Abstract

We aimed to reveal clinicopathological features and explore survival-related factors of colorectal signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC). A population-based study was carried out to investigate colorectal SRCC by using data extracted from the surveillance, epidemiology and end results (SEER) database between 2004 and 2015. In total, 3,278 patients with colorectal SRCC were identified, with a median age of 63 (12–103) years old. The lesions of most patients (60.49%) were located in the cecum–transverse colon. In addition, 81.27% patients had advanced clinical stage (stage III/IV), and 76.69% patients had high pathological grade. The 3–, 5–year cancer‐specific survival and overall survival rate was 35.76%, 29.32% and 32.32%, 25.14%. Multivariate analysis revealed that primary site in cecum–transverse colon, married, received surgery, lymph node dissections ≥ 4 regional lymph nodes were independent favorable prognostic. Meanwhile, aged ≥ 65 years, higher grade, tumor size ˃5 cm and advanced AJCC stage were associated with poor prognosis. Patient age, tumor grade, marital status, tumor size, primary tumor location, AJCC stage, surgery and number of dissected lymph node had significant correlation with prognosis of colorectal SRCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is still a main global health burden, ranking the second of all types of malignancies in terms of cancer-associated mortality1. Recently accumulative attention has been paid to colorectal signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC), initially proposed by Saphir and Laufman in 19512. Stomach is considered as the most common site for primary SRCC, while colorectal SRCC is less frequent3. In addition, colorectal SRCC is a very rare and special type of all CRCs, which has its unique clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis4,5,6,7,8.

Various researches have shown the origination of SRCC from undifferentiated stem cells of colorectal mucosa, thus, rapid growth, poor differentiation, diffuse infiltration as well as high metastatic rate are generally observed9,10. Moreover, SRCC has been considered as an independent prognostic indicator for poor outcome based on the AJCC stage system11. However, the currently limited understanding of colorectal SRCC is mainly based on case reports as well as small case series, without complete elucidation on the clinicopathological features and prognosis12.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH)’ s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database, the most authoritative and largest cancer dataset in North America13, covers nearly 30% of population in the USA from different geographic regions14, which provides valuable data to investigate rare malignancies15,16,17. Therefore, we performed a retrospective analysis of patients with colorectal SRCC registered in the SEER database to summarize clinical characteristics and survival and to delineate features influencing prognosis.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

In order to obtain relevant data from the database, we signed the SEER Research Data Agreement (No. 19817-Nov2018) and further searched for data according to the approved guidelines. The extracted data were publicly available and de-identified, and the data analysis was considered as non-human subjects by Office for Human Research Protection, therefore, no approval was required from institutional review board.

Study population

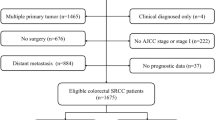

SEER*State v8.3.6 tool was used to select qualified subjects. Colorectal SRCC patients who were diagnosed from January 1, 2004 to December 31, 2015 were selected from the Incidence-SEER 18 Registries Custom Data (with additional treatment fields), released August 2019, based on the November 2018 submission. The inclusion criteria included the following: (1) it should be primary colorectal SRCC patients; (2) SRCC diagnosed in line with the International Classification of Disease for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3; coded as 8,490/3). The exclusion criteria were listed in the following: (1) Patients had multiple primary tumors; (2) Patients with reported diagnosis source from autopsy or death certificate or only clinically diagnosed; (3) Patients did not have some important clinicopathological information, including: AJCC stage and surgical style; (4) Patients had no prognostic data. The remaining qualified populations were included.

Covariates and endpoint

We analyzed the patients’ characteristics according to the following factors: year of diagnosis (2004–2007, 2008–2011, 2012–2015); insured status (uninsured/unknown, any medicaid/insured; age(< 65, ≥ 65); marital status (unmarried, married); gender (female, male); race (black, white or others); primary site(cecum–transverse colon, descending colon–sigmoid, multiple, rectum and unknown); grade (grade I/II, grade III/IV, unknown); tumor size (≤ 5 cm, ˃5 cm,unknown); AJCC stage ( stage I, II, III, IV); surgery(no surgery, local tumor excision /partial colectomy, total colectomy), and lymph node dissection (none or biopsy, 1 to 3 regional lymph nodes removed, ≥ 4 regional lymph nodes removed, unknown).The widowed or single (never married or having a domestic partner) or divorced or separated patients were classified as unmarried. The primary tumor site was classified as cecum–transverse colon (including the cecum, appendix, ascending colon, hepatic flexure and the transverse colon), descending colon–sigmoid (including the splenic flexure and descending and sigmoid colons), multiple, rectum and unknown18. Year of diagnosis was equally divided into 2004–2007, 2008–2011, 2012–2015, which was referred to the previous papers19,20. The grouping of the age21 and tumor size22 also refers to the published studies. In addition, the staging of cancer is based on the 6th edition of AJCC stage system, which adapted to patients in the SEER database with a diagnosis time of 2004–201523.

The endpoint of this study was cancer‐specific survival (CSS) and overall survival (OS). CSS was defined as the period from diagnosis to death attributed to colorectal SRCC. OS was defined as the period from diagnosis to death from any cause.

Statistical analysis

Kaplan–Meier (K–M) method was employed for univariate analysis and stratified analysis, followed by log-rank test to determine the differences of OS and CSS. Of note, if variables had P values ≤ 0.1 in univariate analysis, they were incorporated into multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis. SPSS software version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) was adopted for statistical analysis, and GraphPad Prism 5 was adopted for plotting survival curves. A two-sided P < 0.05 was suggestive of statistical significance.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 3,278 eligible subjects were included. The flowchart of patient selection was displayed in Fig. 1.The patients’ features and therapeutic regimens were listed in Table 1. Of all the included patients, the median age was 63 (12–103) years old, with the male to female ratio of nearly 1:1.The lesions were mostly located in cecum–transverse colon (60.49%), 640 cases (19.52%) were detected in rectum, 515 cases (15.71%) were observed in descending colon–sigmoid and only 50 cases (1.53%) were located in overlapping of colon. Most of colorectal SRCC were in advanced clinical stage (stage III/IV: 81.27%) and high pathological grade (grade III/IV: 76.69%). Surgical resection was performed on 2,602 (79.38%) patients, including 1738 (53.02%) patients received total colectomy. Most patients (70.41%) had ≥ 4 regional lymph nodes removed.

Patient survival

The median survival time of all included patients was 16.0 months (0–155 months). The 1–, 3– and 5–year CSS rate was 62.66%, 35.76%, and 29.32%, respectively (Fig. 2A). Meanwhile, the 1–, 3–and 5–year OS rate was 59.57%, 32.32% and 25.14%, respectively (Fig. 2B). K-M curves based on AJCC stage was displayed in Fig. 3A (CSS) and Fig. 3B (OS). Significantly poorer prognosis was detected in subjects with stages III or IV compared to those with stages I or II (both P < 0.0001). The 5–year CSS and OS rate in subjects with stage I were 73.66% and 65.63%; stage II: 69.81% and 57.72%; stage III: 37.31% and 31.94%; stage IV: 4.80% and 4.24%, indicating inferior outcome in those with stages III or IV.

Prognostic factors of survival and stratified analysis

In the univariate analyses, marital status, primary tumor location, tumor size, AJCC stage, grade, surgery and dissected lymph node were predictors of CSS (all P < 0.05). Additionally, multivariate analysis further demonstrated that married status (HR 0.863, 95% CI 0.792–0.940, P = 0.001); primary site in cecum–transverse colon (P = 0.001) and surgery [(local tumor excision/partial colectomy) HR 0.609, 95% CI 0.506–0.734; (total colectomy) HR 0.693, 95% CI 0.571–0.840, both P < 0.001] were independent prognostic indicators for better survival. Meanwhile, higher grade (HR 1.679, 95% CI 1.347–2.094, P < 0.001), tumor size ˃5 cm (HR 1.297, 95% CI 1.170–1.438, P < 0.001) and advanced AJCC stage [(stage III) HR 3.353, 95% CI 2.401–4.682; (stage IV) HR 7.723, 95% CI 5.539–10.769, both P < 0.001] could independently predict worse prognosis. Similar outcomes were observed in multivariate analysis on OS. Besides, it found that aged ≥ 65 years (HR 1.712, 95% CI 1.574–1.863, P < 0.001) and lymph node dissection ≥ 4 (HR 0.777, 95% CI 0.659–0.917, P = 0.003) were also independent prognostic indicators of OS (Table 2).

Discussion

According to the WHO definition, colorectal SRCC is a special type of CRC with prominent intracytoplasmic mucin in over 50% of tumor cells24, featured by unique clinical manifestation as well as distinct outcome. Colorectal SRCC has been validated to have poorer prognosis compared with other common CRC4. Colorectal SRCC, a rare subtype of CRC, consists of 0.1% to 2.6% of all CRC cases25,26. Previous research found similar incidence of SRCC between female and male6,27 and most SRCC cases are located in the right colon, with rectal SRCC of approximately 20%28. Additionally, the initial diagnosis of SRCC is generally at advanced stage, compared with colorectal non-SRCC4. For instance, according to a large cohort study in the USA, 80% of colorectal SRCC were initially diagnosed with stage III and IV, which were only 50% in non-SRCC (P < 0.01)28. These findings are consistent with our study. Moreover, we found that the median age was 63 years old in patients with colorectal SRCC, and 1537 (46.89%) patients were old patients. Our results should be more reliable in this large population-based study while most previous researches on colorectal SRCC were only based on single institution.

Colorectal SRCC is independently related to increased mortality risks18,20. Ramya et al. have revealed that the median OS was 18.6 months by involving 206 subjects with colonic SRCC7. In addition, the stage-specific 5-year survival rate was declined with advanced stage. The above results are basically consistent with our results, while the median survival time of our study is shorter (16.0 months).

Multiple studies have evaluated the stage-associated in colorectal SRCC, with consistent outcomes indicating better survival in early-stage SRCC7. Tumor location may be another independent prognostic indicator29. These two prognostic factors are both found in our study. In addition, we found that pathological grade and tumor size were independent prognostic factors of colorectal SRCC.

In terms of the optimal therapeutic regimens, the multidisciplinary management is required for colorectal SRCC. To be specific, surgical intervention is vitally involved in treating localized tumors12. Additionally, a large population-based study has evaluated the significance of adjuvant chemotherapy by extracting relevant data from nationwide population-based Netherlands Cancer Registry, which enrolled 1972 subjects with colorectal SRCC from 1989 to 2010. In this study, better survival outcome was detected in stage III colon SRCC patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy than those without6. Tao Shi et al. also found an association between chemotherapy and better survival outcomes in colorectal SRCC patients suffering from distant metastasis21. In contrast, the role of radiotherapy in colorectal SRCC is less studied which has not been evaluated alone or combined with chemotherapy in SRCC histology to date. Nevertheless, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy could give rise to good therapeutic response in rectal SRCC population30. This study further emphasized the importance of operation in colorectal SRCC, including the number of dissected lymph node, and regional lymph node dissection ≥ 4 significantly improved the prognosis of patients.

To our knowledge, the current research is the largest population-based study to explore prognostic indicators in colorectal SRCC in the past decade. In total, 3,278 colorectal SRCC patients were analyzed after retrieving from SEER database. SEER database renders the assessment of a large cross-section of cancer patients and provides long-term follow-up information without inherent institutional biases. Meanwhile, there are certain limitations in our research. Firstly, as a retrospective research based on SEER database, the intrinsic selection biases exists in this study15,17. Furthermore, not all data are available from the SEER database, such as molecular-genetic profiles. Thirdly, as the radiotherapy and chemotherapy variables have a relatively low sensitivity, we didn't include the data of radiotherapy and chemotherapy to avoid reporting misleading results. Finally, we could not determine the therapeutic response or recurrence rate according to the data extracted from SEER. Thus, further investigations are warranted in the future.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we analyzed clinicopathological features as well as survival of colorectal SRCC patients using a population-based approach. Consequently, patient age, tumor grade, marital status, tumor size, primary tumor location, AJCC stage, surgery and dissected lymph node had significant correlation with prognosis of colorectal SRCC. Our study is the largest population-based research to investigate clinicopathological features and survival of patients with colorectal SRCC. Hopefully, our findings are of great significance for the management and future prospective studies for colorectal SRCC.

References

M Arnold 2020 Global Burden of 5 Major Types Of Gastrointestinal Cancer Gastroenterology https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.068

H Laufman O Saphir 1951 Primary linitis plastica type of carcinoma of the colon A.M.A. Arch. Surg. 62 79 91 https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1951.01250030082009

UA Almagro 1983 Primary signet-ring carcinoma of the colon Cancer 52 1453 1457 https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19831015)52:8<1453::aid-cncr2820520819>3.0.co;2-9

U Nitsche 2013 Mucinous and signet-ring cell colorectal cancers differ from classical adenocarcinomas in tumor biology and prognosis Ann. Surg. 258 775 782 https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a69f7e

T Mizushima 2010 Primary colorectal signet-ring cell carcinoma: clinicopathological features and postoperative survival Surg. Today 40 234 238 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-009-4057-y

N Hugen 2015 Colorectal signet-ring cell carcinoma: benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy but a poor prognostic factor Int. J. Cancer 136 333 339 https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28981

R Thota X Fang S Subbiah 2014 Clinicopathological features and survival outcomes of primary signet ring cell and mucinous adenocarcinoma of colon: retrospective analysis of VACCR database J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 5 18 24 https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2013.051

PL Chalya 2013 Clinicopathological patterns and challenges of management of colorectal cancer in a resource-limited setting: a Tanzanian experience World J. Surg. Oncol. 11 88 https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-11-88

V Gopalan RA Smith YH Ho AK Lam 2011 Signet-ring cell carcinoma of colorectum–current perspectives and molecular biology Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 26 127 133 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-010-1037-z

N Hugen CJ Velde van de JH Wilt de ID Nagtegaal 2014 Metastatic pattern in colorectal cancer is strongly influenced by histological subtype Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 25 651 657 https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt591

SB Edge CC Compton 2010 The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM Ann. Surg. Oncol. 17 1471 1474 https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4

S Arifi O Elmesbahi A Amarti Riffi 2015 Primary signet ring cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum Bull. du Cancer 102 880 888 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bulcan.2015.07.005

JB Yu CP Gross LD Wilson BD Smith 2009 NCI SEER public-use data: applications and limitations in oncology research Oncol. (Williston Park, N.Y.) 23 288 295

KS Cahill EB Claus 2011 Treatment and survival of patients with nonmalignant intracranial meningioma: results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program of the National Cancer Institute. Clinical article J. Neurosurg. 115 259 267 https://doi.org/10.3171/2011.3.jns101748

RW Dudley 2015 Pediatric choroid plexus tumors: epidemiology, treatments, and outcome analysis on 202 children from the SEER database J. Neurooncol. 121 201 207 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-014-1628-6

RW Dudley 2015 Pediatric low-grade ganglioglioma: epidemiology, treatments, and outcome analysis on 348 children from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database Neurosurgery 76 313 319 https://doi.org/10.1227/neu.0000000000000619

TC Hankinson 2016 Short-term mortality following surgical procedures for the diagnosis of pediatric brain tumors: outcome analysis in 5533 children from SEER, 2004–2011 J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 17 289 297 https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.7.peds15224

U Nitsche 2016 Prognosis of mucinous and signet-ring cell colorectal cancer in a population-based cohort J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 142 2357 2366 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-016-2224-2

X Lv 2019 A nomogram for predicting bowel obstruction in preoperative colorectal cancer patients with clinical characteristics World J. Surg. Oncol. 17 21 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1562-3

SG Wu 2018 Survival in signet ring cell carcinoma varies based on primary tumor location: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database analysis Exp. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12 209 214 https://doi.org/10.1080/17474124.2018.1416291

T Shi 2019 Chemotherapy is associated with increased survival from colorectal signet ring cell carcinoma with distant metastasis: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database analysis Cancer Med. 8 1930 1940 https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.2054

F Wei H Lyu 2019 Postoperative radiotherapy improves survival in gastric signet-ring cell carcinoma: a SEER database analysis J. Gastric Cancer 19 393 407 https://doi.org/10.5230/jgc.2019.19.e36

M Shi B Zhou SP Yang 2020 Nomograms for predicting overall survival and cancer-specific survival in young patients with pancreatic cancer in the US based on the SEER database PeerJ 8 e8958 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8958

K Tajiri 2017 Clinicopathological and corresponding genetic features of colorectal signet ring cell carcinoma Anticancer Res. 37 3817 3823 https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.11760

S Belli 2014 Outcomes of surgical treatment of primary signet ring cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum: 22 cases reviewed with literature Int. Surg. 99 691 698 https://doi.org/10.9738/intsurg-d-14-00067.1

D Psathakis 1999 Ordinary colorectal adenocarcinoma vs. primary colorectal signet-ring cell carcinoma: study matched for age, gender, grade, and stage Dis. Colon Rectum. 42 1618 1625 https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02236218

SL Stewart JM Wike I Kato DR Lewis F Michaud 2006 A population-based study of colorectal cancer histology in the United States, 1998–2001 Cancer 107 1128 1141 https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22010

JR Hyngstrom 2012 Clinicopathology and outcomes for mucinous and signet ring colorectal adenocarcinoma: analysis from the national cancer data base Ann. Surg. Oncol. 19 2814 2821 https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-012-2321-7

S Ishihara 2012 Tumor location is a prognostic factor in poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, and signet-ring cell carcinoma of the colon Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 27 371 379 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-011-1343-0

SB Jayanand RA Seshadri R Tapkire 2011 Signet ring cell histology and non-circumferential tumors predict pathological complete response following neoadjuvant chemoradiation in rectal cancers Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 26 23 27 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-010-1082-7

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff members of the National Cancer Institute and their colleagues across the United States and at Information Management Services, Inc., who have been involved with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.H. conceived the study. L.Y. searched the database and literature. L.Y. and M.W. discussed and analyzed the data. L.Y. wrote the manuscript. P.H. revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Ll., Wang, M. & He, P. Clinicopathological characteristics and survival in colorectal signet ring cell carcinoma: a population-based study. Sci Rep 10, 10460 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67388-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67388-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.