. has provided paid limited consulting for The MathWorks, Inc. M.S.H. has received honoraria and travel funds as an invited speaker from the Providence Sleep Research Interest Group and the Mayo Clinic Metabolomics Resource Core. C.A.C. reports grants to B.W.H. from NHLBI, NIA, NIOSH, and DOD; is/was a paid consultant to Bose, Boston Celtics, Boston Red Sox, Cephalon, Institute of Digital Media and Child Development, Klarman Family Foundation, Jazz Pharma, Merck, Purdue Pharma, Samsung, Teva Pharma Australia, AARP, American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine, Eisenhower Medical Center, M. Davis and Company, Physician’s Seal, UC San Diego, University of Washington, University of Michigan, Maryland Sleep Society, National Sleep Foundation, Sleep Research Society, Tencent, and Vanda Pharmaceuticals, in which C.A.C. also holds an equity interest; receives research/education support through B.W.H. from Cephalon, Mary Ann & Stanley Snider via Combined Jewish Philanthropies, NFL Charities, Jazz Pharmaceuticals Plc Inc, Philips Respironics Inc, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceuticals Industries Ltd, Sanofi SA, Optum, ResMed, San Francisco Bar Pilots, Sanofi, Schneider, Simmons, Sysco, Philips, Vanda Pharmaceuticals; is/was an expert witness in legal cases, including those involving Advanced Power Technologies, Alvarado Hospital, LLC, Amtrak; Bombardier, Inc., C&J Energy Services; Casper Sleep, Inc., Columbia River Bar Pilots, Complete General Construction Company, Dallas Police Department, Delta Airlines/Comair, Enterprise Rent-A-Car, Fédération des Médecins Résidents du Québec (FMRQ), FedEx, Greyhound Lines, Inc./Motor Coach Industries/FirstGroup America, H.G. Energy LLC, Maricopa County, Arizona, Sheriff’s Office, Murrieta Valley Unified School District, Pomerado Hospital, Palomar Health District, Puckett EMS, Purdue Pharma, South Carolina Central Railroad Company, LLC., Steel Warehouse, Inc., Union Pacific Railroad, United Parcel Service, and Vanda Pharmaceuticals; serves as the incumbent of an endowed professorship provided to Harvard University by Cephalon, Inc.; and receives royalties from McGraw Hill, and Philips Respironics for the Actiwatch-2 & Actiwatch Spectrum devices. C.A.C.’s interests were reviewed and are managed by Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Partners HealthCare in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. S.W.L. reports the following interests for the last 5 years (2015–2020). S.W.L. has received consulting fees from Atlanta Falcons, Atlanta Hawks, BHP Billiton, Delos Living LLC, EyeJust Inc., McCullough Hill Leary PS, Noble Insights, OpTerra Energy Services Inc., Pegasus Capital Advisors, Phillips Lytle LLP, Plan LED, Rec Room, Serrado Capital, Slingshot Insights, Stantec and Team C Racing. He has current consulting contracts with Akili Interactive, Apex 2100 Ltd, Consumer Sleep Solutions, Headwaters Inc., Hintsa Performance AG, KBR Wyle Services, Light Cognitive, Lighting Science Group Corporation/HealthE, Look Optic, Mental Workout/Timeshifter, Paul Weiss Rifkind Wharton & Garrison LLP, Six Senses, and View Inc. S.W.L. has received unrestricted equipment gifts from Bionetics Corporation and F.LUX Software LLC; a fellowship gift from Stockgrand Ltd; has equity in iSLEEP, Pty; royalties from Oxford University Press; honoraria plus travel, accommodation and/or meals for invited seminars, conference presentations or teaching from Estée Lauder, Ineos, Informa Exhibitions, MIT, Roxbury Latin School, and Teague; travel, accommodation and/or meals only (no honoraria) for invited seminars, conference presentations, teaching or editorial duties from DIN, Emory University, Lightfair, SLTBR, Solemma and Wiley. S.W.L. has an ongoing investigator-initiated grant from F. Lux Software LLC and a Clinical Research Support Agreement from Vanda Pharmaceuticals Inc. SWL holds a process patent for ‘Systems and methods for determining and/or controlling sleep quality’, which is assigned to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital per Hospital policy, and ‘Method and system for generating and providing notifications for a circadian shift protocol’ held by Mental Workout Inc. S.W.L. has served as a paid expert in legal proceedings related to light, health and work patterns. S.W.L. was the Program Leader for ‘Safety and Productivity Improvements’ in the CRC for Alertness, Safety and Productivity from 2015–2019, through a part-time Adjunct Professor appointment at Monash University, Australia. He currently holds the position of Professor (part-time) and VC Fellow at the University of Surrey, UK. S.W.L.’s interests are reviewed and managed by Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Partners HealthCare in accordance with their conflict of interest policies.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kent, B.A., Rahman, S.A., St. Hilaire, M.A. et al. Circadian lipid and hepatic protein rhythms shift with a phase response curve different than melatonin. Nat Commun 13, 681 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28308-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28308-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.