Abstract

Magnetite is the main constituent of iron oxide–apatite (IOA) deposits, which are a globally important source of Fe and other elements such as P and REE, critical for modern technologies. Geochemical studies of magnetite from IOA deposits have provided key insights into the ore-forming processes and source of mineralizing fluids. However, to date, only qualitative estimations have been obtained for one of the key controlling physico-chemical parameters, i.e., the temperature of magnetite formation. Here we reconstruct the thermal evolution of Andean IOA deposits by using magnetite thermometry. Our study comprised a > 3000 point geochemical dataset of magnetite from several IOA deposits within the Early Cretaceous Chilean Iron Belt, as well as from the Pliocene El Laco IOA deposit in the Chilean Altiplano. Thermometry data reveal that the deposits formed under a wide range of temperatures, from purely magmatic (~ 1000 to 800 °C), to late magmatic or magmatic-hydrothermal (~ 800 to 600 °C), to purely hydrothermal (< 600 °C) conditions. Magnetite cooling trends are consistent with genetic models invoking a combined igneous and magmatic-hydrothermal origin that involve Fe-rich fluids sourced from intermediate silicate magmas. The data demonstrate the potential of magnetite thermometry to better constrain the thermal evolution of IOA systems worldwide, and help refine the geological models used to find new resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetite (Fe3O4) forms under a wide range of pressure and temperature conditions in igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic environments, as well as in a variety of magmatic and hydrothermal ore deposits. Geochemical studies of magnetite from a wide range of mineral deposits have demonstrated that physico-chemical parameters such as temperature, pressure and oxygen fugacity (ƒO2) control its minor and trace element budget, particularly for Ti, V, Mn, Cr, Mg and Al1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Therefore, the geochemical composition and microtextural features of magnetite provide key information that helps elucidate the formation environment and the chemical evolution of magnetite-bearing deposits5,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16.

Magnetite is the main constituent of iron oxide–apatite (IOA) ore deposits, commonly referred to as Kiruna-type deposits, which can host hundreds of millions to several billion tonnes of magnetite. The microtextures and trace element and isotopic compositions of magnetite samples from Andean IOA deposits have been widely studied10,11,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. These studies scaffold a framework to better understand the ore-forming processes, revealing that the Fe ore forms by mechanisms that involve growth of magnetite under a wide range of conditions, spanning from high-temperature, purely igneous settings, to lower-temperature, fluid-dominated hydrothermal environments. Despite these advances, the thermal evolution of IOA deposits remains poorly constrained and, to date, obtaining quantitative temperature data directly from magnetite mineralization has been challenging. This raises uncertainties on genetic models proposed to explain the genesis of Andean IOA deposits, which over the years have invoked: (1) immiscible Fe-, P-, and carbonate-sulfate-rich melts29,30,31,32,33; (2) metasomatic replacement17,34,35; and (3) magmatic-hydrothermal processes10,11,21,24,25,36,37. Temperature estimations for Andean IOA deposits have been determined using oxygen isotope thermometry between magnetite-actinolite and magnetite-pyroxene pairs19,23,24,27,29, thermometry of magnetite-ilmenite pairs38, actinolite thermometry based on Fe contents19,22,27, and fluid and melt inclusion thermometry in apatite, pyroxene, quartz, anhydrite and calcite11,33,39,40,41,42. However, temperature data obtained directly from magnetite in these deposits are either scarce or unavailable.

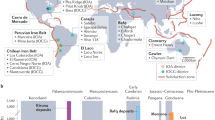

In this study, we use the trace element concentration of magnetite to provide a quantitative estimation of temperature during the evolution of Andean IOA deposits. We apply the Canil and Lacourse43 magnetite thermometer (TMg-mag), which is based on Mg and Fe concentrations, to a comprehensively compiled magnetite EMPA and LA-ICP-MS database. The temperature data were obtained from > 3000 analyses of magnetite from IOA deposits in the world-class Early Cretaceous Chilean Iron Belt, and the Pliocene El Laco deposit in the Central Andes (Fig. 1). We also tested the applicability of the magnetite thermometer by coupling temperature determinations with trace element data (Ti, V and Ga) and micron- to nano-scale observations of magnetite grains in each deposit. This allowed us to confirm the robustness of this thermometer, as well as elucidating micro-analytical uncertainties that lead to temperature overestimations and potential misinterpretations.

Location of the main iron oxide–apatite (IOA) deposits within the Early Cretaceous Chilean Iron Belt, and the Pleistocene El Laco volcanic complex in the Chilean Altiplano. Modified from Palma et al.26.

Sources of data and methods

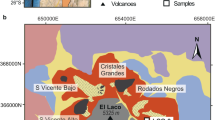

A total of 3126 EMPA and LA-ICP-MS spot analyses of magnetite from different Andean IOA deposits (Table S1) were compiled and used for thermometry calculations. The samples were collected from several deposits in the Early Cretaceous Chilean Iron Belt, including Los Colorados 10,11,44, El Romeral22,26, Cerro Negro Norte28, Carmen, Fresia and Mariela26, as well as the Pliocene Laco Norte and Laco Sur magnetite bodies21,25. In each deposit, the cited studies have recognized a variety of magnetite types based on their microtextures and chemical composition26. Magnetite textures vary from pristine and inclusion-free, to grains that contain abundant mineral inclusions, Fe-Ti lamellar exsolutions, oscillatory and sector zoning, symplectite, and dissolution, reequilibration and recrystallisation textures. These textural features provide insights into magmatic, hydrothermal and syn- and post-mineralization reequilibration processes, as well as a general assessment of the temporality of the different magnetite types. For the sake of simplicity, and to maintain consistency with the magnetite parageneses described in the literature, we homogenized the terminology of the main magnetite textural types according to temporality, from the earliest- to the latest-formed, i.e., Mgt-1, -2, -3, -4 (Table S2). Detailed descriptions for each deposit and their magnetite types can be found in the Supplemental Material (Appendix 1, 2).

Temperature calculations were carried out using the TMg-mag thermometer by Canil and Lacourse43, which is based on the observation that XMg = [Mg/(Mg + Fetotal)] in magnetite is strongly dependent on temperature. These authors experimentally demonstrated that the Mg concentration in magnetite is more dependent on temperature, and relatively insensible to ƒO2 changes, than other trace elements (Al, Mn, Cr, Ni) for a wide range of P–T–X–ƒO2 conditions, in both magmatic and hydrothermal environments. Hence, temperatures were calculated here by using the Fe and Mg concentrations of magnetite determined by EMPA and LA-ICP-MS (Tables S1), and the following empirical calibration, which considers an uncertainty of ± 50 °C43:

The calculated temperature data were coupled with trace element data (Ti, V, Ga) and magnetite temporality based on microtextural observations. Typically, these elements are enriched in igneous magnetite and their concentrations increase systematically with increasing temperature1,2,3,4,5. This allowed us to differentiate between the multiple magnetite types in each deposit. Based on textural relations and trace element concentrations, a decreasing temperature (T) trend is expected from the earliest to the latest magnetite generations (e.g., TMgt-1 > TMgt-2 > TMgt-3 > TMgt-4). A statistical summary of Ti, V and Ga concentrations and calculated temperatures are presented in Table S3.

In addition to magnetite from Cretaceous IOA deposits, we determined crystallisation temperatures (TMg-mag) for two Fe orebodies (Laco Norte and Laco Sur) and the andesitic host rock from the Pliocene El Laco deposit using published data4,20. This allowed us to have a direct temperature reference of the igneous magnetite to compare with temperatures obtained for magnetite from the orebodies using the TMg-mag thermometer.

Results

Calculated magnetite crystallisation temperatures for IOA deposits at the Chilean Iron Belt and El Laco are plotted in Figs. 2a and 3a, respectively. In addition, the median concentrations of Ti, V and Ga in magnetite are plotted for the same deposits (Figs. 2b, 3b). Detailed microtextural data are available for most deposits, including paragenetic relations among magnetite types (temporality), as well as observable variations with depth (Table S2). However, in a few cases (e.g., Carmen and Fresia), no clear temporality between magnetite types has been reported.

Calculated temperatures and median concentrations of selected trace elements in magnetite from IOA deposits of the Chilean Iron Belt. (a) Temperatures calculated using the TMg-mag thermometer43. Uncertainties (error bars) are at ± 50 °C. (b) Titanium, V and Ga median concentrations determined by LA-ICP-MS, except for Los Colorados in which EMPA (Ti, V) and LA-ICP-MS (Ga) data were used.

Calculated temperatures and median concentrations of selected trace elements in magnetite from El Laco orebodies and its andesitic host rocks. (a) Temperatures calculated using the TMg-mag43 thermometer. Uncertainties (error bars) in TMg-mag are at ± 50 °C. (b) Titanium, V and Ga median concentrations determined by LA-ICP-MS.

Figure 2a shows the calculated temperatures for magnetite orebodies in the Chilean Iron Belt. Crystallisation temperatures for magnetite from the Los Colorados IOA deposit mostly range between ~ 850 and ~ 500 °C, with Mgt-1, Mgt-2, Mgt-3 and Mgt-4 configuring a cooling trend with averages values of ~ 730 °C, ~ 630 °C, ~ 600 °C and ~ 620 °C, respectively. Calculated temperatures for El Romeral magnetite vary from ~ 780 to 380 °C in the deep zone to ~ 600 to 340 °C in the shallow zone. In both zones, paragenetically early Mgt-1 yields higher average temperatures than late Mgt-2. In Cerro Negro Norte, temperatures range from ~ 700 to ~ 320 °C, and the average temperatures for the different magnetite generations (Mgt-1 to Mgt-4) range from ~ 570 to ~ 450 °C. Magnetite from Mariela yields temperatures that range from ~ 720 to ~ 420 °C, and an average temperature of ~ 650 °C for Mgt-1, ~ 520 °C for Mgt-2 and ~ 590 °C for Mgt-3. Finally, magnetite from the Carmen and Fresia deposits yield a similar range of calculated temperatures, i.e., ~ 750 to 440 °C and ~ 750 to 360 °C, respectively, and a similar average temperature of ~ 600 °C for both deposits.

Temperatures for the Laco Norte and Laco Sur orebodies at the El Laco deposit mostly range between ~ 900 and ~ 400 °C (Fig. 3a). The temperature range for the deep, intermediate and shallow zones are similar for both orebodies. For the three zones and the different magnetite types (Mgt-1 to Mgt-4), the average calculated temperatures range between ~ 700 °C and ~ 800 °C. The shallow/surface zone shows a wide dispersion with calculated temperatures between ~ 940 and ~ 400 °C. Temperatures for magnetite in the andesite host rocks, on the other hand, range between ~ 960 and ~ 620 °C, and the average temperatures are between ~ 900 °C and ~ 670 °C (Fig. 3a, lower panel).

Discussion

Temperature trends in Andean IOA deposits

The temperature data obtained for magnetite from IOA deposits within the Chilean Iron Belt reveal a distinct cooling trend that broadly correlates with the relative depth of formation or structural level of emplacement of the deposits26. The deep, intrusive-type Los Colorados deposit has the highest calculated temperatures (~ 850–500 °C; Fig. 2a). Intermediate temperatures (~ 780–340 °C) characterise the transitional El Romeral deposit, followed by lower temperatures (~ 700–320 °C) in the hydrothermal-type Cerro Negro Norte deposit (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, temperatures for early magnetite (Mgt-1) within each deposit are consistently higher than the other late textural types in most deposits (Fig. 2a). In Los Colorados, El Romeral and Mariela, this decreasing temperature trend correlates with trace element concentrations, most notably Ti, V and Ga, which are higher in Mgt-1 (Fig. 2b).

In Los Colorados, the high magnetite temperatures are consistent with oxygen isotope thermometry data (> 850 °C to ~ 610 °C), and re-homogenization temperatures of polycrystalline inclusions (> 950 °C) in Mgt-111,19. In addition, the core-to-rim temperature gradient—TMgt-1 (~ 730 °C) > TMgt-2 (~ 630 °C) > TMgt-3 (~ 600 °C)—agrees with the qualitative magnetite cooling path determined by using the [Ti + V] vs. [Al + Mn] concentration plot3,5,9 (Fig. S1). The latter was interpreted by Knipping et al.10,11 as the result of cooling from high-temperature, magmatic-hydrothermal (> 600 °C) to lower temperature hydrothermal conditions (< 600 °C). Notably, hydrothermal magnetite (Mgt-4) from the late-stage stockwork event at Los Colorados44 yields a similar average temperature (~ 620 °C; Fig. 2a) to those determined for the late-stage rims; Mgt-2 and Mgt-3 (~ 630 and 600 °C; Fig. 2a), formed over Mgt-1 cores in the massive magnetite orebodies.

Magnetite temperature data for El Romeral, reveal that the Ga concentration can be used to discriminate between magnetite from the high-temperature deep zone and the lower-temperature shallow zone (Figs. 2, S2). Furthermore, temperatures from the deep zone correlate well with those determined by the composition of primary actinolite grains at 1 kbar (~ 805 to ~ 735 °C)22. In Cerro Negro Norte, the average temperature for early Mgt-1 is consistently higher (~ 572 °C), although data for the other textural types (Mgt-2 to -4) cluster within average temperatures of ~ 520 to 450 °C (Fig. 2a). Pegmatitic-type IOA deposits such as Mariela, Carmen and Fresia (~ 750 to 360 °C; Fig. 2a) exhibit evidence of widespread dissolution-reprecipitation processes, which have been interpreted as caused by multiple pulses of both magmatically-derived and externally-derived meteoric fluids and/or basinal brines26,45. Fluid inclusion studies by Velasco and Tornos42 at Carmen are consistent with this notion, suggesting the involvement of aqueous-gas rich, high-salinity (> 30 wt.% NaCl eq) Ca–Cl–Mg fluids with temperatures > 360 ºC. Average crystallisation temperatures for magnetite from Carmen and Fresia (~ 600 °C; Fig. 2a) are consistent with oxygen isotope thermometry temperatures determined for coeval magnetite-actinolite pairs in Carmen42.

Temperature data for magnetite from El Laco andesitic host rocks provide further insights into the conditions of magnetite crystallisation from a silicate melt. Magnetite in the unaltered host andesite4, which is undoubtedly of igneous origin20,29, crystallised at higher temperatures (~ 960–820 °C) than magnetite from the orebodies (~ 900–400 °C; Fig. 3a). Magnetite samples from the Laco Norte and Laco Sur orebodies at El Laco yield crystallisation temperatures that are similarly variable (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, no major temperature variations are observed with depth or with the temporality of magnetite types in these orebodies. Despite the relatively high average calculated temperature of magnetite from the shallow/surface zone (up to ~ 940 °C), a lower temperature “tail” (~ 400–350 °C) that corresponds with a depletion in Ti-V-Ga is observed (Fig. 3a,b). Previous studies reported high temperatures at El Laco as documented by fluid inclusion thermometry. Temperatures of ~ 840 to ~ 700 °C and high salinities (0.2–59 wt.% NaCl eq.) were obtained from fluid inclusions in clinopyroxene and apatite intergrown with magnetite39,40. Recently, Bain et al.33 reported liquid–vapor homogenization temperatures between ~ 951 and 800 °C for polycrystalline inclusions in diopside-magnetite-anhydrite veins from the El Laco Pasos Blancos orebody. These temperatures overlap with those estimated from oxygen isotope thermometry in the diopside-magnetite-anhydrite veins (~ 1125 to 900 °C)29.

Thermal evolution and genetic implications

Figure 4 presents a schematic representation of magmatic-hydrothermal stages illustrating the thermal evolution for Andean IOA deposits. We coupled the magnetite thermometry data reported here with reference temperatures calculated for magnetite crystallisation in igneous rocks (basalt, andesite, dacite) and other magmatic/magmatic-hydrothermal ore systems including Fe-Ti, V deposits, skarn and porphyry Cu-Mo-Au deposits20,46,47 (Figs. 4a, S3; Table S4). The new temperature data for magnetite presented here are consistent with a magmatic-hydrothermal origin for Andean IOA deposits. The magnetite thermometry data agree with δ56Fe and δ18O stable isotope data for magnetite in several IOA deposits in Chile that are consistent with magnetite crystallising from high-temperature fluids sourced from silicate melts18,19,23,24,34,37,48. Furthermore, the data correspond well with 56Fe and 18O isotope information for several other IOA deposits worldwide, formed under different tectonic settings in different epochs. These include IOA deposits in the Kiruna and Gräsbergerg districts in Sweden, the Bafq District, Iran, and the Pea Ridge and Pilot Knob deposits in Missouri, USA, among others23,48,49,50.

Thermal evolution of Andean IOA deposits unraveled by magnetite thermometry data. Stages 1 and 2 are characterised by purely magmatic (~ 1000 to 800 °C) and magmatic-hydrothermal (~ 800 to 600 °C) temperature conditions, respectively. Stage 3 comprises purely hydrothermal (< 600 °C) conditions. (a) Reference temperatures of magnetite for igneous rocks (basalt, andesite, dacite), and magmatic/magmatic-hydrothermal (Fe–Ti, V, skarn, porphyry Cu–Mo–Au) ore deposits, and low-temperature (T) hydrothermal magnetite (replacement and disseminated); (b,c) thermal evolution of El Laco (b) and IOA deposits from the Chilean Iron Belt (c). See text for discussion.

Our proposed model in Fig. 4 invokes a combination of magmatic and hydrothermal processes to explain the thermal evolution of IOA deposits in continental arc settings. Stage 1 comprises purely igneous magnetite crystallisation from a hydrous silicate melt, reflected by temperatures of ~ 1000 to 800 °C. During this stage, upward migration of magma to 3–4 km depth26 results in decompression-induced volatile saturation of the silicate melt, facilitated by heterogenous nucleation onto magnetite microlites10,11,51,52,53. Decompression allows an efficient separation of the Fe-rich magmatic volatile phase from the parental magma reservoir and its rapid transfer to upper levels through faults, forming tabular, massive magnetite bodies such as those found at Los Colorados10,26. During stage 2 (~ 800–600 ºC), the dissolved FeCl2 in the exsolved magmatic-hydrothermal fluid precipitates as magnetite upon cooling, which is more efficient under higher degrees of decompression22,54. Mineralization styles include stockwork and breccias, typical of systems dominated by high water/rock ratios (e.g., El Romeral, Cerro Negro Norte, deep/intermediate zones of El Laco). Stage 3 involves magnetite precipitation from cooling hydrothermal fluids at temperatures below 600 °C, with variable contributions from available external fluids, e.g., meteoric fluids and/or basinal brines23,55. During this stage, multiple injections of fluids lead to complex magnetite growth, with increased dissolution-reprecipitation processes and formation of pegmatitic bodies and pervasive replacement horizons, e.g., Carmen, Fresia, Mariela, El Laco21,26,45.

The thermal trends recorded in magnetite in the studied orebodies suggest that Andean IOA deposits were formed predominantly under high-temperature magmatic-hydrothermal (~ 800–600 °C) conditions that grade to lower temperature hydrothermal conditions (< 600 °C; Fig. 4b,c). These results agree with most recent studies in IOA systems18,19,23,24,26,37 and similarly to other magnetite-bearing magmatic-hydrothermal deposits such as skarns and porphyry Cu-Mo-Au systems8,9,16,46 (Fig. 4a).

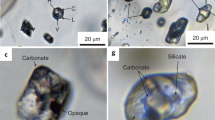

Considerations for magnetite thermometry in ore systems

The crystallisation temperatures reported in this study, calculated from a database of over 3000 magnetite analyses, are unequivocally consistent with geological observations and independent temperature estimations in the studied deposits, confirming the robustness of the magnetite thermometer. We highlight that the proper application of the TMg-mag thermometer depends not only on a good experimental and empirical calibration43, but also relies on detailed textural studies, including identification of chemical zonation, exsolution, Mg-bearing nano- to micro-sized inclusions and domains, as well as oxidation products (hematite, maghemite, goethite). These features are frequently observed and particularly affect magnetite in ore deposits due to the significant hydrothermal and chemical weathering overprinting in these systems. Therefore, it is likely that some of the temperatures calculated in this study may be representative of multiple episodes of hydrothermal circulation, leading to higher average temperatures. For example, magnetite from the intermediate zone in El Laco21 yields high calculated temperatures of up to ~ 940 °C (Fig. 3a), possibly due the abundance of micron- to nano- scale Mg-bearing silicate particles (Table S2). Thus, it is likely that hydrothermal processes such as fluid-aided dissolution-reprecipitation lead to variations in the calculated temperatures attributable to complex magnetite textures in some deposits (e.g., El Laco, Carmen, Fresia). This may result in an overestimation of the Mg concentration in magnetite and consequently higher calculated temperatures, where the average Mg concentration in magnetite corresponds to the sum of Mg in the magnetite matrix and silicate nano-inclusions44. Additionally, variable degrees of magnetite low-temperature oxidation and replacement by maghemite, hematite and goethite—typically found at shallow levels at El Laco (Mgt-3 and-4; Table S2)—could explain the wide range of magnetite temperatures (~ 950–390 °C Fig. 3a). Accordingly, relatively high-Mg and low-Ti, V, Ga contents of these magnetite grains (Fig. 3b) reflect extensive chemical modification.

Final remarks

We reconstructed the thermal evolution of Andean iron oxide–apatite (IOA) deposits by using the TMg-mag thermometer on a large magnetite geochemical dataset. Our results are the first comprehensive assessment of the thermal evolution of IOA deposits, providing a quantitative estimation of cooling trends in several IOA deposits of variable size and types. Calculated magnetite temperatures record a transition from purely igneous (~ 1000 to 800 ºC) to mainly hydrothermal conditions (< 600 °C). Our data support a genetic model that invokes a magmatic-hydrothermal origin for Andean IOA deposits, and most importantly, reveal a predominance of fluid-dominated hydrothermal conditions. Our results demonstrate that magnetite thermometry opens new avenues to constrain formation temperatures in IOA systems, and therefore could be useful for vectoring towards magnetite-rich zones laterally and vertically, and for inferring the presence of deeper mineralized orebodies.

Methods

Several analytical techniques were used to characterise the textures and quantify the composition of magnetite from massive orebodies in Andean IOA deposits10,11,21,22,25,26,28,44, and only a brief description is presented here. Identification and characterisation of magnetite textures, as well as the selection of sample sites for EMPA and LA-ICP-MS analyses, were performed by using a scanning electron microscope (SEM). Electron probe microanalyses (EMPA) and laser ablation inductively coupled plasma spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) were used to quantify the abundances of major (e.g., Mg, Al, Si, Ca, Ti, V, Cr, Fe, Mn) and trace elements (e.g., Na, Mg, Al, Si, P, Ca, Cr, Mn, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, V, Ti, Ga) in magnetite samples, respectively. The complete database of magnetite compositions (Fe, Mg, Ti, V, Ga) is provided in Table S1.

Crystallisation temperatures of magnetite from Andean IOA deposits were obtained by using the TMg-Mag thermometer43, which is applicable to both igneous and hydrothermal magnetite. Calculations were performed using the empirical calibration: TMg-Mag (°C) = –8344(± 322)/[lnXMg – 4.1 (± 0.28)] – 273, in which XMg = Mg/(Mg + Fetotal), and considering an uncertainty of ± 50 °C.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information.

References

Toplis, M. J. & Corgne, A. An experimental study of element partitioning between magnetite, clinopyroxene and iron-bearing silicate liquids with particular emphasis on vanadium. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 144, 22–37 (2002).

Bordage, A. et al. V oxidation state in Fe–Ti oxides by high-energy resolution fluorescence-detected X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Miner. 38, 449–458 (2011).

Dupuis, C. & Beaudoin, G. Discriminant diagrams for iron oxide trace element fingerprinting of mineral deposit types. Miner. Deposita 46, 319–335 (2011).

Dare, S. A. et al. Trace elements in magnetite as petrogenetic indicators. Miner. Deposita 49, 785–796 (2014).

Nadoll, P., Angerer, T., Mauk, J. L., French, D. & Walshe, J. The chemistry of hydrothermal magnetite: A review. Ore Geol. Rev. 61, 1–32 (2014).

Sievwright, R. H., Wilkinson, J. J., O’Neill, H. S. C. & Berry, A. J. Thermodynamic controls on element partitioning between titanomagnetite and andesitic–dacitic silicate melts. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 172, 62 (2017).

Sievwright, R. H., O’Neill, H. S. C., Tolley, J., Wilkinson, J. J. & Berry, A. J. Diffusion and partition coefficients of minor and trace elements in magnetite as a function of oxygen fugacity at 1150 °C. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 175, 40 (2020).

Hu, H. et al. Reequilibration processes in magnetite from iron skarn deposits. Econ. Geol. 111, 1–8 (2015).

Nadoll, P., Mauk, J. L., Leveille, R. A. & Koenig, A. E. Geochemistry of magnetite from porphyry Cu and skarn deposits in the southwestern United States. Miner. Deposita 50, 493–515 (2015).

Knipping, J. L. et al. Giant Kiruna-type deposits form by efficient flotation of magmatic magnetite suspensions. Geology 43, 591–594 (2015).

Knipping, J. L. et al. Trace elements in magnetite from massive iron oxide–apatite deposits indicate a combined formation by igneous and magmatic-hydrothermal processes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 171, 15–38 (2015).

Liu, P. P., Zhou, M. F., Chen, W. T., Gao, J. F. & Huang, X. W. In situ LA-ICP-MS trace elemental analyses of magnetite: Fe-Ti-(V) oxide-bearing mafic-ultramafic layered intrusions of the Emeishan Large Igneous Province, SW China. Ore Geol. Rev. 65, 853–871 (2015).

Zhao, L. et al. Magnetite geochemistry of the Heijianshan Fe-Cu (-Au) deposit in Eastern Tianshan: Metallogenic implications for submarine volcanic-hosted Fe-Cu deposits in NW China. Ore Geol. Rev. 100, 422–440 (2018).

Araujó, J. C. S. & Lobato, L. M. Depositional model for banded iron formation host to gold in the Archean Rio das Velhas greenstone belt, Brazil, based on geochemistry and LA-ICP-MS magnetite analyses. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 94, 102205 (2019).

Huang, X. & Beaudoin, G. Textures and chemical compositions of magnetite from iron oxide copper-gold (IOCG) and Kiruna-type iron oxide–apatite (IOA) deposits and their implications for ore genesis and magnetite classification schemes. Econ. Geol. 114, 1–74 (2019).

Huang, X., Sappin, A. A., Boutroy, E., Beaudoin, G. & Makvandi, S. Trace element composition of igneous and hydrothermal magnetite from porphyry deposits: Relationship to deposit subtypes and magmatic affinity. Econ. Geol. 114, 917–952 (2019).

Dare, S. A., Barnes, S.-J. & Beaudoin, G. Did the massive magnetite “lava flows” of El Laco (Chile) form by magmatic or hydrothermal processes? New constraints from magnetite composition by LA-ICP-MS. Miner. Deposita 50, 607–617 (2015).

Knipping, J. L. et al. In-situ iron isotope analyses reveal igneous and magmatic-hydrothermal growth of magnetite at the Los Colorados Kiruna-type iron oxide–apatite deposit, Chile. Am. Mineral. 104, 471–484 (2019).

Bilenker, L. D. et al. Fe–O stable isotope pairs elucidate a high-temperature origin of Chilean iron oxide–apatite deposits. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 177, 94–104 (2016).

Broughm, S. G., Hanchar, J. M., Tornos, F., Westhues, A. & Attersley, S. Mineral chemistry of magnetite from magnetite-apatite mineralization and their host rocks: Examples from Kiruna, Sweden, and El Laco, Chile. Miner. Deposita 52, 223–244 (2017).

Ovalle, J. T. et al. Formation of massive iron deposits linked to explosive volcanic eruptions. Sci. Rep. 8, 14855 (2018).

Rojas, P. New contributions to the understanding of Kiruna-type iron oxide–apatite deposits revealed by magnetite ore and gangue mineral geochemistry at the El Romeral deposit, Chile. Ore Geol. Rev. 93, 413–435 (2018).

Troll, V. R. et al. Global Fe–O isotope correlation reveals magmatic origin of Kiruna-type apatite-iron-oxide ores. Nat. Commun. 10, 1712 (2019).

Childress, T. et al. Triple oxygen, hydrogen, and iron stable isotope signatures indicate a silicate magma source and magmatic-hydrothermal genesis for magnetite orebodies at El Laco, Chile. Econ. Geol. 115, 1519–1536 (2020).

La Cruz, N. L. et al. The geochemistry of magnetite and apatite from the El Laco iron oxide–apatite deposit, Chile: Implications for ore genesis. Econ. Geol. 115, 1461–1491 (2020).

Palma, G., Barra, F., Reich, M., Simon, A. C. & Romero, R. A review of magnetite geochemistry of Chilean iron oxide–apatite (IOA) deposits and its implications for ore-forming processes. Ore Geol. Rev. 126, 103748 (2020).

Rodríguez-Mustafa, M. A. A continuum from iron oxide copper-gold to iron oxide–apatite deposits: Evidence from Fe and O stable isotopes and trace element chemistry of magnetite. Econ. Geol. 115, 1443–1459 (2020).

Salazar, E. et al. Trace element geochemistry of magnetite from the Cerro Negro Norte iron oxide−apatite deposit, northern Chile. Miner. Deposita 55, 409–428 (2020).

Tornos, F., Velasco, F. & Hanchar, J. M. Iron-rich melts, magmatic magnetite and superheated hydrothermal systems: The El Laco deposit, Chile. Geology 44, 427 (2016).

Mungall, J. E., Long, K., Brenan, J. M., Smythe, D. & Naslund, H. R. Immiscible shoshonitic and Fe-P-oxide melts preserved in unconsolidated tephra at El Laco volcano, Chile. Geology 46, 255–258 (2018).

Lledo, H. L., Naslund, H. R. & Jenkins, D. M. Experiments on phosphate–silicate liquid immiscibility with potential links to iron oxide apatite and nelsonite deposits. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 175, 111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00410-020-01751-8 (2020).

Bain, W. M. et al. A fundamental role of carbonate–sulfate melts in the formation of iron oxide–apatite deposits. Nat. Geosci. 13, 751–757 (2020).

Bain, W. M. et al. Evidence for iron-rich sulfate melt during magnetite(-apatite) mineralization at El Laco, Chile. Geology https://doi.org/10.1130/G48861.1 (2021).

Rhodes, A.L., Oreskes N. Oxygen isotope composition of magnetite deposits at El Laco, Chile: Evidence of formation from isotopically heavy fluids. in Geology and Ore Deposits of the Central Andes. (Skinner, B.J. Ed.). Vol. 7. 333–351 (SEG Special Publication, 1999).

Sillitoe, R. & Burrows, D. New field evidence bearing on the origin of the El Laco magnetite deposit, northern Chile. Econ. Geol. 97, 1101–1109 (2002).

Pollard, P. J. An intrusion-related origin for Cu-Au mineralization in iron oxide-copper-gold (IOCG) provinces. Mineral. Deposita 41, 179–187 (2006).

Simon, A. C. et al. Kiruna-type iron oxide–apatite (IOA) and iron oxide copper-gold (IOCG) deposits formed by a combination of igneous and magmatic-hydrothermal processes: Evidence from the Chilean Iron Belt. SEG Sp. Pub. 21, 89–114 (2018).

Xie, Q. H. et al. Magnesium isotopic composition of continental arc andesites and the implications: A case study from the El Laco volcanic complex, Chile. Lithos 318–319, 91–103 (2018).

Sheets, S. A., Oreskes, N., Rhodes, A. L., Bodnar, R. J. & Szabo, C. Fluid inclusion evidence for a hydrothermal origin for magnetite-apatite mineralization at El Laco, Chile. Geol. Soc. Am. Abstr. Programs 2, A50 (1997).

Broman, C., Nyström, J. O., Henríquez, F. & Elfman, M. Fluid inclusions in magnetite-apatite ore from a cooling magmatic system at El Laco, Chile. GFF 121, 253–267 (1999).

Marschik, R. & Fontboté, L. The Candelaria-Punta del Cobre iron oxide Cu-Au (-Zn-Ag) deposits, Chile. Econ. Geol. 96, 1799–1826 (2001).

Velasco, F. & Tornos, F. Origen de las Pegmatitas de Magnetita-Apatito de la Mina Carmen del Fierro (Atacama, Chile). Macla No. 11 Septiembre 2009. (Revista de la Sociedad Española de Mineralogía, 2009).

Canil, D. & Lacourse, T. Geothermometry using minor and trace elements in igneous and hydrothermal magnetite. Chem. Geol. 541, 119576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2020.119576 (2020).

Deditius, A. P. et al. Nanogeochemistry of hydrothermal magnetite. Contrib. Miner. Petrol. 173, 46 (2018).

Palma, G. et al. Halogens, trace element concentrations, and Sr-Nd isotopes in apatite from iron oxide–apatite (IOA) deposits in the Chilean iron belt: Evidence for magmatic and hydrothermal stages of mineralization. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 246, 515–540 (2019).

Nadoll, P. Geochemistry of magnetite from hydrothermal ore deposits and host rocks—Case studies from the Proterozoic Belt Supergroup, Cu-Mo-porphyry + skarn and Climax-Mo deposits in the western United States. Ph. D. Thesis, University of Auckland (2011).

Wen, G. et al. Hydrothermal reequilibration of igneous magnetite in altered granitic plutons and its implications for magnetite classification schemes: Insights from the Handan-Xingtai iron district, North China Craton. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 213, 255–270 (2017).

Jonsson, E. et al. Magmatic origin of giant ‘Kiruna-type’ apatite-iron-oxide ores in Central Sweden. Sci. Rep. 3, 1644 (2013).

Childress, T., Simon, A. C., Day, W. C., Lundstrom, C. C. & Bindeman, I. Iron and oxygen isotope signatures of the Pea Ridge and Pilot Knob magnetite-apatite deposits, southeast Missouri, USA. Econ. Geol. 111, 2033–2044 (2016).

Westhues, A. et al. Tracing the fluid evolution of the Kiruna iron oxide apatite deposits using zircon, monazite, and whole rock trace elements and isotopic studies. Chem. Geol. 466, 303–322 (2017).

Hurwitz, S. & Navon, O. Bubble nucleation in rhyolitic melts: Experiments at high pressure, temperature, and water content. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 122, 267–280 (1994).

Edmonds, M., Brett, A., Herd, R. A., Humphreys, M. C. S. & Woods, A. Magnetite-bubble aggregates mixing interfaces in andesite magma bodies. Geol. Soc. Lond. Sp. Pub. 410, 95–121 (2014).

Knipping, J. L., Webster, J. D., Simon, A. C. & Holtz, F. Accumulation of magnetite by flotation on bubbles during decompression of silicate magma. Sci. Rep. 9, 3852 (2019).

Simon, A. C., Pettke, T., Candela, P. A., Piccoli, P. M. & Heinrich, C. A. Magnetite solubility and iron transport in magmatic-hydrothermal environments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68, 4905–4914 (2004).

Barton, M. D. Iron oxide (-Cu-Au-REE-P-Ag-U-Co) systems. in Treatise on Geochemistry, 2nd edn. 13. (Elsevier Ltd., 2013).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by ANID through Millennium Science Initiative Program (NCN13_065) and FONDECYT grant # 1190105. Additional support was provided by ANID-FONDAP project 15090013 “Centro de Excelencia en Geotermia de Los Andes, CEGA”. We would like to thank editor Mark Kendrick for handling the manuscript, and reviewers Carlos Spier and Tong Hou for their constructive and helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.P., M.R. and F.B. conceived and designed the study, and wrote the paper. Magnetite thermometry and compositional data analysis was carried out by G.P. with help from J.T.O., under the supervision of M.R. All the authors analysed and discussed the data, and revised and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Palma, G., Reich, M., Barra, F. et al. Thermal evolution of Andean iron oxide–apatite (IOA) deposits as revealed by magnetite thermometry. Sci Rep 11, 18424 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97883-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97883-3

This article is cited by

-

Formation of iron oxide–apatite deposits

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.