Abstract

By taking advantage of seeded polymer nanoparticles and strong photo energy absorption, we report CO2 laser impacting on water to produce cavitation at the air/water interface. Using a high-speed camera, three regimes (no cavitation, cavitation, and pseudo-cavitation) are identified within a broad range of nanoparticles concentration and size. The underlying correlation among cavitation, nanoparticles and temperature is revealed by the direct observation of spatiotemporal evolution of temperature using a thermal cameral. These findings indicate that nanoparticles not only act as preexisted nuclei to promote nucleation for cavitation, but also likely affect temperature to change the nucleation rate as well. Moreover, by exploiting a compound hexane/water interface, a novel core-shell cavitation is demonstrated. This approach might be utilized to attain and control cavitations by choosing nanoparticles and designing interfaces while operating at a lower laser intensity, for versatile technological applications in material science and medical surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the seminal work by Lord Rayleigh in 19171, cavitation has been extensively studied in various forms, such as flow cavitation, acoustic cavitation, and laser-induced cavitation2,3,4, offering diverse applications in microfluidic manipulation5, surface cleaning6,7, nanomaterials synthesis8,9, and medical treatment10. In particular, lasers impacting on liquids, ranging from a single droplet11,12 to soft biological tissues13, can generate vapor explosions and cavitation. Due to the intense laser-tissue interaction, lasers offer the potential to precisely manipulate or locally destroy biological tissues for many clinical applications including lithotripsy, tumor removal and neurosurgery13,14,15. Specifically, an ultrafast infrared laser can be selectively absorbed by water in the tissue to generate a rapid ablation or cutting process, holding promise for minimally invasive surgery down to the single-cell level16.

Generally, laser-induced cavitation is produced either by cascading ionization through focusing of high intensity short-pulsed lasers into transparent liquids (optical cavitation), or by direct heating due to strong absorption through irradiating long-exposure or continuous-wave lasers in highly absorbing liquids (thermocavitation)17,18. Recently, this cavitation has been manipulated into complex geometries while being encapsulated inside microchannels of PDMS devices19.

Moreover, cavitation can be controlled by seeded nanoparticles (NPs) immersed in water20,21. For example, in acoustic cavitation, polymer NPs (polyethylene) serve as nuclei to promote heterogeneous nucleation, while SiO2 NPs form stable bonds with water molecules to suppress cavitation. Metallic NPs (gold or aluminum) under incident light cause local boiling due to plasmonic resonance, generating vapor cavitation for solar energy harvesting22,23,24,25.

In this paper, by taking advantage of seeded polymer NPs and the strong photo energy absorption of water at the infrared wavelength, we report a CO2 laser impacting on water to produce cavitation at the air/water interface. Three regimes (no cavitation, cavitation, and pseudo-cavitation) are identified within a broad range of NP concentration and size. This cavitation allows the direct observation of spatiotemporal evolution of temperature, revealing the underlying correlation between cavitation and temperature. Moreover, by exploiting a compound hexane/water interface, a novel core-shell cavitation is demonstrated.

Results

Nanoparticle effect

Cavitation promoted by NPs

Since water has a strong absorption peak of 832 cm−1 at the wavelength of 10.6 μm26, resulting in a short penetration depth down to 12 μm, the energy is dramatically attenuated when CO2 laser impacts on water (Fig. 1a). Arising from this strong photo-thermal effect, water is rapidly heated up to generate explosive vaporization27,28. As the laser intensity is about 5 × 102 W/cm2, much lower than the typical ablation threshold (~104 W/cm2), no cavitation but only vaporization is observed from high speed imaging (Phantom V611, Fig. 1b).

Observation of interfacial cavitation promoted by NPs. (a) Sketch of the produced cavitation during laser impacting on water. (b) No cavitation in distilled water (Plaser = 35 W, 2R0 = 3 mm). (c) High-speed images of cavitation with seeding NPs (dNP = 200 nm and CNP = 6 × 10−6). (d) Snapshots for pseudo-cavitation at higher concentration (CNP = 6 × 10−4), the white line for the air/water interface and the red line for the indentation. (e) Dynamics of cavitation during the growth and collapse stage for CNP = 6 × 10−6. (f) A power-law dependence of radius on time with an exponent α = 1/3 (\(\tilde{R}\propto {\tilde{t}}^{\alpha }\), black line) for various dNP and CNP.

When the seeding polymer NPs (the diameter dNP = 200 nm) are introduced into the distilled water at CNP = 6 × 10−6 (the volume concentration, the ratio between the total NPs volume and water volume), cavitation is generated at the air/water interface at the same laser intensity in high-speed imaging [Fig. 1c and Supplementary Video (SV) 1]. At a much higher CNP = 6 × 10−4 (Fig. 1d and SV 1), water becomes opaque, and no cavitation appears at the air/water interface (the white line). Instead, an unexpected indentation (the red line) is observed with a small size much less than the beam size, which is referred to as pseudo-cavitation.

Cavitation dynamics

At an NP concentration of CNP = 6 × 10−6 (Fig. 1c), the interfacial cavitation with a hemi-spherical shape expands explosively within milliseconds, consistent with the capillary time scale \({\tau }_{0}={(\rho {R}_{0}^{3}/\gamma )}^{1/2}\approx 4\,{\rm{ms}}\), where ρ is the density of water, γ is the surface tension of water, and R0 is the radius of laser beam (2R0 = 3 mm). Once the radius (R) is increased beyond R0, the growth is gradually slowed down due to hydrostatic pressure, then cavitation is contracted quickly undergoing large deformations (the last two snapshots of Fig. 1c). The corresponding time-dependent radius R(t) is presented in Fig. 1e.

By a dimensional analysis \([\tilde{R}=R(t)/{R}_{0},\tilde{t}=t/{t}_{0},R({t}_{0})={R}_{0}]\), all the data during the cavitation growth for various CNP and dNP fall into a master curve, which is simply characterized by a power-law scaling \((\tilde{R}\propto {\tilde{t}}^{\alpha })\) with an exponent α = 1/3 over two orders of magnitude of \(\tilde{t}\) (Fig. 1f). This scaling law likely implies a constant growth rate of cavitation volume (dV/dt = constant) as in the production limit24.

Phase diagram of cavitation

Now we proceed to establish the phase diagram of cavitation by impacting lasers on water samples within a broad range of CNP up to ten orders of magnitude (10−12 to 10−2) and various dNP (100, 200, 500 nm and 1 μm) (Fig. 2). All the data are categorized into three groups: no cavitation (yellow circles) at lower concentration, cavitation (red triangles) at medium concentration, and pseudo-cavitation (blue squares) at higher concentrations.

Phase diagram of cavitation dependent on dNP and CNP. Three regimes of no cavitation, cavitation, and pseudo-cavitation are separated by two boundary lines. One is the red line plotted from Eq. (1) to show a threshold for cavitation formation at lower CNP, while the other is the blue line to indicate the threshold for pseudo-cavitation at higher CNP.

These three groups are separated by two boundary lines: one is a low-concentration boundary for the transition from no cavitation to cavitation (the red line), while the other line is a high-concentration boundary for the transition from cavitation to pseudo-cavitation (the blue line). For the lower-concentration boundary, to overcome the interfacial energy to produce cavitation, at least a seeding NP is required to serve as pre-existing nucleus in water which is heated by the laser due to the strong absorption. Approximately, the volume of this heated water is \({V}_{heated}\sim {R}_{0}^{2}h\) (h for the penetration depth of CO2 laser in water). Then based on this simplified argument, the lower-concentration boundary is given by

\({C}_{NP}^{low}\sim {d}_{NP}^{3}\) implies that the required CNP for cavitation formation increases with dNP with a power-law scaling of 3 (the red line), which is consistent with the observation. Once CNP is above the low-concentration boundary, cavitation is formed.

However, as CNP is further increased to be much higher, the pseudo-cavitation occurs and the corresponding high-concentration boundary is nearly independent of concentration, as indicated by the blue line. The exact mechanism of this transition is not fully understood, but possibly more NPs are likely aggregated at the cavitation interface to affect cavitation growth. In the limit that the cavitation surface is fully covered by NPs (similar to the Pickering emulsion stabilized by particles29 or the formed shell by particle accumulation in a Leidenfrost droplet30), the development or growth of cavitation can be prevented and only surface indentation occurs, leading to the transition from cavitation to pseudo-cavitation.

Temperature visualization

Visualization of interfacial temperature

Unlike the bulk cavitation immersed inside water31,32,33, interfacial cavitation is exposed to the ambient air, so the spatiotemporal evolution of interfacial temperature can be directly visualized using a thermal camera (FLIR A 6750sc, Fig. 3a and SV 2), revealing the correlation between cavitation and temperature. For the typical case of no cavitation, cavitation and pseudo-cavitation corresponding to CNP = 10−9, 10−4 and 10−3, the thermal snapshots and temperature profiles are compared in Fig. 3b,c, after 3 seconds upon laser impacting on water (dNP = 500 nm, Plaser = 35 W). The peak temperature (Tpeak), the highest temperature from the temperature profile of Fig. 3c is ~150 °C for no cavitation at CNP = 10−9, then increases to ~108 °C at CNP = 10−4, but drops down to ~130 °C at CNP = 10−3.

Visualization of interfacial temperature. (a) An overview for laser impacting on water, and the white rectangular indicating the air/water interface. (b,c) For three CNP at 10−9, 10−4 and 10−3, the typical thermal images (b) and the temperature distribution dependent on the radial position (Rpos) along a horizontal line through the center (c) at t = 3 sec (t = 0 sec refers to the moment of laser shotting on water surface). (d,e) At CNP = 10−4 for cavitation, the typical thermal images (d) and the temperature distribution (e) before (t = 3 sec) and after (t = 3.033 sec) cavitation occurs. (f,g) At CNP = 10−3 for pseudo-cavitation, the typical thermal images (f) and the temperature distribution (g) before (t = 4.533 sec) and after (t = 4.566 sec) pseudo-cavitation occurs. The thermal camera is operated at 30 Hz with the recorded temperature range from 80~200 °C. (dNP = 500 nm, Plaser = 35 W).

Additionally, the temperature profiles are presented before the cavitation formation and right after the cavitation formation. At CNP = 10−4 for cavitation (Fig. 3d,e), the water is in a superheated state and Tpeak reaches as high as ~180 °C at t = 3 sec. Then after 33 ms (at t = 3.033 sec), the cavitation is generated, and temperature decreases in the center while off-center satellite peaks (Toff) occur locally away from the center. But at higher CNP = 10−3 for pseudo-cavitation (Fig. 3f,g), Tpeak is ~140 °C. After 33 ms, the pseudo-cavitation is generated with many local off-center satellite temperature peaks, as shown in Fig. 3g.

The radial symmetry of the temperature profile is preserved for no cavitation at the lower CNP = 10−9, but is broken with the appearance of off-center Toff at a higher concentration for either cavitation or pseudo-cavitation (Fig. 3 and SV 2). The off-center Toff might be caused by the strong convection to push the central region of heated liquid outward radically associated with cavitation or pseudo-cavitation. Indeed this dominant convection is correspondingly correlated with a large Péclet Number, \(Pe=Lu/\alpha \sim {10}^{3}\gg 1\) 34, where α ~ 0.6 w/(m · k) is thermal diffusivity of water, l ~ mm is the characterized length scale, and u ~ m/s is typical flow velocity.

Surface temperature dependent on C NP

Here, the evolution of Tpeak is presented at CNP = 10−9, 10−4 and 10−3 (Fig. 4a). At a lower CNP = 10−9 for no cavitation, the water temperature is elevated arising from the strong absorption of laser energy by water, and Tpeak is relatively stable around 150 °C. However, at a higher CNP = 10−4 for cavitation, the surface temperature presents strong fluctuations and can reach as high as 180 °C, which is clearly larger than the temperatures recorded for CNP = 10−9. Besides the water absorption, polymer NPs here might also be heated up by the laser, and this additional absorbed energy is localized due to the small thermal conductivity of polymer NPs, resulting in an further increased temperature. From the classical nucleation theory for cavitation formation which is strongly dependent on temperature, the nucleation rate grows by orders of magnitude when the water temperature is increased by 30 °C. But at a much higher CNP = 10−3 for the pseudo-cavitation, the recorded temperature drops down to ~100 °C with much weaker fluctuations. Rayleigh scattering from NPs (d/λ ≈ 1/20) might play a key role to cause the dramatic reduction of light absorption by water, leading to the sudden drop of the measured temperature. The plasmonic effect associated with metal NPs, by which the liquid temperature is increased with NPs concentration, should be irrelevant here for polymer NPs.

Temperature dependent on NPs. (a) The evolution of peak temperature (Tpeak) for dNP = 500 nm with CNP at 10−9, 10−4 and 10−3. (b) Time-averaged peak temperature \(({\bar{T}}_{peak})\) is related with both CNP and dNP, resulting in no cavitation (green symbols), cavitation (red symbols) and pseudo-cavitation (blue symbols). (Plaser = 35 W).

Correlation among cavitation, temperature and NPs

The whole process of cavitation at CNP = 10−4 with strong fluctuations of Tpeak (the red line) can be comprehended as follows: Initially, water is superheated through strong absorption upon the arrival of laser. Then, cavitation is produced by the heterogeneous nucleation at the elevated temperature. Subsequently, an explosion is followed by creating a plume and splashing of tiny droplets (Fig. 1c), which may temporarily reduce the laser intensity at the water interface and also expose colder water. Eventually, the temperature of the liquid is reduced and the next cycle of heating begins. Consequently, the growth and collapse of the cavitation leads to the strong fluctuations of temperature.

Cavitation associated with NPs and temperature is identified (Fig. 4b) for various dNP with a broad range of cNP [no cavitation (green symbols), cavitation (red symbols), and pseudo-cavitation (blue symbols)]. \({\bar{T}}_{peak}\) (the time-averaged Tpeak) for no cavitation and cavitation is similar, which is attributed to the photothermal effect of water with strong absorption at the infrared wavelength. However, cavitation (red symbols) is characterized by strong fluctuations (larger error bar), as the heating and cooling process is associated with cavitation. At a much higher CNP = 10−3 for pseudo-cavitation, \({\bar{T}}_{peak}\) drops dramatically, which might be due to Rayleigh scattering from NPs. Hence, polymer NPs not only act as preexisted nuclei to promote nucleation for cavitation, but also likely affect temperature to change the nucleation rate.

Application to fabrication of core-shell cavitation

Cavitation at the air/hexane interface

Besides water, cavitation also can be generated by lasers impacting on other liquids. For example, we studied a CO2 laser impacting on hexane (Table 1), and high-speed imaging shows the cavitation dynamics (Fig. 5a,b). During the growth stage (Fig. 5c), a power-law scaling \((\tilde{R}\propto {\tilde{t}}^{\alpha })\) with an exponent α = 1/3 still holds in the production limit24.

Core-shell cavitation at the water/hexane interface

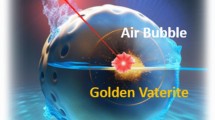

Here, by decorating a thin layer of hexane on top of water (Fig. 6a,b), we further demonstrate a core-shell cavitation by impacting a CO2 laser on this compound fluid interface. The thickness of top liquid hexane is designed to be on the order of the penetration depth, around 1 mm (an absorption peak of 8 cm−1 at 10.6 μm, Table 1), so that the laser remains strong enough to impact on the compound water/hexane interface, likely resulting in an interesting cavitation.

For distilled water without NPs (Fig. 6a), cavitation is observed in the upper layer of hexane with dye (see Methods), while no cavitation is formed in water. In contrast, for water with seeding NPs (dNP = 500 nm and CNP = 10−5) (Fig. 6b), interestingly a core-shell cavitation is obtained. Further, this core-shell cavitation is observed at various dNP and CNP. The gas component inside the inner core might be composed of hexane vapor, water vapor, or their mixture, which is produced at the elevated temperature and encapsulated by the hexane. This core-shell cavitation demonstrates the controllable capability to fabricate novel cavitations by designing the compound interface.

Discussion and Outlook

For bulk cavitation inside water, the pressure in the cavitation can be estimated by an isothermal or adiabatical approximation, and the associated dynamics can be described by a Rayleigh-Plesset equation. Here the produced cavitation at the air/water interface is exposed to the ambient air and the atmospheric pressure, and the strong photothermal process during the laser impact on water leads to a complicated heat transfer and temperature distribution. Hence, an accurate calculation of the pressure and temperature might be challenging theoretically to quantitatively characterize the dynamical process including both expansion and collapse for the system here.

By taking advantage of NPs and strong absorption of water, the laser intensity for thermal cavitation is reduced by 2 orders of magnitude (down to 102 W/cm2), making possible the operation at a lower laser intensity. Typically, during a laser pulse (down to nanoseconds or picoseconds) impacting on liquids, an extremely high laser intensity (up to ~1011 W/cm2)35 triggers a rapid and complicated response from the liquid at an initial stage, resulting in plasma formation and shock waves12,36. But here the continuous laser with intensity down to 102 W/cm2 is much lower than the optical breakdown threshold, and shock is less obvious and can be negligible. The lower laser intensity also results in a much lower temperature of cavitation (in the range of 110~160 °C), compared to the elevated temperature of cavitation (up to thousand degrees) in conventional optical breakdown37,38.

Additionally, more future work is required to thoroughly understand the complicated \({\bar{T}}_{peak}\) dependence on NP parameters such as dNP and CNP. Yet from the experimental point of view, despite the limited frame rates of the thermal camera constraining the capability to capture the highest temperature during the fast process of cavitation, the direct visualization of the spatiotemporal evolution of temperature has evidently revealed the inherent correlation between the temperature, NPs and cavitation.

A compound interface39 might be designed with various liquids to attain more sophisticated structured cavitation with promising functionalities, such as the separation and selection of liquid phases, or the delivery of targeted liquid. Although complicated liquid structures can be generated by other approaches such as a microcapillary device40, the structured cavitation here might be particularly applicable for laser-related technological applications, such as CO2-laser surgery14,15, and the precise manipulation of microstructures in materials science41. Moreover, the novel core-shell cavitation together with the recently reported conical interfaces42 might inspire more future studies on the compound interface of two immiscible fluids impacted by a laser beam and the subsequent diverse patterns and structures.

Conclusion

In summary, by taking advantage of seeding NPs and a strong photothermal effect, we report a CO2 laser impacting on water to produce interfacial cavitation, allowing the direct visualization of the spatiotemporal evolution of temperature to reveal the underlying correlation among cavitation, nanoparticles and temperature. By systematically investigating a broad range of NPs concentration and size, a phase diagram is established with three identified regimes (no cavitation, cavitation, and pseudo-cavitation). These findings indicate that NPs not only act as preexisted nuclei to promote nucleation for cavitation, but also likely affect temperature to change the nucleation rate as well. Moreover, by exploiting a hexane/water interface, a core-shell cavitation is demonstrated. This work offers more opportunities to attain and control cavitations by choosing NPs and designing the compound interface, while operating at a lower laser intensity, for versatile technological applications in material science and medical surgery.

Methods

Experimental setup

A schematic diagram depicting the experimental setup is shown in Fig. 7. A continuous-wave CO2 laser (Access laser, AL30D, the power Plaser = 35 W, the diameter of Gaussian beam D0 = 2R0 = 3 mm) with wavelength of 10.6 μm is impacted on water in a glass cuvette (10 mm × 10 mm × 5 mm). The output laser beam is reflected by a lens and then irradiated downward into the glass cuvette. The collimated laser beam diameter is 3 mm, and the output laser power is 35 W. Cavitation is visualized using bright-field photography by a high-speed camera (Phantom V611 from Vision Research, up to 106 frames per second) or a colored high-speed camera (Phantom C110), coupled with a macro lens (Tokina 100 mm F2.8d). A xenon lamp with a maximum power of 350 W used as an auxiliary lighting source is put on the other side of the cuvette, to project the cavitation’s shadow on the Phantom fast camera for better imaging effect. A thermal camera (FLIR A 6750sc) is adopted to acquire the temperature distribution on the water surface during the cavitation process.

For the seeding polymer NPs (ThermoFisher Scientific, polystyrene with an absorption peak about 170 cm−1 at the wavelength of 10.6 μm43), the volume concentration (the ratio between the total NPs volume and the water volume) such as CNP = 6 × 10−3, is obtained by diluting 1 ml polystyrene NPs (10−2 g/ml) with the distilled water (Shanghai Dienabiotech) into 10 ml solution in the volumetric flask. By the similar procedure, the various concentrations are obtained.

For the dye of hexane, since both water and hexane are transparent liquids, the hexane was saturated with the organosulfur (tetrathiafulvalene) into the orange color, and the compound interface is better visualized by a colored fast-speed camera (Phantom C110, SV 3).

References

Rayleigh, L. On the pressure developed in a liquid during the collapse of a spherical cavity. Philos. Mag. Ser. 6, 94–98, https://doi.org/10.1080/14786440808635681 (1917).

Gimenez, G. & Goby, F. Effect of polarization on electric pulses produced by cavitation bubbles. In Cavitation and Inhomogeneities in Underwater Acoustics, 101–107, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-51070-0_15 (Springer, 1980).

Arndt, R. E. Cavitation in fluid machinery and hydraulic structures. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 13, 273–326, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.fl.13.010181.001421 (1981).

Prosperetti, A. Vapor bubbles. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mchanics 49, 221–248, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-010816-060221 (2017).

Delville, J.-P. et al. Laser microfluidics: fluid actuation by light. J. Opt. A: Pure Appl. Opt. 11, 034015, https://doi.org/10.1088/1464-4258/11/3/034015 (2009).

Kim, D. & Lee, J. On the physical mechanisms of liquid-assisted laser cleaning. J. Appl. Phys. 93, 762–764, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1527207 (2003).

Ohl, C.-D., Arora, M., Dijkink, R., Janve, V. & Lohse, D. Surface cleaning from laser-induced cavitation bubbles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 074102, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2337506 (2006).

Yang, G. Laser ablation in liquids: Applications in the synthesis of nanocrystals. Prog. Mater. Sci. 52, 648–698, https://doi.org/10.1002/chin.200738227 (2007).

Zhang, D., Gokce, B. & Barcikowski, S. Laser synthesis and processing of colloids: fundamentals and applications. Chem. Rev. 117, 3990–4103, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00468 (2017).

Sajjadi, A. Y., Mitra, K. & Grace, M. Ablation of subsurface tumors using an ultra-short pulse laser. Opt. Lasers Eng. 49, 451–456, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlaseng.2010.11.020 (2011).

Kafalas, P. & Ferdinand, A. Fog droplet vaporization and fragmentation by a 10.6-μm laser pulse. Appl. Opt. 12, 29–33, https://doi.org/10.1364/ao.12.000772 (1973).

Klein, A. L. et al. Drop shaping by laser-pulse impact. Phys. Rev. Appl. 3, 044018, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.3.044018 (2015).

Vogel, A. & Venugopalan, V. Mechanisms of pulsed laser ablation of biological tissues. Chem. Rev. 103, 577–644, https://doi.org/10.1002/chin.200318293 (2003).

Ascher, P. W. & Heppner, F. CO2-laser in neurosurgery. Neurosurg. Rev. 7, 123–133, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01780695 (1984).

Straus, D., Moftakhar, R., Fink, Y., Patel, D. & Byrne, R. W. Application of novel CO2 laser-suction device. J. Neurol. Surg. Part B: Skull Base 74, 358–363, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1347373 (2013).

Amininik, S. et al. Ultrafast mid-IR laser scalpel: Protein signals of the fundamental limits to minimally invasive surgery. PLoS One 5, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013053 (2010).

Kennedy, P. K., Hammer, D. X. & Rockwell, B. A. Laser-induced breakdown in aqueous media. Prog. Quantum Electron. 21, 155–248, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6727(97)00002-5 (1997).

Padilla-Martinez, J., Berrospe-Rodriguez, C., Aguilar, G., Ramirez-San-Juan, J. & Ramos-Garcia, R. Optic cavitation with CW lasers: A review. Phys. Fluids 26, 122007, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4904718 (2014).

Zwaan, E., Le Gac, S., Tsuji, K. & Ohl, C.-D. Controlled cavitation in microfluidic systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 254501, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.98.254501 (2007).

Caupin, F. & Herbert, E. Cavitation in water: a review. Comptes Rendus Physique 7, 1000–1017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crhy.2006.10.015 (2006).

Li, B., Gu, Y. & Chen, M. Cavitation inception of water with solid nanoparticles: A molecular dynamics study. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 51, 120–128, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.10.036 (2019).

Fang, Z. et al. Evolution of light-induced vapor generation at a liquid-immersed metallic nanoparticle. Nano Lett. 13, 1736–1742, https://doi.org/10.1021/nl4003238 (2013).

Neumann, O. et al. Solar vapor generation enabled by nanoparticles. ACS Nano 7, 42–49, https://doi.org/10.1021/nn304948h (2012).

Wang, Y. et al. Vapor and gas-bubble growth dynamics around laser-irradiated, water-immersed plasmonic nanoparticles. ACS Nano 11, 2045–2051, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.6b08229 (2017).

Zhou, L. et al. 3D self-assembly of aluminium nanoparticles for plasmon-enhanced solar desalination. Nat. Photonics 10, 393, https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2016.75 (2016).

Robertson, C. W. & Williams, D. Lambert absorption coefficients of water in the infrared. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 61, 1316–1320, https://doi.org/10.1364/josa.61.001316 (1971).

Jansen, E. D., van Leeuwen, T. G., Motamedi, M., Borst, C. & Welch, A. J. Partial vaporization model for pulsed mid-infrared laser ablation of water. J. Appl. Phys. 78, 564–571, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.360642 (1995).

Park, H. K., Kim, D., Grigoropoulos, C. P. & Tam, A. C. Pressure generation and measurement in the rapid vaporization of water on a pulsed-laser-heated surface. J. Appl. Phys. 80, 4072–4081, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.363370 (1996).

Aveyard, R., Binks, B. P. & Clint, J. H. Emulsions stabilised solely by colloidal particles. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 100, 503–546, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0001-8686(02)00069-6 (2003).

Lyu, S. et al. Final fate of a leidenfrost droplet: Explosion or takeoff. Sci. Adv. 5, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aav8081 (2019).

Flint, E. B. & Suslick, K. S. The temperature of cavitation. Science 253, 1397–1399, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.253.5026.1397 (1991).

Cordero, M. L., Verneuil, E., Gallaire, F. & Baroud, C. N. Time-resolved temperature rise in a thin liquid film due to laser absorption. Phys. Rev. E 79, 011201, https://doi.org/10.1103/physreve.79.011201 (2009).

Quinto-Su, P. A., Suzuki, M. & Ohl, C.-D. Fast temperature measurement following single laser-induced cavitation inside a microfluidic gap. Sci. Reports 4, 5445, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05445 (2015).

Venugopalan, V., Nishioka, N. & Mikic, B. The effect of laser parameters on the zone of thermal injury produced by laser ablation of biological tissue. J. Biomech. Eng. 116, 62–70, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2895706 (1994).

Zysset, B., Fujimoto, J. G. & Deutsch, T. F. Time-resolved measurements of picosecond optical breakdown. Appl. Phys. B 48, 139–147, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00692139 (1989).

Vogel, A., Busch, S. & Parlitz, U. Shock wave emission and cavitation bubble generation by picosecond and nanosecond optical breakdown in water. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 100, 148–165, https://doi.org/10.1121/1.415878 (1996).

Akhatov, I. et al. Collapse and rebound of a laser-induced cavitation bubble. Phys. Fluids 13, 2805–2819, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1401810 (2001).

Byun, K.-T., Kwak, H.-Y. & Karng, S. W. Bubble evolution and radiation mechanism for laser-induced collapsing bubble in water. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 43, 6364, https://doi.org/10.1143/jjap.43.6364 (2004).

Atencia, J. & Beebe, D. J. Controlled microfluidic interfaces. Nature 437, 648, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04163 (2004).

Utada, A. et al. Monodisperse double emulsions generated from a microcapillary device. Science 308, 537–541, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1109164 (2005).

Quinto-Su, P., Huang, X., Gonzalez-Avila, S., Wu, T. & Ohl, C. Manipulation and microrheology of carbon nanotubes with laser-induced cavitation bubbles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 014501, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.104.014501 (2010).

Girot, A. et al. Conical interfaces between two immiscible fluids induced by an optical laser beam. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 174501, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.122.174501 (2019).

Thompson, H. W. & Torkington, P. The infra-red spectra of polymers and related monomers. Proc. Royal Soc. London. Ser. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 184, 3–20, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1943.0036 (1945).

Acknowledgements

This research has been financially supported by the National Young Thousand Talents Plan of China (Nos KHH2126001, QXH2126001, QXH2126002), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11704077), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2018T110342), and startup from Fudan University (Nos JIH2126102, JIH2126023), and the Materials Research Science and Engineering Center Program of the National Science Foundation under Award DMR-1419807. Deng acknowledges Dr. Burak Temelkuran and Dr. Mihai Ibanescuat Omniguide in USA for the initial experiments, Prof. John Bush at MIT for initial discussions, Prof. Shmuel M. Rubinstein in Harvard University for stimulating discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H. built the experimental apparatus, performed the experiments; M.H. and F.W. analyzed the data. P.H. prepared the water samples; X.P., S.J. and Y.F. discussed the results. M.H., F.W. and D.D. wrote the manuscript, and D.D. supervised the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, M., Wang, F., Huo, P. et al. Nanoparticle-Mediated Cavitation via CO2 Laser Impacting on Water: Concentration Effect, Temperature Visualization, and Core-Shell Structures. Sci Rep 9, 18326 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54531-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54531-1

This article is cited by

-

Near-infrared-laser-navigated dancing bubble within water via a thermally conductive interface

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.