Abstract

Freshwater eels of the genus Anguilla comprise 16 species that include three subspecies and are characterized by their unique catadromous life cycles. Their life histories and nocturnal life styles make it difficult to observe them in freshwater and marine habitats. To investigate their distribution and ecology in aquatic environments, we developed new PCR primers for metabarcoding environmental DNA (eDNA) from Anguilla. The new primers (MiEel) were designed for two conserved regions of the mitochondrial ATP6 gene, which amplify a variable region with sufficient interspecific variations ranging from five to 22 nucleotide differences (one to three nucleotide differences between three subspecies pairs). We confirmed the versatility of the MiEel primers for all freshwater eels using tissue DNA extracts when analyzed separately. The metabarcoding combined with the MiEel primers using mock communities enabled simultaneous detection of Anguilla at the species level. Analysis of eDNA samples from aquarium tanks, a controlled pond and natural rivers demonstrated that the MiEel metabarcoding could successfully detect the correct Anguilla species from water samples. These results suggested that eDNA metabarcoding with MiEel primers would be useful for non-invasively monitoring the presence of the endangered anguillid eels in aquatic environments where sampling surveys are difficult.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Environmental DNA (eDNA) can be extracted from environmental samples such as soil, water or air without isolating any target species1. Aquatic organisms release various quantities of eDNA through metabolic waste, damaged tissue, or sloughed skin cells in their environments2. Ficetola et al.3 was the first study to present an eDNA analysis that could detect the American bull frog Lithobates catesbeianus as invasive species in controlled environments and natural wetlands. Subsequently, the eDNA analysis has been applied to the detection of a single or a few rare, endangered and closely related species in aquatic ecosystems3,4,5,6,7. Furthermore, eDNA analysis using high-throughput next-generation sequencing (NGS) has enabled simultaneous multiple-species identification from a single environmental sample, which has been called “eDNA metabarcoding”, in aquaria, mesocosms, natural rivers and coastal areas8,9,10. The efficiency of eDNA metabarcoding was comparatively better than or at least as good as conventional survey methods such as net sampling, snorkeling observation, and bottom trawling8,10,11. eDNA metabarcoding is non-invasive and is expected to be a sensitive, cost- and time-effective method to estimate the distribution and biodiversity of various aquatic organisms.

eDNA metabarcoding requires a genetic marker with suitable taxonomic resolution and an appropriate methodology using NGS. For example, Miya et al.9 developed universal PCR primers, named MiFish, with high fish taxonomic resolution and detected more than 230 subtropical marine fish species from aquarium tanks and coral reefs. Valentini et al.10 identified a maximum of 19 fish species from water samples using another set of universal primers developed by an ECOPRIMERS software (see ref.12). However, the eDNA metabarcoding studies using those developed universal primers that amplified short fragments within the 12S ribosomal RNA (12S rRNA) could not always distinguish all target species9,10. Indeed, eDNA metabarcoding using MiFish primers could not assign amplicon sequences to Sebastes spp, Takifugu spp13 and freshwater eels Anguilla (Fig. 1). The low taxonomic resolution in some target species resulted from highly similar sequences among closely related species and a lack of their sequences in the reference databases9,10,14.

Neighbor-joining tree of 19 species and subspecies the genus Anguilla plus Serrivomer beanii as an out-group based on the amplified regions of MiFish9 (12S rRNA) and MiEel (ATP6 gene). Distance was calculated using the Kimura two parameter model with all sequences containing gaps being eliminated, and numerals beside the internal branches are bootstrap probabilities of 300 replicates. This analysis of phylogenetic tree was conducted in MEGA635.

There is great concern about the conservation status of the catadromous freshwater eels of the genus Anguilla, which are one group of fishes that can be difficult to study using conventional sampling methods. Eel populations have dramatically declined in recent decades apparently due to multiple factors such as habitat loss, overexploitation and ocean-atmosphere changes15. Most Anguilla are now classified at various levels of concern by the IUCN Red List15,16. However, their life histories hamper their conservation and management. They are famous for their remarkable migrations between ocean spawning areas and freshwater growth habitats17. A survey in their oceanic spawning areas requires a research vessel, and major efforts to use large nets or trawls to collect their eggs, larvae and adults18,19. In freshwater, juveniles of A. anguilla and A. japonica spend most of their time hiding in refuges during daytime20,21. Telemetry tracking studies indicated that A. anguilla, A. australis, A. dieffenbachii, and A. rostrata were active mostly at night in river systems22,23,24. The remarkable migrations and fossorial life styles make it difficult to observe them in aquatic environments and monitor their presence or absence. A species-specific method to detect DNA from fish stomachs and eDNA has been already used for A. anguilla25,26 and A. japonica27 to begin to overcome these difficulties.

The aquatic environment suspends DNA source materials, enabling it to be sampled and detected even for species that are difficult to observe or collect4. Assuming that eDNA metabarcoding can effectively detect multiple species presence without visual observation, it will complement a monitoring in marine and freshwater habitats of all freshwater eels whose populations have rapidly decreased. The objective of this study was to develop new PCR primers at the species or subspecies level for eDNA metabarcoding of the genus Anguilla. Additionally, the performance of newly developed primers (herein referred to as MiEel) was tested using tissue-derived DNA extracts from 19 freshwater eels and eDNA samples from aquarium tanks, a controlled pond and natural rivers.

Methods

Primer design

For analysis of metabarcoding eDNA, new primers were designed following three requirements: (1) a target amplicon with less than 200 bp is desirable because the eDNA will often be degraded, (2) the amplified regions include sufficient interspecific differences for all target species and (3) conserved regions (20–30 bp) across all target species are located at both ends of the short variable regions to simultaneously amplify targeted sequences9,10,12. The search for a region that satisfied the above requirements was performed on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequences with a high copy number per cell. The complete mtDNA for 19 species and subspecies of the genus Anguilla (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession number AB038556, AP007233–AP007249, AB469437 from Minegishi et al.28,29) was used for the primer design. All the sequences were aligned using MAFFT v. 6.95630, and the aligned sequences were visually inspected with MESQUITE v. 2.7531 to locate the short variable region flanked by two conserved regions. Melting temperatures (Tm) of the designed primers were calculated using a nearest neighbor method implemented in OligoCalc, and G/C contents were also evaluated32.

A WebLogo33 was used to explore the similarity between the sequences of the newly designed primers and species of the anguilliforms including Anguilla. We downloaded whole mitogenome sequences of 19 other closely related anguilliforms that determined by Inoue et al.34 that conducted a phylogenetic analysis. The 19 sequences were registered specimens with voucher numbers in the DDBJ. To avoid wrong taxonomic assignment of sequences, we also calculated pairwise distances between Anguilla and the anguilliforms for the sequences that would be amplified by the MiEel primers using MEGA635.

Test of primers with extracted DNA

To examine whether the designed primers amplify the target regions for all freshwater eels, the performance was tested using extracted DNA from a single individual of each 19 species and subspecies of Anguilla. Total DNA was extracted from each tissue (muscle, liver or fin), that was preserved in 99% ethanol for more than 10 years, using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with an elution volume of 100 µl. Species identification of the tissue samples used in this study were carefully morphologically and genetically conducted previously36, which assured correct taxonomic assignment of sequences to each species of Anguilla. DNA concentrations were measured with a NanoDrop Lite spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, DE, USA), and the extracted DNA was diluted to 5 ng μl−1 using sterile distilled H2O. PCR was carried out with 30 cycles of a 7.67 µl reaction volume containing 2.29 µl of sterile distilled H2O, 3.82 µl of 2 × Gflex PCR buffer (Takara, Otsu, Japan), 0.38 µl of each primer (5 µM), 0.16 µl of Tks Gflex DNA polymerase (Takara, Otsu, Japan) and 0.64 µl of the diluted DNA extracts. The thermal cycle profile after an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 1 minute was as follows: denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 50 °C for 10 s and extension at 68 °C for 10 s with the final extension at the same temperature for 7 minutes. The PCR products were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gel (L03; Takara, Otsu, Japan) to check the amplifications. The PCR products were purified using Exo Sap-IT (USB, OH, USA) to remove redundant dNTPs, primers and nucleotides. Direct sequencing of the purified PCR products was performed with the ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Life Technologies, CA, USA) and dye-labelled terminators (BigDye terminator v. 1.1; Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). The DNA sequences were edited and assembled by GENETYX-MAC v. 17 (Genetyx, Tokyo, Japan) and registered in the DDBJ/EMBL/NCBI database (accession number LC198042–198060).

Library preparation and MiSeq sequencing with mock communities

To test whether the metabarcording approach using MiEel primers can distinguish the 19 species freshwater eels, six types of mock community were prepared using tissues-derived DNA extracts (diluted in 1.5 ml tubes to 5 ng μl−1) of different combinations of the Anguilla species. Six mock communities were subjected to the first-round PCR (1st PCR) and the second-round PCR (2nd PCR) in order to append amplified sequences with three kinds of adaptor sequence: (1) primer-binding sites for sequencing, (2) dual-index sequences to distinguish amplicons and (3) sequences for binding to the flowcells of the Illumina MiSeq (Illumina, CA, USA). The 1st PCR was carried out with 35 cycles of a 12 µl reaction volume containing 6.0 µl of 2 × KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (KAPA Biosystems, MA, USA), a final concentration of 0.3 µM of each MiEel primer, 2.6 µl of sterile distilled H2O and 2.0 µl of each mock community. The thermal cycle profile after an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 minutes was as follows: denaturation at 98 °C for 20 s, annealing at 65 °C for 15 s and extension at 72 °C for 15 s with the final extension at the same temperature for 5 minutes. The 1st PCR products were purified using a MinElute Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Subsequently, the purified products were quantified using TapeStation 2200 (Agilent, Tokyo, Japan), diluted to 0.1 ng µl−1 using sterile distilled H2O, and then used as a template for the 2nd PCR.

The 2nd PCR was conducted with 12 cycles of a 12 µl reaction volume containing 6.0 µl of 2 × KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix, 0.7 µl of each primer (5 µM), 3.6 µl of sterile distilled H2O and 1.0 µl of the template. Different combinations of dual-index sequences (chosen from A/D501−508 for forward primers and A/D701−712 for reverse primers from Miya et al.9) were used for different templates in the 2nd PCR. The thermal cycle profile after an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 minutes was as follows: denaturation at 98 °C for 20 s, annealing and extension combined at 72 °C (shuttle PCR) for 15 s with the final extension at the same temperature for 5 minutes. 1st PCR and 2nd PCR blanks were included with each PCR run to monitor contamination.

All the libraries containing the target regions and the three adapter sequences were mixed in equal volume, and the pooled libraries were size-selected from approximately 340 bp using 2% E-Gel Size Select agarose gel (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The concentration of the size-selected libraries was measured using a Qubit dsDNA HS assay Kit and a Qubit Fluorometer (Life Technologies, CA, USA). The libraries were sequenced on the Miseq platform using a MiSeq v2 Reagent Kit for 2 × 150 bp PE (Illumina, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Water sampling and filtration

An on-site filtration method developed by Miya et al.37 was employed to collect fresh eDNA. Disposable gloves were worn and changed between each sample. After collecting surface water using a bucket, the water was drawn into a disposable 50 ml syringe (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) and then pushed through a 0.45 µm Sterivex filter cartridge (Millipore, MA, USA). This step was repeated until 500 ml water volume was filtered. A RNAlater of 1.6 ml (Thermo Fisher Scientific, DE, USA) was added into the cartridge after the filtration to prevent eDNA degradation. The bucket was sterilized with 0.5% bleach and thoroughly prewashed with tap water or freshwater before reuse.

For aquarium tanks and a pond, water of 500 ml was filtered from each of two aquarium tanks (120 × 45 × 40 cm; water volume = 205 l) that each contained one species (A. bicolor bicolor, A. australis sp., respectively) on 22 August 2017. The total length of the two eels in each aquarium was approximately 70 cm. The two tanks were not sterilized because they were used as displays at the International Eel Laboratory, Miyazaki Prefecture, Japan. On the same day, 500 ml of surface water was filtered from the corner of the controlled pond (45 × 20 × 1 m, water volume = 850,000 l) containing 20 individuals of A. japonica with the total length ranging from 52 to 80 cm.

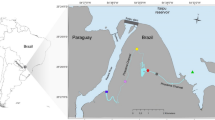

For natural rivers, 500 ml of surface water was filtered from the Ebitorigawa River (35.550°N, 139.752°E), the upper estuaries of the Ito-Miyagawa River (35.002°N, 139.082°E; 35.003°N, 139.080°E), Ito-Nakagawa River (35.005°N, 139.083°E) and Karasugawa River (35.008°N, 139.085°E) in Tokyo or Shizuoka, Japan on 10 September 2017 (Fig. 2). All of the rivers are known as suitable habitats for A. japonica. Each freshwater sample was carefully filtered without entering the river to avoid possible contamination. A filtration blank was created by filtering 500 ml of sterile distilled H2O in the same manner as eDNA samples after the end of the water sampling each day. Ten filter cartridges (two from tanks, one from the controlled pond, five from the rivers and two filtration blanks) were transported to the laboratory in a cooler with ice, and then kept at −20 °C for about 20 days until eDNA extractions.

Water sampling sites (yellow circles). The Karasugawa River (35.008°N, 139.085°E), Ito-Nakagawa River (35.005°N, 139.083°E), and Ito-Miyagawa River (35.002°N, 139.082°E; 35.003°N, 139.080°E) in Shizuoka and the Ebitorigawa River (35.550°N, 139.752°E) in Tokyo. The map overlay shows the sampling locations (yellow squares) within Shizuoka and Tokyo Prefectures within central Japan. Panels were made from imagery obtained from the Google Earth program.

Library preparation and MiSeq sequencing with eDNA samples

Strict clean-lab procedures were adopted when eDNA samples were analyzed to minimize contamination. Prior to eDNA library preparations, work-space and equipment were totally sterilized, filter pipet tips were used, and separation of pre- and post-PCR was carried out to safeguard against contamination. Extraction, the 1st PCR, and the 2nd PCR blanks were processed alongside the eDNA samples to monitor contamination.

eDNA was extracted from all cartridges using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacture’s protocol and the method developed by Miya et al.9,37. All eDNA extracts including blanks were used for multiplex PCR using fish universal primers MiFish (from Miya et al.9) plus MiEel primers for a correct assignment of Anguilla. When the 1st PCR was multiplexed, the final concentration of each primer was 0.3 µM, and sterile distilled H2O was added up to the total reaction volume of 12 µl. Eight PCR replications were made per one of each eDNA extract (except for all blanks) for the 1st PCR to avoid missing detection of target species that are actually present38. The eight PCR replications of each extract were pooled, and then the pooled product was purified in the elution volume of 12 µl using a MiniElute Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). The purified 1st PCR product was diluted to 0.1 ng µl−1 and used as a template for the 2nd PCR. Except for the multiplex reaction and multiple replications in the 1st PCR, all conditions and procedures for the 1st PCR, 2nd PCR and MiSeq sequencing were the same as used in the analysis of the mock communities.

Data processing and taxonomic assignment of MiSeq reads

All data preprocessing and analysis of MiSeq raw reads were done using USEARCH v10.0.24039 by performing the following steps. (1) both forward and reverse reads were merged by aligning them using the fastq_mergepairs command. During this process, low-quality tail reads with a cut-off threshold set at a Phred score of 20 (=10−2 error rate), and those paired reads with too many differences (>5 positions) in the aligned region (ca. 70 bp) were discarded; (2) primer sequences were removed from those merged reads using the fastx_truncate command; (3) those reads without the primer sequences underwent quality filtering using the fastq_filter command to remove low quality reads with an expected error rate of >1% and too short reads of <120 bp; (4) the preprocessed reads were dereplicated using the fastx_uniques command and all singletons, doubletons and tripletons were removed from the subsequent analysis following the recommendation by ref.39; (5) the dereplicated reads were denoised using the unoise3 command and, all putatively chimeric and erroneous sequences were separated from the subsequent operational taxonomic unit (OTU) assignment; and 6) finally all processed reads were assigned to OTU with a sequence identity of 98.5% (two nucleotide differences allowed) using the usearch_global command and the outputs were tabulated with read abundances. We processed the data of sequences reads as acceptable results when no reads had been detected from any blanks.

Ethical statement

All experiments in this study were conducted without direct captures of live fish and were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All experimental protocols were approved by Institutional guidelines for animal care of Nihon University.

Results

MiEel primers

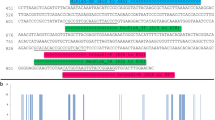

By visual examination of the aligned whole mitochondrial genomes from 19 species of Anguilla, two conserved regions that flank a variable region (167 bp) were located within the ATP6 gene. The new PCR primers for metabarcoding eDNA from the genus Anguilla were designed on the two conserved regions, and were named MiEel (Tables 1, 2). The MiEel-forward (MiEel-F) comprised 5′–CTTACAGCAAACCTGACAGCAG –3′, while the MiEel-reverse (MiEel-R) comprised 5′–TTGGTGTGCCATTATACGTTTTCTTG–3′ (universal primers, Table 1). The MiEel forward and reverse primers without adapter sequences consisted of 22 and 26 bases with Tm of 55.7 °C and 55.9 °C, and G/C content of 50% and 38% respectively. Of the 19 anguillid eels, 12 species had a single base pair mismatch in the MiEel forward primer (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S1a). The 12 mismatches were unconventional T-G base pairing in 10 species and A-C base pairing in two species (Table 2). On the other hand, the reverse primer had identical sequence match with all reference sequences from Anguilla (Table 2, Supplementary Fig. S1b).

Nucleotide variations in the MiEel forward primers (MiEel-F) among 19 species/subspecies of Anguilla and other anguilliforms (Stemonidium hypomelas, Nemichthys scolopaceus, Moringua edwardsi, Conger myriaster, Rhinomuraena quaesita, Gymnothorax kidako, Muraenesox bagio). Dots indicate that nucleotides are identical to those of MiEel-F on the top line.

MiEel primers without adapter sequences were able to amplify each variable region of all 19 species and subspecies of the genus Anguilla using tissue-extracted DNA. The variable region of all Anguilla showed uncorrected pairwise distances from 0.6 to 13.2% with an average of 9% and nucleotide differences from one to 22 with an average of 14.

The sequence similarity between the MiEel primers and 19 other closely related anguilliform species appeared to be high (Supplementary Fig. S1c,d). The uncorrected pairwise distances for the variable regions between Anguilla and the anguilliforms ranged from 13.2 to 33.2% with an average 22.7% (Supplementary Fig. S2, Table S1). Therefore, MiEel primers would amplify eDNA from other anguilliforms, while the variable regions included sufficient nucleotide differences to distinguish Anguilla and the other anguilliforms.

The smallest nucleotide difference of one base pair was found between the two subspecies of A. bengalensis. Other subspecies groups (A. australis and A. bicolor) showed small intersubspecific variations with three base pair differences in the targeted ATP6 region. The neighbor-joining tree showed that the nucleotide differences in the ATP6 sequences amplified by MiEel primers were higher than those in the 12S rRNA regions amplified by MiFish primers with an average of 6 (range: 0–14) for Anguilla (Fig. 1), indicating that the MiEel primers had a higher taxonomic resolution to the genus.

Species detection from mock communities

Except for two subspecies (A. australis schmidtii and A. bengalensis bengalensis), the metabarcoding of six mock communities detected 17 species and subspecies of Anguilla (Fig. 4). The taxonomic assignment of the 17 detected species and subspecies corresponded with the species whose tissue-extracted DNA were added to each mock community. This demonstrated that the MiEel metabarcoding enabled the reads to be distinguished at the species level with identity of more than or equal to 98.5%. The number of sequence reads were variable among the species (Fig. 4). As the number of species whose tissue-extracted DNA were mixed into the same mock community increased, the sequence reads of each species tended to decrease (Fig. 4). Anguilla bicolor pacifica and A. borneensis were not found from the mock communities #2 and #5, and their overall detections were a few reads (3–14 reads) compared with other species (Fig. 4). Seven sequence reads were detected from A. anguilla, but its extracted DNA was not added to the mock community #2 (Fig. 4). The 1st PCR and the 2nd PCR blanks were negative.

Species detection from eDNA samples

The MiEel eDNA metabarcoding detected the correct species living in the two aquarium tanks (Table 3). The eDNA from A. bicolor bicolor (224 reads) was detected from the tank that contained a single individual of that species. Anguilla australis australis (16,360 reads) was detected from the other tank containing A. australis sp. eel whose subspecies identification had been unclear.

The MiEel analysis of the six freshwater samples from the controlled pond and natural rivers all detected eDNA from A. japonica without visual observation of the eels (Table 3). The more than 8000 sequence reads of A. japonica from the controlled pond was the highest number of reads among all freshwater samples. Only a modest eight reads were obtained from Ebitorigawa River, and more than 290 reads were detected from the other three rivers (Table 3). All filtration, extraction, the 1st PCR and the 2nd PCR blanks yielded no reads of the genus Anguilla, providing no indication of contamination.

Discussion

Utility of eDNA metabarcoding with MiEel primers

The development of the MiEel primers enabled sequence reads of freshwater eels to be assigned at the species level. With the newly designed MiEel primers without adapter sequences, variable sequences (167 bp) within the ATP6 gene were confirmed using the tissue-derived DNA extracts from 19 Anguilla species/subspecies. The variable sequences could be used to distinguish each species of Anguilla. The similarity of sequences between the MiEel primers and the ATP6 sequences of some species of anguilliforms including Anguilla indicated that there is a possibility that the primers could amplify eDNA from other anguilliforms (Supplementary Fig. S1c,d). However, there would be no risk of incorrect taxonomic assignments through misidentification of sequence reads because the 167 bp of ATP6 sequences that would be amplified by the MiEel primers included sufficient nucleotide differences between Anguilla and other anguilliforms (Supplementary Fig. S2, Table S1). Therefore, the MiEel primer should work well for eDNA metabarcoding to Anguilla.

The MiEel metabarcoding with six mock communities containing 2–19 Anguilla species tissue DNA extracts demonstrated a simultaneous PCR amplification and taxonomic assignment at the species level, but failed to detect two subspecies A. australis schmidtii and A. bengalensis bengalensis (Fig. 4). In addition, eDNA of some freshwater eels were successfully detected from two aquarium tanks, the controlled pond, and four natural rivers (Table 3). Therefore, the eDNA metabarcoding with the MiEel primers provided information on the presence or absence of some Anguilla species without capturing them, which indicated it can be a useful approach to estimate their distribution in freshwater and marine habitats.

The MiEel metabarcoding would be particularly effective for documenting species distributions in aquatic environments where many Anguilla species might occur sympatrically. For example, eight species probably occur within and near the Indonesian archipelago that include A. bengalensis, A. bicolor, A. borneensis, A. celebesensis, A. interioris, A. marmorata, A. megastoma, and A. obscura40. There are also six anguillid species that live and spawn in the western South Pacific region41,42. Species identification of those Anguilla species still remains difficult because morphological traits of their larvae partially or completely overlap among some species and genetic identification is required43,44, and the same problem exists for some of their adults45. Genetic species identification of collected specimens of Anguilla has been conducted using a portion of 16S rRNA and cyt b genes43,44,46. Even if genetic identification is used, intensive efforts are still required to collect the eels or larvae to identify the distribution and possible spawning areas. In contrast, the MiEel metabarcoding allowed simultaneous detection of freshwater eels at the species level from water samples without much sampling effort and expertise in taxonomy (Fig. 4, Table 3). If the aim is to examine the presence/absence of several species of Anguilla that can be sympatrically distributed in aquatic environments like in the Indonesian archipelago, on islands of the western South Pacific and in offshore spawning areas, eDNA metabarcoding with the MiEel primers will provide fast and efficient insight into the distribution. The MiEel metabarcoding is expected to work as a powerful supplement to the conventional sampling methods for natural resource management and ecological studies of freshwater eels.

Taxonomic assignment to freshwater eels

Our study found, however, that the discrimination of the three subspecies pairs A. australis, A. bengalensis, A. bicolor may be ambiguous when using the eDNA metabarcoding with MiEel primers. The two subspecies of A. bengalensis had the smallest nucleotide differences of one base among all species/subspecies pairs, which is followed by the two subspecies pairs of A. australis and A. bicolor with three nucleotide differences (Fig. 1). Such small differences may pose serious limits for subspecies assignment because of erroneous sequence reads from an NGS platform. Although a denoising process was introduced in the present analysis, there were still erroneous sequences, which will introduce both false positives and negatives39. Fortunately, the three subspecies likely do not usually overlap in the geography of their freshwater habitats47.

The limitation for distinguishing anguillid subspecies suggested though, the taxonomic assignment of sequence reads to the freshwater eels can still be improved. Species identification using eDNA metabarcoding crucially depends on correct and reliable reference sequence database9,14,48,49, so the database must consist of DNA sequences from properly vouchered and correctly identified species. In this study, reference sequences were derived from 167 bp of ATP6 sequences from each species and subspecies of Anguilla that were morphologically and genetically identified (19 sequences; see Methods). The 167 bp sequences of 13 Anguilla species were identical with those registered previously in DDBJ by Minegishi et al.28,29, but there was one mismatch for A. reinhardtii, A. australis schmidtii and A. dieffenbachii, and were two mismatches for A. celebesensis and A. bicolor pacifica. These mismatches were unable to be determined as intraspecific variations because of few reliable ATP6 sequences of Anguilla being available in public databases. The improvement of the sequence assignment requires an increase of ATP6 sequence data verified by a concerted effort between taxonomists and molecular systematists.

False positive and false negative

A false positive (species is detected where it is not present) and false negative (species is not detected where it is present) have been frequently discussed as an important issue in eDNA studies9,14,49. For example, seven sequence reads of A. anguilla were detected from the mock community #2 although the tissue-derived DNA of that species was not mixed into it (Fig. 4), indicating a false positive occurred. Laboratory contamination is especially serious because of frequent use of PCR generating billions of DNA copies, which can easily spread throughout a laboratory49. Moreover, handling PCR products and evaporation of these may result in DNA invasion into the surrounding air and subsequent formation of DNA aerosols, which cause a risk of contamination50,51. The tissue DNA extraction of freshwater eels and the library preparation for the MiEel metabarcoding using the mock communities was conducted in the same work space. Some aerosolized DNA that produce false positives might have been present in the work space when analyzing the mock communities. Since the 1st PCR and the 2nd PCR blanks turned out negative, the source of low sequence reads from A. anguilla most likely was aerosolized DNA being in the work space when the six mock communities were created.

In contrast, A. australis schmidtii, A. bengalensis bengalensis, A. bicolor pacifica and A. borneensis were usually not detected from the mock communities #2, #4 or #5 containing ≥8 species and subspecies, which showed the occurrence of false negatives despite their tissue DNA being added to the mock communities. PCR bias derived from primer-template mismatches is a possible factor causing imperfect detections9. Importantly, MiEel primers were able to amplify each variable region for all freshwater eels using tissue extracted DNA when analyzed separately. This implied that MiEel metabarcoding should be able to simultaneously detect multiple anguillid eels from a single water sample. However, amplification efficiencies for all DNA templates in the mock communities containing many species (a large number of competing templates) are not always equal because 12 anguillid eels including A. bengalensis bengalensis, A. bicolor pacifica and A. borneensis have one mismatch with the MiEel forward primer (Fig. 3). Because there are problems with the stochasticity of individual PCR reactions and PCR bias derived from primer-template mismatches, the eDNA metabarcoding needs some methodological improvements to mitigate PCR dropouts in cases with many templates in a single sample. Increasing the number of PCR replications and pooling them were recommended to reduce the risk of false negatives in eDNA metabarcoding studies9,38,52. However, it is unlikely that a single water sample will include eight or more anguillid eels in natural environments.

To avoid the false positive and false negative detections, which were in fact observed in the analysis of the mock communities, the eDNA samples were analyzed with some optimizations to strictly monitor contamination and to increase a detection probability. All blanks (filtration, extraction, the 1st PCR and the 2nd PCR) were processed in parallel to the analysis of eDNA samples, and then produced negative results. Thus, eDNA samples may not have been contaminated with any DNA from freshwater eels during filtration, extraction, the 1st PCR and the 2nd PCR. Unlike the unexpected detection of A. anguilla from the mock community #2 (Fig. 4), the MiEel metabarcoding using the eDNA samples yielded no reads of irrelevant Anguilla species (Table 3). This implied that the strict clean-lab procedures (e.g. separation of the working place) worked well for safeguarding contamination. Moreover, eight PCR replicates per one of each eDNA extract were subjected to the 1st PCR. To reduce the rate of false negatives, the eight PCR replicates should be performed if detection probability is low38. The on-site filtration method at water sampling sites using the filter cartridges and the syringe is also ideal to minimize false negatives because this method will provide more intact eDNA37. Without those optimal strategies to minimize false positive and false negative, it was impossible to recover low abundant sequences such as the reads of Ebitorigawa River, in which A. japonica is expected to be present, from the field eDNA samples (Table 3). The sequence reads of A. japonica detected from the Ebitorigawa River were only a modest eight reads, but verified that the eDNA metabarcoding using the MiEel reflected the species distribution of Anguilla there because no reads were detected from any blanks. This result emphasized the importance of strict and optimal protocols to detect target species with confidence, especially when the application of the eDNA metabarcoding in the field.

Data Availability

Raw reads of the mock communities and eDNA samples from the MiSeq sequencing are available from the DDBJ Sequence Reads Archive (Accession Number DRA005271 and DRA006504).

References

Taberlet, P., Coissac, E., Hajibabaei, M. & Rieseberg, L. H. Environmental DNA. Mol Ecol. 21, 1789–1793 (2012).

Kelly, R. P. et al. Harnessing DNA to improve environmental management. Science. 344, 1455–1456 (2014).

Ficetola, G. F., Miaud, C., Pompanon, F. & Taberlet, P. Species detection using environmental DNA from water samples. Biol Lett. 4, 423–425 (2008).

Jerde, C. L., Mahon, A. R., Chadderton, W. L. & Lodge, D. M. “Sight-unseen” detection of rare aquatic species using environmental DNA. Conserv Lett. 4, 150–157 (2011).

Wilcox, T. M. et al. Robust detection of rare species using environmental DNA: the importance of primer specificity. PLoS One. 8, e59520 (2013).

Fukumoto, S., Ushimaru, A. & Minamoto, T. A basin-scale application of environmental DNA assessment for rare endemic species and closely related exotic species in rivers: a case study of giant salamanders in Japan. J Appl Ecol. 52, 358–365 (2015).

Bergman, P. S., Schumer, G., Blankenship, S. & Campbell, E. Detection of adult Green Sturgeon using environmental DNA analysis. PLoS One. 11, e0153500 (2016).

Thomsen, P. F. et al. Detection of a diverse marine fish fauna using environmental DNA from seawater samples. PLoS One. 7, e41732 (2012).

Miya, M. et al. MiFish, a set of universal PCR primers for metabarcoding environmental DNA from fishes: detection of more than 230 subtropical marine species. R Soc Open Sci. 2, 150088 (2015).

Valentini, A. et al. Next-generation monitoring of aquatic biodiversity using environmental DNA metabarcoding. Mol Ecol. 25, 929–942 (2016).

Shaw, J. L. A. et al. Comparison of environmental DNA metabarcoding and conventional fish survey methods in a river system. Biol Conserv. 197, 131–138 (2016).

Riaz, T. et al. ecoPrimers: inference of new DNA barcode markers from whole genome sequence analysis. Nucl Acid Res. 39, e145 (2011).

Yamamoto, S. et al. Environmental DNA metabarcoding reveals local fish communities in a species-rich coastal sea. Sci Rep. 7, 40368 (2017).

Klymus, K. E., Marshall, N. T. & Stepien, C. A. Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding assays to detect invasive invertebrate species in the Great Lakes. PLoS One. 12, e0177643 (2017).

Jacoby, D. M. P. et al. Synergistic patterns of threat and the challenges facing global anguillid eel conservation. Glob Ecol Conserv. 4, 321–333 (2015).

IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 3, 2017.5, https://www.iucnredlist.org (2017).

Tsukamoto, K. Oceanic migration and spawning of anguillid eels. J Fish Biol. 74, 1833−1852 (2009).

Chow, S. et al. Discovery of mature freshwater eels in the open ocean. Fish Sci. 75, 257–259 (2009).

Tsukamoto, K. et al. Oceanic spawning ecology of freshwater eels in the western north Pacific. Nat Commu. 2, 179 (2011).

Baras, E., Jeandrain, D., Serouge, B. & Philippart, J. C. Seasonal variations in time and space utilization by radio-tagged yellow eels Anguilla anguilla (L.) in a small stream. Hydrobiol. 372, 187–198 (1998).

Aoyama, J. et al. A preliminary study of the movements of yellow and silver eels, Anguilla japonica, in the estuary of the Fukui River, Japan, as revealed by acoustic tracking. Hydrobiol. 470, 31–36 (2002).

Parker, S. J. Homing ability and home range of yellow-phase American eels in a tidally dominated estuary. J Mar Biol Assoc UK. 75, 127–140 (1995).

Jellyman, D. J. & Sykes, J. R. E. Diel and seasonal movements of radio-tagged freshwater eels, Anguilla spp., in two New Zealand streams. Env Biol Fish. 66, 143–154 (2003).

Thibault, I., Dodson, J. J. & Caron, F. Yellow-stage American eel movements determined by microtagging and acoustic telemetry in the St Jean River watershed, Gaspé, Quebec, Canada. J Fish Biol. 71, 1095–1112 (2007).

Jensen, M. R., Knudsen, S. W., Munk, P., Thomsen, P. F. & Møller, P. R. Tracing European eel in the diet of mesopelagic fishes from the Sargasso Sea using DNA from fish stomachs. Mar Biol. 165, 130 (2018).

Knudsen, S. W. et al. Species-specific detection and quantification of environmental DNA from marine fishes in the Baltic Sea. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 510, 31–45 (2019).

Takeuchi, A. et al. First use of oceanic environmental DNA to study the spawning ecology of the Japanese eel Anguilla japonica. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 609, 187–196 (2019).

Minegishi, Y. et al. Molecular phylogeny and evolution of the freshwater eels genus Anguilla based on the whole mitochondrial genome sequences. Mol Phylogen Evol. 34, 134–146 (2005).

Minegishi, Y., Aoyama, J., Inoue, J. G., Azanza, R. V. & Tsukamoto, K. Inter- specific and subspecific genetic divergences of freshwater eels, genus Anguilla including a recently described species, A. luzonensis, based on whole mitochondrial genome sequences. Coast Mar Sci. 33, 64–77 (2009).

Katoh, K. & Toh, H. Recent developments in the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Brief Bioinformatics. 9, 286–298 (2008).

Maddison, W. P. and Maddison, D. R. Moesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. version 2.75 See, http://www.mesquiteproject.org (2010).

Kibbe, W. A. Oligocalc: an online oligonucleotide properties calculator. Nucl Acid Res. 35, W43–W46 (2007).

Crooks, G. E., Hon, G., Chandonia, J. M. & Brenner, S. E. WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190 (2004).

Inoue, J. G. et al. Deep-ocean origin of the freshwater eels. Biol Lett. 6, 363–366 (2010).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A. & Kumar, S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 30, 2725–2729 (2013).

Watanabe, S. Taxonomic study of the freshwater eels, the genus Anguilla, Schrank1798. PhD thesis (University of Tokyo, 2001) (in Japanese).

Miya, M et al. Use of a filter cartridge for filtration of water samples and extraction of environmental DNA. J Vis Exp. e54741 (2016).

Ficetola, G. F. et al. Replication levels, false presences and the estimation of the presence/absence from eDNA metabarcoding data. Mol Ecol Resour. 15, 543–556 (2015).

Edgar, R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinform. 26, 2460–2461 (2010).

Sugeha, H. Y., Suharti, S. R., Wouthuyzen, S. & Sumadhiharga, K. Biodiversity, distribution and abundance of the tropical anguillid eels in the Indonesian waters. Mar Res Indones. 33, 129–138 (2008).

Jellyman, D. J. The distribution and biology of the South Pacific species of Anguilla. In Eel Biology (eds Aida, K., Tsukamoto, K. & Yamauchi, K.) 275–292 (Tokyo, Springer-Verlag, 2003).

Kuroki, M., Miller, M. J. & Tsukamoto, K. Diversity of early life-history traits in freshwater eels and the evolution of their oceanic migrations. Can J. Zool. 92, 749–770 (2014).

Aoyama, J. et al. Distribution and dispersal of anguillid leptocephali in the western Pacific Ocean revealed by molecular analysis. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 188, 193–200 (1999).

Kuroki, M. et al. Distribution and early life-history characteristics of anguillid leptocephali in the western South Pacific. Mar Freshw Res. 59, 1035–1047 (2009).

Watanabe, S., Aoyama, J. & Tsukamoto, K. Reexamination of Ege’s (1939) use of taxonomic characters of the genus Anguilla. Bull Mar Sci. 74, 337−351 (2004).

Watanabe, S., Aoyama, J. & Tsukamoto, K. The use of morphological and molecular genetic variations to evaluate subspecies issues in the genus Anguilla. Coast Mar Sci. 32, 19–29 (2008).

Watanabe, S. Taxonomy of the freshwater eels, genus Anguilla Schrank, 1798. In Eel Biology (eds Aida, K., Tsukamoto, K. & Yamauchi, K.) 3–18 (Tokyo, Springer-Verlag, 2003).

Zhang, A. B. et al. A fuzzy-set-theory-based approach to analyse species membership in DNA barcoding. Mol Ecol. 21, 1848–1863 (2012).

Thomsen, P. F. & Willerslev, E. Environmental DNA – an emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity. Biol Conserv. 183, 4–18 (2015).

Zhang, C., Xu, J., Ma, M. & Zheng, W. PCR microfluidic devices for DNA amplification. Biotechnol Adv. 24, 243–284 (2006).

Yang, W., Zhu, R., Zhang, C. & Li, Z. Application and performance test of a small aerosol sensor for the measurement of aerosolized DNA stands. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 17, 2358–2366 (2017).

Schmidt, P. A. et al. Illumina metabarcoding of a soil fungal community. Soil Biol Biochem. 65, 128–132 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jun Aoyama for providing the tissue samples. This paper greatly benefited from critical comments and suggestions by Satoshi Yamamoto and Michael. J. Miller, and Ritsuno Yama helped with various aspects of the project. This research was supported by CREST (JPMJCR13A2) from JST (M.M.), Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (4–1602) of the Ministry of the Environment, Japan (M.M.), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (JP26252030, JP17K19300, JP19H00946) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (K.T.), Sasakawa Scientific Research Grant (28–531) from the Japan Science Society (A.T.) and JSPS Research Fellowships for Young Scientists (JP18J10466) (A.T.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M., K.T., S.W. and A.T. conceived and designed the experiment. M.M., T.S. and A.T. performed the experiment. M.M., R.G. and A.T. analyzed the data. M.M., K.T., S.W., R.G., T.S. and A.T. provided reagents, materials and analysis tools. S.W. previously conducted the identification of Anguilla used for the tissue samples in this study by both morphological observations and molecular methods. A.T. wrote the early draft. M.M., K.T., S.W. and R.G. helped write manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript, approved the final version of the paper and take responsibility for it.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Takeuchi, A., Sado, T., Gotoh, R.O. et al. New PCR primers for metabarcoding environmental DNA from freshwater eels, genus Anguilla. Sci Rep 9, 7977 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44402-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44402-0

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.