Abstract

Chlorpyrifos-resistant (Rc) Plutella xylostella (DBM) shows higher wing-vein injury than chlorpyrifos-susceptible (Sm) DBM under heat stress in our previous study. To investigate the toxicological mechanisms of the differences in injury of wing vein between Rc- and Sm-DBM collected from Fuzhou, China, total ten cDNA sequences of wing-development-related genes were isolated and characterized in DBM, including seven open reading frame (ORF) (ash1, ah2, ash3, ase, dpp, srf and dll encoded 187 amino acids, 231 aa, 223aa, 397aa, 423aa, 229aa and 299aa, respectively), and three partly sequences (salm, ser and wnt-1 encoded 614aa, 369aa and 388aa, respectively). The mRNA expression of the genes was inhibited in Rc- and Sm-DBM under heat stress, as compared with that an average temperature (25 °C). And, in general, significantly higher down-regulated expressions of the mRNA expression of the wing development-related genes were found in Rc-DBM as compared to those in Sm-DBM under heat stress. The results indicated that Sm-DBM displayed higher adaptability at high temperature because of significantly lower inhibition the mRNA expressions of wing-development-related genes. We suggest that significantly higher injury of wing vein showed in Rc-DBM under heat stress might be associated with the strong down-regulation of wing-development-related genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Insects are so numerous and widely distributed in nature because of their wings. The insect wing veins are not only an extraordinary skeleton to support wing, but also contains a catheter, a vascular gap and a nerve tissue1. The mechanism of insect wing-development pattern has mainly been focused in the biological model, Drosophila melanogaster. The formation of Drosophila wings consists of three cascade control pathways, i.e., anterior-posterior (A-P), dorsal-ventral (D-V), proximal-distal (P-D)2. The cascade control pathways determined the differentiation of the A-P, D-V and P-D in the wing disc by the expression of related genes, such as engrailed (en), apterous (ap), arista-less and other genes3,4. Thus the differentiation of the A-P is determined by the selective expression of engrailed (en) and the concentration gradient of decapentaplegic (dpp) protein5,6,7 in the wing disc. Development of D-V is determined by the selective expression of AP gene and the concentration gradient of the wingless (wg) protein8,9. And the base of the wing should develop into the distal wing lobe and the proximal middle thoracic dorsal plate, which is determined by the P-D10,11. As transcription factors, decapentaplegic (dpp), spalt-major-like (salm), serum response factor (srf) and wingless (wg), serrste (ser) and achaete-scute complex (As-c), Distal-less (dll) were involved in the three pathway8,12,13,14.

The gene regulation pathway in the development of the wing veins is highly conserved among insects15,16,17. Both wg and wnt are the homeotic genes18, and wnt plays an essential role in signaling pathways in the insect19,20,21. Wg is a morphological element, and the expression of the target gene is regulated by its concentration22,23,24. If the wg is missing, wing leaf and hinge area cannot be formed25. As-c is a family gene and contains the domain of basic Helix-loop-helix (BHLH)26. The function of this domain is to regulate the development of peripheral nervous system27, the precursor form of external sensory organs28, wing scales and insect sensory bristles29 and achaete-scute complex30. In existing reports, the Bombyx mori contains 4 AS-c genes (ash1, ash2, ash3, ase)31. While Butterflies, Culicidae, Apis mellifera, and Tribolium castaneum also have AS-c genes. Salm is a kind of gene which encodes C2H2 zinc finger protein and unique functional domain Znf is contained in salm32. During the development of insect wings, it controls the formation of the wing veins23,the formation of the bronchial system33 and wing imaginal disc24. Dpp is a morphological element. If the dpp is missing, it causes the adult to produce small wings, and salm will not express13. dll plays a role in larval and adult appendage development. Shape and size of adult wings were determined by dll16,34,35. Also, it has a secondary role in the normal patterning of the wing margin16,36. Ser control expression of cut and wg37,38. And srf is required for the formation of inter-vein tissue of the wing39,40. The functions of wing-development-related genes, WG in Sogatella furcifera41 and AS-C in Bombyx mori30, were proved in the development of the wings based RNAi method. However, no literature can be found to confirm the function of wing-development-related genes in DBM, including using RNAi method.It was known that wing development of insects would be very important for insect’s biological and physiological traits and their behavior, such as migration42. The effect of temperature on the development of insect wings is also reported, wing sizes and shapes in Drosophila can be affected by temperatures43. Previous studies explored that temperature affects the size and shape of the wings44,45,46. Our previous studies provided firstly the proof that wing development of DBM affected by pesticides resistance, i.e.high-temperature experienced in pupal stage influenced the phenotype of wing venation in insecticide-resistant (Rc) and insecticide-susceptible (Sm) P. xylostella. While, Sm-DBM showed significantly higher thermal tolerance and lower damages of wing veins under heat stress than Rc-DBM47. The expression of the caspase-7 gene (as an essential marker of apoptosis) in Rc-DBM were significantly higher than that of Sm strains under heat stress, on the other hand, the induced responses of hsp70s (as an essential protected protein) in Sm-DBM were significantly higher than those in Rc-DBM48,49,50. Rc-DBM showed significantly lower fitness in hermotolerance, oxidative stress, apoptosis, heat-shock proteins and damages to reproductive cells, as compared to Sm-DBM50.

The facts suggest that higher heat tolerance and lower damages of veins in susceptible DBM might be associated with their significantly lower apoptosis gene-expression and higher hsp70 gene-expression under heat stress. However, the expression of wing-development-related-genes was unknown. Therefore, ten key genes in insect wing development pattern that control the development of wing and mRNA expression of the wing-development-genes of Rc- and Sm- P. xylostella under heat stress was studied in the present study.

Results

Cloning and sequencing analysis of wing development-related genes

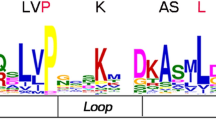

Based on the initial fragment sequence, the 3′- and 5′-end fragment were obtained by 3′- and 5′-RACE, respectively. Six full-length cDNA sequences (873; 809; 1012; 1799; 1891 and 949 bp for ash1; ash2; ash3; ase; dpp and srf, respectively) and four partial cDNA sequences (1541; 1885; 1196 and 1213 bp for dll; salm; ser and wntl, respectively) of wing development-related genes from DBM were gained by editing and splicing the cloned sequence (Table 1). The ORF sequence was 564 bp of ash1 (67–630 bp), 696 bp of ash2 (62–757 bp), 672 bp of ash3 (117–788 bp), 1194 bp of ase (144–1337 bp), 1272 bp of dpp (342–1613), 690 bp of srf (20–709 bp). The open reading frame (ORF) of the ash1, ah2, ash3, ase encodes 187, 231, 223 and 397 amino acids, respectively, and analysis showed that all of them contain HLH domain (55–116, 77–140, 68–131 and 98–162 aa, respectively). The ORF of dpp encodes 423aa that contain DWA and DWB domain (39–148aa and 227–399aa, respectively). The ORF of srf encodes 229aa that contain MADS domain (56–115aa). The four partial cDNA sequences (dll, salm, ser and wntl) encodes 299, 614, 369 and 388 aa, respectively (Table 2). Functional domain analysis of these amino acid sequences (dll, salm, ser, wntl), the HOX (129–191 aa), ZnF_C2H2 (86–108, 114–136, 431–453, 459–481 and 491–513 aa), Coiled-coil (105–135 aa) and wntl (56–388 aa) domain were found respectively (Tables 1 and 2, Figs 1–7 and S1–S10).

The phylogenetic analysis of achaete-scute homologue (ASH1, ASH2, ASH3, ASE) in DBM and other insects. Plutella xylostella ASE (AIZ67915.1); Operophtera brumata ASE (KOB69271.1); Bombyx mori ASE (NP_001098696.1); Danaus plexippus ASE (OWR43026.1); Anoplophora glabripennis ASC (XP_023310751.1); Drosophila erecta ASE (XP_001982390.1); Tribolium castaneum ASC (NP_001034537.1); Aedes aegypti ASC (XP_021712495.1); Plutella xylostella ASH1 (AIZ67914.1); Danaus plexippus ASH1 (OWR43025.1); Bombyx mori ASH1 (NP_001037416.1); Pieris rapae ASC (XP_022115666.1); Bombyx mori ASH2 (NP_001098692.1); Operophtera brumata ASH2 (KOB67667.1); Plutella xylostella ASH2 (AIZ67913.1); Bombyx mori ASH3 (NP_001098694.1); Plutella xylostella ASH3 (ALC76152.1); Danaus plexippus ASH3 (OWR43023.1); Operophtera brumata ASH3 (KOB69293.1).

The phylogenetic analysis of Dpp in DBM and other insects. Plutella xylostella (ALC76150.2); Pieris rapae (XP_022119285.1); Danaus plexippus (OWR47416.1); Bombyx mori (XP_004929407.1); Aedes aegypti (XP_021701909.1); Trichogramma pretiosum (XP_014230775.1); Drosophila hydei (XP_023170520.1); Onthophagus taurus (XP_022902496.1); Episyrphus balteatus (AEI25993.1); Leptinotarsa decemlineata (XP_023029182.1); Copidosoma floridanum (XP_014211661.1); Ceratitis capitata (XP_004530256.1); Tribolium castaneum (KYB26902.1); Bombus terrestris (XP_003394971.1).

The phylogenetic analysis of SRF in DBM and other insects. Plutella xylostella (AIZ67912.1); Papilio xuthus (XP_013173375.1); Onthophagus taurus (XP 022907989.1); Aethina tumida (XP 019871043.1); Musca domestica (XP 011294945.1); Aedes albopictus (XP 019562715.1); Pieris rapae (XP 022115280.1); Danaus plexippus (OWR41122.1); Papilio machaon (XP 014357061.1); Heliothis virescens (PCG72703.1); Helicoverpa armigera (XP 021190114.1); Spodoptera litura (XP 022828228.1).

The phylogenetic analysis of dll in DBM and other insects. Bicyclus anynana (AAL69325.1); Pieris rapae (XP_022120979.1); Bombyx mori (XP_012551909.1); Manduca sexta (AAT39558.1); Vanessa cardui (AJS19035.1); Papilio machaon (KPJ10995.1); Danaus plexippus (OWR43046.1); Papilio xuthus (KPI96576.1); Aedes aegypti (XP_021698712.1); Lucilia cuprina (KNC21963.1); Drosophila melanogaster (NP_726486.1); Ceratitis capitata (XP_012161414.1).

The phylogenetic analysis of salm in DBM and other insects. Plutella xylostella (ALC76153.2); Danaus plexippus (OWR44146.1); Operophtera brumata (KOB70391.1); Bombyx mori (XP_012549950.1); Pieris rapae (XP_022112446.1); Helicoverpa armigera (XP_021184031.1); Spodoptera litura (XP_022820679.1); Leptinotarsa decemlineata (XP_023026015.1); Lasius niger (KMR01384.1); Trichogramma pretiosum (XP_023316968.1); Athalia rosae (XP_020709204.1); Acromyrmex echinatior (EGI68679.1); Atta colombica (KYM93127.1).

The phylogenetic analysis of ser in DBM and other insects. Spodoptera litura (XP_022821559.1); Pieris rapae (XP_022130556.1); Helicoverpa armigera (XP_021188794.1); Bombyx mori (XP_012549285.1); Papilio machaon (KPJ16753.1); Cryptotermes secundus (PNF27227.1); Dufourea novaeangliae (KZC14437.1); Bombus terrestris (XP_003399363.1); Habropoda laboriosa (KOC62545.1); Pseudomyrmex gracilis (XP_020288292.1); Melipona quadrifasciata (KOX79304.1); Copidosoma floridanum (XP_014211886.1).

The phylogenetic analysis of wnt-1 in DBM and other insects. Plutella xylostella (ALC76151.1); Spodoptera litura (XP_022820536.1); Pieris rapae (XP_022116444.1); Bombyx mori (NP_001037315.1); Papilio xuthus (KPI94016.1); Aedes aegypti (XP_021702999.1); Copidosoma floridanum (XP_014212755.1); Orussus abietinus (XP_012289230.1); Bombus terrestris (XP_003393164.1); Apis cerana (PBC26820.1); Cyphomyrmex costatus (KYN01512.1); Atta colombica (KYM88337.1).

According to the Blast results, the higher homogeneities of amino acids in the wing development-related genes with other insects were as follows. ash1 had presented 78, 79, 79 and 81 percent with Bombyx mori (NP_001037416), Danaus plexippus (OWR43025), Helicoverpa armigera (XP_021183890) and Spodoptera litura (XP_022829400.1), respectively (Fig. S1). ash2 had exhibited 85, 84 and 83 percent with B. mori (NP_001098692), S. litura (XP_022829477), and H. armigera (XP_021183904), respectively (Fig. S2). ash3 had shown 68, 62 and 61 percent with B. mori (NP_001098694), D. plexippus (OWR43023) and Operophtera brumata (KOB69293), respectively (Fig. S3). ase had depicted 72, 70, 68 and 66 percent with Pieris rapae (XP_022115661), H. armigera (XP_021183923), D. plexippus (OWR43026) and B. mori (NP_001098696), respectively (Fig. S4). dpp had illustrated 98, 98, 82 and 81 percent with B. mori (XP_004929407), D. plexippus (OWR47416), Drosophila melanogaster (NP_001259992) and Lasius niger (KMQ88665), respectively (Fig. S5). Similarly, srf had demonstrated 92, 92, 91, 90 and 68 percent with H. armigera (XP_021190114), S. litura (XP_022828228), P. rapae (XP_022115280), B. mori (XP_012552250) and Tribolium castaneum (NP_001139383), respectively (Fig. S6). Likewise, dll had shown 95, 94, 93, 90 and 60 percent with Manduca sexta (AAT39558), Vanessa cardui (AJS19035), P. rapae (XP_022120979), B. mori (XP_012551909) and D. melanogaster (NP_726486), respectively (Fig. S7). salm had given 83, 82, 82, 69 and 67 percent with O. brumata (KOB70391), D. plexippus (OWR44146), P. rapae (XP_022112446), B. mori (XP_012549950) and H. armigera (XP_021184031), respectively (Fig. S8). ser had shown 74, 73, 73, 73, 72 and 38 percent with H. armigera (XP_021188794), P. rapae (XP_022130556), S. litura (XP_022821559), Papilio machaon (KPJ16753), B. mori (XP_012549285) and Cryptotermes secundus (PNF27227), respectively (Fig. S9). wnt-1 had presented 88, 87, 82 and 81 percent with P. rapae (XP_022116444), S. litura (XP_022820536), Papilio xuthus (KPI94016) and B. mori (NP_001037315), respectively (Fig. S10). Phylogenetic analysis revealed that wing-development-related genes from P. xylostella were clustered together with other Lepidoptera insects (Figs 1–7).

Expressions of wing-development-related genes under heat stress in pupae

In general, as compared to 25 °C, the mRNA expression levels of ash2, ash3, ase, srf were significantly down-regulated both in Sm- and Rc-pupae under heat stress, and non-significant differences were observed between Sm- and Rc-strain, whereas significantly down-regulated at 42 °C for 4 or 8 h in ash3, at 42 °C for 8 h and 40 °C for 10 h in ase and at 42 °C for 4 and 8 h and 40 °C for 8 and 16 h in srf were found in Rc- strain, as compared to those in Sm-strain (Fig. 8). Although Sm- and Rc-pupae displayed the same level of mRNA expression of wnt-1 in all groups, heat stress resulted in significantly down-regulated expression of wnt-1 in Rc- pupae (Fig. 8). Sm- and Rc-pupae showed similar level of mRNA expression of ash1 at 25 °C in all group, however, significant higher down-regulated expressions of ash1 were found in Rc-pupae at 42 °C for 4 or 8 h, 40 °C for 8 or 16 h and 38 °C for 48 h (Fig. 8). Rc-pupae showed significantly down-regulation mRNA expression of dpp and salm in almost all of the heat stress groups (Fig. 8). Rc-pupae displayed the significantly lower expressions of dll and ser at 42 °C for 4 or 8 h, 40 °C for 8 or 16 h and 38 °C for 48 h (Fig. 8). In general, Rc-pupae displayed significantly lower expression of mRNA than Sm-pupae under heat stress for the wing-development-related genes under heat stress in the the groups, and no significant differences in basal (at 25 °C) expression of most genes between Sm- and Rc-pupae (Fig. 8).

Effects of heat stress on the expression of wnt-1, ash1, ash2, ash3, ase, dll and dpp, srf, salm ser in Rc (black) and Sm (white) pupa DBM. Abscissa: temperature (°C)-treated time (h). Ordinate: relative quantity expression of the genes. Pupae newly formed at 25 °C from both Rc and Sm populations were incubated by four temperature treatments, that is, 25 or 44 °C for 1 h (25–1 or 44–1), 25 or 40 °C for 8 (25–8 or 40–8) or 16 h (40–16), 25 or 42 °C for 4 (25–4 or 42–4) or 8 h (42–8), and 25 or 38 °C for 48 h (25–48 or 38–48), respectively. Living pupae after heat stress were allowed to recovery for 1 h at 25 °C before they were used for extracting mRNA. The values in each group of the four temperature treatments were used for statistical analysis, respectively, in Rc and Sm DBM. Lower-case letter indicates significant difference in mRNA expression in each temperature treatment group (Duncan test, P ≤ 0.05).

There was a distinct feature in the group of (25 °C-16h, 40 °C for 8 h and 16 h) that most genes (ase, dll, srf, dpp) were well expressed in Sm-strain under heat stress, especially at 40 °C (for 8 h or 16 h). Rc- pupae displayed significantly lower expression of mRNA than Sm-pupae under heat stress at 40 °C (Fig. 8).

In the group of (25 °C-48h; 38 °C-48h), all wing-development-related genes showed lower mRNA expressions level than other groups, except ser. And most of them showed the same pattern that is Rc-pupae showed significantly lower expression of mRNA than Sm-pupae under heat stress, but interestingly, the same pattern also happens in 25 °C, that is different from other groups (Fig. 8).

Discussion

In the present study, ten cDNA sequences of wing-development-related genes were identified from the diamondback moth, P. xylostella. The results of amino acid sequence alignment showed that the ash1, ash2, ash3, ase, dpp, srf, dll, salm, ser and wnt-1 protein of P. xylostella was similar to the homologous protein in other species. Because DBM belongs to Lepidoptera, the amino acid sequence of P. xylostella was compared with that of another Lepidopteran insect, B. mori. Analysis of amino acid sequences homogeneity between P. xylostella and B. mori had shown 66–98 percent similarity, higher conservation in the structural domain. In addition, the phylogenetic analysis revealed that wing-development-related genes from P. xylostella were clustered together with other Lepidopteran insects. The above analysis confirms that the obtained gene sequences are our target genes.

In general, based on the selected Rc- and Sm-DBM pupae, significant inhibitions of mRNA expression (down-regulation of wing-development-related genes) were found in all of the wing-development-related genes in both Sm and/or Rc-DBM pupae under heat stress including at 40 °C, 42 °C, 44 °C and/or 38 °C treatments, although there were several exceptions. Although no significant differences in basal expression (at 25 °C) of most genes between Sm- and Rc-pupae, significantly higher inhibitions on the mRNA expression of the genes were found in Rc-DBM in many cases.

The fitness cost in resistant insect species is a general tendency and found in many insect species51. Insecticide-resistant insects showed significant fitness cost in life-history, behavior and physiological traits48. However, the researches were carried out under a suitable temperature48. In our previous study, it was confirmed that insecticide-resistant DBM showed significant fitness cost under heat stress. Rc-DBM showed significantly lower fitness under heat stress in hermotolerance, fecundity, oxidative stress, apoptosis, heat-shock proteins and damages to reproductive cells, as compared to Sm-DBM47,48,49,50. In addition, higher wing-vein injury under heat stress in Rc-DBM was found as compared to that in Sm-DBM47. It was the first evidence of morphogenesis as the fitness cost caused by insecticide resistance in insects. However, the mechanisms should be investigated.

The present study was aimed to study the effects of high temperature on the mRNA expression of the wing development-related genes in insecticide-resistant and –susceptible DBM. Rc- or Sm-DBM pupae strains were reared and collected for temperature treatments at the same time. The results obtained in present study indicated that heat stress would resulted in significantly higher inhibitions on the mRNA expressions of wing development-related genes in Rc-DBM pupae strains, and significant fitness costs were existed in Rc-DBM pupae trains. Significantly higher inhibitions on mRNA expression of the wing development-related genes under heat stress in Rc-DBM was confirm firstly. The results indicated that higher damage in development of wing veins in Rc-DBM under heat stress47 might be associated with significantly higher inhibitions on the mRNA expressions of wing development-related genes. The fitness cost in resistant DBM in our previous studies47,48,49,50 and in the present study might be linked partly to the resistant alleles ace1R – the allele conferring the resistance to several to several OP insecticides48. Although the mRNA expression of the genes was studied by qPCR in present study, the RNAi of the genes should be conducted to study the functions of the genes in our future study.

The wing development of insects would be very important for insect’s evolution and adaptability to environment30. It would be important that when designing insect management program, fitness cost caused by insecticide resistance should be considered to maximize the effect of insecticides and minimize costs and residues of controlling insects.

Methods

Sources of insects

Resistant and Sensitive strains of DBM were long-term reared in our laboratory. The Sm-strain is the most sensitive to chlorpyrifos whereas Rc-strain is highly resistant to this insecticide. These strains were gained from a population collected from Shangjie (34°480 N, 113°180E) (Fuzhou, Fujian, China). Details of the selection of these two strains are provided elsewhere50. No specific permissions were required for our collection of P. xylostella, because the scientists were welcome to collect the insect sample from the farmer’s crucifer fields in order to control the pest insects. The field studies did not involve endangered or protected species.

Cloning wing development-related genes

Fourth instar larvae of Sm-DBM were selected and reared at 25 °C temperature. Then on the third day, F1 progenies were used for the total RNA extraction.

Amplification of the initial fragments of wing development-related genes

Total RNAs were extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions for the MiniBEST Universal RNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa Bio Inc.). First-strand cDNAs were synthesized from 5 μg of total RNAs using PrimeScript™ II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa Bio Inc.). For amplification of the initial fragments of wing development-related genes, specific primers were designed (Table 3). PCR conditions were as follows; 94 °C denaturation for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, an annealing step at 52 °C (52 °C for dll; 54 °C for ash1, ash3, ase, ser; 55 °C for ash2; 56.5 °C for salm; 57 °C for srf; 59.5 °C for dpp; 61 °C for wnt-l) for 1–2 min, an extension step at 72 °C for 2–3 min, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 7–10 min.

Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) of wing development-related genes

For 3′- and 5′-RACE, the first-strand cDNAs were separately constructed from 1 μg of total RNA according to the SMARTer® RACE 5′/3′ Kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.). According to the cloned intermediate target gene fragment and the nested PCR principle, 3′- and 5′-RACE specific primers were designed by using Primer 5.0 software, respectively (Table 3). PCR Program was set as follows; 94 °C for 3 min; 94 °C 30 sec, 68 °C 30 sec, 72 °C 3 min for 25 cycles, and 72 °C for 7 min.

Amplification of ORFs

To identify the edited full-length sequences, ORFs were amplified by using forward and reverse primers corresponding to the 5′ and 3′-ends of the full-length sequences, respectively (Table 3). PCR conditions were 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 sec, 52 °C (52 °C for ash1, 55 °C for ash2, 47 °C for ash3, 52 °C for ase, 55 °C for dpp, 57 °C for srf) for 30 sec, and 72 °C for 1–2 min, finally 72 °C for 7–10 min. The initial fragments, 3′- and 5′-RACE fragments and the ORF fragments were cloned and sequenced by Shanghai Biosune Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Temperature shock

According to the previous study of Zhang et al.47, the pupae were grouped into four groups and treated with heat stress at four different temperatures, i.e., 38 °C for 48 h; 40 °C for 8 h and 16 h; 42 °C for 4 h and 8 h, and 44 °C for 1 h, whereas the control group was maintained at 25 °C in the four groups, respectively. After heat stress, the pupae were allowed to recover for 1 h at 25 °C, before being used for detecting mRNA expression.

Determination of mRNA expression

After RNA extraction, cDNAs were synthesized from 0.5 μg of total RNAs using PrimeScriptTMRT reagent Kit (TaKaRa Bio Inc.). The primers used for qPCR of these genes are listed in Table 4, while the primers for β-actin (house-keeping gene) were used as the endogenous control. qPCR was executed using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System (AB, Life Technologies) with SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ (TaKaRa Bio Inc.), and conditions were set as following: 95 °C for 30 sec; 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 sec, 60 °C for 34 sec; Melt Curve: 95 °C for 15 sec, 60 °C for 1 min, and 95 °C for 15 sec. The homogeneity of the PCR products was confirmed by melting curve analysis. The expression level of each gene was calculated according to the threshold cycle (CT) and the relative expression was calculated using the Livak method (2(−ΔΔCt))52. Thus, the normalized expression value of the target gene was calculated by comparing the expression value of the target gene with β-actin49. All data obtained from qPCR were analyzed using the Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS). Three biological replications, with ten insect individuals for each replication, were used in the expression of mRNA.

Phylogenetic tree analyses

The phylogenetic analysis of achaete-scute homologue in DBM and other insect was carried out by using the maximum likelihood method (MEGA 6.0).

Statistical analysis

The data of mRNA expression were analyzed by probit analysis53 using a DPS data processing system54.

References

Lewin, R. On the Origin of Insect Wings: Experimental data on thermoregulation and aerodynamics give the first quantitative test of a popular hypothesis for the evolution of flight in insects. Science. 230, 428–9 (1985).

Babu, P. Early developmental subdivisions of the wing disk in Drosophila. Mol. Gen. Genet. 151, 289–94 (1997).

Posakony, L. G., Raftery, L. A. & Gelbart, W. M. Wing formation in Drosophila melanogaster requires decapentaplegic gene function along the anterior-posterior compartment boundary. Mech. Dev. 33, 69–82 (1990).

Klein, T. & Arias, A. M. Different spatial and temporal interactions between Notch, wingless, and vestigial specify proximal and distal pattern elements of the wing in. Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 194, 196–212 (1998).

Sui, L., Pflugfelder, G. O. & Shen, J. The Dorsocross T-box transcrip-tion factors promote tissue morphogenesis in the Drosophila wing imaginal disc. Development. 139, 2773–2782 (2012).

Raftery, L. A., Sanicola, M., Blackman, R. K. & Gelbart, W. M. The relationship of decapentaplegic and engrailed expression in Drosophila imaginal disks: do these genes mark the anterior-posterior compartment boundary. Development. 113, 27–33 (1991).

Guillen, I. et al. The function of engrailed and the specification of Drosophila wing pattern. Development. 121, 3447 (1995).

Baena-Lopez, L. A., Franch-Marro, X. & Vincent, J. P. Wingless promotes proliferative growth in a gradient-independent manner. Sci. Signaling. 2, ra60 (2009).

Franchmarro, X. et al. Wingless secretion requires endosome-to-Golgi retrieval of Wntless/Evi/Sprinter by the retromer complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 170–7 (2008).

Cifuentes, F. J. & Garcíabellido, A. Proximo-distal specification in the wing disc of Drosophila by the nubbin gene. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 11405–10 (1997).

Klein, T. Wing disc development in the fly: the early stages. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 11, 470–5 (2001).

Strigini, M. & Cohen, S. M. A Hedgehog activity gradient contributes to AP axial patterning of the Drosophila wing. Development. 124, 4697 (1997).

Sekelsky, J. J., Newfeld, S. J., Raftery, L. A., Chartoff, E. H. & Gelbart, W. M. Genetic characterization and cloning of mothers against dpp, a gene required for decapentaplegic function in Drosophila melanogaster. Genet. 139, 1347 (1995).

Weatherbee, S. D., Halder, G., Kim, J., Hudson, A. & Carroll, S. Ultrabithorax regulates genes at several levels of the wing-patterning hierarchy to shape the development of the Drosophila haltere. Gene.Dev. 12, 1474–1482 (1998).

Lewis, E. B. A gene complex controlling segmentation in Drosophila. Nature 276, 565 (1978).

Campbell, G. & Tomlinson, A. The roles of the homeobox genes aristaless and Distal-less in patterning the legs and wings of Drosophila. Developmrnt. 125, 4483 (1998).

Kusserow, A. et al. Unexpected complexity of the Wnt gene family in a sea anemone. Nature. 433, 156–60 (2005).

Rijsewijk, F. et al. The Drosophila homology of the mouse mammary oncogene int-1 is identical to the segment polarity gene wingless. Cell. 5, 649–657 (1987).

Larsen, C. & Bardet PLVincent, J. P. Specification and positioning of parasegment grooves in. Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 321, 310–8 (2008).

Tong, X., Lindemann, A. & Monteiro, A. Differential Involvement of Hedgehog Signaling in Butterfly Wing and Eyespot Development. Plos One. 7, e51087–e51087 (2012).

French, V. & Brakefield, P. M. Pattern formation: a focus on notch in butterfly eyespots. Curr. Biol. 14, 663–665 (2004).

Wagner-bernholz,Wilson, C., Gibson, G., Schuh, R. & Gehring, W.J. Identification of target genes of the homeotic gene Antennapedia by enhancer detection. Gene. Dev. 5, 2467 (1991).

Schwank, G., Restrepo, S. & Basler, K. Growth regulation by Dpp: an essential role for Brinker and a non-essential role for graded signaling levels. Development. 135, 4003–13 (2008).

Grieder, N. C. et al. Spalt major controls the development of the notum and of wing hinge primordia of the Drosophila melanogaster wing imaginal disc. Dev. Biol. 329, 315–326 (2009).

Port, F. et al. Wingless secretion promotes and requires retromer-dependent cycling of Wntless. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 178 (2008).

Cau, E. & Wilson, S. W. Ash1a and neurogenin1 function downstream of Floating head to regulate epiphysial neurogenesis. Development. 130, 2455–66 (2003).

Skaer, N., Lio, P., Wulbeck, C. & Simpson, P. Gene duplication at the achaete-scute complex and morphological complexity of the peripheral nervous system in Diptera. Trend. Genet.Tig. 18, 399–405 (2002).

Wulbeck, C. & Simpson, P. Expression of achaete-scute homologues in discrete proneural clusters on the developing notum of the medfly Ceratitis capitata, suggests a common origin for the stereotyped bristle patterns of higher Diptera. Development. 127, 1411 (2000).

Galant, R., Skeath, J. B., Paddock, S., Lewis, D. L. & Carroll, S. B. Expression pattern of a butterfly achaete-scute homolog reveals the homology of butterfly wing scales and insect sensory bristles. Curr. Biol. Cb 8, 807 (1998).

Tong, X. L. et al. Identification and expression of the achaete-scute complex in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Mol. Biol. 17, 395–404 (2010).

Knöll, B. & Nordheim, A. Functional versatility of transcription factors in the nervous system: the SRF paradigm. Trends Neurosc. 32, 432–442 (2009).

Kühnlein, R. P. et al. spalt encodes an evolutionarily conserved zinc finger protein of novel structure which provides homeotic gene function in the head and tail region of the Drosophila embryo. EMBO J. 13, 168–79 (1994).

Franchmarro, X. & Casanova, J. spalt-induced specification of distinct dorsal and ventral domains is required for Drosophila tracheal patterning. Dev. Biol. 250, 374 (2002).

Azpiazu, N. & Morata, G. Function and regulation of homothorax in the wing imaginal disc of Drosophila. Development. 127, 2685–93 (2000).

Casares, F. & Mann, R.S. A dual role for homothorax in inhibiting wing blade development and specifying proximal wing identities in Drosophila. Development. 127, 1499–1508.

Gorfinkiel, N., Morata, G. & Guerrero, I. The homeobox gene Distal-less induces ventral appendage development in Drosophila. Gene. Devel. 11, 2259–71 (1997).

Thomas, U., Speicher, S. A. & Knust, E. The Drosophila gene Serrate encodes an EGF-like transmembrane protein with a complex expression pattern in embryos and wing discs. Development. 111, 749 (1991).

Micchelli, C. A., Rulifson, E. J. & Blair, S. S. The function and regulation of cut expression on the wing margin of Drosophila: Notch, Wingless and a dominant negative role for Delta and Serrate. Deelopmentv. 124, 1485–95 (1997).

Affolter, M. et al. TheDrosophila SRF homolog is expressed in a subset of tracheal cells and maps within a genomic region required for tracheal development. Development. 120, 743–53 (1994).

Montagne, J. et al. The Drosophila Serum Response Factor gene is required for the formation of intervein tissue of the wing and is allelic to blistered. Development. 122, 2589–2597 (1996).

Yu, J. L., An, Z. F. & Liu, X. D. Wingless gene cloning and its role in manipulating the wing dimorphism in the white-backed planthopper, Sogatella furcifera. BMC Mol. Biol. 15, 20 (2014).

Frank, J. F., Soderquist, M. & Bokma, F. Insect wing shape evolution: independent effects of migratory and mate guarding flight on dragonfly wings. Biol. J. Linnean Society. 97, 362–372 (2009).

Debat, V., Debelle, A. & Dworkin, A. I. Plasticity, canalization, and developmental stability of the Dtosophila wing: Joint effects of mutations and developmental temperature. Evolution 63, 1558–5646 (2009).

Røgilds, A., Andersen, D. H., Pertoldi, C., Dimitrov, K. & Loeschck, V. Maternal and grandmaternal age effects on developmental instability and wing size in parthenogenetic Drosophila mercatorum. Biogerontology 6, 61–9 (2015).

Loeschcke, V., Kjaersgaard, A., Pertoldi, C. & Loeschcke, V. The effect of maternal and grandmaternal age in benign and high temperature environments. Exp. Gerontol. 40, 988–996 (2005).

Kjærsgaard, A. et al. Effects of temperature and maternal and grandmaternal age on wing shape in parthenogenetic Drosophila mercatorum. J. Therm. Biol. 32, 59–65 (2007).

Zhang, L. J. et al. Trade‐off between thermal tolerance and insecticide resistance in Plutella xylostella. Ecol. Evol. 5, 515 (2015).

Zhang, L. J. et al. Temperature-sensitive fitness cost of insecticide re-sistance in Chinese populations of the diamondback moth Plutella xylostella. Mol. Ecol. 24, 1611–1627 (2015).

Zhang, L. J., Wang, K. F., Jing, Y. P., Zhuang, H. M. & Wu, G. Identification of heat shock protein genes hsp70s and hsc70 and their associated mRNA expression under heat stress in insecticide-resistant and susceptible diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Eur. J. Entomol. 112, 215–226 (2015).

Zhang, L. J. et al. Thermotolerance, oxidative stress, apoptosis, heat-shock proteins and damages to reproductive cells of insecticide-susceptible and -resistant strains of the diamondback moth Plutella xylostella. Bull. Entomol. Res. 107, 513–526 (2017).

Kliot, A. & Ghanim, M. Fitness costs associated with insecticide resistance. Pest Manag. Sci. 68, 1431–1437 (2012).

Schmittgen, T. D. & Livak, K. J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. protoc. 3, 1101–1108 (2008).

Finney, D.J. Probit, analysis. Cambridge University Press, London, United Kingdom. (1971).

Tang, Q. & Feng, M. G. Practical Statistics and DPS Data Processing System. In: DPS Data Processing System for Practical Statistics (edited by Tang, Q. Y. & Feng, M. G.) Beijing, China, 188–195 (China Agricultural Press,1997).

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NNSFC) (31272049) and Key foundation of technology project of Fujian Province (2014N0003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.W. conceived the experiments, analyzed the data, generated the tables, produced the figures and wrote the manuscript. X.Z.C., Q.X.H., Q.Q.L. and G.W. Performed the experiments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X.Z., Hu, Q.X., Liu, Q.Q. et al. Cloning of Wing-Development-Related Genes and mRNA Expression Under Heat Stress in Chlorpyrifos-Resistant and -Susceptible Plutella xylostella. Sci Rep 8, 15279 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33315-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33315-z

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.