Abstract

The promise enabled by boron arsenide’s (BAs) high thermal conductivity (κ) in power electronics cannot be assessed without taking into account the reduction incurred when doping the material. Using first principles calculations, we determine the κ reduction induced by different group IV impurities in BAs as a function of concentration and charge state. We unveil a general trend, where neutral impurities scatter phonons more strongly than the charged ones. CB and GeAs impurities show by far the weakest phonon scattering and retain BAs κ values of over ~1000 W⋅K−1⋅m−1 even at high densities. Both Si and Ge achieve large hole concentrations while maintaining high κ. Furthermore, going beyond the doping compensation threshold associated to Fermi level pinning triggers observable changes in the thermal conductivity. This informs design considerations on the doping of BAs, and it also suggests a direct way to determine the onset of compensation doping in experimental samples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

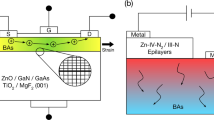

Increased power densities in electronic devices lead to heightened efficiency and durability issues due to overheating, prompting the search for alternative, higher thermal conductivity (κ) materials. Thus, the recently demonstrated high κ of cubic boron arsenide (BAs) offers great promise, particularly for power electronics. Measured values of ~1300 W⋅K−1⋅m−1 have been attained at room temperature for ultra-pure samples1,2,3, in agreement with results from first principles calculations3,4,5. These high values can be explained in terms of a unique collection of properties including high bond stiffness and large mass ratio between As and B atoms, in a way that reduces the scattering phase space for the phonon modes in the material. It has also been predicted that BAs should have simultaneously high room temperature electron and hole mobilities of over 1000 cm2⋅V−1⋅s−1 6. This suggests the possibility that BAs could be used as an effective functional material in next-generation electronic devices, and its much higher thermal conductivity would minimize device failure from hot spot formation. Such a benefit is of particular importance as device sizes are shrinking and the resulting higher generated power densities are becoming an increasingly serious challenge. However, its use as such a functional material requires doping it, which could potentially destroy its advantageously large κ. Defects such as antisites, vacancies and impurities can lower the intrinsically high thermal conductivity of BAs by orders of magnitude, and n- and p-type dopants need to be identified that preferably maintain the highest possible thermal conductivity.

In past works the role played by intrinsic point defects has been highlighted7,8,9, nevertheless at the present date there is no comprehensive study about the effect of external substitution atoms. Recent investigations from first principles have addressed the thermodynamic stability of many neutral and charged dopants in BAs10,11. Among those, the ones in column IV are of great interest due to their position between the columns of B and As in the periodic table. In particular, the high p-dopability of BAs has been recently studied11,12. Photoluminescence and electron paramagnetic resonance experiments have been used11 along with ab initio calculations to point out the possibility that dopants like C and Si, behaving as acceptors, might affect the BAs-conductivity by virtue of their unintentional presence in boron precursor powders and boride based compounds.

Here we show how each dopant in group IV (C, Si, and Ge), in its neutral and charged forms, affects the thermal conductivity of BAs. This unveils a general trend, where neutral impurities reduce the thermal conductivity more strongly than charged ones. We offer an interpretation in terms of the change in orbital occupation between the original and substituted system. We also highlight the initially counter-intuitive fact that, even for substitutions involving a large mass-difference value, the mass-difference scattering can be small. Finally, we show that in BAs excessive doping beyond the Fermi level pinning point activates phonon-donor scattering events, which can either slow down the decrease of thermal conductivity or cause it to plummet, depending on the type of impurity. This should be considered in future applications of BAs. Remarkably, we find that phonon scattering by CB and GeAs impurities is exceptionally weak. As a result, ultrahigh BAs κ values can be achieved even for high CB and GeAs densities. Furthermore, we predict that SiAs and GeAs impurities will be useful p-type dopants with both achieving relatively high free hole densities while maintaining BAs κ values far higher than those in any common semiconductor.

Results

Background and theoretical approach

In insulators and semiconductors, phonons are the major carriers of heat. An applied temperature gradient drives a phonon current. Under steady state conditions, this phonon drift is balanced by resistance from phonon scattering processes. Intrinsic thermal resistance comes from anharmonic phonon-phonon scattering13. In BAs, both lowest-order three-phonon and higher-order four-phonon scattering are required to accurately describe the intrinsic, defect-free thermal conductivity5. Substitutional dopants introduce two types of perturbations: on-site mass perturbations, VM, resulting from the mass difference between the host and substituting atoms, and extended bond perturbations, VK, resulting from the distortion in the local bonding environment produced by the impurity. The total perturbation, V = VM + VK, produces additional phonon scattering that lowers the BAs thermal conductivity. We assume that the dopants are randomly distributed throughout the BAs crystal and that their concentrations are sufficiently low that each defect can be treated as an independent scattering center. To describe phonon thermal transport in BAs in the presence of intrinsic three- and four-phonon scattering and C, Si and Ge dopants, we solve the phonon Boltzmann Transport Equation (BTE)14,15. Phonon-defect scattering is described using a T-matrix approach16,17, which treats the defects to all orders in perturbation theory. The theoretical approach for constructing VM and VK, determining the phonon scattering rates and calculating the BAs thermal conductivity is described in detail in the Methods section.

Phonon transport in BAs is peculiar in the sense that it is dominated by phonons in a narrow window of frequencies between 4 and 8 THz. This is due to several features in BAs including a large frequency gap between acoustic and optic phonons, a narrow optic phonon bandwidth, a bunching together of acoustic phonon branches and exceptionally weak four-phonon scattering. This combination of features gives rise to unusually large contributions to κ from acoustic phonons in this particular range3,4.

Mass defect scattering

Let us first look at the scattering produced by the mass difference between the introduced dopant atom and the host atom (either B or As), conveyed through the perturbation, VM. The absolute mass difference normalized by the host atom mass is 0.1 (0.8) for C substituted for B (As), 1.6 (0.6) for Si substituted for B (As), and 5.7 (0.03) for Ge substituted for B (As). GeAs and CB substitutions correspond to the smallest mass differences, since Ge and As and C and B are adjacent on the periodic table. For the rest of the substitutions the mass difference is large.

In BAs, acoustic phonons carry almost all the heat. Figure 1 shows the calculated scattering rates of acoustic phonons for impurity density of 3.26⋅1018 cm−3 including only the mass defect perturbation VM. In contrast with the case of single-species compounds, the magnitudes of the mass defect scattering rates in Fig. 1 do not follow a monotonic behavior with respect to the normalized mass difference: in binary compounds with a large heavy-to-light mass ratio of the constituent atoms, like BAs, almost all acoustic phonon modes throughout the Brillouin zone involve dominant motion of the heavy (As) atoms, while the light (B) atoms remain relatively stationary. As a result, mass defects placed on the heavy atom sites lead to strong scattering of acoustic phonons while those placed on the light atom site become almost invisible to acoustic phonons and provide only weak scattering18. An approximated analytical expression for the mass-difference scattering rate in large mass-ratio binary compounds was given by Lindsay et al.18, and experimentally verified by Chen et al.19.

Bond defect scattering

The scattering rates for acoustic phonons including only the bond distortions, VK, produced by neutral and charged dopants are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. Singly charged states are assumed so that the number of valence electrons at the impurity site matches the number on the replaced host atom. Organized according to lowest formation energy10,11, these are: \({\,\text{Si}}_{\text{As}\,}^{-1}\), \({\,\text{Ge}}_{\text{As}\,}^{-1}\), \({\,\text{C}}_{\text{As}\,}^{-1}\), \({\,\text{Si}}_{\text{B}\,}^{+1}\), \({\,\text{Ge}}_{\text{B}\,}^{+1}\), \({\,\text{C}}_{\text{B}\,}^{+1}\). The plots reveal a remarkable trend: phonon scattering by neutral defects is generally stronger than that by charged defects. We can possibly attribute this general phenomenon to the fact that the ionized charged states more closely resemble the electronic structure of the original host: when an atom in column IV replaces an As (B) atom, it tends to get charged by accepting (donating) an extra electron, thus becoming iso-electronic with the original atom for which it has substituted. If the impurity remains neutral, however, the extra hole (electron) present at the defect site is responsible for bond perturbations on the crystal structure that do not take place when dealing with ionized states. This hypothesis deserves further investigation in the future. The effect is most noticeable in GeAs, CB and SiAs, as seen in Supplementary Fig. 1. These three impurities also have weaker bond defect scattering than do GeB, SiB and CAs.

To compactly express this finding, it is useful to define and evaluate a descriptor for both charged and neutral impurity states. The descriptor, Ddef;K, sums the phonon-bond defect scattering rates throughout the Brillouin zone which fall in the frequency range of maximum contributions to the defect-free BAs κ:

Here, \({\tau }_{\lambda ;K}^{-1}\) is the phonon-defect scattering rate evaluated by including the VK perturbation only, lambda designates a phonon mode (wave-vector and polarization), N is the number of points in the reciprocal space grid, θ is the Heaviside step-function, and ω1 and ω2 are 4 and 8 THz, respectively. In Eq. (1) we consider an impurity concentration of one defect per unit cell, as using a more dilute value would only scale Ddef;K by a χ factor. The evaluated descriptor is shown in Fig. 2 for dopants in the neutral and charged states. The latter correspond to those with the lowest formation energy10,11: \({\,\text{Si}}_{\text{As}\,}^{-1}\), \({\,\text{Ge}}_{\text{As}\,}^{-1}\), \({\,\text{C}}_{\text{As}\,}^{-1}\), \({\,\text{Si}}_{\text{B}\,}^{+1}\), \({\,\text{Ge}}_{\text{B}\,}^{+1}\) and \({\,\text{C}}_{\text{B}\,}^{+1}\). Figure 2 confirms the findings from the scattering rates calculations.

Descriptor, Ddef;K, which gives an estimate of the strengths of the phonon-bond defect scattering rates in BAs from charged and neutral SiAs, GeAs, CB, CAs, SiB, and GeB dopants in the 4–8 THz range, as defined in Eq. (1).

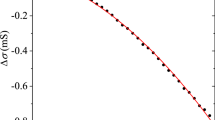

Phonon thermal conductivity

Figure 3 shows plots of the BAs thermal conductivity at room temperature (300 K) as a function of doping concentration for each of the six impurities considered. Solid lines correspond to the neutral impurity cases, while dotted lines are for the charged defects. At low concentrations, all curves merge to the pristine thermal conductivity value of around κ = 1200 W⋅m−1⋅K−1, where only three- and four-phonon scattering occurs3,4,5. With increasing impurity concentration, the behavior of the thermal conductivity clearly reflects the behavior of the phonon-defect scattering rates: at a given dopant density, the reduction of κ is larger for impurities in their neutral states compared with those in their charged states. Colored horizontal arrows in Fig. 3 indicate the differences between charged and neutral impurity concentrations that produce a 50% reduction in the BAs κ. The consistently larger densities achieved for each of the charged impurities compared with their neutral counterparts highlight the weaker scattering of phonons for impurities in their charged states. The CAs and GeB defects suppress the thermal conductivity the most, with a 50% reduction to ~600 W⋅m−1⋅K−1 at a defect concentration of ~1019 cm−3; SiAs closely follows, because its large mass variance dominates over the otherwise weak bond defect scattering. Since Si and C are known contaminants in BAs growth11, the present finding that they strongly reduce the BAs κ motivates synthesis approaches that minimize their presence, if maximum thermal conductivity is desired. Interestingly, SiB does provide quite a large reduction of κ in both the neutral and charged cases despite having relatively weak low frequency mass defect scattering rates, because the scattering induced by the bond perturbation is quite high between 4 and 8 THz, similar to both CAs and GeB. This effect clearly cannot be captured by a pure mass defect perturbation. The opposite holds for GeAs: it gives the smallest reduction to the BAs thermal conductivity for both charged and neutral cases, where phonon-impurity scattering rates are about an order of magnitude smaller than those for the CAs substitution in the critical 4–8 THz range.

Lattice thermal conductivity of BAs vs doping concentration at 300 K for each of the considered impurities. Solid lines: neutral impurities. Dotted lines: charged impurities. Colored arrows indicate the difference between charged and neutral impurity concentrations that produce a 50% reduction in the BAs κ.

In the CAs, GeB and SiAs cases the mass variance hides the effect produced by the structural relaxation and by the change in the local bonds to such degree that the κ differences between neutral and charged states are small, especially in the SiAs case where the bond perturbation is already weak, see Fig. 3. Instead, the effect of VK plays a much more relevant role when the mass variance is weak, that is in the SiB, CB and GeAs cases. In particular, in the latter two it constitutes the largest component of the perturbation and the difference between neutral and charged states is more marked. Moreover, for the SiB substitution, relatively weak rates at low frequency (~<4 THz) in the charged case are compensated by a much stronger perturbation at high frequency.

Effect of compensation

In Fig. 3, each curve corresponds to the reduction of the BAs thermal conductivity assuming that the density of a particular impurity can be varied independently. We now consider a more complex behavior that might occur if the BAs growth process were governed by equilibrium thermodynamics. For low densities of the three dopants D = C, Si, Ge, the calculated formation energies for the charged acceptors, Si\({\,}_{\,\text{As}\,}^{-1}\), Ge\({\,}_{\,\text{As}\,}^{-1}\) and C\({\,}_{\,\text{As}\,}^{-1}\), are much lower than those for charged donors11,12 so these impurities will form first. As the doping density increases and the Fermi level, ϵF, shifts towards the valence band edge, the D-acceptor formation energies increase while D-donor formation energies decrease11,12 thereby increasing the probability of D-donor formation. At the crossing point of the acceptor and donor formation energies, acceptors and donors form with equal probability and ϵF becomes pinned. Thus, equilibrium growth thermodynamics mandates that beyond a certain concentration, adding more D-impurities will form not only D-acceptors but also compensating D-donors. In addition, temperature dependent mixtures of charged and neutral acceptors coexist because of the finite acceptor ionization energy. Therefore, understanding how donor compensation and the differences between neutral and charged defect scattering rates could shape dependence of the BAs thermal conductivity versus impurity concentration should be considered.

In the case of Ge doping, at lower densities Ge\({\,}_{\,\text{As}\,}^{-1}\) defects reduce κ only slightly. But once Ge\({\,}_{\,\text{B}\,}^{+1}\) starts to form, κ decreases more rapidly due to the much larger scattering rates of the latter. The opposite behavior occurs for C doping since C\({\,}_{\,\text{As}\,}^{-1}\) scatters phonons more strongly than C\({\,}_{\,\text{B}\,}^{+1}\). The actual donor concentration depends on the impurity formation energies, on band structure-related quantities and on the experimental growth conditions as well - thus its precise ab initio calculation is challenging. Nevertheless, we employed the formation energy curves and ionization energies calculated from first principles by Chae et al.10, which gave the following Fermi level pinning values (eV) for As-rich (B-rich) conditions: C: 0.4 (0.15), Si: 0.15 (−0.05), Ge: 0.25 (0.0). We used these values along with averaged effective masses \({m}_{\,\text{h}\,}^{* } \sim\) 0.56 and \({m}_{\,\text{e}\,}^{* } \sim\) 0.4 from ref. 11 to estimate the concentrations of charged and neutral acceptors and of compensating donors for each impurity density applying the charge neutrality condition at an assumed growth temperature of 1163 K, consistent with measurements20. By including the scattering rates for charged and neutral acceptors and the compensating donors at the transport temperature of 300 K we have calculated the BAs κ vs. impurity concentration curves in Fig. 4. Solid lines show the Ge-doping and C-doping cases for B-rich and As-rich growth conditions. For comparison, dashed curves in Fig. 4 reproduce the \({\,\text{Ge}}_{\text{As}\,}^{-1}\) and \({\,\text{Ge}}_{\text{As}\,}^{0}\) curves from Fig. 3. Including the effects of compensation hardly changes the curves for Si compared with those already plotted in Fig. 3 so they are omitted from Fig. 4. The change of dependence in the case of Ge doping is particularly evident. When grown in B-rich conditions, BAs could in principle be p-doped with Ge to nearly 1019 cm−3, without much decrease in the thermal conductivity, with somewhat smaller but still high κ values achieved for the As-rich case. Beyond this doping level, the thermal conductivity would decrease more rapidly compared with the Ge\({\,}_{\,\text{As}\,}^{-1}\) - only case, with detrimental consequences for device heating. In contrast to the Ge doping, increased C-doping density leads to the opposite behavior. Since phonon scattering from \({\,\text{C}}_{\text{B}\,}^{+1}\) is very weak compared with that from \({\,\text{C}}_{\text{As}\,}^{-1}\), the C curves including compensation in Fig. 4 lie above the CAs curve that neglects compensation. The difference is particularly noticeable for the case of B-rich growth. We note that As-rich conditions are known to be more favorable for growth, whereas growth of B-rich BAs can be hampered by formation of the subarsenide phase B6As11.

Lattice thermal conductivity of BAs vs Ge and C impurity concentration at 300 K including effects of donor compensation. Results for both As-rich and B-rich conditions are given. Dashed curves \({\,\text{Ge}}_{\text{As}\,}^{-1}\) and \({\,\text{C}}_{\text{As}\,}^{0}\) are taken from Fig. 3 and included for comparison.

Discussion

With increasing Si, Ge and C impurity densities, free hole densities first increase, then saturate and finally decrease due to compensation from electrons ionized from increasingly large concentrations of donor atoms, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Maximum hole densities of 2 × 1018 cm−3, 1 × 1018 cm−3, and 1.5 × 1017 cm−3 are obtained for Si, Ge and C, respectively. The lower value for C results primarily from its larger acceptor ionization of 0.09 eV compared with the corresponding value of 0.03 eV for both Ge and Si, as calculated ab initio10. These results are for impurity formation energies for the As-rich growth conditions expected to apply in current BAs synthesis. Ignoring donor compensation (dashed curves in Supplementary Fig. 2) gives similar results for Si and Ge up to impurity densities of around 1019 cm−3. These finding suggest that there is not much gain in hole density for impurity concentrations much above a few times 1018 cm−3, especially when high thermal conductivity is desired.

For the experimentally achievable As-rich growth, Ge doping shows a clear advantage over C and Si doping as donor compensation starts to be important only at concentrations approaching 1019 cm−3. More broadly, for all three dopants, the BAs κ exceeds 600 W⋅m−1⋅K−1 even at high dopant densities, thus retaining values far above those of common semiconductors such as Si (140 W⋅m−1⋅K−1) and GaAs (45 W⋅m−1⋅K−1). This could be a great advantage in applications where efficient heat dissipation is crucial. Furthermore, the results in Fig. 4 suggest a complementary experimental way to determine if compensation doping is occurring by directly measuring the thermal conductivity. Further calculations and experiments may be envisaged in this way, to evaluate the effect of compensation on the thermal transport properties in semiconductors. Finally, we note that while charged CB substitutions in the absence of CAs would give only minimal reduction of the BAs κ up to high densities, use of C as an n-type dopant would be hindered by the large CB formation and ionization energies10,11.

In conclusion, we have evaluated the thermal conductivity reduction induced by doping BAs with C, Si and Ge. GeAs and CB substitutions give exceptionally small reductions to the BAs thermal conductivity even at high densities. However, the large formation and ionization energies of CB donors hinder their utility as n-type dopants and motivates a search for other candidates. Both Si and Ge achieve reasonably high hole densities while retaining high BAs thermal conductivity. Importantly, even at high impurity densities the BAs κ significantly exceeds those of common semiconductors, highlighting its potential as a next-generation self-cooling functional material. An observable drop (enhancement) in thermal conductivity with respect to the charged D-acceptor case is predicted and explained upon Ge(C)-doping if we consider compensating donor scattering centers and the temperature/doping dependence for the acceptor activation. This imposes practical limitations to be considered when designing BAs - based devices. It also suggests a direct alternative way to experimentally determine if a sample suffers from compensation doping. Finally, we have computationally identified a general phenomenon whereby charged impurities isoelectronic with the substituted species scatter phonons noticeably more weakly than their corresponding neutral counterparts. This phenomenon deserves further investigation in other systems with thermodynamically stable neutral impurities.

Methods

BTE and thermal conductivity

The phonon Boltzmann Tranport Equation (BTE)14,15 is solved for the non-equilibrium phonon distribution function resulting from an applied temperature gradient, ∇T. From this, the thermal conductivity can be obtained, as described below. For small ∇T, the BTE can be linearized and solved self-consistently using the single mode relaxation time approximation (SMRTA) as a starting guess. By keeping only the terms linear in ∇T, for a given mode λ ≡ (q, s) where q is a phonon wave-vector and s is a phonon branch, one can obtain the deviation from equilibrium for its phonon distribution, i.e., \({n}_{\lambda }={n}_{\lambda }^{0}-{\partial }_{T}{n}_{\lambda }^{0}{{\bf{F}}}_{\lambda }\cdot {\bf{\nabla T}}\), where \({{\bf{F}}}_{\lambda }={\tau }_{\lambda }^{0}({{\bf{v}}}_{\lambda }+{{\boldsymbol{\Delta }}}_{\lambda }[{{\bf{F}}}_{\lambda }])\), \({\tau }_{\lambda }^{0}\) is the phonon relaxation time, vλ is the phonon group velocity, \({n}_{\lambda }^{0}\) is the Bose-Einstein distribution and Δ is a linear functional of Fλ. We can interpret Fλ as a vector mean free path that measures the deviation from equilibrium induced by the thermal gradient. Δ ≡ 0 corresponds to the SMRTA. In this work we consider three-, four-, and defect-mediated two-phonon scattering processes15,21, the latter involving either isotopes or substitutional impurities. Here only the three-phonon scattering is included in Δλ while the four-phonon and defect scattering is included at the SMRTA level only with an acceptable level of accuracy, as the former is dominated by Normal processes while the latter involve mostly Umklapp processes5. The phonon thermal conductivity tensor (α, β denote Cartesian directions) is:

where kB is the Boltzmann constant, Ωs is the crystal volume and ωλ is the phonon angular frequency. Due to the cubic symmetry of BAs, the diagonal elements of the tensor are identical, thus it is clearly meaningful to consider only κ = ∑ακαα/3.

Scattering rates and phonon-defect interaction

The total relaxation time \({\tau }_{\lambda }^{0}\) can be computed from the Matthiessen’s rule:

The non-harmonic three- and four-phonon scattering rates are evaluated from first principles by computing the third and fourth-order force constants3,15. We rely on the work of Tamura et al.22 to assess the phonon-isotope interaction, whilst a T-matrix based approach has been developed to treat the substitutional impurities that involve both a mass VM and a bond perturbation VK near the impurity16,17. The total perturbation is thus defined as V = VM + VK, where:

and

here i, j identify atoms in the supercell; Mi (\({\tilde{M}}_{i}\)) is the mass of the host (substitution) atom at site i; and Kij,αβ (\({\tilde{K}}^{ij,\alpha \beta }\)) is the harmonic force constant tensor element between atoms i and j in the pristine (defective) supercell. Once V is known, one can calculate the pristine, retarded Green’s function:

and finally the scattering T-matrix to all orders:

We assume that the defects are randomly distributed throughout the crystal and that their concentration is sufficiently low that each impurity can be treated as an independent scattering center. Since the defect concentrations considered here are dilute, less than around 0.1% of either As or B atoms, effects associated with phonon scattering from multiple defects can be ignored23. At such low concentration we can also ignore any frequency renormalization induced by impurities, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. Thus, the phonon-defect scattering rates can be expressed as:

where χ is the volume concentration of impurities in the system and Vuc is the unit cell volume.

Charged/neutral impurity densities and donor compensation

With increasing impurity density, the magnitude of neutral and charged defects varies. Of particular importance: donor compensation begins to occur after a certain doping level is reached10. To account for this, we combine the effect of the neutral and ionized acceptors and the donors to a single rates expression using Matthiessen’s rule. To estimate the concentrations of charged and neutral impurities and compensating donors formed during growth, we impose the charge neutrality condition, namely

where p, n, \({N}_{\,\text{A}\,}^{-}\) and \({N}_{\,\text{D}\,}^{+}\) are, respectively, the hole, electron, ionized acceptor and ionized donor concentrations. The standard expressions for p and n are:

where Dh(ϵ) and De(ϵ) are the hole and electron Density of States (DOS), ϵVBM and ϵCBM are the Valence Band Maximum and Conduction Band Minimum, ϵF is the Fermi Level and f(ϵ; ϵF, T) is the equilibrium Fermi Dirac distribution. A simple isotropic parabolic band model has been employed to evaluate the hole- and electron- DOS near the gap:

Here, ϵCBM and ϵVBM are the electronic energies at the conduction and valence band edges. Now, given the acceptor and donor electronic levels ϵA and ϵD we consider

and

along with NA + ND = χ, where χ is the total concentration of impurities, and we define g ≡ ND/NA. The value of fD can be safely assumed to be equal to one, since (ϵD − ϵF) ≫ kBT for all the considered doping range. Therefore we have NA = χ/(1 + g) and \({N}_{\,\text{D}}^{+}\simeq {N}_{\text{D}}=g\chi /(1+g)\).

The definition of g is of paramount importance for the determination of the fraction of donors and acceptors. Here we have assumed that impurities are cast into BAs at growth - temperature Tgrowth = 1163 K20 and that diffusion processes are negligible, which results in fixed NA and ND when the temperature is lowered. To do that, we have first solved Eq. (9) by taking g at Tgrowth with \({N}_{\,\text{D}}^{+}/{N}_{\text{A}\,}^{-}=\exp [-({E}_{\text{D}}-{E}_{\text{A}})/({k}_{B}{T}_{\text{growth}})]\), where EA and ED are respectively the formation energies for the charged acceptor and charged donor state10,11. The expression for g stems from the Gibbs free energy for the doped system, where the contribution from vibrational entropy has been neglected. The ensuing and fixed values of NA(Tgrowth) and ND(Tgrowth) have been utilized for each value of χ to evaluate fA at T = 300 K. Finally, if we set \({V}_{\text{uc}}\Im {\langle {T}_{\text{DEF}}^{+}\rangle }_{\lambda }/{\omega }_{\lambda }\equiv {\,\text{B}}_{\lambda }^{\text{DEF}\,}\) for each type and state of defect, we have:

Computational details

We use the VASP24,25,26 DFT code employing the PAW27,28 pseudopotentials in the PBE29,30 approximation for the phonon calculations. First, the second order force constants (IFC2) are calculated for a relaxed 5 × 5 × 5 (250 atom) supercell with and without a substitution defect, using the small displacement method. Phonopy package31,32 is used to create the supercells with small displacements, and to read off force constants following DFT calculations. To calculate VK, we first proceeded by taking the difference between the IFC2s of the pristine and the defective system.

Whereas our procedure is implemented in real space, to reduce the computational workload we consider the local nature of the bond perturbation and we choose two cutoffs, namely rcut and Rcut. One cutoff represents the maximum distance that allows interactions between pairs of atoms, at least one of which belongs to the list of neighbors of the defect site selected by Rcut. After convergence tests we have chosen the pair- and the neighbor list- cutoffs as 0.6–0.8 nm respectively. Once these values are defined, it is necessary to reinforce the acoustic sum rule: this is done by projecting away the degrees of freedom corresponding to rigid translations33. Despite the insulating nature of BAs, we can observe that the character of the state when introducing neutral impurities is metallic. In this case we must use a certain care when evaluating the interatomic forces and force constants: if the VASP smearing parameters were chosen to be as for insulators, this would lead to long range interactions and thus absence of convergence for the phonon-defect scattering rates with respect to the cutoffs. In this work we used the default VASP smearing parameters (ISMEAR = 1, SIGMA = 0.2), comparing with volume-relaxation and spin-relaxation (non-collinear) calculations as well and finding that the latter do not affect rates and thermal conductivity. A converged value for rcut and Rcut was found in all the calculations. To account for the charged impurity states, we raise (As site substitutions) or lower (B site substitutions) the total number of valence electrons for the substituted atom by 1 with respect to the neutral impurity case and then a compensating uniform positive or negative background charge is added to the supercell to maintain charge neutrality.

The scattering T-matrix is then calculated using V = VK + VM and the Green’s function using our home-grown code. Once the T-matrix is known, the phonon-substitution defect scattering rates are calculated for various defect concentrations. These are explicitly shown in Supplementary Figs. 4–9 at the concentration of 3.26⋅1018 cm−3, considering the mass-only, bond-only and total perturbations in both the charged and neutral state and for all the considered impurities. To calculate the three-phonon scattering rates, we use the thirdorder_vasp.py code34 in conjunction with VASP and almaBTE35. The calculation of the four-phonon scattering rates are expensive. Moreover, our home-grown four-phonon code is currently set up to work only with the Quantum Espresso36 suite. We simply interpolate these scattering rate on the wave vector mesh used in the current study from a previously published calculation3. The phonon-substitution defect scattering rates are combined with the three- and four-phonon, and phonon-isotope scattering rates at the relaxation time approximation level using Matthiesen’s rule inside the almaBTE code. almaBTE finds the full solution of the linearized phonon BTE, and outputs the thermal conductivity κ. A converged 28 × 28 × 28 transport wave vector mesh is used to solve the phonon BTE, whilst the Green’s function is evaluated on a 16 × 16 × 16 grid. Values for the Si, C, and Ge acceptor and donor formation energies, EA and ED, acceptor and donor ionization energies, ϵA − ϵVBM, and ϵCBM − ϵD and energy gap have been taken from ref. 10.

Data availability

Four-phonon scattering rates used in the thermal conductivity calculations for BAs and VASP related files are available upon reasonable request. All other data is available from Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4453192.

References

Kang, J. S., Li, M., Wu, H., Nguyen, H. & Hu, Y. Experimental observation of high thermal conductivity in boron arsenide. Science 361, 575–578 (2018).

Li, S. et al. High thermal conductivity in cubic boron arsenide crystals. Science 361, 579–581 (2018).

Tian, F. et al. Unusual high thermal conductivity in boron arsenide bulk crystals. Science 361, 582–585 (2018).

Lindsay, L., Broido, D. A. & Reinecke, T. L. First-principles determination of ultrahigh thermal conductivity of boron arsenide: a competitor for diamond? Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 025901 (2013).

Feng, T., Lindsay, L. & Ruan, X. Four-phonon scattering significantly reduces intrinsic thermal conductivity of solids. Phys. Rev. B 96, 161201 (2017).

Liu, T.-H. et al. Simultaneously high electron and hole mobilities in cubic boron-V compounds: BP, BAs, and BSb. Phys. Rev. B 98, 081203 (2018).

Kim, J. et al. Thermal and thermoelectric transport measurements of an individual boron arsenide microstructure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 201905 (2016).

Lv, B. et al. Experimental study of the proposed super-thermal-conductor: BAs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 074105 (2015).

Zheng, Q. et al. Antisite pairs suppress the thermal conductivity of BAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 105901 (2018).

Chae, S., Mengle, K., Heron, J. T. & Kioupakis, E. Point defects and dopants of boron arsenide from first-principles calculations: donor compensation and doping asymmetry. Appl. Phys. Lett. 113, 212101 (2018).

Lyons, J. L. et al. Impurity-derived p-type conductivity in cubic boron arsenide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 113, 251902 (2018).

Bushick, K., Mengle, K., Sanders, N. & Kioupakis, E. Band structure and carrier effective masses of boron arsenide: effects of quasiparticle and spin-orbit coupling corrections. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 022101 (2019).

Ziman, J. Electrons and phonons: the theory of transport phenomena in solids. International series of monographs on physics (OUP Oxford, 2001).

Omini, M. & Sparavigna, A. Beyond the isotropic-model approximation in the theory of thermal conductivity. Phys. Rev. B 53, 9064–9073 (1996).

Li, W., Carrete, J., Katcho, N. A. & Mingo, N. ShengBTE: a solver of the Boltzmann transport equation for phonons. Comp. Phys. Commun. 185, 1747–1758 (2014).

Mingo, N., Esfarjani, K., Broido, D. A. & Stewart, D. A. Cluster scattering effects on phonon conduction in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 81, 045408 (2010).

Economou, E. N. Green’s functions in quantum physics (Springer, 2006). URL https://books.google.fr/books?id=s0gsAAAAYAAJ.

Lindsay, L., Broido, D. A. & Reinecke, T. L. Phonon-isotope scattering and thermal conductivity in materials with a large isotope effect: a first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 88, 144306 (2013).

Chen, K. et al. Ultrahigh thermal conductivity in isotope-enriched cubic boron nitride. Science 367, 555–559 (2020).

Tian, F. et al. Seeded growth of boron arsenide single crystals with high thermal conductivity. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 031903 (2018).

Feng, T. & Ruan, X. Quantum mechanical prediction of four-phonon scattering rates and reduced thermal conductivity of solids. Phys. Rev. B 93, 045202 (2016).

Tamura, S.-i Isotope scattering of large-wave-vector phonons in GaAs and InSb: deformation-dipole and overlap-shell models. Phys. Rev. B 30, 849–854 (1984).

Walton, D. Phonon-defect interaction. (Springer US: Boston, MA, 1975) 393–440.

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Burke, K., Perdew, J. P. & Ernzerhof, M. Why semilocal functionals work: accuracy of the on-top pair density and importance of system averaging. J. Chem. Phys. 109, 3760–3771 (1998).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 108, 1–5 (2015).

Togo, A., Oba, F. & Tanaka, I. First-principles calculations of the ferroelastic transition between rutile-type and CaCl2-type SiO2 at high pressures. Phys. Rev. B 78, 134106–134114 (2008).

Katre, A., Carrete, J., Dongre, B., Madsen, G. K. H. & Mingo, N. Exceptionally strong phonon scattering by B substitution in cubic SiC. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 075902 (2017).

Li, W., Lindsay, L., Broido, D. A., Stewart, D. A. & Mingo, N. Thermal conductivity of bulk and nanowire Mg2SixSn1−x alloys from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 86, 174307 (2012).

Carrete, J. et al. almaBTE: a solver of the space-time dependent Boltzmann transport equation for phonons in structured materials. Comput. Phys. Commun. 220, 351–362 (2017).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Office of Naval Research under MURI grant no. N00014-16-1-2436, and the Agence Nationale de la Recherche through project ANR-17-CE08-0044-01. G.K.H.M. acknowledges funding from the Austrian Science Funds (FWF) under project CODIS (Grant no. FWF-I-3576-N36). We thank Nebil Katcho for providing us with the first version of the code used to compute the phonon-defect scattering rates. D.B. thanks Dr. John Lyons of the Naval Research Laboratory for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.F. and N.H.P. contributed equally. M.F., N.H.P. and C.L. performed the first-principles calculations. M.F., N.H.P. N.M. and D.B. wrote the manuscript and developed the analytical modeling. N.M. and D.B. supervised the research. All authors analyzed the data and commented on, discussed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fava, M., Protik, N.H., Li, C. et al. How dopants limit the ultrahigh thermal conductivity of boron arsenide: a first principles study. npj Comput Mater 7, 54 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-021-00519-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-021-00519-3

This article is cited by

-

Lattice Thermal Transport of BAs, CdSe, CdTe, and GaAs: A First Principles Study

Journal of Electronic Materials (2023)

-

The elphbolt ab initio solver for the coupled electron-phonon Boltzmann transport equations

npj Computational Materials (2022)