Abstract

As nations agreed on a bottom-up approach to establish the Paris Agreement in 2015, Non-state Actors (NSAs) became increasingly acknowledged as key players in the implementation of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). In a mostly urbanised world, local governments have a major part to play in designing and implementing climate policies that will help overcome carbon lock-in and enable the transition to a sustainable low-carbon future. Transnational municipal networks (TMNs) have a well-documented history of contributing to multilevel climate governance and supporting experiments in local climate action in many countries. In Brazil, urban climate experimentation has increased since 2005 and accelerated after 2015. Based on empirical evidence from a national survey and two Brazilian metropolises, the study demonstrates that TMNs have been drivers of the municipal climate agenda in Brazil, but there is no evidence so far that urban governance experiments have resulted in significant greenhouse gas emission reductions. Furthermore, the collective impact of cities' experimentation on the national climate agenda is yet to be verified. In light of multilevel climate governance and the urban experimentation conceptual framework, we contend that while there is no documented evidence that local climate action has affected Brazil's ability to meet its mitigation goals, cities' paradiplomacy and policy experiments have strengthened a multilevel approach to climate governance and contributed to positive change towards a sustainable transition. Furthermore, a closer look at policies across scales and their interactions will help our understanding of how to improve t'he institutional framework for climate governance in Brazil and secure GHG emission reductions, thus contributing to global goals beyond 2020.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To address the most challenging collective action problem in modern era, nations have moved from a top-down binary approach that resulted in the Kyoto Protocol in 1998, to a bottom-up process that culminated in the 2015 Paris Agreement (UNFCCC, 2015; Brun, 2016, p. 115). The treaty provides a decentralised framework that allows parties to establish their own reduction targets and to revise them according to their capacity and political demands (Keohane and Oppenheimer, 2016, p. 150). In light of the Kyoto Protocol´s failure to engage parties in a binding commitment, the Paris Agreement shifts responsibility from international negotiations to domestic action. Non-state actors (NSAs), and particularly subnational governments will thus contribute towards transitioning to a low carbon economy.

Notwithstanding positive developments since 2005Footnote 1, nations have made little progress in reducing fossil fuel dependency; it now seems unlikely that nations will reach the goal established by the Paris Agreement, to keep global temperature rise below 2 °C in this century (UNEP, 2017). The climate regime became increasingly complex, and the demand for a polycentric and multilevel approach to global climate governance is recognised by scientists and decisionmakers (Keohane and Victor, 2009; Abbott, 2012; Biermann and Pattberg, 2012; Bulkeley et al., 2012; Bäckstrand et al., 2017). NSAs had participated as observer groups since the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) entered into force and became acknowledged key players with a central role in the Paris Agreement implementation. Their actions are reported within the international governance framework through the NAZCAFootnote 2 platform established in 2014 by the UNFCCC. By June 2018, NSAs including business, civil society organisations and subnational governments had reported over 12,500 climate actionsFootnote 3 cities alone accounted for over 2500 entries, including from BrazilFootnote 4.

This article is divided into four sections:

The first section addresses the politics of climate change, outlines the theoretical framework and describes methodological aspects of the research underpinning this article. It frames urban climate action within a multilevel perspective in dialogue with transition theory as experiments leading to changes in carbon dependent paths. This section includes a list of acronyms and abbreviations in Box 1.

Section two assesses the municipal climate agenda in Brazil vis-à-vis the national context in the period from 2005 to 2018, highlighting action after 2015. It analyses data from surveys and reports from desk-based research, and cross-references results using semi-structured interviews conducted with selected stakeholders by the main author. The cases of Belo Horizonte and São Paulo provide further empirical evidence on policies conceptualised as urban governance experimentationFootnote 5.

Section three discusses the role of Transnational Municipal Networks (TMNs) as drivers of the municipal climate agenda in Brazil, besides the effectiveness and impact of governance experiments on domestic climate governance. The article ends with concluding remarks on these experiments in the given timeframe, their potential outcomes and insights into the way forward. By exploring the linkages between TMNs and Brazilian cities´ climate experimentation, we hope to shed light on the municipal climate agenda of the South, thus contributing to the research on urban climate action and multilevel governance (Acuto et al., 2018).

Theoretical framework and methodological aspects

This article is guided by three theoretical strands to understand how Brazilian cities participate in global climate governance. First, it discusses global climate governance and the interplay between world politics and transnational relations at a sub-state level; second, it assesses agency and authority of subnational players in global climate governance, leveraged by transnational cooperation; third, it analyses urban climate governance experiments in light of sustainability transitions vis-à-vis domestic climate governance. A list of acronyms and abbreviations can be found in Box 1.

The paper adopts the analytical meaning of governance within the International Relations (IR) discipline as an observable phenomenon, notwithstanding intersections with the normative approach, as described by authors Dingwerth and Pattberg (2006:198; p. 189–203). It also considers the political dimension applied by practitioners that captures the interplay between world politics and transnational relations—or paradiplomacy—of municipal governments.

Based on empirical evidence, the paper further examines the effects of transnational activities carried out by cities on domestic climate governance. Assessing agency and authority of Brazilian cities in designing and implementing climate governance policies is drawn from self-declared climate action; specifically, from a sample of 752 municipalities that responded to an online survey on environmental management between September 2015 and March 2018 (Anamma, 2018) and the subset of 27 capital cities.

In the intersection between polycentricity, multilevel and transnational climate governance and urban climate experimentation, the paper scrutinises the cases of Belo Horizonte and São Paulo in the period from 2005 to 2018. These exemplary cases support analyses to verify their participation in global climate governance.

Polycentricity and multilevel climate governance

Nobel prize winner Elinor Ostrom called for the need to evolve from a global state-centric towards a polycentric approach to climate governance, borrowing from theoretical work on collective action problems in urban areas. “It is important that we recognise that devising policies related to complex environmental processes is a grand challenge and that reliance on one scale to solve these problems is naïve.” (Ostrom, 2009, p. 28). Betsill and Bulkeley (2006, p. 142) frame the role of cities in global climate governance within a multilevel, multi-scalar perspective, to grasp the complexities of relations between multiple actors and the social, political and economic processes involved therein. The Multilevel Governance (MLG) concept was originally developed to reflect on the political processes in the European Union (Piattoni, 2010), and has since been widely adopted by scholars to understand the role of subnational actors in global climate policy-making. MLG involves national and international relations, vertical and horizontal, formal and informal interactions, thus challenging conventional boundaries and distinctions between local, national and global politics (Bulkeley and Betsill, 2005). To sum up, the MLG theory analyses of the many levels and spheres of authority, shared and overlapping competencies, and various new forms of governance arrangements that characterise climate governance.

The Brazilian cases presented here can be viewed from the polycentric perspective on governance since the authority and power to act are decentralised, according to the country´s federative structure determined by the 1988 Constitution. However, local governments in Brazil act in a nested institutional and legal environment, subordinate to central government; despite the decentralised institutional framework guaranteed by the Constitution, power and resources are concentrated at federal level, therefore, analyses require a multifaceted and more encompassing approach (Morrison et al., 2017; Bernstein and Hoffmann, 2018); the MLG framework provides such an approach.

The article´s underlying assumptions are that world politics based on a state-centric framework will continue to prevail in the next decades and that sub-state diplomacy occurs in a cooperative environment to attain global climate goals; the authority of states is recognised, and although other players increase their authority and leadership, nations still have the leading role in the global climate polity. Research on Brazilian cases corroborates findings from international studies regarding the interdependent relational nature of climate governance (see Matschoss and Repo, 2018; Hickmann, 2016; Johnson et al. 2015). Thus, to be effective, subnational governments´ self-governing initiatives “require maintenance of a rule-based framework negotiated by nation-states in multilateral settings” (Hickmann, 2016, p. 297).

The literature on global climate governance further evolved to assess the role of subnational governments and networks, how they operate and what determines their engagement (Bansard et al., 2017; Kern and Alber, 2009). We refer to such activities as paradiplomacy; there is some controversy about the term´s adequacy to describe transnational interactions between subnational governments (Duchacek, 1984), since it might be interpreted as a lesser form of diplomacy (Kinkaid, apud Setzer, 2013, p. 40). Nonetheless, it has been widely used interchangeably with terms such as federative diplomacy, constituent diplomacy and city diplomacy (see Pluijn, 2007; Setzer, 2013). This article analyses paradiplomacy in Brazil considering municipalities as federated units, emphasising the cooperative rather than the conflictive relation with the state, adopting Cornago´s concept that defines paradiplomacy as:

“[…] sub-state governments’ involvement in international relations, through the establishment of formal and informal contacts, either permanent or ad hoc, with foreign public or private entities, with the aim to promote socio-economic, cultural or political issues, as well as any other foreign dimension of their own constitutional competences” (apud Setzer, 2013, p. 41)

While some scholars have scrutinised the major city networks demonstrating their agency through collective action (Betsill and Bulkeley, 2004, 2006, 2007; Gordon and Acuto, 2015; Hickmann, 2016), others explore their role in global climate politics and governance (Toly, 2008; Biermann and Pattberg, 2012; Acuto and Rayner, 2016; Bansard et al., 2017). Yet another group examines how transnational cooperation networks of cities empower local governments worldwide through knowledge and practice sharing (Bulkeley and Betsill, 2005; Betsill and Bulkeley, 2007; Andonova et al., 2009; Corfee-Morlot et al., 2009; Fischer et al., 2015; Gordon and Acuto, 2015; Hickmann, 2016). However, in most studies, empirical evidence derives from cases in the global North. Less attention has been given to the vertical interactions between developing countries´ subnational policies, and domestic and global climate governance (Biderman, 2011; Castán-Broto and Bulkeley, 2013; Somanathan et al., 2014; Setzer et al., 2015, Macedo et al., 2016). Notwithstanding the limitations of transferring experiences between developed and developing countries´ cities, lessons can be learned from such cases. One reason is that, in a globalised economy, urban societies North and South share consumption patterns and a development model which is strongly dependent on fossil fuels. Moreover, urban growth is forecast to accelerate in the South until 2030. Thus, understanding urban climate governance experiments in the South can help improve effectiveness of domestic policies to meet global ambitions.

Authority and agency of subnational players

Literature on global climate governance has identified a reconfiguration of authority from central governments to NSAs and across multiple levels of decision-making, challenging classical approaches to studies in international relations (Hickmann, 2016, p. 52). It has been widely discussed that in contemporary configurations of global environmental politics, authoritative power to set rules, norms and standards has shifted from state-centric to multilevel and hybrid spheres of decision-making regarding responses to climate change (see Hickmann et al., 2017). This does not undermine state authority, but rather subnational and non-state actors still operate in a rule-based framework negotiated by nations, as argued by Hickmann (2016). In fact, an investigation carried out by Andonova et al., (2014) finds that country-level factors are the main drivers for subnational participation in transnational climate governance. Fischer et al., (2015) assess the cities´ perspective on global environmental issues, while highlighting their relevance in international relations, and contend that “[…] it is imperative to think of the city’s role as a sphere of governance nested within but mostly subordinate to other realms of politics […]” (2015, p. 9). Thus, scholars on climate governance overall agree that tackling the global climate challenge demands cooperation beyond geographical and jurisdictional boundaries, notwithstanding their different roles and powers.

In Brazil, climate change science and policy have been the subject of interdisciplinary investigation encompassing fields such as geography, economics, law, social sciences and public health (PBMC, 2014). IR as a discipline has gained traction since the early 2000s, and climate governance is now a burgeoning field for research, albeit with a primary focus on national level policies (see Vigevani, 2006; Viola et al., 2013; Inoue, 2016; Mauad et al., 2017). Academic work on cities and climate change is incipient and has so far concentrated on describing specific cases, with some regard to paradiplomacy and transnational networks (Koehntopp, 2010; Puppim de Oliveira, 2009; Barbi, 2014; Mauad et al., 2013; Silva and Rei, 2014; Ramires, 2015). The nexus between TMNs and Brazilian cities´ participation in transnational and multilevel climate governance is still underexplored (Setzer et al., 2015; Macedo, 2017).

Urban climate experimentation

Another angle for conceptualising urban climate action lies in experimentation and transition theory; it assumes that urban experiments can leverage transitional visions, strategies and actions (Caprotti and Cowley, 2016). Although some scholars raise the question about the effectiveness of such initiatives to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and consumption in cities (Johnson et al., 2015), a wider scope of analysis can identify linkages between urban governance experiments and sustainability co-benefits (see Puppim de Oliveira et al., 2013).

This article examines selected urban climate governance experiments in Brazil, understood as initiatives that involve innovation and learning, outside the state-based multilateral treaty (Castán-Broto and Bulkeley, 2013). Interventions based on new institutional arrangements at the local level are expected to lay the foundation for sustainability transitions that will ultimately affect human societies worldwide. They occur in a context of resistance to change, identified as lock-in:

“[…] the inertia of technologies, institutions, and behaviours [that] individually and interactively limit the rate of such systemic transformation by a path-dependent process known as carbon lock-in, whereby initial conditions, increasing economic returns to scale, and social and individual dynamics act to inhibit innovation and competitiveness of low-carbon alternatives” (Seto et al., 2016, 19.2).

We examined policy innovation in Belo Horizonte and in São Paulo according to Bernstein and Hoffman´s definition of experimental climate governance as “an initiative that seeks to disrupt carbon lock-in in a specific target through intentional attempts to authoritatively steer actors.” (2018, p. 9), assessing the different outcomes in each case.

Many IR and political science studies on climate governance have scrutinised the São Paulo case, but fewer have investigated climate action in Belo Horizonte. Our assessment of Belo Horizonte hinges on its history in paradiplomatic activities and environmental leadership. Besides typology differences, it contrasts with São Paulo in terms of policy continuity, outcomes and political engagement.

São Paulo first grasped the attention of climate governance scholarship in 2009, when the Executive submitted a bill on climate change policy to the City Council. The Legislative body voted unanimously to pass it, and it became law no. 14.933 (Setzer, 2009; Biderman, 2011; Back, 2012; Ramires, 2015). However, analyses in Brazil of its development and implementation have not framed it as an urban climate experiment, despite the fact that many international scholars have scrutinised such policies under the experimentation lens when researching multiple experiences worldwide. Governance experimentation has been scarcely investigated in the South, specifically not in Latin America and Brazil (See Heijden, 2018, Castán-Broto and Bulkeley, 2013; Di Giulio et al., 2017). The implementation of São Paulo´s climate law is still uncertain. On the other hand, Belo Horizonte embraced the climate agenda, and has endeavoured to internalise mitigation and adaptation in environmental urban governance.

We claim that experiments driven by transnational engagement have internalised the global climate challenge and affected the municipal agenda by spurring further experimentation in different departments and other cities. They have also affected policies, at state and national levels throughout the country thereby creating critical mass to support coordinated multilevel and multi-scalar climate actions (Biderman, 2011; Setzer, 2013; Hickmann et al., 2017).

The article further evaluates Brazilian municipalities´ engagement in climate governance vis-à-vis national commitments in the Paris Agreement (NDCs). It aims to answer the following questions: How do municipal paradiplomatic activities and transnational network engagement impact the national climate agenda in Brazil? Under what circumstances can urban governance experiments driven by transnational engagement effectively contribute to the implementation of Brazil´s objectives in the NDCs?

Methodology

Empirical evidence underpinning this investigation was obtained from the following sources:

-

1.

ANAMMA (National Association of Municipalities and Environment): an online national survey, launched in September 2015 that was still ongoing at the time of writing of this paper. By March 2018, it had received input on environmental policies and management from 752 municipal environmental agencies, including from 8 capital cities.

-

2.

Platforms (NAZCA, cCR, CDP, CB27Footnote 6), transnational and national cities networks´ reports and municipal online databases. Reports on self-declared actions provided details allowing more in-depth analyses of the municipal climate agenda in Brazil and the TMN-climate experiment nexus.

-

3.

Semi-structured interviews with elite stakeholders. In-person interviews were conducted from January to May 2017 by the leading author within her doctoral research. Interviewees included 31 representatives from municipalities, TNMs and National Municipal Associations (NMAs), as well as federal government senior staff, academia, Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), and one international foundation (Table 1).

The questions focused on understanding cities´ paradiplomacy, how they have integrated global climate concerns in their agendas, and how these activities affected interactions between national and municipal governments to develop and implement mitigation strategies. The interviewees were also asked about their perceptions on the contributions from Brazilian cities to TMNs and global climate governance.

The research then honed in on climate governance experiments in Belo Horizonte and São Paulo, two metropolises in the more developed South-East region of Brazil. In line with Jordan and Huitema´s analytical perspective on policy innovation (2014, p. 24), the chosen municipalities undertook the “societal problem solving or change experiments” by establishing novel governance and institutional arrangements involving public participation and a shared vision.

The following premises underlie this choice:

-

They are representative of Brazil´s metropolises in terms of demographics, economy and consumption patterns. Belo Horizonte is a benchmark for socioenvironmental initiatives; São Paulo is a global city, a beacon for innovative urban governance and the third largest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the country.

-

Transport comprises the largest source of GHG emissions in both cities, as in most capital cities in Brazil; São Paulo´s vehicle fleet alone accounts for 13% of the national car fleet in in 2017Footnote 7.

-

Both capitals have a robust legal and institutional framework for climate action. They reported GHG emissions and qualitative information in their own websites, TMNs´ websites and publications, and international platforms.

-

They have been actively engaged in environmental paradiplomacy and transnational climate governance through TMN; they are signatories of the Compact of Mayors (CoM)Footnote 8.

Climate governance and local action in Brazil

Brazil is an emerging economy with a population of over 200 million inhabitants, of which 84 percent live in cities. It is also among the ten largest GHG emitters, responsible for 3.4 percent of total global emissions in 2016 (Brazil, 2017; OC, 2017). Agriculture, land use change and forestry together account for 73 percent of Brazil´s GHG emissions. Nonetheless, energy emissions, notably from the transport sector have been increasing rapidly since 2010 (OC, 2018). There is no indication that there will be any significant shift from a fossil-fuel based transport model in the coming decades, since Brazil´s mitigation policies prioritise land use change and deforestation reduction (See Fig. 1).

Brazil has been an acknowledged player in global environmental governance since 1992. Its diplomacy took the lead on many occasions, as in the negotiations that led to the Kyoto Protocol (La Rovere et al., 2002). Nevertheless, its engagement in the climate arena has been strongly oriented by the UNFCCC´s principle of common but differentiated responsibilities that in a way, limited mitigation efforts in Brazil (Mauad et al., 2017). In December 2009, during the Fifteenth Conference of the Parties (COP15) in CopenhagenFootnote 9, Brazil submitted voluntary reduction goals. The target, ranging from 36 to 39 percent of GHG emissions relative to its projection for 2020, is established in the National Climate Change Policy Law (Política Nacional de Mudança do Clima, Law n. 12187, henceforth PNMC).

Following negotiations that led to the Paris Agreement, Brazil submitted its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) to the UNFCCC Secretariat in September 2015, declaring absolute GHG emission reduction goals of 37 percent by 2025 and 43 percent by 2030, relative to 2005 levels (Brazil, 2015). So far, Brazil is on track to meet its 2020 targets, mainly by addressing deforestation and sustainable agriculture (OC, 2018; Speranza et al., 2017). In 2015, total emissions were 35 percent less than estimated by government scenarios, mostly due to dramatic reductions in deforestation rates (OC, 2018)Footnote 10.

In its NDC, Brazil pledged to reduce its GHG emissions by 37 percent in 2025, and 43 percent in 2030, relative to 2005 levels. Unlike the target set in the PNMC, these refer to absolute levels, not projections, limiting emissions to 1300 and 1200 MtCO2eq in 2025 and 2030, respectively. Although CSOs consider these to be modest ambitions, it is not guaranteed that the NDC will be reached. Furthermore, prospects after the 2018 presidential elections are not optimistic: the new administration beginning in January 2019 gives no indication that it will even consider the climate agenda, as its priorities are economic growth, as well as combatting corruption and violence. These commitments have nationwide economic and social implications for urban populations, given their increasing demand for agricultural products such as beef and soy, as well as timber for constructionFootnote 11.

Besides specific climate ruling, government has established other regulatory instruments consonant with the PNMC and relevant to the urban climate change agenda, such as the 2010 National Law on Solid Waste Management (PNRS) and the National Policy on Urban Mobility of 2012 (PNMU). A review of climate related legal and institutional framework in Brazil indicates that if implemented, policies would lead to significant GHG emission reductions, despite the need for adjustments (IES-Brasil and FBMC, 2016; OC, 2017, 2018). For instance, the PNMU is far from attaining its objectives that have an impact on transport´s emissionsFootnote 12. Furthermore, federal incentives for the oil and vehicle industries (2008–2017) have offset municipal efforts to reduce these emissions (Setzer et al. 2015; Macedo, 2017), and prospects for the next decade are that the national government will continue to prioritise investments in the fossil fuel-based economyFootnote 13.

Climate paradiplomacy challenges

Brazil´s federative system regulated by the 1988 Constitution is a challenge for integrating municipalities in national and global climate governance (Vigevani, 2006). Although Brazil acknowledges the autonomy of its federated units, international affairs remain the exclusive competency of the national sphere of government. Environmental protection, however, is shared by the three levels of government. Municipal and state governments have been engaging in environmental paradiplomacy since the 1990s but without a clear regulatory framework (Aprigio, 2016). Subnational authority to act internationally is contingent on leadership´s political influence and institutional and financial capacity vis-à-vis the country (Farias, 2015, p. 126). Some authors argue that subnational players can be considered agents in international law in light of modern jurisprudence (Granziera and Rei, 2015; Setzer et al., 2015). Other scholars adopting the traditional IR approach frame the issue within foreign policy analysis, and identify boundaries to subnational diplomacy in Brazil (Salomon, 2011, p. 47). This is the view of many diplomats and negotiators. A senior official and climate negotiator stated:

“For me, paradiplomacy means an ideologically motivated contact occurring directly between political parties and other countries´ revolutionary movements, outside official channels for obvious reasons. It should not be confused with subnational governments´ cooperation in transnational networks. States and cities are [an integral] part of the Brazilian State […]. This is not “para” diplomacy, it is part of diplomacy […] Federal Diplomacy is a more adequate definition.” Footnote 14

Federal government, therefore, provided moderate support to sub-state players´ engagement in climate paradiplomacy, albeit more intensely after 2015. For instance, municipal authorities and technical staff have participated in the national delegation at COPs since 2001. They also attended informal preparatory meetings with other NSAs, held by the International Relations Ministry (Ministério das Relações Exteriores, henceforth MRE) since 2009. But far from the debate on authority to act in foreign affairs, municipal governments are more concerned with accessing finance to implement locally relevant policies, such as sustainable waste management or clean transport, that also impact climate governance. This has been the main motivation behind local leaders´ decision to join climate initiatives, as stated by many policymakers and officials (Macedo, 2017, p. 135–140). Nonetheless, as acknowledged by most interviewees, Brazilian cities´ participation in TMNs has helped strengthen the voice of subnational governments domestically, while increasing their collective agency in the international climate arena.

Mapping local climate action

Until the early 2000s, knowledge about climate change was confined to academia and federal government agents involved in international negotiations; very few Brazilian cities were familiar with the issue (Macedo, 2017). Their engagement in the climate agenda can be correlated with earlier transnational cooperation´ activities; for instance, TMNs recruited local governments and environmental Non-governmental Organisations (NGOs) to participate in projects funded by multi and bilateral agencies, to implement Rio 92 agreements (Almeida et al., 2013; Marcovitch and Dallari, 2014). Socio-technical experiments have become well known as successful cases of urban interventions having an impact on climate change; for instance, solar water heating in social housing in Belo Horizonte, Curitiba’s Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system, recycling cooperatives in Porto Alegre and the cycle routes in Rio de Janeiro, which were set up throughout the 1990s, and even earlier in the case of Curitiba´s BRT.

Rio de Janeiro was the first municipal government in Brazil to develop a GHG emissions inventory in 1998, motivated by its adhesion to ICLEI and the international Cities for Climate Protection (CCP) campaignFootnote 15. Further evidence on municipal climate paradiplomacy can be traced back to June 2002, when ICLEI launched the CCP campaign in South America, funded by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). Initially, CCP involved 7 Brazilian cities, and was extended until June 2005, following the Kyoto Protocol´s ratification. Participants committed to implementing the five-milestone methodology, which included a baseline GHG emissions inventory; a reduction target; a local action plan; implementing mitigation measures; monitoring implementation and reviewing the plan.Footnote 16

Between 2005 and 2010, municipal climate activities increased, mostly through participation in theme projects developed by international agents functioning as facilitators, including NGOs; ICLEI and C40 directly engaged key cities in the climate agenda after 2005, funded by international or bilateral cooperation agencies. These players, also defined as orchestrators (Abbott et al., 2015) have a determining role in soft governance: they enable climate action through programmes and projects addressing the urban agenda within the international cooperation framework, involving developed countries´ funding mechanisms and implementers. However, the impacts of these experiments were only assessed throughout their validity period. There is no track record in the medium/long-term.

Climate programmes and projects typically address specific issues on the urban agenda, such as renewable energy, waste management, green building or sustainable transport, and engage selected cities. Belo Horizonte, Curitiba, Porto Alegre, Rio de Janeiro and São PauloFootnote 17 actively engage in climate projects and often participate simultaneously in several initiatives. These capitals are concentrated in the more developed South-East/South regions, but after 2015, cities throughout the country have also joined, becoming nodes of polycentric climate governance (Heidjen, 2018). Evidence of this process is found in the CB27 and TMN reports, as well as in the survey detailed below.

The CCP was the pioneer and most effective international climate initiative in Brazil. Others that followed include the C40 (2005), CDPCities (2011) and the 100 Resilient Cities (100RC, 2013). Until 2016, Brazilian municipal associations were more concerned with a domestic agenda focusing predominantly on urban management and financing (CNM, 2008). TMNs member cities are also members of NMAs, mostly as leaders, and have helped place climate change on the municipal agenda in Brazil, as acknowledged by interviewees in this research. These trailblazers have engaged in experimentation and inspired other leaders to innovate by framing urban management issues as climate initiatives. Cities´ participation in global multilevel climate governance is represented by the diagram in Fig. 2.

The ANAMMA survey

In September 2015, the national association of municipal environmental authorities (ANAMMA) launched an online survey named “environmental census” (CENSO ambientalFootnote 18), to determine the state-of-play of municipal environmental management including policies, institutional architecture and budget. The survey contains one question on climate change whereby respondents are required to identify their city´s climate-related initiatives among several actions involving outreach, mitigation, resilience and adaptation and governanceFootnote 19.

By March 2018, there was feedback from 752 municipalities (including 8 capital cities)Footnote 20, equivalent to 13.5 percent of the total 5570 municipalities in Brazil.Footnote 21 In April 2017, there had been 433 respondents, or 8 percent of the total. Table 2 compares data in this one-year period to illustrate the overall increase in local climate action throughout the country. It summarises the compiled results on local climate action, systematised according to the scale (in number of inhabitants) of participating cities informed by identified municipal representatives. Albeit not providing details on activities, there is clear indication that awareness about the correlation between climate and municipal issues increased significantly regardless of the city's size. This survey has the potential to leverage further in-depth research on urban climate innovation and experiments beyond the “usual suspects” (Heijden, 2018; Bulkeley and Castán-Broto 2013).

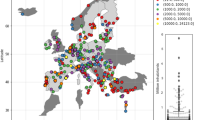

The survey ensued the one-year period of intense activity in transnational cooperation prior to COP21Footnote 22. A key indicator of increasing subnational climate action is their adhesion to international voluntary pledges, such as the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy (GCMCE). TMN engagement requires members to adopt self-determined targets and sign international pledges. In June 2018, there were 34 Brazilian CoM/GCMCE signatories, all but three being active NMAs and TMN members. (Figs 3 and 4). Although it is not possible yet to quantify or even determine whether these actions will lead to actual GHG emissions reductions, (Johnson et al., 2015), we can assume that with adequate support, such voluntary commitments could leverage experimentation and increase innovation (Abbot, 2016).

ANAMMA´s survey results in a one-year period suggest that this concerted effort driven by TMNs to insert climate change into the municipal agenda was successfulFootnote 23. We caution, however, that reported initiatives are self-declared; there is no evidence to determine their effectiveness so far.

The Brazilian forum of state capital cities´ environmental departments CB27

In June 2012, during the UN meeting in Rio de Janeiro, Rio + 20, environmental secretaries of the 27 capital citiesFootnote 24 gathered to establish the CB27. Inspired by the C40, it fosters sharing information on best practices, promotes peer-to-peer learning, and empowers municipal environmental leadership (Cerqueira and Vicente, 2016; CB27/Kas, 2017)Footnote 25 by strengthening their collective agency (Hickmann, 2016). The first CB27 report includes urban sustainability practices related to climate mitigation, such as methane capture from landfills, using clean fuels in the public transport fleet, implementing BRT systems, creating and expanding cycleways, metro and light rail transport systems (Knirsch, 2012). Despite not focusing explicitly on innovation, this forum has a significant role in disseminating urban climate experiments and promoting policies as beneficial for municipal management beyond environmental concerns.

CB27 members are economic regional hubs, including 13 metropolises with over one million inhabitants. Its political stake in Brazil has grown especially after COP21 and it is increasingly being recognised by the federal government as the cities´ voice on climate issues. Alongside TMNs, the CB27 has the resources to orchestrate a more scientific approach to promote innovation and systematic learning (Abott, 2017).

Eleven capital cities with GHG emission inventories and climate related policies are ICLEI members. Together they represent an estimated population of over 33.3 million inhabitants (IBGE, 2016). By March 2018, all capital cities (except one) had adhered to the GCMCE; fourteen had developed GHG inventories and nine had issued climate policiesFootnote 26. Six cities established emissions reduction targets, and eight had developed mitigation action plans (Anamma, 2018; Macedo, 2017). Annex 1 (Supplementary information) contains a table summarising the environmental profile, paradiplomacy and climate action of Brazilian capital cities.

After COP14 in Lima, and the intensified campaign led by TMNs to recruit signatories for the CoM/ GCMCE, many more municipalities engaged in climate action. By March 2018, the GCMCE listed 57 Brazilian cities, from 34 in the previous year.Footnote 27

Municipal governments in Brazil were empowered by TMNs in many ways as they became acknowledged stakeholders in the international arena, participating in shaping a global urban agenda and in setting ambitious mitigation goals sharing (Bulkeley and Betsill, 2005; Andonova et al., 2009; Gordon and Acuto, 2015; Hickmann, 2016). They gained access to resources, such as knowledge, technology and funding for environmental actions, and positioned themselves as environmental leaders vis-à-vis national government, as demonstrated by their often more ambitious voluntary GHG emission reduction targets (see Bouteligier, 2014; Setzer et al., 2015). Decision makers and senior staff acknowledge benefits from paradiplomatic engagement. In the words of an environmental official from Belo Horizonte “the city´s participation in TMNs resulted in positive outcomes [due to climate policies],such as a significant decrease of respiratory disease cases and losses due to flooding.”Footnote 28 Salvador´s municipal environment secretary considers that “participating in transnational networks is fundamental for inspiration and learning about what to do and how to avoid repeating mistakes.”Footnote 29 We argue that this focus on co-benefits does not affect potential mitigation results, as questioned by some researchers (Bansard et al., 2017). In fact, it adds consistency to a locally based approach to sustainability and carbon lock-in.

The establishment of CB27 and its diffusion role have helped to significantly broaden the scope of urban climate action in Brazil. After 2015, several capital cities´ mayors who were leaders of national networks helped disseminate information on climate change and their interventions throughout the country, further engaging other cities in experimenting with climate mitigation as learning opportunities (Castán-Broto and Bulkeley, 2013; Abbot, 2016). Considering that infrastructure such as roads, buildings and communications systems will be built in the urban environment in the coming decades, these are also opportunities to disrupt carbon lock-in, particularly within their jurisdiction (Caprotti and Cowley, 2016).

Climate governance experiments in Belo Horizonte and São Paulo

To better understand the extent of urban climate governance experiments in Brazil, we examined empirical evidence in more detail from two capital cities. These metropolises followed different paths in their paradiplomatic activities during the period covered by this research. While Belo Horizonte (BH) increased its activities, taking on a leadership role vis-à-vis TMNs in 2012, the city of São Paulo (CSP), after passing innovative climate legislation in 2009, distanced itself from climate paradiplomacy and the overall environmental agenda in 2013 (Macedo et al., 2016).

City of Belo Horizonte ( Prefeitura de Belo Horizonte – PBH) Footnote 30

The capital city of Minas Gerais state, Belo Horizonte (BH)| has been an ICLEI member since 1994. In 2005, the PBH established the international relations department, which acted together with the environment secretariat and the mayor´s office to engage in TMN climate activities, including the CCP campaign. In 2012, BH hosted ICLEI´s World Congress, held for the first time in Latin America.

BH established a municipal climate policy through Law N° 10.175 in 2011. The Committee on Climate Change and Ecoefficiency (CMMCE), created in 2006, oversees its implementation. It is a multistakeholder consultative body which coordinates and promotes debates on climate change between sectors of society. Until 2018, BH had conducted three municipal GHG emission inventories, and developed a climate action plan in 2014 (PBH, 2016a). The third revision of its GHG inventory adopted the Global Protocol for Community-Scale Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GPC, 2014) methodology, and the city reported its climate action in the Carbonn Climate Registry (cCR) and CDPCities platforms.

Belo Horizonte further integrated climate change in urban policies in 2015, by amending Organic Law n° 8/2015, that lays the ground for the new Master Plan passed by the City Council, establishing measures that affect climate related issues, such as incentives to non-motorised modes and efficient sustainable urban transport (PBH, 2016a). BH was the first city to launch a Vulnerability Assessment (PBH, 2016b). Therefore, it has followed a path that is consistent with the transition approach, building on its governance experiment that leveraged new sustainability policies and climate action (Matschoss and Repo, 2018; Kivimaa et al., 2017; Castán-Broto and Bulkeley, 2013).

Despite these efforts, the 2014 municipal GHG emission inventory showed that BH´s emissions had increased 70 percent in 2014 compared to the baseline year of 2000 (Fig. 5). The municipal GDP increased 47.9 percent in the same period, demonstrating a more carbon-intensive development in the city (PBH, 2015).

Given the scope and timeline of this research, it was not possible to determine if these experiments had affected the city´s emissions, and whether or not they would have further increased in the absence of these policies.

City of São Paulo (Prefeitura Municipal de São Paulo–PMSP)

São Paulo is a global city, and a recurring object of research on urban development and socioenvironmental problemsFootnote 31. It portrays the inequalities of a developing economy, and at the same time provides many innovation opportunities of a world class megacity in the South (Frug, 2011; Sudjic, 2011; Sassen, 1994; 2015).

The city suffers from chronic traffic congestion and air pollution, affecting quality of life and productivity. Thus, transport has been a priority for virtually every administration. Transport is also the city´s largest source of GHG emissions, accounting for 68.6 percent of the total in 2011 (Instituto Ekos and Geoklock, 2013). Amongst the several challenges in addressing urban mobility issues domestically, a fragmented governance framework, alongside investments in infrastructure oriented mostly towards road transport and passenger cars account for the lock-in at multiple levels that prevents implementing sustainable alternatives (Bernstein and Hoffmann, 2018).

In 1994, São Paulo was one of the first Brazilian cities to become an ICLEI member. In 2003, the PMSP introduced climate change issues in the municipal agenda establishing its international relations secretariat and adhesion to the CCP (Biderman, 2011; Back, 2012 Macedo, 2017). Between 2004 and 2012, the PMSP intensified its environmental paradiplomatic activities. Its officials and staff participated as party delegates in several international conferences on sustainable development, including climate and biodiversity COPs. In 2005, São Paulo became a founding member of the original C40 large cities leadership group, and hosted its international conference in June 2011.

São Paulo was also the first city in the country to adopt a Municipal Climate Change Policy (Law 14.933/09) establishing mandatory GHG emission reduction targets, even before Brazil presented its voluntary targets in 2009, during COP15. It determines a reduction target of 30 percent of CO2e aggregate municipal emissions by 2012 relative to baseline year 2003. This target, however, proved too ambitious: the revised inventory showed that GHG emissions had increased by 8.7 percent in 2011 (Instituto Ekos Brasil et al., 2013) (Fig. 6).

São Paulo′s GHG emissions 2003–2011(GgCO2e). This figure is not covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Source: Instituto Ekos Brasil et al. (2013)

This result raised strong criticism from political adversaries, who opposed some of the proposed measures that challenged status quo and vested interests. Nevertheless, until 2012, the PMSP reported implementing many measures determined by the PMMC, resulting in positive change and improved urban sustainability. According to a decision-maker and leader at the time, arguing against the ineffectiveness of the law

“[…] levels of GHG in the city remained fairly stable despite huge growth in car ownership, thanks to investments in electrification and cleaner fuel for the public bus fleet […] converting two landfills to capture methane and generate energy reduced 10 percent of the city´s emissions.”Footnote 32

Despite providing the framework and encouraging climate action, the Climate Law was not effective in the short-term (Setzer et al., 2015). However, it fulfilled several of its objectives at the time.

The PMMC´s governance structure included an intense consultation process for the Bill of Law which was approved unanimously at City Council. It also established the Climate Change Committee (CMCEE), a consultative body with representatives from public and private sectors. The Law consolidated other policies by framing them as climate issues and several of its concerns were included in the city´s strategic master plan (PDE), revised in 2014Footnote 33 (Back, 2016; Di Giulio, 2017). Even if compliance remains a challenge, the framework is in place and will be able to support further experimentation (Caprotti and Cowley, 2016).

Many other benefits were reported by the administration in 2012, such as improved public transport and reduced air pollution. The GHG inventory was regarded as a key instrument to implement climate action; the PMMC determines its update biannually, but the third inventory, due in 2014, was not delivered. At the time of writing this article, the city´s environment department (SVMA) reported it was developing the inventory in-house, to be issued in 2019.

Discussions

ANAMMA´s survey provides evidence of increased urban climate action throughout the country from April 2017 to March 2018. Awareness and engagement at local level almost doubled in one year, rising from 4 to 7 percent of Brazilian municipalities. These developments can be directly linked to cities´ paradiplomatic activities (Toly, 2008; Setzer, 2009, Macedo, 2017). Moreover, the engagement of cities occurred regardless of their scale and geopolitical importance as demonstrated in Table 2. In relative terms, the most substantial increase in climate action has taken place in municipalities with less than 100,000 inhabitants, those considered small/medium according to official demographic criteria (IBGE, 2016, 2017) showed the most significant figures. In one year, climate change related activities doubled from 8 to 16 percent of the total in these citiesFootnote 34, demonstrating in-width development of urban experimentation.

Capital cities have taken the lead in climate paradiplomacy, mitigation measures, and urban governance experimentation since 2003. A correlation between these initiatives and participation in TMNs is noted after 2005. In June 2012, inspired by the C40, municipal environmental leaders established the CB27. So far, their activities are mainly political, and aim to foster information sharing and peer-to-peer learning, configuring governance experimentation beyond socio-technical interventions (Acuto and Rayner, 2016; Heijden, 2018). As regional hubs, these cities have a strong role in disseminating urban climate experiments and sustainability practices. Collaboration between TMNs and CB27 increased adhesion of Brazilian municipalities to collective pledges such as the GCMCE. However, as Abbott suggests, such voluntary commitments are limited, as they “[…] apply only modest criteria and vetting procedures, provide commitment-makers with limited support, and have few means to hold them accountable.” (2016, p. 3).

As demonstrated by the Belo Horizonte and São Paulo cases, policy implementation is still in its early stages, and GHG emissions inventories so far do not provide evidence of their effectiveness in terms of GHG reductions. However, measuring urban climate experimentation success based solely on these emission reductions would be misleading and unfair. Other factors must be weighed in, if the city´s performance is to be evaluated in a wider framework that examines climate and sustainability governance experiments (Jordan and Huitema, 2014; Kivimaa et al., 2017Footnote 35).

Implementing mandatory climate measures has been challenged by lack of political will and discontinuity, key factors in determining the success of experimentation (Bulkeley and Betsill, 2003). Nonetheless, as governance experiments, even in failing they provided valuable insights (Matschoss and Repo, 2018), such as the need for scenario studies before establishing reduction targets, an enforcement framework and public support.

Conclusion

Brazilian cities are progressively engaging in experimentation and strengthening the legal and institutional framework for multilevel climate governance (Heidjen, 2018). Whether these policies will result in reducing GHG emissions cannot be verified yet, since the timeframe is still short-term, and the data are insufficient. However, expanding experiments that challenge carbon-lock-in policies is crucial to sustainability transitions (Kivimaa et al., 2017). A movement is underway and might be a key factor in decision-making at federal level in the new administration, regarding Brazil´s pledge within the Paris Agreement. At the time of writing this paper, the newly elected presidency leans towards disregarding the climate change agenda, mainly due to historical conflicts between agribusiness and land tenure (OC, 2018). We may speculate that by reinforcing the economic, health and social benefits of urban climate action through experimentation, shifting the focus from AFOLU sectors, and creating political pressure at subnational levels might demonstrate the relevance of remaining in the Paris treaty.

Experiments have been successful in promoting peer-to-peer learning and reached beyond geographical boundaries and jurisdictions by affecting policies at state and national levels (Setzer, 2009, Biderman, 2011; Back, 2012; Macedo, 2017). However, to help cities go beyond collective pledges and improve learning from “informal” experimentation (Abbot, 2016; Heijden, 2018), the CB27 should tap into its capabilities as orchestrator to support a more structured approach based on science to analyse and understand these urban climate actions as experiments.

TMNs have helped support the global climate regime by integrating subnational governments from countries outside the international treaties or with limited commitments in voluntary climate mitigation (Andonova et al., 2009: 58; p. 67–68). Moreover, while TMNs helped internalise global climate goals in the municipal agenda in Brazil, cities engaged in climate experimentation within their capabilities and mandates, thus strengthening collective agency. Despite voluntary commitment limitations, such as lack of enforcement mechanisms to warrant compliance, the narrative is established at a local level and will contribute towards creating critical mass, and to put pressure on the federal government (CNM, 2008; Kivimaa et al., 2017).

This investigation further confirms that climate governance in Brazil requires improving institutional channels and consolidating dialogue across jurisdictions to implement strategies toward achieving mitigation goals. TNMs in coordination with national municipal associations, such as ANAMMA and the CB27 have the potential to facilitate a more inclusive policy approach leveraged by urban experiments. Engaging municipalities, conducting ex-post evaluations of these interventions with a more scientific approach, and improving the institutional framework for multilevel climate governance in Brazil will demonstrate that climate action and GHG emission reductions in the urban context will contribute toward reaching global goals beyond 2020.

Data availability

Some of the datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the form of a searchable database. Specific datasets cited, generated and/or analysed are publicly available as part of open and/or government sources. Others are included in the lead author's doctoral thesis available at: http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/106/106132/tde-18102017-203603/pt-br.php and cited wherever appropriate. Those that are not publicly available are either part of the authors' ongoing research or of ANAMMA's survey; further information can be obtained from the corresponding author, and by permission from ANAMMA upon reasonable request. Publicly accessible data in government websites: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística IBGE): https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/; Belo Horizonte´s Municipal Committee on Climate Change and Eco-efficiency, Environment Secretariat (Comitê Municipal de Mudanças Climáticas e Eco-eficiência, Secretaria de Meio Ambiente, Prefeitura de Belo Horizonte – CMMCEE/PBH): https://prefeitura.pbh.gov.br/meio-ambiente/comite-de-mudancas-climaticas. Belo Horizonte´s first GHG inventory: http://www.pbh.gov.br/smpl/PUB_P015/Relat%C3%B3rio+Final+Gases+Estufa.pdf. São Paulo´s Municipal Environment Secretariat (Prefeitura Municipal de São Paulo, Secretaria do Verde e do Meio Ambiente – SVMA-PMSP). The publications webpage of the climate change and eco-economy committee (Comitê de Mudanças Climáticas e Ecoeconomia-CMCE): https://www.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/cidade/secretarias/meio_ambiente/comite_do_clima/publicacoes/index.php?p=26184.

Notes

Global GHG emissions have continued to grow, but at a slower pace. Global levels of CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and industry over the past two to three years seem to be stabilising (UNEP, 2017).

Non-state actors’ zone on climate action (NAZCA), established during COP14 in Lima, Peru, and supported by TMNs.

Available at http://climateaction.unfccc.int/. Accessed on 19 June 2018

There are 38 registered Brazilian cities, of which 15 are state capital cities representing over 35 million inhabitants, including two global megacities: Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.

Findings presented here result from the main author´s research for a PhD, which began in 2013 and was publicly defended in October 2017. In the project, under supervision of Prof. Jacobi, the author studied the participation of Brazilian cities in multilevel climate governance, the role of TMNs and interactions between municipalities and the federal government. The research also consisted of several direct observations of local government participation in COP side events, the main author´s own professional experience (2003–2012) and interviews with 31 elite stakeholders (see Macedo, 2017). The authors updated information from the ongoing survey on local climate action up until March 2018.

A forum of environmental municipal secretaries from 26 Brazilian state capitals and the federal district of Brasília, launched during Rio + 20, in June 2012

This number corresponds to all motor vehicles, including lorries, buses, cars, motorcycles, etc. In Dec. 2017, the national fleet was 65.8 million vehicles. Figures provided by the national transport department DENATRAN available at http://www.denatran.gov.br/estatistica/237-frota-veiculos.

Merged with the Global Covenant of Mayors on Climate and Energy in 2016 (GCMCE, 2016)

Fifteenth session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP15/UNFCCC)

The PNMC establishes an avoidance target ranging between 36.1 and 38.9 percent by 2020 of projected emissions in a BaU scenario relative to 2005 as the baseline year. In absolute values, total emissions should be limited to 2068 Tg CO2eq in 2020. In 2015, LULUCF emissions dropped 53 percent relative to 2005.

Both beef and timber are mostly consumed domestically: Only 13% of beef produced in Brazil was exported in 2016 and the Southeast region accounts for the consumption of 80% of timber extracted in the Amazon region.

The PNMU determines that cities with a population over 20,000 inhabitants develop their municipal mobility plan by 2015; those that do not comply loose access to federal funds. A survey conducted with 3.342 municipalities (60% of the total) by the Ministry of Cities in 2015 and 2016 found that less than 10% of the qualifying cities had completed their municipal mobility plan, due mostly to lack of technical capacity and financial resources.

Along with projected investments in the oil sector, the Rota 2030 policy issued in July 2018 further incentivises auto manufacturers. For instance, they will be able to abate at least 10.2 percent of the value invested in R&D from taxes and have extended periods to pay back loans. On a positive note, the policy includes further benefits for investments in low-emission vehicles, such as hybrid and electric. https://economia.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,governo-lanca-rota-2030-com-abatimento-10-2-de-impostos-para-montadoras,70002389497

Personal communication, 2017

Rio also hosted ICLEI´s Latin America and the Caribbean Secretariat (LACS) between 2001 and 2006.

CCP South America website archives. http://archive.iclei.org/index.php?id=1759

In alphabetical order, not ranking.

Access to the results is restricted, and will be released when the survey is concluded. ANAMMA authorised special access for this research. The questionnaire is available only to members at http://www.anamma.org.br/single-post/2016/12/14/Munic%C3%ADpios-s%C3%A3o-convidados-a-participar-de-censo.

Ranging from public awareness raising campaigns, elaboration of a GHG emissions inventory; to fostering innovation, research and transition towards a low carbon economy. Most identified sustainable management of solid waste and improving urban mobility; several small and medium size cities mentioned addressing fire prevention and reducing deforestation, and sustainable agricultural practices.

Corresponding to the sum of valid responses, after a review of 1013 entries, some of which repeated or incomplete.

In 2016 there were 4905 municipalities in Brazil with up to 50,000 inhabitants (88% of the total); 148 with more than 200,000 inhabitants, of which 17 with over 1 million (IBGE, 2017)

Climate Summit for Local Leaders on 4 December 2015 at Paris City Hall; Cities and Regions Pavilion – TAP2015 from 1-11 December 2015.Report available at http://e-lib.iclei.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/COP21-Report-web.pdf

There were 433 respondents by April 2017, of which 45 percent had declared undertaking at least one climate intervention in their municipalities. In March 2018, there was a 74 percent increase in overall responses, and reported climate action grew by 63 percent. When considering the total 5570 Brazilian municipalities (IBGE, 2016), 4 percent had engaged in climate action until early 2017; a year later, there were 7 percent.

There are 26 states and one federal district

Information available at: http://www.kas.de/brasilien/pt/publications/31346/.

Trailblazer cities such as Belo Horizonte, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo already had GHG inventories and climate regulations in place before 2014.

In June 2016, the main transnational coalitions on climate municipal leadership, the Covenant of Mayors and the Compact of Mayors, merged to form The Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy (GCMCE), gathering over 7400 cities. Available at https://www.globalcovenantofmayors.org/

Personal communication, 2017

Personal communication, 2017

Information provided by the CMMCE coordinator and available at http://portalpbh.pbh.gov.br

Information on São Paulo´s climate action and paradiplomacy was obtained in the city´s website and official documents, as well as in TNMs reports on their members´ activities.

Personal communication, 2017

Municipal law determines that the city´s strategic master plan (Plano Diretor Estratégico–PDE) be revised every 10 years. The previous one was in force since 2002.

Regarding the sample, in 2017, there were 52 responses, whereas in 2018, the number increased to 100 cities. Twenty-nine respondents declared having engaged in climate action in 2017, by 2018 there were 57 such responses.

To contribute to the understanding of diversity in experimenting, Kivimaa et al., (2017) undertook a systematic review of articles published between 2009 and 2015, and suggest a typology of climate governance experiments, based on their reported outcomes. The survey of 18 peer-reviewed articles reporting on 29 governance experiments identifies four types of governance experiments: niche creation, market creation, spatial development, and societal problem solving and change.

References

Abbott KW (2012) The transnational regime complex for climate change. Environ Plan C 30(4):571–590

Abbot KW (2016) Orchestrating experimentation in non-state environmental commitments. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2851650 Accessed 12 Sep 2016

Abbott K, Genschel P, Snidal D, Zangl B (2015) International organizations as orchestrators. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Acuto M, Rayner S (2016) City networks: breaking gridlocks or forging (new) lock-ins? Int Aff 92(5):1147–1166

Acuto M, Parnell S, Seto K (2018) Building a global urban science. Nat Sustain 1:2–4

Almeida LA, Silva MAR, Pessoa RAC (2013) Participação em redes transnacionais e a formulação de políticas locais em mudanças climáticas: o caso de Palmas. Rev Adm Pública 47(6):1429–1449

Andonova L, Betsill M, Bulkeley H (2009) Transnational climate governance. Glob Environ Polit 9:52–73. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2009.9.2.52.

Andonova L, Hale T, Roger C (2014) How Do Domestic Politics Condition Participation in Transnational Climate Governance? Working Paper. Political Economy of International Organizations conference Princeton, January 16–18, 2014 http://wp.peio.me/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Conf7_Andonova-Hale-Roger-31.08.2013.pdf

Aprigio A (2016) Paradiplomacia e interdependência: as cidades como atores internacionais. Gramma, Rio de Janeiro

ASSOCIAÇÃO NACIONAL DE ÓRGÃOS MUNICIPAIS DE MEIO AMBIENTE–ANAMMA (2018) Censo Ambiental. ANAMMA http://www.anamma.org.br/single-post/2016/12/14/Munic%C3%ADpios-s%C3%A3o-convidados-a-participar-de-censo. Accessed 23 March 2018

Back AG (2012) Agenda climática do município de São Paulo: contribuição de redes transnacionais de governos locais. Teor Pesqui 2(2):97–107

Back AG (2016) Urbanização, Planejamento e Mudanças Climáticas: desafios da Capital Paulista e da Região Metropolitana de São Paulo. Thesis, Universidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCAR), São Carlos. 240 pp

Bäckstrand K, Kuyper J, Linnér W, Lövbrand E (2017) Non-state actors in global climate governance: from Copenhagen to Paris and beyond. Environ Polit 26(4):561–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2017.1327485

Bansard JS, Pattberg PH, Widerberg O (2017) Cities to the rescue? Assessing the performance of transnational municipal networks in global climate governance. Int Environ Agreem 17(2):229–246

Barbi F (2014) Governando as Mudanças Climáticas no Nível Local: Riscos e Respostas Políticas. (PhD) Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas

Bernstein S, Hoffmann M (2018) The politics of decarbonization and the catalytic impact of subnational climate experiments. M Policy Sci 51:189. 2018

Betsill M, Bulkeley H (2004) Transnational networks and global environmental governance: the cities for climate protection program. Int Stud Q 48:471–493

Betsill M, Bulkeley H (2006) Cities and the multilevel governance of global climate change. Glob Gov 12(No. 2):141–159

Betsill M, Bulkeley H (2007) Looking back and thinking ahead: a decade of cities and climate change research. Local Environ 12(5):447–456

Biderman R (2011) Limites e alcances da participação pública na implementação de políticas subnacionais em mudanças climáticas no município de São Paulo. (PhD), Fundação Getúlio Vargas, São Paulo

Biermann F, Pattberg P (2012) Global environmental governance reconsidered. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Bouteligier S (2014) A networked urban world–empowering cities to tackle environmental challenges. In: Curtis Simon(ed) The power of cities in international relations. Routledge, London, p 71–87

BRAZIL (2015) Pretendida Contribuição Nacionalmente Determinada e informação adicional sobre a iNDC apenas para fins de esclarecimento. Ministério de Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovações e Comunicações (MCTIC), Brasília, DF, http://www.itamaraty.gov.br/images/ed_desenvsust/BRASIL-iNDC-portugues.pdf

BRAZIL (2017) Second Biennial Update Report of Brazil to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Ministério de Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovações e Comunicações (MCTIC), Brasília, DF, http://sirene.mcti.gov.br/documents/1686653/2091005/BUR2-PORT-02032017_final.pdf/91e855c5-0e73-41e0-9df2-1fc0b723a51d

Brazil and Observatório das Metrópoles (OM), Rodrigues J (2015) Estado da motorização individual no Brasil - Relatório 2015. INCT/UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro, http://www.observatoriodasmetropoles.net/download/automoveis_e_motos2015.pdf

Brun A (2016) Conference diplomacy: the making of the Paris agreement. In Hovi J, Skodvin T (eds) Politics and Governance, Vol. 4, Issue 3 Lisbon: Cogitatio Press. pp. 115–123. www.cogitatiopress.com/politicsandgovernance

Bulkeley H, Betsill M (2005) Rethinking sustainable cities: multilevel governance and the ‘urban’ politics of climate change. Environ Polit 14(1):42–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964401042000310178

Bulkeley H, Castán-Broto V (2013) Government by experiment? Global cities and the governing of climate change. Trans Inst Br Geogr 38(3):361–375

Bulkeley H, Hoffmann MJ, Vandeveer S, Milledge V (2012) Transnational governance experiments. In: Biermann F, Pattberg P (eds) Global environmental governance reconsidered. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Caprotti F, Cowley R (2016) Interrogating urban experiments. Urban Geogr 38(9):1441–1450. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1265870

Castán-Broto V, Bulkeley H (2013) A survey of urban climate change experiments in 100 cities. Glob Environ Change 23(1):92–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.07.005

CB27/KAS (2017) Carta de Brasília pela Sustentabilidade http://sams.iclei.org/fileadmin/user_upload/SAMS/CB27/Carta_de_Brasi__lia_pela_Sustentabilidade_VF.pdf

Cerqueira BLA, Vicente MCP (2016) Desafio do enfrentamento às mudanças climáticas nas capitais brasileiras. In: KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG–KAS. Mudanças Climáticas: o desafio do século. Fundação Konrad Adenauer, Rio de Janeiro

CONFEDERAÇÃO NACIONAL DOS MUNICÍPIOS – CNM (2008) Atuação Internacional Municipal: Estratégias para Gestores Municipais Projetarem Mundialmente sua Cidade. Colet Gest Pública Munic 13:120

Corfee-Morlot J, Kamal-Chaoui L, Donovan MG, Cochran I, Robert A, Teasdale P (2009). Cities, Climate Change and Multilevel Governance. OECD Environmental Working Papers N° 14, 2009, OECD publishing, ©OECD. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/governance/regional-policy/44232263.pdf Accessed 1 Jan 2017

Di Giulio GM, Bedran-Martins AM, Vasconcellos MP, Ribeiro WC (2017) Mudanças climáticas, riscos e adaptação na megacidade de São Paulo, Brasil. Sustentabilidade em Debate-Brasília, vol. 8, n.2, p. 75-87, ago/2017

Dingwerth K, Pattberg P (2006) Global governance as a perspective on world politics Glob Gov 12(2):185–203 http://www.jstor.org/stable/27800609

Duchacek ID (1984) The international dimension of subnational self-government. Publius 14(4):5–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/3330188

Farias VC (2015) Regime Internacional de Mudanças Climáticas: Paradiplomacia Ambiental do Estado de São Paulo (PhD). Universidade de Santos, Santos

Fischer K et al. (2015) Urbanization and climate diplomacy: the stake of cities in global climate governance. climate diplomacy series. Adelphi, Berlin

Frug G (2011) Democracy and governance. In: Burdett R, Sudjic D(eds) Living in the endless city. Phaidon Press, London

Global Protocol for Community-Scale Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventories–GPC (2014) World Resources Institute. http://ghgprotocol.org/files/ghgp/GHGP_GPC.pdf

Gordon D, Acuto M (2015) If cities are the solution, what are the problems? The promise and perils of urban climate leadership. In:Johnson C, et al. (eds) The urban climate challenge: rethinking the role of cities in the global climate regime. Routledge, London

Granziera ML, Rei FC (2015) O Futuro do Regime Internacional das Mudanças Climáticas: aspectos Jurídicos e Institucionais. SBDIMA, Santos

Heijden JVD (2018) City and subnational governance-high ambitions, innovative instruments and polycentric collaborations? In: Jordan A, Huitema D, Asselt HV, Forester J (eds) Governing climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hickmann T (2016) Rethinking authority in global climate governance: how transnational climate initiatives relate to the international climate regime. Routledge, London

Hickmann T, Fuhr H, Höhne C, Lederer M, Stehle F (2017) Carbon governance arrangements and the nation‐state: the reconfiguration of public authority in developing countries. Public Adm Dev 37(5):331–343. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1814

Inoue C (2016) Governança global do clima: proposta de um marco analítico em construção. Rev Carta Inter Belo Horizonte 11(1):91–117. https://doi.org/10.21530/ci.v11n1.2016.242

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE (2017). Estimativas 2017 Municípios. https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas-novoportal/sociais/populacao/9103-estimativas-de-populacao.html?edicao=16985&t=resultados

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística-IBGE (2016). Estimativas da população residente no Brasil e Unidades da Federação com Data de Referência em 1o de julho de 2016. https://ww2.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/estimativa2016/estimativa_dou.shtm

Instituto Ekos Brasil, Geoklock Consultoria e Engenharia Ambiental and Prefeitura Municipal de São Paulo-PMSP (2013) Inventário de emissões e remoções antrópicas de gases de efeito estufa do Município de São Paulo de 2003 a 2009 com atualização para 2010 e 2011 nos setores Energia e Resíduos. São Paulo: ANTP. https://issuu.com/svmasp/docs/caderno_t__cnico_invent__rio_gee

Johnson C, Toly N, Schroeder H (eds) (2015) The urban climate challenge: rethinking the role of cities in the global climate regime. Routledge, New York

Jordan A, Huitema D (2014) Innovations in climate policy: the politics of invention, diffusion, and evaluation. Environ Polit 23(5):715–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2014.923614

Keohane R, Victor D (2009) The Regime Complex for Climate Change. Harvard Project on International Climate Agreements, Cambridge. http://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy/files/KeohaneVictor_Final.pdf

Keohane R, Oppenheimer M (2016) Paris: beyond the climate dead end through pledge and review? In:Hovi J, Skodvin T (eds) Politics and governance. p. 142–151

Kern K, Alber G (2009) Governing climate change in cities: modes of urban climate governance in multi-level systems. http://search.oecd.org/governance/regional-policy/50594939.pdf#page=172

Kivimaa P, Hild M, Huitema D, Jordan A, Newig J (2017) Experiments in climate governance: a systematic review of research on energy and built environment transitions J Clean Prod 169:17–29 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652617300343?via%3Dihub

Knirsch T (ed) (2012) Environmental management: success cases of the Brazilian state capitals. Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, Rio de Janeiro, p 64

Koehntopp P (2010) Governança climática nas cidades contemporâneas: Caso de Joinville, SC. (PhD). Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis

La Rovere E, Macedo LV, Baumert K (2002) The Brazilian proposal on relative responsibility for global warming. In: Baumert K, Blanchard O, Llosa S, Perkaus J (eds) Building on the Kyoto protocol: assessing options for protecting the climate system. WRI, Washington

IES-Brasil, Fórum Brasileiro de Mudanças Climáticas-FBMC (2016) Implicações econômicas e sociais dos cenários de mitigação de GEE até 2030. Sumário técnico. FBMC/COPPE-UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro. http://www.centroclima.coppe.ufrj.br/images/Noticias/documentos/ies-brasil-2030/2_sumario-executivoingles.pdf

Macedo LSV (2017) Participação das Cidades Brasileiras na Governança Multinível das Mudanças Climáticas. PhD Thesis. Universidade de São Paulo-USP. São Paulo. http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/106/106132/tde-18102017-203603/pt-br.php

Macedo LV, Setzer J, Rei FC (2016) Transnational Action Fostering Climate Protection in the City of São Paulo and Beyond. disP. Planning Rev 52(2):35–44

Marcovitch J, Dallari P (2014) Relações Internacionais de Âmbito Subnacional: A Experiência de Estados e Municípios no Brasil. Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo

Matschoss K, Repo P (2018) Governance experiments in climate action–empirical findings from the 28 European Union countries. Environ Polit https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1443743

Mauad AC, Viola E, Schmitz GO, Rocha RA (2017) Governança Global do Clima: do regime internacional multilateral à nova complexidade – potências climáticas, coalizões plurilaterais, alianças de atores não estatais e complexos sociotécnicos descarbonizantes. Brasil e o Sistema das Nações Unidas: desafios e oportunidades na governança global. Ipea, Brasília, p 399–422

Mauad CE, Matsumoto CEH, Cezário GL (2013) Internacionalização a partir do Local–um enfoque sobre os Governos municipais brasileiros. http://www.gustavocezario.com.br/gustavocezario/Publicacoes_files/Internacionalizac%CC%A7a%CC%83o%20a%20partir%20do%20local.pdf

Morrison TH, Adger WN, Brown K, Lemos MC, Huitema D, Hughes TP (2017) Mitigation and adaptation in polycentric systems: sources of power in the pursuit of collective goals. WIREs Clim Change 8:e 479. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.479. 2017

Observatório do Clima-OC (2017) Análise da evolução das emissões de GEE no Brasil (1990-2015). OC, São Paulo, http://seeg.eco.br/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/RelatoriosSeeg2017-Sintese_final.pdf

Observatório do Clima-OC (2018) São Paulo: OC. Platform for data on GHG emissions in Brazil per sector. http://plataforma.seeg.eco.br/total_emission

Ostrom E (2009) A Polycentric approach for coping with Climate Change. Policy Research Working Papers. The World Bank. http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/1813-9450-5095

PAINEL BRASILEIRO DE MUDANÇAS CLIMÁTICAS-PBMC (2014) Mitigação das mudanças climáticas. In: Bustamante M, La Rovere E (eds) Contribuição do Grupo de Trabalho 3 do Painel Brasileiro de Mudanças Climáticas ao Primeiro Relatório da Avaliação Nacional sobre Mudanças Climáticas. COPPE/UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro

Piattoni S (2010) The theory of multi-level governance: conceptual, empirical and normative challenges. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Pluijn RVD (2007) City diplomacy: the expanding role of cities in international politics. https://www.uclg.org/sites/default/files/20070400_cdsp_paper_pluijm.pdf

Prefeitura de Belo Horizonte–PBH (2015) 3° Inventário de emissão de gases de efeito estufa: Atualização 2011/2012/2013. Período de Referência: 2000 a 2013. Relatório Técnico Final. PBH, Belo Horizonte, file:///C:/Users/Dell/Documents/001_PRINCIPAL_2017/08_BIBLIOTECA/3o_Inventario_Emissoes_GEE_2015%20(1).pdf

Prefeitura de Belo Horizonte–PBH (2016a) Plano Estratégico BH. https://bhmetaseresultados.pbh.gov.br/content/planejamento-estrat%C3%A9gico-2030

Prefeitura de Belo Horizonte–PBH (2016b) Análise de Vulnerabilidade às Mudanças Climáticas/ Vulnerability Assessment to Climate Change in the Municipality of Belo Horizonte. PBH, Belo Horizonte, file:///C:/Users/Dell/Documents/001_PRINCIPAL_2017/08_BIBLIOTECA/relat_vulnerabilidade_bh.pdf

Puppim de Oliveira JA (2009) The implementation of climate change related policies at subnational level: an analysis of three countries. Habitat Int 33(3):253–259

Puppim de Oliveira JA, Doll CNH, Kurniawan TA, Geng Y, Kapshe M, Huisingh D (2013) Promoting win–win situations in climate change mitigation, local environmental quality and development in Asian cities through co-benefits. J Clean Prod 58:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.08.011. 2013ISSN 0959-6526