Abstract

Hexagonal close-packed iron hydride, hcp FeHx, is absent from the conventional phase diagram of the Fe–H system, although hcp metallic Fe exists stably over extensive temperature (T) and pressure (P) conditions, including those corresponding to the Earth’s inner core. In situ X-ray and neutron diffraction measurements at temperatures ranging from 298 to 1073 K and H pressures ranging from 4 to 7 GPa revealed that the hcp hydride was formed for FeHx compositions when x < 0.6. Hydrogen atoms occupied the octahedral interstitial sites of the host metal lattice both partially and randomly. The hcp hydride exhibited a H-induced volume expansion of 2.48(5) Å3/H-atom, which was larger than that of the face-centered cubic (fcc) hydride. The hcp hydride showed an increase in x with T, whereas the fcc hydride showed a corresponding decrease. The present study provides guidance for further investigations of the Fe–H system over an extensive x–T–P region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transition metals react with hydrogen to form hydrides, MHx, at hydrogen pressures of several gigapascals (GPa; hereafter, the hydrogen pressure is referred to simply as “pressure”)1. Hydrogen molecules dissociate to hydrogen (H) atoms on the metal surface, where the H atoms dissolve into the bulk to partially or fully occupy the interstitial sites of the metal lattice. The interstitial H atoms expand the volume of the metal lattice by 10–20% for a MHx composition of x = 11. The H composition x varies as a function of the temperature (T) and pressure (P). Accordingly, the volume of hydride (V) varies via a hydrogen-induced volume expansion. In addition to V, x is an essential variable for describing the bulk state of a hydride. Hydrogen compositions for recovered specimens have been measured by neutron diffraction or hot extraction of H2 gas at ambient pressure2. In situ neutron diffraction was recently used to investigate the structure of iron deuteride under high T–P conditions, and the D composition was successfully determined3.

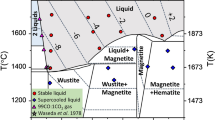

Iron hydride (FeHx) has been intensively studied for half a century as a prototype of transition-metal hydrides2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 and an endmember of the constituents of the Earth’s core5,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Figure 1, plotted from previously reported data2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10, shows a schematic of the x–T–P diagram of the Fe–H system at temperatures from 300 to 1400 K and pressures ranging from 0 to 10 GPa 2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Three phases exist: a low-pressure α phase with a body-centered cubic (bcc) structure, wherein Fe atoms occupy the vertexes of the bcc lattice; a high-temperature γ phase with a face-centered cubic (fcc) structure and a high-pressure εʹ phase with a double hexagonal close-packed (dhcp) structure. The bcc and fcc phases are a solid solution of hydrogen for x <1.0, whereas the dhcp phase is a monohydride for x = 1 over almost the entire stable T–P region. The triple point is located at approximately 520 K and 5 GPa2,4,9,10, where the bcc, dhcp, and fcc phases have approximate H compositions of 0.1, 1.0, and 0.5, respectively5,7,8,9,10. The phase stability for iron hydride in equilibrium with fluid hydrogen has been investigated, where the composition x was uniquely fixed to the highest value at a given T–P condition for each hydride phase. A different hydride should form for x values below the equilibrium x surface. The hcp hydride is absent in the conventional phase diagram although the hcp phase of metallic iron is stable at extensive T–P conditions up to those corresponding to the Earth’s inner core25.

We performed structural investigations on the Fe–H system to explore the formation of the hcp hydride at x–T–P conditions below the equilibrium x surface. In situ X-ray diffraction measurements revealed that the hcp hydride appeared at ~800 K while the fcc hydride was cooled from ~1000 K at ~7 GPa under conditions where there was no coexisting fluid H2 (red arrow in the inset of Fig. 1). The hcp hydride subsequently decomposed into dhcp FeH and bcc Fe at ~430 K upon further cooling. The crystal structure including the site occupancy of deuterium (D) atoms was investigated via in situ neutron diffraction measurements of the hcp deuteride, which was prepared by cooling the fcc deuteride (blue arrow in the inset). In this communication, we present x–T–P conditions for the formation of the hcp hydride and the variation of x with the fcc–hcp–dhcp structural transitions. Hydrogen-induced volume expansion and the x–T relation, which are essential properties for characterizing metal hydrides, are derived from the structural data and compared with those of the fcc hydride.

Results

X-ray diffraction measurements

The X-ray diffraction profiles were collected while cooling fcc FeHx with x ≈ 0.6 from 1073 K to 298 K at an initial pressure of ~7 GPa. In this experiment, the amount of aluminum trihydride (AlH3) pellets that was used as an internal H source was reduced to a H/Fe molar ratio of ~0.6 to prevent transformation from fcc FeHx to the monohydride dhcp FeH with additional H absorption. The temperature was continuously decreased at 10 K/min, and the pressure was reduced from 7.1 to 5.0 GPa because of the thermal contraction of the reaction cell. Time-resolved X-ray diffraction profiles were collected with an exposure time of 20 s/profile using the energy dispersion method26.

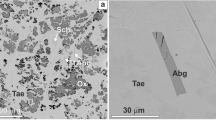

Figure 2(a) Shows the evolution of the diffraction profile with decreasing temperature. The observed profiles are divided into approximately three regions for ease of explanation: fcc-dominant (Fig. 2(b)), hcp-dominant (Fig. 2(c)), and dhcp-dominant regions (Fig. 2(d)).

X-ray diffraction profiles collected for iron hydride upon cooling, showing (a) overall evolution and (b) fcc-dominant, (c) hcp-dominant, and (d) dhcp-dominant regions; reflection indices are assigned to the major peaks of each structure, where the shifts of the fcc 111 and hcp 101 peaks are indicated by broken lines to guide the eye.

When the temperature decreased to ~800 K, only one peak appeared (~60 keV, d ≈ 2.0 Å) in addition to those of the fcc hydride, as shown in Fig. 2(b). The peak intensity increased with further decrease in the temperature to ~750 K, whereas the peak intensity of the fcc peaks remained unchanged. Other new peaks appeared at ~650 K. These peaks were assigned as hcp lattice reflections, indicating a transformation from the fcc to the hcp structure. The most intense 101 peak (denoted by the arrow in Fig. 2(c)), which appeared on the low-energy side of the preceding 101 peak, was shifted to a higher energy with decreasing temperature, thereby merging with the energy level of the 101 peak in Fig. 2(b). We assigned the preceding peak at temperatures of 800–750 K as a hcp 101 peak from “precipitated hcp hydride” and the peaks appearing at ~650 K were assigned to “transformed hcp hydride.”

The fcc–hcp structural transformation proceeded until ~480 K (Fig. 2(c)). The fcc 111 peak was shifted to a lower energy because of volume expansion with H absorption; by contrast, the hcp 101 peak was shifted to a higher energy because of volume contraction with H desorption. The hcp hydride eventually decomposed into dhcp FeHx (x ≈ 1.0) and bcc Fe (Fig. 2(d)) at ~430 K. The diffraction profiles showed peaks from the fcc and hcp hydrides at temperatures below ~650 and ~430 K, respectively. A small amount of the fcc and hcp hydrides remained in a metastable state, probably because of slow transformation kinetics at lower temperatures. The diffraction peaks continued to shift to lower or higher energies in the metastable temperature ranges, and the corresponding peak positions were used to calculate the lattice constants or atomic volumes of Fe, as described in the following paragraphs.

Neutron diffraction measurements

We performed neutron diffraction measurements with the same reaction cell as that used in the X-ray diffraction experiments, except that the AlH3 pellet was replaced with an AlD3 pellet3,27,28. An excess amount of AlD3 with a Fe/D molar ratio of ~1.5 was charged into the cell to completely deuterize a bulk Fe specimen, 3.0 mm in diameter and 2.5 mm in thickness, within a short time. However, deuterization of the Fe disc took 90 min even at temperatures as high as 1073 K. By contrast, only a few minutes were required for the hydrogenation of Fe flakes, which were mixed with the BN powder that was used in the X-ray diffraction experiments. This result was expected because the surface areas for the Fe disc and flakes differed by orders of magnitude. After the formation of the fcc deuteride at 1073 K and 6.0 GPa was confirmed by neutron diffraction, the temperature was rapidly decreased to 673 K to prevent the fcc deuteride from achieving an equilibrium D composition; the hcp deuteride was thus prepared. The temperature was further decreased to 573 K and finally to 300 K. A neutron diffraction profile was collected at each temperature with a few hours of integration time. The pressure decreased from 6.0 to 4.2 GPa upon cooling to 300 K.

Figure 3 shows the neutron diffraction profiles that were recorded at 1073 K and 6.0 GPa (a), 673 K and 5.1 GPa (b), and 300 K and 4.2 GPa (c). The corresponding simulated and experimental profiles, as fitted by Rietveld refinement29, are shown. It should be noted that the Fe and D compositions of the fcc deuteride are denoted by xʹ in the panels (a) and (b). The site occupancy of the Fe atoms in the fcc lattice deviated slightly from unity to xʹ < 1.0 because of the formation of vacancies at the Fe sites9,10,30. The Rietveld refinement only provides the ratio of the site occupancies between Fe and D atoms; hence, the Fe composition is described by xʹ.

Experimental and simulated neutron diffraction profiles of iron deuteride at (a)1073 K and 6.0 GPa, (b) 673 K and 5.1 GPa, and (c) 300 K and 4.2 GPa: blue lines indicate differences between the experimental (red dots) and simulated (blue curves) profiles; reflection indices are assigned to the major peaks of the dominant structures (a) fcc, (b) hcp, and (c) dhcp; tick marks indicate the positions of allowed Bragg peaks for each structure.

The diffraction peaks at 673 K showed that the hcp structure was the dominant component. Rietveld refinement using a hcp model structure with D atoms randomly occupying the interstitial sites yielded site occupations of 0.48(1) (hereafter, the numbers in parentheses denote the experimental error) and 0.0 for the octahedral and tetrahedral sites, respectively, and a deuterium composition of x = 0.48(1). A very similar diffraction profile was observed for the hcp deuteride at 573 K and 4.8 GPa, yielding x = 0.48(1). In the 300-K profile, the dominant diffraction peaks originated from dhcp FeD and bcc Fe; the hcp deuteride decomposed, as observed in the X-ray diffraction experiments. For dhcp FeD, we used a stacking fault model that was presented in the early neutron diffraction study8. Because bcc Fe and dhcp Fe(H/D) are ferromagnetic31,32, each diffraction peak contains a magnetic scattering component in addition to a nuclear one. The magnetic moment was optimized to 2.1 (1.1) in Bohr magnetons (μB) for bcc Fe. No magnetic contribution considered for dhcp FeD because the peak intensity was too low for the magnetic structure to be refined. The structural parameters that were optimized by Rietveld refinement are summarized in Table 1.

V–T relation

The atomic volume of Fe, vFe, which is calculated by dividing the unit cell volume of iron hydride by the number of Fe atoms contained in the cell, was obtained for each hydride from its X-ray and neutron diffraction data. The atomic volume was plotted as a function of temperature in the 298–1073 K range in Fig. 4. The atomic volumes of the fcc and hcp Fe metals, which were calculated using their equations of state33,34, are also plotted as references. For the precipitated hcp hydride, only the 101 peak was observed at temperatures in the 730–800 K range (Fig. 2(b)). The atomic volume for the precipitated hcp hydride was estimated from the measured d values of the 101 peak and the axial ratio of c/a = 1.600 that was obtained for the transformed hcp hydride. The atomic volumes were also calculated for the fcc and hcp hydrides that remained as metastable states below the transformation and decomposition temperatures, respectively.

(a) The vFe–T relations of fcc (blue solid diamonds), dhcp (purple open squares), and hcp (green solid triangles) hydrides and bcc Fe (brown open circles) obtained by X-ray diffraction, where the estimated atomic volumes for the precipitated hcp hydride are represented by green open triangles; (b) estimated atomic volumes determined by neutron diffraction, where the symbols have the same meaning as in the left panel; in both (a,b) panels, the calculated vFe–T relations for hcp Fe and fcc Fe are represented by green and blue lines, respectively.

The vFe–T relations in Fig. 4a were used to derive the deuterium-induced volume vD = ΔvFe/x1. Here, the excess amount of vD. that arises from the volume expansion of the metal lattice owing to the dissolution of H/D atoms can be calculated using ΔvFe = vFe (hydride) − vFe (reference metal). The value of vD for the hcp deuteride at 673 K and 5.1 GPa was found to be 2.51 (5) Å3/D atom using ΔvFe = 1.191 Å3, which was calculated from the vFe (hcp FeDx) and the calculated vFe (hcp Fe, which is plotted in Fig. 4b), and x = 0.48(1). Using alternative data for ΔvFe = 1.166 Å3 and x = 0.48(1) at 573 K and 4.8 GPa, we obtained vD = 2.45(4) Å3/D atom. We took an averaged value of 2.48(5) Å3/D atom for the vD of hcp deuteride. For dhcp FeD, a 2.42 (4) Å3/D atom was obtained using the structural data that are listed in Table 1, where the hcp Fe volume was used as the reference volume. The volume of ferromagnetic dhcp deuteride contains an unknown contribution from magnetic volume expansion; hence, the calculated value is an upper limit on vD. The volume data for fcc FeDx that were obtained by the neutron diffraction should be regarded with caution because the lattice volume for this deuteride is substantially reduced owing to vacancy formation in the metal lattice9,10,30. Hence, we used the vD value of 2.21(4) Å3/D atom, as has been previously reported for vacancy-free fcc FeDx3. The vD of the hcp hydride is the largest volume among those for iron hydrides.

x–T relation

The expanded volume, ΔvFe, for the fcc and hcp hydrides that was measured over a temperature range of 298–1073 K by X-ray diffraction was converted to H compositions using a proportionality relation, x = ΔvFe/vH, in which vH = vD is assumed. Figure 5 shows the x–T relations of the fcc and hcp hydrides that were calculated using vH = 2.21 and 2.48 Å3/H atom, respectively. The x value of the fcc hydride decreased slightly from 0.68 at 1073 K to 0.66 at 600 K, before increasing towards a saturated value of 1.0; the fcc monohydride and the dhcp monohydride formed at temperatures below ~430 K. The value of x ≈ 0.5 was obtained for the precipitated hcp hydride in the 700 to 800 K range, whereas the transformed hcp hydride showed a monotonic decrease in x with decreasing temperature below 650 K. Despite the very similar values of x ≈ 0.6 for the hcp and fcc hydrides at ~600 K, opposing trends were observed for the variation in the H compositions with the temperature below 600 K.

The x–T relations are shown for fcc (blue solid diamonds), hcp (green solid triangles), and dhcp (purple open squares) hydrides. The estimated compositions for the precipitated hcp hydride are represented by green open triangles. Vertical broken lines show the approximate precipitation, transformation, and decomposition temperatures. The inset shows the cooling T–P path.

Discussion

Iron hydride/deuteride with an hcp metal lattice was formed by the transformation from the fcc hydride/deuteride. In the early studies6,8, the hcp hydride/deuteride formed as an intermediate metastable state during the hydrogenation/deuterization of bcc Fe to dhcp Fe(H/D). The “transformed” hcp deuteride has the same crystal structure as that of the “intermediate” hcp deuteride as shown by the structural parameters presented in Table I and Table 3 of ref.8. The D atoms occupy the octahedral interstitial sites of the host metal lattice both partially and randomly; The present study provided a D composition of 0.48 for hcp deuteride at 673 K and 5.1 GPa, and at 573 K and 4.8 GPa. This value was slightly higher than 0.42 reported for hcp deuteride prepared at 623 K and 9.2 GPa8. The tetrahedral site occupation, reported for fcc FeDx3, or the formation of layered octahedral superstructures, reported for hcp TcHx and MnDx at x = ~1/235 was not observed.

The hcp iron hydride, in both its stable and metastable states, formed for x < 0.6 at pressures from 4 to 6 GPa (Table 1 and Fig. 5). This hcp hydride lies under the equilibrium x-surface in the phase diagram that is shown in Fig. 1. Controlling of the H composition plays a key role in the formation of hcp hydride. In the neutron diffraction measurements, the bulk fcc deuteride transformed to the hcp deuteride through the nonequilibrium state formed due to the relatively low diffusion rate of D atoms at the measured temperatures. In the X-ray diffraction measurements, the powder fcc hydride transformed to the hcp hydride under the condition of insufficient hydrogen supply. Both of the transformations occurred near the stable T–P region of dhcp phase; the hcp hydride, instead of the dhcp monohydride, was preferentially precipitated. These results suggest the formation of hcp hydride over a wide T–P region under controlled H composition. The most recent theoretical calculations have shown that the hcp hydride becomes more stable than the dhcp hydride when x <~0.5 at extensively high T–P conditions36. Further phase studies of the Fe–H system in extended x–T–P conditions are required to clarify the structural stability of the hcp hydride in terms of the H composition.

The crystal structures of iron hydride that appeared sequentially in the cooling experiments are drawn in Fig. 6. The fcc, hcp, and dhcp structures can transform into each other by sliding metal planes and tuning the H composition. At the fcc–hcp transformation temperature of ~650 K, the H composition of both hydrides is x = 0.6; hence, the fcc structure can transform to the hcp structure by simply altering the stacking sequence of the metal planes from ABCABC∙∙∙ to ABAB∙∙∙ along the body diagonal axis of the cubic lattice. For decomposition at ~430 K, the dhcp structure can form by altering the sequence from ABAB∙∙∙ to ABABACAC∙∙∙ along the c axis of the hcp lattice and filling all of the octahedral sites with H atoms.

Although each of the metal lattices has one octahedral site per Fe atom available for H-atom accommodation, the spatial arrangements of these lattices are quite different. The octahedra consisting of Fe atoms at the corners are connected by corner sharing in the fcc lattice but by face-sharing in the hcp lattice (Fig. 6). The dhcp lattice consists of a mixture of two configurations, as seen in its sequence ABABACAC∙∙∙. The face-sharing configuration substantially shortens the first-neighbor distance between the H atoms. For the coexisting state at 673 K and 5.06 GPa, the fcc lattice constant of a = 3.6901(3) Å and the hcp lattice constants of a = 2.60047(10) Å and c = 4.2280(4) Å were obtained (Table 1). These values provide first-neighbor distances of 2.609 Å and 2.114 Å for the fcc and hcp structures, respectively. The latter distance of 2.114 Å is very close to the critical distance of 2.1 Å, below which dissolved H atoms in metals cannot approach each other owing to interatomic repulsion forces37. Dissolved H atoms can preferentially occupy second-neighbor octahedral sites to avoid violating the 2.1-Å rule in the half-filled hcp lattice but not in the hcp monohydride. The 2.1-Å rule is a possible factor in the stabilization of the hcp structure for x < 0.6.

The hcp and fcc solid solutions exhibited opposing variations in x with the temperature. The two-step variation of the fcc hydride was interpreted in terms of a miscibility gap; solid solutions with high and low H compositions can coexist below a critical T–P point, at which the H solubility gap vanishes. For the fcc hydride, the miscibility gap was confirmed experimentally10,13 and the critical pressure was located at 4.0–4.5 GPa at a critical composition of x ≈ 0.413. The measured pressure range of 5.0–7.1 GPa was higher than the critical pressure; hence, the H composition of the fcc hydride increased along the high-composition boundary of the miscibility gap with decreasing temperature below ~600 K, as shown in Fig. 5. For the hcp hydride, a miscibility gap has been theoretically predicted38, but has not been experimentally confirmed. The observed monotonic decrease in the x–T curve for the hcp hydride that is shown in Fig. 5 implies that the critical pressure was above ~6 GPa. Consequently, the H composition decreased with decreasing temperature along the low-composition boundary of the miscibility gap.

Methods

X-ray diffraction

The starting material was reagent-grade pure iron flakes (purity: 99.9%) with a lateral particle size <100 μm and a thickness <20 μm. The flakes were mixed with BN powder (purity: 99% and grain size: >10 μm) at a volume ratio of 2:3 and compacted into a disc that was 0.5 mm in diameter and 0.2 mm in height. The sample disc was loaded along with a compacted AlH3 disc, which served as an internal H source, into a sleeve made of pyrolytic BN. This sleeve was placed into a NaCl capsule that was surrounded by a cylindrical graphite heater. The cell assembly was performed in the air. High pressures and temperatures were generated using a cubic-type multi-anvil press. The internal H source decomposed into fluid H2 and Al metal upon heating above 800 K. The fluid H2 reacted with the Fe specimen to form FeHx in the NaCl capsule. The temperature was monitored using Pt/Pt–13%Rh thermocouples with an uncertainty of less than 20 K. In situ X-ray diffraction measurements were conducted using synchrotron radiation at the BL14B1 beamline of SPring-8. Details of the high-pressure generation, the hydrogenation cell, and the in situ synchrotron-radiation X-ray diffraction technique are described elsewhere26.

Neutron diffraction

The cell assembly for the high-pressure neutron diffraction measurements was essentially the same as that used for X-ray diffraction. A compacted Fe disc, 3 mm in diameter and 2.5 mm in height, was prepared by pressing Fe flakes in a piston-cylinder-type mold. The Fe specimen was placed at the center of a NaCl capsule (5.5 mm in diameter and 8 mm in height) and AlD3 (isotopic purity: 96 atom% D) pellets, which served as an internal D source, was placed above and below the Fe specimen. The NaCl capsule was inserted into a cylindrical graphite heater and embedded in a pressure-transmitting medium made of MgO (17-mm edge cube). The cell assembly was performed in the air. In situ neutron diffraction measurements were conducted using the pulsed neutron source at the BL 11 (PLANET) beamline of J-PARC27. The collected diffraction profiles were refined using Z-Rietveld software (version 0.9.42.2)29. In the refinement, H atoms that were included as an impurity at four atom% were assumed to randomly occupy the D atom sites. For simplicity, the site occupancies of the H atoms and the H composition are notated as gD and x, respectively. The cell assembly and the high-pressure apparatus that was used for the neutron diffraction experiments are described in detail elsewhere3.

Data Availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and Methods. The crystallographic data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Fukai, Y. The Metal–Hydrogen System 2nd edn (Springer-Verlag 2005).

Antonov, V. E. et al. High-pressure hydrides of iron and its alloys. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 14, 6427–6445 (2002).

Machida, A. et al. Site occupancy of interstitial deuterium atoms in face-centred cubic iron. Nat. Commun. 5, 5063 (2014).

Antonov, V. E., Belash, I. T. & Ponyatovsky, E. G. T.-P. Phase diagram of the Fe-H system at temperatures to 450 C and pressures to 6.7 GPa. Scr. Metal. 16, 203–208 (1982).

Badding, J. V., Hemley, R. J. & Mao, H. K. High-pressure chemistry of hydrogen in metals: In situ study of iron hydride. Science 253, 421–424 (1991).

Yamakata, M., Yagi, T., Utsumi, W. & Fukai, Y. In situ X-ray observation of iron hydride under high pressure and high temperature. Proc. Japan Acad. 68B, 172–176 (1992).

Fukai, Y., Yamakata, M. & Yagi, T. Some high-pressure experiments on the Fe–H system. Z. Phys. Chem. 179, 119–123 (1993).

Antonov, V. E. et al. Neutron diffraction investigation of the dhcp and hcp iron hydrides and deuterides. J. Alloys Compd. 264, 214–222 (1998).

Fukai, Y., Mori, K. & Shinomiya, H. The phase diagram and superabundant vacancy formation in Fe–H alloys under high hydrogen pressures. J. Alloys Compd. 348, 105–109 (2003).

Hiroi, T., Fukai, Y. & Mori, K. The phase diagram and superabundant vacancy formation in Fe–H alloys revisited. J. Alloys Compd. 404–406, 252–255 (2005).

Pépin, C. M., Dewaele, A., Geneste, G., Loubeyre, P. & Mezouar, M. New Iron Hydrides under High Pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 265504 (2014).

Pépin, C. M., Geneste, G., Dewaele, A., Mezouar, M. & Loubeyre, P. Synthesis of FeH5: A layered structure with atomic hydrogen slabs. Science 357, 382–385 (2017).

Saitoh, H., Machida, A., Sugimoto, H., Yagi, T. & Aoki, K. P-V-T relation of the Fe-H system under hydrogen pressure of several gigapascals. J. Alloys Compd. 706, 520–525 (2017).

Stevenson, D. J. Hydrogen in the Earth’s core. Nature 268, 130–131 (1977).

Stevenson, D. J. Models of the Earth’s core. Science 214, 611–619 (1981).

Fukai, Y. & Akimoto, S. Hydrogen in the Earth’s core: experimental approach. Proc. Japan Acad. 59B, 158–162 (1983).

Fukai, Y. The iron–water reaction and the evolution of the Earth. Nature 308, 174–175 (1984).

Jephcoat, A. & Olson, P. In the inner Core of the Earth pure iron? Nature 325, 332–335 (1987).

Stixrude, L., Wasserman, E. & Cohen, R. E. Composition and temperature of Earth’s inner core. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 24729–24739 (1997).

Anderson, O. L. & Isaak, D. G. Another look at the core density deficit of Earth’s outer core. Phys. Earth Planet Inter. 131, 19–27 (2002).

Hirao, N., Kondo, T., Ohtani, E., Takemura, K. & Kikegawa, T. Compression of iron hydride to 80 GPa and hydrogen in the Earth’s inner core. Geophy. Res. Lett. 31, L06616 (2004).

Sakamaki, K. et al. Melting phase relation of FeHx up to 20 GPa: Implication for the temperature of the Earth’s core. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 174, 192–201 (2009).

Narygina, O. et al. X-ray diffraction and Mӧssbauer spectroscopy study of fcc iron hydride FeH at high pressures and implications for the composition of the Earth’s core. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 307, 409–414 (2011).

Iizuka-Oku, R. et al. Hydrogenation of iron in the early stage of Earth’s evolution. Nat Commun. 8, 14096 (2017).

Tateno, S., Hirose, K., Ohishi, Y. & Tatsumi, Y. The Structure of Iron in Earth’s Inner Core. Science 330, 359–361 (2010).

Saitoh, H., Machida, A. & Aoki, K. Synchrotron X-ray diffraction techniques for in situ measurement of hydride formation under several gigapascals of hydrogen pressure. Chin. Sci. Bull. 59, 5290–5301 (2014).

Sano-Furukawa, A. et al. Six-axis multi-anvil press for high-pressure, high-temperature neutron diffraction experiments. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 85, 113905 (2014).

Hattori, T. et al. Design and performance of high-pressure PLANET beamline at pulsed neutron source at J-PARC. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 780, 55–67 (2015).

Oishi, R. et al. Rietveld analysis software for J-PARC. Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Phys. Res. Sect. A 600, 94–96 (2009).

Fukai, Y. & Sugimoto, H. Formation mechanism of defect metal hydrides containing superabundant vacancies. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 19, 436201 (2007).

Antonov, V. E., Belash, I. T., Ponyatovskii, E. G., Thiessen, V. G. & Shiryaev, V. I. Magnetization of iron hydride. Phys. Stat. Sol. (a) 65, K43–48 (1981).

Wordel, R. et al. Mössbauer Study of Iron Hydride Produced Under High Pressure. Z. Phys. Chem. N.F. 145, 121–127 (1985).

Uchida, T., Wang, Y., Rivers, M. L. & Sutton, S. R. Stability field and thermal equation of state of ε-iron determined by synchrotron X-ray diffraction in a multianvil apparatus. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 21799–21810 (2001).

Tsujino, N. et al. Equation of state of γ-Fe: reference density for planetary cores. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 375, 244–253 (2013).

Shilstein, S. et al. The Crystal Structure of High-Pressure Hydrides. Z. Phys. Chem. N.F. 146, 129–135 (1985).

Gomi, H., Feil, Y. & Yoshino, T. The Effects of Ferromagnetism and Interstitial Hydrogen on the Physical Properties of hcp and dhcp FeHx: Implications for the Density and Magnetism of a Hydrogen-bearing Core. Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII, 1775 (2017).

Westlake, D. G. Stoichiometries and interstitial site occupation in the hydrides of zrni and other isostructural intermetallic compounds. J. Less-Common Mel. 75, 177–185 (1980).

Sugimoto, H. & Fukai, Y. Solubility of hydrogen in metals under high hydrogen pressures: Thermodynamical calculations. Acta Metall. Mater. 40, 2327–2336 (1992).

Acknowledgements

Neutron diffraction experiments were performed under proposal no. 2014B0017 at J-PARC. Synchrotron X-ray diffraction experiments were performed under proposal numbers 2015A3602 and 2016B3651 at SPring-8. This work was performed under the Inter-university Cooperative Research Program of the Institute for Materials Research, Tohoku University, proposal numbers 16K0075 and 17K0018, and supported partially by the Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research, grant numbers 24241032, 25220911 and 18H05224 of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. We thank T. Yagi and H. Kagi for their polite discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M., H.S., T.H., A.S.-F. and K.F. performed the high-pressure neutron diffraction experiments. H.S. performed the high-pressure X-ray diffraction experiments. T.S. and S.O. prepared AlD3 and AlH3. A.M. and K.A. analyzed the neutron and X-ray diffraction data. A.M. and K.A. wrote the manuscript. K.A. directed this study.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Machida, A., Saitoh, H., Hattori, T. et al. Hexagonal Close-packed Iron Hydride behind the Conventional Phase Diagram. Sci Rep 9, 12290 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48817-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48817-7

This article is cited by

-

Refinement of the Crystal Structure of Low-Carbon Polycrystalline AISI 420 Martensitic Steel (C = 0.15%)

Brazilian Journal of Physics (2023)

-

Chemical species of localized fe atoms in solid hydrogen using in-beam mössbauer spectroscopy

Hyperfine Interactions (2022)

-

Compressional wave velocity for iron hydrides to 100 gigapascals via picosecond acoustics

Physics and Chemistry of Minerals (2022)

-

Behavior of light elements in iron-silicate-water-sulfur system during early Earth’s evolution

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Hydrogenation treatment under several gigapascals assists diffusionless transformation in a face-centered cubic steel

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.