Abstract

Chronic diffuse body pain is unequivocally highly prevalent in Veterans who served in the 1990–91 Persian Gulf War and diagnosed with Gulf War Illness (GWI). Diminished motor cortical excitability, as a measurement of increased resting motor threshold (RMT) with transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), is known to be associated with chronic pain conditions. This study compared RMT in Veterans with GWI related diffuse body pain including headache, muscle and joint pain with their military counterparts without GWI related diffuse body pain. Single pulse TMS was administered over the left motor cortex, using anatomical scans of each subject to guide the TMS coil, starting at 25% of maximum stimulator output (MSO) and increasing in steps of 2% until a motor response with a 50 µV peak to peak amplitude, defined as the RMT, was evoked at the contralateral flexor pollicis brevis muscle. RMT was then analyzed using Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance (RM-ANOVA). Veterans with GWI related chronic headaches and body pain (N = 20, all males) had a significantly (P < 0.001) higher average RMT (% ± SD) of 77.2% ± 16.7% compared to age and gender matched military controls (N = 20, all males), whose average was 55.6% ± 8.8%. Veterans with GWI related diffuse body pain demonstrated a state of diminished corticomotor excitability, suggesting a maladaptive supraspinal pain modulatory state. The impact of this observed supraspinal functional impairment on other GWI related symptoms and the potential use of TMS in rectifying this abnormality and providing relief for pain and co-morbid symptoms requires further investigation.

Trial registration: This study was registered on January 25, 2017, on ClinicalTrials.gov with the identifier: NCT03030794. Retrospectively registered. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03030794.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gulf War Illness (GWI) is a chronic multisymptomatic illness that uniquely affects military personnel of the 1990–91 Persian Gulf War. An estimated 25–32% of the 700,000 Veterans returning from theater in the Persian Gulf have exhibited a sequela of symptoms characterized by GWI. These symptoms include neurological dysfunction, gastrointestinal, respiratory, or dermatological issues as well as pain and fatigue1,2. Of those, chronic pain has been one of the most debilitating conditions and appears to be inseparable for those who were diagnosed with Gulf War Illness3,4,5. While the pathophysiology underlying pain symptomology has not been well defined, it is well known that chronic pain states are associated with diminished intrinsic supraspinal pain modulatory function which often presents as reduced motor cortical excitability6,7,8,9,10. On the other hand, increased motor cortical excitability is known to be associated with enhanced pain inhibition11. Thus, assessing the underlying motor cortical excitability in patients with GWI related diffuse body pain including headaches, muscle, and joint pain can offer a new level of understanding in the illness and potentially provide guidance for therapeutic intervention for this patient population. While it is widely accepted that chronic pain states can be associated with impaired corticomotor excitability represented by a diminished supraspinal modulatory state from traumatic or non-traumatic causes6,7,8,12,13,14, to the authors’ best knowledge, no study has been conducted to assess the corticomotor excitability in patients with GWI related chronic diffuse body pain including headaches, joint, and muscle pain.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) can evoke action potentials on the cerebral cortex, and is one of the most established methods for assessing motor cortical excitability via the measurement of the resting motor threshold (RMT), defined as the minimum percentage of the maximum intensity needed to elicit a motor response demonstrated on an electromyogram15,16,17,18. In addition, it provides a potential therapeutic option in rectifying supraspinal neoplastic and maladaptive changes occurring in chronic pain syndromes19,20,21,22.

To further the understanding of the pathophysiology of pain associated with GWI, this study compared RMT in Veterans with GWI-associated chronic headaches, muscle, and joint pain, with gender and age matched controls who served in the same period and region but did not exhibit these pain symptoms, hypothesizing that cortical excitability of the motor cortex is suppressed in patients with GWI.

Methods

Veterans who served in the Persian Gulf War I between August 1990 and July 1991 were screened and enrolled based on the study protocol approved by the Institutional Human Subject Protection Committee. All methods were carried out in accordance with the approved protocol. The study consisted of three visits as follows: (1) Informed Consent and Screening; (2) MRI Scan; and (3) Resting Motor Threshold Procedure with TMS. On average, study participants completed all three visits within 2 weeks.

Screening and demographics

The main study inclusion criteria consisted of male or female Veterans between the ages of 18 and 65 years old who served in the Persian Gulf for at least thirty consecutive days between August 1990 and July 1991. Veterans in the Gulf War Illness-associated headache and pain group (GWV-HAP) were also required to meet the following diagnostic criteria:

-

1.

CDC Criteria for Gulf War Illness (at least 1 symptom in 2 of the following domains)23

-

1.

Pain

-

2.

Fatigue

-

3.

Cognition and Mood

-

1.

-

2.

Kansas Criteria for Gulf War Illness (at least 3 out of the 6 following domains)24

-

1.

Pain

-

2.

Neurologic

-

3.

Fatigue

-

4.

GI Symptoms

-

5.

Respiratory Symptoms

-

6.

Skin Symptoms

-

1.

-

3.

International Headache Society Criteria (ICHD-3) for Migraine Headaches Without Aura25

-

1.

At least 5 headache attacks, fulfilling the following criteria i and ii:

-

i.

Headache attacks lasting 4–72 h

-

ii.

Occupied by nausea and/or photophobia and phonophobia

-

i.

-

1.

In addition, GWV-HAP subjects were required to have an average headache exacerbation intensity greater than or equal to 3/10 on a numerical rating scale (NRS), occurring at least three times a week and at least one of which should have lasted more than four hours in the past three months26. They were also required to have daily muscle pain with an intensity of greater than or equal to 3/10 on a NRS and daily joint pain with an intensity of greater than or equal to 3/10 on a NRS26.

Age and gender matched Veterans who met the initial study criteria of a male or female Veteran between 18 and 65 years old who served in the Persian Gulf for at least thirty consecutive days between August 1990 and July 1991, but did not meet both GWI diagnostic criteria and the pain conditions defined above for GWV-HAP group were recruited for the Gulf War Veterans (GWV) Control group. GWV Control group were gender and age-matched within one year to the GWV-HAP group.

Veterans were excluded from either GWV-HAP or GWV Control groups of the study if they had any of the following: pregnancy; history of pacemaker implant; any ferromagnetic material in the brain and/or body; history of dementia; major psychiatric diseases; life threatening diseases; presence of any chronic neuropathic pain; history of seizures; pending litigation; low back pain with mechanical origins; lack of ability to understand or speak English; history of traumatic brain injury; chronic tension or cluster headaches; or ongoing cognitive rehabilitation or treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

After subjects were enrolled into the study, demographic information pertaining to age, gender, race, body mass index (BMI), and Persian Gulf War durations and duties were collected. Those who served in the 1990–91 Persian Gulf War were indicated as serving under “Gulf War I,” whereas those who served in both the 1990–91 Persian Gulf War and post-1991 Gulf War were indicated as “Both.” Time served in the Persian Gulf was reported in months. Military branches were reported as either Navy, Marines, Army, or Other, with “Other” consisting of the Coast Guard and Air Force branches. Combat status was reported based on military occupational specialty, with combat roles coded as “C” and non-combat roles coded as “NC”.

Neuroimaging data acquisition

Neuroimaging data was acquired through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using a General Electric Discovery MR750 3.0T scanner. During the scan, subjects were instructed to keep the head still and padding was provided between the subject’s head and the scanner head coil to minimize head movement. Anatomical scans were obtained with magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MP RAGE) samplings (176 slices, T1 450, TE 3.172, TR (ms) 8.132, 256 × 256 and 1 mm slice thickness).

Study procedure: resting motor threshold

Preparation

Subjects were asked to sit in a comfortable chair and relax as much as possible. Electromyography (EMG) recordings (Xltek, Oakville, Ontario, Canada) were collected through silver-silver chloride surface electrodes attached to the contralateral flexor pollicis brevis muscle and a 3 cm diameter ground electrode placed on the back of the hand. Manufacturer preinstalled software was used to collect signal with a recording time window of 200 ms, gain of 100 μV, notch filter 60 Hz, LFF 20 Hz, and HFF 10 k Hz. TMS was performed with a figure-of-eight Cool-B65 coil connected to MagPro R30 (Alpine BioMed, Fountain Valley, CA, USA).

TMS neuronavigation system

All anatomical MRI images were processed using BrainVoyager TMS Neuronavigation Software (Brain Innovation, Maastricht, The Netherlands), in which anatomical scans were oriented along the anterior commissure (AC) and posterior commissure (PC) plane. The transformed images were used to create 3D head and brain meshes, where head fiducial points (FDP) were marked. Utilizing the BrainVoyager ultrasound-based co-registration system via sensors attached to each subject’s face and the TMS coil, stereotaxic data was used to determine the spatial position of the TMS stimulation site in relation to each subject. A digitizing pen with ultrasound sensors was used to mark each subject’s face, which was co-registered to corresponding FDPs on a subject’s head mesh. As a result, the TMS coil was visualized in real time and space, allowing the investigator to focus the magnetic flux on a specific target region.

Resting motor threshold

Under the guidance of BrainVoyager Neuronavigation, a constant suprathreshold stimulus intensity was applied from the TMS coil on the left primary motor cortex (LMC) in an ascending order. Given the pain symptoms in this patient population are diffuse, the laterality of the testing side was chosen for the ease of operation and location derived from previous pain related studies. A coil holder (Alpine BioMed, Fountain Valley, CA, USA) with three joints (two of which are ball joint) was used to hold the coil in place during the assessment. A single pulse TMS was delivered to the LMC starting at 25% of maximum stimulator output (MSO) and increasing in steps of 2% until a motor response at the flexor pollicis brevis muscle of 50 µV peak to peak amplitude in five out of ten consecutive trials was evoked. Each pulse was delivered at 20–30 s apart to minimize any potential lingering effect from the preceding pulses. The maximum vertical coil-to-target distance was recorded and the horizontal distance between the center of the magnetic flux and the cortical target was kept under 5 mm during each pulse delivery27,28,29. The MSO of the MagPro R30 used in this procedure was 1850 V, and the minimum stimulus required for the evoked response was defined as the resting motor threshold (RMT)30. The cortical location for flexor pollicis brevis muscle was obtained by using the personalized brain mesh to trace the precentral gyrus region corresponding to the contralateral hand in the homunculus layout, which was confirmed using the EMG. All assessments were conducted in the same ambient (temperature and lighting) setting between 10 am and 2 pm during weekdays.

Data analysis

The within subject design was used for this study. All subjects in GWV-HAP group were age and gender matched to a counterpart control group, and there was no significant difference between them on these measurements using Chi-Square for categorical data and Analysis of Variance for continuous data. Furthermore, these two groups were not significantly different on race, Gulf War period, duration, number of deployments, military branch, combat status, or BMI. The primary outcome, resting motor threshold (RMT) data, was normally distributed and analyzed using Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance (RM-ANOVA) with one within-factor of headache and pain using SPSS version 23.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All research subjects provided informed consent for the study. The research protocol was approved by the Veteran’s Affairs San Diego Healthcare System Institutional Review Board for Human Research Protection.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of clinical details was obtained from the patients.

Results

Demographics

Forty-seven Veterans were screened based on the study protocol approved by the Institutional Human Subject Protection Committee. Out of the forty-seven Veterans, one failed the study screening, five dropped prior to study procedures due to time commitment or MRI complications, and one was excluded due to information shared after the study procedures that would exclude him or her from the study. The remaining forty gender and age-matched Veterans (20 GWV-HAP and 20 GWV Control) were enrolled in the study and their data analyzed. On average, the average age of Veterans (years old ± SD) in the GWV-HAP (N = 20, all males) group was 50.7 ± 4.2 years old, serving an average duration (months ± SD) of 7.9 ± 8.7 months in the Persian Gulf over 1.6 ± 1.2 (numbers ± SD) of deployments (Table 1). The average age of Veterans (years old ± SD) in the GWV Control group (N = 20, all males) were 50.8 ± 4.2 years old and served 8.2 ± 3.8 months in the Persian Gulf with 1.3 ± 0.6 number of deployments (Table 2). All subjects were male in both groups. Five Veterans in the GWV-HAP group served in both Gulf War I and post-1991 Gulf War periods, whereas four in the GWV Control group served in both wars. The remaining Veterans served in only Gulf War I. The GWV- HAP group consisted of twelve Caucasians, three Asians, two African-Americans, two Hispanics, and one Pacific Islander, whereas the GWV Control group consisted of eleven Caucasians, five African-Americans, two Hispanics, one Pacific Islander, and one African-American/Asian. In the GWV-HAP group, nine Veterans were in the Navy branches, seven in the Marines, three in the Army, and one in Other, compared to ten Navy, six Marine, and four Army subjects in the GWV Control group. Eight subjects in the GWV-HAP group were in Combat (C) roles, compared to three subjects in the GWV Control group. The remaining subjects were Non-Combat (NC). Body Mass Index (BMI ± SD) in the GWV-HAP group was higher at 30.3 ± 4.0 compared to the GWV Control group who had an average BMI of 29.8 ± 4.0. BMI data was missing from one subject in the GWV Control group, who was excluded from the calculation of its average.

There were no significant differences found between groups in all demographic categories (see Table 3).

There were no significant differences found between groups in all demographic categories where P = 0.05.

Resting motor threshold

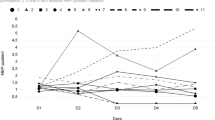

GWV-HAP subjects required a significantly higher level of stimulation to evoke a motor response with an average RMT (% ± SD) of 77.2% ± 16.7% compared to GWV Control subjects whose average RMT (% ± SD) was 55.6% ± 8.8% (f1,19 = 24.24, p < 0.001), with the GWV-HAP subjects showing a median of 75% and range from 50% to 100% and GWV Control showing a median of 55% and range from 35% to 70% (Fig. 1). In addition, there was no significant coil-to-target distance difference between the two groups with the average distance (mm ± SD) at 33.4 ± 8.3 and 33.4 ± 10.2 for GWI-HAP and GWV Control groups respectively.

Box-and-whisker plot of the minimum value, lower quartile, median, mean, upper quartile, and the maximum value of the resting motor threshold amplitude percentages of veterans in the GWV-HAP and GWV-Control groups. Resting motor threshold was determined using electromyograph recordings on the contralateral flexor pollicis brevis muscle with the TMS coil positioned over the primary motor cortex (M1). GWV-HAP: Veterans in the Gulf War Illness-associated headache and pain group; GWV-Control: Gulf War Veterans not experiencing Gulf War Illness and associated headache and pain; **p < 0.001.

Discussion

Supraspinal pain perception consists of mainly three functional regions: (1) sensory discriminatory regions such as the primary and secondary somatosensory cortices (S1 and S2) and inferior parietal lobe (IPL); (2) affective regions such as anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and insula (IN); and (3) modulatory regions involving motor and various regions of prefrontal cortices (PFCs)31,32. Additionally, the insula (IN) has been known to play a role in assessing the magnitude of pain, while the inferior parietal lobe (IPL) aids in distinguishing spatial discrimination in pain perception33,34,35,36. Chronic pain state is often associated with a mal-adaptation in the supraspinal pain processing, which is often accompanied with diminished modulatory functional connectivity from the prefrontal cortices with diminished motor cortex excitability as reflected by an elevated resting motor threshold10,37.

While chronic pain conditions are found in 60–70% of Veterans who have served in the 1990–91 Persian Gulf War in general, for those who met the diagnostic criterial of GWI, the prevalence of chronic pain is 100%5. Given the inseparable relation between GWI and pain, it would be infeasible to assess the illness/syndrome alone without pain.

In addition, in patients with GWI, previous diffusion tensor imaging studies revealed higher mean diffusivity and lower fractional anisotropy values along the corona radiata, corpus callosum, corticospinal tract, internal capsule, anterior and posterior thalamic radiation, fronto-occipital fasciculus, and frontal, temporal, and precentral and postcentral gyri, suggesting possible white matter reorganization or neurodegeneration38,39,40,41. Not only do these regions have known associations to the regulation of nociceptive input and can serve as a connection between hemispheres and cortices of the brain, they also play a role in attention, mood, fatigue, and cognition42,43,44,45,46,47,48. Thus, it will be impossible to assess the one symptom alone at a time without the others in this patient population if the focus is in understanding a common pathophysiology leading to various co-morbid symptoms.

In the current study, GWV-HAP group demonstrated an increase in RMT level compared to their non-pain Gulf War veteran counterparts. The need for a higher level of stimulation in GWV-HAP group is consistent with other chronic pain conditions caused by either direct or indirect neuronal traumas which resulted in impaired supraspinal pain modulation49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57. Although the pathophysiology behind the headaches and diffuse body pain in this population has not been explicitly defined, the observed functional deficit in supraspinal cortical modulatory function serves as a significant step in understanding the pathophysiology underlying the high prevalence of chronic pain states in this patient population, especially for those who meet the diagnostic criteria for GWI58,59,60.

While transcranial magnetic stimulation-evoked resting motor threshold has been demonstrated to be a reliable method for assessing cortical excitability, it may also be a viable solution for the chronic pain experienced by these Veterans. TMS is approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for treating depression and migraine headaches61,62,63. In addition, multiple meta-analyses and panel consensus review definitively supported a high level of evidence for treating central neuropathic states, such as in the management of chronic and debilitating headaches in mild Traumatic Brain Injury patients64,65. High frequency (> 1 Hz) TMS works by evoking action potentials to directly excite the motor cortex and potentially regain cortical excitability, which cannot be accomplished with traditional pharmacological methods19,20,22,66,67. Since Gulf War Veterans with Gulf War Illness-associated headaches and pain present with a similarly increased RMT profile, it is possible they may also find relief with repetitive TMS in the form of increased pain modulatory function.

Limitations to the study include those due to an all-male study population and recruitment from a single site. Although all subjects were successfully gender and age-matched to a control group, all forty Veterans were male which is not indicative of the true Veteran population deployed to the Persian Gulf in 1990–91. While female Veterans were screened for the study, they were far fewer in number compared to male Veterans who met the criteria. This is most likely explained by the inherently male-dominated target population of 1990–91 GWV, of which only 7% of the total deployed personnel consisted of females68. Furthermore, 70–78% of female Veterans reported pain symptoms, meaning only a small number of female Veterans would meet the Control criteria while also living near the recruitment site69,70. Other reasons that may have led to this all-male result include the current distribution of female to male Veterans at the site. Since Veterans with pain required a gender and age matched healthy counterpart, it became less likely that a female was included in the study. Additionally, recruitment occurred primarily in San Diego County, which is heavily dominated by Naval and Marine bases. Future studies would benefit from recruitment from multiple sites as it would provide a study population that is more representative of the 1990–91 Persian Gulf War Veterans in terms of military branches and gender. In addition, there are inherent difficulties in conducting resting motor threshold measurements with TMS as slight variations in skull thickness, hydration, and even amount of hair among the subjects may have a minor effect on these physical parameters. However, having kept the variations in both horizontal and vertical coil-to-target distances at the minimum, the authors reckoned the impact of these individual variations should have been minimized. While circadian factors and sleep pattern may have an impact on motor cortical excitability71, given all RMT assessments in the current study were conducted in the same ambient setting during a 4–5 h day time window and none of the subjects have reported any sleep deprivation events prior to the assessment, the authors reckoned the potential environmental impact on the evaluation was unlikely.

In short, the observed result from the current study suggests that the high prevalence of headaches and diffuse body pain in 1990–91 Persian Gulf War Veterans, especially for those who met the diagnostic criteria of GWI, is associated with impaired cortical excitability and pain modulation. The significance of TMS in this study is two-fold: 1) it can be utilized as a tool for assessing supraspinal maladaptive state associated with the illness; and 2) it can also serve as a potential therapeutic tool in managing this multisymptomatic illness. Assessing the latter will require more well signed randomized controlled studies.

Data availability

The data used and/or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- TMS:

-

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

- GWI:

-

Gulf War Illness

- RMT:

-

Resting motor threshold

- M1:

-

Primary motor cortex

- MSO:

-

Maximum stimulator output

- GWV:

-

Gulf War Veterans

- GWV-HAP:

-

Veterans in the Gulf War Illness-associated headache and pain group

- ICHD-3:

-

International Headache Society Criteria

- NRS:

-

Numerical rating scale

- PTSD:

-

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- C:

-

Combat

- NC:

-

Non-Combat

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MP RAGE:

-

Magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo

- EMG:

-

Electromyography

- AC:

-

Anterior commissure

- PC:

-

Posterior commissure

- FDP:

-

Head fiducial points

- LMC:

-

Left primary motor cortex

- RM-ANOVA:

-

Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance

- SSC1:

-

Primary somatosensory cortices

- SSC2:

-

Secondary somatosensory cortices

- PFCs:

-

Prefrontal cortices

- IN:

-

Insula

- IPL:

-

Inferior parietal lobe

References

White, R. F. et al. Recent research on Gulf War illness and other health problems in veterans of the 1991 Gulf War: effects of toxicant exposures during deployment. Cortex 74, 449–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2015.08.022 (2016).

Steele, L., Sastre, A., Gerkovich, M. M. & Cook, M. R. Complex factors in the etiology of Gulf War illness: wartime exposures and risk factors in veteran subgroups. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1003399 (2012).

Rayhan, R. U., Ravindran, M. K. & Baraniuk, J. N. Migraine in gulf war illness and chronic fatigue syndrome: prevalence, potential mechanisms, and evaluation. Front. Physiol. 4, 181. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2013.00181 (2013).

Kuzma, J. M. & Black, D. W. Chronic widespread pain and psychiatric disorders in veterans of the first Gulf War. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 10, 85–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-006-0017-z (2006).

Lei, K., Metzger-Smith, V., Golshan, S., Javors, J. & Leung, A. The prevalence of headaches, pain, and other associated symptoms in different Persian Gulf deployment periods and deployment durations. SAGE Open Med. 7, 2050312119871418. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312119871418 (2019).

Galhardoni, R. et al. Altered cortical excitability in persistent idiopathic facial pain. Cephalalgia 39, 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102418780426 (2019).

Schabrun, S. M., Burns, E., Thapa, T. & Hodges, P. The response of the primary motor cortex to neuromodulation is altered in chronic low back pain: a preliminary study. Pain Med. 19, 1227–1236. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnx168 (2018).

Thibaut, A., Zeng, D., Caumo, W., Liu, J. & Fregni, F. Corticospinal excitability as a biomarker of myofascial pain syndrome. Pain Rep. 2, e594. https://doi.org/10.1097/PR9.0000000000000594 (2017).

Cosentino, G. et al. Cyclical changes of cortical excitability and metaplasticity in migraine: evidence from a repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Pain 155, 1070–1078 (2014).

Castillo Saavedra, L., Mendonca, M. & Fregni, F. Role of the primary motor cortex in the maintenance and treatment of pain in fibromyalgia. Med. Hypotheses 83, 332–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2014.06.007 (2014).

Granovsky, Y., Sprecher, E. & Sinai, A. Motor corticospinal excitability: a novel facet of pain modulation?. Pain Rep. 4, e725. https://doi.org/10.1097/PR9.0000000000000725 (2019).

Bushnell, M. C., Ceko, M. & Low, L. A. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 502–511. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3516 (2013).

Leung, A. et al. Diminished supraspinal pain modulation in patients with mild traumatic brain injury. Mol. Pain https://doi.org/10.1177/1744806916662661 (2016).

Parker, R. S., Lewis, G. N., Rice, D. A. & McNair, P. J. Is motor cortical excitability altered in people with chronic pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Stimul. 9, 488–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2016.03.020 (2016).

Badawy, R. A., Loetscher, T., Macdonell, R. A. & Brodtmann, A. Cortical excitability and neurology: insights into the pathophysiology. Funct. Neurol. 27, 131–145 (2012).

King, R. et al. Longitudinal assessment of cortical excitability in children and adolescents with mild traumatic brain injury and persistent post-concussive symptoms. Front. Neurol. 10, 451. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00451 (2019).

Li, M. et al. Effect of electro-acupuncture on lateralization of the human swallowing motor cortex excitability in healthy subjects: study protocol for a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Trials 20, 180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3267-x (2019).

Du, J. et al. Aberrances of cortex excitability and connectivity underlying motor deficit in acute stroke. Neural Plast. 2018, 1318093. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1318093 (2018).

Brighina, F., Palermo, A., Daniele, O., Aloisio, A. & Fierro, B. High-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation on motor cortex of patients affected by migraine with aura: a way to restore normal cortical excitability?. Cephalalgia 30, 46–52 (2010).

Chistyakov, A. V. et al. Preliminary assessment of the therapeutic efficacy of continuous theta-burst magnetic stimulation (cTBS) in major depression: a double-blind sham-controlled study. J. Affect. Disord. 170, 225–229 (2015).

Fierro, B. et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) during capsaicin-induced pain: modulatory effects on motor cortex excitability. Exp. Brain Res. 203, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-010-2206-6 (2010).

Lefaucheur, J. P. et al. Analgesic effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex in neuropathic pain: influence of theta burst stimulation priming. Eur. J. Pain 16, 1403–1413. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00150.x (2012).

Fukuda, K. et al. Chronic multisymptom illness affecting Air Force veterans of the Gulf War. JAMA 280, 981–988 (1998).

Steele, L. Prevalence and patterns of Gulf War illness in Kansas veterans: association of symptoms with characteristics of person, place, and time of military service. Am. J. Epidemiol. 152, 992–1002 (2000).

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 38, 1–211, doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102417738202 (2018).

Williamson, A. & Hoggart, B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J. Clin. Nurs. 14, 798–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01121.x (2005).

Reijonen, J., Saisanen, L., Kononen, M., Mohammadi, A. & Julkunen, P. The effect of coil placement and orientation on the assessment of focal excitability in motor mapping with navigated transcranial magnetic stimulation. J. Neurosci. Methods 331, 108521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2019.108521 (2020).

Leung, A. et al. Left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex rTMS in alleviating MTBI related headaches and depressive symptoms. Neuromodulation 21, 390–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/ner.12615 (2018).

Leung, A. et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in managing mild traumatic brain injury-related headaches. Neuromodulation https://doi.org/10.1111/ner.12364 (2015).

Khedr, E. M. et al. Longlasting antalgic effects of daily sessions of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in central and peripheral neuropathic pain. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 76, 833–838. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2004.055806 (2005).

Apkarian, A. V., Bushnell, M. C., Treede, R. D. & Zubieta, J. K. Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur. J. Pain 9, 463–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.11.001 (2005).

Tracey, I. Nociceptive processing in the human brain. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 15, 478–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2005.06.010 (2005).

Neugebauer, V., Galhardo, V., Maione, S. & Mackey, S. C. Forebrain pain mechanisms. Brain Res. Rev. 60, 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.014 (2009).

Tracey, I. Neuroimaging of pain mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Support Palliat Care 1, 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0b013e3282efc58b (2007).

Seifert, F. et al. A functional magnetic resonance imaging navigated repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation study of the posterior parietal cortex in normal pain and hyperalgesia. Neuroscience 170, 670–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.07.024 (2010).

Moulton, E. A., Pendse, G., Becerra, L. R. & Borsook, D. BOLD responses in somatosensory cortices better reflect heat sensation than pain. J. Neurosci. 32, 6024–6031. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0006-12.2012 (2012).

Mhalla, A., de Andrade, D. C., Baudic, S., Perrot, S. & Bouhassira, D. Alteration of cortical excitability in patients with fibromyalgia. Pain 149, 495–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.03.009 (2010).

Van Riper, S. M. et al. Cerebral white matter structure is disrupted in Gulf War Veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain 158, 2364–2375. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001038 (2017).

Rayhan, R. U. et al. Increased brain white matter axial diffusivity associated with fatigue, pain and hyperalgesia in Gulf War illness. PLoS ONE 8, e58493. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058493 (2013).

Voss, H. U. et al. Possible axonal regrowth in late recovery from the minimally conscious state. J. Clin. Investig. 116, 2005–2011. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI27021 (2006).

Bosch, B. et al. Multiple DTI index analysis in normal aging, amnestic MCI and AD. Relationship with neuropsychological performance. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.02.004 (2012).

Taylor, W. D., MacFall, J. R., Gerig, G. & Krishnan, R. R. Structural integrity of the uncinate fasciculus in geriatric depression: relationship with age of onset. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 3, 669–674 (2007).

Pardini, M., Krueger, F., Raymont, V. & Grafman, J. Ventromedial prefrontal cortex modulates fatigue after penetrating traumatic brain injury. Neurology 74, 749–754. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d25b6b (2010).

Tajima, S. et al. Medial orbitofrontal cortex is associated with fatigue sensation. Neurol. Res. Int. 2010, 671421. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/671421 (2010).

Aron, A. R., Fletcher, P. C., Bullmore, E. T., Sahakian, B. J. & Robbins, T. W. Stop-signal inhibition disrupted by damage to right inferior frontal gyrus in humans. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 115–116. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1003 (2003).

Weissman, D. H. & Prado, J. Heightened activity in a key region of the ventral attention network is linked to reduced activity in a key region of the dorsal attention network during unexpected shifts of covert visual spatial attention. Neuroimage 61, 798–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.032 (2012).

Matsushita, M., Hosoda, K., Naitoh, Y., Yamashita, H. & Kohmura, E. Utility of diffusion tensor imaging in the acute stage of mild to moderate traumatic brain injury for detecting white matter lesions and predicting long-term cognitive function in adults. J. Neurosurg. 115, 130–139. https://doi.org/10.3171/2011.2.JNS101547 (2011).

Gu, L. et al. Detection of white matter lesions in the acute stage of diffuse axonal injury predicts long-term cognitive impairments: a clinical diffusion tensor imaging study. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 74, 242–247. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3182684fe8 (2013).

Caeyenberghs, K., Siugzdaite, R., Drijkoningen, D., Marinazzo, D. & Swinnen, S. P. Functional connectivity density and balance in young patients with traumatic axonal injury. Brain Connect. 5, 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1089/brain.2014.0293 (2015).

Levin, H. S. et al. Mental state attributions and diffusion tensor imaging after traumatic brain injury in children. Dev. Neuropsychol. 36, 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/87565641.2010.549885 (2011).

Ljubisavljevic, M. et al. Central changes in muscle fatigue during sustained submaximal isometric voluntary contraction as revealed by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 101, 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/0924-980x(96)95627-1 (1996).

Pal, D. et al. Diffusion tensor tractography indices in patients with frontal lobe injury and its correlation with neuropsychological tests. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 114, 564–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.12.002 (2012).

Palacios, E. M. et al. Diffusion tensor imaging differences relate to memory deficits in diffuse traumatic brain injury. BMC Neurol. 11, 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-11-24 (2011).

Tallus, J., Lioumis, P., Hamalainen, H., Kahkonen, S. & Tenovuo, O. Long-lasting TMS motor threshold elevation in mild traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurol. Scand. 126, 178–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0404.2011.01623.x (2012).

Tallus, J., Lioumis, P., Hamalainen, H., Kahkonen, S. & Tenovuo, O. Transcranial magnetic stimulation-electroencephalography responses in recovered and symptomatic mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 30, 1270–1277. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2012.2760 (2013).

Bernabeu, M. et al. Abnormal corticospinal excitability in traumatic diffuse axonal brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 26, 2185–2193. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2008.0859 (2009).

Ah Sen, C. B. et al. Active and resting motor threshold are efficiently obtained with adaptive threshold hunting. PLoS ONE 12, e0186007. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186007 (2017).

Amourette, C. et al. Gulf War illness: effects of repeated stress and pyridostigmine treatment on blood-brain barrier permeability and cholinesterase activity in rat brain. Behav. Brain Res. 203, 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2009.05.002 (2009).

Ferguson, E. & Cassaday, H. J. Theoretical accounts of Gulf War Syndrome: from environmental toxins to psychoneuroimmunology and neurodegeneration. Behav. Neurol. 13, 133–147. https://doi.org/10.1155/2002/418758 (2001).

Lewine, J. D. et al. Objective documentation of traumatic brain injury subsequent to mild head trauma: multimodal brain imaging with MEG, SPECT, and MRI. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 22, 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HTR.0000271115.29954.27 (2007).

George, M. S., Taylor, J. J. & Short, E. B. The expanding evidence base for rTMS treatment of depression. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 26, 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835ab46d (2013).

Lipton, R. B. & Pearlman, S. H. Transcranial magnetic simulation in the treatment of migraine. Neurotherapeutics 7, 204–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurt.2010.03.002 (2010).

Lefaucheur, J. P. et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Clin. Neurophysiol. 125, 2150–2206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2014.05.021 (2014).

Leung, A. et al. rTMS in alleviating mild TBI related headaches–a case series. Pain Physician 19, E347-354 (2016).

Leung, A. et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in managing mild traumatic brain injury-related headaches. Neuromodulation 19, 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/ner.12364 (2016).

Fumal, A. et al. Induction of long-lasting changes of visual cortex excitability by five daily sessions of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in healthy volunteers and migraine patients. Cephalalgia 26, 143–149 (2006).

Hosomi, K. et al. Cortical excitability changes after high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for central poststroke pain. Pain 154, 1352–1357 (2013).

Coughlin, S. S. et al. A review of epidemiologic studies of the health of gulf war women veterans. J. Environ. Health Sci. https://doi.org/10.15436/2378-6841.17.1551 (2017).

Nahin, R. L. Severe pain in veterans: the effect of age and sex, and comparisons with the general population. J. Pain 18, 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2016.10.021 (2017).

Haskell, S. G., Heapy, A., Reid, M. C., Papas, R. K. & Kerns, R. D. The prevalence and age-related characteristics of pain in a sample of women veterans receiving primary care. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 15, 862–869. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2006.15.862 (2006).

Ly, J. Q. M. et al. Circadian regulation of human cortical excitability. Nat. Commun. 7, 11828. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11828 (2016).

Funding

This study received funding support from the following agency: Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program Grant (W81XWH-16-1-0754).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.L., A.K., and V.M.S. assisted in conducting the study, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. S.G. assisted in the study design, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. J.J. and J.W. assisted in patient evaluation, recruitment, and screening. R.L. assisted in neuroimaging assessment. M.V. assisted in conducting the study and patient evaluation. T.R. assisted in patient evaluation. A.L. designed and conducted the study and assisted in manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, K., Kunnel, A., Metzger-Smith, V. et al. Diminished corticomotor excitability in Gulf War Illness related chronic pain symptoms; evidence from TMS study. Sci Rep 10, 18520 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75006-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75006-8

This article is cited by

-

Ocular and inflammatory markers associated with Gulf War illness symptoms

Scientific Reports (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.