Abstract

Large-scale layers peeling after the laser irradiation of dual ion beam sputtering coatings is discovered and a model is established to explain it. The laser damage morphologies relate to the laser fluence, showing thermomechanical coupling failure at low energy and coating layers separation at high energy. High-pressure gradients appear in the interaction between laser and coatings, resulting in large-scale layer separation. A two-step laser damage model including defect-induced damage process and ionized air wave damage process is proposed to explain the two phenomena at different energy. At relatively high energies (higher than 20 J/cm2), ionization of the air can be initiated, leading to a peeling off effect. The peeling effect is related to the thermomechanical properties of the coating materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optical coatings can increase the transmittance and reflectance of optical elements such as glass and lenses, which are widely used in various laser systems1,2,3. Sputtered coatings have excellent mechanical properties and stability, which are suitable for use in space laser systems4,5. Generally, laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) of dielectric coatings materials is lower than the damage threshold of bulk materials6,7. The laser damage problem of dielectric coatings is a key factor in laser systems8,9. The laser damage of the sputtered coatings is related to the launch and operation stability of the entire spacecraft mission10,11. The research on the mechanism of laser and sputtered coatings is very important.

Nanosecond laser damage is usually attributed to structural defects or absorptive defects12,13. Nanoprecursors that initially induce damage are difficult to characterize or observe14,15. Analysis of the laser damage morphology can reveal the mechanism behind the damage phenomenon16,17,18. Research on bulk materials such as fused silica found that the multi-longitudinal mode laser interacts with fused silica to form a ripple structure19,20,21, which is related to the laser excited air electrons22. Diaz et al. find that the action mechanism of fused silica in vacuum under laser irradiation is related to the ionization of SiO2 material on the surface to form a plasma, which also has a ripple structure23,24. This phenomenon of laser-excited air or surface matter forming a plasma correlates with the wavelength of the laser25. A 1ω frequency laser is more likely to excite air than a 3ω laser26. The ripple structure does not appear when the electron beam evaporated coatings interacts with laser, and it mainly manifests as surface ablation27. The high temperature of the ionizing wave causes the surface of the evaporated coatings to ablate quickly28. The research on the interaction mechanism between the sputtered coatings and laser is rare.

In this work, two different laser damage morphologies of dual ion beam sputtering coatings with high-resolution characterization reveal different damage mechanisms, one of which is large-area film separation. The damage morphologies are related to the laser energy, which show thermomechanical coupling failure at low energy and coating layers separation at high energy. The damage features of sputtering coatings are different from the ring patterns of fused silica or the surface scalding of the e-beam evaporation coatings. High-pressure gradients appear in the interaction between laser and coatings, resulting in large-scale layer separation. Different layer stress parameters make the peeling off effect different. A two-step laser damage model including defect-induced damage process and ionized air wave damage process is proposed to explain the two phenomena.

Experiments

Coatings preparation

The fused silica (HPFS 7980, Corning) substrates have no absorption band between 185 and 2500 nm. The index of refraction of substrates is 1.45 and transmittance is above 94% at 1064 nm. The cylindrical substrates have a radius of 25 mm and a thickness of 5 mm. Detailed materials and optical properties of three different coatings (Al2O3/SiO2, Ta2O5/SiO2 and Nb2O5/SiO2) are shown in the Table 1. Before coating, ultrasonic and chemical etching should be used to clean the substrate, mainly to remove surface contamination and polishing deposition contamination of the substrates. Dual ion beam sputtering equipment (Veeco, Ltd.) is used to deposit multilayer coatings.

Laser-induced damage parameters

In the experiment, the 1-on-1 laser damage performance test is carried out according to the standard ISO 2125429. The schematic diagram of laser damage test platform is shown in Fig. 1. The incident angle of laser to three samples is 0 degree. Sample I and II are tested on laser exit surface. Sample III is tested on laser incident surface. The pulse width of Nd: YAG laser is 12 ns at 1064 nm (1ω). The facula radius of the incident laser on the coatings is about 200 μm at 1/e2 of the maximum intensity. In the laser damage experiment, there are 20 points irradiated by each energy step. The online CCD (charge coupled device) and offline optical microscope can be used to evaluate whether the test area is damaged.

Experimental results and analysis

Laser damage probability

Laser damage probability distribution of the Al2O3/SiO2 coatings is shown in Fig. 2. It can be obtained that within 30 J/cm2 energy, the probability of laser damage is low, and is about 40% around 70 J/cm2. The two-stage damage probability indicates that there are two different defects. One has a lower density but is prone to laser damage, and the other has a higher density but requires higher energy.

Laser damage morphology

Optical microscope (Leica) and optical profiler (Veeco) are used to characterize laser damage morphologies. Morphologies and damage pits depth of Al2O3/SiO2 coatings are shown in Fig. 3(c) and (d) correspond to the depth distribution of (a) and (b), respectively. Figure 3(a) is single defect-induced damage, and (b) is multiple defect-induced damage. Obvious peeling off of coatings layer is observed, and no change in the color of the plasma ablation is observed. From the depth profile of Fig. 3(d), the damage depth is about 1.2 μm, which is close to the substrate. The defects of sample I is possible from interface of coatings and substrate.

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM; Zeiss) is used to characterize the microscopic morphology of damage pits. Figure 4(a–c) show the damage morphologies of Al2O3/SiO2 coatings at near damage threshold, medium energy, and high energy, respectively. Figure 4(d) and (e) are enlarged views of the central regions of (b) and (c), respectively. Laser damage near the threshold appears as thermal–mechanical coupling failure. The diameter of the damage pit is about 3 μm. The edge contour of the damage pit is clear and shows brittleness distortion, which indicates that the defects are far away from the coatings surface and the thermal effect is not obvious. The central thermal–mechanical coupling damage pit can still be observed at medium energy in Fig. 4(d), but the surrounding coatings are extensively damaged, which is manifested as peeling off. At high energy, the central damage pit is not deeper and only appears as more thermodynamic ablation. The area of ablation and damage of the surrounding peeling layers is larger.

Ta2O5/SiO2 and Nb2O5/SiO2 coatings also show a similar phenomenon, that is, they only show thermal damage at low energy, and at high energy, in addition to thermal damage, the coatings show peeling off effect. The critical energy density of the three coatings is about 20 J/cm2.

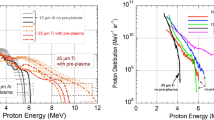

Figure 5 indicates that the size of the damage pit changes with the laser energy. Some damage pits of sample I and II are observed at relatively low energy, which are relatively small, especially sample I. Sample III is not damaged at relatively low energy, so no damage point was observed at relatively low energy. The damage pit size becomes significantly larger after energy above about 20 J/cm2, and with the increase of energy, the development of damage pit size approaches a linear increase. Under the same laser energy, sample I has the largest damage pit size, and sample III has the smallest size. This is related to the thermodynamic properties of the film composition of the samples, which will be explained in detail later.

Damage mechanism

To explain the correlation between the occurrence of the peeling effect and the laser fluence at 1064 nm. Compared with the shock wave model proposed by Fabbro et al. for the shock wave caused by the laser irradiated material30, the shock wave is generated in the solid material, and the propagation speed is the speed of sound level. The propagation speed of shock waves in solid materials is much lower than the surface destruction speed. Therefore, the model we propose is to ionize air to generate plasma, and the speed of expansion and propagation in the air is in the same order of magnitude as the speed of destruction in the experiment. The possible formation of air laser supported detonation waves (LSD) is considered31. This happens when the free electron energy E can excite the neutral substance in the medium (mainly composed of O2 and N2 molecules) to ionize32. At the beginning of ionization, the maximum energy obtained by the electrons cannot be higher than the following value33:

Among the Eq. (1), I is the laser light intensity, λ is the laser wavelength, The energy of air molecules (mainly N2 and O2) ionized by laser is 12 eV. Equation (1) can be used to calculate the laser power density required for ionizing air as 2.14GW/cm2 at 1064 nm. According to the conversion formula (\(F = 0.5\sqrt {\pi /\ln 2I\tau }\)) of laser energy density and power density, the energy density of the laser can be obtained as 27.34 J/cm2. Laser damage will cause the temperature of the coating material around the defect to rise sharply and the absorption will increase34,35. The LSD wave front will absorb and reflect the laser34,36,37,38, making the initial electron avalanche ionization energy lower than 27.34 J/cm2, which is about 20 J/cm2 in our experiment.

Thus, when the energy is low, the laser energy is lower than the ionization energy of the air, and no LSD wave in air can be generated. At this time, the laser and film defects interact with each other, and the defects absorb the laser energy, resulting in thermomechanical coupling damage, such as Fig. 4(a). Due to the deeper defects of the sample II compared to sample I and the strong layer binding force, the thermal effect is more obvious and the damage area is larger in the process of the sample II absorbing the thermal coupling effect of the defect. When the laser energy is greater than the ionization energy of air, LSD waves are generated in the air. Thus, the large-scale emergence of peeling off of coatings is related to a propagation of LSD wave, which is similarly with ring-pattern damage morphologies of the fused silica bulk material39. According to the experimental data in Fig. 5, the velocity of propagation of peeling off can be obtained as 21 km/s (laser energy: 70 J/cm2, maximum diameter: 500 μm), which is equivalent to the speed of a surface shock wave23. Multi-layer coatings deposited by dual ion beam sputtering usually possess high compressive residual stress40. The temperature of laser-induced plasma is higher than 104 K, and the pressure is higher than 1 GPa41. The laser-induced stress wave propagates horizontally and vertically in the coatings and reflects at the boundary of the coatings, thereby changing the residual stress field of the coatings. At the same time, when the stress wave propagates far away from the center of the laser spot, it attenuates exponentially, and gradually disperses. A stress field distribution similar to the shape of Airy Pattern is formed in the coatings32. At the same time, due to the high temperature gradient brought by the LSD wave, the samples are prone to peeling off. Thermodynamic parameters will affect the peeling size of the samples.

The separation of the coating layers originates from the changes in the local stress of different coating layers after the temperature rises, considering the case where the temperature has not reached the melting and vaporization of the coating layers. The change of coatings stress caused by temperature can be explained by the following formula42:

Among them, αc, νc, and Ec are the thermal expansion coefficient, Poisson’s ratio and Young modulus of different coating material. ΔT is the amount of change in temperature rise. Table 2 shows the mechanical parameters of SiO2, Al2O3, Ta2O5, and Nb2O5 coating materials43,44. The stress change caused by the same temperature change in the Al2O3 layer, Ta2O5, and Nb2O5 are 63.59 times, 13.53 times, and 8.99 times that of SiO2 layer, respectively. This explains that sample I which contains Al2O3/SiO2 layers is more likely to occur peeling effect caused by temperature rise. Thus, the peeling off size of sample I is relatively larger.

Therefore, the laser-induced damage of dual ion beam sputtering coatings is mainly divided into two processes, as shown in the Fig. 6. The first step is the defect absorbing laser energy to induce damage, as can be seen in Fig. 6(a). In nanosecond laser damage realm, the distribution of defects is random, and the laser intensity is Gaussian, so the laser intensity of the defect location is random, and the size of the damage pit is also random. In the defect-induced damage process, damage morphology is also correlated with the thermomechanical parameters of the coatings, the type of defect, number of defects in the spot range, and the distribution depth of defect. In the interaction with the laser, the defect absorbs heat, and the local coatings is melted and gasified, resulting in initial damage to the film. Deeper defects require more layers to be destroyed, and the thermal coupling time is longer and the scale of the laser damage is larger.

The second step is the damage of ionized air waves, as shown in the Fig. 6(b), which only occurs at relatively high energies. Air is a wide band gap dielectric, which is basically transparent to the laser, and basically does not absorb laser energy. In the first step, the broken pieces and residual bonds become the precursor of the ionized air, providing the initial seed electrons. Electron avalanche occurs during laser irradiation, resulting in severe ionization of air and formation of plasma. Plasma almost completely absorbs laser energy. The heated gas expands to form a spherical shock wave in all directions, and the air is heated to dozens of eV. The ionization front expands, forming a temperature gradient, and then the film undergoes stress peeling off.

Conclusion

The phenomenon of peeling damage of the dual ion beam sputtering coatings was found and explained. A two-step laser damage model is proposed, including defect-induced damage process and ionized air wave damage process. At relatively high energies (higher than 20 J/cm2), ionization of the air can be initiated, leading to a peeling off effect. The peeling effect is correlated with the thermomechanical properties of the coatings materials. For coatings with large stress differences, the peeling off effect is more serious. This article is helpful for the analysis of the damage process of the dual ion beam sputtering coatings, which can help improve the ability to resist laser damage from a process and design perspective.

References

Liu, H., Jensen, L., Ma, P. & Ristau, D. Stress compensated anti-reflection coating for high power laser deposited with IBS SiO2 and ALD Al2O3. Appl. Surf. Sci. 476, 521–527 (2019).

Kozlov, A. A., Lambropoulos, J. C., Oliver, J. B., Hoffman, B. N. & Demos, S. G. Mechanisms of picosecond laser-induced damage in common multilayer dielectric coatings. Sci. Rep.-UK 9, 1–15 (2019).

Chambonneau, M. et al. Positive-and negative-tone structuring of crystalline silicon by laser-assisted chemical etching. Opt. Lett. 44, 1619–1622 (2019).

4Bartels, N., Allenspacher, P. & Riede, W. Laser conditioning of UV anti-reflective optical coatings for applications in aerospace. Proc. SPIE 10805, 108051Q1 (2018).

Guo, K. et al. Effects of ion beam etching of fused silica substrates on the laser-induced damage properties of antireflection coatings at 355 nm. Opt. Mater. 90, 172–179 (2019).

6Chorel, M. et al. Experimental validation of the robust optimization algorithm for high-fluence optical coatings. OIC ThA, ThA. 5 (2019).

Grua, P., Lamaignère, L., Chambonneau, M., Courchinoux, R. & Néauport, J. Nanosecond laser damage initiation at 0.35 μm in fused silica. Opt. Lett. 43, 2692–2695 (2018).

8Riede, W., Wernham, D., Schröder, H., Allenspacher, P. & Bartels, N. Qualification of laser optics for challenging space LIDAR missions. LAC CM3C, CM3C. 1 (2019).

Guo, K. et al. Effects of structural defects on laser-induced damage of 355-nm high-reflective coatings sputtered on etched substrates. Opt. Mater. 89, 173–177 (2019).

Lux, O. et al. High-power and frequency-stable ultraviolet laser performance in space for the wind lidar on Aeolus. Opt. Lett. 45, 1443–1446 (2020).

Lamaignère, L., Chambonneau, M., Diaz, R., Courchinoux, R. & Donval, T. Laser damage resistance qualification of large optics for high power laser. Proc. SPIE 9345, 934508 (2015).

Cui, Y., Yi, K., Guohang, H. & Shao, J. Interface characteristics of peeling-off damages of laser coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 290, 71–79 (2014).

Naghilou, A., Armbruster, O. & Kautek, W. Femto-and nanosecond pulse laser ablation dependence on irradiation area: The role of defects in metals and semiconductors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 418, 487–490 (2017).

Wang, H. et al. Suppression of nano-absorbing precursors and damage mechanism in optical coatings for 3ω mirrors. Opt. Lett. 41, 1209–1212 (2016).

Shen, C., Chambonneau, M., Cheng, X. A., Xu, Z. & Jiang, T. Identification of the formation phases of filamentary damage induced by nanosecond laser pulses in bulk fused silica. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 111101 (2015).

Chen, H. et al. Laser plasma-induced damage characteristics of Ta2O5 films. Opt. Mater Express 9, 3132–3145 (2019).

Mouskeftaras, A. et al. Direct measurement of ambipolar diffusion in bulk silicon by ultrafast infrared imaging of laser-induced microplasmas. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 041107 (2016).

Chambonneau, M. et al. Laser-induced damage morphology in fused silica at 1064 nm in the nanosecond regime. Proc. SPIE 9237, 923715 (2014).

Chambonneau, M., Grua, P., Rullier, J.-L., Natoli, J.-Y. & Lamaignère, L. Parametric study of the damage ring pattern in fused silica induced by multiple longitudinal modes laser pulses. J. Appl. Phys. 117, 103101 (2015).

Diaz, R. et al. Influence of longitudinal mode beating on laser-induced damage in fused silica. Opt. Lett. 39, 674–677 (2014).

Chambonneau, M., Richter, D., Nolte, S. & Grojo, D. Inscribing diffraction gratings in bulk silicon with nanosecond laser pulses. Opt. Lett. 43, 6069–6072 (2018).

Lamaignère, L. et al. Correlation between laser-induced damage densities of fused silica and average incubation fluences at 1064 nm in the nanosecond regime. J. Appl. Phys. 121, 045306 (2017).

Diaz, R. et al. Influence of vacuum on nanosecond laser-induced surface damage morphology in fused silica at 1064 nm. Appl. Surf. Sci. 362, 290–296 (2016).

Chambonneau, M. et al. Investigations on laser damage growth in fused silica with simultaneous wavelength irradiation. Appl. Opt. 54, 1463–1470 (2015).

Chambonneau, M. & Lamaignère, L. Multi-wavelength growth of nanosecond laser-induced surface damage on fused silica gratings. Sci. Rep.-UK 8, 1–10 (2018).

Chambonneau, M., Rullier, J.-L., Grua, P. & Lamaignère, L. Wavelength dependence of the mechanisms governing the formation of nanosecond laser-induced damage in fused silica. Opt. Express 26, 21819–21830 (2018).

Wang, H. et al. Intrafilm separation of solgel film under nanosecond irradiation. Appl. Opt. 54, 10504–10509 (2015).

Wang, H. et al. Origin of the plasma scalds in dielectric coatings induced by 1 ω laser. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 141603 (2016).

29ISO Standard 21254. Lasers and Laser-Related Equipment: Test Methods for Laser-Induced Damage Threshold (ISO, Switzerland, 2011).

Fabbro, R., Fournier, J., Ballard, P., Devaux, D. & Virmont, J. Physical study of laser-produced plasma in confined geometry. J. Appl. Phys. 68, 775–784 (1990).

Ramsden, S. & Savic, P. A radiative detonation model for the development of a laser-induced spark in air. Nature 203, 1217–1219 (1964).

Carr, C., Bude, J. & DeMange, P. Laser-supported solid-state absorption fronts in silica. Phys. Rev. B 82, 184304 (2010).

Zel’Dovich, Y. B. & Raizer, Y. P. Physics of Shock Waves and High-Temperature Hydrodynamic Phenomena (Dover publications, New York, 2002).

Papernov, S. & Schmid, A. Two mechanisms of crater formation in ultraviolet-pulsed-laser irradiated SiO2 thin films with artificial defects. J. Appl. Phys. 97, 114906 (2005).

Pu, Y. et al. Mechanism for atmosphere dependence of laser damage morphology in HfO2/SiO2 high reflective films. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 023111 (2012).

Demos, S. G., Negres, R. A., Raman, R. N., Rubenchik, A. M. & Feit, M. D. Material response during nanosecond laser induced breakdown inside of the exit surface of fused silica. Laser Photonics Rev. 7, 444–452 (2013).

Boling, N., Dubé, G. & Crisp, M. Morphological asymmetry in laser damage of transparent dielectric surfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 21, 487–489 (1972).

Sun, W. et al. Nanosecond laser pulse induced concentric surface structures on SiO2 layer. Opt. Express 22, 2948–2954 (2014).

Chambonneau, M. et al. Origin of the damage ring pattern in fused silica induced by multiple longitudinal modes laser pulses. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 021121 (2014).

Pond, B. J., DeBar, J., Carniglia, C. K. & Raj, T. Stress reduction in ion beam sputtered mixed oxide films. Appl. Opt. 28, 2800–2805 (1989).

Harris, C. D., Shen, N., Rubenchik, A. M., Demos, S. G. & Matthews, M. J. Characterization of laser-induced plasmas associated with energetic laser cleaning of metal particles on fused silica surfaces. Opt. Lett. 40, 5212–5215 (2015).

Qiu, S. et al. Impact of laser-contaminant interaction on the performance of the protective capping layer of 1 ω high-reflection mirror coatings. Appl. Opt. 54, 8607–8616 (2015).

Chen, H.-C., Huang, C.-Y. & Cheng, P.-W. Stress mechanisms of SiO2 and Nb2O5 thin films sputtered on flexible substrates investigated by finite element method. Surf. Coat Tech. 344, 449–457 (2018).

Shang, P., Xiong, S., Li, L., Tian, D. & Ai, W. Investigation on thermal stability of Ta2O5, TiO2 and Al2O3 coatings for application at high temperature. Appl. Surf. Sci. 285, 713–720 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the China-Italy Intergovernmental Cooperation Project under the National Key R&D program of China (2018YFE0118000), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 11904376), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U1831211), Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research, through the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in the frame of the Italian-Chinese Project of Great Relevance PGR01013 “Effects of space environment on optical and electronic devices for astrophysical space missions”, NSAF Fund Jointly set up by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Chinese Academy of Engineering Physics (No. U1630140), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) (2017289), and the Strategic Priority Research Program of CAS (Grant No. XDB1603).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.G. wrote the main manuscript text. Y.W. revised the manuscript. R.C. and Y.Z. provided suggestions for revision. A.S., M.Z., K.Y., H.H. and J.S. provided an experimental platform. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, K., Wang, Y., Chen, R. et al. Laser-induced layers peeling of sputtering coatings at 1064 nm wavelength. Sci Rep 11, 3783 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80304-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80304-2

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.