Abstract

Rydberg atoms, with their enormous electronic orbitals, exhibit dipole–dipole interactions reaching the gigahertz range at a distance of a micrometre, making them a prominent contender for realizing ultrafast quantum operations. However, such strong interactions between two single atoms have so far never been harnessed due to the stringent requirements on the fluctuation of the atom positions and the necessary excitation strength. Here we introduce novel techniques to explore this regime. First, we trap and cool atoms to the motional quantum ground state of holographic optical tweezers, which allows control of the inter-atomic distance down to 1.5 μm with a quantum-limited precision of 30 nm. We then use ultrashort laser pulses to excite a pair of these nearby atoms to a Rydberg state simultaneously, far beyond the Rydberg blockade regime, and perform Ramsey interferometry with attosecond precision. This allows us to induce and track an ultrafast interaction-driven energy exchange completed on nanosecond timescales—two orders of magnitude faster than in any other Rydberg experiments in the tweezers platform so far. This ultrafast coherent dynamics gives rise to a conditional phase, which is the key resource for a quantum gate, opening the path for quantum simulation and computation operating at the speed limit set by dipole–dipole interactions with this ultrafast Rydberg platform.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Progress in the field of quantum simulation and computation is fuelled by efforts made on a variety of platforms (for example, superconducting (SC) qubits, quantum dots, trapped ions, neutral atoms and so on) to reach a critical fidelity of quantum operations. This requires operation on these systems to be orders of magnitude faster than the timescale set by the coupling to the environment; thus, there are continuous attempts to better insulate qubits1,2,3,4,5 and design faster quantum operations6,7,8,9. Among the latter, a critical operation is the entanglement of two qubits, which requires a time lower-bounded by a speed limit tJ = π/J, set by a platform-dependent interaction strength J, which is, for example, proportional to a capacitance between two superconducting qubits10. Although gates were often first realized in an adiabatic regime t ≫ tJ (refs. 11,12,13,14) to minimize couplings with unwanted states or degrees of freedom (DOF) giving unitary errors, entanglement protocols saturating the bound while dealing with these parasitic couplings are highly sought after as they minimize decoherence (non-unitary errors). Devising and realizing such protocols are the subject of intense efforts on all platforms10,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23.

Arrays of Rydberg atoms in optical tweezers are one of the most exciting systems for quantum simulation24,25,26,27 and computation28,29,30,31,32. At its core, the dipole–dipole interaction \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{dip}}}}} \approx {\hat{d}}_{1}{\hat{d}}_{2}/4\uppi {\epsilon }_{0}{R}^{3}\) (refs. 33,34, \({\epsilon }_{0}\) is the vacuum permittivity) is used to operate entanglement between two neutral atoms separated by a microscopic distance R owing to the large matrix elements of the dipole operator \(\hat{d}\) (~1,000 e a0, with a0 the Bohr radius). For Rydberg atoms with principal quantum number n = 40, distant by R ≈ 1 μm (to trap them in independent tweezers), the coupling strength between pairs of orbitals (r) reaches \(J=\langle r^{\prime} r^{\prime\prime} | {\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{dip}}}}}| rr\rangle \approx 2\uppi \times 1\) GHz, which sets the speed limit of entanglement at tJ ≈ 1 ns—five orders of magnitude faster than the 100 μs radiative lifetime of Rydberg states (Fig. 1a). The best entangling protocols of Rydberg atoms28,29,30,31 are currently performed deeply in the adiabatic regime compared with the available interaction strength, with a typical duration of 0.5 μs, as they rely on Rydberg blockade35. In this scenario, the interaction strength—either the dipole–dipole coupling, J, or more often the weaker second-order van der Waals shift, V—is larger than the coupling ΩCW from ground to Rydberg states with continuous-wave (CW) lasers, such that excitation of two atoms is prohibited. This gives rise to entanglement on a timescale π/ΩCW ≫ tJ, which is technically limited by the available power of CW lasers, and is orders of magnitude longer than possible with the available gigahertz interaction strength.

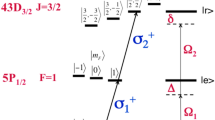

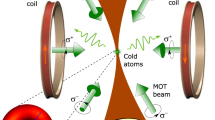

a, Rydberg physics timescale. ΩCW and ΩP are the typical laser couplings to a Rydberg state with CW and pulsed lasers, respectively. b, Experimental set-up: the 780 and 480 nm picosecond laser pulses are shined—along the quantization axis (y)—on the atoms trapped at the focus of the objective to excite them to a Rydberg state. c, Averaged fluorescence image of the atomic array containing 14 × 16 pairs of atoms. All pairs are aligned along the quantization axis. The Rydberg experiments are performed with the column highlighted blue, where the intensity of the 480 nm pulsed laser is highest. d, Magnification on a pair of atoms for a few R. e, Raman sideband spectra—averaged over all atoms—for two orientations of the Raman beams (orange, x and y; black, y and z) showing all three modes of atomic motion at the trap frequencies ωx,y,z = 2π × (147, 117, 35) kHz (dashed lines). From the asymmetry of the sidebands we extract the mean motional number for each mode \({\bar{n}}_{x,y,z}=(0.11,0.11,0.56)\).

Here we explore a novel ultrafast direction to realize an entanglement protocol with Rydberg atoms at the speed limit set by the dipole–dipole interaction. Holographic tweezers are used to trap single ultracold 87Rb atoms, which are separated by R as small as 1.5 μm, with precision limited by quantum fluctuations of the atoms in their traps. The single valence electrons of these atoms are then both efficiently excited simultaneously to a nD Rydberg state by using ultrashort laser pulses with a duration of 10 ps—much faster than the timescale of interaction and thus far beyond the Rydberg blockade36,37, but slow enough to resolve Rydberg orbitals. A natural resonance between the pair states \(\left|43D,43D\right\rangle\) and \(\left|45P,41F\right\rangle\) then gives rise to a coherent energy exchange, that is, Förster oscillation38,39. This interaction-driven dynamics ideally imprints a conditional π-phase shift \(\left|43D,43D\right\rangle \to {e}^{i\uppi }\left|43D,43D\right\rangle\) after a time t = π/J: the key resource for a controlled-Z (CZ) gate10,21,22,23,28,29, enabling quantum computing.

Results

Pair of ultracold atoms with tunable spacing

The experiment starts by trapping single 87Rb atoms in a two-dimensional array of optical tweezers obtained by focusing a 810 nm trapping beam with a high-NA objective (Fig. 1b). The use of a 0.75 NA objective—unusually large for atom-tweezers experiments—is motivated by the achievable narrow beam waist (~0.6 μm; see Methods for a complete characterization of the tweezers). This allows one to bring two tweezers to a closer R where interactions are stronger. The array of tweezers—comprising pairs of traps with adjustable spacing ranging from 1.5 to 5 μm (Fig. 1c,d)—is engineered by imprinting a phase hologram on the trapping beam with a spatial light modulator. We sum two holograms: one computed by the weighted Gerchberg–Saxton algorithm to generate a regular two-dimensional array, and the other a binary phase grating with a tunable period to diffract each single trap into a pair.

By operating in a regime where the dynamics is driven by the dipole–dipole interaction J = C3/R3, with C3 the interaction coefficient (by contrast to the blockade dynamics driven by the laser coupling ΩCW), it becomes crucial to precisely control the inter-atomic R and to minimize its uncertainty (ΔR) as it translates into an interaction noise ΔJ/J = 3ΔR/R. A first source of error is the distance between two traps. To address this, we extract the position of the tweezers from the fluorescence images of the trapped atoms (such as in Fig. 1), with a fitting uncertainty of less than 10 nm, giving an error of ΔR/R ≈ 1%. The next source of uncertainty is the atom position in the trap. Experiments with Rydberg atoms in tweezers are usually performed with hot atoms (T ≈ 30 μK) with large fluctuations on the order of \(\sqrt{{k}_{\mathrm{B}}T/m{\omega }^{2}} \approx 100\) nm (500 nm along z), which are only tolerable as these experiments rely on blockade, or because large distances (R ≈ 10 μm) are used24,40,41. This gives an unacceptable thermal uncertainty (ΔRth/R ≈ 10%) that would strongly affect the interaction-driven dynamics. These thermal fluctuations can be suppressed by applying Raman sideband cooling to bring the atoms into the quantum motional ground state of the optical traps. Although this technique has been demonstrated for a few tweezers42,43, scaling up is made challenging by trap inhomogeneities over the large array. To overcome this issue, we introduce the use of adiabatic cooling pulses with hyperbolic-secant profiles that address all atoms with high efficiency44. After this cooling step, we perform Raman sideband spectroscopy (see Fig. 1e) and extract the remaining mean motional quanta \({\bar{n}}_{x,y,z}=(0.11,0.11,0.56)\) along each direction. This translates into a position spread \(\sqrt{\bar{n}+1/2}\sqrt{\hslash /m\omega }=(22,25,60)\) nm and thus a quantum uncertainty ΔRqu = 35 nm (ΔRqu/R < 2%) dominated at 90% by zero-point quantum fluctuations. This combination of holographic tweezers and robust Raman sideband cooling allows fast preparation of two ultracold atoms with a well-defined wavefunction ψ(R) that describes the relative position of the two atoms.

Ultrafast pulsed excitation to Rydberg states

We then proceed with the ultrafast coherent transfer of atoms to Rydberg orbitals. Although CW laser technology has proven to be effective for high-fidelity manipulation of Rydberg states29,30,45, excitation typically requires more than 100 ns. Pulsed-laser technology, offering much higher peak power, has enabled the excitation of a single Rydberg state in nanoseconds46,47,48 and even down to 10 ps (refs. 36,37), reaching the limit set by the Rydberg level spacing \({({{\Delta }}{E}_{n}/{{\Delta }}n)}^{-1}\). However, this picosecond excitation is so far limited to an efficiency of 3%, which is far from the unit-fidelity requirement for quantum information processing. Here we demonstrate a scheme allowing near-unity population transfer to a Rydberg state comprising two single-photon Rabi π-pulses (Fig. 1b). First, a 2 ps pulse at 780 nm transfers more than 95% of electronic population from the ground state \(\left|g\right\rangle =\left|5S\right\rangle\) to the intermediate state \(\left|e\right\rangle =\left|5P\right\rangle\). A 480 nm laser pulse then performs the excitation to the Rydberg state \(\left|d\right\rangle =\left|43D\right\rangle\). To resolve the Rydberg series, the pulse spectrum is cut, giving a longer duration of 14 ps. We achieved a peak Rabi frequency of up to ΩP ≈ 2π × 60 GHz, allowing one to drive Rabi oscillations greater than 2π. Adjusting the pulse energy for a π-pulse, we obtain a maximum population transfer of 75% to the Rydberg state—a factor of 20 larger than in previous demonstrations. This is currently limited by pulse-to-pulse energy fluctuation of the commercial 480 nm source, and would be improved with a more stable pulsed-laser system. Optical pumping and polarizations of the lasers ensure that we saturate the projection of orbital angular momentum \(\left|{m}_{L}=2\right\rangle\) while decoupling the spin DOF. The excitation is performed fast enough to neglect spontaneous emission from the 5P orbital (25 ns), as well as interaction.

Ultrafast Förster oscillation

Following excitation, atoms in state \(\left|dd\right\rangle =\left|43D;43D\right\rangle\) experience the effect of \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{dip}}}}}\) dominated by the coupling to the state \(\left|pf\right\rangle =\left|45P;41F\right\rangle\), as shown in Fig. 2. The detuning ΔE of this channel is especially small (−8 MHz), leading to the so-called Förster oscillation between \(\left|dd\right\rangle\) and the symmetric state \(|\tilde{pf}\rangle =\left(\left|pf\right\rangle +\left|fp\right\rangle \right)/\sqrt{2}\) with a coupling of \(J=\sqrt{2}{C}_{3}/{R}^{3}\). With increasing interaction time t, the atoms evolve into \(\left|{{\varPsi }}(t)\right\rangle =\cos (Jt)\left|dd\right\rangle -i\sin (Jt)|\tilde{pf}\rangle\), and at t = π/J they are back into state \(-\left|dd\right\rangle\) having acquired a π-phase shift. A refined description of the system requires to account for the finite size ΔRqu of the wavefunction ψ(R). We emphasize that, having efficiently suppressed thermal fluctuations, the coupling between the electron dynamics and atomic motion becomes coherent. This leads to the following entangled state of internal and external DOF:

a,b, Single-atom spectrum showing dipole matrix elements d from state 43D (a) and the different mL sublevels (b), highlighting the selection rule for a pair of atoms aligned with the quantization axis. Atomic orbitals for mL = L are represented. c, Two-atom spectrum obtained by diagonalizing \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{dip}}}}}\). The inset shows ∣C3∣ = d1d2/4πϵ0 coupling and the energy difference between the relevant pair states. The resonant coupling gives a splitting \(J=\sqrt{2}{C}_{3}/{R}^{3}\) between the two eigenstates (solid lines), whereas the off-resonant channel adds a van der Waals shift \(V=-{(\sqrt{2}{C}_{3}/{R}^{3})}^{2}/{{\Delta }}E\) (dashed lines). The probability distribution ∣ψ(R)∣2 is shown for the measured ΔRqu = 35 nm.

Other channels or DOF could perturb this dynamics. We find that \(\left|44P;42F\right\rangle\) is the next relevant channel and that it adds a perturbative V (Fig. 2c). Other dipole–dipole channels, as well as higher-order ones (for example, dipole–quadrupole channels) are more negligible: they are left out of the discussion but considered in numerical simulations49,50. Finally, we ensure that mL remains decoupled from the Rydberg dynamics, as shown in Fig. 2b.

To observe the Förster oscillation, we perform the pump–probe experiment illustrated in Fig. 3a. A pair of identical 480 nm pulses are generated from a single pulse going through a delay-line Mach–Zehnder interferometer, with an adjustable delay t of up to 6.5 ns. The first 480 nm π-pulse brings the atoms to state \(\left|d\right\rangle\), initiating the interaction-driven dynamics. After a delay t, a second π-pulse de-excites the atoms remaining in state \(\left|d\right\rangle\) to state \(\left|e\right\rangle\). Figure 3b,d shows the probability for atoms to be detected in state \(\left|d\right\rangle\) as a function of the measured R, which is varied by adjusting the binary phase grating. We also display the oscillation as a function of the interaction area \(Jt=\sqrt{2}{C}_{3}t/{R}^{3}\) (Fig. 3c,e). The period matches the ab initio theory (dotted curves) for the two datasets, clearly demonstrating that the dynamics is coherently driven by the identified Förster channel, even at such a close R.

a, Pump–probe sequence. b–e, Probability Pd for the atom to be in state \(\left|d\right\rangle\) after t = 2.29 ns (b,c) or t = 6.51 ns (d,e). The oscillation is shown as a function of R (b,d) or the interaction area \(Jt=\sqrt{2}{C}_{3}t/{R}^{3}\) (c,e). The black curves are parameter-free simulations of the ideal Förster oscillation rescaled by the SPAM errors (dotted lines), including the effect of quantum uncertainty in position (dashed lines) and perturbing interaction channels (solid lines). In e we show the data of all 16 pairs of atoms, whereas this is averaged in b–d. For each R, we repeat the experiment 2,000 times, out of which we select the ~25% of shots where both atoms of a pair are loaded, resulting in a quantum projection noise <3% for each point in e, and <1% in b–d.

We now discuss the contrast and damping of the oscillation. The finite contrast is not inherent in the interaction-driven dynamics but is caused by state preparation and measurement (SPAM) errors that originate from imperfect preparation in state \(\left|d\right\rangle\), which would be improved by replacing the laser system with a more stable one. These errors are independently measured and used to rescale simulations. Concerning the damping, a first source is the quantum uncertainty of R. Calculations that involve tracing over R (see equation (1)) demonstrate that this effect is responsible for most of the damping for large values of Jt, as clearly seen in Fig. 3e. The presence of perturbing off-resonant channels (solid lines) gives a more pronounced leakage in Fig. 3c, where we use smaller R, which increases the perturbation. By plotting data for each pair, we also notice a horizontal scatter that increases with Jt, pointing to errors in the measured R. Eventually, there remains a slight discrepancy in damping that is attributed to imperfect laser polarization leading to coupling of the Förster dynamics with the mL DOF. These last two technical points could be addressed in future experiments by devising additional in situ measurements of R and laser polarization.

Conditional phase

We next investigate the conditional phase ϕ imprinted on a pair of atoms. To this end, we consider atoms initialized in a coherent superposition of states \(\left|e\right\rangle +\left|d\right\rangle\). The interaction drives the state of atom 1 of a pair into \(\left|e\right\rangle +| c| {e}^{i\phi }\left|d\right\rangle\) when atom 2 in state \(\left|d\right\rangle\) (whereas nothing happens when atom 2 is in state \(\left|e\right\rangle\)), where \(| c| {e}^{i\phi }=\cos (Jt)\) would realize a CZ gate when ϕ = π at Jt = π. Having measured the population ∣c∣2 above, we now gain sensitivity to ϕ by performing a Ramsey interferometry experiment36,51,52,53,54. Our Ramsey pump–probe technique can directly visualize the ultrafast temporal oscillation of the superposition with attosecond precision and a period of 1.6 fs in real time36,53, and can thus monitor ϕ directly.

As depicted in Fig. 4a, a first π/2-pulse prepares the coherent superposition of states \(\left|e\right\rangle +\left|d\right\rangle\) in each of the atoms 1 and 2. The temporal oscillation of the superposition in atom 1 is monitored after an interaction time t = 6.51 ns with a second π/2-pulse. The passively stable delay-line Mach–Zehnder interferometer is used to finely scan for the arrival of this second pulse over 3 fs with attosecond precision to record a Ramsey fringe with period T = h/(Ed − Ee) = 1.6 fs, which is given by the energy difference between the two states. The Ramsey signal given by atom 1—conditioned on the state of atom 2—could be observed with single-atom addressing techniques9,29. Here, Ramsey fringes are recorded irrespective of the state of atom 2 (refs. 41,55), thus giving a signal from atom 1 that oscillates with the phase θ of the second laser pulse (in the rotating frame) as \(\frac{1}{2}[\cos (\theta )+| c| \cos (\theta +\phi )]={C}_{\mathrm{R}}\cos (\theta +{\theta }_{\mathrm{R}})\), where the first and second terms on the left side correspond with atom 2 in states \(\left|e\right\rangle\) and \(\left|d\right\rangle\), respectively. We compare this signal with reference fringes obtained with single isolated atoms (oscillating as \(\cos (\theta )\)) and extract the relative contrast CR and phase shift θR.

a, The Ramsey pump–probe sequence. b, Ramsey fringes for Jt = 0.1π, π, 2π (R = 5, 2.4, 1.9 μm) when one (grey circles) or two (red circles) atoms are loaded in a pair of tweezers. The fine delay offset is arbitrarily defined to be 0 fs in each interferogram. c, CR and θR extracted from b with numerical simulations. Calculations are represented by lines, whereas measurements are represented by points. Error bars are the s.e.m. from the fitting routine of the Ramsey fringes. d, Bloch sphere representation of the state of atom 1, which remains in state \(\left|e\right\rangle +\left|d\right\rangle\) when atom 2 is in state \(\left|e\right\rangle\), but is driven into \(\left|e\right\rangle +| c| {e}^{i\phi }\left|d\right\rangle\) when atom 2 is in state \(\left|d\right\rangle\). Trajectories are shown for three scenarios depending on the parameters (J, V, ΔE) illustrated in e: resonant energy exchange V = ΔE = 0 (red arrow), real parameters (J, V, ΔE)/(2π) = (75, −23, −8) MHz at R = 2.4 μm (blue arrow) and with envisioned active correction ΔE = −V (green arrow).

In Fig. 4b we show the signals for Jt = 0, π and 2π. At Jt = π, the interaction should ideally produce a maximally entangled state of the two atoms giving a signal with zero contrast (∣c∣ = 1, ϕ = π → CR = 0), and we have indeed observed a strong reduction of the contrast. At Jt = 2π, the atoms should be returned back to a pure product state and the contrast should revive (∣c∣ = 1, ϕ = 2π → CR = 1, θR = 0), and we have observed this revival. Our result shown in Fig. 4b thus demonstrates that ϕ ≈ π for the CZ gate at Jt = π. However, there are deviations from this ideal picture: there is a finite contrast and small phase shifts of the Ramsey fringes.

To fully understand these deviations quantitatively, we now account for the V caused by perturbing channels and the energy defect ΔE of the resonance. In the limit V, ΔE ≪ J, we can derive \(| c| {e}^{i\phi }\simeq \cos (Jt){e}^{-i(V+{{\Delta }}E)t/2}\), as represented on the Bloch sphere, which modifies the expected Ramsey contrast and phase shift as shown in Fig. 4c. The excellent agreement between calculations and measurements supports that we accurately capture the evolution of ϕ. For our experimental parameters, we calculate ϕ = 1.17π, thus overshooting the ideal π-phase shift. This could be corrected by tuning the energy of the \(\left|pf\right\rangle\) state to ΔE = − V with a weak electric field (<1 V cm–1) applying a Stark shift. Finally, we point that a related procedure was used by Jo and colleagues41 to obtain the ϕ between Rydberg atoms at a distance R ≈ 10 μm (using a pure van der Waals coupling) in a time of π/V = 2.6 μs. Here we demonstrate 400-fold-faster dynamics thanks to the use of ultrafast pulsed-laser technology to excite Rydberg atoms, and much closer distances that bring the interaction strength towards the gigahertz range.

Discussion

We now compare the two scenarios to generate entanglement with Rydberg atoms: laser-driven Rydberg blockade and the interaction-driven dynamics explored here. The advantage of Rydberg blockade, already identified in the seminal proposal35, is the suppression of population of the strongly interacting state \(\left|rr\right\rangle\), thus avoiding: (1) leakage into other Rydberg states \(\left|r^{\prime} r^{\prime\prime} \right\rangle\), and (2) motional coupling to the atoms’ external DOF (\(\hat{x},\hat{p}\)) caused by the distance-dependent dipole–dipole interaction. This makes it robust to the details of the dipole–dipole Hamiltonian and to position uncertainty. On the other hand, this slow blockade approach requires to spend a relatively long time in Rydberg states affected by finite lifetime, black-body radiation56, the Doppler effect, laser phase noise45,57, electric field fluctuation and motional coupling due to different trapping potentials of ground and Rydberg atoms in tweezers58,59.

The ultrafast interaction-driven approach does not suffer from such sources of decoherence as it is two orders of magnitude faster, but is however affected by unitary errors caused by points (1) and (2). Promisingly, other communities have learned to minimize exactly such effects (for example, leakage to non-computational states in superconducting qubits20, motional coupling in ion traps15) while approaching the entanglement speed limit10,17,18,21,22,23. Applying such techniques to our ultrafast Rydberg platform could help to control coherent errors. For example, the effects of perturbing channels (that is, leaks in other pair states \(\left|r^{\prime} r^{\prime\prime} \right\rangle\) and dynamical phases) can be eliminated by fine-tuning their energy using electric38,52 or microwave fields60 to achieve synchronization of maximal entanglement and minima of leaks as performed with superconducting qubits10,21,22,23. One could also dynamically adjust the Förster resonance defect ΔE to perform robust fast adiabatic gates20. The fundamental source of infidelity for an interaction-driven gate then becomes the entanglement with the external DOF of the atoms, with the quantum uncertainty in distance leading to a leakage in \(\left|pf\right\rangle\) of (3πΔR/R)2 = 1.8%. We envision that coherent control techniques can further suppress such errors, for example, by preparing squeezed states of motions to reduce the position uncertainty below the limit set by the ground-state wavefunction61,62 or by using a decoupling echo-like sequence that can remove the entanglement with the external DOF similar to the one proposed for Rydberg atoms16 or used in ultrafast trapped-ion experiments15,17,18.

In summary, we combined ultrafast pulsed-laser technology and state-of-the-art control of atoms with optical tweezers to prepare a pair of Rydberg atoms with an inter-atomic distance down to 1.5 μm, controlled with a precision limited by quantum fluctuations. These techniques allow one to directly use the strong interaction between a close-by pair of Rydberg atoms, going far beyond what is achievable in the usual Rydberg blockade regime. We demonstrate this by observing an ultrafast interaction-driven energy exchange giving rise to a calculated ϕ = 1.17π, in excellent agreement with measurements; this ϕ is acquired in only 6.5 ns—over 100-times faster than in any other Rydberg experiments so far—and is the key resource for a novel ultrafast two-qubit gate operating at the fundamental speed limit set by the dipole–dipole Hamiltonian. The next steps towards an ultrafast CZ gate would be to replace the commercial excitation laser with a more stable homemade system to improve the issue of excitation fidelity; to combine the ultrafast excitation with encoding of a long-lived qubit in the hyperfine ground states6; and to implement the aforementioned coherent control techniques to manage the identified residual couplings to other pair states and motional DOF. Furthermore, our experimental platform could also be used to simulate the dynamics of interacting spin-1 models naturally implemented by the Förster resonance, to investigate Rydberg interactions when orbitals of neighbor atoms overlap37, or the use of Rydberg wavepackets51 instead of single levels.

Methods

In the first section we describe the tweezers array and the experimental routine, whereas in the second we provide further information on ultrafast Rydberg excitation, and the decoupling of spin and orbital DOF during Rydberg dynamics.

Tweezers set-up

Individual tweezers

We use optical tweezers to trap and confine a single atom at their focus, where the dipole potential is well approximated by an anisotropic harmonic trap that is characterized by a set of trap frequencies, ω, and a trap depth, U0. These quantities are determined for each tweezer with a precision of 1%, and they vary over the trap array by ~10%. The trap frequencies are determined from Raman sideband spectra, giving (ωx, ωy, ωz) = 2π × (147, 117, 35) kHz, and they solely determine the spread of the motional ground-state wavefunction \(\sqrt{\hslash /2m\omega }\), where m is the mass of 87Rb. By combining the trap frequencies with an independent measurement of the trap depth U0 = kB × 0.62 mK (= h × 13 MHz), and assuming a Gaussian beam, we calculate a tweezers waist of 0.53/0.62 μm and a Rayleigh length of 1.56 μm, which is within 15% of the diffraction theory limit for the NA = 0.75 used here. We note that the tweezers radial anisotropy of 20% is not caused by aberrations, but naturally emerges from vector diffraction theory, which predicts a 18% larger waist along the tweezers' linear polarization (y) at our NA.

Distance and alignment of the pairs of tweezers

The dipole–dipole interaction depends on R between pairs of atoms, as well as the relative angle with the quantization axis. We extract the inter-atomic distance from fluorescence images giving the x, y position of each atom with a fitting precision of 10 nm. The magnification of the imaging system was calibrated to better than 1% by using a 390 nm standing-wave as an in situ ruler. More precisely, we retro-reflect the 780 nm optical pumping beam resonant on the \(\left|5{S}_{1/2},F=2\right\rangle \to \left|5{P}_{3/2},F=2\right\rangle\) transition. This gives a scattering rate spatially modulated with a period of 390 nm, allowing one to calibrate the atoms’ positions. In addition, this optical pumping beam defines the quantization axis such that this measurement is also used to adjust the angle between a pair of atoms to the quantization axis. Finally, we note that we do not measure the z-positions of the atoms and assume that they all lie in the same z-plane. In future experiments, this could be improved by observing the atomic fluorescence in different planes, or by using the standing-wave ruler method described above with a projection along the optical axis of the microscope.

Experimental routine

Single atoms are randomly loaded in the tweezers from a magneto-optical trap and detected by collecting fluorescence photons during 10 ms on an electron-multiplying CCD camera at the beginning and the end of each experiment, with a fluorescence detection fidelity > 97%. We post-select the runs where one or two traps of a given pair are loaded when necessary. At the end of each Rydberg experiment and before the second fluorescence image, we apply a large electric field to field-ionize any atoms left in Rydberg states, while others are recaptured in the tweezers and detected. The experiments are repeated every 150 ms to accumulate statistics.

Ultrafast Rydberg excitation

Picosecond laser pulses

We describe here the procedure for ultrafast coherent excitation of Rydberg atoms. A titanium:sapphire regenerative amplifier (Spectra Physics; Spitfire Ace) delivers Fourier-transform-limited 780 nm pulses at a repetition rate of 1 kHz and average power of 5 W, with a spectrum centered on the g ↔ e transition and a bandwidth of 700 GHz. A small percentage of the pulse energy is picked up to directly drive the transition to the first excited state, with the energy adjusted to achieve a Rabi π-pulse. The remaining power pumps an optical parametric amplifier (Spectra Physics; TOPAS) to generate 480 nm pulses with an average power of 0.2 W and a 1-THz-wide spectrum centered on the transition to the selected 43D Rydberg state. To account for the finite energy splitting of the Rydberg series, we cut the 480 nm bandwidth down to 100 GHz to avoid exciting the nearby 42D and 44D levels36, as checked by numerical simulations. For convenience, we also estimate the duration of these pulses (2 ps and 14 ps, respectively) by deriving them from their bandwidth and approximating their temporal and spectral profiles by Gaussian functions. To achieve sufficient driving strength on the weak e ↔ d transition, we focus the 480 nm beam to a diameter of 20 μm; consequently only a single column of the array experiences the maximum intensity. In this configuration, we succeed in driving more than 2π cycles with a single pulse, or two π-pulses in a pump–probe configuration.

Large pulse-to-pulse energy fluctuation (30%) of the 480 nm laser currently limits the π-pulse fidelity to 75%. We found that these technical fluctuations originate in the non-linear processes used to generate the 480 nm pulse from a stable 780 nm pump36, which comprises optical parametric generation (to create a 1,248 nm seed), optical parametric amplification (to amplify the seed) and sum-frequency generation (of 1,248 nm and 780 nm to generate the 480 nm pulse). We plan to use a carefully designed wavelength conversion system, instead of the general purpose commercial product currently used, for suppressing these power fluctuations δP and increasing the fidelity \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) of transfer to Rydberg state, that scales as a \(1-{{{\mathcal{F}}}}\propto {(\delta P)}^{2}\). To obtain the excitation fidelity \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\), which exceeds 99%, we need to control the power fluctuation to be below 10%.

Spin DOF

We justify here the decoupling of the spin (mS, mI) DOF from the Rydberg dynamics. Although the nuclear spin mI has negligible coupling with Rydberg orbitals (<100 kHz), the electronic spin mS experiences strong spin–orbit coupling (~1 GHz on P orbitals, ~100 MHz on D orbitals at n ≃ 40). To avoid entanglement with this spin DOF, we apply optical pumping before excitation to spin-polarize the atoms in the ground-state \(\left|F=2,{m}_{F}=2\right\rangle =\left|{m}_{L}=0;\,{m}_{S}=1/2,{m}_{I}=3/2\right\rangle\) and adjust the polarization of the lasers to σ+ to prepare the Rydberg state in a decoupled angular momentum state \(\left|43D,{m}_{L}=2\right\rangle \left|{m}_{S}=1/2,{m}_{I}=3/2\right\rangle\).

Orbital DOF

We justify here the decoupling of the orbital (mL) DOF from the Rydberg dynamics. This projection of orbital angular momentum mL could evolve upon action of the dipole–dipole Hamiltonian \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{dip}}}}}\), which contains terms changing each atom angular momentum by ΔmL = 0, ± 1. By preparing atoms with saturated \(\left|{m}_{L}=L=2\right\rangle\) and by aligning the pair of atoms with the quantization axis such that the total angular momentum projection is conserved, we ensure that mL = L throughout the dynamics which effectively decouples this DOF.

Data availability

Source Data for Figs. 3 and 4 are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6640418 (ref. 63).

References

Veldhorst, M. et al. An addressable quantum dot qubit with fault-tolerant control-fidelity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 981–985 (2014).

Kono, S. et al. Breaking the trade-off between fast control and long lifetime of a superconducting qubit. Nat. Commun. 11, 3683 (2020).

Cantat-Moltrecht, T. et al. Long-lived circular Rydberg states of laser-cooled rubidium atoms in a cryostat. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 022032(R) (2020).

Wang, P. et al. Single ion qubit with estimated coherence time exceeding one hour. Nat. Commun. 12, 233 (2021).

Somoroff, A. et al. Millisecond coherence in a superconducting qubit. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2103.08578 (2021).

Campbell, W. C. et al. Ultrafast gates for single atomic qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 090502 (2010).

Takeda, K. et al. A fault-tolerant addressable spin qubit in a natural silicon quantum dot. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600694 (2016).

Song, Y., Lee, H.-g, Kim, H., Jo, H. & Ahn, J. Subpicosecond X rotations of atomic clock states. Phys. Rev. A 97, 052322 (2018).

Zhang, C. et al. Submicrosecond entangling gate between trapped ions via Rydberg interaction. Nature 580, 345–349 (2020).

Barends, R. et al. Diabatic gates for frequency-tunable superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 210501 (2019).

Mølmer, K. & Sørensen, A. Multiparticle entanglement of hot trapped ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 1835–1838 (1999).

DiCarlo, L. et al. Demonstration of two-qubit algorithms with a superconducting quantum processor. Nature 460, 240–244 (2009).

Wilk, T. et al. Entanglement of two individual neutral atoms using Rydberg blockade. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 010502 (2010).

Isenhower, L. et al. Demonstration of a neutral atom controlled-NOT quantum gate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 010503 (2010).

García-Ripoll, J. J., Zoller, P. & Cirac, J. I. Speed optimized two-qubit gates with laser coherent control techniques for ion trap quantum computing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 157901 (2003).

Cozzini, M., Calarco, T., Recati, A. & Zoller, P. Fast Rydberg gates without dipole blockade via quantum control. Optics Commun. 264, 375–384 (2006).

Wong-Campos, J. D., Moses, S. A., Johnson, K. G. & Monroe, C. Demonstration of two-atom entanglement with ultrafast optical pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 230501 (2017).

Schäfer, V. M. et al. Fast quantum logic gates with trapped-ion qubits. Nature 555, 75–78 (2018).

Hussain, M. I. et al. Ultraviolet laser pulses with multigigahertz repetition rate and multiwatt average power for fast trapped-ion entanglement operations. Phys. Rev. Applied 15, 024054 (2021).

Martinis, J. M. & Geller, M. R. Fast adiabatic qubit gates using only σz control. Phys. Rev. A 90, 022307 (2014).

Rol, M. A. et al. Fast, high-fidelity conditional-phase gate exploiting leakage interference in weakly anharmonic superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 120502 (2019).

Foxen, B. et al. Demonstrating a continuous set of two-qubit gates for near-term quantum algorithms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 120504 (2020).

Negîrneac, V.High-fidelity controlled-Z gate with maximal intermediate leakage operating at the speed limit in a superconducting quantum processor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 220502 (2021).

de Léséleuc, S. et al. Observation of a symmetry-protected topological phase of interacting bosons with Rydberg atoms. Science 365, 775–780 (2019).

Scholl, P. et al. Quantum simulation of 2D antiferromagnets with hundreds of Rydberg atoms. Nature 595, 233–238 (2021).

Ebadi, S. et al. Quantum phases of matter on a 256-atom programmable quantum simulator. Nature 595, 227–232 (2021).

Bluvstein, D. et al. Controlling quantum many-body dynamics in driven Rydberg atom arrays. Science 371, 1355–1359 (2021).

Levine, H. et al. Parallel implementation of high-fidelity multiqubit gates with neutral atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 170503 (2019).

Graham, T. M. et al. Rydberg-mediated entanglement in a two-dimensional neutral atom qubit array. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 230501 (2019).

Madjarov, I. S. et al. High-fidelity entanglement and detection of alkaline-earth Rydberg atoms. Nat. Phys. 16, 857–861 (2020).

Fu, Z. et al. High fidelity entanglement of neutral atoms via a Rydberg-mediated single-modulated-pulse controlled-phase gate. Phys. Rev. A 105, 042430 (2022).

Morgado, M. & Whitlock, S. Quantum simulation and computing with Rydberg-interacting qubits. AVS Quantum Sci. 3, 023501 (2021).

Saffman, M., Walker, T. G. & Mølmer, K. Quantum information with Rydberg atoms. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 2313–2363 (2010).

Browaeys, A. & Lahaye, T. Many-body physics with individually controlled Rydberg atoms. Nat. Phys. 16, 132–142 (2020).

Jaksch, D. et al. Fast quantum gates for neutral atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 2208–2211 (2000).

Takei, N. et al. Direct observation of ultrafast many-body electron dynamics in an ultracold Rydberg gas. Nat. Commun. 7, 13449 (2016).

Mizoguchi, M. et al. Ultrafast creation of overlapping Rydberg electrons in an atomic BEC and Mott-insulator lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 253201 (2020).

Ravets, S. et al. Coherent dipole–dipole coupling between two single Rydberg atoms at an electrically-tuned Förster resonance. Nat. Phys. 10, 914–917 (2014).

Ravets, S., Labuhn, H., Barredo, D., Lahaye, T. & Browaeys, A. Measurement of the angular dependence of the dipole–dipole interaction between two individual Rydberg atoms at a Förster resonance. Phys. Rev. A 92, 020701(R) (2015).

Lienhard, V. et al. Realization of a density-dependent Peierls phase in a synthetic, spin–orbit coupled Rydberg system. Phys. Rev. X 10, 021031 (2020).

Jo, H., Song, Y., Kim, M. & Ahn, J. Rydberg atom entanglements in the weak coupling regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 033603 (2020).

Kaufman, A. M., Lester, B. J. & Regal, C. A. Cooling a single atom in an optical tweezer to its quantum ground state. Phys. Rev. X 2, 041014 (2012).

Thompson, J. D., Tiecke, T. G., Zibrov, A. S., Vuletić, V. & Lukin, M. D. Coherence and Raman sideband cooling of a single atom in an optical tweezer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 133001 (2013).

Garwood, M. & DelaBarre, L. The return of the frequency sweep: designing adiabatic pulses for contemporary NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 153, 155–177 (2001).

Levine, H. et al. High-fidelity control and entanglement of Rydberg-atom qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 123603 (2018).

Huber, B. et al. GHz Rabi flopping to Rydberg states in hot atomic vapor cells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 243001 (2011).

Urvoy, A. et al. Strongly correlated growth of Rydberg aggregates in a vapor cell. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 203002 (2015).

Ripka, F., Kübler, H., Löw, R. & Pfau, T. A room-temperature single-photon source based on strongly interacting Rydberg atoms. Science 362, 446–449 (2018).

Šibalić, N., Pritchard, J., Adams, C. & Weatherill, K. ARC: an open-source library for calculating properties of alkali Rydberg atoms. Comput. Phys. Commun. 220, 319–331 (2017).

Weber, S. et al. Tutorial: calculation of Rydberg interaction potentials. J. Phys. B 50, 133001 (2017).

Ahn, J., Weinacht, T. C. & Bucksbaum, P. H. Information storage and retrieval through quantum phase. Science 287, 463–465 (2000).

Nipper, J. et al. Atomic pair-state interferometer: controlling and measuring an interaction-induced phase shift in Rydberg–atom pairs. Phys. Rev. X 2, 031011 (2012).

Liu, C. M. et al. Attosecond control of restoration of electronic structure symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 173201 (2018).

Bharti, V. et al. Ultrafast many-body electron dynamics in an ultracold Rydberg-excited atomic Mott insulator. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.09590 (2022).

Mandel, O. et al. Controlled collisions for multi-particle entanglement of optically trapped atoms. Nature 425, 937–940 (2003).

Festa, L. et al. Black-body radiation induced facilitated excitation of Rydberg atoms in optical tweezers. Phys. Rev. A 105, 013109 (2022).

de Léséleuc, S., Barredo, D., Lienhard, V., Browaeys, A. & Lahaye, T. Analysis of imperfections in the coherent optical excitation of single atoms to Rydberg states. Phys. Rev. A 97, 053803 (2018).

Barredo, D. et al. Three-dimensional trapping of individual Rydberg atoms in ponderomotive bottle beam traps. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 023201 (2020).

Wilson, J. et al. Trapped arrays of alkaline earth Rydberg atoms in optical tweezers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 033201 (2022).

Zhang, C. et al. Submicrosecond entangling gate between trapped ions via Rydberg interaction. Nature 580, 345–349 (2020).

Morinaga, M., Bouchoule, I., Karam, J.-C. & Salomon, C. Manipulation of motional quantum states of neutral atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 4037–4040 (1999).

Burd, S. C. et al. Quantum amplification of mechanical oscillator motion. Science 364, 1163–1165 (2019).

Chew, Y. et al. Replication Data for: “Ultrafast Energy Exchange Between two Single Rydberg Atoms on the Nanosecond Timescale" (Zenodo, 2022); https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6640418

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge D. Barredo, A. Browaeys, D. Jaksch, T. Lahaye and M. Weidemüller for fruitful discussions on this work. We thank Z. Meng, V. Bharti and N. Takei for contributions at the early stage of this work; R. Villela for a careful reading of the manuscript; and Y. Okano, T. Toyoda, M. Aoyama and H. Chiba for the technical support. We thank R. Iino and R. Yokokawa for helpful discussions on the development of the objective lens and for providing equipment to evaluate its performance. We thank Y. Ohbayashi from Hamamatsu Photonics K.K. for coating the viewports, and H. Toyoda, Y. Ohtake, T. Ando, H. Sakai, Y. Takiguchi and K. Nishimura for fruitful discussions about the optical system and providing the spatial light modulator. This work was supported by MEXT Quantum Leap Flagship Program (MEXT Q-LEAP) JPMXS0118069021 and JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research (grant no. 16H06289). T.T. and S.d.L. acknowledge partial support by JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Research Activity Start-up (grant nos. 19K23431 and 19K23429 respectively). K.O. acknowledges partial support by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and Heidelberg University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C., T.T., T.P.M. and S.d.L. designed and carried out the experiments. Y.C. and S.d.L. performed data analysis, theory and simulations, and wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. S.d.L. and K.O. supervised and guided this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Photonics thanks Markus Hennrich, Sebastian Hofferberth and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chew, Y., Tomita, T., Mahesh, T.P. et al. Ultrafast energy exchange between two single Rydberg atoms on a nanosecond timescale. Nat. Photon. 16, 724–729 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-022-01047-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-022-01047-2

This article is cited by

-

Ultrafast quantum control of atomic excited states via interferometric two-photon Rabi oscillations

Communications Physics (2024)

-

High-fidelity parallel entangling gates on a neutral-atom quantum computer

Nature (2023)

-

Floquet-tailored Rydberg interactions

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Ultrafast interaction between Rydberg atoms

Nature Photonics (2022)