Abstract

Topotactic phase transition between metallic, perovskite SrFeO3 and insulating, Brownmillerite SrFeO2.5 has been extensively studied due to the potential applications in resistive switching devices for neuromorphic computing. However, its practical utilization as memristors has been hindered by the structural instability of SrFeO3, which is often ascribed to the generation of oxygen vacancies to form SrFeO3-δ. Here we reveal that the dominating defects generated in SrFeO3 epitaxial thin films are atomic scale gaps generated as a result of interfacial strain. Our correlated time- and strain-dependent measurements show that tensile strained SrFeO3 films form vertical, nanoscale gaps that are SrO-rich, which are accountable for the observed metal-to-insulator transition over time. On the other hand, compressively strained or small lattice mismatched SrFeO3 films mainly yield horizontal gaps with a smaller impact on the in-plane transport. The atomic scale origin of such defects and their impact on device performance need to be further understood in order to integrate phase change materials in oxide electronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perovskite-structured strontium ferrite SrFeO3, together with its sub stoichiometric oxides SrFeO3-δ (SFO), have attracted great attention due to their rich structural, physical, and chemical properties1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. In particular, as illustrated in Fig. 1a, the reversible topotactic phase transition occurring between SrFeO3 and the reduced Brownmillerite-structured SrFeO2.5 has been shown to induce resistive switching phenomena9,11,12,13. Moreover, Ge et al.7 clearly demonstrated that the reversible phase transition between brownmillerite and perovskite phases can be realized through gating-controlled insertion and extraction of oxygen ions in SFO films, which may allow the use of such materials in high-performance artificial synapses for neuromorphic computing. While epitaxial growth of SFO in thin film form offers a scalable way to integrate them in oxide electronics, there are still several challenges hindering their practical applications. For example, bulk SrFeO3 can be readily synthesized through high-pressure and high-temperature techniques, but SFO thin films grown by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) or pulsed laser deposition (PLD) have been shown to contain significant amount of oxygen vacancies (VOs) due to the low oxygen partial pressure employed7,12,14,15. Recently, it has been shown that the use of more oxidizing agent (e.g., oxygen plasma or ozone) during the synthesis and subsequent processing can lead to fully oxidized SrFeO315,16,17. However, the long-term stability of stoichiometric, metallic SrFeO3 films were found to be not reliable, which has been tentatively ascribed to the instability of Fe4+16,17,18. The exact mechanism remains unclear due to the lack of time-dependent structural and chemical characterization at the atomic scale. Given that the realization of resistive-switching-based oxide electronics depend critically on the materials’ stability, the origin for such structural evolution and conductivity decay needs to be further understood.

a Schematic diagrams of the reversible structure change between BM SrFeO2.5 and perovskite SrFeO3 through oxidation and reduction. The crystal structures were viewed along the [100] direction. b X-ray diffraction (XRD) θ–2θ scans of epitaxial SrFeO3-δ (SFO) thin films on STO substrates. Dotted line indicates the diffraction peaks from STO substrates. As grown, air anneal (ann) and plasma ann denote three different states of SFO films. c DSMs of SFO thin films with three different states around the (103) Bragg reflection of the STO substrates, indicating SFO thin films without any lattice relaxation. d Resistivity (ρ) vs. temperature on heating for SFO thin films with three different states.

In this study, we investigate the time- and strain-dependent atomic and electronic structural evolutions in a set of well-defined SFO films with discrete strain conditions. We show that as a result of interfacial strain, atomic-scale defect planes to nanoscale defect gaps can develop in stoichiometric SrFeO3 films after the oxidation process. While majority of the films remain metallic SrFeO3, the highly localized defect gaps are found to be SrO-rich, and thus can dominate the transport behavior. While a tensile strain generally favors the generation of gaps vertical to the substrate, a compressive strain or small lattice mismatch can yield defect gaps parallel to the substrate. As a result, films under tensile strain display much quicker conductivity decay compared to compressively strained SFO films. The physical origins of such nanoscale defects and their impact on device integration need to be further studied in order to use strontium ferrite and similar phase change materials in future oxide electronics.

Results

Brownmillerite-perovskite phase transition

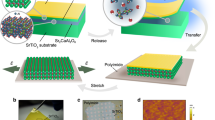

Differently strained perovskite SrFeO3 films used in this study were obtained by annealing PLD-grown SrFeO2.5 films in oxygen plasma (see “Methods”). Figure 1b shows representative X-ray diffraction (XRD) θ–2θ patterns of the as-grown (BM SrFeO2.5), air-annealed (SrFeO3-δ), and plasma-annealed (SrFeO3) thin films on (001)-oriented SrTiO3 (STO) substrates with a 25 nm thickness, respectively. The distinct thickness fringes around Bragg peaks suggest good crystalline quality for all three cases. Compared with the as-grown sample, the SFO diffraction peaks of the air annealed and plasma-annealed samples shift to higher angles, indicating the reduction in out-of-plane (c-axis) lattice parameters. The decrease in the c-axis lattice parameter from 4.008 to 3.855 Å for the air-annealed sample indicates that significant amount of oxygen vacancies in the BM-SFO’s tetrahedral sub-lattices are healed. However, the air annealed SFO film still shows a semiconductor behavior (Fig. 1d), suggesting that it is not fully stoichiometric. In contrast, the SFO film resulting from plasma annealing shows a further reduction in c-axis lattice parameter (3.832 Å) and metallic conductivity (Fig. 1d). The resistivity of the plasma annealed perovskite SrFeO3 film at room temperature is about 1 mΩ cm, consistent with previous reports1,16,19. The measured c-axis lattice parameter is smaller than that of bulk SrFeO3 (3.850 Å)1, as a result of the in-plane tensile strain applied by the STO. X-ray direct space mappings (DSM) near the (103) reflection of STO (Fig. 1c) reveal that all three films are coherently strained to the STO substrates without lattice relaxation.

Conductivity decay over time

For the plasma annealed SFO film grown on STO, we tracked its long-term in-plane transport properties as a function of time. Figure 2a shows the evolution of resistivity versus temperature relationships. A threefold decrease in room-temperature conductivity is observed just one day after plasma annealing. In addition, the in-plane transport behavior of the film became semiconducting and the overall resistivity increases continuously with time. Hong et al.16 reported that the increase in resistivity of the SFO thin film was related to the c-axis expansion and argued that it was presumably due to the creation of oxygen vacancies. Acting as electron donors, oxygen vacancies could reduce Fe4+ to Fe3+ and increase the ionic radius of the Fe ion. The more Fe3+ in SFO, the higher the resistivity and the bandgap3,6,15. In order to evaluate whether oxygen vacancy formation is the leading cause in the observed resistivity change, we also performed time-dependent XRD and spectroscopic ellipsometry (SE) measurements. Figure 2b shows the XRD patterns around the (002) diffraction peak over time. It is clear that albeit the continuous change in resistivity, the change in SFO (002) diffraction peaks is almost negligible with a tiny shift to the smaller angle (the c-axis lattice parameter changing from 3.832 Å (initial) to 3.834 Å (32 days)). DSM scans with time (Supplementary Fig. 1) show that the SFO film is still fully strained to the STO substrate after exposure in air for 32 days. As the c-axis lattice parameter of SFO is very sensitive to the oxygen vacancies (see discussion in Fig. 1), the small change (<0.1%) in c-axis lattice parameter indicates that SFO retains the perovskite phase, where Fe in SFO is mostly in the nominal state of Fe4+ after exposure in air for 32 days. Moreover, the optical absorption spectra derived from SE (Fig. 2c) show no obvious difference over time. According to the previous reports17,20, the absorption feature B is associated with the split-off empty Fe 3d eg/O 2p hybridized band resulting from Fe4+. As shown in Fig. 2c, the feature B does not show obvious change with time, suggesting that the Fe valence is mostly Fe4+, consistent with XRD results. The onset of optical transition B determined by Tauc plots (Supplementary Fig. 2) still shows 0 eV after storing the sample in air for more than one month, indicating the film should retain its metallic behavior. Combined measurements based on ensemble-averaged techniques all suggest that there is little to no detectable changes in materials’ structure, therefore oxygen vacancies should not be the main cause for the observed changes in resistivity.

a ρ vs. temperature on heating, b XRD curves around the (002) diffraction peak, and c absorption spectra measured after plasma annealing (initial), after different days of exposure in air. The black and red dashed lines in (b) indicate the peak positions of the STO substrate and the initial state of plasma annealed SFO film, respectively. The blue dashed line in (b) denotes one thickness fringe. Characteristic features in the low-energy portion of the absorption spectra in (c) are defined as A and B.

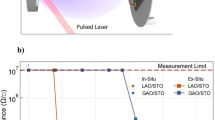

Strain effect

Note that this unstable metallic phase of perovskite SrFeO3 is not limited to the films grown on STO substrates, as conductivity decays with different magnitudes have also been observed in plasma annealed SFO films on various substrates with different strain states (see Fig. 3). In bulk, SrFeO3 is a cubic structure with a lattice constant of 3.850 Å. Hence, SrFeO3 experiences compressive strain of −1.58% on LaAlO3 (LAO), and tensile strains of +0.46%, +1.41%, and +2.53% on (LaAlO3)0.3(Sr2AlTaO6)0.7 (LSAT), STO and DyScO3 (DSO) (Fig. 3a), respectively. As shown in Fig. 3b, after plasma annealing (initial), SFO films on LAO, LSAT and STO display comparable metallic behaviors, in good agreement with the 0 eV bandgap derived from the SE data (Supplementary Fig. 3). However, the initial state of the plasma annealed SFO film on DSO is too resistive to measure based on our current experimental setup, although it also shows a perovskite phase (Supplementary Fig. 4) with near zero bandgap (Supplementary Fig. 3). After exposed in air for 5 days, SFO on LSAT still shows the metallic behavior with a slight increase in resistivity across temperature range. On the other hand, SFO films on LAO and STO show the insulator behavior with one and four orders of magnitude changes in resistivity, respectively. Figure 3c plots time-dependent resistivity changes measured at room temperature for films grown on these four substrates. It is clear that SFO on lattice matched LSAT undergoes the least change. For all other three cases (except SFO on DSO, which is too resistive to measure), the rate of conductivity decay is found to be faster during the first several days until a seemingly plateau is reached. For the compressively strained SFO on LAO, the resistivity increased over an order of magnitude, while the tensile strained SFO on STO showed an increase over four orders of magnitude. Such a strong strain dependence indicates atomic scale defects, such as misfit dislocations, which are known to impact the in-plane transport properties21,22. To determine the atomistic mechanism for the structural and electronic structure evolutions of SrFeO3 on different substrates, we performed high-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) analysis for these plasma annealed SFO films within a few days after plasma annealing. Figure 3d–g show the cross-sectional high-angle annular-dark-field STEM (HAADF-STEM) images for different samples taken along [100] direction. The prevalent, alternating contrast with double periodicity of the perovskite structure shown in the films is due to the formation of Brownmillerite structures, which could be induced by using focused ion beam during the TEM sample preparation process. The electron beam during STEM imaging may also induce perovskite-Brownmillerite phase transition15. Compared with the as-grown BM-SFO, the striking difference displayed by plasma-annealed samples here is the much higher contrast lines, either parallel (LAO and LSAT) or perpendicular (STO and DSO) to the substrates. These lines correspond to defect planes (gaps) along the beam projection direction. For SFO on DSO, the defect gaps are ~2 nm in width which allowed the surface Au coatings deposited during TEM sample preparation to permeate. Such large-scale defect gaps can greatly impact the in-plane transport and explain why SFO on DSO was too resistive to measure. Comparing the other three STEM images with the time-dependent resistivity evolution shown in Fig. 3c, we can further analyze how the atomic-scale gaps impact conductivity.

a Lattice mismatch (ε) between the bulk P SrFeO3 and the substrates used in this study. Pseudo-cubic lattice constants were used for noncubic substrates. b ρ vs. temperature curves for SFO films grown on different substrates measured after plasma anneal (initial) and 5 days exposure in air. c Room temperature ρ vs. time exposed in air for plasma annealed SFO films grown on different substrates. The stars represent the samples on which X-ray absorption spectra (XAS) were acquired. d–g Cross-sectional HAADF-STEM images of the plasma annealed SFO films grown on (d) LAO, (e) LSAT, (f) STO and (g) DSO. The scale bar is 5 nm. The arrows in (g) denote the Au particles which diffused into the vertical gaps during Au top electrodes’ deposition by sputtering. h, i XAS measured by total electron yield (TEY) detection mode across Fe L edge (h) and O K edge (i). Black, red and blue (dashed blue) denote the BM SrFeO2.5 on STO, the P SrFeO3 on LSAT with 2 days exposed in air, and the P SrFeO3 on STO with 10 (25) days exposed in air, respectively.

In order to probe the structural and chemical changes in the gap region, we performed high-resolution electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) analysis on the SFO/LAO sample (as shown in Fig. 4a). The elemental mappings reveal that the gap regions are Fe and O deficient with local Sr rich. Sr segregation in perovskite oxides is a known problem to deteriorate oxygen reduction kinetics and suppress the oxygen evolution reaction (OER)23,24,25,26, and Sr leaching has been observed after the acidic OER process24,26. In principle, Sr segregation layer is more likely to be in the form of SrO27. Moreover, the gap regions are typically amorphous, but prolonged electron beam irradiation under STEM imaging conditions can promote crystallization and form nanocrystalline SrO (Supplementary Fig. 5). Because SrO is a wide bandgap insulator, the existence of the vertical SrO rich gaps can be considered as local resistors in serial connection in an in-plane transport setup, as illustrated in Fig. 4d, contributing the overall semiconducting behavior albeit the SFO islands are metallic. With humidity exposure, SrO is easy soluble in water and thus should strongly impact the in-plane transport properties (see the model plotted in Fig. 4d). The defect gaps formed in SFO on STO (ε = +1.41%) are vertical to the substrate and can be explained why the conductivity of SFO/STO decays faster. As for SFO on LSAT (ε = +0.46%), the dominating defect gaps are oriented parallel to the substrate, which may adversely affect the vertical transport properties, but has less impact on the in-plane transport, which can explain why the conductivity of this sample decays the slowest. For SFO on LAO (ε = −1.58%), in addition to horizontal gaps, there are some vertical gaps near the surface region. However, the vertical gaps do not penetrate throughout the film, which leaves pathways for electrical conduction, rendering a slower decay compared to SFO/STO. We further investigated water-induced changes in structural stability and transport properties of a plasma-annealed SFO/LAO. DI water soaking (see the inset of Fig. 4b) should lead to large change in resistivity as the excess SrO is water soluble. Indeed, we show that a quick, 5 s DI water exposure leads to two orders of magnitude increase in the resistivity (Fig. 4b), with an accompanied metal-to-insulator transition without color change (see the inset of Fig. 4b). Four orders of magnitude change is observed when the water soaking time is increased to 60 s. Significant structural changes are also observed at the vicinity of the gap regions after soaking as shown in the STEM image (Fig. 4c).

a EELS maps for the vertical gap area of one plasma annealed SFO on LAO. The scale bar is 2 nm. b Resistivity change with DI water soaking. The inset shows the water soaking setup. c Cross-sectional HAADF-STEM image captured after DI water soaking. The scale bar is 5 nm. d Schematic of the main cause for the conductivity decay.

In addition, we also checked X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) across Fe L edge (Fig. 3h) and O K edge (Fig. 3i) for the following samples: as grown BM SrFeO2.5 on STO (SrFeO2.5), plasma annealed SFO on LSAT with 2 days exposure in air (LSAT 2 days), and plasma annealed SFO on STO with 10 days and 25 days exposure in air (STO 10 days and STO 25 days). The Fe L3 spectrum of SrFeO2.5 exhibits a strong peak at ~702.8 eV (indicated by the dashed line) with another pronounced peak at ~701.6 eV (marked by the arrow), consistent with Fe3+ observed in other rare-earth ferrites, such as LaFeO3 and EuFeO328,29. After plasma treatment, the intensity of the peak at around 701.6 eV decreases and there is a clear, ~0.2 eV shift of the major peak to higher photon energy, indicating that plasma treatment leads the transition from Fe3+ to Fe4+ 3. In addition, the FWHM of Fe L-edge XAS spectra becomes larger for the plasma treated samples. O K edge absorption spectra (Fig. 3i) further confirms the transition from Fe3+ to Fe4+ through the pre-edge Fe-O hybridization features. For SrFeO2.5, the pre-edge structure from 528 to 533 eV is very similar to that of the brownmillerite SrFeO2.46 reported by Galakhov et al.3. A strong pre-peak feature is observed for the other three measurements with plasma treatment (marked by blue arrow), which is attributed to the Fe3+→Fe4+ transition3,7,9,17,28. While the spectra difference between LSAT 2 days and STO 10 days are subtle, the difference between STO 10 days and STO 25 days are more evident. As shown in Fig. 3h, the Fe L spectra becomes slightly narrower after aging for 25 days, indicating a partial reduction from Fe4+ to Fe3+, presumably occurring at the vicinity of gap regions close to the surface. The reduction in the intensity of the O K edge pre-peak also corroborate with this assignment, suggesting that oxygen vacancies are created but are localized to the gap regions, which are insensitive to XRD and optical ellipsometry. Therefore, we can conclude that the vertical gaps formation and evolution during and after plasma treatment, and their further interaction with the environment should be the main driving force leading to the decay of metallicity in SFO.

Discussion

The facts that the initial state being metallic right after plasma annealing and no obvious difference in the conductivity of SFO films with various strain states (see Fig. 3b) indicate that the defect gaps or planes most probably develop after oxygen plasma treatment. Without more oxidizing agent (oxygen plasma), oxygen vacancies may develop due to the small formation energy barrier in SrFeO330, which can release the strain effect from substrates, leading to the formation of atomic-scale gaps. Tensile strain could easily form the defects along the vertical direction, and the formed atomic-scale defects (Sr segregation) can quickly propagate and lead to vertical gaps we observed in Fig. 3. By contrast, compressive strain would form the horizontal defect planes.

Based on the above discussion, we can understand that the vertical gaps with SrO-rich in tensile strained SFO lead to a faster conductivity decay and metal-to-insulator transition. Moreover, we did re-oxidation on these plasma annealed samples after multiple days (>1 week) exposure in air. In-plane transport measurements show a good recovery in the SFO/LSAT sample, but the SFO/STO sample displays an irreversible process. As seen in Supplementary Fig. 6, after re-oxidation both SFO/LSAT and SFO/LAO samples display metallic behavior at room temperature while insulating behavior is observed in the SFO/STO sample. However, the retaining of good conductivity in SFO/LSAT may not indicate they are better suited for resistive switching applications, which require vertical integration. As shown in Fig. 3d and e, the horizontal defect gaps may severely impact the electron transport and oxygen diffusion along the film growth direction, which is required to promote the BM-P phase transitions during resistive switching. On the other hand, the existence of SrO-rich vertical gaps may not interfere with the nanoscale resistive switching phenomena, as the gap-separated SFO islands remain coherent to the substrates (Supplementary Fig. 1). Our further experiments will address how the resistive switching properties are impacted by different types of such defect gaps by investigating SFO films grown on differently strained substrate, but with an SrRuO3 thin film as a conductive buffer layer to form the heterojunction devices. Moreover, freestanding SFO films can release the strain effect31,32,33, which may prevent these defect gaps formation after plasma treatment.

To summarize, our time- and strain-dependent studies involving XRD, SE, XPS, STEM, and XAS demonstrate that perovskite SrFeO3 films can undergo significant changes in their structural and electronic properties. However, the dominating defect is highly localized, nanoscale gaps instead of oxygen vacancies resulting from a topotactic phase transition. The SrO-rich defect gaps lead to the observed metal-to-insulator transition and an increase in resistivity. Our study highlights that long-term structural stability of phase change materials need to be addressed in order to harness their novel structural and electronic properties.

Methods

Thin films growth

High-quality epitaxial SrFeO3-δ (0 < δ ≤ 0.5) thin films were grown on a set of single-crystalline substrates, including LAO, LSAT, STO and DSO, by using PLD. Samples were grown at 700 °C in oxygen partial pressure of 0.1 mTorr. After growth, the samples were cooled down to room temperature at the same oxygen partial pressure. For the as-grown BM-SFO film on STO, the ordered oxygen vacancy channels are vertical to the thin film surface, which is determined by our growth parameters and consistent with previous reports7,14,15.

Oxidation treatment

In order to obtain fully oxidized SrFeO3 films, the as-grown SrFeO3-δ films were treated by air anneal and oxygen plasma anneal, respectively. For air anneal, the samples were transferred into a tube furnace and heated to 650 °C in ambient air for 5 h and then cooled down to room temperature with 10 °C/min. For oxygen plasma anneal, the samples were transferred into a UHV chamber and heated to 600 °C in oxygen plasma at a chamber pressure of ~3 × 10−5 Torr for one hour and then cooled down to room temperature slowly. The specific oxygen plasma annealing treatment steps have been described in Ref. 17.

Structural characterization

XRD measurements were performed using a Rigaku SmartLab instrument with Cu Kα1 radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). The high-angle annular-dark-field (HAADF) micrographs of the films were obtained using an ARM200F (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) STEM operated at 200 kV with a CEOS Cs corrector (CEOS GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) to cope with the probe-forming objective spherical aberration. HAADF images were acquired at acceptance semi-angles of 90–370 mrad with a probe current of ~20 pA. The attainable resolution in HAADF images is better than 0.078 nm.

Electronic, optical, and electrical characterization

XAS were carried out at Advanced Light Source (ALS) Beamline 8.0.1, located at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (LBNL). All the spectra were normalized to the beam flux measured by the upstream gold mesh. The resolution of the excitation energy is 0.15 eV without considering core-hole lifetime broadening. Detailed procedures have been introduced in ref. 34. Spectroscopic ellipsometry measurements and electrical resistivity measurements of SFO films have been described in ref. 17.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from authors upon reasonable request.

References

MacChesney, J., Sherwood, R. & Potter, J. Electric and magnetic properties of the strontium ferrates. J. Chem. Phys. 43, 1907–1913 (1965).

Takeda, T., Yamaguchi, Y. & Watanabe, H. Magnetic structure of SrFeO3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 33, 967–969 (1972).

Galakhov, V. et al. Valence band structure and X-ray spectra of oxygen-deficient ferrites SrFeOx. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 5154–5159 (2010).

Yagi, S. et al. Covalency-reinforced oxygen evolution reaction catalyst. Nat. Commun. 6, 8249 (2015).

Hirai, K. et al. Melting of oxygen vacancy order at oxide–heterostructure interface. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 30143–30148 (2017).

Khare, A. et al. Topotactic metal–insulator transition in epitaxial SrFeOx thin films. Adv. Mater. 29, 1606566 (2017).

Ge, C. et al. A ferrite synaptic transistor with topotactic transformation. Adv. Mater. 31, 1900379 (2019).

Kang, K. T. et al. A room‐temperature ferroelectric ferromagnet in a 1D tetrahedral chain network. Adv. Mater. 31, 1808104 (2019).

Nallagatla, V. R. et al. Topotactic phase transition driving memristive behavior. Adv. Mater. 31, 1903391 (2019).

Nemudry, A., Weiss, M., Gainutdinov, I., Boldyrev, V. & Schöllhorn, R. Room temperature electrochemical redox reactions of the defect perovskite SrFeO2.5+x. Chem. Mater. 10, 2403–2411 (1998).

Acharya, S. K. et al. Epitaxial brownmillerite oxide thin films for reliable switching memory. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 7902–7911 (2016).

Saleem, M. S. et al. Electric field control of phase transition and tunable resistive switching in SrFeO2.5. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 6581–6588 (2019).

Tian, J. et al. Nanoscale topotactic phase transformation in SrFeOx epitaxial thin films for high‐density resistive switching memory. Adv. Mater. 31, 1903679 (2019).

Khare, A. et al. Directing oxygen vacancy channels in SrFeO2.5 epitaxial thin films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 4831–4837 (2018).

Wang, L., Yang, Z., Bowden, M. E. & Du, Y. Brownmillerite phase formation and evolution in epitaxial strontium ferrite heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 231602 (2019).

Hong, D., Liu, C., Pearson, J. & Bhattacharya, A. Epitaxial growth of high quality SrFeO3 films on (001) oriented (LaAlO3)0.3(Sr2TaAlO6)0.7. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 232408 (2017).

Wang, L. et al. Hole-induced electronic and optical transitions in La1–xSrxFeO3 epitaxial thin films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 025401 (2019).

Enriquez, E. et al. Oxygen vacancy-driven evolution of structural and electrical properties in SrFeO3−δ thin films and a method of stabilization. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 141906 (2016).

Yamada, H., Kawasaki, M. & Tokura, Y. Epitaxial growth and valence control of strained perovskite SrFeO3 films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 622–624 (2002).

Smolin, S. Y. et al. Static and dynamic optical properties of La1–xSrxFeO3−δ: the effects of A-site and oxygen stoichiometry. Chem. Mater. 28, 97–105 (2015).

Du, Y. et al. Layer-resolved band bending at the n−SrTiO3 (001)/p−Ge (001). interface Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 094602 (2018).

Yun, H. et al. Uncovering the microstructure of BaSnCb thin films deposited on different substrates using TEM. Microsc. Microanal. 24, 2198–2199 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. Impact of Sr segregation on the electronic structure and oxygen reduction activity of SrTi1−xFexO3 surfaces. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 7979–7988 (2012).

Seitz, L. C. et al. A highly active and stable IrOx/SrIrO3 catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. Science 353, 1011–1014 (2016).

Tsvetkov, N., Lu, Q., Sun, L., Crumlin, E. J. & Yildiz, B. Improved chemical and electrochemical stability of perovskite oxides with less reducible cations at the surface. Nat. Mater. 15, 1010 (2016).

Han, B. et al. Iron-based perovskites for catalyzing oxygen evolution reaction. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 8445–8454 (2018).

Koo, B. et al. Sr segregation in perovskite oxides: why it happens and how it exists. Joule 2, 1476–1499 (2018).

Abbate, M. et al. Controlled-valence properties of La1−xSrxFeO3 and La1−xSrxMnO3 studied by soft-x-ray absorption spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 46, 4511 (1992).

Choquette, A. K. et al. Synthesis, structure, and spectroscopy of epitaxial EuFeO3 thin films. Cryst. Growth Des. 15, 1105–1111 (2015).

Das, T., Nicholas, J. D. & Qi, Y. Long-range charge transfer and oxygen vacancy interactions in strontium ferrite. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 4493–4506 (2017).

Lu, D. et al. Synthesis of freestanding single-crystal perovskite films and heterostructures by etching of sacrificial water-soluble layers. Nat. Mater. 15, 1255 (2016).

Hong, S. S. et al. Two-dimensional limit of crystalline order in perovskite membrane films. Sci. Adv. 3, eaao5173 (2017).

Ji, D. et al. Freestanding crystalline oxide perovskites down to the monolayer limit. Nature 570, 87 (2019).

Wu, J. et al. Elemental-sensitive detection of the chemistry in batteries through soft x-ray absorption spectroscopy and resonant inelastic x-ray scattering. J. Vis. Exp. 134, e57415 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The work is support by an LDRD project within Chemical Dynamics Initiative at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL). PNNL is a multi-program national laboratory operated for DOE by Battelle. Initial samples growth was supported by U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Early Career Research Program under Award No. 68278. J.W. would like to thank the financial support of the ALS postdoctoral fellowship. A portion of the work was performed at the W.R. Wiley Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a DOE User Facility sponsored by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research. Soft X-ray spectroscopy data was performed at ALS of LBNL, which is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. We thank Drs. Scott A. Chambers, Tiffany Kaspar, Endong Jia, and Jinhui Tao for valuable discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W., Z.Y., and Y.D. conceived this project. L.W. performed the epitaxial thin film synthesis, plasma processing, and ellipsometry spectroscopy measurements. L.W. and A.Q. performed in-plane electrical transport measurements and data analysis. M.E.B. performed XRD measurements and analysis. Z.Y. performed STEM/EELS measurements and data analysis. J.W. and W.Y. collected and analyzed the XAS data. L.W., Z.Y. and Y.D. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Yang, Z., Wu, J. et al. Time- and strain-dependent nanoscale structural degradation in phase change epitaxial strontium ferrite films. npj Mater Degrad 4, 16 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-020-0120-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-020-0120-3

This article is cited by

-

Understanding the Behavior of Oxygen Vacancies in an SrFeOx/Nb:SrTiO3 Memristor

Electronic Materials Letters (2022)