Abstract

Vacancy-type defects in Mg-implanted GaN were probed by using a monoenergetic positron beam. Mg ions were implanted into GaN to obtain 0.3-μm-deep box profiles with Mg concentrations of 1 × 1019 cm−3. The major defect species in an as-implanted sample was determined to be Ga-vacancy related defects such as a complex between Ga and N vacancies. The sample was annealed under a nitrogen pressure of 1 GPa in a temperature range of 1000–1480 °C without a protective capping layer. Compared with the results for Mg-implanted GaN annealed with an AlN capping layer, the defect concentration was decreased by the cap-less annealing, suggesting that the surface of the sample was an effective sink for vacancies migrating toward the surface. Depth distributions of Mg after annealing above 1300 °C were influenced by the presence of residual vacancies at this temperature. Hydrogen atoms were unintentionally incorporated into the sample during annealing, and their diffusion properties were also affected by both vacancies and Mg.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gallium nitride (GaN) based power devices have attracted worldwide attention because of its excellent physical properties such as their wide bandgap, high saturation electron velocity, sufficient thermal conductivity, and high breakdown voltage1,2,3. Lateral power transistors and diodes based on AlGaN/GaN heterostructures are utilized widely in RF and power conversion applications. Due to their structures, however, the chip size tends to increase as the power rating increases, which often degrades device properties and reliability. In addition, the stability of the device performance is known to be affected by trapping and/or scattering centers of carriers at the AlGaN surface and/or near the dielectric/AlGaN interface. Vertical GaN power devices have attracted significant attention because the breakdown voltage can be increased as the thickness of the drift region increases without enlarging the chip size3,4. This structure also leads to superior reliability due to reduction in the high electric field from the surface.

These vertical power devices require embedded p-type regions to suppress the electric field spreading near the edges of junctions, which is effective for obtaining high breakdown voltages4. Ion implantation is a common technique for selective p-type doping. The effects of ion implantation into GaN have been widely studied, and it is well known that the removal of implantation induced defects is difficult compared with that for Si or SiC5,6. During annealing, implantation induced point defects can either recombine or interact to form various kinds of defects or extended defects such as stacking faults and dislocation loops. The annealing temperature of such defects was reported to higher than the decomposition temperature of GaN (about 850 °C, Ref.7). However, several reports of successful Mg activation have started to appear recently8,9,10,11,12,13. In order to suppress surface damages during high-temperature annealing, a protective capping layer is deposited on the surface of GaN. Here, the chemical stability of the interface between the capping layer and GaN is important. Jacobs et al.13 reported that surface degradation due to multicycle rapid thermal annealing depended on the selection of materials and/or the deposition process of the capping layer. Narita et al.10 reported p–n diode formation by Mg- and H-implantation, where the ions were implanted into GaN(000\(\stackrel{-}{1}\)) substrates. Since the (000\(\stackrel{-}{1}\)) face is thermally more stable than the (0001) face, the annealing (1230 °C) was performed without a capping layer. Recently, Sakurai et al.11 reported that a high activation rate for Mg (70%) can be obtained without a capping layer by using an ultra-high-pressure annealing (UHPA) process. In their experiments, annealing was done with an N2 pressure of 1 GPa, and the maximum temperature was 1480 °C.

The materials and deposition processes of the capping layer are designed to suppress interatomic diffusion between the capping layer and GaN during high-temperature annealing. But this property also suppresses the migration of vacancy-type defects toward the surface and results in vacancy clustering below the capping layer14. Although an annealing treatment without a capping layer is ideal, the behaviors of point defects during annealing are not known. It is known that nitrogen vacancy (VN) acts as a compensator15, but other defects, such as complexes between Mg and vacancies, are also candidates which decrease an activation rate of Mg. Since many kinds of defects are introduced by ion implantation and post-implantation annealing6, a study of annealing behaviors of defects, such as agglomeration of vacancies and their dissociation, is also important for effectively utilizing ion implantation for GaN devices. Positron annihilation is a useful technique for a study of vacancy-type defects in semiconductors16,17, and this technique has been successfully used to detect vacancy-type defects in GaN18,19,20,21. In the present study, we used a monoenergetic positron beam to study the annealing behaviors of vacancy-type defects in Mg-implanted GaN with UHPA.

Experiment

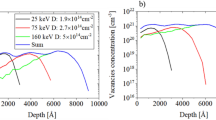

The present samples were undoped GaN films with 2-µm-thickness grown by using metal–organic vapor phase deposition (MOVPE). Details on the sample preparation process and the electric properties of the samples after UHPA are given elsewhere11,12. Before the deposition of the top GaN film, a 0.2-μm-thick buffer layer (n+-GaN) was grown on c+-GaN substrates obtained by hydride vapor phase epitaxy (HVPE). Carbon and oxygen concentrations in the GaN film were estimated by secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS), and they were lower than 4 × 1015 cm−3 and 3 × 1015 cm−3, respectively (detection limit). Mg+ ions were implanted into the samples to obtain 300-nm-deep box profiles with Mg concentrations [Mg] of 1 × 1019 cm−3 at room temperature. The energies of Mg ions were 30, 70, 150, and 300 keV, and the corresponding dosages were 2.0 × 1013, 5.0 × 1013, 1.1 × 1014, and 3.0 × 1014 cm−2, respectively. The samples were annealed at temperatures between 1000 and 1480 °C (5 min) under a N2 pressure of 1 GPa using a high-nitrogen-pressure solution system22, where the heating and cooling rates were 27 and 200 °C/min, respectively.

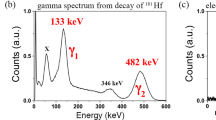

Details on the positron annihilation technique are described elsewhere14,20,23. In the present experiments, the Doppler broadening spectra of the annihilation radiation were measured with high purity Ge detectors as a function of the incident positron energy E. The obtained spectra were characterized by the S parameter, defined as the fraction of annihilation events over the energy range of 510.22‒511.78 keV, and by the W parameter, defined as the number of annihilation events in the energy ranges of 504.14‒507.96 keV and 514.04‒517.86 keV. The energy resolution of the Ge detectors was 1.2 keV (full-width at half-maximum: FWHM). Doppler broadening spectra were also measured with a coincidence system16 in darkness and while the samples were illuminated with a He–Cd laser (wavelength: 325 nm). The obtained S‒E curves were analyzed by VEPFIT, a computer program developed by van Veen et al.24. In the analysis, for the density of the sample, we used a value of 6.15 g/cm3. The application of the VEPFIT code to ion implanted GaN is described elsewhere14,20,23. Doppler broadening spectra corresponding to a delocalized positron and to positrons trapped by typical cation vacancies were calculated using the QMAS (Quantum MAterials Simulator) code25. An orthorhombic supercell equivalent to 4 × 4 × 2 wurtzite cells was used for simulation and it contained 128 atoms if there are no vacancies. The supercell dimensions were \(2\sqrt 3\) a0 × 4 a0 × 2 c0, where a0 = 0.3189 nm and c0 = 0.5186 nm were the experimental lattice parameters of the wurtzite cell. For the supercell containing a defect, atomic positions in the fixed cell were computationally optimized through a series of first-principles calculations. Charge states of the system were assumed to be neutral. Additional information is given in supplementary document and further details on the calculation procedure are given elsewhere25,26.

Results and discussion

Figure 1 shows the values of S parameter of Mg-implanted GaN before and after UHPA as a function of incident positron energy E. The S‒E curve for an unimplanted sample is also shown. The mean implantation depth of positrons is shown on the upper horizontal axis. For unimplanted GaN, the large S value was observed near the surface (E ≅ 0.1 keV) and it decreased with decreasing E. This is due to the annihilation of positrons at the surface and the decrease in the annihilation probability at the surface at high E. From the fitting, the diffusion length of positrons Ld was obtained as 110 ± 3 nm, which corresponds to the one for high-quality GaN14,23. The S value saturated at E > 20 keV, suggesting that almost all positrons annihilated in the bulk in this energy range, and this value was close to the S value for defect-free GaN14,20,23. For the sample annealed at 1480 °C, the S value saturated at E > 2 keV, suggesting that the effect of the positron annihilation at the surface was negligible at this energy range. The saturated S value was close to the S value for defect-free GaN14,20,23. The observed S–E curve for the sample annealed at 1480 °C was close to that for Mg-doped GaN grown by MOVPE27, suggesting a high activation rate of Mg. For the as-implanted sample and ones annealed at 1000–1200 °C, the S values were larger than S for defect-free GaN, which can be attributed to the trapping of positrons by vacancy-type defects.

From the relationship between the S and W values, the defect species detected by positron annihilation can be identified16. Figure 2 shows the (S, W) values measured by using the coincidence system at E = 4 keV for the Mg-implanted GaN before and after annealing. Almost all positrons with this energy were implanted into the region corresponding to the box profile of Mg. The statistical error of the (S, W) values was close to the size of symbols used in the figure. The (S, W) value for unimplanted GaN was measured at E = 28.6 keV, and it was also shown to be the value for the defect-free GaN (denoted as “DF”). The (S, W) values calculated for the annihilation of positrons in the delocalized state [DF(cal.)], typical complexes of Ga-vacancies (VGa) and VN, such as (VGa)m(VN)n, and complexes between vacancies and H are shown (blue symbols). In the figure, the notation “(Hn)Ga” corresponds to VGa containing H atoms, and n is number of H atoms in VGa. “(HGaHN)3” means that one H atom is trapped by VGa and VN, respectively, and each of them forms six-fold complexes. The difference between the (S, W) value for the unimplanted GaN (DF) and the calculated one for defect-free GaN [DF(cal.)] is due to a limitation of the simulation used in the present work. For the as-implanted sample, the (S, W) value was close to the calculated value for VGaVN. Because almost all positrons annihilated in the trapped state in the damaged region for as-implanted GaN14,20,23, the major defect species in this sample can be identified as VGa-related defects such as VGaVN. The same conclusion was reached in previous reports14,20,23,28. After annealing at 1000–1480 °C, the (S, W) values located on the line connecting the values for DF-GaN and (VGaVN)3. This suggests that vacancy clusters such as (VGaVN)3 were introduced at 1000 °C annealing, and their effect on the positron annihilation parameters decreased above 1100 °C. The introduction of the vacancy clusters in the Mg-implanted GaN after annealing without the capping layer was also confirmed in measurements of the positron lifetime spectra23, and the observed annealing behavior of the defects was the same as that for the sample annealed without the capping layer. As mentioned below, a certain amount of H was incorporated in the present sample, and H atoms were considered to be trapped by vacancy-type defects. As shown in Fig. 2, because the S (W) value tended to be decreased (increased) by the trapping of H by vacancies, the size of the vacancies for the sample annealed at 1000 °C could be larger than that of (VGaVN)3.

(S, W) values measured at E = 4 keV using coincidence system (brown symbols). (S, W) for unimplanted GaN is also shown (denoted as defect-free; “DF”). Calculated (S, W) for positron annihilation in delocalized state, DF, VGa, VGa(VN)n, (VGaVN)m, and complexes between vacancies and H [HGa, (H3)Ga, (HGaHN)3, and (VGaHN)4] are also shown (blue symbols), where notation “(Hn)Ga” corresponds to VGa containing H atoms, and n is number of H atoms in VGa. Brown line connects (S, W) values for unimplanted sample and samples annealed above 1000 °C.

Figure 3 shows the annealing behaviors of the S values calculated from the coincidence Doppler broadening profiles measured at E = 4 keV for the Mg-implanted GaN before and after UHPA. Uedono et al.23 reported the results for Mg-implanted GaN annealed with a 300-nm-thick AlN capping layer in N2 gas at atmospheric pressure (1000–1300 °C). The obtained annealing behaviors of the S values for those samples are also shown. For the sample annealed with the capping layer, Mg+ ions were implanted into the sample to obtain 500-nm-box profiles with [Mg] = 1 × 1019 cm−3 at room temperature. The defect species in the sample before annealing was identified as VGa-related defects, which was the same as that for the present sample. No large difference in overall annealing behaviors of S measured in darkness was observed for the samples with and without the capping layer. As discussed above, the increase in the S value for the sample annealed at 1000 °C corresponds to the formation of vacancy clusters. At 1000–1300 °C, the S values for the sample annealed with the capping layer were larger than those for the sample with UHPA, suggesting that the annealing without a capping layer effectively decreased the concentration of vacancy-type defects even at a relatively low annealing temperature (1000 °C).

Annealing behaviors of S for Mg-implanted GaN before and after UHPA. Results for Mg-implanted GaN annealed with protective capping layer are also shown23.

The trapping rate of positrons by vacancy-type defects depends on the defect charge state16. In general, when defects with different charge states coexist in a sample, the trapping of positrons by positively charged defects is negligible. Thus, the observed decrease in the S value for the samples annealed above 1100 °C was attributed to not only a decrease in the size/concentration of vacancy-type defects but also to the downwards shift of the Fermi level position due to Mg activation and a resultant shift of the defect charge state from neutral to positive (or negative to neutral)20,23. The S values for both samples were increased by illumination, which can be attributed to the transition in the charge state of the vacancy-type defects from positive to neutral (or neutral to negative) and a resultant increase in the trapping probability of positrons to such defects20,23,29. The effect of the illumination on the S value for the sample annealed with the capping layer was larger than that for the sample with UHPA, which suggests that the concentration of residual vacancies, which act as acceptors, was high for the sample annealed with the capping layer. This also shows the advantage of the annealing treatment without a capping layer.

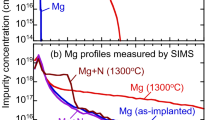

The solid curves in Fig. 1 are fits to the experimental data. In the fitting, the region sampled by positrons was divided into three or four blocks. Derived depth distributions of S are shown in Fig. 4. The Ld value in the first block (the nearest surface region) was determined by the fitting, and the values for the samples annealed at different temperatures were obtained to be 5‒10 nm, which were the typical for materials with high vacancy concentration14,16. The Ld values in other blocks corresponding to the damaged region were fixed to be 10 nm. These values did not significantly influence the obtained depth profiles of S. Figure 5a,b shows the depth distributions of Mg and H measured by SIMS. The incorporation of H in the samples during UHPA was reported by Narita et al.12. They suggested that unintentional moisture may exist in the UHPA chamber, and this caused doping of H into the sample during UHPA. No difference in the Mg distributions for the as-implanted sample and the samples annealed at 1000‒1200 °C was observed. After annealing at 1300 °C, Mg started to diffuse toward the inside of the samples. The Mg distribution for the sample annealed at 1400 °C was identical to that for the sample annealed at 1480 °C. In Fig. 4, for the as-implanted sample and the sample annealed at 1100 °C, the position of the first and second blocks with a high S value (≤ 500 nm) agreed with the box profile of Mg. This can be attributed to the high [Mg] in this region and a resultant high total deposited energy of Mg that was used to replace atoms. In Fig. 4, a damaged region was introduced up to a depth 900‒1300 nm, and this region was deeper than the block profile of Mg. This was due to the introduction of defects by Mg implanted below 300 nm (which can be seen as a tail from the Mg block profile) and the high sensitivity of positrons to vacancy-type defects.

Depth distributions of S obtained from analysis of S–E curves for Mg-implanted GaN (Fig. 1).

In Fig. 5b, for the as-implanted sample, the observed high concentration of H near the subsurface (≤ 200 nm) was due to surface adsorbates. The incorporation of H was observed after annealing at 1000 °C, where the H concentration was high in the region corresponding to the Mg box profile (≤ 300 nm), and it rapidly decreased below 300 nm. The observed box profile of H is unlikely explainable assuming the diffusion model with a constant source at the surface. It is well known that H incorporation is often caused by Mg-doped GaN because of the low formation energy of MgGa-H pairs12,30. For the sample annealed at 1000 °C, vacancy-type defects with a high concentration still remained, and as can be seen in Fig. 5, the concentration of H was higher than that of Mg in this region. Thus, the major cause of the box-shape H distribution could be attributed to the trapping of vacancy-type defects. After 1100 °C annealing, H atoms started to diffuse toward the bulk, and as a result, the H concentration in the subsurface region decreased. A further decrease in the H concentration was observed in the subsurface region after annealing at 1200 °C. As mentioned above, because the surface acted as a sink for vacancies even in this temperature range, the observed change in the H concentration in the subsurface region could be related to the diffusion of vacancy-type defects toward the surface. For this sample, the H concentration in the region between 500 and 900 nm remained high, and this region reasonably agreed with the second block (400–1100 nm) in the depth distribution of S (Fig. 4). This can be attributed to the trapping of H by vacancy-type defects in the deep defect rich region and to a resultant suppression of the out-diffusion of H toward the surface. Because no large change in the depth distribution of Mg was observed up to this annealing temperature (1200 °C), the observed annealing behavior of H did not directly relate to the interaction between Mg and H.

After annealing at 1300 °C, Mg started to diffuse toward the bulk, but it seemed to be suppressed below the deeper defect rich region (400–1100 nm), suggesting that the depth distribution of Mg was influenced by the presence of vacancy-type defects. The H concentration started to increase at this annealing temperature, which was associated with the enhanced incorporation of H during the annealing. Above 1400 °C annealing, both the depth distribution and the concentration of Mg almost coincided with those of H, respectively. In this temperature range, because of the decrease in the vacancy concentration (Fig. 4), the number of Mg atoms at the Ga sites increased, and as a result, the interaction between MgGa and H was likely to enhance the incorporation of H in the sample.

Summary

The positron annihilation technique was used to study behaviors of vacancy-type defects in Mg-implanted GaN annealed without a protective capping layer. The major defect species in the as-implanted GaN was identified as VGa-related defects such as VGaVN. Compared with the results for a sample with a capping layer, the vacancy concentration was decreased by UHPA without the use of a capping layer. This suggests that the surface is an effective sink for vacancy-type defects, and it also shows the superiority of high-temperature annealing with a non-capping layer. The annealing behaviors of vacancies related to the change in the depth distributions of Mg and H, where H was unintentionally incorporated in the sample during UHPA. In the temperature range between 1000 and 1200 °C, no change in the depth distribution of Mg was observed. The depth distribution of H, however, was influenced by vacancy distributions, which was due to the trapping of H by such defects. Above 1300 °C annealing, Mg atoms started to diffuse toward the bulk. In this temperature range, H incorporation was mainly caused by the interaction between MgGa and H. The present research shows that the vacancy-type defects and their annealing behaviors affected the depth distribution of Mg during annealing. Knowledge on the interaction between vacancies, Mg, and H is useful for optimizing the p-type doping process using ion-implantation.

References

Baliga, B. J. Gallium nitride devices for power electronic applications. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 28, 074011 (2013).

Lidow, A., Strydom, J., De Rooij, M. & Reusch, D. GaN Transistors for Efficient Power Conversion (Wiley, New York, 2014).

Amano, H. et al. The 2018 GaN power electronics roadmap. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 51, 163001 (2018).

Hu, J. et al. Materials and processing issues in vertical GaN power electronics. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 78, 75–84 (2018).

Pearton, S. J., Zolper, J. C., Shul, R. J. & Ren, F. GaN: processing, defects, and devices. J. Appl. Phys. 86, 1 (1999).

Kucheyev, S. O., Williams, J. S. & Pearton, S. J. Ion implantation into GaN. Mater. Sci. Eng. 33, 51–107 (2001).

Unland, J., Onderka, B., Davydov, A. & Schmid-Fetzer, R. Thermodynamics and phase stability in the Ga–N system. J. Cryst. Growth 256, 33–51 (2003).

Greenlee, J. D., Anderson, T. J., Feigelson, B. N., Hobart, K. D. & Kub, F. J. Characterization of an Mg‐implanted GaN p–i–n diode. Phys. Stat. Sol. A 212, 2772–2775 (2015).

Oikawa, T., Saijo, Y., Kato, S., Mishima, T. & Nakamura, T. Formation of definite GaN p-n junction by Mg-ion implantation to n−-GaN epitaxial layers grown on high-quality free standing GaN substrate. Nucl. Inst. Methods B 365, 168–170 (2015).

Narita, T., Kachi, T., Kataoka, K. & Uesugi, T. P-type doping of GaN by magnesium ion implantation. Appl. Phys. Exp. 10, 016501 (2017).

Sakurai, H. et al. Highly effective activation of Mg-implanted p-type GaN by ultra-high-pressure annealing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 142104 (2019).

Narita, T. et al. Electric-field-induced simultaneous diffusion of Mg and H in Mg-doped GaN prepared using ultra-high-pressure annealing. Appl. Phys. Express 12, 111005 (2019).

Jacobs, A. G. et al. Role of capping material and GaN polarity on Mg ion implantation activation. Phys. Stat. Sol. A 217, 1900789 (2020).

Uedono, A. et al. Vacancy‐type defects and their annealing behaviors in Mg‐implanted GaN studied by a monoenergetic positron beam. Phys. Stat. Sol. B 252, 2794–2801 (2015).

Van de Walle, C. G. & Neugebauer, J. First-principles calculations for defects and impurities: applications to III-nitrides. J. Appl. Phys. 95, 3851–3879 (2004).

Krause-Rehberg, R. & Leipner, H. S. Positron Annihilation in Semiconductors, Solid-State Sciences, Vol. 127 (Springer, Berlin, 1999).

Tuomisto, F. & Makkonen, I. Defect identification in semiconductors with positron annihilation: experiment and theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 1583–1631 (2013).

Saarinen, K. et al. Observation of native Ga vacancies in GaN by positron annihilation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 3030–3033 (1997).

Saarinen, K., Suski, T., Grzegory, I. & Look, D. C. Thermal stability of isolated and complexed Ga vacancies in GaN bulk crystals. Phys. Rev. B 64, 233201 (2001).

Uedono, A. et al. Study of defects in GaN grown by the two-flow metalorganic chemical vapor deposition technique using monoenergetic positron beams. J. Appl. Phys. 90, 181–186 (2001).

Oila, J. et al. Ga vacancies as dominant intrinsic acceptors in GaN grown by hydride vapor phase epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett 82, 3433–3435 (2003).

M. Boćkowski, P. Strak, I. Grzegory, & S. Porowski. IV 10. High pressure solution growth of GaN. In: Technology of Gallium Nitride Crystal Growth. Springer Series in Materials Science, Vol. 133 (ed. Ehrentraut, D., Meissner, E. & Boćkowski, M.) (Springer, New York, 2010).

Uedono, A. et al. Carrier trapping by vacancy-type defects in Mg‐implanted GaN studied using monoenergetic positron beams. Phys. Stat. Sol. B 255, 1700521 (2018).

van Veen, A. et al. VEPFIT applied to depth profiling problems. Appl. Surf. Sci. 85, 216–224 (1995).

Ishibashi, S., Tamura, T., Tanaka, S., Kohyama, M. & Terakura, K. Ab initio calculations of electric-field-induced stress profiles for diamond/c: B N (110) superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 76, 153310 (2007).

Ishibashi, S. et al. Computational study of positron annihilation parameters for cation mono-vacancies and vacancy complexes in nitride semiconductor alloys. Condens. Matter 31, 475401 (2019).

Uedono, A. et al. Defect characterization in Mg-doped GaN studied using a monoenergetic positron beam. J. Appl. Phys. 111, 014508 (2012).

Uedono, A. et al. Annealing properties of vacancy-type defects in ion-implanted GaN studied by monoenergetic positron beams. J. Appl. Phys. 102, 084505 (2007).

Uedono, A. et al. Electron capture by vacancy-type defects in carbon-doped GaN studied using monoenergetic positron beams. Thin Solid Films 639, 78–83 (2017).

Lyons, J. L., Janotti, A. & Van de Walle, C. G. Shallow versus deep nature of Mg acceptors in nitride semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 156403 (2012).

Acknowledgements

A part of this work was also supported by MEXT “Research and development of next-generation semiconductor to realize energy-saving society” Program Grant Number JPJ005357 and the Polish National Science Centre through project No. 2018/29/B/ST5/00338.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Uedono wrote the main manuscript text and figures. All authors discussed contents of manuscript and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Uedono, A., Sakurai, H., Narita, T. et al. Effects of ultra-high-pressure annealing on characteristics of vacancies in Mg-implanted GaN studied using a monoenergetic positron beam. Sci Rep 10, 17349 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74362-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74362-9

This article is cited by

-

Dopant activation process in Mg-implanted GaN studied by monoenergetic positron beam

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.