Abstract

Nonlinear optical properties, such as bulk photovoltaic effects, possess great potential in energy harvesting, photodetection, rectification, etc. To enable efficient light–current conversion, materials with strong photo-responsivity are highly desirable. In this work, we predict that monolayer Janus transition metal dichalcogenides (JTMDs) in the 1T′ phase possess colossal nonlinear photoconductivity owing to their topological band mixing, strong inversion symmetry breaking, and small electronic bandgap. 1T′ JTMDs have inverted bandgaps on the order of 10 meV and are exceptionally responsive to light in the terahertz (THz) range. By first-principles calculations, we reveal that 1T′ JTMDs possess shift current (SC) conductivity as large as 2300 nm μA V−2, equivalent to a photo-responsivity of 2800 mA/W. The circular current (CC) conductivity of 1T′ JTMDs is as large as ∼104 nm μA V−2. These remarkable photo-responsivities indicate that the 1T′ JTMDs can serve as efficient photodetectors in the THz range. We also find that external stimuli such as the in-plane strain and out-of-plane electric field can induce topological phase transitions in 1T′ JTMDs and that the SC can abruptly flip their directions. The abrupt change of the nonlinear photocurrent can be used to characterize the topological transition and has potential applications in 2D optomechanics and nonlinear optoelectronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the development of strong light sources, nonlinear optical (NLO) materials have the potential to engender new physical effects. Recently, the generation of nonlinear direct photocurrent upon light illumination has evoked great interest. This is known as bulk photovoltaic effect (BPVE)1. The photocurrent under linearly polarized light, or the shift current (SC), has been theoretically predicted and experimentally observed in materials such as multiferroic perovskites2,3,4,5,6,7 and monolayer monochalcogenides8,9,10. The BPVE is a promising alternative source of photocurrent for energy harvesting and sensing. Compared with the conventional solar cells based on p–n junctions, BPVE is not constraint by the Shockley–Queisser limit11 and can produce open-circuit voltage above the bandgap4. Besides SC, the circular photogalvanic effect12,13,14,15,16 that generates circular current (CC) (aka injection current) under circularly polarized light is another nonlinear photocurrent effect. In time-reversal invariant systems, SC is the response under linearly polarized light, while CC is the response under circularly polarized light. The direction of CC can be effectively controlled by the handedness of the circularly polarized light.

The nonlinear photocurrent effects can be utilized for photodetection, especially in the mid-infrared (MIR) to terahertz (THz) regions, where efficient photodetectors are highly desirable. Compared with traditional infrared detectors such as MCT (HgxCd1−xTe) detector, photodetectors based on nonlinear photocurrent do not require biasing, hence the dark current can be minimized, which is advantageous especially at elevated temperatures. Particularly, topological materials are promising candidates for NLO photodetection. For example, Weyl semimetals (WSMs) have singular Berry curvature around the Weyl nodes, leading to strong linear and nonlinear optical responses17,18,19,20,21,22. Recently, the unoptimized third-order photo-responsivity of WSM TaIrTe4 is reported to be 130.2 mA W−1 under 4 μm wavelength illumination at room temperature21, comparable with that of the state-of-the-art MCT detectors (600 mA W−1) operating at low temperature23,24. Meanwhile, many other WSMs are predicted to have even larger second-order photo-responsivity22. Compared with WSMs in three dimensions (3D), which have vanishing bandgap and may lead to overheating problem under strong light, two-dimensional (2D) topological insulators (TIs) with finite bandgap on the order of 0.01–0.1 eV (within the MIR/THz range) may be a better choice, thanks to their good optical accessibility and easy band dispersion manipulation. (As a matter of nomenclature, despite small bandgap values ~kBTroom, we still call these materials “insulators” due to the literature convention of TIs.) Due to the band inversion, TIs also have augmented Berry connections near the bandgap, which could enhance their optical responses25,26. In this article, we first use a low-energy k · p model to illustrate the guiding principles for designing materials with high nonlinear photoresponse, namely, band inversion, strong spatial inversion asymmetry, and small electronic bandgap. Then, with ab initio calculations, we predict that Janus transition metal dichalcogenides (JTMDs) in the 1T′ phase possess giant nonlinear photoconductivity in the THz range. Being TIs27, 1T′ JTMDs enjoy enhanced optical responses due to the band inversion, and the maximum SC conductivity is found to be around 2300 nm μA V−2 in the THz range. Such colossal SC conductivity is also about tenfolds larger than that of many WSMs22 and other non-centrosymmetric 2D materials, such as 2H TMDs28 and monochalcogenides8,9,10. The CC conductivity of 1T′ JTMDs is also extremely large. The peak value of the CC conductivity is around 8.5 × 103 nm μA V−2, assuming a carrier lifetime of 0.2 ps. Owing to the small bandgap (∼10 meV), the SC conductivity peaks lie within the THz region and quickly decay with increasing light frequency. The inert responsivity to light with higher frequencies renders 1T′ JTMDs selective photodetectors in the THz range. Furthermore, we find that the band topology and Rashba splitting of valence and conduction bands (VB and CB, respectively) of 1T′ JTMDs can be effectively switched/tuned by small external stimuli such as in-plane strain or out-of-plane electric field. We show that such topological phase transition could lead to a sign change of the SC conductivity (and the SC direction) while maintaining its large magnitude. Such a colossal and switchable photocurrent may find applications in 2D optomechanics, nonlinear optoelectronics, etc. In addition, by tuning the Fermi level, the photoconductivity can be further enhanced. Besides nonlinear photoconductivity, other NLO effects, such as second-order harmonic generation, are boosted in JTMDs as well.

Results

A minimal k · p model: guiding principles

In order better illustrate the guiding principles for designing materials with strong nonlinear photoresponses, we first adopt a generic and minimal two-band model that can describe the band-inversion process26 H0(k) = d(k) · σ, where σ = [σx,σy,σz] are Pauli matrices, and \({\mathbf{d}}\left( {\mathbf{k}} \right) = \left[ {Ak_x,\,Ak_y,M - B\left( {k_x^2 + k_y^2} \right)} \right]\), with M, A, and B as model parameters. Without loss of generality, we assume A, B > 0 here. When M > 0, the mass term \(M - B(k_x^2 + k_y^2)\) is positive when \(k_x^2 + k_y^2\) is small and becomes negative when \(k_x^2 + k_y^2\) is large. Hence, there can be a band inversion. On the other hand, when M < 0, the mass term \(M - B(k_x^2 + k_y^2)\) is always negative, and there is no band inversion. In order to obtain finite NLO current responses, the inversion symmetry needs to be broken. Hence, we add an inversion symmetry breaking term HIB = μσx in the model Hamiltonian, where μ is a tunable parameter that controls the strength of the inversion asymmetry and can be likened to, e.g., a static electric field. Finally, px = Aσx and py = Aσy are the momentum operators.

In ref. 26, it was demonstrated that band inversion (M > 0) would boost the linear optical response, because band inversion enhances the interband transition matrix 〈c | r | v〉 (Fig. 1 therein), where |c〉 and |v〉 are the wavefunctions of the CB and VB, respectively, and r is the position operator. This is due to the orbital character mixture when band inversion occurs (e.g., both p and d orbital components are mixed in the VB and CB of 1T′ TMD monolayers27 due to band inversion). Note that | 〈c | r | v〉| determines the response strength of the SC and CC, thus it should be expected that the band inversion would boost the nonlinear photocurrent responses as well.

The shift current conductivity \(\sigma _{xx}^x\) for the model Hamiltonian H(k) = d(k) · σ + μσx, where \({\mathbf{d}}\left( {\mathbf{k}} \right) = [ {Ak_x,\,Ak_y,M - B( {k_x^2 + k_y^2} )}]\) and σ = [σx,σy,σz] are Pauli matrices. a M is varied. For positive and negative M with the same absolute value, \(|\sigma _{xx}^x|\) is larger when M is positive due to band inversion. A = 2, B = 1, μ = 0.1 is used. Blue and red solid curves are \(\sigma _{xx}^x\) for M > 0 and M < 0, respectively. For better visibility, the red solid curve is flipped (red dashed curve, with an extra minus sign) to be compared with the blue curve. b μ is varied. \(\sigma _{xx}^x\) scales approximately linearly with μ, which determines the strength of inversion symmetry breaking. A = 2, B = 1, M = 1 is used.

Then we can calculate the SC response function \(\sigma _{xx}^x\) (we will elaborate on the formula for calculating the SC conductivity later, as in Eq. (2)) for the model Hamiltonian above. We first set A = 2, B = 1, μ = 0.1, and vary M. The results are shown in Fig. 1a. One can see that when M is positive (with band inversion, blue curve), \(\left| {\sigma _{xx}^x} \right|\) is ~3 times larger than that when M is negative (no band inversion, red curves) with the same absolute value |M | . This clearly shows that band inversion can boost the nonlinear photocurrent responses for low frequencies near the bandgap. Besides, one can see that, for positive and negative M, \(\sigma _{xx}^x\) has different signs, indicating that the photocurrents flow in opposite directions25. Another remarkable feature is that, when |M | becomes smaller, the magnitude of the photoconductivity would increase, and there is a rough scaling relation \(\left| {\sigma _{xx}^x} \right|\sim 1/|M|\). Note that, in the current model, |M | measures the bandgap (Eg ∼ 2 | M |). Hence, we suggest that small bandgaps would also boost the nonlinear photoconductivity. We would like to note again that it is the band inversion, rather than the topological nature, that enhances the nonlinear photocurrent. Materials with band inversion can be topologically trivial. Furthermore, the magnitude of the photocurrent response is also dependent on the strength of inversion asymmetry. To elucidate this effect, we fix A = 2, B = 1, M = 1 and vary μ. The results are shown in Fig. 1b. One can see that \(\sigma _{xx}^x\) scales approximately linearly with μ.

The model above suggests that materials with (1) band inversion, (2) strong spatial inversion asymmetry, and (3) small electronic bandgaps may well have large nonlinear photoconductivity. Guided by these principles, we predict that monolayers of JTMDs (denoted as MXY, M = Mo,W, and X,Y = S,Se,Te) in their 1T′ phase possess colossal nonlinear photocurrent conductivity, as we will show in the following. In addition, we would like to remark that the guiding principles stated above are generic regarding all linear and nonlinear optical effects that depend on electron interband transitions, such as second-harmonic generation, etc.

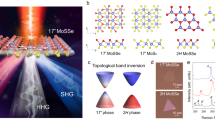

Monolayer JTMDs: atomic and electronic structures

The monolayer JTMDs are composed of three atomic layers: the middle layer of transition metals is sandwiched by two side layers with different chalcogen atoms (Fig. 2). Inherited from pristine TMDs (PTMDs), JTMDs also have different crystalline phase structures. Among them, the 2H and 1T′ are two (meta-)stable structures. The 2H phase JTMDs (space group P3m1, Fig. 2a) have a quasi-Bernal (ABA′) stacking pattern with three-fold in-plane rotational symmetry and have been successfully fabricated recently29,30,31. On the other hand, the 1T′ phase (space group Pm, Fig. 2b) has an ABC stacking pattern, and the in-plane rotational symmetry is broken by a Peierls distortion along the x-axis. With fully relaxed lattice constants, all six MXY have lower energy in 2H phase than in 1T′ phase32, with a small energy difference (≲0.1 eV per formula unit). Similar to the PTMDs, the relative stability of these two phases can be effectively tuned by strain (see Supplementary Fig. 4). For example, we plot the phase diagram of WSeTe in Fig. 2c, which clearly suggests a tensile strain of <1% along the x-axis can render the 1T′ phase more stable. Also, the energy barriers between 2H and 1T′ phases are high (≳1 eV per formula unit), thus 1T′ JTMDs are fairly stable even in the strain-free state.

a, b Atomic structure of 2H and 1T′ phase of JTMD. The black box in b shows the unit cell of 1T′ phase. The top and bottom chalcogens are shifted a bit for better visibility. c The 2H-1T′ phase diagram of WSeTe. a0 and b0 are the fully relaxed lattice constants of the 1T′ phase. The color map indicates the energy difference between 1T′ and 2H phases. 1T′ and 2H phases are energetically favored in red and blue regions, respectively.

The JTMDs inherit many salient properties of PTMDs. As the top–bottom chalcogen layers break the inversion (mirror) symmetry of the 1T′ (2H) phase, JTMDs possess extra properties apart from those of PTMDs, such as larger Rashba spin splitting33,34, more efficient charge separation35, etc. The 1T′ PTMDs are Z2 TIs27 with small bandgaps on the order of 10 meV, indicating a strong optoelectronic coupling in the THz range, because both inverted band structure and small bandgaps would enhance the interband transitions. However, due to the centrosymmetry, the second-order NLO effects are forbidden for 1T′ PTMDs. On the contrary, 1T′ JTMDs are inherently non-centrosymmetric owing to the two different chalcogen layers, and giant second-order NLO effects can be unleashed.

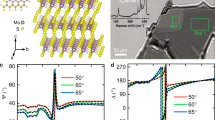

Considering MoSSe as an example, we show the electronic properties of 1T′ JTMDs. The band structure of MoSSe is shown in Fig. 3a. Like PTMDs27, the metal d-orbitals and chalcogen p-orbitals are inverted around the Γ point, and the inverted bandgap is around 0.8 eV. The fundamental bandgaps are along the Γ–Y line (±Λ point, inset of Fig. 3b) with a magnitude of Eg ≈ 4 meV. We find that the fundamental bandgaps of all six 1T′ JTMDs lie in the range of 1–50 meV, corresponding to the THz range (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, despite the band inversion around the Γ point, not all 1T′ JTMD are topologically nontrivial. With fully relaxed atomic structures, MSSe and MSeTe have Z2 = 0 while MSTe have Z2 = 1 (M = W,Mo. Z2 = 0 and 1 indicate trivial and nontrivial band topology, respectively). This is because the large Rashba splitting from the inversion symmetry-breaking could change the band topology by remixing the wavefunctions around the ±Λ point. As we will show later, both in-plane strain and out-of-plane electric field can induce a topological phase transition by closing and reopening the fundamental bandgap36,37,38,39. Regardless of the band topology (Z2 number), the band inversion around Γ point gives rise to a strong wavefunction mixing between VBs and CBs26, which could significantly boost the linear and nonlinear responses.

a Band structure of 1T′ MoSSe, the energy offset is moved to the top of the valence band. Inset: band structure around the fundamental bandgap Λ (along Γ–Y). It is clear that the strong Rashba splitting breaks the twofold degeneracy. b Fundamental bandgaps of all six MXY. Inset: first Brillouin zone of 1T′ JTMDs.

SC and CC

In materials without inversion symmetry \({\cal{P}}\), NLO direct currents (dcs) can be generated upon photo-illumination. This current can be divided into two parts, the SC jSC and the CC jCC

where a, b, c are Cartesian indices and E(ω) is the Fourier component of the optical electric field at angular frequency ω. Equation (1) indicates that, when the optical electric field has both a and b components (a and b can be the same), there will be a dc along the cth direction when \(\sigma _{ab}^c\)/\(\eta _{ab}^c\) is non-zero. In materials with time-reversal symmetry \({\cal{T}}\), the response functions within the independent particle approximation in clean, cold semiconductors are40

Here all dependencies on k are omitted. τ is the carrier lifetime. m, n are band indices, while fmn ≡ fm − fn, ωmn ≡ ωm − ωn, and Δmn ≡ vmm − vnn are the differences in occupation number, energy, and band velocity between bands n and m, respectively. rmn ≡ i〈m | ∇k | n〉 is the interband Berry connection, \(\left[{r_{mn}^a,\,r_{nm}^b}\right]=r_{mn}^ar_{nm}^b-r_{mn}^br_{nm}^a\) is the interband Berry curvature, while rmn;c is the generalized gauge covariant derivative of rmn, defined as \(r_{mn;c}^b = \frac{{dr_{mn}^b}}{{dk_c}} - i\left({\xi _{mm}^c - \xi _{nn}^c}\right)r_{mn}^b,\) where ξmm = i〈um | ∇k | um〉 is the intraband Berry connection and | um〉 is the periodic part of the wavefunction. Equation (2) is slightly different from those in ref. 40 by explicitly including the τ-dependence. Here, for simplicity, we assume the carrier lifetime τ is mode independent and takes a uniform value of τ = 0.2 ps.

When the carrier lifetime satisfies τ ≫ ℏ/Eg, the i/τ term in the denominator of Eq. (2) can be neglected. In this case, \(\sigma _{ab}^c\left( {0;\omega , - \omega } \right)\) is purely real, while \(\eta _{ab}^c\left( {0;\omega , - \omega } \right)\) is purely imaginary. Considering that the dc should be a real quantity, Ea and Eb should have 0 (\(\frac{\pi }{2}\)) phase difference to yield non-vanishing SC (CC), which indicates that SC and CC are responses under linearly and circularly polarized light, respectively. Another noteworthy feature is that, upon light illumination, jCC grows with time at the initial stage, and the saturated static CC should be \(j_{{\mathrm{CC}}} \propto \tau \eta _{ab}^cE^aE^b\), with τ as the carrier lifetime. Therefore τη can be regarded as the effective CC photoconductivity.

Another formula describing the nonlinear photocurrents can be obtained from quadratic Kubo response theory41,42 and reads

Here \(v_{nl} \equiv \left\langle {n|\hat v|l} \right\rangle\) is the velocity matrix element. Equation (2) uses the length gauge, while Eq. (3) uses the velocity gauge. It can be shown (Supplementary Note 2) that, in the presence of time-reversal symmetry \({\cal{T}}\), Eq. (3) is generally equivalent to Eqs. (1) and (2), and the real and imaginary parts of Eq. (3) correspond to the SC and CC, respectively. Compared with Eqs. (1) and (2), Eq. (3) is more general. For example, it can be used to calculate photocurrents in magnetic materials where \({\cal{T}}\) is broken43,44. However, numerically Eq. (3) can experience convergence problems at small ω. Therefore, Eqs. (1) and (2) are adopted for computations in this work, which do not involve magnetism. More detailed discussions on the relationship between Eqs. (1) and (2) and Eq. (3) can be found in Supplementary Notes 1 and 2. The consistency between these two methods is well tested. In practice, the Brillouin zone (BZ) integration is carried out by k-mesh sampling with \(\sigma _{3{\mathrm{D}}} = {\int} {\frac{{{\mathrm{d}}{\mathbf{k}}}}{{\left( {2\pi } \right)^3}}} I({\mathbf{k}}) = \frac{1}{V}\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{\mathbf{k}} {w_{\mathbf{k}}I({\mathbf{k}})}\), where V is the volume of the unit cell, wk is weight factor, and I(k) is the integrand. However, for 2D materials, the definition of volume V is ambiguous, because the thickness of 2D materials is ill-defined45. Thus we replace volume V with the area S and define \(\sigma _{2{\mathrm{D}}} = \frac{1}{S}\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{\mathbf{k}} {w_{\mathbf{k}}I({\mathbf{k}})}\). Note that all ingredients, S, wk and I(k), are well defined and can be directly obtained from numerical computations, hence σ2D is unambiguous for 2D materials. As a result, in this work we mainly show σ2D. The 2D and 3D conductivities satisfy σ2D = Leffσ3D, where Leff should be the effective thickness of the material (not the thickness of the computational cell, which includes the thickness of the vacuum layer). Leff has no standard definitions and is usually set as the interlayer distance when the monolayers are van der Waals stacked along z direction. We use an effective thickness of Leff = 6 Å for JTMDs when σ3D is required for, e.g., the comparison with other materials. Unless explicitly stated, the carrier lifetime is set as τ = 0.2 ps, which should be a conservative value considering that the carrier lifetimes of 2H TMDs are >1 ps at room temperature46,47.

Note that 1T′ JTMDs have mirror symmetry \({\cal{M}}^y\). The yth components of j and E should be flipped under \({\cal{M}}^y\), while other components do not change. Consequently, \({\cal{M}}^y\) enforces \(\sigma _{ab}^c\)/\(\eta _{ab}^c\) to be zero when there is an odd number of y in [a, b, c], such as \(\sigma _{xx}^y\). The different nonzero SC conductivities of 1T′ MoSTe are plotted in Fig. 4a. We observe that both in-plane polarizations \(\sigma _{xx}^x\) and \(\sigma _{yy}^x\) have striking magnitudes of ≳103 nm μA V−2 in the THz range (ω < 10 THz ≈ 41 meV). The peak values of \(\sigma _{xx}^x\) and \(\sigma _{yy}^x\) are around 2300 and 850 nm μA V−2, respectively, more than tenfold larger than those of other non-centrosymmetric 2D materials, such as hexagonal BN (hBN), 2H MoS2, GeS, and SnSe, which are on the order of 10–100 nm μA V−2 (inset of Fig. 4e). When light with intensity 10 mW cm−2 is shining on single layer MoSTe with 1 cm × 1 cm dimension, the photocurrent generated is on the order of 1 nA. Note that the nonlinear photocurrent can be boosted by (1) focusing the light beam and (2) stacking single-layer detectors to increase the cross-section. For example, when the light with the same total power as above is focused onto a 0.01 cm2 spot size, the electric field is enhanced 101×, the photocurrent density would be 102×, and the total photocurrent would be 100 nA. Notably, the SC conductivities quickly decay for ω ≳ 0.1 eV, indicating that 1T′ MoSTe is relatively insensitive to light beyond the THz range, which can be advantageous when selective photodetectors in the THz range are desired. In addition, an interesting observation is that the SC conductivities remain almost constant in the THz range, which could make the calibration of the THz detectors easier. Besides, an in-plane electric field can induce a large photocurrent in the out-of-plane direction: \(\sigma _{xx}^z\) and \(\sigma _{yy}^z\) have peak values of 180 and 25 nm μA V−2, respectively. Such an out-of-plane current can be measured if transparent electrodes like graphene are attached directly above and below the MoSTe monolayer.

a The SC conductivity \(\sigma _{ab}^c(0;\omega , - \omega )\) of MoSTe. b The CC conductivity \(\tau \eta _{ab}^c(0;\omega , - \omega )\) of MoSTe. Inset: the magnitude of the first peak of CC conductivity as a function of carrier lifetime τ. c, d The k-specified contribution to \(\sigma _{xx}^x\) and \(\eta _{xy}^y\). c shows SC(k) at ω = 10 meV while d shows CC(k) at ω = 50 meV. The color maps are in logarithmic scale. kx and ky are in the unit of reciprocal lattices. e, f The peak values of the SC (e) and CC (f) conductivities of six MXY. Inset of e: the peak values of SC conductivities of several other 2D materials, including hBN, 2H MoS2, GeS, and SnSe.

To understand the origin of such giant photoconductivity, the k-specific contribution to the total SC conductivity, \({\mathrm{SC}}\left( {\mathbf{k}} \right) \equiv {\mathrm{Re}}\left\{ {\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{n,m} {f_{nm}\frac{{r_{mn}^ar_{nm;c}^b + r_{mn}^br_{nm;c}^a}}{{\hbar \left( {\omega _{mn} - \omega - i/\tau } \right)}}} } \right\}\) at ω = 10 meV is shown in Fig. 4c. We can see that, around the fundamental bandgap Λ, SC(k) has a peak amplitude of about ±108 Å3 eV−1. Away from Λ, SC(k) rapidly decays. This phenomenon is consistent with the argument that the inverted band structure would lead to enhanced Berry connection magnitudes. We also calculate the SC conductivity for the other five 1T′ JTMDs, and their peak values are shown in Fig. 4e. All of six 1T′ JTMDs possess colossal photovoltaic effect and the peak values of \(\sigma _{xx}^x\) and \(\sigma _{yy}^x\) are on the order of 103 nm μA V−2. Generally, MSTe exhibits stronger BPVE than MSSe and MSeTe. This is due to the larger out-of-plane asymmetry in the MSTe system. The electron affinity of S, Se, and Te atoms are 2.08, 2.02, and 1.97 eV, respectively. Consequently, the out-of-plane asymmetry should be more significant in MSTe, leading to stronger BPV. This point is also verified by the out-of-plane electric dipole Pz. We find that Pz of MSTe is around 0.15 e Å per unit cell, while for MSSe and MSeTe, Pz is only around 0.07–0.08 e Å per unit cell.

The CC conductivities are plotted in the lower panels of Fig. 4 (Fig. 4b, d, f). With in-plane polarization, the only non-vanishing element of the CC tensor is \(\eta _{xy}^y\), based on the symmetry analysis above. \(\tau \eta _{xy}^y\) of MoSTe has a peak value of 8.5 × 103 nm μA V−2 around ω ≈ 50 meV (Fig. 4b). Since \(\tau \eta _{xy}^y\) is sensitively dependent on the carrier lifetime, we vary τ and obtain the peak values of \(\tau \eta _{xy}^y\) (inset of Fig. 4b). Even with τ = 0.04 ps, \(\tau \eta _{xy}^y\) still has a peak value of around 400 nm μA V−2. The k-specific contribution to the total CC conductivity, \({\mathrm{CC}}\left( {\mathbf{k}} \right) \equiv {\mathrm{Re}}\left\{ {\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{n,m} {f_{nm}\frac{{{{\Delta }}_{mn}^c\left[ {r_{mn}^a,\,r_{nm}^b} \right]}}{{\omega _{mn} - \omega - i/\tau }}} } \right\}\) at ω = 50 meV, is plotted in Fig. 4d. Similar to SC, the major contributions also lie in the vicinity of Λ. Finally, the peak values of \(\tau \eta _{xy}^y\) for all six 1T′ JTMDs are shown in Fig. 4f. Similar as in SC, the CC conductivity in MSTe, which has stronger spatial inversion asymmetry, is stronger than those in MSSe and MSeTe. Here we would like to mention that besides SC and CC, which are interband contributions to the nonlinear photocurrent, there could also be intraband contributions. For insulating materials at zero temperatures, the intraband part should be zero. But since 1T′ JTMDs have small bandgaps comparable with room temperature (kBTroom ~ 26 meV), we have also calculated the intraband contribution due to anomalous velocity at finite temperatures. The results are shown in Supplementary Discussion 1, and one can find that the intraband contributions can be on the same order as the interband contributions.

Topological phase transitions

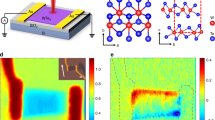

As discussed above, around the ±Λ points, the Rashba splitting breaks the degeneracy and could close and reopen the bandgap, leading to topological phase transitions. The magnitude of the Rashba splitting could be engineered with external stimuli, such as in-plane strain, external electric field, etc. For example, with a tensile strain, the vertical distance between two chalcogen layers of 1T′ JTMD shrinks (inset of Fig. 5a). The bandgap of MoSSe as a function of biaxial in-plane strain ϵ is plotted in Fig. 5a, where a band closing occurs around ϵ = 0.3%. This band closing/reopening indicates a topological transition. For ϵ < 0.3%, 1T′ MoSSe has trivial band topology with Z2 = 0, while with ϵ > 0.3%, 1T′ MoSSe becomes a Z2 TI. Such sensitive dependence on in-plane strain provides a convenient pathway to trigger topological phase transitions in 1T′ JTMD. An even more intriguing phenomenon arises in the SC responses. In Fig. 5b, we show the SC conductivity of 1T′ MoSSe as the function of ϵ. All four components of \(\sigma _{ab}^c\) undergo an abrupt jump upon the topological transition. Particularly, \(\sigma _{xx}^x\) and \(\sigma _{xx}^z\) flip their directions. Such an abrupt jump originates in the change in the band characteristics around Λ upon the topological transition25. As discussed above, the major contributions to the total SC conductivity come from k-points around Λ point (Fig. 3b). When the bandgap is closed and reopened, the wavefunctions of the lowest CB and highest VB around Λ point undergo a substantial remixing. In ideal cases such as the aforementioned two-band model, \(I_{mn;c}^{ab} = r_{mn}^ar_{nm;c}^b + r_{mn}^br_{nm;c}^a\) would flip sign since m and n is interchanged and \(I_{mn;c}^{ab}\) is purely imaginary. When more band contributions are incorporated, \(I_{mn;c}^{ab}\) does not always flip its sign but would still experience a drastic change. The arguments above are verified by the k-specific contribution to \(\sigma _{xx}^x\) and \(\sigma _{yy}^x\) as shown in Fig. 5c–f, where we can see that SC(k) are significantly different on two sides of the topological transition. In addition to in-plane strain, an out-of-plane electric field, which also modifies the magnitude of the Rashba splitting, can trigger the topological transition and alter the SC conductivities as well (see Supplementary Fig. 6 and 7). Thus we propose that the abrupt jump of nonlinear photocurrent can be a universal signature of the topological phase transition in non-centrosymmetric materials and can be used as an online diagnostic tool. The mechanical, electrical, and even optomechanical48,49 approaches to switching the NLO responses would pave the way for efficient and ultrafast nonlinear optoelectronics.

a The bandgap of 1T′ MoSSe as a function of biaxial in-plane strain ϵ. When ϵ < 0.3%, 1T′ MoSSe is topologically trivial, while for ϵ > 0.3%, it is a Z2 topological insulator. Inset: the atomic thickness of 1T′ MoSSe as a function of ϵ. The vertical chalcogen distance shrinks with tensile strain, thus altering the magnitude of the Rashba splitting. b The SC conductivities of MoSSe as a function of ϵ. There are abrupt jumps when MoSSe goes through the topological transition and \(\sigma _{xx}^x\) and \(\sigma _{xx}^z\) flip directions. This effect can be understood with the k-specified contribution to the total SC conductivity SC(k) in c–f.

Fermi-level tuning

It is also interesting how the nonlinear photocurrents vary when the Fermi level is buried in the CB or VB by carrier doping. The SC and CC conductivities of MoSTe as the function of the Fermi level EF are shown in Fig. 6a. We can see that for EF within ±50 meV (EF is set as 0 when the Fermi level is on the top of the VB), the SC and CC conductivities remain extremely large in their magnitudes, while for EF far away from the fundamental bandgap (heavily carrier doped), both SC and CC conductivities gradually decay to zero. Here the pure intraband nonlinear anomalous Hall current discussed above50 is not considered. A noteworthy feature is that, when EF is slightly above (below) the bandgap, \(\sigma _{yy}^x\) would jump to an enormously positive (negative) value, about ten times larger in amplitude than that when EF is inside the bandgap. This effect can be understood by looking at the band structure (Fig. 3a) and the k-specific contribution SC(k) (Fig. 4c). As discussed above, the major contribution to the total SC conductivity comes from k-points close to the fundamental bandgap Λ. When the VB and CB are occupied and empty, respectively, SC(Λ + δky) and SC(Λ − δky) (δ is a small positive parameter) have opposite values and tend to cancel each other. On the other hand, with a positive EF, those CB below the Fermi level would be occupied as well, and the CB–VB transition cannot contribute to SC(k) anymore (Fig. 6b). However, a lager region on the Λ − δky side would have occupied CB than on the Λ + δky side. This is because the CB cone is tilted and the band velocity is smaller on the Λ − δky side, leading to a larger partial density of states in this region. As a result, the positive SC(k) on the Λ + δky side would be canceled less by the negative SC(k) on the Λ − δky side, leading to a larger total SC conductivity (Supplementary Fig. 8 and 9). A similar analysis could show that, when EF is within the VB, the total SC would have a significant negative value. These observations indicate that the photocurrent conductivity could be further enhanced by Fermi-level tuning in materials with tilted CB and/or VB, such as type-II WSM51. From Fig. 6a, one can see that an ~1 meV shift in EF can dramatically enhance \(\sigma _{yy}^x\). In practice, EF can be tuned by, e.g., gate voltage. Assuming a gate coupling efficiency of 0.1, then an ~10 mV gate voltage would be able to achieve the enhancement.

Discussion

Before concluding, we would like to note that, in addition to nonlinear photocurrents, other NLO effects such as the second-harmonic generation are also colossal in 1T′ JTMDs (Supplementary Fig. 10). Besides, the inversion symmetry of 1T′ PTMDs can be broken externally by, e.g., an out-of-plane electric field, resulting in nonlinear photocurrents, which can be regarded as a third-order nonlinear effect. The SC conductivity can be giant as well and can flip direction under a vertical electric field (Fig. 7). Also, the SC conductivity depends approximately linearly on the electric field, which characterizes the strength of inversion asymmetry. This is consistent with results with the model Hamiltonian before, when μ plays a similar role as the electric field. In addition, we find that the reflectance and absorbance of 1T′ JTMDs are small (Supplementary Discussion 2), as they are atomically thin monolayers.

a The SC conductivity of 1T′ pristine MoS2 as a function of out-of-plane electric field. The out-of-plane electric field breaks the inversion symmetry and the photocurrent flip direction when the direction of the electric field is flipped. Inset b: A schematic illustration of the system: A PTMD is under an out-of-plane electric field +Ez. A light polarized in y direction shines on the PTMD and a current in the +x direction jx is induced from the non-zero \(\sigma _{yy}^x\). The direction of the current would flip to −x if the out-of-plane electric field is flipped to −Ez. Inset c: bandgap of 1T′ MoS2 as a function of out-of-plane electric field.

In conclusion, we reveal the colossal nonlinear photocurrent effects in 1T′ JTMDs. The photo-responsivity peaks within the THz range. As a result, the 1T′ JTMDs can be efficient and selective photodetectors in the THz range. We also investigate the topological order of 1T′ JTMDs and find that it can be conveniently switched by a small external stimulus such as in-plane strain and out-of-plane electric field. Upon the topological transitions, the photocurrents undergo an abrupt change and can flip direction, which can be used as a signal of the topological transition and can lead to sensitive manipulation of NLO effects. The colossal and switchable nonlinear photocurrents could find broad applications in photodetection, nonlinear optoelectronics, optomechanics, etc.

Methods

Ab initio calculations

The first-principles calculations are based on density functional theory (DFT)52,53, as implemented in Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)54,55. Generalized gradient approximation in the form of Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof56 is used to treat the exchange–correlation interactions. Core and valence electrons are treated by projector augmented wave method57 and a plane wave basis set with a cutoff energy of 520 eV, respectively. For the DFT calculations, the first BZ is sampled by a Γ-centered k-mesh with grid density of at least 2π × 0.02 Å−1 along each dimension. For the electric field calculations, a sawtooth-like potential along the z direction is applied, with discontinuity at the middle of the vacuum layer in the simulation cell. The symmetry constraints are completely switched off in all VASP calculations to avoid incorrect handling of the electric field58. To further test the correctness of the bandgap–electric field relationship, we have redone the calculations with Quantum Espresso59, and the results agree well with that of VASP.

Wannier function fittings

The Bloch wavefunctions from DFT calculations are projected onto the maximally localized Wannier functions (MLWF) with the Wannier90 package60. The MLWFs |nR〉 are defined as

where |mk〉 are the Bloch wavefunctions as obtained in the DFT calculations, R are Bravais lattice vectors, J is the number of Wannier bands, and \(U_{mn}^{\mathbf{k}}\) is a unitary transformation such that the Wannier functions are maximally localized. The Wannier Hamiltonian HW is constructed from the MLWFs, with

Wannier Hamiltonian in the k space can be obtained with a Fourier transformation

where we have included the Wannier centers rm in the phase factor61,62. By diagonalizing \(H_{nm{\boldsymbol{k}}}^W\) at each k-point, one obtains the energy and wavefunctions \(E_n^W({\mathbf{k}})\) and |nk〉W.

Band velocity, Berry connection, and sum rule

The Wannier Hamiltonian and wavefunctions are directly applied to calculate the band velocity vmn with

Then the interband Berry connections rmn can be obtained with the relation

And the generalized gauge covariant derivative of rmn is calculated with the sum rule9,28,61

where \(\Delta_{\mathrm{nm}}=v_{nn}-v_{mm}\) and \(w_{nm}^{ab} = \left\langle {n|\frac{{\partial ^2H}}{{\partial k_a\partial k_b}}|m} \right\rangle ^W\).

Nonlinear photoconductivity

After all the ingredients, \(v_{mn}^a,\,r_{mn}^a\), and \(r_{mn;b}^a\), are obtained from the Wannier interpolations, the nonlinear photoconductivity is calculated based on Eq. (2) in the main text. The BZ integration is sampled with a 1601 × 3201 k-mesh in the first BZ. The k-mesh convergence is tested with a denser 2251 × 4501 k-mesh, and the difference is found to be negligible (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Code availability

The data that support the findings within this paper and the MATLAB code for calculating the shift and circular current conductivity are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Fregoso, B. M. Bulk photovoltaic effects in the presence of a static electric field. Phys. Rev. B 100, 064301 (2019).

Qin, M., Yao, K. & Liang, Y. C. High efficient photovoltaics in nanoscaled ferroelectric thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 122904 (2008).

Choi, T., Lee, S., Choi, Y. J., Kiryukhin, V. & Cheong, S. W. Switchable ferroelectric diode and photovoltaic effect in BiFeO3. Science 324, 63–66 (2009).

Yang, S. Y. et al. Above-bandgap voltages from ferroelectric photovoltaic devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 143–147 (2010).

Daranciang, D. et al. Ultrafast photovoltaic response in ferroelectric nanolayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 087601 (2012).

Grinberg, I. et al. Perovskite oxides for visible-light-absorbing ferroelectric and photovoltaic materials. Nature 503, 509–512 (2013).

Bhatnagar, A., Roy Chaudhuri, A., Heon Kim, Y., Hesse, D. & Alexe, M. Role of domain walls in the abnormal photovoltaic effect in BiFeO3. Nat. Commun. 4, 2835 (2013).

Rangel, T. et al. Large bulk photovoltaic effect and spontaneous polarization of single-layer monochalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 067402 (2017).

Cook, A. M., Fregoso, B. M., De Juan, F., Coh, S. & Moore, J. E. Design principles for shift current photovoltaics. Nat. Commun. 8, 14176 (2017).

Wang, H. & Qian, X. Ferroicity-driven nonlinear photocurrent switching in time-reversal invariant ferroic materials. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav9743 (2019).

Shockley, W. & Queisser, H. J. Detailed balance limit of efficiency of p-n junction solar cells. J. Appl. Phys. 32, 510–519 (1961).

McIver, J. W., Hsieh, D., Steinberg, H., Jarillo-Herrero, P. & Gedik, N. Control over topological insulator photocurrents with light polarization. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 96–100 (2012).

Yuan, H. et al. Generation and electric control of spin-valley-coupled circular photogalvanic current in WSe2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 851–857 (2014).

Dhara, S., Mele, E. J. & Agarwal, R. Voltage-tunable circular photogalvanic effect in silicon nanowires. Science 349, 726–729 (2015).

Ji, Z. et al. Spatially dispersive circular photogalvanic effect in a Weyl semimetal. Nat. Mater. 18, 955–962 (2019).

De Juan, F., Grushin, A. G., Morimoto, T. & Moore, J. E. Quantized circular photogalvanic effect in Weyl semimetals. Nat. Commun. 8, 15995 (2017).

Morimoto, T. & Nagaosa, N. Topological nature of nonlinear optical effects in solids. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501524 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Photogalvanic effect in Weyl semimetals from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 97, 241118 (2018).

Wu, L. et al. Giant anisotropic nonlinear optical response in transition metal monopnictide Weyl semimetals. Nat. Phys. 13, 350–355 (2017).

Osterhoudt, G. B. et al. Colossal mid-infrared bulk photovoltaic effect in a type-I Weyl semimetal. Nat. Mater. 18, 471–475 (2019).

Ma, J. et al. Nonlinear photoresponse of type-II Weyl semimetals. Nat. Mater. 18, 476–481 (2019).

Xu, Q. et al. Comprehensive scan for nonmagnetic Weyl semimetals with nonlinear optical response. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 32 (2020).

Theocharous, E., Ishii, J. & Fox, N. P. A comparison of the performance of a photovoltaic HgCdTe detector with that of large area single pixel QWIPs for infrared radiometric applications. Infrared Phys. Technol. 46, 309–322 (2005).

Rogalski, A., Antoszewski, J. & Faraone, L. Third-generation infrared photodetector arrays. J. Appl. Phys. 105, 091101 (2009).

Tan, L. Z. & Rappe, A. M. Enhancement of the bulk photovoltaic effect in topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 237402 (2016).

Xu, H., Zhou, J., Wang, H. & Li, J. Giant photonic response of Mexican-hat topological semiconductors for mid-infrared to terahertz applications. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 6119–6126 (2020).

Qian, X., Liu, J., Fu, L. & Li, J. Quantum spin Hall effect in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Science 346, 1344–1347 (2014).

Wang, C. et al. First-principles calculation of nonlinear optical responses by Wannier interpolation. Phys. Rev. B 96, 115147 (2017).

Lu, A. Y. et al. Janus monolayers of transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 744–749 (2017).

Zhang, J. et al. Janus monolayer transition-metal dichalcogenides. ACS Nano 11, 8192–8198 (2017).

Zheng, B. et al. Band alignment engineering in two-dimensional lateral heterostructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 11193–11197 (2018).

Li, W. & Li, J. Ferroelasticity and domain physics in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers. Nat. Commun. 7, 10843 (2016).

Cheng, Y. C., Zhu, Z. Y., Tahir, M. & Schwingenschlögl, U. Spin-orbit–induced spin splittings in polar transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers. Europhys. Lett. 102, 57001 (2013).

Li, F. et al. Intrinsic electric field-induced properties in Janus MoSSe van der Waals structures. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 559–565 (2019).

Riis-Jensen, A. C., Pandey, M. & Thygesen, K. S. Efficient charge separation in 2D Janus van der Waals structures with built-in electric fields and intrinsic p-n doping. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 24520–24526 (2018).

Murakami, S. Phase transition between the quantum spin Hall and insulator phases in 3D: emergence of a topological gapless phase. New J. Phys. 9, 356 (2007).

Murakami, S. & Kuga, S. I. Universal phase diagrams for the quantum spin Hall systems. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 78, 165313 (2008).

Yang, B. J. & Nagaosa, N. Classification of stable three-dimensional Dirac semimetals with nontrivial topology. Nat. Commun. 5, 4898 (2014).

Murakami, S., Iso, S., Avishai, Y., Onoda, M. & Nagaosa, N. Tuning phase transition between quantum spin Hall and ordinary insulating phases. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 76, 205304 (2007).

Hughes, J. L. P. & Sipe, J. Calculation of second-order optical response in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 53, 10751–10763 (1996).

Kraut, W. & Von Baltz, R. Anomalous bulk photovoltaic effect in ferroelectrics: a quadratic response theory. Phys. Rev. B 19, 1548–1554 (1979).

Von Baltz, R. & Kraut, W. Theory of the bulk photovoltaic effect in pure crystals. Phys. Rev. B 23, 5590–5596 (1981).

Zhang, Y. et al. Switchable magnetic bulk photovoltaic effect in the two-dimensional magnet CrI3. Nat. Commun. 10, 3783 (2019).

Fei, R., Song, W. & Yang, L. Giant linearly-polarized photogalvanic effect and second harmonic generation in two-dimensional axion insulators. Phys. Rev. B 102, 035440 (2020).

Laturia, A., Van de Put, M. L. & Vandenberghe, W. G. Dielectric properties of hexagonal boron nitride and transition metal dichalcogenides: from monolayer to bulk. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2, 1–7 (2018).

Wang, H., Zhang, C. & Rana, F. Surface recombination limited lifetimes of photoexcited carriers in few-layer transition metal dichalcogenide MoS2. Nano Lett. 15, 8204–8210 (2015).

Niehues, I. et al. Strain control of exciton-phonon coupling in atomically thin semiconductors. Nano Lett. 18, 1751–1757 (2018).

Zhou, J., Zhang, S. & Li, J. Normal-to-topological insulator martensitic phase transition in group-IV monochalcogenides driven by light. NPG Asia Mater. 12, 2 (2020).

Xu, H., Zhou, J., Li, Y., Jaramillo, R. & Li, J. Optomechanical control of stacking patterns of h-BN bilayer. Nano Res. 12, 2634–2639 (2019).

Wang, H. & Qian, X. Ferroelectric nonlinear anomalous Hall effect in few-layer WTe2. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 119 (2019).

Soluyanov, A. A. et al. Type-II Weyl semimetals. Nature 527, 495–498 (2015).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871 (1964).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133–A1138 (1965).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Liu, Q. et al. Tuning electronic structure of bilayer MoS2 by vertical electric field: a first-principles investigation. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 21556–21562 (2012).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Mostofi, A. A. et al. An updated version of wannier90: a tool for obtaining maximally-localised Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 2309–2310 (2014).

Ibañez-Azpiroz, J., Tsirkin, S. S. & Souza, I. Ab initio calculation of the shift photocurrent by Wannier interpolation. Phys. Rev. B 97, 245143 (2018).

Železný, J., Zhang, Y., Felser, C. & Yan, B. Spin-polarized current in noncollinear antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 187204 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Office of Naval Research Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative Award No. ONR N00014-18-1-2497. Y. G. and J. K. acknowledge the support from U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences (BES) under Award DE-SC0020042.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. and H.X. conceived the idea and designed the project. H.X. performed the ab initio calculations. H.X., H.W., J.Z., and Y.G. analyzed the data. J.L. and J.K. supervised the project. All authors wrote the paper and contributed to the discussions of the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, H., Wang, H., Zhou, J. et al. Colossal switchable photocurrents in topological Janus transition metal dichalcogenides. npj Comput Mater 7, 31 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-021-00499-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-021-00499-4

This article is cited by

-

Shift current response in elemental two-dimensional ferroelectrics

npj Computational Materials (2023)

-

Giant room-temperature nonlinearities in a monolayer Janus topological semiconductor

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Abnormal nonlinear optical responses on the surface of topological materials

npj Computational Materials (2022)

-

Photo-magnetization in two-dimensional sliding ferroelectrics

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2022)