Abstract

Accurate and efficient predictions of the quasiparticle properties of complex materials remain a major challenge due to the convergence issue and the unfavorable scaling of the computational cost with respect to the system size. Quasiparticle GW calculations for two-dimensional (2D) materials are especially difficult. The unusual analytical behaviors of the dielectric screening and the electron self-energy of 2D materials make the conventional Brillouin zone (BZ) integration approach rather inefficient and require an extremely dense k-grid to properly converge the calculated quasiparticle energies. In this work, we present a combined nonuniform subsampling and analytical integration method that can drastically improve the efficiency of the BZ integration in 2D GW calculations. Our work is distinguished from previous work in that, instead of focusing on the intricate dielectric matrix or the screened Coulomb interaction matrix, we exploit the analytical behavior of various terms of the convolved self-energy Σ(q) in the small q limit. This method, when combined with another accelerated GW method that we developed recently, can drastically speed up (by over three orders of magnitude) GW calculations for 2D materials. Our method allows fully converged GW calculations for complex 2D systems at a fraction of computational cost, facilitating future high throughput screening of the quasiparticle properties of 2D semiconductors for various applications. To demonstrate the capability and performance of our new method, we have carried out fully converged GW calculations for monolayer C2N, a recently discovered 2D material with a large unit cell, and investigate its quasiparticle band structure in detail.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) materials are at the center of materials research in recent years. The intense research activities have resulted in the discovery of an impressive and growing list of 2D materials that were once considered rare and unstable. Among them, 2D semiconductors have received particular attention for their potential use in future electronics and energy related applications. With the increasing role that theory plays in the design and prediction of 2D semiconductors, the importance of accurate understanding of their electronic structures cannot be overstated. Although the GW approximation1,2,3 has been recognized as one of the most accurate theories for predicting the quasiparticle properties of a wide range of materials, straightforward applications of the GW method to 2D materials have been met with multiple computational challenges that make fully converged GW calculations (even at the G0W0 level) rather difficult. These challenges are so grave that, if not properly addressed, they may lead to false theoretical predictions and confusions.

One of the difficulties of 2D GW calculations comes from the Brillouin zone (BZ) integration of the GW self-energy, which is often carried out using discrete summation on a uniform k-grid (N1 × N2 × 1 for 2D systems)

where Σnk(q, ω) is the contribution to the GW self-energy for state \(\left|n{\bf{k}}\right\rangle\) from point q in the BZ, Ω is the volume of the BZ, and fq is the appropriate weight. This summation typically converges rather quickly with respect to the BZ sampling density for bulk (3D) semiconductors. For example, for silicon (diamond structure with a two-atom unit cell), a 6 × 6 × 6 k-grid is sufficient to converge the calculated GW band gap to within 0.01 eV. For 2D materials, however, the convergence is extremely slow. It has been shown that one needs a 24 × 24 × 1 k-grid to properly converge the GW band gap of monolayer MoS24,5,6,7. Although this slow convergence issue is now well understood, it was somewhat unexpected at first. Since the computational cost of GW calculations scales as \(O({N}_{k}^{2})\), where Nk is the number of the BZ integration points, the slow BZ integration convergence issue in 2D GW calculations has significantly hindered practical applications of the GW method for accurate 2D materials predictions.

Compounding matters further is the need to include a large vacuum layer in the modeling of 2D systems using the periodic supercell approach (to minimize the spurious interlayer interactions), resulting in a large cell volume even for relatively simple 2D materials with only a few atoms in the unit cell. This is particularly true for theories (such as the GW method) that involve the calculations of nonlocal interactions or response functions. The calculated quasiparticle energies converge extremely slowly with respect to the vacuum layer thickness d if unmodified long-range Coulomb interaction is used8,9,10. Although the use of truncated Coulomb interaction9,10 greatly expedites the convergence with respect to d, the calculated results still depend on the layer separation (albeit on a much weaker degree), and one still need to include a sizable vacuum layer of about 20 Å or greater for most 2D materials.

The large cell volume translates into the need to include a large number of electronic states in GW calculations. For example, it has been shown4,5,11,12 that one may need to include up to 10,000 conduction bands in the conventional GW calculations even for simple 2D materials with a small unit cell of a few atoms. Note that in order to reach a similar level of convergence, this number scales linearly with the system size (i.e., number of atoms in the unit cell), making fully converged GW calculations for more complex 2D systems extremely difficult using the conventional band-summation approach.

Recently, we developed an accelerated GW approach that can drastically speed up GW calculations for large systems11. In this method, the computationally demanding band summation in conventional GW calculations is replaced by an energy-integration method, resulting in a speedup factor of up to two orders of magnitude for large and/or complex systems, including 2D materials. The slow BZ integration convergence issue, however, still poses a formidable challenge for 2D GW calculations. Considering the importance of accurate predictions of the quasiparticle properties of 2D materials, it is not surprising that there have been several proposed schemes that aim at addressing the slow BZ integration convergence issue, noticeably the work of Rasmussen et al.13 and that of da Jornada et al.7. Motivated by these works, we present here an efficient and accurate yet simple-to-implement method that can significantly reduce the required BZ sampling density for well converged 2D GW calculations. We have tested our method for a range of 2D semiconductors12,14, and, for most cases, the calculated GW quasiparticle energies converge to within 50 meV or less using a very coarse 6 × 6 × 1 k-grid. Combining these two new approaches, we are able to carry out fully converged 2D GW calculations with an overall speed-up factor of over three orders of magnitude compared with the conventional approach.

Results

Analytical behavior of the GW self-energy of 2D systems

The slow BZ integration convergence issue in 2D GW calculations is a manifestation of the asymptotic behavior of Σnk(q, ω) (defined in Eq. 1) in the long wavelength (small q) limit, which is related to the analytical properties of the dielectric function \({\epsilon }_{{\bf{G}}{{\bf{G}}}^{\prime}}^{-1}({\bf{q}},\omega )\), or equivalently, that of the screened Coulomb interaction \({W}_{{\bf{G}}{{\bf{G}}}^{\prime}}({\bf{q}},\omega )\). These quantities vary rapidly as the wave vector q approaches zero, making a simple discrete summation using the uniform sampling scheme very difficult to converge. If we write the BZ summation of the GW self-energy into two parts

it becomes clear that most convergence error comes from the q = 0 term, or, more precisely, the contribution from the mini-BZ centered around the Γ point. In fact, even in conventional GW calculations using a uniform k-grid, the contribution from the q = 0 term has to be treated carefully due to the divergence of the Coulomb interaction. This is typically done by exploiting the analytical behavior of the dielectric matrix and the (truncated) Coulomb interaction at the small q limit and carrying out a mini-BZ averaging of the screened Coulomb matrix, as has been implemented in the BERKELEYGW package and has been discussed in great details in previous works2,9,15.

Figure 1a, b compares the q-dependent head element \({\epsilon }_{00}^{-1}({q}_{\parallel })\) (here, q∥ denotes the wave vector parallel to the atomic plane of the 2D system) of the inverse dielectric matrix of monolayer hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) and that of bulk cubic boron nitride (cBN). The large black dots in the figure correspond to a sampling point in a 6 × 6 × 1 k-grid for the monolayer hBN and that in a 6 × 6 × 6 k-grid for bulk cBN. Whereas \({\epsilon }_{00}^{-1}(q)\) of bulk cBN varies smoothly as q approaches 0, due to the diminishing 2D dielectric screening in the long wavelength limit, there is a sharp upturn of this quantity at small q for the monolayer hBN system. Accurate capturing of such rapid variation would require an extremely dense k-grid if uniform sampling schemes were used. Note that, strictly speaking, the dielectric function for a 2D system calculated using periodic boundary conditions is not a truly 2D dielectric function but that of the 3D model system. It has been shown9, however, that if a truncated Coulomb potential is used, the calculated GW self-energy converges quickly with increasing interlayer separation.

The q-dependent head element of the inverse dielectric matrix of monolayer hexagonal boron nitride is shown in a and that of cubic boron nitride in b. The large black dot in a shows q points included in a 6 × 6 × 1 2D BZ integration grid; that in b shows q points included in a 6 × 6 × 6 grid for cBN. c A 2D hexagonal BZ with a 6 × 6 × 1 uniform k-grid shown with black dots. The gray-shaded area shows the mini-BZ enclosing the Γ point. d The mini-BZ with subsampling points indicated by blue dots.

Therefore, it is compelling to exploit the analytical behavior of the dielectric function and that of the screened Coulomb interaction to achieve converged GW results without the need to use a very high density BZ sampling grid. Rasmussen et al.13 proposed a well-motivated analytical model for the screened Coulomb interaction in the long wavelength limit for 2D systems and carried out the integration of the self-energy in the mini-BZ centered around Γ. Figure 1c shows the BZ of a 2D hexagonal system. A 6 × 6 × 1 uniform sampling grid is shown with black dots in the figure; the shaded area is the mini-BZ centered around the Γ point. Using this method, Rasmussen et al.13 showed that the calculated quasiparticle band gap of monolayer MoS2 converges to about 0.1 eV using a 12 × 12 × 1 k-grid. Although this is a significant achievement, a 12 × 12 × 1 k-grid is still fairly dense, and it is desirable to further reduce the required BZ sampling density. Note that the computation cost of GW calculations scales as \(O({N}_{k}^{2})\), where Nk is the number of the BZ integration points, a small reduction in the k-grid density will result in significant saving of the computation time. For example, by reducing the 2D k-grid density from 12 × 12 × 1 to 6 × 6 × 1, the computational cost would be reduced by a factor of 16.

Finding a compact and reliable analytic model for the response function for a wide range of 2D materials, even in the small q limit, is difficult. Instead of exploiting the analytical behavior of the dielectric function, recently, da Jornada et al.7 proposed a nonuniform subsampling scheme to improve the quality of discreteel at BZ integration. The screened Coulomb interaction matrix in the mini-BZ is approximated by a weighted summation of a few subsampling points in the mini-BZ as shown schematically in Fig. 1d. Using the method, it was shown that the quasiparticle band gap of bilayer MoSe2 converges to within 50 meV using a coarse 2D k-grid of 6 × 6 × 1 with ten subsampling points in the mini-BZ. In both of these methods, a better convergence is achieved with more accurate evaluation of the rapid variation of the screened Coulomb interaction matrix \({W}_{{\bf{G}}{{\bf{G}}}^{\prime}}({\bf{q}})\) within the mini-BZ. However, instead of working on the screened Coulomb interaction matrix, we believe that it is more efficient to exploit the analytical behavior of q-dependent self-energy contribution Σnk(q) directly.

The electron self-energy can be conveniently separated into two parts, a screened exchange (ΣSEX) and a Coulomb hole (ΣCOH) part2; the screened exchange part can be further separated into a bare exchange (ΣX) and a correction term (ΣSX) arising from the screening potential

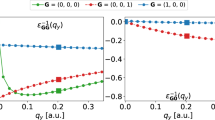

Figure 2 shows these self-energy terms (solid dots) for the valence band maximum (VBM, left panels) and conduction band minimum (CBM, right panels) states of monolayer MoS2 as a function of wave vector q. Note that it is the integration of these contributions over the BZ that gives the self-energy correction for the electronic state (e.g., VBM or CBM) of interest. Interestingly, all these quantities show well-behaved asymptotic properties. Therefore, it is very important to analyze and exploit the analytical behavior of these quantities in the small q limit.

The q-dependent contributions to the self-energy of the VBM are shown in the left panels, and that of the CBM are shown in the right panels. The self-energy is decomposed into three terms of different physical origins as discussed in the text. The large black dots indicate the calculated values at the subsampling q points, and the curves show the fitting functions. The red dots show results calculated at a few additional q points, which agree extremely well with the fitting functions.

We first examine the screened exchange energy for state \(\left|n{\bf{k}}\right\rangle\)

where Mvn(q, k, G) = 〈v, k + q∣ei(q+G)⋅r∣n, k〉 are plane-wave matrix elements between the two states \(\left|v,{\bf{k}}+{\rm{q}}\right\rangle\) and \(\left|n,{\bf{k}}\right\rangle\). It is convenient to write the screened Coulomb potential as the summation of the bare Coulomb potential vb and the screening potential vscr, i.e., W = vb + vscr. Correspondingly, the screened exchange energy can be separated into the bare exchange and a correction coming from the screening potential, i.e., ΣSEX = (ΣX + ΣSX), as mentioned earlier.

The analytical behavior of the bare exchange energy ΣX(q) can then be understood by examining the truncated 2D Coulomb potential9 in the momentum space

where q∥ is the wave vector within the 2D BZ, Lz is periodicity along the z direction, and G∥ (Gz) denotes the G vectors that are parallel (perpendicular) to the 2D atomic layer. The truncated Coulomb potential then approaches 2πL/∣q∥∣ in the small q limit. For simplicity, we will drop the parallel sign (∥) for wave vectors q within the 2D BZ if there are no confusions. Therefore, it is straightforward to speculate that the leading term of the bare exchange energy for the valence (occupied) states has the same asymptotic expression as the bare Coulomb potential. Extending the expression to finite q, for 2D isotropic systems, we have

The solid curve of the top-left panel of Fig. 2 shows a perfect three-parameter fitting of \({\Sigma }_{{\rm{VBM}}}^{{\rm{X}}}(q)\) of monolayer MoS2 calculated on four q points indicated with large black dots. With this fitted expression, the integration of \({\Sigma }_{n{\bf{k}}}^{{\rm{X}}}(q)\) within the mini-BZ can be carried out analytically. Due to the absence of the self-exchange, the bare exchange for conduction (unoccupied) states is much smaller than that for occupied states, and is basically featureless, as shown in the top-right panel of Fig. 2, which can be well fitted with a two- or three-parameter function, i.e.,

using values calculated on four q points as shown with solid curve in the top-right panel of Fig. 2.

The correction to the exchange energy arising from the dielectric screening of the Coulomb potential can also be analyzed. The 2D dielectric function takes the form13,16

in the long wavelength limit, where α2D is the 2D polarizability. Therefore, the screening potential vscr takes the form vscr ≈ 4π2α2D/(1 + 2πα2Dq). Considering the dynamical screening effects, we propose the following analytical form for \({\Sigma }_{n{\bf{k}}}^{{\rm{SX}}}(q,\omega )\) for both valence and conduction states:

The middle panels of Fig. 2 show the three-parameter fittings for ΣSX(q) for the VBM and CBM states of monolayer MoS2 calculated at their respective density functional theory (DFT) energies. Finally, we find that the Coulomb hole self-energy can also be well fitted with the same analytical form, i.e.,

for both the valence and conduction states as shown in the bottom panels of Fig. 2.

We have implemented a nonlinear fitting algorithm (the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm) in our code. We monitor the fitting quality, i.e., the residual error, so one can easily spot possible issues with the fitting procedure. For all systems we have studied, the fitting procedure converges quickly with a reasonable initial guess (e.g., by setting all initial parameters to 1.0). In order to demonstrate the reliability and quality of the proposed fitting functions and that of the implemented fitting algorithm, we have calculated the self-energy at a few additional q points and have added these data points (red dots) to Fig. 2. These additional data points agree well with the functions fitted using the original data (black dots).

Combined subsampling and analytical integration approach

Putting these results together, we propose an approach that has the advantages of both of the previously proposed schemes7,13, a combined subsampling and analytical integration of the self-energy within the mini-BZ, to tackle the convergence issue of the BZ integration in 2D GW calculations. The BZ is sampled with a coarse uniform k-grid as usual; a 6 × 6 × 1 grid is sufficient for most 2D systems with small unit cells. For complex 2D materials with large unit cells, an even coarser k-grid may be used as we will discuss later. We then carry out a few additional sampling points inside the mini-BZ. The three q-dependent GW self-energy terms, namely, ΣX(q), ΣSX(q, ω), and ΣCOH(q, ω) are calculated on these additional sampling points and the results are fitted using the analytical functions discussed in the previous section. The BZ integration of the GW self-energy is separated into two parts, a conventional weighted summation over all k points except the Γ point, and an integration of the fitted analytical functions over the mini-BZ

where Ω0 is the area of the 2D mini-BZ as shown in Fig. 1d.

The self-energy Σnk(q, ω) is typically calculated at two energy points, \(\omega ={\epsilon }_{n{\bf{k}}}^{{\rm{DFT}}}\), and \(\omega ={\epsilon }_{n{\bf{k}}}^{{\rm{DFT}}}+\Delta \epsilon\). A linear expansion2 of the self-energy is then carried out to obtain the self-energy evaluated at the quasiparticle energy, i.e., \({\Sigma }_{n{\bf{k}}}(\omega ={E}_{n{\bf{k}}}^{{\bf{QP}}})\). Since the integration over the mini-BZ is carried out using the fitted analytical functions as opposed to the weighted summation approach, we need only a small number of subsampling points. In fact, for all isotropic 2D systems we have studied, four additional sampling points are sufficient to converge the calculated quasiparticle energy to within 0.01 eV for a given N × N × 1 BZ sampling grid, as discussed in the next section. We mention that our method can be extended to treat anisotropic 2D materials. In this case, the subsampling calculations within the mini-BZ have to be carried out along the two reciprocal lattice directions b1 and b2, and some of the fitting coefficients are vectors instead of scalars. We will report results for anisotropic 2D systems in a separate publication.

Convergence behavior of the GW band gap of monolayer MoS2

We first demonstrate the performance of our method using monolayer MoS2 as an example. The quasiparticle properties of monolayer MoS2 have been investigated by several groups4,5,6,11,17,18. Therefore, this system serves as a good model for testing our methods. Figure 3a shows the calculated minimum direct gap at the k point of monolayer MoS2 as a function of the k-point sampling density. Using the uniform sampling approach, the calculated GW band gap converges to within 0.05 eV with a very dense 24 × 24 × 1 k-grid. Using our approach, the band gap converges to within about 0.02 eV with a 6 × 6 × 1 grid. Note that the spin-orbital coupling effects are not included in the results shown in the figure. As mentioned earlier, the computational cost of the dielectric matrix scales as \(O({N}_{k}^{2})\), where NK is the number of the BZ sampling points. Reducing the k-grid density from 24 × 24 × 1 to 6 × 6 × 1 would ideally result in a speed-up factor of 256. We achieve a speed-up factor of about 200 in real calculations, including the overhead associated with the calculation of the four subsampling q points in the mini-BZ.

a Calculated quasiparticle band gap of MoS2 with respect to increasing BZ sampling density using the conventional uniform sampling method (blue curve) and the current method (red curve). A very coarse 6 × 6 × 1 k-grid with four additional subsampling points in the mini-BZ is sufficient to converge the calculated band gap to within 0.02 eV using our method. The dotted line is guide for the eye, showing the converged value. We also include the results of Rasmussen et al.13 (black solid curve) for comparision. b Calculated band gap of MoS2 using different number of subsampling q points in the mini-BZ. The extremely small variation (±2 meV) likely comes from numerical errors, suggesting that our calculations essentially converge with as few as three subsampling q points.

We include in Fig. 3a the results of Rasmussen et al.13 (black solid curve) for comparision. It should be mentioned that our result seems to agree with that of Rasmussen et al.13 calculated with a 24 × 24 × 1 k-grid. This is a coincidence rather than a confirmation considering various differences (e.g., pseudopotential, crystal structure, and several cutoff parameters) in the two calculations.

We have tested the calculated band gap with respect to the number of subsampling points in the mini-BZ, as shown in Fig. 3b. The result essentially converges with three subsampling q points. The extremely small error (<5 meV) likely comes from numerical errors instead of from the systematic convergence error. We have also tested the sensitivity of the results on the choice of the subsampling q points, and we can confirm that the results are fairly insensitive. Different choices of the subsampling q points within a given N × N × 1 k-grid give practical identical results; the difference is usually within a few meV. This is expected since the calculated self-energy can be fitted extremely well with the proposed functional forms as shown in Fig. 2.

Although the main focus of this work is to address the slow convergence issue of the BZ integration in GW calculations for 2D materials, we would like to discuss other convergence issues in GW calculations. These issues may become another bottleneck for GW calculations for 2D materials. Figure 4a shows the calculated band gap of MoS2 (without including the spin-orbit coupling effects) as a function of the cutoff energy of the dielectric matrix. The calculated band gap does not seem to show a significant dependence on this cutoff parameter, decreasing from 2.62 to 2.56 eV when the cutoff energy is increased from 10 to 75 Ry. A closer look at the convergence behavior of the quasiparticle energies of the VBM and CBM states, however, reveals a rather different picture. The CBM energy decreases by over 0.5 eV, whereas the VBM energy decreases by slightly less than 0.5 eV, within the same parameter range, as shown in Fig. 4b, c. Both the VBM and CBM of MoS2 are primarily derived from the Mo d states, these states share similar wave function characteristics, thus similar convergence behavior. Therefore, the errors largely cancel out, making the calculated band gap appears to depend only weakly on this cutoff parameter. However, if the states of interest have significantly different wave function characteristics, highly converged calculations are necessary, and under-converged calculations may give false predictions for important properties such as transition energies of band offsets.

Our calculations also benefit from the energy-integration method11,19 we developed to speed up the band summation in GW calculations. As we have mentioned earlier, conventional GW calculations for 2D materials require to include a large number of conduction bands, making highly converged calculations even for simple 2D materials containing a few atoms very difficult. The total number of the empty states in our calculations for the monolayer MoS2 is about 25,000, and one needs to include about 10,000 bands to properly converge the band gap (to within 0.01 eV) as shown in Fig. 5a. Using our energy-integration method, we only need about 740 integration (sampling) points to achieve the same level of convergence. Similar to what we have discussed earlier, the change in the calculated band gap with respect to the number of bands included in the GW calculations is much smaller than the change in the VBM (or CBM) quasiparticle energy due to error cancellation, as shown in Fig. 5b. However, there are situations in which highly converged results for the quasiparticle energies (not just the band gap) are required. One of the advantages of our method is that we can afford to include (effectively) all empty states in our GW (both for the dielectric matrix and the self-energy) calculations without the need to concern about the band-summation convergence issue.

Calculated GW band gap (a) and the error in quasiparticle energy of the VBM state (b) as a function of the number of bands included in the calculation. The lower horizontal axis shows the effective number of bands included in our GW calculations, whereas the upper horizontal axis shows the actual number the integration points using our method11.

Quasiparticle band structure of monolayer C2N

In order to further demonstrate the capability and performance of our method, we now investigate the quasiparticle band structure of C2N20, an interesting 2D carbon nitride that is distinguished from other 2D systems by its unique holey structure as shown in Fig. 6. The theoretically optimized lattice constant is 8.29 Å; the three unique bond lengths are shown in the figure. The structure has a large unit cell of 18 atoms, making fully converged GW calculations a real challenge. In fact, C2N has a 2D unit cell area that is equivalent to that of a 24-atom graphene supercell.

The basic electronic structure of monolayer C2N has been studied by several groups21,22,23,24. One interesting feature of the band structure of monolayer C2N is that the top valence bands are nearly dispersion-less if local or semilocal energy functionals within DFT are used. These flat valence bands are primarily derived from nitrogen and carbon px and py orbitals as shown in Fig. 7a, c. The two valence bands immediately below the top two (at the Γ point), in contrast, are mostly derived from carbon pz orbitals with small nitrogen pz components as shown in Fig. 7b, d. Since the in-plane (px and py) states may experience significantly different quasiparticle self-energy corrections compared with the out-of-plane pz states, the ordering of these closely spaced valence bands may change after including GW self-energy corrections, which would have important consequences on the calculated optical and transport properties of this material. In the following, we first discuss the converged quasiparticle band structure of monolayer C2N and discuss its important features compared with that calculated using the local density approximation (LDA). We then discuss several important convergence issues of the GW results.

Figure 8 compares the DFT–LDA and the GW band structures of monolayer C2N. As we have mentioned earlier, the LDA band structure shows two extremely flat top valence bands, which are derived from the in-plane carbon and nitrogen orbitals (px and py) as shown in Fig. 7. The valence bands immediately below the two flat bands are significantly more dispersive and are derived mostly from the out-of-plane carbon pz orbitals. The GW band structure, on the other hand, shows rather dispersive top valence bands. Upon a closer inspection, we find that this difference in the top valence band dispersion comes from the contrasting GW corrections to the out-of-plane (pz) and in-plane states (px and py) as shown in Fig. 9. The px and py derived valence states have significantly larger self-energy corrections compared with those of pz derived states. As a result, the flat topmost valence states calculated within the LDA drop below the pz derived states after including the GW correction. The pz derived states become the topmost valence states and are more dispersive.

To better illustrate the change in the band ordering, we show the zoomed-in band structure around the Γ point in the right panels of Fig. 8. We note that a similar valence band ordering change was observed earlier23 with the use of HSE06 hybrid functional25,26. Interestingly, we find that the band ordering change also occur to the conduction bands (although not as significant as that of valence bands) as shown in the right panels of Fig. 8. These changes in the ordering of the band edge state will have profound impact of the calculated optical and transport properties of this material, which deserve further investigations.

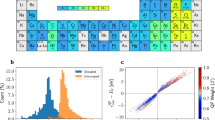

We now discuss several important convergence issues of GW calculations of this material. Figure 10a compares the calculated direct band gap as a function of the BZ integration k-point density using the uniform sampling approach and the current method. Due to its relatively large unit cell (thus a small BZ), the calculated band gap converges to within 0.02 eV using a very coarse 3 × 3 × 1 k-grid, or within 0.01 eV using a 4 × 4 × 1 k-grid, with our BZ integration method. Quasiparticle GW calculations of monolayer C2N have been reported earlier22. The authors used a very small cutoff energy (5 Ry) for the dielectric matrix and included only a few hundred bands in the calculations of the dielectric matrix and the self-energy. The reported GW band gap of monolayer C2N was 3.75 eV22, to be compared with our result of 3.54 eV.

a The calculated GW band gap with respect to BZ sampling density using the conventional uniform sampling method (blue curve) and the method (red curve) proposed in this work. Error in the calculated quasiparticle energy of the VBM state as a function of the cutoff energy of the dielectric matrix (b) and the number of conduction bands included in calculation of the Coulomb hole (COH) self-energy (c). The lower horizontal axis in c shows the number of bands to be included in conventional GW calculations, whereas the upper horizontal axis shows the number of bands plus the integration points used in our method11 to achieve the same level of convergence.

As we have discussed earlier, for many systems, the calculated GW band gap may appear to converge, while the absolute quasiparticle energies for the valence and conduction bands are still not converged. This is because the valence and conduction bands may have the similar convergence behavior, and their difference (which defines the band gap) may appear to converge quickly. In fact, a fairly high kinetic energy cutoff for the dielectric matrix and a large amount of conduction bands are still needed in this case to achieve highly converged results for the quasiparticle energies of this system. Figure 10b shows the convergence behavior of the calculated quasiparticle energy for the VBM state as a function of the kinetic cutoff for the dielectric matrix. If a 5 Ry dielectric matrix cutoff were used, the error in the quasiparticle energy would be about 0.8 eV. A fairly high cutoff energy of 30 Ry is needed to converge the quasiparticle energy to within 0.05 eV. Figure 10c shows the convergence behavior of the calculated quasiparticle energy for the VBM state as a function of the number of conduction bands included in the GW calculations. Over 20,000 bands are needed to converge the calculated quasiparticle energy to within 0.05 eV due to the large cell size of this system. The error in the calculated quasiparticle energy is about 0.95 eV if 1000 bands are included in the calculation. Using the energy-integration method that we developed11,19, we are able to drastically reduce the computation cost associated with the band summation in GW calculations. The values shown on the lower horizontal axis are the number of bands and integration grid points used in our calculations, which shows a speed-up factor of about 30 (20,000/660). Combining this method with the nonuniform BZ integration method discussed in this work, we have achieved a speed-up factor of well over three orders of magnitude.

Discussion

Accurate and efficient GW calculations for 2D materials are met with a multitude of computational challenges. The computational cost of fully converged GW calculations for 2D materials, even for simple materials with small unit cells of a few atoms, can be very expensive, making reliable GW calculations for large and/or complex 2D systems a daunting task. The formidable computational demand has significantly held back the widespread adoption of this otherwise highly successful method for 2D materials predictions.

By carefully investigating the analytical behavior of the GW self-energy, we proposed a combined subsampling and analytical integration method that can greatly improve the efficiency of 2D GW calculations, enabling fast and accurate quasiparticle calculations for complex 2D systems. For most simple 2D materials with a small unit cell of a few atoms, a 6 × 6 × 1 2D BZ sampling grid is sufficient to converge the calculated quasiparticle band gap to within 0.02–0.05 eV, resulting in a speed-up factor of over two orders of magnitude compared with the conventional uniform sampling approach. This method, when combined with another method that we developed earlier11, results in a speed-up factor of well over three orders of magnitude for fully converged GW calculations for 2D materials.

To demonstrate the capability and performance of our method, we have carried out fully converged GW calculations for monolayer C2N, a recently discovered 2D material with a large unit cell of 18 atoms, and investigated its quasiparticle band structure in detail. Our calculations not only provide most converged results but also reveal interesting features of the near-edge electronic properties of this interesting 2D material.

With this development, we can carry out fully converged GW calculations for complex and/or large 2D materials with moderate computational resources that are available to most research groups. We believe that our developments will greatly facilitate future high throughput screening of the quasiparticle properties of 2D semiconductors for various applications. Note that our method only works for 2D semiconductors since the dielectric function and the electron self-energy for 2D metallic systems have different analytical behaviors. In addition, capturing the intra-band transitions in metallic systems may still require a fairly dense k-grid. It would be interesting to find out if current approach can be extended to metallic systems.

Methods

Optimizing the crystal structures and electronic structure methods

We use the crystal structures optimized using the Perdew et al. functional27 for subsequent electronic structure calculations. The optimized lattice constant for MoS2 is 3.18 Å, and the layer thickness (i.e., the S–S interlayer distance) is 3.16 Å. These values are in reasonable agreement with published theoretical results. The detail of the crystal structure of C2N will be discussed later. The monolayer systems are modeled with periodic cells with an interlayer separation of 25 Å. The mean-field electronic structure calculations are carried out using the pseudopotential plane-wave-based DFT method within the LDA as implemented in a local version of the PARATEC package28,29,30. The Perdew and Zunger31 parametrization of the Ceperley and Alder result32 for the electron correlation energy is used. We use the Troullier and Martins norm-conserving pseudopotential33. Semicore 4s and 4p of Mo are included in the calculation. The plans wave cutoff for the DFT and GW calculations for MoS2 is set at 125 Ry; for C2N, it is 70 Ry.

The GW quasiparticle calculations are carried out within the G0W0 (i.e., one-shot GW) approach2 using a local version of the BERKELEYGW package15 in which the method described in this work and a recently developed energy-integration method11,19 are implemented. The summation over the conduction bands in GW calculations is carried out using the energy-integration approach11,19. Using this method, we can effectively include all conduction bands in the calculations at a fraction of the computational cost compared with the conventional band-by-band summation. The kinetic energy cutoff for the dielectric matrix is set at 75 Ry for MoS2 and 40 Ry for C2N. These cutoffs are sufficient to converge the calculated quasiparticle band gap to within 0.02 eV. We use the Hybertsen and Louie generalized plasmon-pole model2 to extend the static dielectric function to finite frequencies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The code developed in this work will be made available from the corresponding author after optimization and on reasonable request.

References

Hedin, L. New method for calculating the one-particle Green’s function with application to the electron-gas problem. Phys. Rev. 139, A796–A823 (1965).

Hybertsen, M. S. & Louie, S. G. Electron correlation in semiconductors and insulators: band gaps and quasiparticle energies. Phys. Rev. B 34, 5390–5413 (1986).

Godby, R. W., Schlüter, M. & Sham, L. J. Self-energy operators and exchange-correlation potentials in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 37, 10159–10175 (1988).

Qiu, D. Y., da Jornada, F. H. & Louie, S. G. Optical spectrum of MoS2: many-body effects and diversity of exciton states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 216805 (2013).

Qiu, D. Y., da Jornada, F. H. & Louie, S. G. Screening and many-body effects in two-dimensional crystals: monolayer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 93, 235435 (2016).

Hüser, F., Olsen, T. & Thygesen, K. S. How dielectric screening in two-dimensional crystals affects the convergence of excited-state calculations: monolayer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 88, 245309 (2013).

da Jornada, F. H., Qiu, D. Y. & Louie, S. G. Nonuniform sampling schemes of the Brillouin zone for many-electron perturbation-theory calculations in reduced dimensionality. Phys. Rev. B 95, 035109 (2017).

Freysoldt, C., Eggert, P., Rinke, P., Schindlmayr, A. & Scheffler, M. Screening in two dimensions: GW calculations for surfaces and thin films using the repeated-slab approach. Phys. Rev. B 77, 235428 (2008).

Ismail-Beigi, S. Truncation of periodic image interactions for confined systems. Phys. Rev. B 73, 233103 (2006).

Rozzi, C. A., Varsano, D., Marini, A., Gross, E. K. U. & Rubio, A. Exact Coulomb cutoff technique for supercell calculations. Phys. Rev. B 73, 205119 (2006).

Gao, W., Xia, W., Gao, X. & Zhang, P. Speeding up GW calculations to meet the challenge of large scale quasiparticle predictions. Sci. Rep. 6, 36849 (2016).

Wu, Y. et al. Quasiparticle electronic structure of honeycomb C3NN: from monolayer to bulk. 2D Mater. 6, 015018 (2018).

Rasmussen, F. A., Schmidt, P. S., Winther, K. T. & Thygesen, K. S. Efficient many-body calculations for two-dimensional materials using exact limits for the screened potential: band gaps of MoS2, h-BN, and phosphorene. Phys. Rev. B 94, 155406 (2016).

Zhang, Y., Xia, W., Wu, Y. & Zhang, P. Prediction of mxene based 2d tunable band gap semiconductors: Gw quasiparticle calculations. Nanoscale 11, 3993 (2019).

Deslippe, J. et al. BerkeleyGW: a massively parallel computer package for the calculation of the quasiparticle and optical properties of materials and nanostructures. Comput. Phys. Commun. 183, 1269 (2012).

Cudazzo, P., Tokatly, I. V. & Rubio, A. Dielectric screening in two-dimensional insulators: implications for excitonic and impurity states in graphane. Phys. Rev. B 84, 085406 (2011).

Shi, H., Pan, H., Zhang, Y.-W. & Yakobson, B. I. Quasiparticle band structures and optical properties of strained monolayer MoS2 and WS2. Phys. Rev. B 87, 155304 (2013).

Molina-Sánchez, A., Sangalli, D., Hummer, K., Marini, A. & Wirtz, L. Effect of spin-orbit interaction on the optical spectra of single-layer, double-layer, and bulk MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 88, 045412 (2013).

Gao, W. et al. Quasiparticle band structures of CuCl, CuBr, AgCl and AgBr: the extreme case. Phys. Rev. B 98, 045108 (2018).

Mahmood, J. et al. Nitrogenated holey two-dimensional structures. Nat. Commun. 6, 6486 (2015).

Zhang, R., Li, B. & Yang, J. Effects of stacking order, layer number and external electric field on electronic structures of few-layer C2N-h2D. Nanoscale 7, 14062 (2015).

Sun, J., Zhang, R., Li, X. & Yang, J. A many-body GW+BSE investigation of electronic and optical properties of C2N. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 133108 (2016).

Gong, S. et al. Tunable half-metallic magnetism in an atom-thin holey two-dimensional C2N monolayer. J. Mater. Chem. C 5, 8424 (2017).

Longuinhos, R. & Ribeiro-Soares, J. Stable holey two-dimensional C2N structures with tunable electronic structure. Phys. Rev. B 97, 195119 (2018).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207 (2003).

Krukau, A. V., Vydrov, O. A., Izmaylov, A. F. & Scuseria, G. E. Influence of the exchange screening parameter on the performance of screened hybrid functionals. J. Chem. Phys. 125, 224106 (2006).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Pfrommer, B. G., Demmel, J. & Simon, H. Unconstrained energy functionals for electronic structure calculations. J. Comput. Phys. 150, 287 (1999).

Pfrommer, B. G., Côté, M., Louie, S. G. & Cohen, M. L. Relaxation of crystals with the quasi-Newton method. J. Comput. Phys. 131, 233 (1997).

Taillefumier, M., Cabaret, D., Flank, A.-M. & Mauri, F. X-ray absorption near-edge structure calculations with the pseudopotentials: application to the K edge in diamond and α-quartz. Phys. Rev. B 66, 195107 (2002).

Perdew, J. P. & Zunger, A. Self-interaction correction to density-functional approximations for many-electron systems. Phys. Rev. B 23, 5048 (1981).

Ceperley, D. M. & Alder, B. J. Ground state of the electron gas by a stochastic method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 566–569 (1980).

Troullier, N. & Martins, J. L. Efficient pseudopotentials for plane-wave calculations. Phys. Rev. B 43, 1993 (1991).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the NSF under Grant Nos DMR-1506669 and DMREF-1626967. P.Z. acknowledges the Southern University of Science and Technology (SUSTech) for hosting his extended visit during spring 2019 when he was on sabbatical. Work at SUSTech and SHU is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos 51632005, 51572167, and 11929401). W.Z. also acknowledges the support from the Guangdong Innovation Research Team Project (No. 2017ZT07C062), Guangdong Provincial Key-Lab program (No. 2019B030301001), Shenzhen Municipal Key-Lab program (ZDSYS20190902092905285), and the Shenzhen Pengcheng-Scholarship Program. We acknowledge the computational support provided by the Center for Computational Research at UB, Beijing Computational Science Research Center, and the Center for Computational Science and Engineering at SUSTech.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.X. was responsible for most of the methodology and code development. W.G. participated in the early stage of the methodology and code development. G.L.-C. and Y.W. carried out some of the calculations and participated in the discussion. W.R. and W.Z. participated in the discussion and provided insightful suggestions. P.Z. was responsible for the original idea and supervised the project. All authors contributed to the manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, W., Gao, W., Lopez-Candales, G. et al. Combined subsampling and analytical integration for efficient large-scale GW calculations for 2D systems. npj Comput Mater 6, 118 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-00385-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-00385-5

This article is cited by

-

Critical assessment of G0W0 calculations for 2D materials: the example of monolayer MoS2

npj Computational Materials (2024)

-

Efficient GW calculations in two dimensional materials through a stochastic integration of the screened potential

npj Computational Materials (2023)

-

Prediction of protected band edge states and dielectric tunable quasiparticle and excitonic properties of monolayer MoSi2N4

npj Computational Materials (2022)