Abstract

Antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes which confer resistance to antibiotics from human/animal sources are currently considered a serious environmental and a public health concern. This problem is still little investigated in aquatic environment of developing countries according to the different climatic conditions. In this research, the total bacterial load, the abundance of relevant bacteria (Escherichia coli (E. coli), Enterococcus (Ent), and Pseudomonas), and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs: blaOXA-48, blaCTX-M, sul1, sul2, sul3, and tet(B)) were quantified using Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) in sediments from two rivers receiving animal farming wastewaters under tropical conditions in Kinshasa, capital city of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Human and pig host-specific markers were exploited to examine the sources of contamination. The total bacterial load correlated with relevant bacteria and genes blaOXA-48, sul3, and tet(B) (P value < 0.01). E. coli strongly correlated with 16s rDNA, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas spp., blaOXA-48, sul3, and tet(B) (P value < 0.01) and with blaCTX-M, sul1, and sul2 at a lower magnitude (P value < 0.05). The most abundant and most commonly detected ARGs were sul1, and sul2. Our findings confirmed at least two sources of contamination originating from pigs and anthropogenic activities and that animal farm wastewaters didn’t exclusively contribute to antibiotic resistance profile. Moreover, our analysis sheds the light on developing countries where less than adequate infrastructure or lack of it adds to the complexity of antibiotic resistance proliferation with potential risks to the human exposure and aquatic living organisms. This research presents useful tools for the evaluation of emerging microbial contaminants in aquatic ecosystems which can be applied in the similar environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global consumption of antibiotics between 2000 and 2015 has increased by approximately by 69%; that’s more than 4% increase annually. The spike in the consumption rate is quite alarming and has to be addressed1. Some countries have achieved a restriction on the sales of antibiotic and limited it to prescriptions by medical professionals. However, the sales of antibiotics in the rest of the world remains unmonitored and effortlessly accessible. The overuse of antibiotics and their subsequent poorly managed release to the environment especially aquatic systems have been linked with the development of antibiotic resistant characteristics2,3,4,5.

Wastewater effluent and effluent from animal farming and slaughter houses, where livestock consume staggering amounts of antibiotics for growth promotion, remain the most serious sources of antibiotic resistant genes. Even when such effluent goes under treatment, there’s more than sufficient evidence that ARGs remain detectable6,7,8. ARGs were found to remain detectable via molecular methods in the effluents from urban and hospital wastewater treatment plants7,9. The release of such contamination into the environment presents a great risk to the public health10,11,12,13.

The study of faecal contamination and ARGs outside clinical settings has gained momentum in the scientific community over last number of decades14,15,16,17,18. The assessment of the propagation and persistence of ARGs amongst all bacteria in general and human and animal pathogens especially in the environment will provide control measures to limit the harm of such genetic materials8,19,20,21,22. Waterbodies receiving typically wastewater contain a relatively high content of metals and provide a suitable environment for the selective pressure for antibiotic resistance and horizontal gene transfer (HGT) especially in warmer climates23. The occurrence of heavy metals in a given environment has shown to exert a selective pressure for antibiotic resistance bacteria. Moreover, low concentration of toxic metals have been shown to induce the conjugative transfer of ARGs24,25. However, sediments retain bacteria and antibiotics at a much higher scale than water and are less influenced by fluid dynamics. Therefore, sediments have been identified as reservoir of faecal indicator bacteria (FIB) and ARGs26,27,28 in aquatic environment according to the different climatic conditions.

The untreated/partial treated wastewater treatment plants (WWTP), urban, hospital, animal farms and industrial effluent waters can be considered as the main sources contributing to the dissemination of emerging contaminants (such as heavy metals, pathogens, ARGs, nutrients) into the aquatic environment. In developing countries, little information is available on the assessment of these contaminants in river receiving systems and few studies have been conducted to evaluate the effects of untreated hospital and urban effluent waters under tropical conditions including previous publications from our lab23,29. Moreover, studies on the contribution of animal farming to the proliferation of pathogens, ARGs in Sub-Saharan African rivers are quite limited. Consequently, in this study, we aimed to investigate the occurrence of ARGs and relevant bacteria marker genes in two different river systems in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo which are receiving effluent from animal farms to assess the contribution of the farms in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. Also, we confirmed the source of contamination via detection of host-specific genetic markers. The assessment is based on Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) of ARGs (blaOXA-48, blaCTX-M, Sul1, Sul2, Sul3, and tet(B)) and relevant bacteria marker genes (Escherichia coli, Enterococcus, and Pseudomonas spp.) and PCR of host-specific markers (humans and pigs). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on the impact of animal farming on the propagation of ARGs and relevant bacteria in a central African region and specifically in the city of Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Materials and Methods

Sampling sites

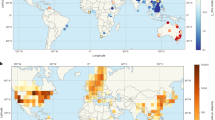

Two urban rivers were selected in the municipalities of Masina and Kintambo in the capital city of Kinshasa (DR Congo) to assess the impact of animal farming on the dissemination of ARGs (Fig. 1). Kinshasa is around 9,965 km2 and home to more than 11 million inhabitant. Each year Kinshasa receives a significant amount of people displaced by conflict, which contributes to the uncontrollable growth of urbanization in this Sub-Saharan Capital. Infrastructure, sanitation, and drainage system suffer a heavy load due to this growth that’s unaccounted for. Sampling procedure was similar to our previous publications8,23,29. The sampling took place in October, 2018. The letters K and M will be used to refer to Kintambo and Masina respectively in the text and figures. In each urban river, sediment samples were taken directly from the animal farms outlets which grew some cattle but mainly pigs (K eff and M eff) (Table 1) as well as downstream (K down and M down) and upstream (K up and M up) to the effluent discharge. Additionally, sediment samples were collected from Lake Ma Vallée to serve as controls because the lake doesn’t receive any wastewater effluents of any kind. Samples subsequently are preserved in an ice box at 4 °C before being shipped to the Department F.-A. Forel for Environmental and Aquatic Sciences at the University of Geneva and analyzed within two weeks.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from a mass of about 0.2 g of each of the samples according to the manufacturer’s protocol of PureLink Microbiome DNA purification kit (Invitrogen). The exact mass, from which the DNA was extracted, was used for a more precise mean of DNA quantification. Extracted DNA was kept at −20 C until needed for downstream applications. The extracted DNA quality was examined by spectrophotometer (UV/VIS Lambda 365, PerkinElmer, Massachusetts, USA) using the 260/280 ratio which ranged between 1.74 and 1.92. The extraction volume was 50 μL and the concentrations ranged between 13.16 ng μL−1 and 54.66 ng μL−1.

Faecal source tracking

The presence of host-specific markers of interest within the extracted genomic DNA was investigated using Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) with specific primer pairs for each of the human and pig markers (Table 2). Each PCR reaction was done in 50 µL volume which contains 5 µL of 10X DreamTaq buffer, 5 µL of 2 mM dNTP mix, 2.5 µl of 10 mM of each primer, 30 µL of molecular grade water, 0.25 µL of DreamTaq polymerase (5U/µL), and 5 µL of genomic DNA extracts. Biometra TOne thermocycler (Labgene) was used to perform an initial polymerase activation stage of 3 minutes followed by thirty cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, appropriate annealing temperature (Tm) for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min and a final 5 min extension at 72 °C. The PCR products were subsequently analyzed via 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. Samples with clear bands and a corresponding length to the marker of interest were considered positive.

Quantification of ARGs and relevant bacteria markers

Primer pairs targeting different and specific genes for the qPCR have different efficiencies of amplification and varying annealing temperatures (Table 3). The quantification of the ARGs and the 16S rDNA was performed using SensiFAST SYBR No-Rox kit in an Eco qPCR System (Illumina) with a mix of 2 µL of 2X SensiFAST SYBR No-Rox mix, final concentration of 0.4 µM of primers, 1 µL of extracted DNA and molecular grade water up to 5 µL. The following cycling conditions were applied: 95 °C of polymerase activation for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s, optimal annealing temperature for 10 s, and extension at 72 °C for 10 s, and a final melting curve analysis. The interpretation of the qPCR results has been described in our previous publications8,29. In brief, six different dilutions of positive controls of known concentrations were used to construct the standard curve. Any samples with Ct value higher than or equal to negative control or the most diluted concentration of the standard curve were considered below the detection limit.

Statistical analysis

The R software version (3.5.2) was utilized to generate Principle Component Analysis (PCA) by inputting the absolute copy numbers of investigated markers and genes per gram of dry sediment30. The R package (Ade4) was used to generate the statistical data. The copy numbers were scaled to standardize the variance of the variables prior to the PCA analysis31. Also, the R software was utilized to produce Pearson Correlations Matrix at 95% confidence level.

Results and Discussion

PCR assays for source tracking

Faecal contamination originating from pig is occurring in all studied sites except for the samples from Lake Ma Vallée, the control site (Table 4). In the river from Masina, all sites were positive for contamination originating from pig feces; also, anthropogenic activities were detected upstream and downstream but not in the animal farm effluent. Similarly, in Kintambo, all sites were contaminated by pigs waste and contamination from human origins occurs upstream and downstream but not in the effluent from animal farming. Downstream and upstream of the effluents are affected by anthropogenic activities, which isn’t surprising due to the uncontrolled urbanization of Kinshasa and the unmanaged waste release. The control site from Lake Ma Vallée were negative for human and pig contamination. To summarize, all the sampling sites with the exception of Lake Ma Vallée were contaminated by bacteria originating from pigs.

Quantification of ARGs by quantitative PCR (qPCR)

The absolute abundances of 16s rDNA are illustrated in (Fig. 2). The 16s rDNA abundances are expressed in log10 of copies per 1 g of dry sediment for a clearer presentation. The abundances of 16s rDNA varies significantly between Masina and Kintambo (p value < 0.01). The riverbed sediment from Masina housed significantly more 16s rDNA copies than Kintambo and the control site. The abundance ranged from its lowest at 8.13 × 1010 (control) to its highest in Masina (M up) upstream of the effluent at 5.35 × 1011 copies per gram of dry sediment, which isn’t surprising considering all the bacterial load brought in from urban wastewater and various anthropogenic activities compared to the control site. On average the sampling sites in Masina has 3.7 and 5.7 times the bacterial load as Kintambo and the control site respectively.

Normalized abundances of relevant bacteria marker genes is expressed in log10 total copy numbers per copies of 16s rDNA (Fig. 3). In a comparison between Masina, Kintambo, and the control sites, the average abundances of E. coli, Enterococcus and Pseudomonas in folds were 11.1 and 3.4, 30 and 1.9, and 5.8 and 5.4 respectively higher in Masina than the control site and Kintambo respectively. The relative abundance of E. coli, Enterococcus and Pseudomonas variations were significant between Masina, Kintambo and the control site (P value < 0.05); however, the variation upstream and downstream from the animal farm effluent weren’t which leads to the conclusion that the animal farming effluent didn’t contribute specifically to the degradation of the microbial quality of the rivers. On a different note, E. coli and Enterococcus relative abundances are higher in Masina and Kintambo than of the control site which concludes that both municipalities are contributing to the degradation of the microbial quality of the surface water. Masina district is a home to about four times the population of Kintambo which could attribute the higher copy numbers of all investigated markers and genes32. The contribution of wastewater investigated in this study site isn’t distinguishable when comparing downstream and upstream which could be attributed to a number of factors such as inadequate infrastructure and furrow release of wastewater. However, in the developed world where infrastructure is integral part of cities and even towns, the contribution of wastewater is noticeable and significant9.

Sulfonamides, and tetracycline resistance genes were selected for this study because of the usage of their perspective antibiotics in animal farming worldwide. Both tetracycline and sulfonamides are heavily used in the veterinary medicine to treat microbial infections and also as feed additives at lower concentrations to promote growth in livestock33,34. For instance, in 2012, the annual consumption of tetracycline in the United States exceeded 5954 tons35. Also, betalactam resistant genes were selected because more than half of the antibiotic prescribed to humans are betalactams36.

The relative abundances of blaOXA-48 and tet (B) are significantly different between Masina, Kintambo and the control site (p value < 0.05) but not blaCTX-M (Fig. 4). blaOXA-48 and tet (B) aren’t detectable in the control site; however, blaCTX-M was ubiquitous and detectable in all sites even in the control site that is expected as blaCTX-M is considered one of the most widespread ARGs around the world37. Therefore, both municipalities are contributing to the spread of antibiotic resistant but not animal farming specifically. Moreover, tet (B) wasn’t detected in effluent from the animal farm in Kintambo.

The relative abundance of sulfonamide resistance gene (sul1, sul2, and sul3) is illustrated in (Fig. 5). The abundance in all the sites of sul1 was the highest followed by sul2 and finally by sul3. Sul1 and sul2 weren’t significantly different between Masina and Kintambo. However, all the sulfonamide resistance genes weren’t detectable in the control sites. This means that again that both municipalities are contributing to the spread of ARGs.

Sul1 and sul2 are the most abundant ARGs reported in this study which could be attributed to lack of infrastructure in the study sites and the overwhelming agricultural runoff from farms using manure as demonstrated in several studies performed in similar environment; e.g., in a study38, soils were supplied with antibiotic-free manure and with manure containing sulfonamides (10 or 100 ppm sulfadiazine in soil); Copy number of sul1 and sul2 increased with the application of the manure and increased even higher with the addition of sulfadiazine compare to the control soil. In a similar study conducted in China39, soils receiving compost and manure from pig farms showed a median ARGs enrichment of 192 times that of the control soils. In Canada and the United States40, research samples were soils receiving compost and manure from antibiotic-free animal farms and farms using subtherapeutic quantities of antibiotics; tetracycline resistance genes were only detected in isolates from farms using antibiotics for growth promotion.

Sediments are known to provide safe haven for bacteria by providing nutrient essential for growth and also provides a protection from degradation by sunlight41,42. The persistence of bacteria accompanied by Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) leads to the enrichment and proliferation of ARGs43,44,45. All these factors present a risk to the public health and further degradation of surface water quality.

Statistical analysis

The data from the absolute abundances of the 16s rDNA, relevant bacteria markers, and ARGs per gram of dry sediments was processed to perform a principle component analysis (Fig. 6). The data was scaled to standardize the variance amongst the variables to eliminate the dominance of certain variables e.g. 16s rDNA in this case. The Principle component analysis is utilized in this study to illustrate the resemblance of bacterial composition in the study sites. The first principle accounted for 52.2% of the total variance and the second principle component accounted for 14.1%, which make a grand total of 66.3%. The correlation between the genes used in this study is quite clear from (Fig. 6) with a range of magnitudes. According to the analysis of variance (ANOVA), there wasn’t a significant different within groups. Therefore, the PCA and cluster analysis was utilized to illustrate between group analysis (BGA) and not within group analysis (WGA). Each municipality is forming its own cluster suggesting that Masina, Kintambo and the control site are distinctly different from one another. However, Kintambo and the control site clusters are closer to each other, which means that Kintambo is less contaminated than Masina which further backs up our earlier findings from the ARGs abundance comparisons.

Also, a Pearson correlation matrix was constructed to demonstrate the linear relationship between all the variables and its degree in a form of P value (Table 5). 16s rDNA is positively correlated with E. coli, Pseudomonas, Enterococcus, blaOXA-48, sul3, and tet (B) at a significance level of 0.01 and coefficients between 0.45 and 0.89. Moreover, E. coli is positively correlated with all the genes at the 0.01 significance level with the exception of blaCTX-M, sul1 and sul2 at the 0.05 level. Enterococcus and Pseudomonas don’t correlate with each other; however, they share the same correlation profile with all the other genes with only a single difference. Enterococcus and Pseudomonas positively correlate 16s rDNA, E. coli, sul3, and tet(B) at the 0.01 level and with blaOXA, 0.05 and 0.01 level for Enterococcus and Pseudomonas respectively. In the next part of this paragraph, only the relationship between ARGs will be discussed to avoid repetition. BlaOXA-48 correlates with sul1, sul3, and tet(B) at the 0.01 level and blaCTX-M only correlates with one other ARG which is sul3. Tet (B) correlates with all the genes are at the 0.01 level with the exception of blaCTX-M and sul1. The persistence of ARGs has been long linked to the occurrence of faecal indicator bacteria e.g. E. coli and Enterococcus46,47. Also, other studies showed that the tropical climate such as our study sites further aids the efficiency of HGT which ultimately leads to the persistence and propagation of ARGs which represents a major public health issue48,49,50. The strong correlation of ARGs with E. coli support the fecal origin of these genes.

Conclusion

This research investigates the occurrence trends of relevant bacteria and ARGs in two different rivers receiving effluent waters from animal farming under tropical conditions. These rivers serve as a basic network for human and animal consumption as well as irrigation for fresh urban produces. The findings from this study demonstrated that such aquatic systems can act as a reservoir of indicator bacteria (Escherichia coli, Enterococcus and Pseudomonas), and antibiotic resistance genes (blaOXA-48, blaCTX-M, sul1, sul2, sul3, and tet(B)) which could pose a further potential threat to the environment and human health.

On the other hand, the presence of higher values of relevant bacteria and ARGs in sediment samples located upstream of studied sites indicates that the animal farming wastewaters are not the only source of deterioration of the quality of studied rivers by investigated indicator bacteria and ARGs. Additionally, the faecal source tracking shows a variety of contamination originating from both pigs and anthropogenic activities.

The study concludes that effluent from animal farms aren’t the exclusive contributors in the propagation and the spread of ARGs but also anthropogenic activities. The lack of infrastructure, the furrow release of untreated wastewater, the unmonitored urbanization of Kinshasa, open defecation, septic tanks, over-the-counter antibiotics consumption and absence of antibiotics use regulation in humans, animals as well as for other agricultural purposes are probable sources of deterioration of the quality of the rivers. This study provides significant information indicating that sediments from tropical river receiving system could act as a potential reservoir of bacterial populations from human and animal sources. Thus, we suggest a well-monitored plan for the reduction of antibiotic consumption in animal farming to relieve the pressure applied for the selection of antibiotic resistance. The treatment or at least the partial treatment of the effluent will decrease bacteria of faecal origin that contribute to the propagation and persistence of such genes. Also, the uncontrolled urbanization in the Sub-Saharan Capital Cities and the lack of adequate infrastructure contribute to the spread of ARGs and has to be addressed.

Ethic statement

We confirm that the field studies and sampling did not involve misunderstanding. The funder has no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Klein, E. Y. et al. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115, E3463–E3470, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1717295115 (2018).

Al-Taani, G. M. et al. Longitudinal point prevalence survey of antibacterial use in Northern Ireland using the European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC) PPS and Global-PPS tool. Epidemiol Infect 146, 985–990, https://doi.org/10.1017/S095026881800095x (2018).

Carlet, J. et al. Society’s failure to protect a precious resource: antibiotics. Lancet 378, 369–371, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60401-7 (2011).

Schar, D., Sommanustweechai, A., Laxminarayan, R. & Tangcharoensathien, V. Surveillance of antimicrobial consumption in animal production sectors of low- and middle-income countries: Optimizing use and addressing antimicrobial resistance. Plos Med 15, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002521 (2018).

Wu, Y. L. et al. An 8-year point-prevalence surveillance of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in a tertiary care teaching hospital in China. Epidemiol Infect 147, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268818002856 (2019).

Baquero, F. From pieces to patterns: evolutionary engineering in bacterial pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol 2, 510–518, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro909 (2004).

Al-Jassim, N., Ansari, M. I., Harb, M. & Hong, P. Y. Removal of bacterial contaminants and antibiotic resistance genes by conventional wastewater treatment processes in Saudi Arabia: Is the treated wastewater safe to reuse for agricultural irrigation? Water Res 73, 277–290, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2015.01.036 (2015).

Devarajan, N. et al. Occurrence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Bacterial Markers in a Tropical River Receiving Hospital and Urban Wastewaters. Plos One 11, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0149211 (2016).

McConnell, M. M. et al. Sources of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in a Rural River System. J Environ Qual 47, 997–1005, https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq.2017.12.0477 (2018).

Dang, H., Ren, J., Song, L., Sun, S. & An, L. Diverse tetracycline resistant bacteria and resistance genes from coastal waters of Jiaozhou Bay. Microb Ecol 55, 237–246, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-007-9271-9 (2008).

Eramo, A., Medina, W. R. M. & Fahrenfeld, N. L. Viability-based quantification of antibiotic resistance genes and human fecal markers in wastewater effluent and receiving waters. Sci Total Environ 656, 495–502, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.325 (2019).

Hernandez, F. et al. Occurrence of antibiotics and bacterial resistance in wastewater and sea water from the Antarctic. J Hazard Mater 363, 447–456, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.07.027 (2019).

Li, B., Qiu, Y., Zhang, J., Liang, P. & Huang, X. Conjugative potential of antibiotic resistance plasmids to activated sludge bacteria from wastewater treatment plants. Int Biodeter Biodegr 138, 33–40, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2018.12.013 (2019).

Bernhard, A. E. & Field, K. G. Identification of nonpoint sources of fecal pollution in coastal waters by using host-specific 16S ribosomal DNA genetic markers from fecal anaerobes. Appl Environ Microb 66, 1587–1594, https://doi.org/10.1128/Aem.66.4.1587-1594.2000 (2000).

Bernhard, A. E. & Field, K. G. A PCR assay To discriminate human and ruminant feces on the basis of host differences in Bacteroides-Prevotella genes encoding 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol 66, 4571–4574 (2000).

Barrios, M. E., Fernandez, M. D. B., Cammarata, R. V., Torres, C. & Mbayed, V. A. Viral tools for detection of fecal contamination and microbial source tracking in wastewater from food industries and domestic sewage. J Virol Methods 262, 79–88, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2018.10.002 (2018).

Wu, J. Y. Linking landscape patterns to sources of water contamination: Implications for tracking fecal contaminants with geospatial and Bayesian approaches. Sci Total Environ 650, 1149–1157, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.087 (2019).

Yin, H. L. et al. Identification of sewage markers to indicate sources of contamination: Low cost options for misconnected non-stormwater source tracking in stormwater systems. Sci Total Environ 648, 125–134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.448 (2019).

Osinska, A., Korzeniewska, E., Harnisz, M. & Niestepski, S. Quantitative Occurrence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes among Bacterial Populations from Wastewater Treatment Plants Using Activated Sludge. Appl Sci-Basel 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/app9030387 (2019).

Petrovich, M. L., Rosenthal, A. F., Griffin, J. S. & Wells, G. F. Spatially resolved abundances of antibiotic resistance genes and intI1 in wastewater treatment biofilms. Biotechnol Bioeng 116, 543–554, https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.26887 (2019).

Devarajan, N. et al. Hospital and urban effluent waters as a source of accumulation of toxic metals in the sediment receiving system of the Cauvery River, Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu, India. Environ Sci Pollut R 22, 12941–12950, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-015-4457-z (2015).

Kilunga, P. I. et al. The impact of hospital and urban wastewaters on the bacteriological contamination of the water resources in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. J Environ Sci Heal A 51, 1034–1042, https://doi.org/10.1080/10934529.2016.1198619 (2016).

Devarajan, N. et al. Antibiotic resistant Pseudomonas spp. in the aquatic environment: A prevalence study under tropical and temperate climate conditions. Water Res 115, 256–265, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2017.02.058 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. Sub-inhibitory concentrations of heavy metals facilitate the horizontal transfer of plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance genes in water environment. Environ Pollut 237, 74–82, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.01.032 (2018).

Baker-Austin, C., Wright, M. S., Stepanauskas, R. & McArthur, J. V. Co-selection of antibiotic and metal resistance. Trends Microbiol 14, 176–182, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2006.02.006 (2006).

Haller, L., Amedegnato, E., Pote, J. & Wildi, W. Influence of Freshwater Sediment Characteristics on Persistence of Fecal Indicator Bacteria. Water Air Soil Poll 203, 217–227, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-009-0005-0 (2009).

Haller, L. et al. Composition of bacterial and archaeal communities in freshwater sediments with different contamination levels (Lake Geneva, Switzerland). Water Research 45, 1213–1228, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2010.11.018 (2011).

Pote, J., Bravo, A. G., Mavingui, P., Ariztegui, D. & Wildi, W. Evaluation of quantitative recovery of bacterial cells and DNA from different lake sediments by Nycodenz density gradient centrifugation. Ecol Indic 10, 234–240, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2009.05.002 (2010).

Laffite, A. et al. Hospital Effluents Are One of Several Sources of Metal, Antibiotic Resistance Genes, and Bacterial Markers Disseminated in Sub-Saharan Urban Rivers. Front Microbiol 7, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01128 (2016).

Team, R. C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2012).

Dray, S. & Dufour, A.-B. The ade4 Package: Implementing the Duality Diagram for Ecologists. 2007 22, 20%J Journal of Statistical Software, https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v022.i04 (2007).

Population, C. The population of the city districts and communes of Kinshasa, http://www.citypopulation.de/php/congo-kinshasa-admin.php (2004).

Callaway, T. R. et al. Ionophores: their use as ruminant growth promotants and impact on food safety. Curr Issues Intest Microbiol 4, 43–51 (2003).

Sarmah, A. K., Meyer, M. T. & Boxall, A. B. A. A global perspective on the use, sales, exposure pathways, occurrence, fate and effects of veterinary antibiotics (VAs) in the environment. Chemosphere 65, 725–759, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.03.026 (2006).

Van Boeckel, T. P. et al. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. P Natl Acad Sci USA 112, 5649–5654, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1503141112 (2015).

Lachmayr, K. L., Kerkhof, L. J., DiRienzo, A. G., Cavanaugh, C. M. & Ford, T. E. Quantifying Nonspecific TEM beta-Lactamase (bla(TEM)) Genes in a Wastewater Stream. Appl Environ Microb 75, 203–211, https://doi.org/10.1128/Aem.01254-08 (2009).

Canton, R., Jose, M. G. A. & Galan, J. C. CTX-M enzymes: origin and diffusion. Front Microbiol 3, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2012.00110 (2012).

Heuer, H. et al. Accumulation of Sulfonamide Resistance Genes in Arable Soils Due to Repeated Application of Manure Containing Sulfadiazine. Appl Environ Microb 77, 2527–2530, https://doi.org/10.1128/Aem.02577-10 (2011).

Zhu, Y. G. et al. Diverse and abundant antibiotic resistance genes in Chinese swine farms. P Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 3435–3440, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1222743110 (2013).

Ghosh, S. & LaPara, T. M. The effects of subtherapeutic antibiotic use in farm animals on the proliferation and persistence of antibiotic resistance among soil bacteria. Isme J 1, 191–203, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2007.31 (2007).

Kragh, T., Sondergaard, M. & Tranvik, L. Effect of exposure to sunlight and phosphorus-limitation on bacterial degradation of coloured dissolved organic matter (CDOM) in freshwater. Fems Microbiol Ecol 64, 230–239, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00449.x (2008).

Laliberte, P. & Grimes, D. J. Survival of Escherichia-Coli in Lake Bottom Sediment. Appl Environ Microb 43, 623–628 (1982).

Borjesson, S. et al. Quantification of genes encoding resistance to aminoglycosides, beta-lactams and tetracyclines in wastewater environments by real-time PCR. Int J Environ Heal R 19, 219–230, https://doi.org/10.1080/09603120802449593 (2009).

Chagas, T. P. G. et al. Multiresistance, beta-lactamase-encoding genes and bacterial diversity in hospital wastewater in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Appl Microbiol 111, 572–581, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05072.x (2011).

Chen, B. et al. Class 1 Integrons, Selected Virulence Genes, and Antibiotic Resistance in Escherichia coli Isolates from the Minjiang River, Fujian Province, China. Appl Environ Microb 77, 148–155, https://doi.org/10.1128/Aem.01676-10 (2011).

Calero-Caceres, W., Mendez, J., Martin-Diaz, J. & Muniesa, M. The occurrence of antibiotic resistance genes in a Mediterranean river and their persistence in the riverbed sediment. Environmental Pollution 223, 384–394, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.01.035 (2017).

Colomer-Lluch, M., Imamovic, L., Jofre, J. & Muniesa, M. Bacteriophages Carrying Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Fecal Waste from Cattle, Pigs, and Poultry. Antimicrob Agents Ch 55, 4908–4911, https://doi.org/10.1128/Aac.00535-11 (2011).

Jain, R., Rivera, M. C., Moore, J. E. & Lake, J. A. Horizontal gene transfer accelerates genome innovation and evolution. Mol Biol Evol 20, 1598–1602, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msg154 (2003).

Neilson, J. W. et al. Frequency of Horizontal Gene-Transfer of a Large Catabolic. Plasmid (Pjp4) in Soil. Appl Environ Microb 60, 4053–4058 (1994).

Yue, W. F., Du, M. & Zhu, M. J. High Temperature in Combination with UV Irradiation Enhances Horizontal Transfer of stx2 Gene from E. coli O157:H7 to Non-Pathogenic E. coli. Plos One 7, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031308 (2012).

Dick, L. K. et al. Host distributions of uncultivated fecal Bacteroidales bacteria reveal genetic markers for fecal source identification. Appl Environ Microb 71, 3184–3191, https://doi.org/10.1128/Aem.71.6.3184-3191.2005 (2005).

Ovreas, L., Forney, L., Daae, F. L. & Torsvik, V. Distribution of bacterioplankton in meromictic Lake Saelenvannet, as determined by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified gene fragments coding for 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol 63, 3367–3373 (1997).

Chern, E. C., Siefring, S., Paar, J., Doolittle, M. & Haugland, R. A. Comparison of quantitative PCR assays for Escherichia coli targeting ribosomal RNA and single copy genes. Lett Appl Microbiol 52, 298–306, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.03001.x (2011).

Bergmark, L. et al. Assessment of the specificity of Burkholderia and Pseudomonas qPCR assays for detection of these genera in soil using 454 pyrosequencing. FEMS Microbiol Lett 333, 77–84, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02601.x (2012).

Ryu, H. et al. Development of quantitative PCR assays targeting the 16S rRNA genes of Enterococcus spp. and their application to the identification of enterococcus species in environmental samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 79, 196–204, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02802-12 (2013).

Pei, R. T., Kim, S. C., Carlson, K. H. & Pruden, A. Effect of River Landscape on the sediment concentrations of antibiotics and corresponding antibiotic resistance genes (ARG). Water Research 40, 2427–2435, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2006.04.017 (2006).

Heuer, H. & Smalla, K. Manure and sulfadiazine synergistically increased bacterial antibiotic resistance in soil over at least two months. Environ Microbiol 9, 657–666, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01185.x (2007).

Nemec, A., Dolzani, L., Brisse, S., van den Broek, P. & Dijkshoorn, L. Diversity of aminoglycoside-resistance genes and their association with class 1 integrons among strains of pan-European Acinetobacter baumannii clones. J Med Microbiol 53, 1233–1240, https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.45716-0 (2004).

Poirel, L., Walsh, T. R., Cuvillier, V. & Nordmann, P. Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemase genes. Diagn Micr Infec Dis 70, 119–123, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.12.002 (2011).

Fujita, S. et al. Rapid Identification of Gram-Negative Bacteria with and without CTX-M Extended-Spectrum beta-Lactamase from Positive Blood Culture Bottles by PCR Followed by Microchip Gel Electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol 49, 1483–1488, https://doi.org/10.1128/Jcm.01976-10 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology, the Saudi Arabian Cultural Mission (Scholarship no. 11432) and the Open Acess publication Funds of University of Geneva.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M.A.S., A.L. and J.P. conceived and designed research; D.M.A.S. and A.L. performed research and laboratory analysis; all authors analyzed data, wrote the paper, have read, reviewed and approved the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Salah, D.M.M., Laffite, A. & Poté, J. Occurrence of Bacterial Markers and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Sub-Saharan Rivers Receiving Animal Farm Wastewaters. Sci Rep 9, 14847 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51421-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51421-4

This article is cited by

-

Occurrence of toxic metals and their selective pressure for antibiotic-resistant clinically relevant bacteria and antibiotic-resistant genes in river receiving systems under tropical conditions

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2022)

-

Methods to alleviate the inhibition of sludge anaerobic digestion by emerging contaminants: a review

Environmental Chemistry Letters (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.