Abstract

A hallmark of low-temperature plasticity in body-centered cubic (BCC) metals is its departure from Schmid’s law. One aspect is that non-glide stresses, which do not produce any driving force on the dislocations, may affect the yield stress. We show here that this effect is due to a variation of the relaxation volume of the \(1/2\langle 111\rangle\) screw dislocations during glide. We predict quantitatively non-glide effects by modeling the dislocation core as an Eshelby inclusion, which couples elastically to the applied stress. This model explains the physical origin of the generalized yield criterion classically used to include non-Schmid effects in constitutive models of BCC plasticity. We use first-principles calculations to properly account for dislocation cores and use tungsten as a reference BCC metal. However, the methodology developed here applies to other BCC metals, other energy models and other solids showing non-glide effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As stated in 1983 by Christian in the title of his seminal review paper,1 the low-temperature plasticity of body-centered cubic (BCC) metals shows “surprizing features” that, more than 30 years later, are still far from understood. Chief among them is the breakdown of the Schmid law, the fact that contrary to close-packed metals like face-centered cubic (FCC) metals, the plastic yield of BCC metals at low temperatures does not depend only on the resolved shear stress, i.e., the component of the applied stress tensor that produces a shear in the slip plane and along the slip direction. In BCC metals, the yield stress depends not only on the orientation of the shear plane, resulting in the so-called twinning/antitwinning (T/AT) asymmetry, but also on components of the stress tensor that do not drive plastic deformation, called non-glide stresses. It is well-established that non-Schmid effects are due to the core properties of screw dislocations with a \(1/2\langle 111\rangle\) Burgers vector that are responsible for the low-temperature plastic deformation of BCC metals.2,3 The breakdown of the Schmid law is ubiquitous among BCC metals and has been reported both experimentally4,5,6,7,8,9 and in atomic-scale computer simulations of screw dislocations.10,11,12,13,14

So far, non-Schmid effects have been modeled phenomenologically using a generalization of the Schmid law, where the critical stress is written as a linear combination of the stresses that affect dislocation motion.15 In the case of BCC metals, four shear stresses have been found important:16,17,18,19 two stresses resolved in nonparallel planes containing the dislocation Burgers vector to account for the T/AT asymmetry, and two stresses resolved perpendicularly to the Burgers vector for non-glide effects. The generalized yield criterion then depends on a critical stress and three phenomenological parameters that have been fitted on atomistic simulations.14,16,20,21,22 Criteria accounting for more non-glide stresses have also been proposed.29,32 Generalized yield criteria have been used successfully in kinetic Monte Carlo,23 dislocation dynamics,24,25,26 and crystal plasticity21,27,28,29,30,32 simulations. However, the physics behind these yield criteria remains unclear and daunting questions remain unanswered: in particular, can the phenomenological parameters be linked to properties of the screw dislocation? Is there a physical justification for the success of a linear combination of stresses?

Recently, the T/AT asymmetry was physically connected to the systematic departure of the gliding dislocation trajectory away from the straight path connecting equilibrium positions.31 Projecting the applied shear stress onto the deviated trajectory rather than the average glide plane resulted in a modified Schmid law that has the same functional form as the yield criterion. In this way, the phenomenological parameter usually used to express the T/AT asymmetry was explained as reflecting the deviation angle of the dislocation trajectory from the average glide plane.31

Non-glide effects have been studied through atomistic simulations based on interatomic potentials.2,10,13,14,18,32 Their origin was attributed to a coupling between the applied stress tensor and the edge components of the dislocation core field, but the argument remained qualitative and no formal link was ever demonstrated.10 Clouet et al.33,34,35 have shown that the core field corresponds to a short-range dilatation, and can be modeled in anisotropic elasticity by introducing along the dislocation line force dipoles represented by their dipolar moment tensor, or equivalently, a core eigenstrain tensor.36 However, a quantitative link between the dislocation core field and non-glide effects remains to be established.

We show here that non-glide effects result from a variation of the core eigenstrain tensor along the dislocation glide trajectory and can be quantitatively predicted from the elastic coupling between the applied stress tensor and the core eigenstrains. Moreover, we show that the generalized yield criterion derives from a linearization of the dislocation core energy dependence on the applied stress tensor. We employ density functional theory (DFT) first-principles calculations to properly account for dislocation core properties. We consider tungsten, mainly because non-Schmid effects have been studied in this metal using both classical21 and bond-order20 potentials, thus allowing for comparison between energy models. However, the methodology developed here is general and can be applied to all BCC metals and other solids showing non-glide effects.

Results

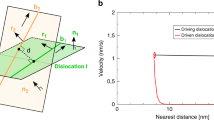

Peierls barrier under a non-glide pure shear stress

We model the energetics of glide of \(1/2\langle 111\rangle\) screw dislocations using the same methodology as in Ref., 31 which relies on three-dimensional periodic boundary conditions.37 As illustrated in Fig. 1, a dipole of straight screw dislocations is introduced along the \(Z\)-axis of the simulation cell. Both dislocations are initially relaxed in their minimum-energy easy core configuration. The left dislocation in Fig. 1 has a Burgers vector \([0,0,-b]\) with \(b=\sqrt{3}/2{a}_{0}\) (\({a}_{0}\) is the lattice parameter) when its line is oriented toward \(Z\,>\,0\). This dislocation is moved to an adjacent easy core position and the corresponding minimum-energy path is computed using the nudged elastic band (NEB) method38 (see the Methods section and Supplementary Section 1 for details). We note that the supercell is invariant by translation in the \(Z\) direction, and all results are therefore independent of the cell size in this direction, which can be reduced to a single Burgers vector. The energy profile shows a barrier, known as the Peierls barrier, which reflects the intrinsic resistance of the BCC lattice to the glide of the screw dislocation. The trajectory followed by the dislocation core in the \(XY\) plane perpendicular to the dislocation lines is obtained from the variation of the internal stress tensor along the path.31,37 We will come back to this point below.

Schematic view of the simulation cell and core eigenstrain model. The cell contains a dipole of screw dislocations separated by a cut surface \({\bf{A}}\) shown in green and a Burgers vector \(1/2[\overline{111}]\). Atoms in different \((111)\) planes appear in different colors. The arrows show the edge displacements produced by the dislocation cores in the \((111)\) plane (magnified by a factor 50). These fields are modeled by representing the dislocation core as a cylindrical Eshelby inclusion schematically represented on the right-hand side

There are different types of non-glide stresses that have in common to produce no Peach–Koehler force on the dislocations. We start with the case of a pure shear perpendicular to the dislocation Burgers vector considered in previous works.10,13,18 When this shear is applied at 45° of the dislocation glide plane, the stress tensor, expressed in the cartesian basis \({\mathscr{B}}\) shown in Fig. 1 with the \(X\)-, \(Y\)-, and \(Z\)-axes parallel to \([\overline{1}\overline{1}2]\), \([1\overline{1}0]\), and \([111]\), respectively, is:

This stress tensor is applied by deforming the simulation cell according to anisotropic linear elasticity. The resulting core trajectories and energy barriers for different magnitudes of \(\sigma\) are shown in Fig. 2a and b. The core trajectories systematically deviate from the average horizontal \((1\overline{1}0)\) glide plane of the dislocation. This deviation has been connected with the T/AT asymmetry31 and will be included in our analysis below, when we consider the coupled effect of non-glide and resolved shear stresses. Figure 2a also evidences that the core trajectory is remarkably unaffected by the non-glide stress. A similar insensitivity of the core trajectory was observed under resolved shear stresses in Ref. 31

DFT calculation of the dislocation core trajectory and energy barrier under a non-glide pure shear stress. a Dislocation trajectory and (b) energy barrier between easy core configurations when no stress is applied (black data and curve) and when either a positive (blue) or a negative (red) non-glide pure shear stress is applied. The symbols are the result of NEB DFT calculations using \(\sigma =\,\pm1.2\) GPa taken as an example. The colored regions show typical regions of variation of the energy barrier when \(\sigma\) is either positive or negative. In (b), the dislocation position \(X\) along the \([\overline{1}\overline{1}2]\) direction is scaled by the distance between Peierls valleys, \(d\)

The energy barriers in Fig. 2b show a pronounced non-glide effect. We note first that since non-glide stresses do not produce a Peach–Koehler force on the moving dislocation, the initial and final configurations have the same energy. We recover also that the lattice resistance increases, i.e. the Peierls barrier is higher, when the \((1\overline{1}0)\) glide plane is in compression and the orthogonal \((\overline{1}\overline{1}2)\) plane is in tension, that is when \({\Sigma }_{22}=-{\Sigma }_{11}=\sigma\, <\,0\). Conversely, the energy barrier decreases and glide is facilitated when \(\sigma\, >\,0\) and the glide plane is in tension. This effect has been systematically observed in studies based on interatomic potentials.10,13,14,18

In the following, the Peierls barrier in absence of applied stress is noted \({V}_{{\rm{P}}}(X)\) and is expressed as a function of the dislocation core position along the \(X\)-axis (the initial easy core position is used as a reference with \(X=Y=0\)).

Eigenstrain model of the dislocation core field and coupling with the applied stress

As illustrated in Fig. 1, screw dislocations in BCC metals induce a short-range dilatation field in addition to the Volterra elastic field.33 We account for this core field by modeling the dislocation core as a cylindrical Eshelby inclusion of surface \({S}_{0}\) and eigenstrain tensor.39,40,41 The effect on stresses and energies depends only on the relaxation volume tensor \(\overline{\overline{\Omega }}\), the product of the inclusion volume with the eigenstrain. Since we model straight infinite dislocations, \(\overline{\overline{\Omega }}\) is defined here per unit length of dislocation. We express it per Burgers vector, \(\overline{\overline{\Omega }}=b\cdot {S}_{0}\overline{\overline{{\epsilon }^{* }}}\), as done for the Peierls barriers in Fig. 2b.

In the easy core position, the dislocation is a center of threefold symmetry. This symmetry imposes that the core eigenstrain tensor is diagonal with equal components perpendicular to the dislocation: \(\overline{\overline{\Omega }}={\rm{diag}}({\Omega }_{11},{\Omega }_{11},{\Omega }_{33})\). The lattice expansion due to the easy core is therefore isotropic in the plane perpendicular to the dislocation line, as also seen in Fig. 1. We will see below that in this case, there is no coupling with the pure shear in Eq. (1). However, along the path away from the initial and final easy core configurations, the threefold symmetry is broken. As a consequence, \({\Omega }_{11}\) and \({\Omega }_{22}\) may be different and the tensor may no longer be diagonal. We have checked, however, (see Supplementary Section 2) that the components \({\Omega }_{13}\) and \({\Omega }_{23}\) are small and can be neglected, at least in tungsten. We will use this simplification here and will consider a relaxation volume tensor of the form:

Following Eshelby’s theory,40,42 if an eigenstrain develops in a system subjected to an applied stress tensor \(\overline{\overline{\Sigma }}\), the energy of the system is changed by the work of the applied stress over the inclusion. This implies that when a dislocation is displaced under the applied stress \(\overline{\overline{\Sigma }}\), the enthalpy per Burgers vector varies as:

where \(\Delta\) symbols were added to indicate that we consider variations with respect to the initial easy core configuration. In the above equation, the first term on the right-hand side is the Peierls barrier in absence of applied stress. The second term is the work of the Peach–Koehler force, where \(\Delta {\bf{A}}\) is the variation of the dipole cut-surface vector (see Fig. 1). In the present calculations, we displace the left dislocation, such that \(\Delta {\bf{A}}=b\cdot (Y,-X,0)\) with \((X,Y)\) the dislocation position with respect to its initial easy core position. When applying the non-glide stress of Eq. (1), this term is zero. The third term is the coupling between the applied stress tensor and the dislocation core eigenstrain and corresponds to a linear dependence of the enthalpy on the applied stress tensor. In case of the pure shear given by Eq. (1), this last term takes the form \(-\sigma (\Delta {\Omega }_{22}-\Delta {\Omega }_{11})\) and may therefore be nonzero only if the in-plane components of \(\overline{\overline{\Omega }}\) are different. Note also that Eq. (3) does not account for the change of elastic interaction between the mobile and immobile dislocations of the dipole. This yields the enthalpy of an isolated dislocation and is consistent with the DFT calculations that are corrected for this energy variation using anisotropic elasticity (see the Methods section).

To compute \(\overline{\overline{\Omega }}\), we take advantage of the fact that, if the energy barriers are computed in simulation cells of fixed shape, a variation of the cut surface of the dipole and/or of the relaxation volume tensor of the moving dislocation induces a variation of the stress tensor:33

The cut-surface term has only \(XZ\) and \(YZ\) components, where \(\overline{\overline{\Omega }}\) was found negligible. As detailed in Supplementary Section 2, this allows to obtain separately \(\Delta {\bf{A}}\) and the four nonzero components of the relaxation volume tensor. The variation of \(\Delta {\bf{A}}\) was used in Fig. 2a to plot the dislocation core trajectories.

The eigenstrain model proposed here is general and does not require any assumption about which stresses affect dislocation mobility. Only the amplitude of the core eigenstrains controls the influence of the corresponding stress components. In the following, we apply this model to tungsten, which will be treated as an anisotropic metal, with no simplification related to its near elastic isotropy.

Application of the eigenstrain model in tungsten

The components of the relaxation volume tensor computed along the Peierls barrier in tungsten in absence of applied stress are shown in Fig. 3a. We see that \(\Delta {\Omega }_{11}\) and \(\Delta {\Omega }_{22}\), which account for the in-plane dilatation of the dislocation core, vary with opposite signs and are symmetric with respect to the middle of the path. In contrast, \(\Delta {\Omega }_{12}\), which represents an in-plane shear of the core, is antisymmetric. As illustrated in Fig. 3b, the core deformation is therefore elliptical and tilted to the right on one side of the path and to the left on the other side. \(\Delta {\Omega }_{33}\) is also symmetric on either sides of the path and negative, which implies a contraction of the core parallel to its line direction. However, \(\Delta {\Omega }_{33}\) remains small compared with \(\Delta {\Omega }_{11}\) and \(\Delta {\Omega }_{22}\). Both the symmetry of \(\Delta {\Omega }_{ii}\) (\(i=1,2,3\)) and antisymmetry of \(\Delta {\Omega }_{12}\) result from the dyad symmetry of the BCC lattice around the \([1\overline{1}0]\) axis. This symmetry imposes that, in absence of applied stress, the dislocation path is symmetric with respect to the Y-axis, and the energy barrier is an even function. The dilatation terms, which also satisfy the dyad symmetry, must therefore also be symmetric even functions. On the other hand, the in-plane shear breaks the symmetry and has its sign reversed when the symmetry is applied. It is therefore an antisymmetric, odd function, equal to zero in the saddle configuration, midway along the path.

Returning to Eq. (3), we can now predict how the Peierls barrier varies under a non-glide stress. We note that the stress variations due to the core eigenstrains induce a correction to the dislocation enthalpy in Eq. (3) of the form \((1/2)\Delta {\sigma }_{ij}\Delta {\Omega }_{ij}\). However, \(| \Delta {\sigma }_{ij}| <\) 150 MPa (see Supplementary Fig. S2) and \(| \Delta {\Omega }_{ij}|\, {<}\, 1 \AA^3b^{-1}\) (see Fig. 3), yielding a correction below 5 10−4 eV b−1, negligible compared with the Peierls barrier.

We fitted \({V}_{{\rm{P}}}\) and the components of \(\overline{\overline{\Omega }}\) as continuous functions using Fourier series and used Eq. (3) to predict the dislocation energy under non-glide stresses. The result is shown as solid lines in Fig. 4a, where we find an almost perfect agreement with the DFT calculations performed for the same applied stresses. In Fig. 4b, we consider other non-glide stresses, the pressure (\(\overline{\overline{\Sigma }}=-P/3\,{\rm{diag}}(1,1,1)\)) and a tension along the dislocation line, \(\overline{\overline{\Sigma }}={\rm{diag}}(0,0,{\Sigma }_{33})\). We find that, in tungsten, with both the DFT calculations and the eigenstrain model, these stresses do not produce any noticeable effect on the Peierls barrier. The reason is that the corresponding eigenstrain components, although nonzero, are small.

Prediction of the effect of non-glide stresses on Peierls barriers. Comparison between the NEB DFT data (symbols) and predictions from the core eigenstrain model (solid lines) in cases of (a) pure shears perpendicular to the dislocation line (Eq. (1)), (b) a pressure and a traction along the dislocation line, and (c) under both resolved and non-glide stresses (σ = −1.2 GPa)

We note that the above predictions do not require any adjustable parameter since the Peierls barrier and relaxation volume tensor are computed on the path with no applied stress and are then used to predict enthalpy barriers under stress. This very good agreement also implies that the core eigenstrain tensor is not affected by the applied stress in the range considered here, or in other words, that the polarization of the dipolar moment tensor of the core is negligible.

Critical resolved shear stress for uniaxial loading

We now consider the case of a uniaxial tension or compression, as done in previous works.10,13,18 The stress tensor produces a resolved shear stress, which is maximum in a plane making an angle \(\chi\) with respect to the \((1\overline{1}0)\) glide plane (see inset in Fig. 5a). Using the fact that, at least in tungsten, neither a pressure nor a tension along the dislocation line affect the Peierls barrier, we can show (see Supplementary Section 3) that, in the frame rotated by \(\chi\), the non-glide stress produced by the uniaxial stress tensor is equivalent to a pure shear as in Eq. (1). In the frame \({\mathscr{B}}\), the applied stress tensor is written as:

The applied resolved shear stress is \(-\tau\) with \(\tau\,>\,0\) to produce a Peach–Koehler force on the moving (left) dislocation in the \(X\,{>}\,0\) direction. We show in Fig. 4c examples of Peierls barriers computed with DFT for different values of \(\tau\) and \(\sigma\) and \(\chi =0\). As before, Eq. (3) is used to predict the Peierls barriers, now including the work of the Peach–Koehler force. The predictions, shown as solid lines in Fig. 4c, follow again very closely the DFT data. Similar overall agreement was obtained for different values of \(\sigma\) and \(\chi\) (see Supplementary Section 4).

Activation enthalpy and Peierls stress. a Examples of variation of the activation enthalpy with resolved shear stress for various non-glide pure shear stresses. b Dependence of the Peierls stress on the non-glide stress \(\sigma\) and the angle \(\chi\) between the plane of maximum shear and the horizontal \((1\overline{1}0)\) glide plane, as illustrated in the inset of (a). In (a), the solid lines are predictions from the eigenstrain model, while the symbols correspond to the values of \(\tau\) and \(\sigma\) considered in the DFT calculations. The symbols in (b) were obtained by extrapolating the core eigenstrain model to zero activation enthalpy for various values of \(\chi\) and \(\sigma\). The solid lines are predictions from Eq. (7)

The agreement between Eq. (3) and the DFT data is accurate enough to use Eq. (3) instead of a numerical fit to extract the activation enthalpy, \(\Delta {{\rm{H}}}^{* }(\chi ,\tau ,\sigma )\), i.e. the maximum of the enthalpy barrier for a given triplet \((\chi ,\tau ,\sigma )\). Examples are shown as symbols in Fig. 5a for \(\chi =0\). However, while the DFT calculation of \(\Delta {{\rm{H}}}^{* }\) can only be run for a finite number of \((\chi ,\tau ,\sigma )\) triplets, Eq. (3) yields a continuous mapping of \(\Delta {{\rm{H}}}^{* }\), which allows us to interpolate between the DFT data in Fig. 5a. As expected, the activation enthalpy decreases as \(\tau\) increases. The critical resolved shear stress at which the enthalpy barrier vanishes is the Peierls stress, \({\tau }_{{\rm{P}}}\), which is reported as symbols in Fig. 5b for the various values of \(\chi\) and \(\sigma\) considered in the DFT calculations. We recover here the generally accepted features of the departure from Schmid’s law: (1) the Peierls stress is asymmetric and is lower in the twinning region where \(\chi\, <\,0\) compared with the antitwinning region where \(\chi\, >\,0\) and (2) the Peierls stress increases when the shear plane is in compression, i.e. when \(\sigma\, <\,0\) and decreases when the shear plane is in tension, i.e. \(\sigma \,>\,0\).

The Peierls stresses in Fig. 5b can be expressed analytically from Eq. (3) in the limit where \(\sigma\) is small enough to perform a first-order expansion. Details are given in Supplementary Section 5, and we only summarize here briefly the main steps. When the stress tensor in Eq. (5) is applied, the dislocation enthalpy per Burgers vector in Eq. (3) becomes:

where we introduced \(\Delta {\Omega }_{{\rm{e}}}=\Delta {\Omega }_{22}-\Delta {\Omega }_{11}\), which describes the ellipticity of the core deformation, and \(\Delta {\Omega }_{{\rm{t}}}=2\Delta {\Omega }_{12}\), its tilt. In agreement with previous work,31 we assimilated the dislocation trajectory to a zig-zag line inclined by an angle \(\alpha\) with respect to the \((1\overline{1}0)\) glide plane. The work of the Peach–Koehler force may then be rewritten as the second term of the right-hand side of Eq. (6). Also, in agreement with the paths shown in Fig. 2 and in Ref., 31 we assume that the trajectory and the angle \(\alpha\) do not depend on the applied stress, i.e. neither on \(\sigma\) nor \(\tau\). For given values of \(\chi\) and \(\sigma\), the Peierls stress \({\tau }_{{\rm{P}}}\) is reached when the enthalpy barrier disappears. There exists then an unstable position \({X}^{* }\) such that \(\Delta {\rm{H}}^{\prime} ({X}^{* })=\Delta {\rm{H}}^{\prime\prime} ({X}^{* })=0\). It can be shown (see Supplementary Section 5) that, to first order in \(\sigma\), we have:

where \({X}_{0}\) is the inflexion point on the Peierls barrier such that \(V^{\prime\prime} ({X}_{0})=0\). Using trigonometry detailed in Supplementary Section 5, this expression can be rewritten in exactly the same form as the generalized yield criterion proposed by Vitek et al.:16

with \({\tau }_{{\rm{CR}}}^{* }\) proportional to \(V^{\prime}_{\rm{P}} ({X}_{0})\), \({a}_{1}=-\sin (\alpha )/ \! \cos (\alpha -\pi /6)\), \({a}_{2}\) proportional to \(\Delta {\Omega}_{\rm{e}}^{\prime}({X}_{0})/\sqrt{3}-\Delta {\Omega }_{{\rm{t}}}^{\prime}({X}_{0})\), and \({a}_{3}\) proportional to \(\Delta {\Omega}_{\rm{e}}^{\prime}({X}_{0})\). The value of the parameters can therefore be computed solely from the Peierls barrier, the dislocation trajectory and the core eigenstrains, all computed in absence of applied stress. The parameters thus obtained are listed in Table 1, and the predicted variations of the Peierls stress as a function of \(\chi\) and \(\sigma\) are shown as solid lines in Fig. 5b. An almost perfect agreement is obtained with the nonlinear predictions obtained by extrapolating Eq. (6) to zero. Table 1 also lists parameters published in the literature for tungsten and obtained by fitting Eq. (8) on atomistic calculations of the Peierls stress based on a bond-order potential (BOP)20 and an embedded atom method (EAM) potential.21

The fact that we can recover the generalized yield criterion from a physical energy model justifies why such a criterion provides an accurate description of the Peierls stress. It also allows to understand physically the meaning of each parameter. In particular, as reported in Ref., 31 the parameter \({a}_{1}\) which accounts for the T/AT asymmetry is a function of \(\alpha\) only, and thus reflects the deviation of the dislocation trajectory between easy core configurations. Also, \({a}_{2}\) and \({a}_{3}\) are linked to the core deformation. More precisely, \({a}_{3}\), which is proportional to \(\Delta {\Omega}_{\rm{e}}^{\prime}({X}_{0})\), reflects the ellipticity of the in-plane core dilatation, while \({a}_{2}\) being proportional to \(\Delta {\Omega}_{\rm{e}}^{\prime}({X}_{0})/\sqrt{3}-\Delta {\Omega }_{{\rm{t}}}^{\prime}({X}_{0})\), depends on both the ellipticity and tilt of the dislocation core.

We have shown that the present eigenstrain model is equivalent to the yield criterion in Eq. (8) when the latter is applicable, i.e. when a uniaxial stress tensor is applied and the pressure and tensile stress along the dislocation line do not affect dislocation mobility. Equation (3) is however more general and can be linearized keeping all the terms. The resulting criterion is equivalent to the formulation proposed by Lim et al.,29 with a straightforward link between their phenomenological parameters and the core eigenstrains. With the notations of Ref., 29 we have \({c}_{1}=-\tan \alpha\), \({c}_{2}=\Delta {\Omega }_{12}^{\prime}({X}_{0})/{b}^{2}\), \({c}_{3}=\Delta {\Omega }_{22}^{\prime}({X}_{0})/{b}^{2}\), \({c}_{4}=\Delta {\Omega }_{11}^{\prime}({X}_{0})/{b}^{2}\), and \({c}_{5}=\Delta {\Omega }_{33}^{\prime}({X}_{0})/{b}^{2}\). Similarly, Koester et al.32 extended Eq. (8) to consider cases where \({\Sigma }_{11}\,\ne \,{\Sigma }_{22}\) and introduced new parameters related to the present framework as \({a}_{4}=\Delta {\Omega }_{22}^{\prime}({X}_{0})/{b}^{2}\), \({a}_{5}=\Delta {\Omega }_{11}^{\prime}({X}_{0})/{b}^{2}\), and \({a}_{6}=\Delta {\Omega }_{33}^{\prime}({X}_{0})/{b}^{2}\).

Discussion

We have shown that non-glide effects on \(1/2\langle 111\rangle\) screw dislocations in tungsten modeled by DFT calculations are due to the elastic coupling between the applied stress tensor and the anisotropic variation of the dilatation induced by the dislocation core during glide. We modeled this dilatation using eigenstrains. This approach shows that, while symmetry imposes that the core dilates isotropically in the plane perpendicular to the dislocation line when the dislocation is in its equilibrium core configuration, away from this configuration, the deformation is anisotropic and tilted as illustrated in Fig. 3b. These core deformations, which couple to the applied stress tensor, affect the energy barrier and in turn the Peierls stress. One consequence is that the systematic softening of the Peierls stress observed when the glide plane is in tension10,13,14,18 is due to the extension of the dislocation core perpendicular to the glide plane reflected by the variation of \(\Delta {\Omega }_{22}\) in Fig. 3a.

The model in Eq. (3) is general, and does not make any assumption about the nature of the non-glide stresses. In the case of tungsten considered here, we have shown that tractions and compressions parallel to the dislocation line and pressure have a negligible effect on dislocation glide. There is however no fundamental reason, such as symmetry, to ensure that this is necessarily the case. From Eq. (3), a traction/compression parallel to the dislocation line couples to the dislocation energy through \(\Delta {\Omega }_{33}\), a pressure couples through \({\rm{Tr}}(\overline{\overline{\Delta \Omega }})/3\), and a pure shear along the \(X\)- and \(Y\)-axes through \(\Delta {\Omega }_{22}-\Delta {\Omega }_{11}\). We can see from Fig. 3 that neither of the first two terms is zero. They are however small compared with the third term, with roughly \(\Delta {\Omega }_{33} \sim -{\rm{Tr}}(\overline{\overline{\Delta \Omega }}) \sim -(\Delta {\Omega }_{22}-\Delta {\Omega }_{11})/8\) for tungsten. For a given amplitude of applied stress, a pure shear has therefore an effect about eight times larger than either a traction/compression parallel to the dislocation line or a pressure, which explains why the Peierls barriers appears unaffected in Fig. 4b.

We have also shown that, when non-glide effects are limited to pure shears perpendicular to the dislocation line, the present eigenstrain model leads to a generalized yield criterion in Eq. (7) with the same functional form as the classical criterion in Eq. (8). This allows to understand the physical origin of this criterion. First, the linear combination of two resolved shear stresses, \(\tau \cos (\chi )+{a}_{1}\tau \cos (\chi +\pi /3)\), which accounts for the T/AT asymmetry, is mathematically equivalent to a projection of the resolved shear stress \(\tau\) on an inclined plane, which corresponds to the deviated dislocation trajectory. Second, the linear combination of stresses resolved perpendicularly to the Burgers vector, \({a}_{2}\sigma \sin (2\chi )+{a}_{3}\sigma \cos (2\chi )\), which accounts for non-glide effects, is a consequence of the linear coupling between the applied stress tensor and the core eigenstrains.

We have determined the parameters to describe non-Schmid effects for the first time from DFT. It is important to stress that these parameters are obtained from a single NEB calculation, the Peierls barrier in absence of applied stress, from which we deduce the Peierls barrier, dislocation trajectory, and core eigenstrains. These zero-stress data are sufficient to predict the dependence of the Peierls stress on the crystal orientation and non-glide stresses. This is possible in particular because the dislocation core trajectory, as defined here from the stress variation, does not depend sensitively on the applied stress tensor, as seen in Fig. 2.

Non-Schmid parameters obtained in this work and with other energy models are listed in Table 1. The BOP potential predicts \({a}_{1}=0\), i.e. no T/AT asymmetry, while the EAM potential predicts \({a}_{1} \sim 1\), i.e. a very strong T/AT asymmetry. The first case corresponds to \(\alpha =0\), i.e. a flat trajectory, while the second case is α ∼ −30°, i.e. a trajectory which passes very close to the atomic column in the twinning region (\(\chi\, <\,0\)) in-between the easy core positions. This is a general tendency of EAM potentials, which underestimate the energy of the dislocation core in the vicinity of the atomic column and may even predict a metastable split core, in contrast with DFT calculations.43,44 In the present DFT calculations, we find an intermediate value, α = −16° and a trajectory, which is neither flat nor close to the split core, as seen in Fig. 2b. This value is more negative than reported in our previous work,31 which is consistent with the larger T/AT asymmetry predicted with the present methodology. The BOP and EAM potentials also find larger values of \({a}_{2}\) and \({a}_{3}\) than DFT. In particular, the EAM potential predicts a very large value of \({a}_{3}\), which physically implies a very large ellipticity and rapid variation of the core deformation with the dislocation position, since \({a}_{3}\) is proportional to \(\Delta \Omega_{\rm{e}}^{\prime}\). The smaller values of \({a}_{2}\) and \({a}_{3}\) found by DFT imply less pronounced non-glide effects. We note that among the different parameters, the \(\alpha\) angle and consequently \({a}_{1}\) are the least well defined quantitatively, in particular in the case of curved paths reported in Fig. 2a. On the other hand, the relaxation volumes and therefore \({a}_{2}\) and \({a}_{3}\) are defined without ambiguity, since they are computed from the stress variation along the Peierls barrier.

The present eigenstrain approach is not limited to straight dislocations, and can be applied to kinked dislocations in order to predict dislocation velocities at finite temperatures. In particular, the elastic coupling term can be included in a stress-dependent Peierls barrier and the methodology proposed in Refs. 45,46 can be used to define a non-glide stress-dependent line tension, to predict non-glide effects on the kink-pair formation enthalpy. Used with a computationally efficient energy model which allows to model long three-dimensional dislocations, the core eigenstrain variation during kink-pair nucleation can also be computed directly and incorporated in a dislocation mobility law.47,48 We note finally that the present approach is not limited to pure BCC metals and can be applied to other systems, which show non-glide effects, such as ordered BCC alloys, as NiTi49 or Fe\({}_{3}\)Al50 and hexagonal metals,51,52 including twinning.53

Methods

Dipoles of \(1/2\langle 111\rangle\) screw dislocations of length \(b\) are modeled in a monoclinic periodic supercell of 135 atoms illustrated in Fig. 1 and described in details in Supplementary Section 1. All calculations were performed with the Vienna ab-initio simulation package (VASP),54 using the generalized gradient approximation with the exchange-correlation functional of Perdew, Burke and Ernzerhof55 and the projector augmented wave (PAW) method with a p-semicore electrons pseudopotential. We applied a kinetic-energy cutoff of 400 eV for the plane-wave basis, a Methfessel–Paxton electronic density broadening of 0.2 eV and a force threshold for ionic relaxations of 5 10−3 eV Å−1. With these parameters, we have along the crystallographic axes, \({C}_{11}=504.1\) GPa, \({C}_{12}=205.7\) GPa, \({C}_{44}=138.7\) GPa. Zener anisotropy factor is \(A=2{C}_{44}/({C}_{11}-{C}_{12})=0.93\), such that tungsten as modeled here is close to, but not exactly, elastically isotropic. The Peierls barriers were computed using a 1 × 2 × 16 k-point mesh in the reciprocal basis \(\{{{\bf{p}}}_{1}^{* },{{\bf{p}}}_{2}^{* },{{\bf{p}}}_{3}^{* }\}\) of the supercell periodicity vectors \(\{{{\bf{p}}}_{1},{{\bf{p}}}_{2},{{\bf{p}}}_{3}\}\) (see Fig. 1). Computing stresses with sufficient accuracy to extract core eigenstrains required a denser k-point mesh, 3 × 3 × 24, generated in the close-to-orthorhombic basis \(\{{{\bf{p}}}_{1}^{* },{{\bf{p}}}_{1}^{* }+{{\bf{p}}}_{2}^{* },{{\bf{p}}}_{3}^{* }\}\) of reciprocal space. Minimum-energy paths were computed in cells of fixed shape using the NEB method as implemented in VASP and a spring constant of 5 eV Å−1. Calculations under stress were done with five images, while the core eigenstrains were obtained with seven images and no applied stress. The energy paths were corrected to account for the variation of elastic interaction energy due to the change of separation between the dislocations using the Babel package.56 The dislocation core trajectories and eigenstrain tensor were extracted from the variation of the internal stress tensor along the NEB path using Eq. (4), as explained above and in Supplementary Section 2.

Data availability

For access to more detailed data than given in the article, please contact the authors.

References

Christian, J. W. Some surprising features of the plastic deformation of body-centered cubic metals and alloys. Metall. Trans. A 14, 1237–1256 (1983).

Duesbery, M. S. On non-glide stresses and their influence on the screw dislocation core in body-centred cubic metals. I. the Peierls stress. Proc. Roy. Soc. London A 392, 145–173 (1984).

Duesbery, M. S. & Vitek, V. Plastic anisotropy in bcc transition metals. Acta Mater. 46, 1481–1492 (1998).

Argon, A. S. & Maloof, S. R. Plastic deformation of tungsten single crystals at low temperatures. Acta Metallurgica 14, 1449–1462 (1966).

Spitzig, W. & Keh, A. The effect of orientation and temperature on the plastic flow properties of iron single crystals. Acta Metallurgica. 18, 611–622 (1970).

Takeuchi, S., Kuramoto, E. & Suzuki, T. Orientation dependence of slip in tantalum single crystals. Acta Metallurgica. 20, 909–915 (1972).

Kitajima, K., Aono, Y. & Kuramoto, E. Slip systems and orientation dependence of yield stress in high purity molybdenum single crystals at 4.2 K and 77 K. Scripta Mater. 15, 919–924 (1981).

Aono, Y., Kuramoto, E. & Kitajima, K. Plastic deformation of high-purity iron single crystals. Rep. Res. Inst. Appl. Mech. 29, 127–193 (1981).

Aono, Y., Kuramoto, E. & Kitajima, K. Orientation dependence of slip in niobium single crystals at 4.2 and 77 K. Scripta Mater. 18, 201–205 (1984).

Ito, K. & Vitek, V. Atomistic study of non-Schmid effects in the plastic yielding of bcc metals. Phil. Mag. A 81, 1387–1407 (2001).

Woodward, C. & Rao, S. I. Flexible ab initio boundary conditions: Simulating isolated dislocations in bcc Mo and Ta. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 216402 (2002).

Chaussidon, J., Fivel, M. & Rodney, D. The glide of screw dislocations in bcc Fe: atomistic static and dynamic simulations. Acta Mater. 54, 3407–3416 (2006).

Gröger, R., Bailey, A. G. & Vitek, V. Multiscale modeling of plastic deformation of molybdenum and tungsten: I. Atomistic studies of the core structure and glide of \(1/2\langle 111\rangle\) screw dislocations at 0 K. Acta Mater. 56, 5401–5411 (2008).

Chen, Z. M., Mrovec, M. & Gumbsch, P. Atomistic aspects of \(1/2\langle 111\rangle\) screw dislocation behavior in \(1/2\langle 111\rangle\) -iron and the derivation of microscopic yield criterion. Mod. Simul. Mat. Sci. Eng. 21, 055023 (2013).

Qin, Q. & Bassani, J. L. Non-Schmid yield behavior in single crystals. J. Mech. Phys. Sol. 40, 813–833 (1992).

Vitek, V., Mrovec, M. & Bassani, J. L. Influence of non-glide stresses on plastic flow: from atomistic to continuum modeling. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 365, 31–37 (2004).

Vitek, V. et al. Effects of non-glide stresses on the plastic flow of single and polycrystals of molybdenum. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 387, 138–142 (2004).

Gröger, R. Which stresses affect the glide of screw dislocations in bcc metals? Phil. Mag. 94, 2021–2030 (2014).

Hale, L. M., Lim, H., Zimmerman, J. A., Battaile, C. C. & Weinberger, C. R. Insights on activation enthalpy for non-Schmid slip in body-centered cubic metals. Scripta Mater. 99, 89–92 (2015).

Gröger, R., Racherla, V., Bassani, J. L. & Vitek, V. Multiscale modeling of plastic deformation of molybdenum and tungsten: II. Yield criterion for single crystals based on atomistic studies of glide of \(1/2\langle 111\rangle\) screw dislocations. Acta Mater. 56, 5412–5425 (2008).

Cereceda, D. et al. Unraveling the temperature dependence of the yield strength in single-crystal tungsten using atomistically-informed crystal plasticity calculations. Int. J. Plast. 78, 242–265 (2016).

Gröger, R. & Vitek, V. Impact of non-Schmid stress components present in the yield criterion for bcc metals on the activity of \(\{110\}\langle 111\rangle\) slip systems. Comp. Mat. Sci. 159, 297–305 (2019).

Stukowski, A., Cereceda, D., Swinburne, T. & Marian, J. Thermally-activated non-Schmid glide of screw dislocations in W using atomistically-informed kinetic monte carlo simulations. Int. J. Plast. 65, 108–130 (2015).

Srivastava, K., Gröger, R., Weygand, D. & Gumbsch, P. Dislocation motion in tungsten: atomistic input to discrete dislocation simulations. Int. J. Plast. 47, 126–42 (2013).

Marichal, C. et al. Origin of anomalous slip in tungsten. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 025501 (2014).

Po, G. et al. A phenomenological dislocation mobility law for bcc metals. Acta Mater. 119, 123–135 (2016).

Yalcinkaya, T., Brekelmans, W. A. M. & Geers, M. G. D. Bcc single crystal plasticity modeling and its experimental identification. Mod. Simul. Mat. Sci. Eng. 16, 085007 (2008).

Weinberger, C. R., Battaile, C. C., Buchheit, T. E. & Holm, E. A. Incorporating atomistic data of lattice friction into bcc crystal plasticity models. Int. J. Plast. 37, 16–30 (2012).

Lim, H., Weinberger, C., Battaile, C. C. & Buchheit, T. E. Application of generalized non-Schmid yield law to low-temperature plasticity in bcc transition metals. Mod. Simul. Mat. Sci. Eng. 21, 045015 (2013).

Patra, A., Zhu, T. & McDowell, D. Constitutive equations for modeling non-Schmid effects in single crystal bcc-Fe at low and ambient temperatures. Int. J. Plast. 59, 1–14 (2014).

Dezerald, L., Rodney, D., Clouet, E., Ventelon, L. & Willaime, F. Plastic anisotropy and dislocation trajectory in bcc metals. Nat. Comm. 7, 11695 (2016).

Koester, A., Ma, A. & Hartmaier, A. Atomistically informed crystal plasticity model for body-centered cubic iron. Acta Mater. 60, 3894–3901 (2012).

Clouet, E., Ventelon, L. & Willaime, F. Dislocation core energies and core fields from first principles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 055502 (2009).

Clouet, E. Dislocation core field. I. Modeling in anisotropic linear elasticity theory. Phys. Rev. B 84, 224111 (2011).

Clouet, E., Ventelon, L. & Willaime, F. Dislocation core field. II. Screw dislocation in iron. Phys. Rev. B 84, 224107 (2011).

Clouet, E., Varvenne, C. & Jourdan, T. Elastic modeling of point-defects and their interaction. Comp. Mat. Sci. 147, 49–63 (2018).

Rodney, D., Ventelon, L., Clouet, E., Pizzagalli, L. & Willaime, F. Ab initio modeling of dislocation core properties in metals and semiconductors. Acta Mater. 124, 633–659 (2017).

Henkelman, G. & Jónsson, H. Improved tangent estimate in the nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths and saddle points. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9978–9985 (2000).

Eshelby, J., Read, W. & Shockley, W. Anisotropic elasticity with applications to dislocation theory. Acta Metallurgica 1, 251–259 (1953).

Eshelby, J. D. The determination of the elastic field of an ellipsoidal inclusion, and related problems. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 241, 376–396 (1957).

Hirth, J. P. & Lothe, J. Anisotropic elastic solutions for line defects in high-symmetry cases. J. Appl. Phys. 44, 1029–1032 (1973).

Mura, T. Micromechanics of Defects in Solids. (Springer, Dordrecht, 1982).

Gordon, P. A., Neeraj, T. & Mendelev, M. I. Screw dislocation mobility in BCC metals: a refined potential description for \(\alpha\)-Fe. Phil. Mag. 91, 3931–3945 (2011).

Dezerald, L. et al. Ab initio modeling of the two-dimensional energy landscape of screw dislocations in bcc transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 89, 024104 (2014).

Proville, L., Ventelon, L. & Rodney, D. Prediction of the kink-pair formation enthalpy on screw dislocations in \(\alpha\)-iron by a line tension model parametrized on empirical potentials and first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 87, 144106 (2013).

Dezerald, L., Proville, L., Ventelon, L., Willaime, F. & Rodney, D. First-principles prediction of kink-pair activation enthalpy on screw dislocations in bcc transition metals: V, Nb, Ta, Mo, W, and Fe. Phys. Rev. B 91, 094105 (2015).

Proville, L., Rodney, D. & Marinica, M. C. Quantum effect on thermally activated glide of dislocations. Nature Mat. 11, 845–849 (2012).

Proville, L. & Rodney, D. Modeling the thermally activated mobility of dislocations at the atomic scale. In Handbook of Materials Modeling: Methods: Theory and Modeling (eds Andreoni, W. & Yip, S.) 1–20 (Springer, Cham, 2018).

Alkan, S., Wu, Y. & Sehitoglu, H. Giant non-Schmid effect in NiTi. Extr. Mech. Lett. 15, 38–43 (2017).

Alkan, S. & Sehitoglu, H. Non-Schmid response of \({{\rm{Fe}}}_{3}\) Al: The twin-antitwin slip asymmetry and non-glide shear stress effects. Acta Mater. 125, 550–566 (2017).

Ostapovets, A. & Vatazhuk, O. Non-Schmid behavior of extended dislocations in computer simulations of magnesium. Comp. Mat. Sci. 142, 261–267 (2018).

Poschmann, M., Asta, M. & Chrzan, D. Effect of non-Schmid stresses on \(\langle a\rangle\)-type screw dislocation core structure and mobility in titanium. Comp. Mat. Sci. 161, 261–264 (2019).

Barrett, C., El Kadiri, H. & Tschopp, M. Breakdown of the Schmid law in homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation events of slip and twinning in magnesium. J. Mech. Phys. Sol. 60, 2084–2099 (2012).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Perdew, J., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Clouet, E. Babel software. http://emmanuel.clouet.free.fr/Programs/Babel.

Acknowledgements

L.D. acknowledges support from LabEx DAMAS (program “Investissements d’Avenir”, ANR-11-LABX-0008-01). D.R. acknowledges support from LabEx iMUST (ANR-10-LABX-0064) of Université de Lyon (program “Investissements d’Avenir”, ANR-11-IDEX-0007). This work was performed using HPC resources from GENCI-CINES computer center under Grant No. A0040906821 and A0040910156 and from PRACE (Partnership for Advanced Computing in Europe) access to AIMODIM project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. performed all calculations. All authors participated in the design of the research, analysis of the data and development of the model. A.K. wrote the initial paper, which was reviewed by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kraych, A., Clouet, E., Dezerald, L. et al. Non-glide effects and dislocation core fields in BCC metals. npj Comput Mater 5, 109 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-019-0247-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-019-0247-3

This article is cited by

-

Finite-temperature screw dislocation core structures and dynamics in α-titanium

npj Computational Materials (2023)

-

Sweep-tracing algorithm: in silico slip crystallography and tension-compression asymmetry in BCC metals

Materials Theory (2022)

-

Repulsion leads to coupled dislocation motion and extended work hardening in bcc metals

Nature Communications (2020)